Geographic Mobility in Pediatric and Geriatric Populations: Implications for Clinical Research and Drug Development

This article examines the distinct drivers of high geographic mobility in pediatric and older adult populations and their critical implications for biomedical research.

Geographic Mobility in Pediatric and Geriatric Populations: Implications for Clinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article examines the distinct drivers of high geographic mobility in pediatric and older adult populations and their critical implications for biomedical research. For older adults, mobility is primarily driven by health declines, such as cardiovascular events, and the need for informal caregiving, often resulting in relocations closer to adult children. For children, mobility is often linked to parental life course events. These patterns present significant methodological challenges for longitudinal studies, clinical trial retention, and pharmacovigilance systems, which can be addressed through targeted recruitment, dynamic follow-up protocols, and digital health technologies. A comparative analysis of mobility triggers and their impact on healthcare engagement reveals the necessity for tailored, life-course-informed research strategies to ensure representative sampling and data integrity in drug development.

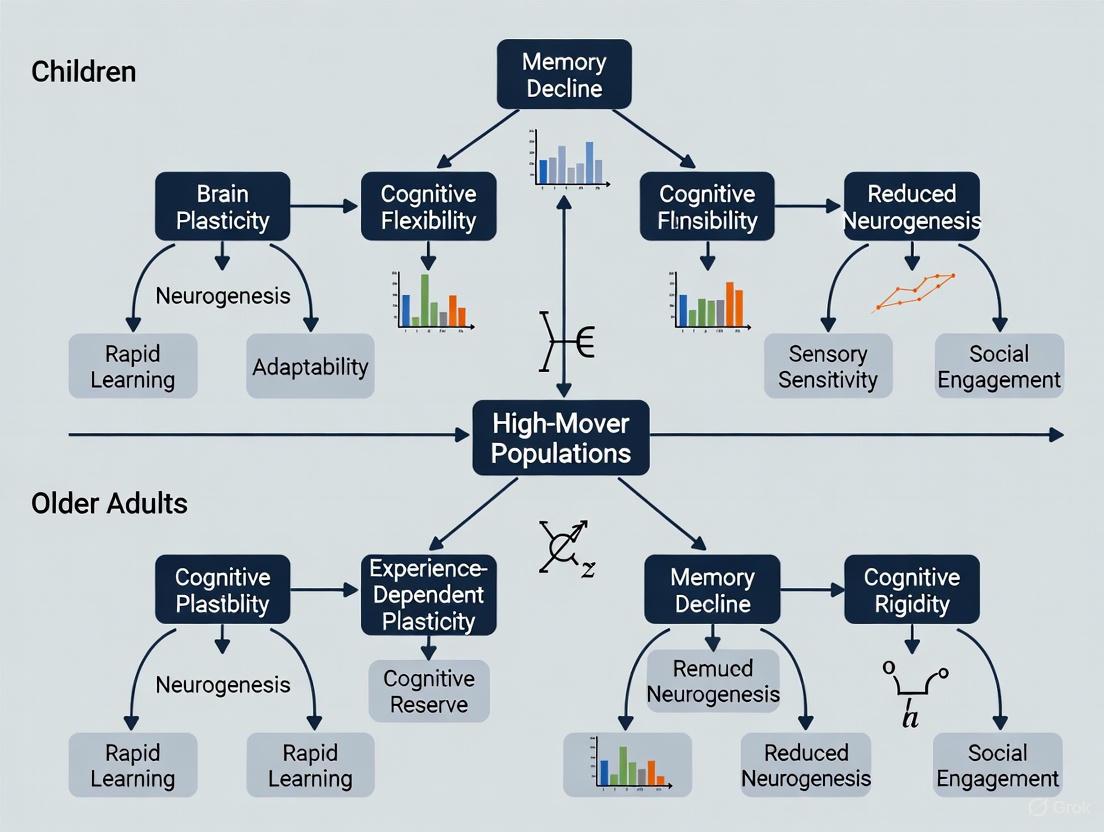

Understanding the Core Drivers of Mobility in Vulnerable Populations

Late-life mobility, a critical area of gerontological research, is predominantly driven by health triggers and the ensuing need for care. This whitepaper synthesizes quantitative evidence from longitudinal cohort and population register studies to delineate the specific health events that precipitate residential moves among older adults. Framed within the broader context of life-course mobility, where both young adults and older individuals constitute high-mover populations, this analysis details the experimental methodologies used to establish causality and pattern. The findings underscore that health-driven mobility is a strategic adaptation to disability, fundamentally shaping intergenerational living arrangements and care networks.

Population aging necessitates a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind late-life mobility. While young adults move primarily for education, employment, and family formation [1], older adults experience a distinct mobility resurgence driven by different triggers. The life course exhibits a pronounced peak in residential mobility in early adulthood (ages 20-30), a period of stabilization, and then a second, significant phase of mobility in later life linked to health transitions [2]. This paper positions late-life mobility not as a random event, but as a strategic adaptation to changing capacities and care needs, a process that can be rigorously quantified and modeled.

Understanding these patterns is vital for multiple stakeholders. For researchers, it clarifies confounding factors in longitudinal studies where residential mobility can introduce selection bias or exposure misclassification [3] [4]. For drug development and health services professionals, it highlights critical periods of intervention and the need for therapies that can delay disability and thus alter the trajectory of care needs and subsequent relocation.

Quantitative Evidence: Health Events as Predictors of Residential Moves

Robust, longitudinal data from multiple large-scale studies consistently demonstrates a strong association between specific health triggers and increased mobility in older populations. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Health Triggers and Associated Mobility Outcomes in Older Adults

| Health Trigger | Population Studied | Mobility Outcome | Measured Effect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Health Problems (Parents ≥80 years) | Swedish Population Registers | Parent moves closer to child | Increased likelihood | [1] |

| Severe Health Problems (Parents ≥80 years) | Swedish Population Registers | Parent moves to institution | Increased likelihood | [1] |

| First Cardiovascular Event (Stroke, Heart Attack, CHF) | U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Child moves closer to parent | 1.55x increased probability (Relative Risk Ratio) | [5] |

| First Cardiovascular Event (Stroke, Heart Attack, CHF) | U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Parent and child move in together | 1.61x increased probability (Relative Risk Ratio) | [5] |

| Self-Rated Poor Health | Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort | Short-distance move | Significant positive association | [3] [4] |

| Physical Limitations | Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort | Short-distance move | Significant positive association | [3] [4] |

Table 2: Moderating Factors in Health-Triggered Mobility

| Moderating Factor | Effect on Mobility Probability | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Child's Gender | Older mothers are more likely to move closer to a daughter than a son [1]. | Intergenerational moves |

| Parent's Marital Status | The effect of a cardiovascular event is stronger for spouseless older parents [5]. | Moves following a health crisis |

| Location of Other Children | Children are more likely to move closer to a parent if a sibling already lives nearby [1]. | Moves following a health crisis |

| Move Distance | Poor health and physical limitations are more strongly associated with short-distance moves than long-distance moves [3] [4]. | General late-life mobility |

Methodological Protocols: Establishing Causal Inference

Establishing that health triggers cause mobility, rather than merely correlate with it, requires sophisticated longitudinal study designs and statistical models. The following protocols are derived from the cited seminal research.

Protocol: Analyzing Intergenerational Moves in Response to Health Shocks

This protocol is based on the study of cardiovascular events using the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) [5].

- Objective: To determine if a discrete, severe health event causes changes in intergenerational residential proximity.

- Data Source: Longitudinal, nationally representative surveys (e.g., HRS) with biennial interviews. Must include modules on health history, residential addresses of respondents and their children, and family structure.

- Sample Selection:

- Restrict baseline sample to respondents living in the community, above a certain age (e.g., 55+), without a history of the specific health condition under study (e.g., CVD).

- Include only respondents with at least one non-coresident child at baseline to ensure the possibility of a proximity-enhancing move.

- Key Variables:

- Independent Variable: Incident health event (e.g., first-ever stroke, heart attack, or congestive heart failure), confirmed in a follow-up wave.

- Dependent Variable: Change in residential proximity between baseline and follow-up, categorized as: (a) child moves closer to parent, (b) parent and child move in together, (c) no change, (d) move further apart.

- Covariates: Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, income, baseline functional limitations, and number of children.

- Statistical Analysis: Multinomial logistic regression to model the likelihood of each proximity change category as a function of the health event, adjusting for covariates. Results are expressed as relative risk ratios.

Protocol: Predicting Movers vs. Non-Movers in an Aging Cohort

This protocol is based on analyses of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort [3] [4].

- Objective: To characterize movers and identify predictors of short- and long-distance moves in a middle-aged and early-retirement cohort.

- Data Source: Established longitudinal cohort (e.g., ARIC) with geocoded residential addresses at multiple visits and extensive covariate data.

- Move Identification:

- Geocode all participant addresses at sequential study visits.

- Calculate pairwise distances between consecutive addresses.

- Classify participants as: Non-movers, Short-distance movers (within county), or Long-distance movers (outside county).

- Predictor Variables: Collect data from six categories: sociodemographic characteristics, health and psychosocial factors, incident life "triggers" (e.g., retirement, widowhood), characteristics of the physical home, and neighborhood-level characteristics.

- Statistical Analysis: Use best-subset selection algorithms to identify the most important predictors of moving. Crucially, include interaction terms between predictors (e.g., age and health status) to improve model fit and uncover substantive relationships. Compare the characteristics of short-distance and long-distance movers to non-movers.

The logical workflow for investigating health-triggered mobility, from study design to analysis, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Essential Materials

For researchers investigating late-life mobility, the following "research reagents" are critical resources.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Research on Late-Life Mobility

| Research Resource | Type | Function & Application | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linked Population & Health Registers | Data Source | Provides complete, longitudinal data on an entire population for residential moves, health diagnoses, and family linkages, minimizing selection bias. | Swedish Administrative Registers [1] |

| Longitudinal Cohort Studies | Data Source | Provides deep, rich data on health, socioeconomic, and psychosocial variables linked to residential history over time. | Health and Retirement Study (HRS) [5], Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) [3] |

| Geocoded Address Histories | Data / Method | Enables precise, objective calculation of move distances and classification of move type (short vs. long distance). | ARIC study geocoding [3] |

| Multinomial Logistic Regression | Statistical Model | Models the likelihood of falling into one of multiple unordered mobility categories (e.g., move closer, move in, no change) based on health triggers. | HRS analysis of proximity changes [5] |

| Best-Subset Selection Algorithms | Statistical Method | Identifies the most important predictors of moving from a large set of variables, including meaningful interactions. | ARIC analysis of mover characteristics [4] |

The evidence is conclusive: health triggers and the associated care needs are a primary driver of mobility in later life. This movement is a non-random, strategic adaptation characterized by proximity-enhancing relocations to adult children, particularly daughters, and transitions to institutional care. The phenomenon is distinct from the mobility of younger populations in its triggers but similar in its role as a key life-course adaptation.

For the research and drug development community, these findings have profound implications:

- Clinical Trial Design: Recruitment and retention strategies must account for the high mobility of older populations following health events to prevent attrition bias.

- Endpoint Selection: Functional mobility and independence (ADLs/IADLs) are critical endpoints, as their decline is a direct precursor to life-altering relocations.

- Health Economics: The full cost of diseases like CVD and stroke must include the significant social and economic impacts of resultant residential moves and changes in caregiving. Future research should leverage emerging technologies and linked data to further elucidate the mechanisms linking specific disease pathways to mobility decisions, ultimately informing interventions that support healthy aging in place.

This whitepaper examines the dynamics of informal support networks, focusing on the migratory patterns of children and older adults as high-mover populations in response to health and familial crises. Within the context of a broader thesis on high-mobility populations, this analysis synthesizes quantitative data and qualitative research to elucidate the critical roles undertaken by daughters and siblings. The findings demonstrate that informal care structures significantly influence residential decisions, with quantitative models revealing increased relocation probabilities following cardiovascular events and qualitative studies highlighting the undervalued contributions of young siblings in psychiatric care contexts. This paper provides methodologies, data visualizations, and analytical frameworks to guide future research and inform policy decisions aimed at supporting these essential care networks.

The mobility patterns of children and older adults represent a critical area of demographic research, particularly concerning the formation and maintenance of informal support networks. Informal support networks, comprising family members who provide unpaid care and assistance, serve as a primary source of caregiving during health crises and developmental challenges [6] [5]. This paper frames its investigation within the broader thesis that children and older adults constitute high-mover populations due to their heightened dependency on these familial structures.

Among older adults, health declines—particularly unexpected cardiovascular events—act as powerful catalysts for residential relocation, either bringing adult children closer to parents or parents closer to children [5]. Conversely, among children, the presence of a sibling with significant health needs creates a unique caregiving dynamic that shapes family systems and developmental outcomes [6]. Within these networks, daughters disproportionately assume caregiving roles for aging parents, while siblings of children with psychiatric disorders often provide substantial emotional and practical support despite their own developmental needs [6] [5].

This whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical analysis of these phenomena, emphasizing quantitative methodologies, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to advance understanding of how informal support networks influence population mobility and health outcomes.

Quantitative Analysis of Support-Driven Mobility

Cardiovascular Events and Proximity Changes

Analysis of longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) reveals a significant association between the onset of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and changes in intergenerational residential proximity. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from a nationally representative study of older adults in the United States [5].

Table 1: Impact of First Cardiovascular Event on Residential Proximity to Adult Children

| Variable | Baseline Probability (No CVD) | Post-CVD Probability | Relative Risk Ratio | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Move In Together | 1.2% | 1.9% | 1.61 | p < 0.05 |

| Move Closer | 4.1% | 6.4% | 1.55 | p < 0.05 |

| Any Proximity Increase | 5.3% | 8.3% | 1.57 | p < 0.05 |

The data demonstrates that a first cardiovascular event increases the two-year predicted probability of children and parents moving closer together, with specific subgroups showing heightened responsiveness [5]:

- Spouseless older adults: Those without a spouse were significantly more likely to experience proximity changes with adult children following CVD onset, highlighting the substitution effect between spousal and child caregiving.

- Daughter availability: Families with at least one daughter showed greater responsiveness to CVD events, confirming the predominant role of daughters in providing informal care support.

- Stroke survivors: Compared to other cardiovascular conditions (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure), stroke—which often results in more severe long-term disability—triggered more substantial residential adjustments.

Sibling Impact and Emotional Adaptation

Qualitative research on siblings of children with psychiatric disorders reveals substantial impacts, though these effects often resist simple quantification. The following table synthesizes findings from hermeneutic phenomenological analysis of interviews with 13 siblings aged 8-15 [6].

Table 2: Impacts and Support Needs of Siblings of Children with Psychiatric Disorders

| Impact Domain | Manifestation | Support Need | Preferred Support Modality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Conflict | Guilt, resentment, ambivalence about family adaptation to sibling's needs | Personalized attention from parents; acknowledgment of personal struggles | Informal, conversational support rather than structured therapy |

| Social Functioning | Restricted social activities; concerns about explaining sibling's condition to peers | Peer connection with others in similar situations; normalization of experience | Play-based interactions; casual group settings |

| Family Dynamics | Perceived inequity in parental attention; responsibility for sibling care | Involvement in care process; age-appropriate information about sibling's condition | Family inclusion in treatment planning; shared activities |

| Identity Development | Defining self in relation to sibling's needs; increased maturity and empathy | Recognition of individual strengths and achievements outside caregiving role | Mentoring relationships; opportunities for personal achievement |

Methodological Approaches

Longitudinal Analysis of Residential Proximity

Study Design and Population: The investigation into cardiovascular events and proximity changes employed a longitudinal design using waves from the Health and Retirement Study (2004, 2006, 2008) [5]. The baseline sample included respondents who were: (1) aged 55+ in 2004; (2) living in the community; (3) interviewed in 2004 and 2006/2008; (4) without CVD history as of 2004; and (5) had no co-resident child but at least one non-coresident child in the prior interview.

Key Variables and Measurement:

- Cardiovascular events: Included new onset of stroke, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure between survey waves, identified through self-report.

- Residential proximity: Measured using geographic information on children's residences, categorized as: (1) same household; (2) <1 mile; (3) 1-10 miles; (4) 10-100 miles; (5) 100+ miles; (6) unknown.

- Covariates: Included age, gender, race, education, income, wealth, marital status, number of children, baseline health conditions, and functional limitations.

Analytical Approach: Multinomial logistic regression models estimated the association between incident CVD and changes in proximity, adjusting for covariates. Models specifically tested interaction effects for spouseless individuals and those with daughters.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology in Sibling Research

Qualitative Methodology: The investigation of siblings' experiences employed a hermeneutic phenomenological framework to interpret the meaning of lived experiences [6]. This approach recognizes that personal narratives provide access to how individuals evaluate life conditions and ascribe meaning to them.

Data Collection Protocol:

- Participant Recruitment: Purposive sampling of children (ages 8-16) with siblings diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, recruited through a child psychiatric day clinic.

- Interview Protocol: Unstructured interviews conducted in chosen locations to build trust, beginning with neutral questions before exploring sibling relationships. Sessions lasted ≤60 minutes.

- Ethical Considerations: Project approval by Medical Ethical Commission; written informed consent from participants and parents.

Analytical Process: The hermeneutic analysis proceeded through three distinct phases [6]:

- Naïve Reading: Initial reading of interview transcripts to develop preliminary understanding.

- Structural Analysis: Identification of recurring structures and coding of text into "meaning units." Comparison of individual "sub-themes" across interviews to identify shared "main themes."

- Validated Interpretation: Continuous validation of meaning units, subthemes, and main themes through circular refinement against previous analytical stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Resources for Support Network Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Nationally representative longitudinal dataset | Tracking residential proximity changes before/after health events | Biennial survey; demographic, economic, health data; geographic child locations |

| Hermeneutic Phenomenological Framework | Qualitative analysis of lived experiences | Interpreting meaning in siblings' narratives of family life | Three-phase approach: naïve reading, structural analysis, validated interpretation |

| Multinomial Logistic Regression | Statistical modeling of categorical outcomes | Predicting probability of proximity change categories post-CVD | Handles nominal dependent variables; estimates relative risk ratios |

| ACT Rules for Color Contrast | Ensuring visual accessibility in research dissemination | Creating compliant data visualizations and diagrams | Minimum 4.5:1 contrast ratio for normal text; 3:1 for large text [7] [8] [9] |

| Open DOT Language | Standardized graph visualization | Diagramming methodological workflows and conceptual models | Text-based graph description; compatible with Graphviz tools |

The investigation of informal support networks reveals consistent patterns in the mobility behaviors of children and older adults as high-mover populations. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that health shocks, particularly cardiovascular events, systematically trigger residential realignments within families, with daughters assuming disproportionate caregiving responsibilities. Qualitative findings illuminate the complex emotional landscapes of siblings providing support to brothers and sisters with psychiatric disorders, highlighting their need for acknowledgment and age-appropriate inclusion rather than formalized support structures.

These findings carry significant implications for researchers, healthcare professionals, and policy makers seeking to understand and support these critical care networks. Future research should continue to develop integrated methodologies that bridge quantitative and qualitative approaches, creating more comprehensive models of how informal support networks shape population mobility and wellbeing across the lifespan.

This technical guide examines pediatric and older adult populations as high-mobility groups within life course theory. While children experience mobility primarily through parental decisions shaped by educational opportunities, health considerations, and socioeconomic factors, older adults typically move in response to health declines and care needs. Analyzing data from longitudinal studies and population registers, this whitepaper identifies key drivers across life stages and demonstrates how early-life mobility patterns establish trajectories with long-term consequences for health, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status. The structural dynamics creating high mobility in these populations provide critical insights for researchers and policy professionals addressing intergenerational health and social stratification.

Life course perspective provides the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding why children and older adults constitute high-mobility populations. This approach conceptualizes human development as a lifelong process shaped by historical and social contexts, with earlier life events establishing trajectories that influence subsequent outcomes [10]. Within this framework, mobility represents not merely geographical relocation but a manifestation of broader social and biological processes that unfold across distinct developmental periods.

The life course principle of timing recognizes that the impact of transitions and events depends on when they occur in a person's life. For children, mobility decisions are predominantly made by parents and reflect complex calculations balancing perceived opportunities against constraints. These decisions often cluster around key transition points in educational systems, creating predictable mobility patterns around school entry ages [10]. In contrast, older adult mobility frequently responds to health triggers such as new limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), widowhood, or the need for specialized care [11] [12].

Both populations experience decreased autonomy in mobility decisions compared to working-age adults—children due to developmental dependence, and older adults due to health-related dependencies. This shared structural position as dependent populations creates parallel methodological challenges for researchers studying mobility patterns and their consequences.

Pediatric Mobility: Parental Decisions and Educational Trajectories

Quantitative Patterns in Pediatric Mobility Drivers

Table 1: Primary Drivers of Pediatric Mobility Based on Longitudinal Studies

| Driver Category | Specific Factors | Data Source | Impact Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Opportunities | School quality, Academic tracking, Special programs | British National Child Development Study [10] | Strong influence on occupational skill qualifications in mid-adulthood |

| Health Considerations | Persistent poor health, Prenatal exposures, Chronic conditions | British National Child Development Study [10] | 30%+ reduction in educational performance; effects largely explained by early academic achievement |

| Family Structure | Parental resources, Sibling configuration, Caregiver availability | National Health and Aging Trends Study [11] | 90% of children live with familial caregivers when needed |

| Socioeconomic Status | Income, Parental education, Occupational status | Life course mobility models [10] | Compensatory (resource buffer) vs. exacerbation (loss of advantage) patterns |

Mechanisms Linking Early Health to Mobility and Attainment

Childhood health limitations significantly influence long-term educational and occupational outcomes through multiple pathways. The British National Child Development Study followed a cohort from birth through middle age, demonstrating that poor health before and during education predicts lower occupational skill qualifications in mid-adulthood [10]. These associations are particularly strong for children in persistently poor health rather than those with transient conditions.

The explanatory mechanism operates primarily through academic performance early in children's educational careers. Performance differentials emerge before the first important educational transition points, suggesting that health-related cognitive and non-cognitive skill development establishes trajectories that influence subsequent placement in educational tracks [10]. The relationship between specific prenatal exposures (e.g., maternal smoking) and mid-adulthood qualifications demonstrates particular persistence even after accounting for early academic performance.

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Studying Pediatric Mobility and Outcomes

| Method Type | Data Collection Approach | Analytical Technique | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Cohort | Follow cohorts from birth through adulthood (e.g., British NCDS) | Life course models, Path analysis, Structural equation modeling | Captures temporal ordering; establishes causality |

| Administrative Register | Link health, education, and tax records | Fixed effects models, Regression discontinuity | Large sample sizes; minimal recall bias |

| Time Use Surveys | 24-hour activity diaries (e.g., American Time Use Survey) | Time budget analysis, Sequence analysis | Captures daily routines; reveals trade-offs |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Mobility Research

Longitudinal Cohort Study Protocol

Objective: To examine the relationship between childhood health, educational mobility, and long-term socioeconomic attainment.

Population: Nationally representative birth cohort (e.g., British National Child Development Study with participants born in 1958) [10].

Data Collection Waves:

- Baseline: Prenatal period (maternal health behaviors, socioeconomic indicators)

- Childhood Assessments: Ages 7, 11, 16 (health limitations, cognitive testing, teacher evaluations)

- Early Adulthood: Age 23 (educational qualifications, first occupation)

- Mid-Life: Age 42 (occupational skill qualifications, income, health status)

Key Variables:

- Independent Variables: Persistent poor health (defined as health limitations at multiple assessment points), prenatal exposures (maternal smoking), socioeconomic background

- Mediating Variables: Academic performance at ages 7, 11, and 16; educational track placement; school absence

- Outcome Variables: Occupational skill qualifications in mid-adulthood coded using standardized classification

Analytical Approach: Path analysis with maximum likelihood estimation to test direct and indirect effects of childhood health on adult qualifications, controlling for socioeconomic background and testing for moderation effects.

Geographic Mobility and Caregiving Study Protocol

Objective: To quantify travel behavior changes among family caregivers of older adults.

Data Source: American Time Use Survey (ATUS) extracts covering a 9-year period, with daily time diaries from approximately 13,000 respondents including caregivers and non-caregivers [13].

Caregiver Identification: Respondents self-identifying as providing unpaid care for aging family members in the past 3-6 months.

Time Use Coding:

- Primary activities (e.g., direct care, medical care coordination)

- Travel time associated with care activities

- Simultaneous activities (e.g., care provision during travel)

Analytical Approach: Multivariate regression models controlling for employment status, household structure, race/ethnicity, and day of week, with separate models for male and female caregivers to test for gender differences in travel burdens.

Research workflow for life course mobility studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Life Course Mobility Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Instrument/Data Source | Application in Mobility Research |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Cohort Data | British National Child Development Study (NCDS) [10] | Tracking health-education linkages from birth to midlife |

| Time Use Surveys | American Time Use Survey (ATUS) [13] | Quantifying care-related travel burdens and time poverty |

| Health Assessment Tools | Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)/Instrumental ADLs scales [11] | Measuring functional limitations triggering mobility events |

| Administrative Registers | Swedish Population Registers [1] | Large-sample analysis of geographic mobility patterns |

| Mobility Metrics | Life-Space Mobility (LSM) assessment [12] | Evaluating mobility across different environmental zones |

| Geospatial Tools | Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) [14] | Harmonized definition of urban areas for cross-national comparison |

Older Adult Mobility: Health and Care Dynamics

Quantitative Patterns in Older Adult Mobility

Health triggers represent the primary driver of mobility in older populations, with distinct patterns emerging by severity of limitation. Analysis of Swedish register data demonstrates that severe health problems increase the likelihood of parents relocating closer to children or into institutions by 40-60%, but show no significant association with children moving closer to parents [1]. This asymmetry reflects the complex negotiation of care needs within family systems.

Gender patterning significantly structures older adult mobility, with mothers more likely to move toward daughters or toward distant children who have at least one sibling living nearby [1]. This reflects the well-documented gender division of care labor, where daughters provide more care, particularly for activities of daily living [11].

Table 4: Mobility Triggers and Patterns in Older Adults (80+)

| Mobility Type | Primary Triggers | Likelihood with Severe Health Problems | Gender Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Moves to Child | Widowhood, ADL limitations, Cognitive decline | 40-60% increase [1] | Mothers move toward daughters; relies on sibling proximity |

| Institutional Relocation | Multiple ADL limitations, High care needs, Cognitive impairment | Stronger than geographic convergence [1] | Women overrepresented due to longevity and higher disability rates |

| Child Moves to Parent | Parent health crises, Lack of local support, Only child status | No significant association [1] | Limited gender differentiation |

Conceptual Framework of Late-Life Mobility

Determinants of older adult mobility decisions

Integration and Implications for Research and Policy

The parallel high-mobility status of children and older adults reflects their shared structural position as dependent populations whose mobility decisions are made within constraints imposed by others' assessments of their needs and capabilities. For researchers and drug development professionals, this intersection presents several critical considerations:

Methodological implications include the need for longitudinal designs that capture mobility events in relation to key transition points, whether educational transitions for children or health transitions for older adults. The explanatory mechanisms differ substantially between these populations—while pediatric mobility influences outcomes primarily through educational opportunity structures, older adult mobility responds to declining functional capacity and care availability.

Intervention leverage points also differ across life stages. For children, policies addressing early identification of health and developmental limitations can mitigate negative educational consequences [10]. For older adults, supporting "aging in place" through assistive technologies and home modifications can reduce disruptive relocations while maintaining quality of life [12]. Both populations benefit from approaches that recognize mobility as embedded within family systems rather than individual decisions.

Future research should develop integrated models that track how early-life mobility experiences establish trajectories influencing later-life mobility patterns, creating potential pathways of cumulative advantage or disadvantage across the life course.

Socioeconomic and Geographic Disparities in Relocation Patterns

The study of relocation patterns represents a critical area of demographic research, particularly concerning two high-mover populations: children and older adults. While these groups exhibit elevated mobility rates, the underlying drivers, implications, and socioeconomic mediators differ substantially. Children typically move as dependents within family units responding to economic opportunities, housing adjustments, and community resources [15]. Older adults experience mobility driven by retirement transitions, health needs, and caregiving requirements [16]. Understanding the distinct relocation patterns of these demographics is essential for policymakers, urban planners, and public health professionals addressing the consequences of geographic mobility. This technical guide examines the socioeconomic and geographic disparities shaping relocation patterns, employing rigorous methodological frameworks to analyze moving behaviors and their impacts across the life course. The complex interplay between economic constraints, social policies, and developmental needs creates distinctive mobility signatures for these populations, requiring sophisticated analytical approaches to disentangle competing influences on relocation decisions.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Relocation Disparities

Economic Migration Theories

Traditional economic models frame migration decisions as rational calculations weighing expected benefits against costs [17]. These models prioritize employment opportunities, earnings differentials, and housing costs as primary drivers. Within this framework, families with children often relocate to optimize human capital development and long-term economic prospects [15], while older adults may move to maximize retirement resources or access age-specific amenities [16]. The declining geographic mobility observed across all age groups in recent decades suggests structural changes in these economic calculations, potentially due to dual-earner household constraints, housing market transformations, or regional convergence in wage premiums [17].

Life Course Perspective

The life course perspective provides a developmental framework for understanding age-graded mobility patterns. Transition points such as family formation, child-rearing, and retirement create mobility susceptibilities through changing housing needs and social obligations. For children, mobility is often involuntary and linked to parental socioeconomic status, with profound implications for developmental outcomes and opportunity structures [15]. Older adults face mobility decisions shaped by accumulating health limitations, changing social networks, and caregiving availability [16]. The life course approach emphasizes how historical context, such as pandemic disruptions or economic recessions, shapes these mobility transitions differently across birth cohorts.

Intersectional Inequality Framework

An intersectional framework acknowledges that relocation patterns reflect compounded advantages and disadvantages across multiple social axes [18]. Disparities emerge through intersecting identities of age, race, socioeconomic status, and migration history. This framework is particularly relevant for understanding the heightened vulnerabilities of certain subpopulations, such as migrant children [19] or economically disadvantaged older adults [20]. Research demonstrates how structural inequities in healthcare access, neighborhood opportunity, and social protection create systematically different mobility constraints and outcomes across population segments [18] [15].

Methodology for Analyzing Relocation Patterns

Table 1: Primary Data Sources for Analyzing Relocation Patterns

| Data Source | Population Coverage | Key Mobility Metrics | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Population Survey (CPS) [17] | U.S. households | Annual state-to-state migration rates; demographic and labor force characteristics | Large sample size; detailed demographic and economic variables | Does not capture reasons for move; limited contextual data |

| CDC WONDER Database [20] | U.S. mortality records | Geographic and demographic mortality variations | Detailed cause-of-death data; longitudinal tracking | Limited to mortality outcomes; no direct mobility measures |

| Redfin Platform Data [21] | Online home searchers | Anticipated migration through search patterns; housing cost data | Real-time behavioral data; geographic specificity | Selection bias toward housing-market participants |

| UN Migration Stock Data [19] | International migrants | Global migrant stocks by age and destination | Comparative international framework; child-specific estimates | Limited socioeconomic characteristics; infrequent updates |

Statistical Modeling Approaches

Multivariate regression models represent the primary analytical method for identifying factors predicting migration decisions. The standard protocol involves specifying a model with migration status as the dependent variable and a vector of independent variables capturing demographic characteristics, economic incentives, and geographic attributes [17] [21]. Model specification should control for age, marital status, labor force participation, homeownership, and parental status, with special attention to interaction effects capturing differential responses across subpopulations [17].

For temporal analysis of migration trends, researchers employ joinpoint regression to identify significant change points in time series data [20]. This method fits a series of connected straight lines to the migration rate data, testing whether each joinpoint (where trends change) is statistically significant. The protocol involves calculating Annual Percentage Changes (APCs) for each segment and overall Average Annual Percentage Changes (AAPCs) to quantify trend magnitudes.

Spatial analysis techniques incorporate geographic information systems to map migration flows and identify clustering of mobility patterns. These approaches are particularly valuable for detecting regional disparities and neighborhood-level effects on relocation decisions [21]. Spatial regression models can test whether migration patterns in proximate locations demonstrate autocorrelation, requiring specialized estimation techniques.

Experimental Workflow for Migration Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the systematic research workflow for analyzing relocation patterns:

Relocation Patterns in Child Populations

Demographic Trends and Disparities

Child relocation patterns reflect family responses to economic opportunities and constraints. Recent data indicates nearly 1 million additional children experiencing poverty following the reduction of pandemic-era social investments, exacerbating mobility-related stresses [15]. The Child Opportunity Index reveals stark disparities in neighborhood resources, with approximately 60% of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native children residing in lower-opportunity neighborhoods [15]. These geographic disparities in childhood resources create unequal developmental contexts with lifelong consequences for health, education, and economic mobility.

International child migration represents another significant dimension of relocation patterns. In 2020, 36 million children were international migrants, with 34 million refugees and asylum seekers forcibly displaced from their countries—half of them children [19]. The global migrant child population has increased by 50% since 1990, rising from 24 million to 36 million, creating urgent needs for specialized protection policies and integration services [19].

Socioeconomic Mediators of Child Mobility

Table 2: Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Child Relocation Patterns

| Factor | Impact on Mobility | Evidence | Disparity Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Opportunity | Families with resources move to higher-opportunity areas; constrained families remain in disadvantaged neighborhoods | 60% of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian children live in low-opportunity neighborhoods [15] | Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in access to high-opportunity areas |

| Housing Costs | High housing costs reduce mobility; families with children prioritize housing size and quality | Housing restrictions lowered U.S. GDP growth by 36% (1964-2009) [17] | Low-income families face severe constraints in high-opportunity areas |

| Child Care Accessibility | Families locate near relatives for child care; availability influences employment-related moves | Women living near parents experienced smaller earnings drops after having children [17] | Geographic variation in child care costs and availability |

| Parental Education | Highly educated parents cluster in cities with better schools and amenities | Geographic sorting by education with highly educated in large cities [17] | Intergenerational transmission of advantage through residential sorting |

Economic instability represents a powerful driver of child mobility, with families responding to employment shocks, housing cost pressures, and changing household composition. The end of pandemic-era child care funding has created a "funding cliff," exacerbating affordability challenges for working parents [15]. These economic pressures produce distinctive mobility patterns, including doubled-up households, frequent residential moves, and homelessness—each with documented negative consequences for child development and educational continuity.

Relocation Patterns in Older Adult Populations

Demographic Trends and Disparities

Older adult mobility reflects complex negotiations between health needs, economic resources, and social connections. America's rapidly aging population faces distinctive challenges, including increasing caregiving gaps as the traditional caregiver population (ages 45-64) shrinks relative to the oldest-old cohort [16]. By 2040, the caregiver ratio is projected to fall to 3:1 (from 6:1 in 2025), creating potential mobility pressures as older adults seek supportive environments [16].

Health disparities significantly shape later-life mobility patterns. Mortality from malnutrition and gastrointestinal cancers among older adults demonstrates striking racial and geographic variation, with Black or African American individuals experiencing rates of 5.3 per 100,000 compared to lower rates among other groups [20]. Alaska (7.1) and the Western United States (7.0) show the highest regional mortality rates, while nonmetropolitan areas consistently exceed metropolitan areas in age-adjusted mortality (4.0 vs. 3.3) [20]. These health gradients create distinctive mobility patterns as older adults seek appropriate medical care and support services.

Socioeconomic Mediators of Older Adult Mobility

Table 3: Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Older Adult Relocation Patterns

| Factor | Impact on Mobility | Evidence | Disparity Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiving Availability | Older adults move closer to family care; or to facilities when family unavailable | 69% of older adults receive only informal care; 5% receive only formal care [16] | Childless older adults rely more on siblings and other relatives |

| Health Infrastructure | Mobility toward areas with better healthcare services; away from underserved areas | Mortality from malnutrition/GI cancer rising since 2013 (APC: 11.6) [20] | Rural-urban disparities in healthcare access and outcomes |

| Housing Affordability | Constrained mobility despite changing needs; aging in place without appropriate modifications | Households less responsive to housing costs; prefer to stay [17] | Low-income older adults face worst housing-cost burdens |

| Social Isolation | Mobility decisions influenced by social network preservation; relocation can disrupt ties | Socially isolated older adults face greater risk of early death, dementia, heart disease [16] | Black Americans, poverty populations, sexual/gender minorities experience higher isolation |

The dramatic growth of Medicare Advantage plans (enrolling 54% of older adults in 2024, up from 19% in 2007) has created new constraints on mobility through network restrictions and service area limitations [16]. Simultaneously, family caregiving demands have intensified, with time spent assisting older adults with dementia increasing by almost 50% between 2011 and 2022 (from 21 to 31 hours weekly) [16]. These competing pressures—institutional constraints versus family resources—create complex mobility decisions for older households.

Research Reagents and Analytical Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Studying Relocation Patterns

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Population Survey (CPS) | Provides annual migration flows with demographic and economic covariates | Analyzing declining interstate migration trends by age, marital status, and labor force participation [17] | Annual sample size ~50,000 households; includes geographic mobility supplement |

| CDC WONDER Database | Analyzes mortality trends by geographic and demographic characteristics | Tracking malnutrition and GI cancer mortality disparities by region and race [20] | Underlying cause-of-death data with multiple demographic stratifiers |

| Joinpoint Regression Software | Identifies significant trend change points in temporal data | Determining when mortality trends reversed from decline to increase [20] | National Cancer Institute software; tests up to 3 joinpoints |

| Child Opportunity Index | Measures neighborhood resources affecting child development | Documenting racial/ethnic disparities in access to high-opportunity neighborhoods [15] | Composite index of 29 indicators across education, health, environment domains |

| Redfin Platform Data | Captures housing search behavior indicating anticipated migration | Analyzing factors influencing planned moves across metropolitan areas [21] | Search data from major real estate platform; geographic and temporal variation |

Advanced research approaches incorporate biomarker data, wearable sensors, and geographic information systems to capture multidimensional influences on mobility behavior [16]. Biomarker collection through blood and other medical tests offers insights into physiological processes linking stress, environmental conditions, and relocation decisions. Wearable devices can track social interactions and physical mobility, providing real-time behavioral data to complement traditional survey measures. These methodological innovations enable more precise measurement of the mechanisms connecting socioeconomic status, geographic context, and relocation outcomes.

Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in relocation patterns for children and older adults reflect structural inequities with profound implications for health, economic security, and intergenerational mobility. Children's mobility is largely involuntary, embedding them in opportunity structures with lasting developmental consequences [15]. Older adults face mobility decisions constrained by accumulating health limitations, caregiving availability, and fixed incomes [16]. Both populations demonstrate heightened vulnerability to policy shocks, economic downturns, and environmental disruptions, requiring targeted interventions to address their distinctive needs.

Research indicates promising policy directions, including strengthened social protection systems, investment in community infrastructure, and anticipatory governance approaches that recognize the intersecting dimensions of demographic disadvantage [18]. For children, expanding access to high-opportunity neighborhoods through housing assistance and community investment may mitigate relocation-driven disparities [15]. For older adults, developing comprehensive long-term care systems while supporting family caregivers may create more sustainable mobility options [16]. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs that capture mobility trajectories across the life course, integrate biological and social determinants, and evaluate policy interventions addressing the structural drivers of relocation disparities.

Research Design and Pharmacovigilance in Dynamic Populations

Designing Robust Longitudinal Studies with Mobile Cohorts

Longitudinal studies, which employ continuous or repeated measures to follow particular individuals over prolonged periods of time—often years or decades—provide invaluable insights into developmental trajectories, health outcomes, and the long-term effects of interventions. [22] However, their implementation faces particular methodological challenges when studying high-mover populations, such as children and older adults, who experience frequent residential transitions or inherent instability in their living situations.

For children, factors including family dynamics, parental career changes, economic pressures, and housing instability can create frequent relocations. [23] Among older adults, transitions may be driven by health declines, financial constraints, moving to be closer to family support, or entering care facilities. [24] These mobility patterns threaten longitudinal research through attrition bias and interrupted data collection, potentially compromising the validity of findings. This guide provides technical methodologies for maintaining robust data collection with these mobile cohorts.

Core Methodological Framework

Defining Longitudinal Study Designs

Longitudinal research employs continuous or repeated measures to follow individuals over prolonged periods, enabling researchers to identify and relate events to particular exposures, establish sequences of events, and follow change over time within particular individuals. [22] Several design variants exist:

- Prospective Cohort Studies: Same participants followed over time, with data collected before relevant outcomes occur. [22]

- Repeated Cross-Sectional Studies: Different participants sampled from the same population at each time point. [22]

- Linked Panel Studies: Data collected for other purposes is linked to form individual-specific datasets. [22]

Table 1: Advantages and Disadvantages of Longitudinal Designs

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Establish sequence of events | Participant attrition and loss to follow-up |

| Track individual change over time | Difficulty separating reciprocal exposure-outcome impact |

| Reduce recall bias through prospective data collection | Increased temporal and financial demands |

| Account for cohort, period, and age effects | Requires robust infrastructure to withstand time challenges |

Special Considerations for Mobile Cohorts

Mobile populations present unique methodological challenges that require specialized approaches:

- Infrastructure Stability: The research infrastructure must maintain consistent data collection methods across multiple geographic locations and withstand the test of time. [22]

- Remote Engagement: Technologies must enable continued follow-up despite participant relocation, requiring flexible, location-independent assessment methods. [24]

- Standardized Protocols: Data collection and recording methods must be identical across study sites and consistent over time to maintain data integrity. [22]

- Unique Identification Systems: All information pertaining to particular individuals must be linked through robust coding systems that persist despite location changes. [22]

Implementation Strategies for Mobile Cohorts

Digital Data Collection Framework

Modern longitudinal studies increasingly leverage digital technologies to maintain contact with mobile participants, though this introduces considerations regarding the digital divide—disparities in digital technology access, usage, and outcomes. [24]

Table 2: Operationalizing Digital Data Collection

| Component | Implementation Method | Mobile Cohort Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Access | Provision of tablets/smartphones with data plans | Addresses access gaps prevalent among lower socioeconomic groups [24] |

| e-Communication | Health portals, messaging platforms, virtual visits | Requires training to overcome usage gaps, particularly among older adults [24] |

| Cognitive Support | Digital literacy training, simplified interfaces | Mitigates self-efficacy gaps in information seeking [24] |

| Remote Monitoring | Wearable sensors, mobile health apps | Enables continuous data collection despite geographic mobility |

Research indicates that while digital access gaps are decreasing over time (OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.78, 0.94), disparities persist particularly among older adults with lower education and income, and those identifying as Hispanic. [24] These patterns must be considered when implementing digital frameworks with mobile cohorts.

Retention Protocols for High-Mover Populations

Successful longitudinal studies with mobile cohorts implement systematic retention strategies:

- Preemptive Location Tracking: Collect multiple contact methods (email, phone, addresses of close relatives) at baseline and update regularly.

- Minimized Participant Burden: Streamline data collection procedures and offer flexible assessment scheduling to maintain participation during transitions.

- Maintained Engagement: Regular, low-stakes contact between major assessment waves (newsletters, holiday cards, small incentives).

- Exit Interviews: Conduct detailed interviews with participants leaving the study to understand reasons for attrition and improve protocols. [22]

Data Analysis Considerations

Statistical Approaches for Longitudinal Data

Analyzing longitudinal data requires specialized statistical approaches that account for the correlated nature of repeated measurements within individuals. Common methods include:

- Mixed-Effect Regression Models (MRM): Focus on individual change over time while accounting for variation in timing of measures and missing data. [22]

- Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Models: Rely on independence of individuals within populations to focus primarily on regression data. [22]

- Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA): Compares means across groups but sacrifices individual-specific data. [22]

A critical consideration is avoiding repeated hypothesis testing as would be applied to cross-sectional studies, as this leads to underutilization of data, underestimation of variability, and increased likelihood of Type II errors. [22]

Handling Missing Data from Mobile Cohorts

With mobile populations, missing data is inevitable and requires sophisticated handling:

- Missing Data Mechanism Analysis: Determine whether data is missing completely at random (MCAR), at random (MAR), or not at random (MNAR).

- Multiple Imputation Techniques: Create several complete datasets by imputing missing values, analyzing each, then combining results.

- Sensitivity Analyses: Test how different assumptions about missing data affect study conclusions.

Table 3: Bayesian Synthesis Approach for Multi-Cohort Data (Example) [25]

| Research Phase | Methodological Action | Outcome for Mobile Cohorts |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Cohort Analysis | Evaluate competing hypotheses within each cohort using appropriate statistical models | Maintains cohort-specific context while preparing for synthesis |

| Evidence Aggregation | Apply Bayesian methods to synthesize findings across diverse cohorts | Enables robust conclusions supported by all data sources despite mobility |

| Robustness Assessment | Test whether conclusions hold across all measurement approaches and cohorts | Provides confidence in findings despite missing data patterns |

The Bayesian research synthesis approach has been successfully demonstrated in multi-cohort developmental studies, such as research on self-control development during adolescence that aggregated evidence across three Dutch cohorts with different measures to arrive at robust conclusions. [25]

Case Study: Framingham Heart Study Adaptations

The Framingham Heart Study, initiated in 1948, represents the quintessential longitudinal study that has evolved methodologies to maintain engagement with a mobile population. [22] Originally following 5,209 subjects from Framingham, Massachusetts, the study faced challenges of geographical mobility over its decades-long duration.

Key adaptations for mobility management included:

- Multi-Generational Recruitment: Engaging children and grandchildren of original participants to maintain family linkages despite geographic dispersal.

- Decentralized Assessment Sites: Establishing satellite data collection centers to accommodate participant movement beyond the original community.

- Periodic Intensive Follow-Ups: Implementing focused tracking efforts to re-establish contact with lost participants at regular intervals.

- Flexible Data Collection Modalities: Evolving from purely in-person assessments to incorporate mail, telephone, and eventually digital data collection.

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Mobile Cohort Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Mobile Context |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Tracking Systems | REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), custom CRM databases | Maintain contact information across geographic transitions |

| Digital Assessment Platforms | Tablet-based surveys, mobile health apps, web-based cognitive tests | Enable continuous data collection despite location changes |

| Remote Sensing Technologies | Wearable activity monitors, smartphone sensors, GPS trackers | Passively capture data without requiring participant location |

| Communication Tools | Secure messaging platforms, virtual meeting software, automated reminder systems | Maintain engagement through preferred communication channels |

| Data Integration Systems | API-based data pipelines, cloud storage solutions, blockchain for data integrity | Aggregate data from multiple sources and locations securely |

Designing robust longitudinal studies for mobile cohorts requires intentional methodological planning from inception through analysis. By implementing flexible digital frameworks, proactive retention strategies, and appropriate statistical approaches that account for mobility-related challenges, researchers can maintain data integrity and generate valid findings even with high-mover populations like children and older adults. The strategic integration of technology, methodological rigor, and participant-centered protocols enables successful longitudinal investigation despite the inherent mobility of these populations.

Mitigating Attrition and Loss to Follow-up in Clinical Trials

Attrition, or loss to follow-up, presents a significant threat to the integrity and validity of longitudinal clinical research. It negatively affects statistical power, disrupts the random composition of groups, and can produce unwanted bias that compromises both internal and external validity [26]. The problem is particularly acute for special populations, including children and older adults, who experience unique challenges that make them high-attrition populations in clinical research. This technical guide examines the specific factors contributing to attrition in these vulnerable groups and provides evidence-based methodologies for mitigating these challenges throughout the clinical trial lifecycle.

For children, study participation inherently involves complex dynamics between the child, caregivers, and research staff. In pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) research, completers had significantly higher primary caregiver education and family income than non-completers, highlighting how socioeconomic factors indirectly impact a child's ability to remain in studies [26]. For older adults, a longitudinal aging study found attrition was most likely to occur in participants who were older, male, inactive, socially isolated, and cognitively impaired [27]. Understanding these population-specific vulnerabilities is essential for designing retention strategies that address the fundamental causes of attrition.

Quantifying the Attrition Challenge: Comparative Data Across Populations

Table 1: Attrition Rates Across Different Clinical Trial Populations

| Population | Attrition Rate | Time Frame | Key Predictors of Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric TBI [26] | 20-60% | Long-term follow-up | Lower caregiver education, lower family income, higher injury severity |

| Older Adults [28] | Up to 40% | 2-year follow-up | Age, smoking, frailty, lower education, racial minority status |

| Postmenopausal Women [28] | 30.2% | 6-year follow-up | Age, smoking, frailty, lower educational level, race, hospitalization, poorer quality of life |

| Pediatric Obesity [29] | 33-51% | 12-month follow-up | Lower parental education, less structured home environment, lower treatment success |

| Neonatal Research [30] | 11% | 12-month follow-up | Less maternal education, more people in household, public insurance |

Table 2: Comparative Predictors of Attrition in Pediatric vs. Geriatric Populations

| Factor Category | Pediatric Populations | Geriatric Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | Lower parental education [26] [30], Lower family income [26], Public insurance [30] | Lower educational level [28] [27], Lower socioeconomic status [28] |

| Clinical | Higher injury severity [26], Less success during treatment [29] | Cognitive impairment [27], Frailty [28], Worse self-rated health [27], Polypharmacy [28] |

| Social/Environmental | More people in household [30], Less structured eating environment [29] | Social isolation [27], Leaving house less often [27], No engagement in social activities [27] |

| Behavioral | Not significant in most studies | Smoking [28], No physical activity [27] |

Methodological Framework for Understanding Attrition

Statistical Considerations and Impact Analysis

The statistical implications of attrition extend beyond simple sample size reduction. Attrition disrupts the random composition of groups, potentially introducing confounding influences and threatening both internal validity (through disruption of group randomization) and external validity (by making data less generalizable) [26] [29]. The fragility of trial results due to patients lost to follow-up can be quantified using specialized statistical measures. The LTFU-aware fragility index is a recently developed metric that determines the number of lost patients who must have outcomes different than expected based on the observed patients to reverse statistical significance [31]. This approach allows researchers to rigorously explore how the outcomes of patients lost to follow-up could potentially alter trial conclusions.

Population-Specific Vulnerability Assessment

Children and older adults share similar vulnerabilities despite being at opposite ends of the age spectrum. Both groups often depend on caregivers for participation, face unique physiological considerations, and experience barriers related to autonomy and communication. For pediatric populations, the burden of participation falls on both the child and caregivers, with socioeconomic factors creating substantial barriers to ongoing engagement [26] [29]. For older adults, physiological changes, comorbidities, and social isolation create distinct challenges for trial participation and retention [27] [32].

Historical context and trust issues significantly impact participation in special populations. Older adults from minority communities may harbor mistrust rooted in historical unethical research practices, while parents of pediatric participants may struggle with logistical and financial burdens that disproportionately affect retention in lower-income households [33]. Understanding these contextual factors is essential for designing effective retention strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Retention

Retention Strategies for Pediatric Populations

Effective retention in pediatric trials requires addressing both the child's needs and caregiver barriers. In a pediatric traumatic brain injury study, researchers provided all participating families with high-speed Internet access for the first 6 months and a desktop computer to address potential disparities in Internet access and utilization [26]. This technological support was complemented by financial compensation for time spent completing assessments ($10, $50, and $35 for the 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-ups, respectively).

In neonatal research, implementing intensive tracking measures and maintaining consistency of study procedures have shown success in improving participant retention [30]. Research coordinators in the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) study estimated the likelihood of attrition before discharge and used this assessment to target additional support to high-risk families. The study also employed structured satisfaction surveys to identify and address family concerns early in the participation process [30].

Retention Strategies for Older Adult Populations

Retention of older adults requires addressing physical, cognitive, and social barriers to participation. Decentralized clinical trial (DCT) elements show particular promise for this population, with 74% of older adults preferring remote participation options over in-person clinic visits [32]. Implementing frontier sites at local pharmacies and clinics in community-accessible locations can significantly reduce transportation challenges.

Social isolation is a critical factor in older adult attrition. Studies show that participants not living with another study participant, those with limited social activities, and those who leave the house less frequently are at higher risk of attrition [27]. Addressing these factors through regular social contact from research staff, incorporating study activities into social routines, and creating opportunities for social connection within the trial context can improve retention.

Engagement strategies must also account for technological access and literacy among older adults. While digital solutions offer convenience, they must be implemented with appropriate support for participants with limited digital experience. This may include telephone-based alternatives, in-person technology assistance, and simplified digital interfaces designed for older users [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Attrition Mitigation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Tracking | Intensive tracking protocols | Identify at-risk participants early for targeted intervention | [26] [30] |

| Multiple contact methods (phone, email, mail) | Maintain communication channels for hard-to-reach participants | [28] [30] | |

| Data Collection | Decentralized clinical trial (DCT) technologies | Reduce participant burden through remote data collection | [32] |

| Wearable devices and remote monitoring | Capture objective data without requiring site visits | [32] | |

| Participant Support | Financial compensation structures | Offset participation costs and acknowledge participant time | [26] [29] |

| Technology provision (internet, devices) | Address digital divide and access disparities | [26] [32] | |

| Analytical Tools | LTFU-aware fragility indices | Quantify robustness of trial results to missing data | [31] |

| Multiple imputation techniques | Handle missing data statistically to reduce bias | [28] [31] |

Integrated Retention Workflow and Implementation Framework

Mitigating attrition in clinical trials requires a sophisticated, multi-faceted approach that addresses the unique challenges faced by high-attrition populations such as children and older adults. The evidence demonstrates that successful retention strategies must begin at study design and continue through implementation, monitoring, and analysis phases. By understanding the population-specific factors that contribute to attrition—from socioeconomic barriers in pediatric populations to social isolation and physical limitations in older adults—researchers can develop targeted interventions that maintain participant engagement throughout the trial lifecycle. The integration of technological solutions, appropriate statistical methods for handling missing data, and proactive relationship-building creates a comprehensive framework for reducing attrition and ensuring the validity and generalizability of clinical trial results across all populations.

Pharmacovigilance, defined as the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), represents a critical component of post-marketing drug safety surveillance [34]. Within this domain, the persistent challenge of underreporting disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, particularly children and older adults, who constitute high-risk populations for several physiological and methodological reasons. These groups experience unique pharmacological challenges; pediatric patients often receive drugs prescribed off-label or unlicensed due to their exclusion from clinical trials, while older adults experience age-related physiological changes and polypharmacy that increase their susceptibility to ADRs [35] [34] [36].

The convergence of limited clinical trial data for special populations and systemic underreporting creates significant gaps in drug safety profiles. Underreporting is a pervasive issue worldwide, with estimates suggesting that over 94% of ADRs go unreported by healthcare professionals [37]. This whitepaper examines the particular challenges of ADR underreporting in mobile health and rural contexts, framed within the broader thesis of pediatric and geriatric vulnerabilities, and proposes structured methodologies and technological solutions to enhance pharmacovigilance systems for these demographically and geographically underserved subgroups.

Physiological and Methodological Vulnerabilities in High-Risk Populations

Pediatric Vulnerabilities

Children are not merely "small adults" from a pharmacological perspective. Their dynamic physiological development significantly alters drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Key factors contributing to their classification as a high-risk population include:

- Off-label and Unlicensed Prescribing: Pediatric medication use frequently occurs outside the specifications of the marketing authorization due to the exclusion of children from clinical trials [35] [38].

- Developing Physiological Systems: Immature metabolic enzymes, renal excretion mechanisms, and changing body composition ratios result in unpredictable drug distribution and elimination patterns [34].

- Atypical ADR Presentations: Adverse reactions in children may manifest differently than in adults, often with non-specific symptoms that are easily misattributed to common childhood illnesses [35].

Geriatric Vulnerabilities

The aging process introduces another set of complex pharmacological challenges that extend beyond chronological age:

- Polypharmacy: Older adults frequently manage multiple chronic conditions, leading to the concurrent use of five or more medications. This dramatically increases the risk of drug-drug interactions and cumulative ADRs [36].

- Age-Related Physiological Changes: Reduced hepatic metabolism, declining renal function, altered body composition (increased fat-to-muscle ratio), and changes in gastrointestinal absorption collectively alter drug effects [36].

- Frailty as a Better Predictor: Contemporary research suggests that frailty status, more than age alone, better predicts ADR risk. Frail older patients are twice as likely to experience ADRs compared to non-frail patients, yet this parameter is rarely captured in current pharmacovigilance systems [39].

- Atypical Presentations: ADRs in older adults often present with non-specific geriatric syndromes such as falls, confusion, delirium, or functional decline, which are frequently misattributed to aging or comorbid conditions rather than medication effects [36].

Quantitative Assessment of Underreporting Challenges

The following tables synthesize empirical data on the scope and nature of underreporting across different contexts and populations.

Table 1: Documented Underreporting Rates and Primary Barriers in Different Settings

| Setting/Population | Underreporting Rate/Level | Primary Identified Barriers | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Professionals (General) | >94% of ADRs unreported | Lack of time, uncertainty about causation, complacency, perception that only serious ADRs need reporting | [37] |

| Pediatricians (Netherlands) | 19% had never reported an ADR | Prior knowledge of ADR (61%), uncertainty if symptom was ADR, lack of severity, time constraints | [35] [38] |

| Patients/Consumers (General) | Represents only ~9% of total reports | Ignorance of reporting systems, complacency, lethargy, low health literacy | [37] |

| Rural Settings (Mozambique) | Qualitative reporting challenges | Poor telecommunications, transportation limitations, remote location, low education levels | [40] |

Table 2: Effectiveness of Mobile Health Applications in Enhancing ADR Reporting

| Mobile Application | Region/Country | Key Efficacy Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MedWatcher | United States | High VigiGrade completeness score (averaging 0.80); 55.9% well-documented | N/R |

| My eReport France | France | High clinical quality score in ClinDoc tool; 36% well-documented | p = 0.002 |

| WEB-RADR (Yellow Card) | United Kingdom | Better reporting rates among patients compared to conventional methods | p < 0.01 |

| ADR Reporting App | India | Significantly better completeness score than paper-based systems | p < 0.001 |

| Med Safety | 13 African countries | Missing information: 0% (vs. 29.6% for paper-based CIOMS forms) | N/R |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Addressing Underreporting

Protocol 1: Implementing Spontaneous Reporting in Resource-Limited Rural Settings

Background: Based on the Mozambique study, this protocol outlines a framework for establishing spontaneous reporting systems in rural districts with infrastructure challenges [40].

Methodology:

- Training Program Development:

- Conduct intensive training sessions for all levels of healthcare workers (including those with basic training)

- Utilize standardized ADR reporting forms ("yellow card" system)

- Focus on ADR diagnosis, treatment, and reporting procedures

- Training duration: 1-2 days with refresher sessions

Implementation Framework:

- Identify and appoint focal persons in each district to facilitate communication with the National Pharmacovigilance Unit (NPU)

- Establish routine quality-assurance site visits (monthly initially, then quarterly)

- Implement supportive supervision to identify and clarify problems in form completion and submission

- Develop simplified reporting forms with visual aids for low-literacy settings