Integrating Protocol Analysis with Neuroimaging: A Multimodal Framework for Advancing Design Neurocognition

This article explores the synergistic integration of protocol analysis—a traditional method for studying designers' verbalized thoughts—with modern neuroimaging techniques to advance the field of design neurocognition.

Integrating Protocol Analysis with Neuroimaging: A Multimodal Framework for Advancing Design Neurocognition

Abstract

This article explores the synergistic integration of protocol analysis—a traditional method for studying designers' verbalized thoughts—with modern neuroimaging techniques to advance the field of design neurocognition. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of the foundational principles, methodological applications, and common challenges of this multimodal approach. The content covers the triangulation of data from designers' minds (cognition), bodies (physiology), and brains (neurocognition) to yield a more holistic understanding of complex design processes. It further discusses validation strategies and comparative analyses with other study designs, concluding with future directions and implications for fostering innovation and improving reproducibility in biomedical research and clinical trials.

The Foundations of Design Neurocognition: Bridging Minds and Brains

The triangulation framework for studying complex cognitive processes integrates simultaneous measurements from three distinct paradigmatic approaches: the mind (cognition), the body (physiology), and the brain (neurocognition). This methodological paradigm provides a comprehensive, multi-level understanding of human cognition that transcends the limitations of single-method investigations. In the context of design neurocognition research, this framework enables researchers to capture the rich, dynamic interplay between different cognitive systems during design thinking activities [1]. The core premise of triangulation is that by converging data from these three complementary sources, researchers can develop a more veridical and complete model of cognitive phenomena, moving beyond descriptive accounts to mechanistic explanations grounded in objective physiological and neural evidence [2] [1].

The application of this framework is particularly valuable for studying design thinking—a complex cognitive activity characterized by ill-defined problems, co-evolution of problem and solution spaces, and the integration of diverse reasoning modalities [1]. Traditional design research methods, such as protocol analysis, have provided valuable insights into design cognition but remain limited to external manifestations of internal cognitive processes. By incorporating physiological and neurocognitive measures, researchers can now access implicit, non-conscious, and automatic aspects of design thinking that may not be accessible through verbal reports alone [2] [1]. This integrated approach is transforming design research by providing new avenues to investigate the neurocognitive foundations of creativity, innovation, and problem-solving in both educational and professional contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Relevance to Design Neurocognition

The Three Pillars of Triangulation

The triangulation framework establishes three interconnected pillars of investigation:

- Design Cognition (Mind): This pillar focuses on the study of cognitive processes underlying design thinking, including reasoning patterns, problem-solving strategies, creativity, and decision-making. Investigated primarily through protocol analysis, black-box experiments, surveys, and interviews, this approach provides direct insight into the conceptual processes designers employ when tackling complex problems [1]. The analysis of verbalized thoughts reveals how designers frame problems, generate solutions, and navigate the problem-solution space through various reasoning mechanisms.

Design Physiology (Body): This dimension investigates physiological manifestations of cognitive processes during design activities. Measured through tools such as eye tracking, electrodermal activity (EDA), heart rate variability (HRV), and emotion tracking, physiological data provide continuous, objective indicators of cognitive states without requiring verbal interruption [1]. These measures reveal how cognitive effort, emotional arousal, visual attention, and autonomic nervous system engagement fluctuate throughout the design process, offering insights into the embodied nature of design cognition.

Design Neurocognition (Brain): This pillar examines the neural correlates and mechanisms supporting design thinking using non-invasive brain imaging technologies. Techniques including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) capture brain activity during design tasks, localizing cognitive functions to specific neural circuits and networks [2] [1]. This approach provides information about the temporal dynamics and spatial organization of brain systems engaged during different aspects of design thinking, from conceptual generation to evaluation.

Philosophical and Methodological Underpinnings

The triangulation framework is grounded in the philosophical assumption that complex cognitive phenomena like design thinking emerge from the dynamic interaction of multiple systems operating at different levels of analysis. Rather than reducing cognition to any single level, the framework embraces a multi-level explanatory approach that seeks to establish convergent validity across different measurement modalities [1]. This methodological pluralism acknowledges that each approach possesses inherent strengths and limitations—while design cognition methods offer direct access to verbalized thoughts, they are susceptible to reporting biases; physiological measures provide continuous objective data but require inference to link to cognitive states; and neurocognitive techniques localize brain activity but often sacrifice ecological validity for experimental control [2].

The framework's application to design neurocognition specifically addresses the situated and embodied nature of design activity. Design thinking is not merely a disembodied cognitive process but is fundamentally grounded in perceptual-motor interactions with the environment and mediated by affective and physiological states [1]. By simultaneously capturing data across multiple channels, researchers can investigate how these different systems interact in real-time during authentic design tasks, preserving the ecological validity that is often compromised in traditional laboratory studies of cognition. This approach has already yielded new insights into the cognitive processes underlying design creativity, including the identification of distinct patterns of brain activation associated with different stages of the design process and the physiological correlates of creative flow states [2].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Comprehensive Multi-Modal Data Acquisition Protocol

Objective: To simultaneously capture cognitive, physiological, and neurocognitive data during design thinking tasks. Primary Applications: Studying cognitive processes in design creativity, problem-solving, and professional design practice.

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation (Approximately 45 minutes)

- Apply EEG cap according to the 10-20 international system, ensuring electrode impedances are below 5 kΩ.

- Attach EDA electrodes to the palmar surface of the non-dominant hand's index and middle fingers.

- Position HRV sensors on the participant's chest using a Polar H10 sensor or equivalent.

- Calibrate eye tracking system (e.g., Tobii Pro Spectrum) using a 5-point calibration procedure.

- For fMRI studies, screen for contraindications and familiarize participants with the scanning environment.

Experimental Task Setup (Approximately 15 minutes)

- Present design brief detailing the problem context, constraints, and deliverables.

- Explain think-aloud protocol instructions, emphasizing continuous verbalization without self-censoring.

- Conduct a short practice session (5 minutes) to familiarize participants with simultaneous thinking aloud while physiological and neural data are collected.

Data Synchronization Implementation

- Implement a common trigger signal across all recording systems to ensure temporal alignment of data streams.

- Use Lab Streaming Layer (LSL) or similar synchronization framework to timestamp all data sources.

- Record synchronization pulses at the beginning and end of each experimental condition.

Experimental Session (60-90 minutes)

- Conduct design task under one of three conditions: open-ended problem, constrained problem, or problem with inspirational stimuli [2].

- Record continuous measures throughout the session:

- Audio and video for subsequent protocol analysis

- EEG data (512-1024 Hz sampling rate)

- fNIRS data (10 Hz sampling rate) for prefrontal cortex activation [2]

- Eye tracking data (60-120 Hz sampling rate)

- EDA and HRV (64 Hz sampling rate)

Data Collection Completion

- Administer post-task interviews and questionnaires to capture retrospective reports.

- Debrief participants about their design experience and strategy.

Application Notes:

- This protocol is particularly suited for investigating the neurocognitive basis of design creativity and has been successfully implemented in studies examining differences between expert and novice designers [2] [1].

- For optimal data quality, minimize participant movement during EEG and fNIRS recordings, though fNIRS is more tolerant of motion artifacts than fMRI [2].

- The synchronization of multiple data streams is technically challenging but essential for subsequent correlation analysis across different measurement modalities.

Protocol Analysis and Verbal Data Coding Procedure

Objective: To extract and categorize cognitive processes from verbal protocols obtained during design tasks. Primary Applications: Analysis of design reasoning, problem-solving strategies, and cognitive processes in design.

Procedure:

- Verbal Data Transcription

- Transcribe audio recordings verbatim, including non-lexical utterances (e.g., "um," "ah").

- Segment transcripts into meaningful units based on grammatical clauses or idea completeness.

Coding Scheme Development

- Adopt established coding schemes from design research, such as the FBS ontology or Gero's design prototypes [1].

- Define explicit coding rules with examples and non-examples for each category.

- Train multiple coders to achieve inter-coder reliability of Cohen's κ > 0.8 before formal analysis.

Segmentation and Coding Process

- Segment transcripts into the smallest meaningful units of analysis (typically 5-15 words).

- Assign appropriate codes to each segment based on the coding scheme.

- Conduct reliability checks on at least 20% of the data with multiple coders.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate frequency and duration of different cognitive activities.

- Construct transition matrices to identify sequential patterns in design reasoning.

- Identify critical incidents and strategy shifts in the design process.

Application Notes:

- This procedure enables researchers to identify characteristic design thinking patterns such as problem framing, solution generation, and evaluation [1].

- The coded protocol data can be temporally aligned with physiological and neurocognitive measures to create integrated multi-level datasets.

- Combining segmentation approaches (time-based and content-based) can provide complementary insights into the design process.

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Analysis Protocol for Design Tasks

Objective: To capture and analyze neural correlates of design thinking using appropriate neuroimaging modalities. Primary Applications: Localizing design cognition in the brain, identifying neural networks supporting creativity.

Procedure:

- Imaging Modality Selection

Task Design Implementation

- Implement block designs for robust detection of neural activity associated with sustained cognitive states.

- Utilize event-related designs for isolating neural responses to specific design events or stimuli.

- Incorporate appropriate control conditions (e.g., rest, perceptual tasks, problem-solving) [2].

Data Acquisition Parameters

- For fMRI: Use T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (TR=2000 ms, TE=30 ms, voxel size=3×3×3 mm).

- For EEG: Record from 64+ channels with sampling rate ≥512 Hz, online filters 0.1-100 Hz.

- For fNIRS: Position optodes over prefrontal and parietal regions based on the 10-20 system.

Data Preprocessing

- For fMRI: Implement standard preprocessing pipeline (realignment, normalization, smoothing).

- For EEG: Apply filters (0.5-40 Hz), remove ocular artifacts, re-reference to average.

- For fNIRS: Convert raw light intensity to oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations.

Statistical Analysis

- Conduct whole-brain analysis to identify task-related activations/deactivations.

- Perform connectivity analysis (PPI, ICA) to identify functional networks.

- Implement machine learning approaches for multivariate pattern analysis [3].

Application Notes:

- Previous studies using this approach have revealed that design thinking engages prefrontal cortex regions differently than standard problem-solving tasks [2].

- EEG studies have shown that higher alpha-band activity over temporal and occipital regions distinguishes between open-ended and close-ended problem descriptions during design problem-solving [2].

- Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is particularly valuable for design neurocognition studies as it allows participants to freely move, speak, and interact with design materials during data collection [2].

Data Analysis and Integration Framework

Multi-Modal Data Integration Methodology

The triangulation framework requires specialized analytical approaches to integrate data across different levels of analysis. The integration methodology proceeds through three sequential phases:

Temporal Alignment and Preprocessing

- Apply interpolation and filtering to address different sampling rates across modalities

- Identify and remove motion artifacts and other technical noise sources

- Segment data into epochs corresponding to specific design phases or events

Within-Modality Analysis

- Conduct protocol analysis to identify cognitive segments and sequences

- Perform standard statistical analyses for neuroimaging data (GLM, connectivity)

- Analyze physiological data for arousal, attention, and emotional indicators

Cross-Modal Correlation and Predictive Modeling

- Compute correlation between neural/physiological measures and coded cognitive activities

- Implement machine learning approaches to predict cognitive states from neural/physiological data [3]

- Identify temporal precedence and potential causal relationships using methods like Granger causality

This integrated analytical approach has revealed that distinct patterns of brain activation differentiate design tasks from standard problem-solving, with design thinking preferentially engaging prefrontal cortical regions [2]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that EEG patterns can distinguish between different cognitive processes in design, corroborating behavioral evidence from protocol analysis [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

Table 1: Technical specifications and applications of major neuroimaging modalities in design neurocognition research

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications in Design Research | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | High (1-3 mm) | Low (seconds) | Localizing design cognition neural correlates; comparing design with problem-solving [2] | Excellent spatial resolution; whole-brain coverage | Poor temporal resolution; restrictive environment |

| EEG/ERP | Low (cm) | High (ms) | Tracking rapid cognitive shifts during designing; measuring effort and concentration [2] [1] | Millisecond temporal resolution; portable systems available | Poor spatial resolution; sensitive to artifacts |

| fNIRS | Moderate (1-2 cm) | Moderate (seconds) | Studying design in naturalistic settings; measuring cortical activation during realistic tasks [2] | Tolerant of movement; quiet operation | Limited to cortical surfaces; shallow penetration |

| Eye Tracking | High (1° visual angle) | High (ms) | Studying visual attention in design; analyzing design perception and fixation [1] | Direct measure of overt attention; naturalistic measurement | Does not capture covert attention |

Experimental Reagents and Research Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and equipment for triangulation studies in design neurocognition

| Research Tool | Specific Function | Example Applications in Design Research |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Scanner | Measures blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals reflecting neural activity | Identifying brain regions engaged during conceptual design versus evaluation [2] |

| EEG System | Records electrical activity from scalp using electrode array | Differentiating cognitive processes between expert and novice designers [2] [1] |

| fNIRS System | Measures cortical blood flow using near-infrared light | Detecting prefrontal cortex changes during constrained versus open-ended design [2] |

| Eye Tracker | Records gaze patterns and pupillometry | Studying visual attention during design sketching and prototyping [1] |

| EDA Sensor | Measures skin conductance reflecting sympathetic arousal | Correlating emotional arousal with creative insight moments during designing [1] |

| HRV Monitor | Records heart rate variability indicating autonomic nervous system engagement | Assessing cognitive load and stress during different design phases [1] |

| Protocol Analysis Software | Facilitates transcription and coding of verbal data | Analyzing design reasoning patterns and strategy use [1] |

Visualization Framework and Data Representation

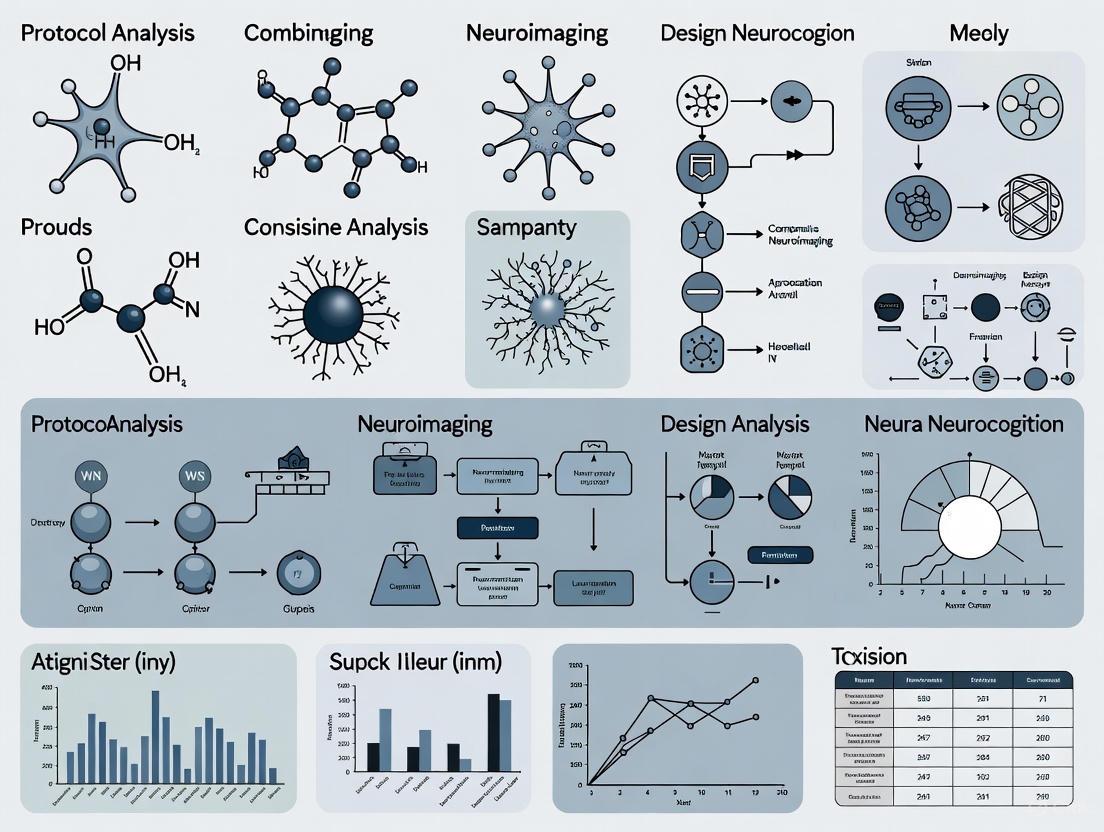

Triangulation Research Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for triangulation research in design neurocognition, illustrating the parallel data collection and integrated analysis framework.

Cognitive-Physiological-Neural Correlation Framework

Diagram 2: Correlation framework illustrating how different measurement modalities capture complementary aspects of design thinking processes.

The triangulation framework represents a methodological paradigm shift in design neurocognition research, offering unprecedented opportunities to investigate the complex interplay between cognitive, physiological, and neural systems during design thinking. By simultaneously capturing data from the mind, body, and brain, researchers can develop more comprehensive models of design cognition that account for its embodied, situated, and dynamic nature. The experimental protocols and application notes presented here provide a practical foundation for implementing this approach in research settings, while the visualization frameworks offer guidance for representing the complex, multi-modal data generated by these studies.

The potential applications of this framework extend beyond basic research to include design education, professional practice, and clinical interventions. In educational contexts, triangulation methods can identify the neurocognitive correlates of developing design expertise, informing pedagogical approaches that scaffold effective cognitive strategies [2] [1]. In professional practice, physiological and neurocognitive measures could provide real-time feedback on design cognition, potentially enhancing creativity and problem-solving effectiveness. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning approaches with multi-modal data holds promise for developing predictive models of design cognition that could transform how we understand, support, and enhance human creativity [3].

As neuroimaging technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, the triangulation framework will likely evolve to incorporate new measurement modalities and analytical approaches. The ongoing challenge for researchers will be to maintain the ecological validity of design studies while leveraging the increasingly sophisticated tools available for capturing cognitive, physiological, and neural processes. By embracing this multi-level, integrative approach, the field of design neurocognition can move toward a more complete understanding of one of humanity's most complex and valuable cognitive achievements: the capacity to design.

The Evolution from Behavioral Analysis to Neurophysiological Measurement

The field of design neurocognition has undergone a significant methodological evolution, transitioning from traditional behavioral observation to sophisticated neurophysiological measurement. This shift represents a fundamental change in how researchers understand and investigate the cognitive processes underlying design thinking. Where early research relied primarily on protocol analysis and behavioral observations, current approaches increasingly integrate multimodal neuroimaging techniques to capture the dynamic, in vivo neural correlates of creative design processes [4]. This evolution has enabled researchers to move beyond descriptive accounts of design behavior to identify the specific neurocognitive mechanisms that enable complex design thinking [4].

The integration of protocol analysis with neuroimaging represents a particularly powerful framework for design neurocognition research. By simultaneously capturing designers' verbalized thoughts and corresponding neural activity, researchers can establish meaningful connections between subjective cognitive experiences and objective physiological measures [4]. This combined approach addresses limitations inherent in either method alone, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how designers conceive, develop, and refine ideas through complex cognitive acts that intentionally generate new ways to change the world [4].

Comparative Analysis of Research Methods

The transition from behavioral to neurophysiological methods has expanded the toolkit available to design researchers, each approach offering distinct advantages and limitations for investigating design cognition.

Table 1: Comparison of Research Methods in Design Neurocognition

| Method Type | Specific Techniques | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Ecological Validity | Primary Applications in Design Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Analysis | Protocol analysis, think-aloud methods, video observation | N/A | Moderate | High | Identifying design strategies, problem-solving approaches, cognitive processes [4] |

| Functional Neuroimaging | fMRI, fNIRS | High (fMRI), Moderate (fNIRS) | Low (fMRI), Moderate (fNIRS) | Low (fMRI), High (fNIRS) | Localizing neural activity during design tasks, identifying brain networks [4] |

| Electrophysiological Recording | EEG, ERP | Low | High | Moderate | Tracking rapid changes in brain states during design process, measuring cognitive engagement [4] [5] |

| Multimodal Approaches | EEG + fNIRS, EEG + eye-tracking | Variable | Variable | High | Comprehensive assessment of cognitive and affective states during design [5] |

The choice of methodology involves significant trade-offs. Traditional behavioral methods like protocol analysis have provided rich descriptive accounts of design cognition but offer limited insight into the underlying neural mechanisms [4]. Conversely, neuroimaging techniques like fMRI provide excellent spatial resolution for localizing brain activity but constrain natural movement and lack the temporal resolution to capture rapid design cognition processes [4]. This limitation has driven the adoption of methods like EEG and fNIRS that offer better compatibility with ecologically valid design tasks while still providing objective physiological data [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Neurophysiological Metrics in Design Research

| Neurophysiological Metric | Calculation Method | Cognitive Correlate | Typical Values in Design Tasks | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Workload | Frontal Theta GFP / Parietal Alpha GFP [5] | Cognitive demand, processing intensity | Higher values indicate increased cognitive load | Values significantly above baseline suggest excessive cognitive demand |

| Attention/Concentration | Frontal Beta GFP / Frontal Theta GFP [5] | Focused attention, engagement | AIGC tools: M=51.06, SD=2.54; Traditional: M=48.31, SD=2.87 [6] | Higher values indicate greater attentional focus |

| Cognitive Engagement | Parietal Beta GFP / (Parietal Theta GFP + Parietal Alpha GFP) [5] | Active cognitive processing | Correlates with creative performance (r=0.67) [6] | Higher values associated with better creative outcomes |

| Relaxation Level | Alpha power asymmetry, heart rate variability | Stress reduction, cognitive flexibility | No significant difference between AIGC and traditional tools [6] | Moderate levels may facilitate creative insight |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Multimodal Assessment of Learning Materials

Objective: To investigate how different educational contents affect cognitive processing and engagement using simultaneous EEG, EDA, and PPG recording [5].

Participants: 10 volunteers (age range: 24-37 years, M=28.6, SD=4.56) recruited from university populations without financial compensation [5].

Materials and Setup:

- Mindtooth Touch EEG wearable system with 8 channels (AFz, AF3, AF4, AF7, AF8, Pz, P3, P4) sampled at 125Hz [5]

- Electrodermal activity (EDA) and photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors

- Computer monitor for stimulus presentation and external speakers for audio delivery

- Three educational contents about Bluetooth technology: (1) Educational video (6:49 minutes) with infographics and practical examples; (2) Academic video (7:17 minutes) with PowerPoint slides and voice-over; (3) Encyclopedic text (approximately 7 minutes reading time) [5]

Procedure:

- Obtain written informed consent and explain study procedures

- Record 60-second resting-state baseline at workstation

- Present three educational contents in randomized order to counterbalance order effects

- Record neurophysiological data continuously during each task

- Administer post-task questionnaires assessing cognitive effort and engagement

- Conduct comprehensive debriefing session [5]

Data Processing:

- Band-pass filter EEG signal (2-30 Hz) using 5th-order Butterworth filter

- Detect and correct eye blink artifacts using o-CLEAN method

- Remove EEG epochs with signal amplitude exceeding ±80 μV

- Compute Global Field Power (GFP) for Theta, Alpha, and Beta bands relative to Individual Alpha Frequency (IAF)

- Calculate mental workload, attention, and engagement indices using formulas specified in Table 2 [5]

Protocol 2: Assessing AIGC Impact on Design Creativity

Objective: To evaluate the effects of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content tools on creative performance and neurophysiological states in product design education [6].

Participants: 64 third-year undergraduate design students from a public university in Eastern China, randomly assigned to experimental (AIGC tools) or control (traditional software) conditions [6].

Materials and Setup:

- BrainLink Pro EEG headband devices for neurophysiological monitoring

- AIGC condition: ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion

- Control condition: Traditional design software

- Intelligent walking cane design task (3-hour duration)

- Standardized design assessment criteria for evaluating creative performance [6]

Procedure:

- Random assignment to AIGC or control group

- Explain intelligent walking cane design task requirements

- Apply EEG headsets and ensure proper signal acquisition

- Commence 3-hour design task with appropriate tool access

- Record EEG data continuously throughout design process

- Administer creative performance evaluation using standardized criteria

- Analyze concentration and relaxation levels from EEG data [6]

Creative Performance Assessment:

- Evaluate novelty, practicality, and aesthetic appeal of designs

- Use standardized rubrics with expert evaluators

- Compare scores between AIGC (M=115.13, SD=6.44) and traditional methods (M=110.69, SD=9.37) [6]

Data Analysis:

- Independent samples t-tests to compare group differences

- Pearson correlations to examine relationships between neurophysiological states and creative performance

- Effect size calculations using Cohen's d [6]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Design Neurocognition Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Equipment | Technical Specifications | Primary Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Systems | Mindtooth Touch EEG [5] | 8 channels (AFz, AF3, AF4, AF7, AF8, Pz, P3, P4), 125Hz sampling | Records electrical brain activity during design tasks | Balance between spatial coverage and practicality in naturalistic settings |

| EEG Systems | BrainLink Pro EEG Headband [6] | Wearable form factor, wireless operation | Monitors concentration and relaxation levels in educational settings | Suitable for extended design sessions with minimal discomfort |

| AIGC Tools | Midjourney, Stable Diffusion [6] | Image generation from text prompts, rapid iteration | Provides visual inspiration and design alternatives | May influence cognitive processes differently than traditional methods |

| AIGC Tools | ChatGPT [6] | Natural language processing, conversational interface | Generates design concepts and descriptive content | Potential impact on original thinking requires careful study design |

| Complementary Measures | EDA/PPG Sensors [5] | Electrodermal activity, cardiovascular monitoring | Captures autonomic nervous system responses during design | Provides affective and cognitive load data alongside EEG |

| Stimulus Presentation | Computerized Testing Systems | Precision timing, standardized administration | Presents design tasks in consistent manner | Critical for experimental control in neuroimaging studies |

Data Presentation and Visualization Standards

Effective presentation of quantitative data is essential for communicating research findings in design neurocognition. Structured tables should include clear titles, column headings, and appropriate organization of data to facilitate comparison across experimental conditions [7] [8]. When presenting frequency distributions for quantitative data, histograms provide superior representation compared to standard bar charts because they properly represent the continuous nature of numerical data along the horizontal axis [9].

For time-series data or comparative studies, frequency polygons offer advantages in visualizing distributions and trends across multiple conditions [9]. These graphical representations are particularly valuable for showing how reaction times or cognitive engagement metrics differ between experimental groups, such as when comparing AIGC-assisted design versus traditional methods [6] [9].

When creating visualizations, researchers must adhere to accessibility guidelines including sufficient color contrast ratios—at least 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text against background colors [10]. This ensures that diagrams and data presentations are readable by all audiences, including those with visual impairments. The selection of color palettes should follow established principles like the 60-30-10 rule (60% primary color, 30% secondary color, 10% accent color) to create visually harmonious and effective scientific communications [11] [12].

The evolution from behavioral analysis to neurophysiological measurement represents a paradigm shift in design neurocognition research. By integrating protocol analysis with advanced neuroimaging techniques, researchers can now investigate design thinking through multiple complementary lenses, capturing both the subjective experience and objective neural correlates of creative cognition [4]. The experimental protocols outlined herein provide methodological frameworks for conducting rigorous studies that advance our understanding of how designers think, create, and innovate.

Future research directions should focus on further refining multimodal approaches that combine the temporal resolution of EEG with the spatial precision of fNIRS or fMRI, particularly as these technologies become more accessible and suitable for naturalistic design environments [4] [5]. Additionally, as AIGC tools become increasingly sophisticated, understanding their impact on neurocognitive processes during design will be essential for effectively integrating these technologies into design education and practice [6]. Through continued methodological innovation and rigorous application of neurophysiological measures, the field of design neurocognition will further illuminate the complex brain mechanisms that enable humans to imagine and create novel solutions to complex problems.

Design cognition represents one of the most complex facets of human intelligence, encompassing problem-solving, creativity, and the dynamic interplay between problem definition and solution development. This article frames these core processes within an emerging research paradigm that integrates traditional protocol analysis with modern cognitive neuroscience methodologies [4]. The integration of these approaches provides a multi-level analytical framework for investigating the neurocognitive systems underlying design thinking, offering unprecedented insights into the mental processes that enable designers to conceive and develop novel ideas [4]. This synthesis of behavioral and neural data holds strong potential to generate powerful datasets that can discriminate among competing theoretical propositions about the design process, ultimately impacting design theory, education, and professional practice [4].

Core Theoretical Foundations

Problem-Solving in Design

Design problem-solving deviates significantly from traditional problem-solving approaches. Whereas conventional problem solving often follows a structured, systematic process, design cognition exhibits substantial opportunistic behaviors and frequent deviations from predefined methods [13]. Protocol analysis studies have revealed that designers engage in significant deviations from structured processes, demonstrating cognitive behaviors that are highly adaptive and responsive to emerging insights during the design process [13]. This opportunistic nature of design thinking represents a fundamental characteristic that distinguishes it from other forms of problem solving.

Neuroimaging evidence supports this distinction, revealing distinct patterns of prefrontal cortex activity between design tasks and traditional problem-solving tasks [4]. These neural differences underscore the unique cognitive demands of design problem-solving, which involves navigating ambiguity, managing conflicting constraints, and generating novel solutions in contexts where problem parameters may be initially ill-defined.

Creativity and Idea Generation

Creative cognition in design involves complex neural systems that support idea generation, evaluation, and refinement. Neuroscience investigations have revealed that inspirational stimuli promote idea generation while eliciting distinct patterns of brain activation compared to trials without such stimuli [4]. This neural evidence provides insights into the cognitive mechanisms underlying creative inspiration and its role in facilitating the generative aspects of design thinking.

The process of creativity in design also involves distinguishable neural patterns between generating ideas and evaluating them. Studies examining designers alternating between creating comic book covers and evaluating their designs have demonstrated dissociable brain activation patterns between these distinct creative phases [4]. This neural differentiation highlights the multifaceted nature of creative cognition in design, which encompasses both generative and evaluative processes that engage partially distinct neurocognitive systems.

Co-evolution of Problem and Solution Spaces

The co-evolution model represents a foundational framework in design cognition, describing the iterative, reflective process where problem understanding and solution development evolve synergistically. Protocol analysis studies involving creative design evaluations have demonstrated that insight-driven problem reframing is crucial to the creative design process, supporting Schön's conceptualization of design as a reflective conversation with the materials of a problem situation [13].

This co-evolutionary process involves continuous refinement of both the problem space and solution space through iterative cycles of reflection and adaptation. Designers engage in a dynamic process where emerging solutions reshape problem understanding, which in turn informs further solution development. This recursive interaction represents a cornerstone of creative design cognition that differentiates it from more linear problem-solving approaches.

Methodological Integration: Protocol Analysis and Neuroimaging

Protocol Analysis Methods

Protocol analysis provides a robust empirical methodology for studying the cognitive behaviors and thought processes employed by designers during problem-solving activities [13]. This approach aims to collect detailed data about the problem-solving process, analyze this information, and reconstruct the cognitive events occurring within the designer's mind.

Table 1: Protocol Analysis Data Collection Approaches

| Method Type | Procedure | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent Protocol | Problem solver verbalizes thoughts while working on tasks; session is recorded and transcribed [13] | Reveals sequence of cognitive events from short-term memory; provides rich details of the design process [13] | May interfere with natural cognitive process; may yield incomplete protocols [13] | Studying real-time cognitive processes; analyzing information processing sequences [13] |

| Retrospective Protocol | Interviews conducted after task completion; problem solver recalls activities; session recorded and transcribed [13] | Less intrusive to the design process itself [13] | May produce incomplete or rationalized accounts due to memory limitations [13] | Examining design outcomes; understanding design rationale [13] |

The validity of protocol analysis rests on two fundamental assumptions. First, the design process exhibits conversational characteristics, operating as either an internal monologue or external conversations between designers. Second, verbalizing thoughts during problem-solving does not significantly alter the structure of the cognitive processes involved [13]. While some researchers have expressed concerns about potential interference, the prevailing view acknowledges that concurrent protocols provide valuable insights into cognitive events and information processing in short-term memory.

Table 2: Protocol Data Analysis Approaches

| Analysis Method | Segmentation Basis | Analytical Focus | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process-Oriented Segmentation | Changes in problem-solving intentions or activities using syntactic markers or predefined taxonomies [13] | Sequence of problem-solving activities and design moves [13] | Reconstructs design process sequence; identifies correlations between design intentions [13] | Fails to examine what designers see and think and what knowledge they exploit [13] |

| Content-Oriented Segmentation | Visual and non-visual cognitive contents using classification schemes (physical, perceptual, functional, conceptual) [13] | Cognitive interaction between designer and artifacts; what designers see, think, and know [13] | Examines cognitive interactions with artifacts; reveals how sketches serve as external memory [13] | Less focused on process sequence and correlation between activities [13] |

Cognitive Neuroscience Methods

Cognitive neuroscience methodologies provide complementary approaches for investigating the neural mechanisms underlying design thinking, offering insights into the brain systems that support complex design cognition.

Table 3: Neuroimaging Techniques in Design Neurocognition Research

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications in Design Research | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) | High (localization of brain activity) [4] | Low (measures slow hemodynamic response) [4] | Identifying neural differences between designing and problem-solving; evaluating impact of inspirational stimuli [4] | Expensive; restrictive environment; motion artifacts during design tasks [4] |

| EEG/ERP (Electroencephalography/Event-Related Potentials) | Low (poor localization of source activity) [4] | High (millisecond precision) [4] | Distinguishing cognitive processes via alpha-band activity; measuring effort, fatigue, and concentration [4] | Sensitive to motion artifacts; challenging to pair with verbal protocols [4] |

| fNIRS (Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy) | Moderate (inferior to fMRI) [4] | Moderate | Detecting cortical shifts from design constraints; differentiating expert strategies in naturalistic settings [4] | Allows free movement, speaking, and device use; suitable for real-world settings [4] |

Neuroscience studies have revealed that designing engages distinct neural patterns compared to other forms of cognition. Early fMRI investigations found differential engagement of prefrontal cortex during design tasks compared to problem-solving tasks [4]. EEG studies have demonstrated that specific frequency bands, particularly alpha activity over temporal and occipital regions, can distinguish between different types of problem descriptions during design problem-solving [4]. Furthermore, neuroimaging evidence suggests that different forms of design expertise are reflected in distinguishable patterns of brain activity, with mechanical engineers showing different activation patterns compared to industrial designers [4].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Multi-Method Research Protocol

Figure 1: Integrated research protocol workflow combining behavioral and neuroimaging methods.

Comprehensive Experimental Protocol

Title: Investigating Co-evolution in Design Thinking Using Concurrent Protocol Analysis and Functional Neuroimaging

Objective: To examine the neural correlates and cognitive processes underlying problem-solution co-evolution during conceptual design tasks.

Participants:

- Target N = 20-30 professional designers or advanced design students

- Balanced for design domain expertise (e.g., industrial design, engineering design, architecture)

- Screening for normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological disorders

Materials and Equipment:

- Design Problem Sets: Three ill-structured design problems of equivalent complexity

- Protocol Recording System: High-quality audio/video recording equipment

- Sketching Materials: Digital tablet with stylus or paper-based sketching materials

- Neuroimaging Apparatus: fNIRS headset or EEG cap with appropriate channel configuration

- Data Synchronization System: Time-synchronization software for multi-modal data integration

Procedure: 1. Participant Preparation (30 minutes): - Obtain informed consent - Apply neuroimaging sensors (fNIRS/EEG) - Conduct thinking-aloud training session with practice tasks

- Experimental Session (90 minutes):

- Present design problems in counterbalanced order

- Record concurrent verbal protocols during task execution

- Collect neuroimaging data throughout design process

- Document all sketches and external representations produced

- Post-Task Procedures (30 minutes):

- Conduct retrospective interviews using video-cued recall

- Administer post-experiment questionnaires on design strategies and task perceptions

Data Analysis Plan: 1. Protocol Analysis: - Transcribe verbal protocols verbatim - Segment protocols using both process-oriented and content-oriented approaches - Code for design moves, cognitive activities, and problem-solution transitions

- Neuroimaging Analysis:

- Preprocess neural data to remove artifacts

- Extract task-related neural activity changes

- Identify neural correlates of key design cognitive events

- Integrative Analysis:

- Synchronize protocol codes with neural activity patterns

- Conduct cross-correlation analysis between cognitive and neural events

- Identify neural signatures of co-evolutionary design processes

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Design Neurocognition Studies

| Material Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Collection Tools | Digital audio recorder, video recording system, screen capture software | Capturing verbalizations, gestures, and design actions | Minimum 48kHz audio sampling; 1080p video resolution; time-synchronization capability |

| Neuroimaging Equipment | fNIRS headset, EEG system, fMRI scanner | Measuring brain activity during design tasks | fNIRS: 16+ sources, 16+ detectors; EEG: 32+ channels; fMRI: 3T+ magnetic field strength |

| Design Task Materials | Problem briefs, inspirational stimuli, design constraints | Eliciting authentic design cognition | Ecologically valid problems; professionally relevant constraints; adjustable complexity |

| Data Analysis Software | Protocol transcription software, statistical packages, neuroimaging analysis tools | Processing and analyzing multi-modal data | NLP capabilities for protocol analysis; SPM, FSL, or equivalent for neuroimaging data |

| Behavioral Coding Systems | Coding scheme manuals, reliability assessment tools | Standardizing qualitative data analysis | Explicit code definitions; inter-rater reliability >0.8; comprehensive coding guidelines |

Integrated Analytical Framework

The powerful integration of protocol analysis and neuroimaging enables researchers to triangulate findings across multiple levels of analysis, connecting rich behavioral data with underlying neural mechanisms. This multi-method approach allows for investigating how specific cognitive processes identified in verbal protocols correspond with patterns of brain activation, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of design neurocognition.

This integrated framework supports the examination of complex research questions regarding the neural basis of design expertise, the cognitive effects of different design tools and methods, and the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying creative breakthroughs in design. By combining the temporal depth of protocol analysis with the physiological specificity of neuroimaging, researchers can develop more nuanced models of design thinking that account for both behavioral manifestations and neural implementations of core cognitive processes in design.

Future advancements in this interdisciplinary field will likely include more sophisticated data fusion techniques, improved ecological validity through portable neuroimaging technologies, and the development of comprehensive theoretical models that bridge the cognitive and neural levels of analysis in design thinking.

In the field of design neurocognition, understanding the brain's response to design elements requires capturing a comprehensive picture of neural activity, which no single imaging modality can fully provide. The four key non-invasive neuroimaging techniques—functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), Electroencephalography (EEG), and Magnetoencephalography (MEG)—each offer unique windows into brain function through different biophysical signals [14]. fMRI and fNIRS measure hemodynamic responses, the indirect, slow consequences of neural activity related to blood flow and oxygenation [15] [14]. In contrast, EEG and MEG directly capture the fast electrophysiological activity of neuronal populations [15] [16]. The integration of these complementary modalities, a approach known as multimodal neuroimaging, is crucial for bridging the gap between the brain's rapid electrical events and the slower, metabolically coupled hemodynamic changes, thereby offering a more complete understanding of the neural underpinnings of design perception and cognition [15] [14] [16]. This protocol outlines the application, advantages, and limitations of each modality, with a specific focus on their relevance to experimental design in neurocognitive studies of design.

Physiological Origins and Technical Principles

- EEG: EEG measures the electrical potentials generated by the synchronized postsynaptic activity of large groups of pyramidal neurons in the cortex. These signals are detected via electrodes placed on the scalp [15] [16]. Its exceptional temporal resolution (milliseconds) allows for the real-time tracking of brain dynamics, making it ideal for studying rapid cognitive processes engaged by design stimuli [15].

- MEG: MEG detects the minute magnetic fields produced by intracellular electrical currents within neurons. Like EEG, it offers millisecond temporal resolution but is less distorted by the skull and scalp, granting it superior spatial resolution for source localization [15] [14].

- fMRI: fMRI indirectly measures neural activity by detecting changes in blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast. Active brain regions experience a hemodynamic response, increasing oxygenated blood flow, which alters the local magnetic properties detectable by an MRI scanner [14]. It provides high spatial resolution (millimeters) and excellent whole-brain coverage, including deep structures [15].

- fNIRS: fNIRS is an optical imaging technique that measures cortical hemodynamic activity by shining near-infrared light through the scalp and detecting its attenuation after passing through brain tissue. Using the modified Beer-Lambert law, it calculates changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations, providing a hemodynamic correlate of neural activity similar to fMRI [15] [16].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Neuroimaging Modalities

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Measured Signal | Key Advantages | Primary Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | High (Milliseconds) [15] | Low (Centimeters) [15] | Electrical potentials from postsynaptic neurons [15] [16] | Direct neural measure, portable, low cost, non-invasive [15] | Low spatial resolution, sensitive to artifacts, limited to cortical surface [15] |

| MEG | High (Milliseconds) [15] | Medium (Millimeters to Centimeters) [15] [14] | Magnetic fields from intracellular currents [14] | High temporal resolution, less signal distortion from skull than EEG [15] | Very high cost, limited to specialized shielded rooms, insensitive to deep sources [15] |

| fNIRS | Low (Seconds) [15] | Medium (Centimeters) [15] | Hemodynamic (HbO/HbR concentration) [15] [16] | Portable, allows natural movement, resistant to motion artifacts [15] [16] | Limited depth penetration, sensitive to scalp hemodynamics, low temporal resolution [15] |

| fMRI | Low (Seconds) [15] | High (Millimeters) [15] | Hemodynamic (BOLD signal) [14] | High spatial resolution, whole-brain coverage, can study deep structures [15] | Low temporal resolution, expensive, non-portable, noisy environment [15] |

Relevance to Design Task Research

The choice of neuroimaging modality is dictated by the specific research question in design neurocognition.

- Investigating Rapid Visual Perception and Aesthetic Judgement: The high temporal resolution of EEG and MEG is critical for dissecting the rapid, sequential stages of visual processing when a participant first views a design. These modalities can track the timing of pre-attentive processing, engagement of attention, and the emergence of an aesthetic preference with millisecond precision [15].

- Mapping Sustained Attention and Cognitive Workload during Design Tasks: fNIRS and fMRI are well-suited for studies where participants engage in prolonged tasks, such as evaluating a complex user interface or solving a design problem. Their good spatial resolution allows researchers to map the sustained activation in networks associated with attention (e.g., frontoparietal network) and cognitive load (e.g., prefrontal cortex) [15] [17].

- Studying Brain Network Dynamics and Connectivity: Understanding how different brain regions communicate during creative design or problem-solving requires analyzing functional connectivity. fMRI provides the whole-brain coverage needed to map large-scale networks. EEG and MEG can track the fast oscillatory dynamics and phase synchronization that underlie network communication, while combined fNIRS-EEG offers a portable solution for studying network coupling in real-world settings [17] [18].

- Ecological Validity and Naturalistic Settings: When the experimental goal is to study brain activity in realistic environments (e.g., while using a prototype, in a virtual reality simulation, or even walking), the portability of EEG and fNIRS is a decisive advantage [16]. These modalities are more tolerant of movement than fMRI and MEG, allowing for more natural participant behavior.

Experimental Protocols for Design Neurocognition

Protocol 1: fNIRS-EEG for Motor Imagery Task

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating structure-function relationships using simultaneous EEG and fNIRS during a motor imagery task, relevant for assessing brain-computer interfaces or embodied design cognition [17].

Objective: To characterize the coupling between electrical and hemodynamic brain activity during motor imagery and its relationship to the underlying structural connectome.

Materials and Reagents:

- Integrated fNIRS-EEG System: A simultaneous recording setup with synchronized data acquisition [17].

- fNIRS Components: Sources (lasers/LEDs at 760 nm & 850 nm), detectors, and optodes arranged in a cap with an inter-optode distance of 30 mm [17].

- EEG System: 30+ electrodes configured according to the international 10-5 or 10-20 system [17].

- Stimulus Presentation Software: For displaying motor imagery cues (e.g., arrows for left/right hand).

- Data Processing Tools: MNE-Python, Brainstorm, Homer2, or similar toolboxes for data analysis [17].

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Seat the participant comfortably. Measure head size and fit the integrated fNIRS-EEG cap, ensuring proper optode and electrode contact. For fNIRS, verify signal quality using the scalp-coupled index (SCI); exclude channels with SCI < 0.7 [17].

- Experimental Paradigm:

- Resting-State Baseline (5 minutes): Record brain activity while the participant rests with eyes open or closed [17].

- Task Block: Present a visual cue (e.g., an arrow) indicating "left hand" or "right hand" motor imagery. Each trial lasts 10 seconds, followed by a random inter-trial interval. Conduct 30+ trials per condition [17].

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record EEG data at a sampling rate ≥ 200 Hz and fNIRS data at a sampling rate ≥ 10 Hz [17].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Data Analysis:

- Extract task-related features: Event-Related Desynchronization/Synchronization (ERD/ERS) from EEG, and HbO/HbR concentration changes from fNIRS.

- Perform source localization on both EEG and fNIRS data.

- Calculate functional connectivity and use graph signal processing to compute the Structural-Decoupling Index (SDI) to quantify structure-function relationships [17].

Protocol 2: EEG Analysis for Stroke Motor Recovery

This protocol, derived from clinical studies, outlines quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis to predict motor recovery. It serves as a model for using EEG to track neuroplastic changes and functional recovery, which can be analogous to measuring cognitive "recovery" or adaptation in usability testing [18].

Objective: To identify qEEG biomarkers, such as the Power Ratio Index (PRI) and Brain Symmetry Index (BSI), that correlate with and predict motor function recovery.

Materials and Reagents:

- EEG System: Clinical-grade EEG amplifier and electrode cap with at least 19 electrodes.

- Electrode Gel/Saline Solution: To ensure good electrical impedance (< 5 kΩ).

- Clinical Assessment Scales: Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) for validation [18].

Procedure:

- Participant Setup: Apply the EEG cap according to the international 10-20 system. Ensure impedances are low and stable.

- Data Recording: Record resting-state EEG for at least 5 minutes with eyes closed. Optionally, record during simple motor tasks.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Filter raw EEG data (e.g., 0.5-70 Hz).

- Manually or automatically identify and remove segments with major artifacts.

- Segment data into clean, artifact-free epochs.

- Quantitative EEG Analysis:

- Power Spectral Density (PSD): Compute PSD for standard frequency bands (Delta: 0.5-4 Hz, Theta: 4-7 Hz, Alpha: 8-12 Hz, Beta: 13-30 Hz) [18].

- Power Ratio Index (PRI): Calculate PRI as (Delta + Theta Power) / (Alpha + Beta Power). A higher PRI indicates poorer outcome [18].

- Brain Symmetry Index (BSI): Calculate BSI by comparing the power spectra between homologous hemispheres. A value closer to 1 indicates greater asymmetry and poorer prognosis [18].

- Correlation with Behavior: Statistically correlate qEEG parameters (PRI, BSI) with clinical motor scores (e.g., FMA) to establish their predictive validity [18].

Figure 1: A workflow for quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis to derive biomarkers for functional recovery prediction, based on established clinical protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Featured Neuroimaging Experiments

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated fNIRS-EEG Cap | A headgear integrating optical fNIRS optodes and electrical EEG electrodes for simultaneous hemodynamic and electrical data acquisition [17]. | Core component for the simultaneous fNIRS-EEG motor imagery protocol [17]. |

| MR-Compatible EEG System | Specially designed EEG equipment (electrodes, amplifiers, cables) that is safe and functional inside the MRI scanner, minimizing interference and artifact [15]. | Essential for concurrent EEG-fMRI studies, not detailed here but a key multimodal tool. |

| Optical Sources & Detectors | fNIRS system components; sources emit near-infrared light, detectors measure light intensity after tissue passage [16] [17]. | Required for fNIRS measurement in the fNIRS-EEG protocol. |

| Electrode Conductive Gel | A saline-based gel applied to EEG electrodes to reduce impedance between the scalp and electrode, ensuring high-quality signal acquisition. | Used in both EEG-specific and combined protocols during participant setup. |

| Structural MRI Template | A high-resolution anatomical brain image (e.g., MNI template) used for co-registration and source localization of EEG/fNIRS data [17]. | Used to map functional activity onto brain anatomy in the fNIRS-EEG protocol. |

| Graph Signal Processing (GSP) Tools | Computational framework using mathematical graph theory to analyze the relationship between structural and functional brain networks [17]. | Used to compute the Structural-Decoupling Index (SDI) in the fNIRS-EEG protocol [17]. |

Integrated Data Analysis and Fusion Techniques

Multimodal neuroimaging's power is unlocked through sophisticated data fusion techniques, which can be categorized based on the level of integration.

- Parallel Analysis: Data from different modalities (e.g., EEG and fNIRS) are analyzed separately but then interpreted together to provide a complementary picture [16]. For example, the timing of an event-related potential (ERP) from EEG can be overlaid with the spatial location of activation from fNIRS.

- Asymmetric (Informed) Analysis: The data from one modality is used to constrain or inform the analysis of another [16]. For instance, fMRI-derived activation maps can be used as priors to improve the accuracy of EEG source localization.

- Symmetrical (Fully Fused) Analysis: Data from all modalities are combined into a single generative model that explains all data simultaneously. This is the most computationally complex approach but offers the most unified view of brain activity [14]. A novel method using Virtual Sensors (VS) combines EEG and MEG data to directly capture brain activity with improved accuracy and to identify trial-to-trial variability, bypassing the need for complex source modeling [15].

fMRI, fNIRS, EEG, and MEG each provide a unique and valuable perspective on brain function, with inherent trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, cost, and practicality. The future of design neurocognition lies not in identifying a single "best" modality, but in the principled combination of these tools to ask specific, well-defined research questions. By leveraging the high temporal resolution of EEG/MEG to capture the dynamics of design perception and the superior spatial mapping of fMRI/fNIRS to localize sustained cognitive processes, researchers can build a more holistic and mechanistic model of the brain's response to design. The protocols and analyses outlined here provide a foundation for developing rigorous, multimodal research programs that can ultimately bridge the gap between neural processes and design cognition.

The Role of Protocol Analysis in Capturing Verbalized Design Thinking

Protocol analysis is an empirical research method for studying the cognitive behaviors and thought processes of individuals as they engage in problem-solving and design tasks [13]. Within design neurocognition, it serves as a critical bridge between observable behaviors and the underlying neurocognitive mechanisms. The core premise is that having participants verbalize their thoughts provides a window into their cognitive process, which, when integrated with neuroimaging data, offers a multi-level understanding of design thinking [4] [13]. This approach is foundational for reconstructing the sequence of cognitive events—such as problem framing, idea generation, and solution evaluation—that constitute the complex, higher-order cognition of design [4] [13].

Core Methodologies: Data Collection and Analysis

The application of protocol analysis involves standardized procedures for data collection and segmentation to ensure valid and reliable insights into the design process.

2.1 Data Collection Protocols There are two primary approaches to gathering verbalized data, each with distinct advantages [13]:

- Concurrent Verbal Protocol (Think-Aloud): Participants are trained to verbalize their thoughts in real-time while working on a design task. The session is audio and/or video recorded for later transcription [13] [19].

- Retrospective Verbal Protocol: Participants are interviewed immediately after completing the design task and asked to recall their activities and thoughts. The interview is recorded and transcribed. To enhance accuracy, videotapes of the design session and the artifacts produced (e.g., sketches) are often used as memory cues [13].

2.2 Data Analysis and Segmentation The transcribed verbal data is coded into segments for analysis. Segmentation is typically based on a change in the problem solver’s intention or the content of their thoughts [13]. Two principal approaches guide this analysis:

- Process-Oriented Segmentation: This approach describes the design process as a sequence of problem-solving activities using a pre-defined taxonomy (e.g., problem recognition, goal setting, solution proposing, solution analysing). It is useful for identifying time spent on different design intentions and reconstructing their sequence and correlations [13].

- Content-Oriented Segmentation: This approach focuses on the cognition of the designer—what they see, think, and what knowledge they use. Segments are classified into categories such as:

- Physical: Depiction, looking, motion.

- Perceptual: Perceiving depicted elements and their relations.

- Functional: Assigning meaning to depictions.

- Conceptual: Goal setting and decision making [13].

Integration with Neuroimaging in Design Neurocognition

Protocol analysis provides the behavioral and cognitive context for interpreting neuroimaging data, creating a powerful synergistic framework for design neurocognition [4].

3.1 Multi-Modal Experimental Framework Neuroimaging techniques capture the neural correlates of the cognitive processes verbalized during protocol sessions. Key techniques include:

- Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): Offers high spatial resolution for localizing brain activity. Studies have shown distinct patterns of prefrontal cortex engagement during design tasks compared to standard problem-solving [4].

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Provides high temporal resolution to track the rapid evolution of neural processes during design. For example, higher alpha-band activity over temporal and occipital regions can distinguish between open-ended and closed-ended problem-solving [4].

- Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS): An emerging tool that allows for more naturalistic data collection as participants can freely move and speak, making it highly compatible with concurrent verbal protocol methods [4].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these methods in a typical experiment:

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols

4.1 Protocol: Investigating the Impact of Inspirational Stimuli on Concept Generation This protocol examines how different types of stimuli influence the brain networks and cognitive processes involved in creative idea generation [4].

- Objective: To identify neural and cognitive differences in conceptual design problem-solving with and without inspirational stimuli.

- Participants: Professional designers or individuals with relevant design experience.

- Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Design Problem Briefs | Standardized, open-ended tasks to initiate the design process. |

| Inspirational Stimuli | Visual or textual cues that are more or less related to the problem space, used to prompt idea generation [4]. |

| Audio/Video Recording System | Captures high-fidelity verbal protocols and behavioral data. |

| Neuroimaging System (fMRI/EEG/fNIRS) | Records neural activity during the design task. fMRI localizes brain activity, while EEG tracks its temporal dynamics [4]. |

| Data Coding Scheme (e.g., Content-Oriented) | A standardized framework for segmenting and categorizing verbal transcript data into cognitive categories [13]. |

- Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Obtain informed consent. Train participants in the think-aloud technique. Prepare the participant for the neuroimaging setup (e.g., positioning in the fMRI scanner, fitting the EEG cap).

- Task Execution: Participants are presented with a design problem in a block-based or event-related design.

- Condition A (With Stimuli): Participants generate ideas while being presented with inspirational stimuli.

- Condition B (Without Stimuli): Participants generate ideas without any inspirational stimuli.

- Data Acquisition: Participants verbalize their thoughts concurrently while neuroimaging data is collected continuously.

- Post-task Interview: Conduct a brief retrospective interview using the recorded session to clarify design rationales.

- Data Analysis:

- Verbal Data: Transcribe audio recordings. Code the transcripts using a content-oriented scheme (e.g., identifying physical, perceptual, functional, and conceptual segments) [13].

- Neuroimaging Data: Preprocess data (e.g., motion correction for fMRI, filtering for EEG). Analyze for condition-specific activation (fMRI) or spectral power changes (EEG) [4].

- Integration: Correlate the frequency or sequence of specific cognitive segments (e.g., "functional thought") with activation in corresponding brain networks (e.g., prefrontal cortex).

4.2 Protocol: Comparing Cognitive Strategies Across Expert Groups This protocol uses protocol analysis and neuroimaging to dissect differences in design thinking between experts from different fields.

- Objective: To identify how expertise shapes cognitive and neural processes during design problem-solving.

- Participants: Two distinct groups of experts (e.g., mechanical engineers vs. industrial designers) [4].

- Procedure:

- The experimental setup is similar to section 4.1.

- All participants complete the same set of design tasks while providing concurrent verbal protocols and undergoing neuroimaging (EEG is suitable for capturing rapid temporal dynamics associated with different strategies) [4].

- Verbal data is segmented using a process-oriented approach to categorize design moves and strategies [13].

- Expected Outcomes: Previous research indicates that different expert groups show distinct patterns of local brain activity and temporal distribution of that activity across prefrontal and occipitotemporal regions [4]. Verbal protocols may reveal different frequencies in the use of strategies like brainstorming or morphological analysis [4].

The logical relationship between experimental phases and data types is summarized below:

Data Presentation: Quantitative Summaries

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Protocol Analysis Data Collection Methods

| Parameter | Concurrent Protocol | Retrospective Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Definition | Real-time verbalization of thoughts during task execution [13]. | Recall and verbalization of thoughts after task completion, often cued by video [13]. |

| Intrusiveness | Can be intrusive and may interfere with the primary task for some individuals [13] [19]. | Considered less intrusive to the task process itself [13]. |

| Cognitive Source | Accesses information in Short-Term Memory (STM) [13]. | Relies on information retrieved from Long-Term Memory (LTM), which may be less detailed [13]. |

| Data Completeness | Provides a sequence of cognitive events from STM, but may be incomplete if verbalization lags [13]. | May produce a larger number of segments but can be a rationalized story rather than the actual sequence [13]. |

| Suitability | For examining the cognitive process as it unfolds [13]. | For examining outcomes and design rationale [13]. |

Table 2: Summary of Neuroimaging Techniques Paired with Protocol Analysis

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Compatibility with Protocol Analysis | Primary Application in Design Neurocognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | High | Low (seconds) | Low due to noise and restraint; better for retrospective analysis. | Localizing brain regions involved in design vs. problem-solving [4]. |

| EEG | Low | High (milliseconds) | Moderate; motion artifacts can be an issue during sketching. | Distinguishing cognitive processes (e.g., attention vs. association) via brain oscillations [4]. |

| fNIRS | Moderate | Moderate | High; participants can speak and move freely. | Detecting cortical shifts during real-world design tasks and team interactions [4]. |

A Methodological Guide: Combining Protocol Analysis with Neuroimaging in Practice

Synchronizing Verbal Protocols with Neuroimaging Data Streams

The integration of verbal protocol analysis with neuroimaging represents a paradigm shift in design neurocognition research, enabling unprecedented triangulation of cognitive processes. This approach captures the rich, explicit reasoning of designers through their verbal reports while simultaneously measuring implicit, objective neurophysiological correlates [1]. Such multimodal integration addresses fundamental challenges in studying design thinking, an activity characterized by complex, ill-defined problems and the co-evolution of problem-solution spaces [1]. This document provides comprehensive application notes and experimental protocols for successfully synchronizing these heterogeneous data streams, framed within the broader context of advancing design neurocognition methodology.

Theoretical Foundation and Significance

The Triangulation Framework in Design Neurocognition

Research in design thinking has evolved to encompass three complementary paradigmatic approaches: design cognition (measuring the mind through verbal protocols), design physiology (measuring the body through eye tracking, EDA, HRV), and design neurocognition (measuring the brain through EEG, fMRI, fNIRS) [1]. Each approach provides unique insights into different characteristics of design thinking, including design reasoning, creativity, fixation, and collaboration patterns.

Verbal protocol analysis allows researchers to study cognitive processes by analyzing participants' verbal utterances during controlled experiments or in-situ designing [1]. When synchronized with neuroimaging data streams, it becomes possible to correlate specific cognitive states identified in verbal reports with their underlying neural signatures, creating a more complete picture of the neurocognitive basis of design.

Key Advantages of Synchronized Data Streams

Synchronizing verbal protocols with neuroimaging addresses several limitations of single-method approaches. It helps overcome the subjectivity and potential recall inaccuracies of self-reports by providing objective physiological correlates [1]. Additionally, it enables researchers to capture rapid, implicit cognitive processes that may not be verbally reported but are detectable in neuroimaging signals. The method also provides temporal precision for linking specific design events in the verbal protocol with concurrent brain activity patterns, and offers multimodal validation where converging evidence from different measurement modalities strengthens research findings.

Neuroimaging Modalities: Technical Specifications and Applications

Different neuroimaging techniques offer distinct advantages for design neurocognition research, varying in temporal resolution, spatial resolution, practicality, and compatibility with verbal protocol collection.

Table 1: Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities for Design Neurocognition Research

| Modality | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Portability/ Compatibility with Verbalizing | Primary Applications in Design Thinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | ~1-2 seconds (slow) | 1-3 mm (high) | Low; significant scanner noise interferes with verbalization | Brain mapping of sustained design states, structural-functional relationships [20] [1] |

| EEG | <1 millisecond (very high) | ~10 mm (low) | High; portable systems allow natural design settings | Tracking rapid cognitive shifts, attention, engagement during design tasks [21] [1] |

| fNIRS | ~1 second (moderate) | 10-20 mm (low-moderate) | High; tolerant of movement, quiet operation | Studying realistic design activities, collaborative design, classroom studies [1] |

| MEG | <1 millisecond (very high) | 2-3 mm (high) | Low; requires specialized shielded room | Mapping neural dynamics of insight, creativity, and problem-solving [22] |

The selection of an appropriate neuroimaging modality depends on the specific research questions, with fMRI offering superior spatial localization for pinpointing brain regions involved in design cognition, while EEG provides millisecond-level temporal resolution to capture rapid cognitive transitions during design thinking processes [20] [21]. fNIRS offers a practical balance for studying designers in more ecologically valid environments [1].

Integrated Experimental Protocol: Synchronizing Verbal Protocols with fNIRS

This section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol for a representative experiment investigating neural correlates of design fixation using synchronized verbal protocols and fNIRS.

Pre-Experimental Preparation

Materials and Equipment:

- fNIRS system with appropriate number of channels (≥20 recommended)

- Recording equipment for verbal protocols (high-quality audio recorder)

- Stimulus presentation computer and software

- Design task materials (problem statements, example solutions)

- Data synchronization unit (e.g., Lab Streaming Layer LSL)

- Comfortable seating and work surface for participant

Participant Preparation:

- Obtain informed consent following institutional ethics guidelines.

- Prepare fNIRS optodes according to the 10-20 international system, focusing on prefrontal and parietal regions implicated in design cognition.

- Verify signal quality from all channels before proceeding.

- Provide clear instructions about the think-aloud protocol, emphasizing continuous verbalization without self-censorship.

Experimental Procedure

- Baseline Recording (5 minutes): Collect resting-state fNIRS data with eyes open while participant remains silent.

- Practice Session (5 minutes): Administer a simple design task (e.g., "design a simple bookmark") to acclimate participant to thinking aloud while fNIRS data is collected.