Mapping Shared Brain Substrates Across Behavioral Domains: From Foundational Networks to Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes current research on the shared neural architectures that underpin multiple behavioral domains, including cognition, personality, and mental health.

Mapping Shared Brain Substrates Across Behavioral Domains: From Foundational Networks to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the shared neural architectures that underpin multiple behavioral domains, including cognition, personality, and mental health. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational brain networks identified through lesion-behavior mapping and functional connectivity studies. The review delves into advanced methodological approaches for deriving robust brain-behavior signatures, examines challenges in model optimization and specificity, and validates these findings across independent cohorts and clinical populations. By integrating evidence from large-scale datasets and multi-modal imaging, we highlight the implications of shared neural substrates for developing targeted therapeutic interventions and biomarker discovery in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Uncovering the Core Brain Networks for Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior

The two-streams hypothesis represents a foundational model in neuroscience for understanding how the primate brain processes visual information. Initially characterized by Milner and Goodale in 1992, this framework proposes that visual information exiting the primary visual cortex follows two distinct anatomical pathways with separate functional specializations [1]. The ventral stream, often termed the "what pathway," projects from the occipital lobe to the temporal lobe and is primarily responsible for object recognition, identification, and conscious visual perception. In contrast, the dorsal stream, or "where/how pathway," projects from the occipital lobe to the posterior parietal lobe and mediates spatial processing and the visual guidance of actions in real time [1] [2]. This functional dissociation provides a powerful framework for understanding how the brain converts visual inputs into perception and action, with profound implications for cognitive neuroscience, neuropsychology, and therapeutic development.

The historical development of this model reveals an evolving understanding of visual processing. The original "where" versus "what" distinction proposed by Ungerleider and Mishkin in 1982 was subsequently refined by Milner and Goodale to the "how" versus "what" dichotomy, emphasizing the dorsal stream's role in transforming visual information for motor control rather than spatial perception alone [1]. Recent research has further elaborated this framework, suggesting that each stream may contain specialized subsystems for processing different types of information. For instance, a 2024 connectivity review proposed that humans may have two distinct "what" streams (ventrolateral and superior temporal sulcus) and two "where" streams (ventromedial and dorsal), indicating greater complexity than the original binary distinction [3]. This refined understanding highlights the sophisticated organization of visual processing networks that support human cognition and behavior.

Anatomical and Functional Dissociation of the Two Streams

Core Structural and Functional Differences

The ventral and dorsal streams originate in the primary visual cortex (V1) and diverge into separate cortical pathways with distinct anatomical connections, physiological properties, and functional roles. The ventral stream projects downward from V1 through V2 and V4 to areas of the inferior temporal lobe, including the posterior inferotemporal (PIT), central inferotemporal (CIT), and anterior inferotemporal (AIT) areas [1]. Each visual area in this pathway contains a complete representation of visual space, with receptive fields increasing in size, latency, and complexity of tuning as information moves from V1 to AIT. This stream receives its primary input from the parvocellular layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus, which are specialized for processing detailed spatial information and color [1].

Conversely, the dorsal stream projects upward from V1 to the posterior parietal cortex, containing a detailed map of the visual field that is particularly adept at detecting and analyzing movements [1]. This pathway gradually transfers from purely visual functions in the occipital lobe to spatial awareness at its termination in the parietal lobe. The posterior parietal cortex is essential for "the perception and interpretation of spatial relationships, accurate body image, and the learning of tasks involving coordination of the body in space" [1]. This stream contains functionally specialized lobules, including the lateral intraparietal sulcus (LIP), where neurons produce enhanced activation during attention shifts or saccades toward visual stimuli, and the ventral intraparietal sulcus (VIP), which integrates visual and somatosensory information [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Ventral and Dorsal Visual Streams

| Factor | Ventral System (What) | Dorsal System (How) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Object recognition/identification | Visually guided behavior |

| Sensitivity | High spatial frequencies - details | High temporal frequencies - motion |

| Memory Dependence | Long-term stored representations | Only very short-term storage |

| Processing Speed | Relatively slow | Relatively fast |

| Conscious Awareness | Typically high | Typically low |

| Frame of Reference | Allocentric or object-centered | Egocentric or viewer-centered |

| Visual Input | Mainly foveal or parafoveal | Across retina |

| Monocular Vision Effects | Generally reasonably small effects | Often large effects (e.g., motion parallax) |

The functional differences between these streams extend to their relationship with conscious awareness. Research using continuous flash suppression (CFS) to render stimuli invisible has demonstrated that activity in ventral stream areas correlates strongly with subjective perceptual awareness, while dorsal stream activity remains comparatively unaffected by conscious perception [4]. For example, one fMRI study found that ventral body-sensitive areas showed significantly higher activity for consciously perceived body postures compared to invisible ones, whereas dorsal stream areas in the posterior intraparietal sulcus showed minimal dependence on subjective awareness [4]. This dissociation suggests that the dorsal stream can process visual information and guide behavior without conscious awareness, enabling automatic visuomotor control.

Neuropsychological Evidence from Brain Lesions

Evidence from patients with focal brain damage provides compelling support for the functional dissociation between the ventral and dorsal streams. Damage to the ventral stream typically results in various forms of visual agnosia, where patients can manipulate and orient objects correctly but cannot recognize or identify them. The seminal case of patient D.F., who developed severe visual form agnosia following carbon monoxide poisoning, demonstrates this dissociation strikingly [1]. Despite being unable to consciously perceive the size, shape, or orientation of objects, D.F. could accurately perform visuomotor tasks such as reaching and grasping, correctly adjusting her hand posture to objects she could not consciously identify [1] [2].

Conversely, damage to the dorsal stream can cause a range of spatial disorders while leaving object recognition intact. These include:

- Simultanagnosia: Patients can describe single objects but cannot perceive them as components of a set of details or objects in a context [1]

- Optic ataxia: Inability to use visuospatial information to guide arm movements toward objects [1]

- Hemispatial neglect: Unawareness of the contralesional half of space, often manifesting as ignoring objects or people on one side [1]

- Akinetopsia: Inability to perceive motion [1]

- Apraxia: Inability to produce voluntary movement in the absence of muscular disorders [1]

These neuropsychological dissections reveal the complementary specializations of each stream: the ventral stream for constructing conscious perceptual representations and the dorsal stream for enabling spatially guided actions.

Interactions Between the Two Visual Streams

Cross-Stream Integration and Coordination

Despite their functional specializations, the ventral and dorsal streams do not operate in isolation. A growing body of evidence indicates sophisticated bidirectional interactions between these pathways, enabling the integration of perceptual information with motor planning. As Milner (2017) notes, "The brain, however, does not work through mutually insulated subsystems, and indeed there are well-documented interconnections between the two streams" [2]. These interconnections allow for complex behaviors that require both object recognition and spatially precise actions.

The ventral stream contributes perceptual information to dorsal stream processing, enabling flexible, context-dependent visuomotor control. For instance, when grasping a tool, the ventral stream identifies the object and accesses semantic knowledge about its function, which then influences how the dorsal stream plans the appropriate grip and movement [2]. Neuroimaging studies have shown that tool identification involves both ventral stream regions for object recognition and dorsal stream areas for action-related processing [2]. This suggests that semantic knowledge about object manipulation retrieved through the ventral visual pathway can guide motor planning in dorsal stream areas.

Conversely, the dorsal stream provides spatial information to ventral stream processing, contributing to certain aspects of three-dimensional perceptual function. Posterior dorsal-stream visual analysis appears to play a role in constructing perceptual representations of spatial relationships between objects [2]. This cross-talk between streams enables the brain to coordinate object recognition with spatial processing, supporting complex behaviors such as navigating through environments while recognizing landmarks and avoiding obstacles.

Neural Synchronization During Shared Visual Experiences

Recent hyperscanning fMRI studies have revealed how distributed brain networks coordinate during shared visual experiences, engaging both visual streams in social contexts. When pairs of individuals jointly attend to visual stimuli, they exhibit inter-brain synchronization in specific neural networks. One study found "pair-specific inter-individual neural synchronization of task-specific activities in the right anterior insular cortex (AIC)-inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) complex, the core node of joint attention and salience network, and the right posterior superior temporal sulcus" [5].

This neural synchronization during shared visual experiences involves coordination between the default mode network (DMN), typically associated with internal mentation, and the salience network, linked through the right AIC-IFG complex [5]. This background synchronization represents "sharing the belief of sharing the situation" [5], suggesting that during joint attention, both ventral stream perceptual processing and dorsal stream spatial orienting mechanisms are coordinated between brains to enable shared experiences. This finding has significant implications for understanding the neural basis of social cognition and communication, particularly for disorders characterized by joint attention deficits.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Paradigms for Investigating Dual-Stream Processing

Research on the two visual streams employs diverse methodological approaches, including neuropsychological studies of patients with brain lesions, neuroimaging investigations in healthy participants, and behavioral paradigms that dissociate perceptual from motor responses. One powerful approach involves visual illusions that dissociate perceptual judgments from motor responses. For example, in the size-contrast illusion, where a target object appears larger or smaller due to surrounding context, participants' conscious perceptions are deceived by the illusion, but their grasping actions remain accurate [1]. This demonstrates that the dorsal stream processes veridical object properties for action guidance, while the ventral stream constructs perceptual representations influenced by contextual information.

Another influential method involves continuous flash suppression (CFS), which renders stimuli invisible by presenting dynamic noise patterns to one eye while presenting target stimuli to the other eye [4]. This paradigm has been used to investigate differences in how the two streams process conscious versus nonconscious visual information. One fMRI study using CFS found that "activity in the ventral body-sensitive areas was higher during visible conditions," while "activity in the posterior part of the bilateral intraparietal sulcus (IPS) showed a significant interaction of stimulus orientation and visibility" [4]. This provides evidence that dorsal stream areas are less associated with visual awareness than ventral stream regions.

Table 2: Key Experimental Paradigms in Dual-Stream Research

| Paradigm | Methodology | Stream Investigation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Illusions | Presentation of contextually biased visual stimuli | Dissociation between perceptual judgment (ventral) and motor response (dorsal) | Grasping actions escape perceptual illusions, indicating separate processing [1] |

| Continuous Flash Suppression | Dichoptic presentation of target stimulus and dynamic noise pattern | Differential response to conscious vs. nonconscious processing | Ventral stream activity correlates with awareness; dorsal stream processes unconscious information [4] |

| Neuropsychological Assessment | Testing patients with focal brain lesions | Functional dissociations after ventral or dorsal stream damage | Double dissociations between object recognition and visuomotor control [1] [2] |

| fMRI Hyperscanning | Simultaneous brain imaging of multiple participants during shared tasks | Neural synchronization during joint attention | Coordination between salience and default mode networks during shared experiences [5] |

| Optogenetic Inactivation | Targeted suppression of specific brain regions in animal models | Causal role of specific areas in attention and working memory | Dissociable neuronal substrates for feature attention and working memory [6] |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dual-Stream Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Platforms | fMRI, DTI, MEG | Mapping structural and functional connectivity; tracking neural activity in real time [5] [3] |

| Analysis Pipelines | NeuroMark, ICA, GLM | Decomposing neural networks; identifying individual differences; statistical modeling [7] |

| Visual Stimulation Software | PsychToolbox, Presentation | Presenting controlled visual stimuli; timing precision for behavioral paradigms [4] |

| Eye Tracking Systems | Pupil tracking, gaze pattern analysis | Quantifying visual attention and oculomotor control; correlating with neural activity |

| Computational Modeling Tools | Predictive coding models, connectionist networks | Theorizing stream interactions; simulating network dynamics [8] |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

Expanding the Dual-Stream Framework to Other Modalities

While initially developed to explain visual processing, the dual-stream framework has since been extended to other sensory modalities, particularly auditory processing. Similar to the visual system, the auditory system appears to comprise ventral and dorsal streams with distinct functional specializations [1]. The auditory ventral stream projects from the primary auditory cortex to the middle temporal gyrus and temporal pole, where auditory objects are converted into audio-visual concepts [1]. This pathway processes phonemes, syllables, and environmental sounds, supporting auditory identification and recognition.

In contrast, the auditory dorsal stream "maps the auditory sensory representations onto articulatory motor representations" [1]. This pathway is crucial for speech reproduction and phonological short-term memory, projecting from the primary auditory cortex to the posterior superior temporal gyrus and sulcus, then to the Sylvian parietal-temporal region (Spt), and finally to articulatory networks in the inferior frontal gyrus [1]. Damage to this pathway can cause conduction aphasia, characterized by an inability to reproduce speech despite preserved comprehension [1]. This cross-modal generalization of the dual-stream architecture suggests a fundamental principle of neural organization that separates perceptual identification from sensorimotor transformation.

Implications for Shared Brain Substrates Research

The dual-stream framework provides important insights for research on shared brain substrates across behavioral domains. The coordination between ventral and dorsal streams illustrates how specialized neural systems interact to support complex behaviors. This has particular relevance for understanding developmental disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and psychiatric conditions that affect perception-action integration.

For example, research on reading development has revealed how the left fusiform gyrus serves as an interface between visual and phonological systems, supporting the conversion of print to sound [9]. This region, sometimes called the visual word form area, demonstrates how visual processing in the ventral stream connects with language systems to support literacy. Longitudinal studies have shown that "both the development of Visual Matching and reading accuracy were associated with cortical surface area of a cluster located in fusiform gyrus" [9], highlighting how cross-system integration supports complex cognitive skills.

Similarly, statistical learning research reveals how the brain detects and exploits regularities across cognitive domains, with emerging evidence suggesting interactions between statistical learning and emotional processes [8]. The integration of these processes likely involves coordination between ventral stream mechanisms for pattern recognition and dorsal stream mechanisms for attention and spatial processing, moderated by emotional systems such as the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex.

The dual-stream model of visual processing continues to provide a powerful framework for understanding how the brain bridges perception and action. The functional dissociation between the ventral "what" pathway and dorsal "where/how" pathway represents a fundamental organizational principle of the primate brain, with implications extending to auditory processing, language, social cognition, and beyond. While each stream possesses specialized functions, their sophisticated integration enables the flexible, context-appropriate behaviors that characterize human experience.

Future research directions include further elucidating the precise mechanisms of cross-stream communication, understanding how these systems develop across the lifespan, and investigating how their disruption contributes to neurological and psychiatric disorders. The ongoing refinement of neuroimaging methods, such as dynamic connectivity analysis and multimodal fusion approaches [7], promises to reveal increasingly detailed insights into how these distributed networks coordinate to support human cognition. As our understanding of these systems deepens, so too will our ability to develop targeted interventions for disorders affecting perception, action, and their integration.

Emerging evidence from neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies reveals a fundamental dissociation in how the cerebral hemispheres support memory for complex visual scenes. This whitepaper synthesizes recent findings demonstrating that visual scene memory is supported by a bi-hemispheric network characterized by right temporo-parietal versus left temporo-occipital dominance. This structural asymmetry provides a paradigmatic case for understanding how specialized neural architectures within shared brain substrates give rise to distinct cognitive functions, with significant implications for targeted therapeutic interventions in neuropsychiatric disorders affecting memory systems.

The human brain exhibits remarkable functional specialization between its hemispheres, a phenomenon known as hemispheric dominance or lateralization [10]. This specialization is not merely descriptive but represents a fundamental organizational principle that increases neural processing capacity and enables complementary computational strategies [10]. Traditionally, hemispheric specialization has been studied primarily in domains such as language, with the left hemisphere dominating analytical and sequential processing, while the right hemisphere excels at holistic and coarse-grained tasks [10].

Within this broader framework of shared brain substrates research, the neural architecture supporting memory represents a compelling model system for investigating how specialized networks within each hemisphere contribute to complex cognitive functions. Recent lesion-behavior mapping studies have revealed a striking dissociation between right temporo-parietal and left temporo-occipital regions in supporting different aspects of visual scene memory [11]. This anatomical specialization mirrors functional distinctions observed in healthy populations and provides a neurobiological basis for understanding the cognitive hierarchy of memory processes.

Understanding these specialized networks has profound implications for drug development professionals targeting memory dysfunction in neurological and psychiatric disorders. The precise mapping of these networks enables more targeted therapeutic approaches that can account for the differential vulnerability of memory subsystems across various pathological conditions.

Quantitative Synthesis of Hemispheric Specialization Findings

Behavioral and Lesion Mapping Evidence

A recent lesion-behavior mapping study conducted with 93 first-event stroke patients provides compelling quantitative evidence for the hemispheric specialization in memory networks [11]. The study employed the WMS-III Family Pictures subtest to assess memory for different scene elements across immediate and delayed conditions.

Table 1: Behavioral Performance in Visual Scene Memory Tasks Following Hemispheric Lesions

| Memory Domain | Right Hemisphere Damage (RHD) | Left Hemisphere Damage (LHD) | Performance Hierarchy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character Identity | Significant impairment vs. controls | Less impaired than RHD | Highest scores |

| Spatial Location | Significant impairment vs. controls | Moderate impairment | Intermediate scores |

| Action Memory | Significant impairment vs. controls | Less impaired than RHD | Lowest scores |

| Overall Pattern | Generalized impairment across domains | More selective deficits | Identity > Location > Action |

The voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM) analysis revealed markedly distinct neural substrates for memory processes in each hemisphere [11]:

- Right hemisphere network: Dominated by large voxel clusters in middle and superior temporal gyri and inferior parietal regions

- Left hemisphere network: Dominated by large voxel clusters in temporo-occipital and medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions

This double dissociation provides strong evidence for complementary but distinct processing streams across hemispheres, with the right temporo- parietal system supporting integrated multi-element scene representation and the left temporo-occipital system contributing to item-specific memory processes.

Network-Level Asymmetries in Structural and Functional Connectivity

Beyond regional specialization, graph theoretical analyses of structural and functional brain networks have revealed fundamental asymmetries in topological organization that underlie hemispheric specialization in memory processes.

Table 2: Hemispheric Asymmetries in Brain Network Topology Related to Memory Functions

| Network Property | Left Hemisphere Characteristics | Right Hemisphere Characteristics | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Efficiency | More regional/central architecture | Higher global efficiency and interconnectivity | RH better suited for integrated scene representation |

| Local Clustering | Language-associated regions show higher clustering | Visuospatial regions show higher clustering | Domain-specific specialization |

| White Matter Tracts | Leftward asymmetry in arcuate fasciculus [12] | Rightward asymmetry in frontal tracts [12] | Structural basis for functional lateralization |

| Small-World Properties | Preserved but with leftward asymmetry in path length [13] | Preserved with rightward efficiency advantage [13] | Complementary computational strategies |

Studies examining community-dwelling older adults have found that these topological asymmetries are associated with behavioral performance across various cognitive domains, including memory [13]. The preservation of these asymmetries throughout the lifespan suggests their fundamental role in supporting complex cognitive functions, though normal aging may reduce the degree of functional asymmetry in some systems.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) Protocol

The seminal study on visual scene memory substrates [11] employed a rigorous VLSM protocol with the following key methodological components:

Subject Selection and Characterization:

- 93 first-event stroke patients (54 right-hemisphere damaged, 39 left-hemisphere damaged) in sub-acute phase

- Careful exclusion of patients with previous neurological or psychiatric history

- Comprehensive neuropsychological assessment including WMS-III Family Pictures subtest

- Matched healthy controls for comparison

Memory Assessment Protocol:

- Administration of Family Pictures task assessing memory for characters' identity, actions, and locations

- Both immediate and delayed recall conditions

- Standardized scoring procedures following WMS-III guidelines

- Hierarchical scoring of identity > location > action memory domains

Imaging and Analysis Pipeline:

- High-resolution structural MRI acquisition

- Manual lesion delineation by trained neurologists

- Spatial normalization of lesion maps to standard template space

- Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping using nonparametric permutation tests

- Conjunction analyses to identify regions specifically implicated in distinct memory domains

- False discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons

This protocol represents the current gold standard for lesion-deficit mapping studies and provides a robust methodological framework for investigating structure-function relationships in the human brain.

Functional Connectivity and Network Analysis Protocols

For investigating the network-level asymmetries in memory systems, several established protocols have been developed:

Resting-State fMRI Protocol for Functional Connectivity [14]:

- Data acquisition: Eyes-open resting state with fixation, minimum 8-minute scan duration

- Preprocessing: Slice timing correction, motion realignment, normalization to MNI space

- Nuisance regression: Removal of white matter, CSF, and motion parameters

- Band-pass filtering: Typical frequency range 0.01-0.1 Hz

- Region of interest (ROI) definition: Based on AAL atlas or functionally defined regions

- Connectivity calculation: Pearson correlation between ROI time series

- Graph theory metrics: Degree centrality, clustering coefficient, path length, betweenness centrality

Structural Connectivity Analysis Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging [12]:

- DTI acquisition: Minimum 12 diffusion directions, b-value=1000 s/mm²

- Tractography: Fiber assignment by continuous tracking (FACT) algorithm

- Network construction: AAL atlas for node definition, fiber count for edge weights

- Thresholding: Minimum 3 fibers between regions for reliable connection

- Asymmetry indices: Calculation of lateralization metrics for network properties

- Statistical analysis: Nonparametric permutation testing for hemispheric differences

These complementary approaches allow for comprehensive characterization of both structural and functional asymmetries in memory networks, providing insights into the neurobiological mechanisms underlying hemispheric specialization.

Visualization of Hemispheric Memory Networks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Investigating Hemispheric Memory Specialization

| Research Tool | Specification/Protocol | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| WMS-III Family Pictures Subtest | Standardized administration and scoring | Assessment of identity, location, and action memory in scene recall [11] |

| Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) | Nonparametric permutation testing with FDR correction | Mapping structure-function relationships in brain-damaged populations [11] |

| Resting-State fMRI | 3T scanner, 8-min acquisition, 0.01-0.1 Hz bandpass filtering | Investigation of functional connectivity in memory networks [14] |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging | 12+ directions, b=1000 s/mm², FACT algorithm | Reconstruction of white matter pathways supporting memory systems [12] |

| AAL Atlas | 90 cortical and subcortical regions (45 per hemisphere) | Standardized ROI definition for connectivity analyses [12] |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Degree centrality, path length, betweenness centrality | Quantification of network topology and hemispheric asymmetries [13] [12] |

| Dichotic Listening Task | Simultaneous auditory stimulus presentation | Behavioral assessment of functional lateralization [10] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The evidence for right temporo-parietal versus left temporo-occipital dominance in memory networks represents a significant advancement in our understanding of how shared brain substrates support specialized cognitive functions. This dissociation aligns with the broader framework of hemispheric specialization, where the left hemisphere typically engages in fine-grained, analytical processing, while the right hemisphere supports holistic, integrative functions [10]. In the domain of memory, this translates to left-hemispheric dominance for item-specific memory processes supported by temporo-occipital regions within the ventral visual stream, and right-hemispheric dominance for spatial and contextual binding processes supported by temporo-parietal regions within the dorsal stream and core recollection network [11].

From a clinical perspective, these findings have important implications for understanding memory dysfunction in neurological and psychiatric disorders. For instance, schizophrenia research has revealed atypical lateralization patterns that may contribute to both cognitive impairments and symptom severity [14]. Similarly, normal aging is associated with reductions in functional asymmetry that may reflect compensatory mechanisms or pathological changes [13]. For drug development professionals, these specialized networks represent potential targets for more precise therapeutic interventions that can address specific aspects of memory dysfunction rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

Future research should focus on integrating multimodal neuroimaging approaches with detailed cognitive assessment to further delineate the dynamic interactions between these specialized networks. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the development and aging of these asymmetrical networks will provide crucial insights into their plasticity and vulnerability across the lifespan. The continued refinement of our understanding of hemispheric specialization in memory networks will not only advance fundamental neuroscience knowledge but also inform the development of targeted interventions for memory disorders.

The core recollection network (CRN) represents a distributed brain system essential for the detailed, context-rich retrieval of past experiences, known as episodic memory. This network integrates medial temporal, frontal, and parietal regions to support the successful encoding and retrieval of autobiographical events. Understanding the CRN's functional anatomy and the causal relationships between its nodes is a central pursuit in cognitive neuroscience, with significant implications for diagnosing and treating memory disorders. Framed within broader research on shared brain substrates, this whitepaper synthesizes current evidence from lesion studies, intracranial recordings, and functional neuroimaging to detail the CRN's architecture, its response to prediction errors, and its role in binding distinct memory elements. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a current, in-depth technical guide to the network's operations and the experimental methods used to interrogate it.

Network Components and Functional Anatomy

The core recollection network is a hierarchically organized system where specific hubs mediate distinct cognitive operations, from binding features into coherent traces to monitoring retrieval outcomes. The table below summarizes the key brain regions and their proposed functions within the CRN.

Table 1: Key Hubs of the Core Recollection Network

| Brain Region | Sub-Region | Proposed Function in CRN | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial Temporal Lobe | Hippocampus | Binding item and contextual information; encoding novel solutions. | iEEG shows gamma power discriminates correct recall [15]. fMRI links activity to insight-driven memory [16]. |

| Medial Temporal Lobe | Parahippocampal Cortex | Processing contextual and spatial information. | Activated by moderate prediction errors during memory updating [17]. |

| Frontal Lobe | Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG) | Signaling prediction errors (PEs) during memory updating. | fMRI shows robust activation for all PEs, regardless of type/strength [17]. |

| Frontal Lobe | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) | Memory monitoring and decision-making during retrieval. | iEEG shows power increase preceding list intrusions [15]. |

| Parietal Lobe | Angular Gyrus | A hub integrating memory features; supports vivid recollection. | iEEG shows gamma power decrease precedes intrusions; has unique PAC [15]. |

| Parietal Lobe | Precuneus | Supporting self-referential processing and scene construction. | iEEG shows gamma activity discriminates accurate recall [15]. Meta-review confirms CRN role [18]. |

| Parietal Lobe | Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) | A midline hub within the default mode network, involved in memory retrieval. | Part of the putative core episodic retrieval network [15]. |

The functional interactions between these regions can be visualized as a network, where the hippocampus serves as a central binding agent, coordinating with domain-specific cortical hubs to form and reconstruct coherent memories.

Evidence from Lesion and Intracranial Studies

Lesion-behavior mapping and intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) provide causal evidence for the CRN's functional anatomy, revealing hemispheric asymmetries and dissociable contributions.

Lesion-Behavior Mapping of Visual Scene Memory

A recent voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM) study of 93 stroke patients dissociated the roles of the left and right hemispheres in recalling different elements of a visual scene (identity, location, action) from the WMS-III Family Pictures subtest [19]. The study revealed a marked hemispheric dissociation: the right-hemisphere network was dominated by middle and superior temporal and inferior parietal regions, whereas the left-hemisphere network was dominated by temporo-occipital and medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions [19]. Furthermore, the right hemisphere contained more regions specifically implicated in memory for particular scene elements, whereas the left hemisphere network acted in a more non-specific manner [19]. This highlights a right-hemispheric bias in the parietal and temporal components for detailed scene recollection.

Intracranial EEG (iEEG) and Network Connectivity

A stereo-EEG study involving 100 patients performing a free recall task provided high-resolution temporal and spatial data on the CRN [15]. The key methodology involved analyzing high-frequency activity (HFA/gamma band: 44–100 Hz) in the 1000 ms preceding vocalization during correct recalls versus prior list intrusions (PLIs). The findings demonstrated that gamma activity in the angular gyrus, precuneus, and posterior hippocampus successfully discriminated between accurate and inaccurate recall [15]. A critical discovery was a significant power decrease in the left angular gyrus preceding PLIs, whereas the DLPFC showed a power increase during these errors, suggesting a failure of the parietal hub followed by compensatory frontal monitoring [15]. Connectivity analysis revealed significant hemispheric asymmetry, with sparser functional connections in the left hemisphere, except for elevated connectivity between the left DLPFC and left angular gyrus [15]. This specific pathway is hypothesized to support frontal monitoring of parietal memory representations.

Insights from Functional Neuroimaging

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies elucidate how the CRN supports dynamic cognitive processes like memory formation and updating, highlighting its responsiveness to cognitive events.

Prediction Errors and Memory Updating

An fMRI study investigated how the type and strength of episodic prediction errors (PEs) influence memory updating for naturalistic dialogues [17]. The experimental protocol is summarized below.

Table 2: fMRI Protocol for Studying Prediction Errors in Memory

| Protocol Phase | Stimuli | Modification Type | fMRI Contrasts | Post-fMRI Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoding | Naturalistic dialogues | None | N/A | Recognition test for original and modified content. |

| Modification (in scanner) | Previously encoded dialogues | Surface: Changes in exact wording. Gist: Changes in meaning, to varying extents (weak/strong). | All PEs vs. baseline; Gist vs. Surface PEs; Parametric modulation by PE strength. |

The results revealed a dissociable neural response: the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) responded to all PEs, irrespective of type or strength, positioning it as a general PE detector [17]. In contrast, gist modifications specifically recruited the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex. Notably, only moderate-strength gist PEs impaired memory for the original content and triggered parahippocampal activity, suggesting a "sweet spot" for memory modification where the CRN is optimally engaged [17]. This protocol is visualized in the following workflow.

Representational Change and Insight-Driven Memory

A recent fMRI study investigated why solutions achieved through insight are better remembered, linking the CRN to creative problem-solving [16]. Participants identified difficult-to-recognize images (Mooney images) while undergoing fMRI; they rated their experience for suddenness, emotion, and certainty (the "Aha!" moment), and memory was tested five days later. The study tested two key insight components: a cognitive component (representational change, RC, measured as a shift in multivariate activity patterns in visual cortex) and an evaluative component (activity in amygdala and hippocampus). The results confirmed that both stronger RC in the ventral occipito-temporal cortex (VOTC) and increased hippocampal activity predicted better subsequent memory for insight solutions [16]. This demonstrates that the hippocampus, a central CRN node, works in concert with domain-specific cortex to create durable memories for reorganised information.

Synthesis and Data Integration

The convergence of evidence from multiple methodologies allows for the construction of an integrated model of CRN function, with quantitative data summarizing its roles.

The quantitative findings from the cited studies are synthesized in the table below, providing a clear comparison of key results.

Table 3: Synthesis of Quantitative Findings from Core Recollection Network Studies

| Study & Method | Key Behavioral Finding | Key Neural Correlation / Effect | Association with Subsequent Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Mapping (n=93) [19] | RHD patients impaired vs. controls; Performance: Identity > Location > Action. | LH lesions: temporo-occipital/MTL. RH lesions: temporo-parietal. | Specific RH regions linked to memory for action and location. |

| iEEG (n=100) [15] | Prior list intrusions (PLIs) in free recall. | Gamma power ↓ in Angular Gyrus before PLIs; Gamma power ↑ in DLPFC during PLIs. | Accurate recall predicted by gamma in AG, precuneus, posterior hippocampus. |

| fMRI-PE (Dialogue) [17] | Weak gist changes impaired memory for original content. | IFG: all PEs. Parahippocampal: moderate gist PEs. Hippocampus: gist PEs. | Moderate PEs induced memory changes via parahippocampal activity. |

| fMRI-Insight (n=31) [16] | High-insight solutions faster, more accurate, better remembered. | RC in VOTC; Activity in amygdala & hippocampus. | RC and hippocampal activity positively associated with memory. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and methodological solutions for investigating the Core Recollection Network.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Reagent / Method | Function in CRN Research | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) | Statistically maps behavioral deficits onto brain lesion topography to infer critical brain regions. | Identifying dissociable networks for scene element memory in stroke patients [19]. |

| Stereo-EEG (sEEG) with High-Frequency Activity (HFA) Analysis | Records local field potentials directly from brain regions with high temporal resolution; HFA (44-100 Hz) is a proxy for local neuronal firing. | Discriminating accurate vs. inaccurate recall and analyzing fronto-parietal connectivity [15]. |

| Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) in fMRI | Detects subtle, distributed activation patterns in fMRI data that are not evident in univariate analyses. | Measuring representational change (RC) in visual cortex during insight problem solving [16]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression with Functional Connectivity (FC) | A machine learning approach that uses whole-brain FC matrices to predict individual differences in behavioral traits. | Predicting cognitive performance from resting-state and task-based FC in large cohorts [20]. |

| Prediction Error (PE) Paradigms | Experimental designs that introduce mismatches between expected and actual events to probe memory updating mechanisms. | Testing how surface/gist modifications to dialogues trigger brain activity and alter memory [17]. |

Neuromodulatory systems are integral to the brain's functional architecture, governing cognitive and behavioral processes through complex chemical signaling. This whitepaper examines the dopaminergic, cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic systems, highlighting their roles as fundamental organizers of brain-wide neural circuits. Rather than operating in isolation, these systems form an integrated network that shapes behavioral domains by modulating large-scale brain dynamics. Emerging research mapping neurotransmitter receptors to macroscale brain organization provides compelling evidence for shared brain substrates across cognitive, personality, and mental health domains. Understanding these neuromodulatory interactions offers transformative potential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for neurological and psychiatric disorders, particularly through their influence on cognitive flexibility and neural plasticity. For drug development professionals, these insights reveal new opportunities for targeting specific receptor profiles and network dynamics that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries.

Neuromodulatory systems consist of relatively small pools of neurons located primarily in the brainstem, midbrain, and basal forebrain that project widely throughout the central nervous system to regulate neural excitability, synaptic transmission, and network dynamics [21] [22]. Unlike classic neurotransmitters that mediate fast point-to-point signaling, neuromodulators operate through volume transmission, influencing broad neural populations via second messenger cascades with effects lasting from hundreds of milliseconds to several minutes [23]. The four primary systems—dopaminergic, cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic—collectively track environmental signals including risks, rewards, novelty, effort, and social cooperation, thereby providing a foundation for higher cognitive functions and complex behaviors [21]. These systems demonstrate both specialized functions and significant interactions, creating a complex regulatory landscape that shapes behavioral output across multiple domains.

Recent advances in neuroimaging and computational neuroscience have revealed that these systems do not operate in isolation but rather form an integrated network that collectively shapes brain-wide neural circuits and behavioral outcomes [24]. The receptor distributions of these neuromodulators align closely with structural and functional connectivity patterns, suggesting they play a fundamental role in organizing macroscale brain dynamics [24]. This perspective frames neuromodulatory systems as key mediators between molecular mechanisms and system-level brain organization, providing a crucial link for understanding how biochemical signaling translates to complex behavioral programs.

System-Specific Neuromodulatory Pathways

Dopaminergic System

The dopaminergic system originates primarily from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), projecting to multiple target regions including the striatum, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [21]. This system forms several distinct pathways: the nigrostriatal pathway (SNc to dorsal striatum) crucial for motor control, the mesolimbic pathway (VTA to ventral striatum) central to reward processing, and the mesocortical pathway (VTA to prefrontal cortex) important for executive functions [21]. Dopamine exerts its effects through D1-like (D1, D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, D4) receptor families, with differential activation depending on tonic versus phasic firing patterns [21].

Dopaminergic signaling is central to reinforcement learning, with phasic dopamine responses closely resembling temporal difference reward prediction error signals used in machine learning algorithms [21]. Beyond reward processing, dopamine also responds to salient, novel, and uncertain stimuli, playing a key role in motivation, decision-making, and cognitive control [21]. Abnormalities in dopaminergic signaling are implicated in Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, addiction, and mood disorders, making this system a prime target for therapeutic interventions [21].

Table 1: Dopaminergic System Organization

| Component | Characteristics | Functions | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin Nuclei | Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA), Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNc) | Midbrain nuclei with specialized cell groups | Parkinson's (SNc degeneration), Schizophrenia (VTA dysregulation) |

| Major Pathways | Mesolimbic, Mesocortical, Nigrostriatal | Reward, motivation, executive function, motor control | Addiction (mesolimbic), Cognitive deficits (mesocortical) |

| Receptor Types | D1-like (D1, D5), D2-like (D2, D3, D4) | Differential effects on direct/indirect pathways, cAMP signaling | Antipsychotics (D2 antagonists), Parkinson's treatments |

| Signaling Modes | Tonic (baseline) vs. Phasic (burst) | Sustained modulation vs. event-related coding | Addiction (phasic dysregulation), Depression (tonic deficits) |

| Computational Roles | Reward prediction error, incentive salience, uncertainty | Reinforcement learning, decision-making, exploration | Computational psychiatry models for mental disorders |

Cholinergic System

The cholinergic system originates primarily from the basal forebrain, including the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM), medial septum, and diagonal band of Broca, with additional contributions from the pedunculopontine (PPT) and laterodorsal tegmental (LDT) nuclei in the brainstem [22]. These neurons project widely throughout the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, with a single cholinergic neuron often innervating multiple brain regions through extensive axonal arbortizations [22]. The striatum represents an exception, possessing its own local population of cholinergic interneurons for regional modulation [22].

Acetylcholine exerts its effects through both ionotropic nicotinic receptors (nAChR) and metabotropic muscarinic receptors (mAChR), with differential receptor distributions across brain regions contributing to functional specialization [23] [22]. The cholinergic system is critically involved in sensory processing, attention, learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity [22]. Recent work has highlighted its role in attentional effort, orienting responses, and detecting behaviorally significant stimuli, with particularly important functions in regulating interactions between prefrontal cortex and sensory cortices during cognitive tasks [22].

Noradrenergic System

The noradrenergic system originates primarily from the locus coeruleus (LC), a small nucleus in the brainstem containing approximately 15,000 neurons in rodents that project broadly throughout the central nervous system [23] [22]. Despite its relatively small size, this system plays a major role in regulating arousal, vigilance, and the efficiency of external sensory processing [22]. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) is often released steadily to prepare glial cells for calibrated responses and plays important roles in suppressing neuroinflammatory responses, stimulating neuronal plasticity through long-term potentiation (LTP), regulating glutamate uptake by astrocytes, and consolidating memory [23].

Recent research has revealed a more complex role for the noradrenergic system beyond simple arousal, with involvement in memory formation, executive function, attention, cognitive flexibility, and decision-making [22]. The system demonstrates a sophisticated topographic organization that allows for region-specific modulation of cortical function, enabling targeted neuromodulation based on behavioral requirements [22]. Noradrenaline exerts its effects through α1, α2, and β adrenergic receptors, each with distinct signaling mechanisms and functional consequences that contribute to the system's versatile modulatory capabilities.

Serotonergic System

The serotonergic system originates from the raphe nuclei, with the caudal dorsal raphe nucleus projecting primarily to subcortical regions and the rostral dorsal raphe nucleus projecting to cortical areas [23]. This system regulates a wide range of functions including mood, appetite, sleep, aggression, and impulsivity [23]. It's noteworthy that the majority (80-90%) of the body's serotonin is found in the gastrointestinal tract, with only about 10% present in the brain [23].

Serotonin acts through at least 14 different receptor types (5-HT1 to 5-HT7 families), most of which are G-protein coupled receptors except for the 5-HT3 receptor which is ligand-gated ion channel [23]. This receptor diversity enables complex modulation of neural circuits and contributes to the system's involvement in numerous behavioral domains. The serotonergic system demonstrates particularly important interactions with the dopaminergic system, often exerting opposing effects on common neural circuits, which has significant implications for both normal function and psychiatric disorders [21].

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Major Neuromodulatory Systems

| System | Origin Nuclei | Primary Receptors | Key Functions | Therapeutic Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic | VTA, SNc | D1-like, D2-like | Reward processing, motivation, motor control, executive function | Parkinson's, schizophrenia, addiction, depression |

| Cholinergic | Nucleus Basalis of Meynert, PPT/LDT nuclei | Muscarinic (M1-M5), Nicotinic | Attention, learning, memory, sensory processing | Dementia, Alzheimer's, cognitive disorders |

| Noradrenergic | Locus Coeruleus | α1, α2, β adrenergic | Arousal, vigilance, cognitive flexibility, memory consolidation | ADHD, depression, anxiety disorders |

| Serotonergic | Raphe Nuclei | 5-HT1-7 (except ionotropic 5-HT3) | Mood, appetite, sleep, aggression, impulsivity | Depression, anxiety, OCD, migraine |

Shared Brain Substrates and Behavioral Domains

Neurotransmitter Systems and Macroscale Brain Organization

Recent advances in neuroimaging have enabled the construction of comprehensive atlases of neurotransmitter receptor distributions, revealing how these systems are situated within macroscale brain architecture [24]. Analysis of 19 different neurotransmitter receptors and transporters across nine neurotransmitter systems from over 1,200 healthy individuals demonstrates that receptor profiles align closely with structural connectivity and mediate neurophysiological oscillatory dynamics and resting-state functional connectivity [24]. This chemoarchitectural organization follows a topographic gradient that separates extrinsic and intrinsic psychological processes, providing a molecular basis for the organization of behavioral domains.

Research using the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study dataset with 1,858 children has shown that predictive network features for cognitive performance, personality scores, and mental health assessments demonstrate both shared and unique patterns across behavioral domains [20]. While traits within each behavioral domain are predicted by similar network features, these predictive features are distinct across domains, suggesting a nested hierarchy of neural substrates supporting related behaviors [20]. This organization helps explain comorbidity patterns in psychiatric disorders and provides a framework for understanding how targeted neuromodulation might affect multiple behavioral domains.

Cross-System Interactions and Functional Integration

The neuromodulatory systems do not operate in isolation but engage in complex interactions at multiple levels—from functional and anatomic integration to intertwined signaling pathways and co-release at synapses [22]. For instance, the cholinergic and noradrenergic systems demonstrate significant interactions in regulating attention, learning, and decision-making processes [22]. The nucleus basalis receives noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus, while cholinergic inputs to the locus coeruleus have been documented, creating reciprocal regulatory loops [22].

Computational models have proposed distinct but interacting roles for these systems in learning and decision-making. One influential framework suggests that dopamine signals reward prediction error, serotonin controls the temporal discounting of future rewards, and norepinephrine regulates the speed of memory updating [21]. Such models provide a theoretical foundation for understanding how these systems coordinate to produce adaptive behavior while also explaining how imbalances in one system might disrupt function across multiple behavioral domains.

Experimental Methodologies and Research Protocols

Multimodal Neuroimaging Approaches

Contemporary research on neuromodulatory systems employs multimodal neuroimaging approaches to link molecular mechanisms with system-level brain organization. Positron emission tomography (PET) with specific radiotracers enables quantification of receptor densities and transporter availability across different neurotransmitter systems [24]. When combined with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which provides detailed structural and functional information, researchers can establish precise spatial correspondence between receptor distributions and brain networks [24]. Functional MRI (fMRI) during both resting-state and task conditions further reveals how neuromodulatory systems shape brain dynamics and support cognitive processes [20] [24].

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) provides complementary information about neurophysiological oscillatory dynamics with high temporal resolution, allowing researchers to connect receptor distributions with neural population activity [24]. The integration of these multimodal datasets requires sophisticated computational approaches, including kernel regression methods for predicting individual differences in behavior from functional connectivity patterns [20], and receptor similarity analyses that quantify the similarity of receptor fingerprints between different brain regions [24].

Behavioral Assessment and Computational Modeling

Comprehensive behavioral assessment across multiple domains is essential for linking neuromodulatory function to specific behavioral programs. The ABCD study exemplifies this approach with its battery of neurocognitive tests, personality assessments, and mental health evaluations [20]. Critical to this endeavor is the examination of multiple behavioral measures within the same individuals, which enables researchers to identify both shared and unique predictive network features across cognitive performance, impulsivity-related personality traits, and mental health assessments [20].

Computational models provide a theoretical framework for interpreting empirical findings and generating testable hypotheses about neuromodulatory function. Reinforcement learning models, particularly those based on temporal difference learning algorithms, have been highly successful in characterizing dopaminergic function [21]. More recent models have extended this approach to other neuromodulatory systems, proposing specific computational roles for norepinephrine in controlling uncertainty-driven exploration and acetylcholine in regulating learning rate and attention [21]. These models increasingly incorporate interactions between multiple neuromodulatory systems, reflecting the growing recognition of their interdependent functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Neuromodulatory System Investigation

| Reagent/Methodology | Function/Application | Example Uses | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PET Radioligands | Quantify receptor availability and density in vivo | Mapping D2 receptors with [11C]raclopride, serotonin transporters with [11C]DASB | Tracer kinetic modeling, reference region selection, partial volume correction |

| Receptor-Specific Antibodies | Immunohistochemical localization of receptors | Post-mortem validation of receptor distributions, cellular localization | Specificity validation, epitope preservation in tissue preparation |

| Chemogenetic Tools (DREADDs) | Selective remote control of neuronal activity | Pathway-specific neuromodulation, testing causal behavioral contributions | Receptor localization, temporal resolution limitations |

| Optogenetic Constructs | Precise temporal control of specific neuronal populations | Cell-type-specific activation/inhibition, circuit mapping | Light delivery limitations, tissue penetration considerations |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | Real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter release | GRAB sensors for dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine | Sensitivity and specificity validation, calibration requirements |

| Computational Models | Theoretical frameworks for hypothesis generation | Reinforcement learning models, network dynamics simulations | Parameter estimation, model validation with empirical data |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Strategies

The understanding of neuromodulatory systems as organizers of shared brain substrates has profound implications for drug development. Rather than targeting single receptors in isolation, future therapeutics may aim to restore balance across multiple interacting systems [21] [24]. The recognition that different behavioral domains share common neural substrates suggests that treatments effective for one condition might show efficacy for others with overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms [20] [24]. This perspective encourages a transdiagnostic approach to neuropsychiatric drug development that focuses on dimensional aspects of psychopathology rather than categorical diagnoses.

Advanced neuroimaging techniques now enable the identification of individual differences in receptor distributions and network organization, paving the way for personalized therapeutic approaches [24]. By mapping an individual's unique neurochemical architecture, medications could be tailored to target their specific pattern of dysregulation [24]. Furthermore, the development of brain signatures as robust measures of behavioral substrates [25] provides objective biomarkers for tracking treatment response and identifying likely responders to specific therapeutic mechanisms.

Non-pharmacological neuromodulation approaches, including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and direct current stimulation (tDCS), can be optimized based on understanding of neurotransmitter receptor distributions [23] [24]. By targeting brain regions with specific receptor profiles, these techniques can be refined to produce more selective and sustained therapeutic effects. The integration of these approaches with cognitive training and psychosocial interventions represents a promising direction for developing comprehensive treatments that engage multiple mechanisms of neuroplasticity.

The dopaminergic, cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic systems form an integrated network that shapes behavioral programs through their influence on shared brain substrates. Rather than operating in isolation, these systems interact at multiple levels to regulate cognitive function, emotional processing, and adaptive behavior. Modern neuroimaging approaches have revealed how receptor distributions align with macroscale brain organization and shape neural dynamics, providing a chemoarchitectural basis for understanding individual differences in behavior and vulnerability to psychiatric disorders.

Future research should focus on characterizing the developmental trajectories of these neuromodulatory systems and their interactions across the lifespan [20]. Longitudinal studies tracking receptor changes alongside behavioral development will be particularly valuable for understanding risk and resilience factors for psychiatric disorders. Additionally, there is a need for more sophisticated computational models that can capture the dynamic interactions between multiple neuromodulatory systems and their collective influence on neural circuit function [21]. Finally, advancing our understanding of how genetic variation influences receptor expression and system function will be crucial for developing personalized approaches to neuromodulatory interventions.

For drug development professionals, these insights highlight the importance of moving beyond single-target approaches to consider system-level effects of pharmacological interventions. The development of compounds that selectively target receptor subtypes in specific brain circuits represents a promising direction for achieving therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects. Furthermore, the integration of multimodal neuroimaging into clinical trials will enhance our ability to identify target engagement and understand individual differences in treatment response, ultimately leading to more effective and personalized therapeutic strategies for neuropsychiatric disorders.

The question of whether cognitive functions are supported by domain-general mechanisms, which are utilized across multiple cognitive tasks, or domain-specific systems, which are dedicated to particular types of information, is fundamental to systems neuroscience. Evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and lesion-symptom mapping provides crucial, and often complementary, insights into this issue. Framed within the broader thesis of shared brain substrates for behavioral domains, this review synthesizes evidence from both methodologies to argue that complex cognition arises from a nested hierarchy of brain networks, where domain-specific processing is scaffolded by domain-general core systems and constrained by innate connectivity patterns. This framework is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to identify precise neural targets for cognitive enhancement and therapeutic intervention.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Defining Domain-Generality and Domain-Specificity

The debate between domain-general and domain-specific organization centers on the architecture of neural systems.

- Domain-General Systems: Refers to brain networks recruited by a wide array of cognitively demanding tasks, regardless of their specific content. The Multiple-Demand (MD) system, encompassing lateral and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, and regions within and surrounding the intraparietal sulcus, is a canonical example. It is hypothesized to form an integrating core for complex thought and behavior, responsible for flexible cognitive control [26].

- Domain-Specific Systems: Refers to neural networks specialized for processing particular categories of information (e.g., faces, places, tools) or supporting specific cognitive domains (e.g., language, arithmetic). A critical advancement is the Distributed Domain-Specific Hypothesis, which posits that domain-specificity is a property of networks, not single brain regions. These networks are individuated by the divergent computational goals required for successful processing of different domains, such as navigating versus inferring mental states [27].

A Integrated Model: The Nested Hierarchy

Evidence suggests that domain-general and domain-specific systems do not operate in isolation. Instead, they are organized in a nested hierarchy [26] [28] [27]:

- A domain-general core (MD system) provides top-down control and integrative capacity.

- This core interacts with, and is access by, domain-specific networks (e.g., for semantics, visuospatial processing).

- The organization of domain-specific areas in sensory cortex (e.g., occipito-temporal cortex) is thought to be scaffolded by innately constrained, domain-specific connectivity with downstream systems supporting action, navigation, and social cognition [27].

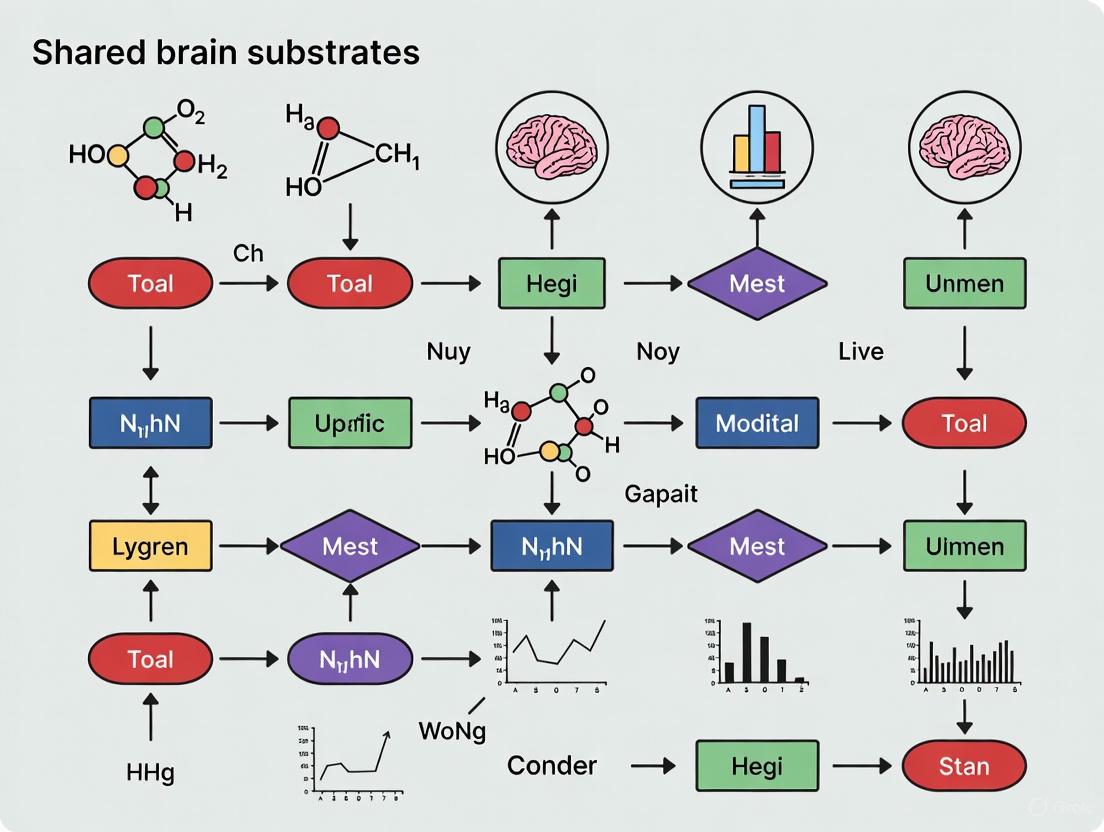

The following diagram illustrates this integrative framework and the flow of evidence supporting it.

Evidence from Functional Neuroimaging

Functional imaging provides a powerful tool for mapping brain activation patterns associated with cognitive tasks, revealing both domain-general and domain-specific networks.

The Domain-General Multiple-Demand (MD) System

A convergence of fMRI studies has delineated a consistent domain-general network. A seminal study using Human Connectome Project data and multimodal parcellation identified a core MD system of 10 widely distributed cortical areas per hemisphere that were most strongly activated and functionally interconnected during three diverse cognitive contrasts (working memory, relational reasoning, and math) [26]. This core MD system, embedded within a broader extended network of 27 areas, was concentrated in the fronto-parietal network but also engaged other resting-state networks. Key nodes included the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, and intraparietal sulcus. Activation in this system showed modest relative task preferences accompanying strong co-recruitment, supporting its role as an integrator and assembler of diverse cognitive components [26].

Shared and Unique Predictive Network Features

Large-scale predictive modeling offers a complementary approach. A study of 1,858 children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study used functional connectivity (FC) to predict individual differences in cognition, personality, and mental health [20]. This research demonstrated that:

- Predictive network features were distinct across behavioral domains (e.g., features predicting cognitive performance were different from those predicting mental health).

- Conversely, traits within a behavioral domain (e.g., different cognitive tests) were predicted by similar network features.

- These predictive network features were remarkably consistent between resting and task states, suggesting that core brain-behavior relationships are stable across brain states [20].

This table summarizes key quantitative findings from major functional imaging studies:

Table 1: Key Evidence from Functional Imaging Studies

| Study (Citation) | Sample Size | Key Domain-General Finding | Key Domain-Specific Finding | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakovics et al. (2022) [20] | 1,858 children (ABCD Study) | Predictive network features stable across rest & task states. | Features distinct across behavioral domains (cognition vs. mental health); shared within domains. | Kernel regression on whole-brain functional connectivity. |

| Assem et al. (2020) [26] | 449 adults (HCP) | Identified a core MD network of 10 areas/hemisphere, co-activated by working memory, reasoning, and math. | MD regions show mosaic functional preferences (modest task differentiation). | Multimodal parcellation & conjunction fMRI analysis of 3 task contrasts. |

| Chen et al. (2025) [28] | 32 adults | Semantic network activation was domain-general across numerical, geometrical, and verbal reasoning. | Domain-specific functional connectivity between semantic and visuospatial networks for mathematical processing. | fMRI activation and functional connectivity pattern analysis. |

Experimental Protocols in Functional Imaging

The following detailed methodology is synthesized from the protocols of the cited studies [20] [26].

- Participant Population & Data Acquisition: Large, well-characterized cohorts are essential. The ABCD study [20] recruited over 11,000 children, while the HCP [26] used data from 449 healthy adults. MRI acquisition involves high-resolution structural scans (T1-weighted) and functional scans (BOLD fMRI) during both resting-state and task conditions. Key tasks include the N-back (working memory), stop-signal task (response inhibition), monetary incentive delay (reward processing) [20], and relational reasoning tasks [26].

- Preprocessing Pipeline: Standard steps include distortion correction, motion realignment and scrubbing, slice-time correction, registration to structural images and standard space (e.g., MNI), and spatial smoothing. Nuisance regression (e.g., for white matter, CSF signals, motion parameters) is critical for FC analysis [20].

- Functional Connectivity & Activation Analysis: For FC, the brain is parcellated into regions (e.g., 419 regions in [20]), and time series are extracted. FC matrices are computed using Pearson's correlation between all region pairs. For task activation, general linear models (GLMs) are constructed with regressors for each task condition. Contrasts (e.g., 2-back > 0-back) identify task-activated voxels [26].

- Predictive Modeling & Statistical Validation: In predictive studies [20], machine learning models (e.g., kernel ridge regression) are trained on FC matrices to predict behavioral scores. A nested cross-validation procedure is mandatory to avoid overfitting, where an inner loop optimizes model parameters and an outer loop provides a unbiased performance estimate. Statistical significance is assessed via permutation testing.

Evidence from Lesion Studies

Lesion studies provide causal evidence by demonstrating which brain areas are necessary for specific cognitive functions, offering a vital complement to correlational fMRI data.

Domain-Specific Deficits from Focal Lesions

Lesion-symptom mapping (LSM) studies consistently show that focal damage can produce highly selective cognitive impairments, underscoring the necessity of specific neural substrates for domain-specific functions. A large-scale LSM study of 573 acute stroke patients used the Oxford Cognitive Screen to link deficits in five cognitive domains to distinct lesion patterns [29]:

- Language impairments were associated with damage to left-hemisphere fronto-temporal areas.

- Visuo-spatial deficits (visual neglect) were linked to right temporo-parietal lesions.

- Memory impairments were associated with specific clusters within the left insular and opercular cortices. In contrast, deficits in domains like executive function and praxis were not linked to highly localized voxels, suggesting they rely on more distributed, bilateral networks [29].

The Causal Role of Domain-General Networks

While less frequently the primary focus of lesion studies, damage to putative domain-general hubs can produce broad cognitive deficits. For instance, damage to frontal and parietal regions of the MD system is strongly associated with disorganized behavior and significant losses in fluid intelligence, supporting their domain-general role [26]. This indicates that domain-general nodes are critically involved in coordinating performance across multiple cognitive domains.

Table 2: Key Evidence from Lesion and Causal Studies

| Study (Citation) | Sample/Population | Domain-Specific Evidence | Domain-General Implication | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moore et al. (2022) [29] | 573 stroke patients | Distinct lesion loci for language (left fronto-temporal) and visual neglect (right temporo-parietal). | Deficits in executive function/praxis linked to distributed networks. | Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM) with routine clinical imaging. |

| Assem et al. (2020) [26] | Literature synthesis | N/A | Selective damage to frontal/parietal MD regions causes broad fluid intelligence deficits. | Integration of neuropsychological findings with functional imaging. |

| Mahon & Hickok (2022) [27] | Literature synthesis | Category-specific deficits (e.g., for tools, faces) from temporal lobe lesions; supports distributed domain-specific networks. | Connectivity constraints argue for innate scaffolding of domain-specificity. | Review of neuropsychological and functional MRI evidence. |

Experimental Protocols in Lesion-Symptom Mapping

The methodology for modern lesion-symptom mapping, as detailed in [29], involves a structured pipeline.

- Participant Recruitment & Cognitive Assessment: Patients with focal brain lesions (e.g., from stroke or trauma) are recruited in the acute or chronic phase. A standardized neuropsychological battery, such as the Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS), is administered to assess a range of domains (language, memory, attention, praxis, number processing). Patients are classified as impaired or not on each subtest based on normative data [29].

- Lesion Delineation and Normalization: For each patient, the lesion is manually traced onto their native structural MRI or CT scan by a trained researcher, blinded to the behavioral data. These lesion maps are then spatially normalized to a standard brain atlas (e.g., MNI) to allow for group-level analysis. This step often uses specialized software (e.g., MRIcron) and may involve cost-function masking to improve normalization accuracy.

- Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) Analysis: VLSM performs a statistical test (e.g., t-test, Brunner-Munzel test) at every voxel across the brain to determine if damage to that voxel is significantly associated with a behavioral deficit. The analysis compares the behavioral scores of the "lesioned" group (patients with damage at that voxel) versus the "non-lesioned" group (patients without damage at that voxel). Multiple comparisons are controlled for using family-wise error correction or false discovery rate [29].

The following diagram visualizes this causal inference workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and methodologies for research in this field, as derived from the analyzed studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study Data | A large-scale, longitudinal dataset of brain development in ~11,000 US children, including fMRI, structural MRI, genetics, and rich behavioral phenotyping. | Predicting individual differences in cognitive, personality, and mental health measures from functional connectivity [20]. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Multimodal Parcellation | A neurobiologically grounded atlas dividing the human cortex into 180 distinct areas per hemisphere based on cortical thickness, myelin content, and functional connectivity. | Precisely localizing the Multiple-Demand system and its subdivisions with improved anatomical specificity [26]. |

| Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) | A standardized bedside cognitive screening tool designed for stroke patients, assessing language, memory, number, praxis, and attention domains. | Lesion-symptom mapping of domain-specific cognitive impairments in a large, real-world patient cohort [29]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression | A machine learning algorithm that maps non-linear relationships between variables (e.g., functional connectivity matrices) and a target outcome (e.g., behavioral score). | Individual-level prediction of behavioral traits from whole-brain functional connectomes [20]. |