Mapping the Mind in Virtual Worlds: A Neuroscientific Guide to Brain Activity During Immersive VR Tasks

This article synthesizes current research on the neural correlates of immersive Virtual Reality (VR) experiences, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mapping the Mind in Virtual Worlds: A Neuroscientific Guide to Brain Activity During Immersive VR Tasks

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the neural correlates of immersive Virtual Reality (VR) experiences, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the neurobiological mechanisms underpinning VR-induced brain activity, including neuroplasticity and the modulation of brain waves like Alpha and Theta. The content details methodological approaches for measuring brain activity in VR environments, addresses key challenges in experimental design and data interpretation, and offers a critical appraisal of clinical validation studies. By integrating evidence from neurorehabilitation, cognitive training, and behavioral health, this review outlines how a deeper understanding of VR-brain interactions can inform the development of novel therapeutic and diagnostic tools.

The VR-Brain Connection: Uncovering the Neurobiological Mechanisms of Immersion

Virtual Reality (VR) technology has emerged as a ground-breaking tool in neuroscience, revolutionizing our understanding of neuroplasticity and its implications for neurological rehabilitation. By immersing individuals in simulated environments, VR induces profound neurobiological transformations, affecting neuronal connectivity, sensory feedback mechanisms, motor learning processes, and cognitive functions [1]. These changes highlight the dynamic interplay between molecular events, synaptic adaptations, and neural reorganization, emphasizing VR's potential as a therapeutic intervention for various neurological disorders. This technical guide, framed within broader research on brain activity during immersive VR tasks, delineates the core mechanisms through which VR modulates neuroplasticity, supported by quantitative evidence, detailed experimental protocols, and essential research tools.

Core Mechanisms of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

VR environments facilitate neuroplasticity by engaging multiple, simultaneous mechanisms that promote neural reorganization and functional recovery. The immersive and interactive nature of VR provides a unique platform for delivering controlled, intensive, and task-specific stimulation, which is crucial for driving plastic changes in the brain.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

| Mechanism | Description | Underlying Neural Process |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Sensory Fidelity | VR creates immersive, multi-sensory environments that provide rich, coherent, and contextually relevant stimuli. | Strengthens synaptic connections in sensory cortices through Hebbian plasticity; promotes multisensory integration. |

| Motor Learning & Feedback | Real-time visual and auditory feedback on movement performance in a safe, controlled environment. | Engages cerebellar-cortical loops and basal ganglia; refines internal models for movement via error-based learning. |

| Cognitive Engagement | Interactive scenarios requiring sustained attention, executive function, and rapid decision-making. | Drives adaptations in prefrontal cortex and hippocampal-prefrontal circuits, supporting memory and cognitive control. |

| Motivational & Reward Systems | Game-like elements, challenges, and rewards increase engagement and adherence to training. | Triggers dopaminergic release from the ventral tegmental area, reinforcing desired neural pathways and behaviors. |

The therapeutic application of these mechanisms is evident in conditions like stroke and traumatic brain injury. VR-based interventions can enhance motor recovery, cognitive rehabilitation, and emotional resilience by leveraging the brain's innate capacity for change [1]. For instance, VR sports games significantly improved cognitive function, coordination, and reaction speed in brain-injured patients, thereby boosting their learning motivation and engagement [2] [3]. This is achieved by engaging multiple cognitive domains through interactive and immersive experiences, which challenge memory, spatial awareness, and executive functions, thereby promoting neuroplasticity and cognitive recovery [2].

Quantitative Evidence from Clinical and Experimental Studies

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide robust, quantitative evidence supporting the efficacy of VR interventions. A primary outcome is the standardized mean difference (SMD), which measures the magnitude of the intervention effect.

Table 2: Meta-Analysis of VR Interventions for Cognitive Function in Brain-Injured Patients

| Study Parameter | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of RCTs Included | 12 | A substantial body of evidence from multiple independent studies. |

| Total Participants | 540 | A considerable sample size enhancing the statistical power and generalizability. |

| Pooled SMD | 0.88 (95% CI: 0.59, 1.17) | A large and statistically significant effect size (p=0.019) favoring the VR intervention group [2] [3]. |

| Heterogeneity (I²) | 51.9% | Indicates moderate variability among studies, accounted for by using a random effects model. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Robust findings | No single study disproportionately influenced the overall results. |

| Publication Bias | Not detected | Funnel plots were symmetric, suggesting no bias towards publishing only positive results. |

Beyond cognitive metrics, studies utilizing advanced molecular imaging techniques and computational modeling have begun to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underpinning these functional improvements. VR induces changes in neuronal connectivity, synaptic adaptations, and neural reorganization, which are fundamental to recovery [1]. The dynamic interplay between these molecular events and the immersive experience is key to VR's therapeutic potential.

Experimental Protocols for VR Research

To ensure the validity, reliability, and reproducibility of VR-based neuroplasticity research, adherence to detailed experimental protocols is paramount. The following workflow outlines a standardized methodology for a clinical RCT, akin to those analyzed in the meta-analysis.

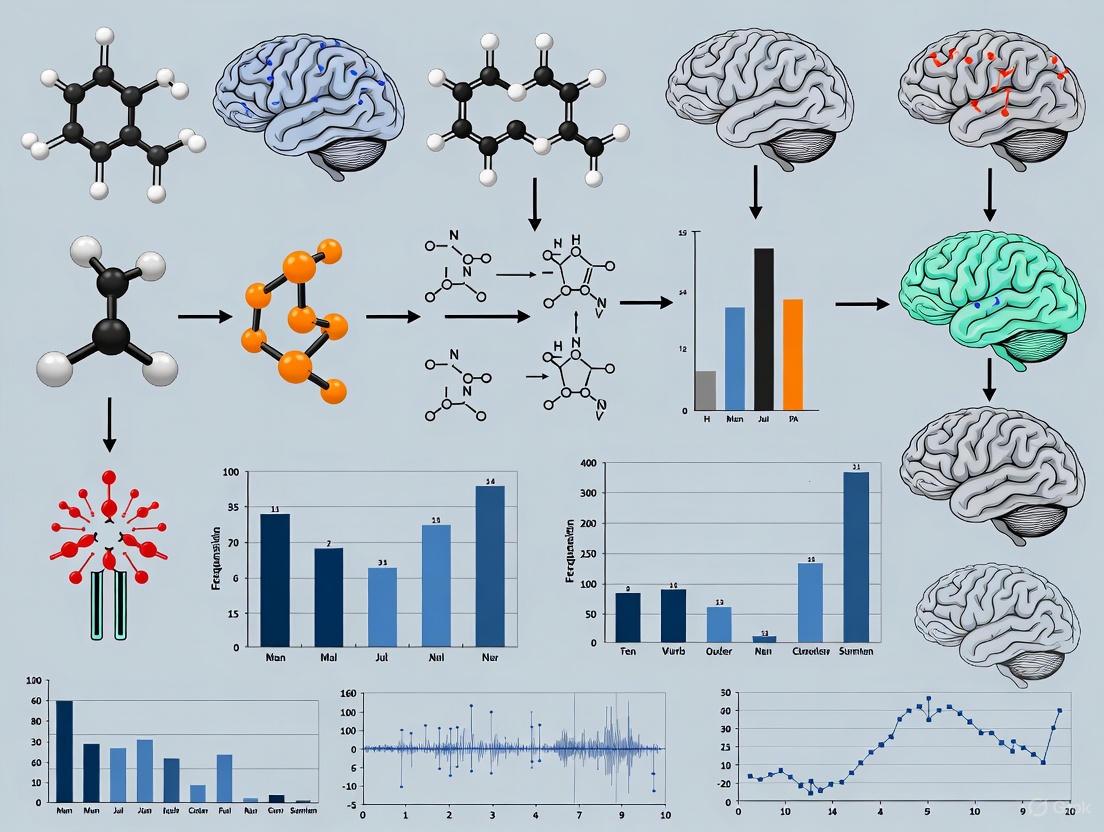

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for a VR clinical trial.

Detailed Protocol Breakdown

1. Participant Recruitment and Screening:

- Population: The study should clearly define the target patient population (e.g., post-stroke, traumatic brain injury) [2]. Key demographic and clinical characteristics must be documented.

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: These are established per the PICOS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design). For example, inclusion may be limited to individuals with a specific diagnosis and age range, while exclusion may involve comorbidities or contraindications for VR use [2] [4].

2. Baseline and Outcome Assessment:

- Primary Outcome: Cognitive function is a common primary endpoint, measured using standardized neuropsychological batteries [2] [3].

- Secondary Outcomes: These may include motor function, psychological well-being, quality of life, and neurophysiological or molecular biomarkers of neuroplasticity (e.g., from fMRI, EEG, or molecular imaging) [1].

- Assessment Tools: Validated and reliable tools specific to the research domain must be selected. For instance, the use of advanced tools like ECG, GSR, and EEG in VR color perception studies is still limited, highlighting a potential area for methodological advancement [5].

3. Intervention Protocol:

- VR Intervention Group: Participants engage in structured sessions using VR systems. For example, sessions may involve commercially available sports games (e.g., "Beat Saber," "VR Boxing") or custom-designed rehabilitation tasks. A typical protocol might involve 60-minute sessions, 3-5 times per week, for 8-12 weeks [2]. The intervention should be designed to be progressive, increasing in difficulty to match patient recovery.

- Control Group: The control group typically receives an active control (e.g., conventional physical therapy, cognitive exercises) or a sham intervention to control for non-specific effects like attention and expectation.

- Apparatus: The protocol must specify the VR hardware (e.g., HTC Vive Pro Eye head-mounted display) and software (e.g., environments rendered with Unreal Engine) [6]. Key parameters like session duration, frequency, and total intervention period must be standardized.

Molecular Signaling Pathways in VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

The immersive experience of VR engages specific molecular pathways that lead to synaptic strengthening and structural reorganization. The following diagram maps the key signaling cascades from sensory input to functional output.

Diagram 2: Key molecular pathways in VR-induced neuroplasticity.

Pathway Description: The process begins with the VR stimulus, which provides intense, multi-sensory input and motor challenges. This leads to high-frequency neuronal firing and the activation of NMDA receptors, allowing calcium (Ca²⁺) influx into the postsynaptic neuron. The rise in intracellular Ca²⁺ triggers key signaling enzymes like Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CamKII) and Protein Kinase C (PKC). These kinases activate transcription factors, most notably CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein), which translocates to the nucleus. CREB phosphorylation promotes the expression of neurotrophic factors like Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) [1]. BDNF, through its receptor TrkB, drives the final common pathway of neuroplasticity: synaptic growth and stabilization. This includes synaptogenesis, dendritic arborization, and the long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic circuits, which ultimately manifest as improved motor and cognitive functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully implementing a VR neuroplasticity research program requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. This table details the key components for a comprehensive experimental setup.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for VR Neuroplasticity Studies

| Item | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| HTC Vive Pro Eye | Hardware | A head-mounted display (HMD) with integrated eye-tracking, used to deliver immersive VR environments and monitor user gaze [6]. |

| Unreal Engine (v4.27+) | Software | A real-time 3D creation tool for building highly realistic and interactive virtual environments for experiments and interventions [6]. |

| 3D Modeling Software (e.g., Autodesk 3ds Max) | Software | Used to create detailed 3D models of objects and scenes (e.g., forest, office) that are imported into the game engine [6]. |

| fMRI / fNIRS | Measurement Tool | Non-invasive neuroimaging techniques to measure brain activity and hemodynamic changes correlated with VR tasks and plastic reorganization. |

| BDNF Assay Kits | Biochemical Reagent | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to quantify BDNF protein levels in serum or plasma as a molecular biomarker of neuroplasticity. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | Methodology | A standardized tool for assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias in randomized controlled trials included in systematic reviews [2]. |

| Molecular Imaging Probes | Biochemical Reagent | Radioactive or fluorescent tracers used with PET or two-photon microscopy to visualize synaptic density or specific neurotransmitter systems in vivo [1]. |

VR technology represents a paradigm shift in modulating neuroplasticity for therapeutic benefit. The evidence from meta-analyses confirms its significant positive effects on cognitive and motor functions in neurologically impaired populations. The underlying efficacy is driven by a coordinated set of mechanisms: immersive environments that provide enriched sensory input, interactive tasks that drive motor and cognitive learning, and engaging formats that boost motivation and adherence. At the molecular level, these experiences engage well-defined signaling pathways, culminating in the expression of neurotrophins like BDNF and the subsequent stabilization of new synaptic connections. Future research, leveraging advanced molecular imaging and computational modeling integrated with VR, is poised to further personalize interventions and unlock precise, targeted treatments for neurological disorders, solidifying VR's role as an indispensable tool in clinical neuroscience and neurorehabilitation.

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) and Electroencephalography (EEG) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for investigating brain dynamics within controlled yet ecologically valid environments. This synergy is particularly relevant for exploring how social and cognitive stimuli modulate fundamental neural rhythms, offering unprecedented insights into the brain's functional mechanisms. Research demonstrates that social stimuli in VR significantly modulate alpha wave (8-12 Hz) activity, suggesting a unique neural signature for immersive social interactions [7] [8]. Concurrently, theta oscillations (4-7 Hz) have been identified as traveling waves that propagate across the cortex, forming a fundamental mechanism for large-scale neural coordination during cognitive tasks [9]. Understanding the dynamics of these oscillations is crucial, as studies using hyperscanning techniques reveal that inter-brain synchrony in theta and alpha bands occurs in VR at levels comparable to real-world settings and is positively correlated with collaborative task performance [10]. These findings frame a compelling thesis: VR environments, mediated by precise EEG measurement, provide a unique window into the oscillatory mechanisms that support complex brain functions, from basic sensory processing to high-level social cognition.

Theoretical Foundations of Alpha and Theta Oscillations

Alpha and theta rhythms represent two of the most prominent and studied oscillatory activities in the human brain. Their dynamics provide a window into the brain's functional state during both rest and cognitive engagement.

Alpha Rhythms: Functional Roles and Characteristics

Alpha oscillations (8–12 Hz) are traditionally associated with a brain idling state, but contemporary research attributes to them a more active role in sensory inhibition and internal cognitive processing. A key characteristic of these rhythms, revealed through direct cortical recordings, is their nature as traveling waves that propagate across the cortical surface at speeds of approximately 0.25–0.75 m/s [9]. This propagation suggests a mechanism for organizing neural processing across space and time. In the context of VR, alpha activity demonstrates significant modulation by social stimuli. Studies comparing Face-to-Face, Online, and VR educational settings found that the VR environment uniquely and significantly influenced alpha wave patterns, indicating that immersive social stimuli can directly alter this fundamental rhythm [7] [8].

Theta Rhythms: Functional Roles and Characteristics

Theta oscillations (4–7 Hz) are strongly linked to working memory, spatial navigation, and sustained attention. Like alpha waves, theta oscillations also manifest as large-scale traveling waves, forming contiguous clusters of cortex oscillating at the same frequency [9]. This spatial coherence is behaviorally relevant; the consistency of theta wave propagation correlates with successful task performance, and these waves are more consistent when subjects perform well [9]. In collaborative VR tasks, theta synchrony between individuals' brains (inter-brain synchrony) has been identified as a key predictor of team performance, highlighting its role in social coordination [10].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Alpha and Theta Oscillations

| Feature | Alpha Oscillations (8-12 Hz) | Theta Oscillations (4-7 Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functional Roles | Sensory inhibition, internal cognitive processing [11] | Working memory, spatial navigation, sustained attention [9] |

| Spatial Dynamics | Traveling waves propagating at ~0.25-0.75 m/s [9] | Traveling waves forming spatially contiguous clusters [9] |

| Modulation by VR | Significant influence by social stimuli in VR environments [7] | Correlated with collaborative task performance in VR [10] |

| Behavioral Correlation | --- | Propagation consistency correlates with task performance [9] |

Experimental Methodologies in VR-EEG Research

Investigating oscillatory dynamics in VR requires carefully controlled experimental designs that balance ecological validity with methodological rigor. The following protocols represent prevalent approaches in the field.

Protocol 1: Social Stimulus Observation in Educational Environments

This ecological experiment was designed to capture authentic neural mechanisms during social interaction across three distinct educational settings [7].

- Participants: 27 student volunteers (mean age 19.9 years) with no history of neurological diseases.

- Stimuli and Design: The experiment collected EEG data from student pairs in three educational environments: Face-to-Face (FF), Virtual Reality (VR), and Online (ONL). The core task involved participants opening their eyes upon instruction and making initial eye contact with a real social stimulus (another person) presented in each environment. Data capture focused on the first seven seconds of this social observation.

- EEG Acquisition: Brain wave data was collected using a portable Emotiv Insight 2.0 headset, confirming no interference with the VR headset. The study emphasized the importance of portable EEG devices for studying brain activity in diverse, naturalistic learning settings [7].

- Data Analysis: Analysis focused on Alpha (8–12 Hz) and Theta (4–7 Hz) frequency bands. Statistical comparisons were made across the three environmental conditions to identify significant modulations induced by the social stimulus.

Protocol 2: Collaborative Visual Search with Hyperscanning

This protocol examines inter-brain synchrony during a joint attention task, comparing VR to real-world settings [10].

- Participants: Pairs of participants engaged in a collaborative task.

- Stimuli and Design: A collaborative visual search task was performed in both VR and a real-world (RW) environment. This design allowed for direct comparison of neural synchrony across physical and virtual settings.

- EEG Acquisition: EEG hyperscanning was employed, which involves the simultaneous recording of neural activity from two or more interacting individuals. This technique is crucial for capturing the dynamics of brain-to-brain coordination during social tasks.

- Data Analysis: Inter-brain synchronization (IBS) was quantified, particularly in the theta and alpha bands. The phase locking value (PLV) was used to assess synchrony between brain regions of interacting partners. Correlation analysis between IBS and task performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, response time) was conducted.

Protocol 3: Identifying Traveling Waves During a Memory Task

This methodology utilizes high-resolution cortical recordings to characterize the spatiotemporal dynamics of oscillations [9].

- Participants: 77 neurosurgical patients undergoing direct electrocorticographic (ECoG) monitoring.

- Stimuli and Design: Participants performed a Sternberg working-memory task, which is known to elicit large-amplitude oscillations related to memory.

- EEG Acquisition: Direct electrocorticographic (ECoG) recordings from the cortical surface provided high-fidelity neural signals.

- Data Analysis: A specific analytical framework identified traveling waves at the single-trial level. The process involved:

- Identifying narrowband oscillatory peaks in the power spectrum.

- Clustering contiguous electrodes showing oscillations at a similar frequency ("oscillation clusters").

- Using a circular-linear model to characterize the relationship between electrode position and oscillation phase, quantifying the phase-gradient directionality (PGD) as a measure of wave robustness.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of a typical VR-EEG experiment, from setup to data interpretation:

Key Findings and Quantitative Data Synthesis

Empirical studies have yielded substantial quantitative data on how VR environments modulate alpha and theta oscillations. The tables below synthesize key findings for clear comparison.

Alpha and Theta Modulation by VR and Social Stimuli

Table 2: Modulation of Alpha and Theta Waves by Social Stimuli in VR

| Experimental Condition | Effect on Alpha Waves (8-12 Hz) | Effect on Theta Waves (4-7 Hz) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Reality (VR) Social Stimulus | Significant modulation by social stimuli [7] [8] | --- | [7] [8] |

| Face-to-Face (FF) Social Stimulus | --- | --- | [7] |

| Online (ONL) Social Stimulus | --- | --- | [7] |

| VR vs. Real-World (Collaborative Search) | IBS in alpha band occurs, though may lag behind real-world [10] | IBS occurs at levels comparable to real-world [10] | [10] |

| Memory Task (General) | Traveling waves propagate at ~0.25-0.75 m/s [9] | Traveling waves propagate at ~0.25-0.75 m/s [9] | [9] |

Machine Learning Classification of VR-Induced EEG Signals

Research has successfully used machine learning to classify EEG signals from different VR conditions, highlighting distinct neural responses.

Table 3: Machine Learning Classification of EEG in 2D vs. 3D VR

| Feature Extraction Method | Machine Learning Algorithm | Reported Classification Accuracy | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | Random Forest (RF) | 95.02% | CSP features outperformed PSD features [12] |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | 93.16% | CSP features outperformed PSD features [12] |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 91.39% | CSP features outperformed PSD features [12] |

| Power Spectral Density (PSD) | Various | Lower than CSP | Inferior to CSP for classifying VR conditions [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details critical hardware, software, and analytical tools employed in contemporary VR-EEG research, as evidenced by the reviewed studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for VR-EEG Studies

| Tool Name / Category | Specification / Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Portable EEG Headset (e.g., Emotiv Insight 2.0) | Hardware | Enables EEG data collection in naturalistic and immersive settings without constraining movement [7]. |

| VR Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Hardware | Presents immersive, controlled visual and auditory stimuli to create the virtual environment. |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) | Hardware | Provides high-fidelity, direct cortical recordings from the surface of the brain, used for detailed analysis of traveling waves [9]. |

| Hyperscanning Setup | Hardware/Software | Allows simultaneous EEG recording from multiple interacting brains to study inter-brain synchrony during social tasks [10]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | Algorithm | A feature extraction method that effectively identifies spatial patterns in EEG signals to discriminate between mental states (e.g., 2D vs. 3D VR) [12]. |

| Phase Locking Value (PLV) | Algorithm | Quantifies the synchronization between two neural signals or between brains (IBS) by measuring the consistency of their phase difference [10]. |

| Phase-Gradient Directionality (PGD) | Algorithm | A metric used to identify and quantify the robustness of traveling waves from multi-electrode recordings [9]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | Algorithm | A machine learning algorithm demonstrated to achieve high accuracy (>95%) in classifying EEG signals from different VR conditions [12]. |

Signaling Pathways and Neural Dynamics

The neural mechanisms underlying alpha and theta oscillations can be conceptualized as a complex system of interacting functional pathways. The following diagram synthesizes the core processes involved in the generation, propagation, and functional impact of these rhythms, particularly in the context of VR tasks.

This model illustrates the cascading processes from stimulus presentation to behavioral outcome. VR stimuli induce and modulate theta and alpha rhythms, which manifest as propagating traveling waves across the cortex. These coordinated oscillatory patterns support large-scale brain connectivity and facilitate inter-brain synchrony during social interactions. The ultimate functional consequences are enhanced cognitive processes and improved behavioral performance, which are measurable correlates of the underlying oscillatory dynamics.

The confluence of VR and EEG technologies has fundamentally advanced our capacity to investigate brain oscillations within complex, simulated environments. The evidence synthesized in this review firmly supports the thesis that alpha and theta wave dynamics are central mechanisms by which the brain orchestrates cognitive and social functions. Key findings demonstrate that social stimuli within VR significantly modulate alpha activity, that theta and alpha oscillations propagate as traveling waves to coordinate neural activity across widespread cortical networks, and that the synchrony of these rhythms between individuals is a robust predictor of collaborative success. The application of sophisticated machine learning algorithms to classify these neural signals further underscores their reliability and functional significance. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of experimental protocols, analytical techniques, and neurotechnological tools—guided by initiatives such as the BRAIN Initiative [13]—will undoubtedly yield deeper, more transformative insights into the oscillatory foundations of the human mind, with profound implications for education, therapy, and human-computer interaction.

Emerging research in immersive virtual reality (IVR) demonstrates that the human brain processes virtual experiences with a remarkable degree of realism, primarily through mechanisms of embodied simulation. This whitepaper synthesizes current neuroscientific and cognitive research to elucidate the core principles of this phenomenon. We examine how IVR-triggered sensorimotor contingencies activate neural networks associated with body ownership, agency, and self-location, creating a powerful sense of embodiment that the brain treats as functionally real. Framed within broader thesis research on brain activity during IVR tasks, this guide details quantitative findings, experimental protocols for electroencephalography (EEG), and key applications in scientific and clinical domains, including drug development.

Theoretical Framework: The Neuroscience of Embodiment

Embodied simulation in IVR is not a singular cognitive event but a multifaceted perceptual state constructed by the brain. It hinges on the integration of three core components: the Sense of Body Ownership (the feeling that a virtual body is one's own), the Sense of Agency (the feeling of controlling the virtual body's actions), and the Sense of Self-Location (the feeling of being located inside the virtual body) [14]. The underlying neural mechanisms are best understood through the lens of embodied cognition, which posits that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body's interactions with the world [15].

Wilson's (2002) six principles of embodied cognition provide a robust framework for understanding how IVR-mediated environments facilitate this realistic experience [15]:

- Cognition is Situated: Cognition occurs in the context of a real-world environment. In IVR, the virtual environment becomes the "situated" context for the user's cognitive processes.

- Cognition is Time-Pressured: Cognition must be understood in terms of how it functions under the pressures of real-time interaction with the environment, a core feature of IVR's real-time rendering.

- We Offload Cognitive Work onto the Environment: The brain uses the environment to reduce cognitive load. In IVR, users leverage the virtual space as an external memory and a tool for problem-solving, such as using virtual brushstrokes in Tilt Brush as extensions of their cognitive-motor system [15].

- The Environment is Part of the Cognitive System: The coupling between the user and the virtual world is so tight that the line between the mind and the environment is blurred, forming a unified cognitive system.

- Cognition is for Action: The function of the mind is to guide action, not just to represent the world. IVR facilitates this through gestural interaction and spatial navigation, which are fundamental to creative thinking and problem-solving [15].

- Offline Cognition is Body-Based: Even when disconnected from the environment, cognitive activities (e.g., mental imagery) are simulations of actual interactions, which IVR directly taps into and externalizes.

This framework explains why the brain treats virtual experiences as real: because the core cognitive and neural systems that process real-world, embodied experiences are the same ones recruited during a compelling IVR session.

Table 1: Core Components of Sense of Embodiment in IVR

| Component | Definition | Example in IVR |

|---|---|---|

| Body Ownership | The feeling that a virtual body or body part is one's own [14]. | Perceiving a virtual hand as one's own during a "virtual rubber hand illusion" task. |

| Agency | The sense of being the cause of and controlling the actions of the virtual body [14]. | Moving a virtual arm and seeing it move congruently with one's own motor command. |

| Self-Location | The feeling of being located inside a virtual body at a specific spatial location in the virtual environment [14]. | Feeling present within a virtual pharmacy or laboratory environment. |

Quantitative Biomarkers and Neurophysiological Data

Electroencephalography (EEG) has emerged as a primary tool for identifying objective, quantitative biomarkers of embodiment in IVR. A scoping review on the topic confirms that EEG can capture measurable neural responses when embodiment is modulated, though the field currently suffers from a lack of standardization [14].

The review, which analyzed 41 articles, found high heterogeneity in both the VR-induced stimulations used to modulate embodiment and in the subsequent EEG data collection, preprocessing, and analysis methods [14]. Despite this, individual studies consistently show that changes in embodiment elicit electrophysiological signatures that can be quantified. Common EEG-derived metrics include event-related potentials (ERPs), changes in spectral power (e.g., in mu, alpha, or beta bands), and measures of functional connectivity between brain regions. A significant challenge is the identification of reliable EEG-based biomarkers for embodiment, as the current marked heterogeneity reflects a lack of consensus on key neural markers [14].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Findings on Embodiment and Associated Brain Activity

| Study Focus / Modulation Technique | Key Quantitative Finding | EEG Metric / Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| General Embodiment Modulation [14] | EEG captures measurable neural responses when embodiment is modulated in VR. | Various EEG-derived metrics (e.g., ERPs, spectral power); correlation with subjective questionnaire data. |

| High-Embodiment VR Tasks [15] | Virtual sculpting tasks prompted gains in spatial reasoning by 27%. | Enacts Wilson's Principle 4 (environment as part of the cognitive system). |

| Spatial Learning (TASC System) [15] | Embodied interaction (gesturing) in IVR enhances spatial reasoning and problem-solving. | Demonstrates situated cognition (Wilson's Principle 1) and action-oriented cognition (Wilson's Principle 5). |

Experimental Protocols for EEG in Embodiment Research

To advance the standardization called for in the literature, the following provides a detailed methodological protocol for a typical experiment investigating the sense of agency using EEG.

Protocol: Measuring Sense of Agency with EEG

1. Objective: To quantify the neural correlates of the sense of agency in an IVR environment by manipulating the congruence between a participant's motor actions and the resulting visual feedback in the virtual world.

2. Experimental Setup and Reagents: The following tools and software are essential for conducting this research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for an EEG-IVR Experiment

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Immersive VR Headset (HMD) | Provides the visual virtual environment and blocks out the real world. Requires head-tracking systems (e.g., HTC Vive, Oculus Rift) [16]. |

| Motion Controllers | Enable user interaction with the virtual environment and tracking of hand/arm movements [16]. |

| High-Density EEG System | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp (e.g., 64-channel or 128-channel system). |

| EEG Amplifier & Recording Software | Amplifies and digitizes the neural signals for offline analysis. |

| VR Development Platform | Used to create the custom virtual environment and experimental task (e.g., Unity 3D with SteamVR plugin). |

| Sync Box / Trigger Interface | Sends precise timing triggers from the VR computer to the EEG amplifier to synchronize brain data with virtual events. |

| Validated Embodiment Questionnaire | Collects subjective data on the participant's experience of body ownership, agency, and self-location for correlation with EEG data [14]. |

3. Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Fit the participant with the EEG cap according to standard 10-20 system placement. Apply electrolyte gel to achieve impedances below 5 kΩ. Subsequently, calibrate the VR headset and motion controllers for the participant.

- Task Design (Within-Subjects): Participants perform a simple task, such as pressing a virtual button, under three conditions in a randomized order:

- Congruent Condition: The virtual hand moves instantly and precisely in sync with the participant's actual hand movement.

- Incongruent Condition (Spatial Delay): The movement of the virtual hand is spatially offset or distorted from the participant's actual movement trajectory.

- Incongruent Condition (Temporal Delay): The movement of the virtual hand is delayed by 150-500 ms relative to the participant's actual movement.

- EEG Recording: The experiment is divided into blocks of trials. Each trial begins with a fixation cross, followed by an auditory cue to initiate the movement. The EEG is recorded continuously throughout the experiment. Synchronization triggers marking the onset of the cue and the virtual hand movement are sent from the VR software to the EEG amplifier.

- Subjective Measures: After each block, participants rate their sense of agency (e.g., "To what extent did you feel you were controlling the virtual hand?") on a visual analog scale. A more comprehensive embodiment questionnaire is administered at the end of the entire session.

4. Data Analysis:

- EEG Preprocessing: Process the raw EEG data to remove artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity, line noise) using tools like EEGLAB or MNE-Python.

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): Time-lock the EEG data to the onset of the participant's motor action or the virtual hand movement. Compare the amplitude and latency of ERP components (e.g., N200, P300) between the congruent and incongruent conditions.

- Spectral Analysis: Calculate the power in specific frequency bands (e.g., mu-band 8-13 Hz suppression as an index of motor cortex activation) during the movement execution and feedback phases across conditions.

- Statistical Analysis: Use repeated-measures ANOVA to test for significant differences in EEG metrics and subjective ratings between the three experimental conditions.

Diagram 1: EEG-IVR Agency Experiment Workflow

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The understanding that the brain treats virtual experiences as real opens up transformative applications in pharmaceutical research and development. The principle of distraction, facilitated by IVR's ability to fully occupy finite attentional resources, is a key mechanism, particularly in pain management [16].

Pain Management and Analgesic Efficacy: Clinical research has demonstrated that IVR is an effective non-pharmacologic adjunct to standard analgesic treatments [16]. A review of seven studies found that five showed VR reduces pain, distress, and anxiety in both adult and pediatric patients undergoing unpleasant medical procedures like burn wound care [16]. One randomized trial showed that VR combined with analgesics was significantly more effective in reducing procedural pain in children than analgesics alone [16]. The mechanism is attributed to IVR's immersive quality "hijacking" auditory, visual, and proprioceptive senses, leaving less cognitive capacity available for processing pain signals [16].

Molecular Visualization and Drug Design: IVR and Augmented Reality (AR) allow researchers and healthcare professionals to step inside and manipulate 3D molecular structures. This embodied interaction with a drug target or protein can enhance intuition and understanding of structure-activity relationships in a way that 2D screens cannot, accelerating the drug discovery process [17].

HCP Training and Empathy Building: VR simulations are used to train healthcare professionals (HCPs) on complex medical devices or procedures in a risk-free setting [17]. Furthermore, VR is deployed for empathy building, allowing HCPs to "step into the shoes" of patients suffering from conditions like Parkinson's disease, fostering a deeper understanding that can improve patient care [17].

Diagram 2: IVR Pharma Apps and Mechanisms

Methodological Challenges and Future Directions

While the potential is vast, the field must overcome significant methodological hurdles to mature. The scoping review by [14] identified a high heterogeneity in VR-induced stimulations, EEG data collection protocols, preprocessing pipelines, and analysis techniques. This lack of standardization is compounded by the common use of non-validated, non-standardized questionnaires for collecting subjective embodiment data [14]. This heterogeneity currently prevents the direct comparison of results across studies and the establishment of universally accepted neural biomarkers of embodiment.

Another critical challenge is the immateriality paradox. High levels of embodiment in IVR can lead to significant gains in spatial reasoning (e.g., 27% in virtual sculpting), but this often comes at the cost of what is termed haptic dissonance—a cognitive disruption caused by the mismatch between expected and actual tactile feedback [15]. For instance, one study noted that 68% of ceramics students using IVR had trouble perceiving material properties, a violation of the real-time sensorimotor alignment emphasized in embodied cognition theory [15].

Future research must prioritize:

- Standardization: Developing consensus on experimental designs, EEG metrics, and validated subjective scales for embodiment [14].

- Advanced Haptics: Investing in technology that mitigates haptic dissonance to provide more congruent multisensory feedback.

- Ethical Frameworks: Guiding the ethical use of IVR, especially in clinical populations, given its potent ability to manipulate perceptual reality [15].

In the evolving landscape of cognitive neuroscience, immersive Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating brain function. Unlike traditional stimuli, VR's capacity to deliver multi-sensory, ecologically valid experiences engages distinct and robust neural mechanisms. This technical guide examines three core brain systems—the Medial Prefrontal Cortex (MPFC), the Mirror Neuron System (MNS), and Sensory Integration Hubs—that are critically activated during VR tasks. Framed within broader thesis research on brain activity in immersive environments, this whitepaper synthesizes current neurophysiological evidence, details experimental protocols, and provides a toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to leverage VR for neurological research and therapeutic development.

Neurobiological Foundations of VR Engagement

The brain's response to immersive VR is not merely an amplified version of its response to traditional media. The illusion of presence and embodiment within a virtual environment triggers specific and synergistic interactions between key neural systems involved in self-referential processing, action perception, and multi-sensory integration.

The Medial Prefrontal Cortex (MPFC)

The MPFC is a central node in the default mode network and is critically involved in self-referential thought, emotional regulation, and assigning personal significance to experiences. Its activation is modulated by the subjective sense of presence in a VR environment.

- Function in VR: In VR, the MPFC shows distinct activation patterns linked to the first-person perspective (1PP). Studies indicate that adopting a 1PP in VR, which enhances the feeling of "being there" and ownership over virtual actions, significantly engages the MPFC [18]. This engagement is crucial for the emotional and cognitive components of presence.

- Role in Neurorehabilitation: The MPFC's interaction with the brain's reward system, particularly dopamine pathways, is a key target for VR-based therapies. For chronic pain management, designing VR experiences that activate the MPFC can help restore its diminished functionality, thereby promoting pain relief [19]. Furthermore, in exposure therapy for phobias, the MPFC, along with the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), exhibits a normalization of activity over successive VR sessions, correlating with the inhibition of fear responses [20].

Table 1: Key Findings on the MPFC in VR Studies

| Function | VR Context | Activation Pattern | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Referential Processing | First-Person Perspective (1PP) | Increased Activation [18] | Critical for designing for embodiment and presence |

| Fear Inhibition / Emotional Regulation | Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) | Normalized activity over sessions [20] | Biomarker for therapeutic efficacy in anxiety disorders |

| Chronic Pain Modulation | VR Pain Relief | Associated with reward system (dopamine) [19] | Target for non-pharmacological analgesic interventions |

The Mirror Neuron System (MNS)

The MNS, primarily located in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), ventral premotor cortex (PMv), and inferior parietal lobule (IPL), is activated both when an individual performs an action and when they observe a similar action performed by another. VR is uniquely positioned to manipulate and enhance MNS engagement.

- Core Components: The human MNS is a parietofrontal network. Its core regions include the IFG (Brodmann area 44/45), the dorsal and ventral premotor cortex (BA6), and the inferior parietal lobule (BA40) [21] [18].

- Enhancement through VR: Research demonstrates that observing actions from a first-person perspective in an immersive VR environment leads to stronger MNS activation compared to a third-person perspective. This is measured through increased event-related potentials (ERPs) and greater suppression of sensorimotor mu (α) rhythms in EEG, indicating heightened cortical excitability [18]. Furthermore, paradigms that combine motor imagery (MI) with the observation of congruent virtual arm movements (e.g., in a VR-based rowing task) recruit the MNS more effectively than conventional MI tasks, also engaging additional visual and parietal areas [22].

- Functional Connectivity: A critical finding is that VR-based action observation from a 1PP not only activates the MNS but also strengthens its functional connectivity with the primary sensorimotor cortex. This functional integration is a proposed neural mechanism through which VR facilitates motor recovery in neurorehabilitation [18].

Sensory Integration Hubs

For a VR experience to feel seamless and real, the brain must successfully integrate visual, auditory, and somatosensory signals. This process occurs in a hierarchical manner across a network of sensory integration hubs.

- Cortical Hierarchy: Sensory processing follows a gradient from unimodal primary sensory areas to transmodal association cortices. A quantitative framework using "sensory magnitude" (the variance in brain activity explained by primary visual, auditory, and somatosensory signals) and "sensory angle" (the proportional contribution of each modality) can map this integration. Areas higher in the cortical hierarchy exhibit lower sensory magnitude, indicating more abstract, multisensory representations [23].

- The Action Observation Network (AON): This network, which overlaps with the MNS, robustly encodes action-related information across different sensory modalities (visual, auditory, and combined audiovisual). Neural representations of actions within the AON are stable, with features like "Effector" (e.g., hand, foot) and "Social" domains being particularly dominant [24].

- Superior Colliculus and Multisensory Cells: Subcortical structures like the superior colliculus contain multisensory cells that integrate visual and auditory cues to optimize responses to the environment. VR rehabilitation strategies, such as Audio-Visual Scanning Training (AViST), leverage these pathways to improve spatial awareness in individuals with visual field defects [25].

Figure 1: Neural Mechanisms of VR. This diagram illustrates how different components of a VR stimulus engage distinct but interacting brain systems, which synergistically contribute to therapeutic outcomes.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

To reliably measure activation in the MPFC, MNS, and sensory hubs, researchers employ a suite of neuroimaging techniques alongside carefully designed VR paradigms.

Protocol 1: EEG Investigation of MNS-Sensorimotor Integration

This protocol quantifies functional connectivity between the MNS and sensorimotor cortex during action observation in VR [18].

- Objective: To determine if the first-person perspective (1PP) in VR enhances functional integration between the MNS and sensorimotor cortex compared to a third-person perspective (3PP).

- Participants: Healthy adults.

- VR Task: Participants observe goal-directed hand actions (e.g., grasping a virtual object) from either a 1PP or 3PP in a randomized, counter-balanced design.

- Data Acquisition: High-density Electroencephalography (EEG) is recorded throughout the task.

- Data Analysis:

- Source Localization: The exact Low-Resolution Brain Electrophysiological Tomography (eLORETA) software is used to estimate the cortical sources of the EEG signals.

- Time-Frequency Analysis: Event-Related Spectral Perturbation (ERSP) is calculated, focusing on the α1 (8-10 Hz) and α2 (10-12 Hz) frequency bands over sensorimotor areas (mu rhythm suppression).

- Functional Connectivity: Lagged Phase Synchronization (LPS) is computed between the core MNS regions (IFG, PMv, IPL) and the primary sensorimotor cortex.

- Key Outcome Measures: Significantly greater mu suppression and enhanced LPS between the MNS and sensorimotor cortex in the 1PP condition versus the 3PP condition.

Protocol 2: fMRI Mapping of an Ecologically-Valid MI-MO Task

This protocol uses fMRI to compare brain activation during a VR-based Motor Imagery and Motor Observation (MI-MO) task against a conventional task [22].

- Objective: To map the brain networks activated by an ecologically-valid VR task that combines MI and MO and compare it to a standard MI task.

- Participants: Healthy, right-handed adults screened for motor imagery ability.

- Tasks:

- Experimental (NeuRow): In an fMRI-compatible VR headset, participants imagine rowing with their left or right arm while observing the congruent movement of a virtual avatar's arm from a 1PP.

- Control (Graz BCI): Participants perform kinesthetic motor imagery of hand movements without congruent visual feedback.

- Data Acquisition: Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signals are acquired via a 3T fMRI scanner.

- Data Analysis: General Linear Model (GLM) analysis is used to identify task-related activation. Contrasts are defined as

[NeuRow > Graz BCI]and[NeuRow > Motor Execution]. - Key Outcome Measures: The NeuRow task is expected to elicit significantly stronger activation in a widespread network including the somatomotor and premotor cortices, parietal and occipital lobes, and the MNS.

Table 2: Comparison of Key VR Neuroimaging Protocols

| Parameter | EEG Protocol for MNS [18] | fMRI Protocol for MI-MO [22] |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Measure functional connectivity & cortical rhythm modulation | Map whole-brain activation from an ecologically-valid task |

| Key Technique | eLORETA source localization & Lagged Phase Synchronization | BOLD fMRI & GLM analysis |

| VR Paradigm | Action Observation (1PP vs. 3PP) | Combined Motor Imagery + Motor Observation (NeuRow) |

| Primary Brain Regions of Interest | MNS (IFG, PMv, IPL) & Sensorimotor Cortex | MNS, Somatomotor Cortex, Parieto-occipital areas |

| Key Metrics | Mu (α) suppression, Functional Connectivity (LPS) | BOLD signal change, Activation cluster size & significance |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential tools and methodologies for conducting research on brain activation via immersive VR.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG with eLORETA | Provides millisecond-level temporal resolution to study neural dynamics and functional connectivity between cortical regions. | Analyzing the time-course of MNS-sensorimotor integration during VR action observation [18]. |

| fMRI-Compatible VR Systems | Allows for precise spatial mapping of whole-brain BOLD signals while participants are immersed in a controlled virtual environment. | Comparing neural networks activated by ecologically-valid VR tasks vs. conventional paradigms [22]. |

| fNIRS with Immersive Projection | Enables mobile, ecologically-valid measurement of cortical hemodynamics (e.g., in PFC) during movement-based VR therapy. | Monitoring within-session prefrontal cortex response during VR Exposure Therapy for phobias [20]. |

| Multisensory Integration Model (Sensory Magnitude/Angle) | A quantitative framework for analyzing fMRI data to characterize how a brain region integrates information from different sensory modalities. | Mapping the hierarchical transition from unimodal to transmodal cortical processing during naturalistic movie-watching or VR [23]. |

| Spatial Audio & 3D Laser Scanning | Creates highly realistic and acoustically accurate virtual environments to study multisensory integration in a controlled yet ecologically-valid setting. | Constructing a virtual replica of a real-world concert hall to study audio-visual integration in typical and clinical populations [26]. |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow. A generalized workflow for designing a VR neuroimaging study, from selecting a tool matched to the question to data interpretation.

The targeted activation of the MPFC, Mirror Neuron System, and sensory integration hubs forms the foundational neurobiological rationale for using immersive VR in cognitive research and therapeutic development. The MPFC underpins the subjective experience of presence and emotional engagement, the MNS facilitates motor learning and simulation through its response to embodied perspectives, and distributed sensory hubs create a coherent, multi-sensory perception of the virtual world. The experimental protocols and tools detailed herein provide a roadmap for researchers to rigorously investigate these systems. As VR technology advances, a deepened understanding of these key brain regions will undoubtedly unlock more precise and effective applications in neurology, psychiatry, and neurorehabilitation.

The integration of virtual reality (VR) in neuroscience research provides a powerful tool for investigating and harnessing neuroplasticity—the brain's remarkable capacity to reorganize its structure and function in response to experience. This whitepaper examines the molecular and circuit-level mechanisms through which immersive VR experiences translate sensory input into synaptic change. By creating controlled, multi-sensory environments that closely mimic real-world scenarios, VR engages dopaminergic and oxytocinergic systems that reinforce learning and emotional engagement. Furthermore, when combined with brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), VR enables real-time monitoring and modulation of neural activity, creating closed-loop systems that optimize therapeutic outcomes and cognitive enhancement. This synthesis of evidence highlights VR's transformative potential in clinical rehabilitation, treatment of anxiety disorders, and educational applications, while outlining specific molecular pathways and experimental protocols for researchers investigating immersive technologies.

Virtual reality represents a paradigm shift in how researchers can investigate experience-dependent neuroplasticity. Unlike traditional laboratory tasks, VR immerses users in computer-generated environments that simulate real-world experiences while allowing for precise manipulation of sensory inputs and cognitive demands [27]. This capability for ecological validity combined with experimental control makes VR particularly valuable for studying the molecular correlates of learning in both healthy and impaired neural systems.

The brain's plastic capabilities encompass a broad spectrum of mechanisms, including synaptic plasticity, dendritic remodeling, and changes in neural connectivity, all contributing to its dynamic capacity for reorganization [27]. VR interventions leverage these mechanisms by providing rich, interactive sensory experiences that engage multiple neural systems simultaneously. Within the context of a broader thesis on brain activity during immersive tasks, this whitepaper establishes a direct connection between VR-induced sensory input and the synaptic changes that constitute the biological basis of learning, with particular relevance for researchers exploring novel approaches to cognitive enhancement and neurological rehabilitation.

Molecular Mechanisms of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

Neuromodulatory Systems Engaged During Immersive Experience

VR experiences trigger distinct neurochemical responses that facilitate learning and memory consolidation. Research measuring neurologic Immersion—a convolved neurophysiologic measure capturing the value the brain assigns to experiences—has demonstrated that immersive VR generates approximately 60% more neurologic value compared to equivalent 2D experiences [28]. This Immersion metric convolves physiological signals associated with dopamine binding in the prefrontal cortex (linked to attention) and oxytocin release from the brainstem (linked to emotional resonance) [28]. These neurochemical events create optimal conditions for synaptic modification by reinforcing meaningful experiences and enhancing emotional engagement with the virtual content.

The serotonergic system, particularly 5-HT2A receptors, plays a crucial role in modulating sensory gain control during immersive experiences. Optogenetic studies in mouse visual cortex demonstrate that 5-HT2A receptor activation produces divisive gain modulation of sensory input without affecting ongoing baseline activity levels [29]. This mechanism allows the brain to selectively enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of behaviorally relevant sensory information during VR exposure, focusing neural resources on salient environmental features. Specifically, 5-HT2A receptor activation in parvalbumin (PV) interneurons suppresses excitatory neuron responses to visual stimuli while leaving spontaneous activity unchanged, effectively controlling the gain of sensory input through polysynaptic circuit mechanisms [29].

Sensory Processing and Multisensory Integration Pathways

VR uniquely engages multiple sensory modalities simultaneously, creating coordinated patterns of neural activation across distributed brain regions. This multisensory integration triggers synergistic effects on plasticity mechanisms that exceed the impact of unimodal stimulation. The molecular correlates of this enhanced integration include:

- NMDA receptor activation: Critical for long-term potentiation (LTP) in sensory cortices when visual, auditory, and haptic inputs are temporally aligned during VR experiences.

- BDNF release: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression increases in response to enriched environmental stimulation, promoting synaptic growth and stabilization in neural circuits activated by multi-sensory VR.

- Homeostatic scaling mechanisms: VR-induced changes in sensory input drive uniform scaling of synaptic strengths to maintain network stability while allowing for experience-dependent reorganization.

Table 1: Key Molecular Correlates of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

| Molecular Element | Function in VR-Induced Plasticity | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Signals the value of VR experiences; reinforces learning through corticostriatal circuits | Increased neurologic Immersion metrics during compelling VR narratives [28] |

| Oxytocin | Enhances emotional resonance and social learning in interactive VR environments | Correlation with prosocial behaviors following immersive patient journey experiences [28] |

| 5-HT2A Receptors | Modulate sensory gain control in visual cortex; regulate signal-to-noise ratio | Optogenetic activation in PV neurons reduces visual response gain in excitatory neurons [29] |

| BDNF | Promotes synaptic growth and stabilization in circuits activated by multi-sensory VR | Elevated in enriched environmental stimulation; inferred from VR's enhanced effectiveness [27] |

| NMDA Receptors | Mediate long-term potentiation in sensory cortices during aligned multi-sensory inputs | Fundamental mechanism of synaptic plasticity engaged by VR's immersive properties [27] |

Quantitative Assessment of VR-Induced Neural Changes

Neurologic Immersion and Behavioral Correlates

Research with nursing students (n=70) experiencing a patient journey through chronic illness demonstrated that VR generated significantly higher neurologic Immersion compared to 2D video presentation (+60%) [28]. This enhanced Immersion directly translated to behavioral outcomes, with the VR group showing significantly greater willingness to volunteer to help other students—a measure of prosocial behavior motivated by empathic concern [28]. The correlation between Immersion metrics and observable behaviors provides a quantitative framework for assessing the efficacy of VR experiences in driving meaningful neural and behavioral changes.

The Immersion platform produces a 1 Hz data stream by applying algorithms to photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors, measuring a convolved signal that combines attention (dopamine-related) and emotional resonance (oxytocin-related) components [28]. Analysis uses both average Immersion during instruction and a derived variable called Peak Immersion, which cumulates the most valuable parts of the experience by summing peaks above a threshold defined as the median Immersion plus 0.5 standard deviations for each participant [28]. This Peak Immersion variable proves to be a more accurate predictor of behavior than average Immersion, as the brain naturally seeks to return to baseline during extended experiences.

BCI-Enhanced VR for Targeted Neuroplasticity

The combination of VR with brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) creates closed-loop systems that dynamically adapt to the user's neural activity in real time, optimizing interventions for rehabilitation and cognitive enhancement [27]. In motor rehabilitation after stroke, BCIs detect motor intention signals and translate them into movements of a robotic limb or virtual avatar, providing immediate feedback that reinforces the neural pathways involved in motor control [27]. This approach accelerates recovery by continuously adapting the rehabilitation process to the patient's neural responses, creating a personalized training regimen based on real-time neurophysiological data.

For anxiety and phobia treatment, BCIs monitor neural markers of anxiety and modulate VR environments in real time to help patients confront and manage their fears in a controlled setting [27]. This closed-loop system provides tailored exposures adjusted based on neural feedback, promoting long-lasting neural adaptations that reduce anxiety symptoms more effectively than standard exposure therapy [27]. The molecular correlates of these interventions include changes in amygdala reactivity and enhanced prefrontal regulation of emotional responses, reflecting synaptic-level changes in critical fear circuits.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of VR and VR-BCI Interventions

| Intervention Type | Neural Changes | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| VR for Education | 60% increase in neurologic Immersion; increased oxytocin and dopamine signaling | Enhanced empathy; increased helping behaviors; improved information retention [28] |

| VR-BCI for Stroke Rehabilitation | Reorganization of motor cortex; strengthened corticospinal connections | Accelerated recovery of motor function; improved movement accuracy [27] |

| VR-BCI for Anxiety Disorders | Reduced amygdala hyperactivity; enhanced prefrontal-amygdala connectivity | Decreased anxiety symptoms; improved emotion regulation [27] |

| VR for Cognitive Enhancement | Neuroplastic changes in attention networks; modified brain wave frequencies | Improved attention, working memory, and executive function [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating VR-Induced Plasticity

Protocol for Measuring Neurologic Immersion During VR Exposure

Objective: To quantify the neurophysiological correlates of engagement and emotional resonance during VR experiences compared to traditional 2D presentation.

Materials:

- Commercial neurophysiology platform (Immersion Neuroscience, Henderson, NV)

- Rhythm+ photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors (Scosche Industries)

- VR headset (e.g., Meta Quest 2) with 1832×1920 per eye resolution, 90 Hz refresh rate

- 2D display control (32-inch HD monitors, 1920×1080 resolution positioned 24 inches from participants)

Procedure:

- Apply PPG sensors according to manufacturer specifications for cranial nerve signal detection.

- Establish baseline neural measurements for 3-5 minutes before content exposure.

- Randomly assign participants to VR or 2D conditions using standardized randomization procedures.

- Present identical narrative content in both conditions (5-7 minute runtime recommended).

- Record 1 Hz Immersion data stream throughout exposure.

- Calculate both average Immersion and Peak Immersion for each participant.

- Normalize data as change from baseline to control for individual differences.

Analysis:

- Compare Immersion metrics between groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA).

- Correlate Immersion data with behavioral outcomes (e.g., helping behaviors, memory recall, skill acquisition).

- Conduct mediation analysis to determine whether Immersion explains group differences in outcomes.

Protocol for Cell-Type-Specific Investigation of Molecular Mechanisms

Objective: To isolate the contribution of specific receptor systems in defined neuronal populations to VR-induced plasticity.

Materials:

- Transgenic mouse lines (e.g., NEX-Cre and PV-Cre for pyramidal and parvalbumin neuron targeting)

- Optogenetic tools (chimeric mOpn4L construct targeted to 5-HT2A receptor domains)

- Multi-channel silicon probes for extracellular recordings

- Visual stimulation system (vertical or horizontal gratings with 100% contrast)

- Custom VR environment for mouse navigation

Procedure:

- Express light-activated melanopsin (mOpn4L) in 5-HT2A receptor domains in target cell populations.

- Perform in vivo recordings in primary visual cortex (V1) during visual stimulation.

- Measure neuronal activity during: (a) spontaneous activity (S), (b) spontaneous activity with photostimulation (Sph), (c) visual stimulation alone (V), and (d) visual stimulation with concurrent photostimulation (Vph).

- Classify single units as putative excitatory or inhibitory neurons based on waveform characteristics.

- Calculate opto-index (OI) to quantify modulation effects: OI = (Sph - S) / (Sph + S).

Analysis:

- Compare spontaneous firing rates with and without photostimulation across cell types.

- Analyze visually evoked responses with and without concurrent receptor pathway activation.

- Compute OI probability density functions to characterize population-level effects.

- Model network mechanisms underlying observed gain control effects.

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathways of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity. This diagram illustrates the progression from multi-sensory VR input through activation of specific molecular pathways to resulting neural changes and behavioral outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

| Tool/Reagent | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Immersion Neuroscience Platform | 1 Hz data stream from PPG sensors; measures convolved attention and emotional resonance signals | Quantifying neurologic value of VR experiences; predicting behavioral outcomes [28] |

| Optogenetic 5-HT2A Tools | Chimeric mOpn4L construct targeted to endogenous 5-HT2A receptor domains; activates Gq-signaling pathway | Cell-type-specific manipulation of serotonin receptor signaling in defined neuronal populations [29] |

| High-Density Silicon Probes | Multi-channel extracellular recording arrays with good single-unit isolation | Dense spatial sampling of neural activity across cortical layers during VR exposure [29] |

| Meta Quest 2 VR Headsets | 1832×1920 per eye resolution; 90 Hz refresh rate; 89° horizontal field of view | Presenting immersive VR stimuli with high visual fidelity for human studies [28] |

| Insta360 Pro2 VR Cameras | 8K resolution; 180° VR capture capability | Creating ecologically valid VR content with high immersion potential [28] |

| Rhythm+ PPG Sensors | Photoplethysmography sensors for cranial nerve signal detection | Measuring physiological correlates of engagement and emotional resonance [28] |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for VR Neuroplasticity Research. This diagram outlines the key stages in designing and executing studies on VR-induced synaptic changes, from subject preparation through data analysis.

The investigation of VR-induced learning at the molecular level reveals a complex interplay between sensory input, neuromodulatory systems, and synaptic plasticity mechanisms. The 5-HT2A receptor-mediated gain control, dopamine-driven value signals, and oxytocin-enhanced emotional resonance work in concert to create optimal conditions for experience-dependent neuroplasticity. The integration of BCI technologies with VR further enhances this potential by creating adaptive, closed-loop systems that respond to the user's neural state in real time.

Future research directions should include:

- Multi-scale investigations linking molecular changes to circuit reorganization and behavioral outcomes across longer timeframes.

- Personalized VR protocols based on individual genetic profiles affecting neuromodulatory system function.

- Advanced optogenetic tools for manipulating multiple receptor systems simultaneously during VR exposure.

- Standardized metrics for comparing neuroplastic outcomes across different VR platforms and content types.

As these technologies mature, VR-based interventions promise to revolutionize approaches to neurological rehabilitation, cognitive enhancement, and mental health treatment by leveraging the brain's innate plastic capacities through precisely controlled experiential paradigms.

From Lab to Clinic: Methodologies and Translational Applications in VR Neuroscience

This technical guide outlines best practices for integrating electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) within virtual reality (VR) settings to study brain activity. Combining these multimodal technologies offers unprecedented opportunities to capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of neural processes during immersive experiences. However, this integration presents significant technical and methodological challenges. This document provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, covering technical specifications, safety protocols, experimental design, and data analysis methods to optimize data quality and enable groundbreaking discoveries in neuroscience and drug development.

Understanding the neural basis of brain functioning requires knowledge about both the spatial and temporal aspects of information processing. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) are two techniques widely used to noninvasively investigate human brain function, yet neither alone can provide the complete picture [30]. fMRI yields highly localized measures of brain activation with good spatial resolution (approximately 2–3 mm) but suffers from a limited temporal resolution. In contrast, EEG provides the millisecond-scale temporal resolution necessary to study brain dynamics but lacks precise spatial localization [30]. The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) into this multimodal framework creates powerful, ecologically valid paradigms for studying brain function during immersive behavioral tasks [31] [32].

This guide synthesizes current best practices for leveraging these technologies in concert, focusing on the technical hurdles of simultaneous EEG-fMRI acquisition, their integration with VR presentation systems, and the application of this approach in research on brain activity.

Core Principles and Measurement Technologies

Electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG signals recorded on the scalp surface arise from large dendritic currents generated by the quasi-synchronous firing of large populations of neurons [30]. Scalp EEG is considered an indirect measure of neural activity because the electrical signals are attenuated and distorted as they pass through the brain and skull, a phenomenon known as volume conduction [33]. This makes EEG source localization an ill-posed problem. The primary strength of EEG is its capacity to measure neural activity on a millisecond timescale, capturing the rapidly changing dynamics of neuronal populations [33].

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

fMRI does not measure neural activity directly but rather a correlate known as the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal. Increased neural activity stimulates higher energy consumption, triggering a process called neurovascular coupling that increases local blood flow and blood oxygenation [33]. These hemodynamic changes occur over seconds, which limits the temporal resolution of BOLD fMRI. However, it provides a 3-dimensional map of regional brain activity with sub-millimetre spatial resolution, allowing for excellent spatial localization of brain activity [33].

The Complementary Nature of EEG and fMRI

Given the strengths and deficits of each method, combining them has the potential to provide insight into brain function that cannot be measured by one modality alone [33]. Obtaining complementary datasets in response to the same spontaneous or evoked brain activity is particularly valuable for capturing events like epileptic spikes, resting-state fluctuations, or task responses in cognitive experiments [33] [30]. Furthermore, simultaneous recording eliminates habituation effects, ensures a consistent sensory environment, and reduces overall experimental time [33].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Neuroimaging Modalities

| Feature | EEG | fMRI (BOLD) | Combined EEG-fMRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Poor (centimeters) | High (millimeters) | High (from fMRI) |

| Temporal Resolution | Excellent (milliseconds) | Poor (seconds) | Excellent (from EEG) |

| Measured Signal | Scalp electrical potentials | Blood oxygenation changes | Neural + hemodynamic data |

| Key Strength | Timing of neural dynamics | Localization of brain activity | Spatio-temporal brain mapping |

The Role of Virtual Reality

VR introduces a controlled yet immersive environment that can closely mirror real-life situations. Immersive VR (iVR), often achieved via head-mounted displays (HMDs), creates a sensory-rich virtual experience that simulates the user's physical presence in a digital space [34]. For brain research, iVR facilitates the development of diverse tasks and scenarios that can stimulate the brain within a controlled and secure setting, offering a powerful tool for studying cognitive, behavioral, and motor functions [34] [32]. Studies have shown that VR-based learning can exhibit optimal neural efficiency, suggesting it may foster more efficient learning than real-world environments by providing more intelligible 3D visual cues [35].

Technical Challenges and Integration Solutions

Combining EEG, fMRI, and VR is not without significant challenges, which require careful engineering and procedural solutions to ensure safety and data quality.

Safety in Simultaneous EEG-fMRI

The primary safety concern of placing an EEG system inside an MRI scanner is heating of the EEG components and the participant's local tissue [33]. The MRI's radio frequency (RF) fields and switching gradient fields can induce electromotive forces, generating currents in the conductive loops formed by EEG electrodes and lead wires.

Best Practices for Safety:

- Use MR-Compatible EEG Systems: EEG systems must use non-ferrous materials and components. Electrodes should incorporate current-limiting resistors to reduce the risk of heating, though this does not offer complete protection [33] [36].

- Lead Wire Material: Consider using materials less conductive than copper, such as carbon fibre leads, which have been shown to heat less during MRI scans [33].

- Cable Management: Ensure there are no wire loops in the EEG leads, as these can exacerbate heating. Cabling should be isolated from MR scanner vibrations and follow the shortest path out of the head coil [36].

- RF Coil Selection: Where possible, use a head-sized transmit coil to minimize the risk of RF heating. However, this must be balanced against the need for optimal fMRI data quality, which may require a multi-element receiver coil [36].

Data Quality and Artifact Reduction

EEG data acquired during simultaneous fMRI are contaminated by several large artifacts that can overwhelm the neuronal signals of interest.

Major Artifacts and Mitigation Strategies:

Gradient Artifact: Caused by the rapidly switching magnetic field gradients required for fMRI. It is the largest artifact in the EEG signal [36].

Ballistocardiogram (BCG) Artifact: Also known as the pulse artifact, it is linked to the cardiac cycle and caused by small head movements and Hall effects due to pulsating blood flow in the static magnetic field [30].

Movement Artifacts: Result from head motion in the strong magnetic field and from muscle activity.

- Solution: Minimize head motion by padding the subject's head securely within the head coil. Visually inspect EEG data quality after setup to ensure good signal before scanning [36].

Table 2: Summary of Key Artifacts in Simultaneous EEG-fMRI

| Artifact | Cause | Primary Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Artifact | Switching magnetic field gradients | Clock synchronization, post-processing subtraction |

| Ballistocardiogram (BCG) Artifact | Cardiac-cycle induced head/fluid motion | Vectocardiogram (VCG) recording, advanced filtering (ICA) |

| Subject Motion | Head movement in the bore | Secure head padding, subject instruction |

Integrating VR with Neuroimaging

Presenting VR stimuli during neuroimaging requires specialized hardware that functions within the constraints of the MR environment or other imaging setups.

- fMRI-Compatible VR Systems: These systems use MRI-compatible HMDs or projectors that display visuals on screens placed near the subject's head inside the coil. For example, one study used a custom VR system with an MRI-compatible 5DT data glove to measure hand movements in real-time and actuate the motion of virtual hands viewed by the subject in a first-person perspective [31].

- EEG-Compatible VR Systems: VR HMDs can be mounted above an EEG cap. However, this setup may introduce challenges related to evoked potential signal complexity and susceptibility to electrical interference [34].

- fNIRS as an Alternative: Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is highly compatible with VR HMDs as it is less affected by electrical interference. Its portability and higher motion tolerance make it a promising alternative for studies requiring greater participant mobility [34].

Experimental Design and Protocol

A successful multimodal experiment requires meticulous planning from design to execution.

Pre-Experimental Setup

EEG Preparation:

- Select an appropriately sized EEG cap. Position it correctly so the Cz electrode is halfway between the nasion and inion [36].