Multisensory Integration in the Brain: How Virtual Reality is Revolutionizing Neuroscience Research

This article explores the transformative role of Virtual Reality (VR) in studying multisensory integration—the brain's process of merging information from different senses to form a coherent perception.

Multisensory Integration in the Brain: How Virtual Reality is Revolutionizing Neuroscience Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Virtual Reality (VR) in studying multisensory integration—the brain's process of merging information from different senses to form a coherent perception. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational mechanisms of how VR digitally manipulates human senses to probe cognitive functions. The piece further investigates advanced methodological applications, from bespoke experimental platforms to clinical use in neurorehabilitation and therapy. It also addresses critical technical and ethical challenges while evaluating the validation of VR simulations against real-world benchmarks. By synthesizing evidence from recent empirical studies and reviews, this article provides a comprehensive resource on leveraging VR as a controlled, flexible, and ecologically valid tool for advancing our understanding of brain function and disorder.

The Neuroscience of Sensation: How VR Creates Controlled Multisensory Realities

Defining Multisensory Integration and Its Principles

Multisensory integration is defined as the set of neural processes by which information from different sensory modalities—such as visual, auditory, and tactile inputs—is combined to produce a unified perceptual experience that significantly differs from the responses evoked by the individual component stimuli alone [1]. This complex process enables the brain to create a coherent representation of the environment by synthesizing inputs from multiple senses, resulting in perceptual experiences that are richer and more diverse than the sum of their individual parts [1]. The principal function of multisensory neurons, regardless of their brain location, is to pool and integrate information from different senses, resulting in neural responses that are either amplified or diminished compared to unimodal stimulation [1].

Multisensory integration must be distinguished from other multisensory processes such as crossmodal matching (where individual sensory components retain their independence for comparison) and amodal processing (which involves comparing equivalencies in size, intensity, or number across senses without integrating modality-specific information) [1]. The integrated multisensory signals enhance the physiological salience of environmental events, thereby increasing the probability that an organism will respond appropriately and efficiently to stimuli in its environment [1].

Core Principles of Multisensory Integration

Research in neuroscience has established several fundamental principles that govern how the brain combines information from multiple senses. These principles ensure that multisensory integration enhances perceptual accuracy and behavioral performance rather than creating sensory confusion.

Table 1: Core Principles of Multisensory Integration

| Principle | Neural Mechanism | Behavioral Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Principle | Integration occurs when crossmodal stimuli originate from the same location within overlapping receptive fields [1]. | Enhanced detection and localization of stimuli when spatially aligned; depression when spatially disparate [1]. |

| Temporal Principle | Stimuli from different modalities must occur in close temporal proximity to be integrated [2] [1]. | Temporal coherence between stimuli increases integration efficacy; asynchronous stimuli reduce integration [2]. |

| Inverse Effectiveness | The magnitude of multisensory enhancement is inversely related to the effectiveness of individual component stimuli [1]. | Greatest behavioral benefits occur when unimodal stimuli are weak or ambiguous [1]. |

| Modality-Specific Weighting | Bayesian inference models weight sensory inputs according to their reliability [1]. | More reliable sensory cues exert greater influence on the final perceptual estimate [1]. |

The spatial and temporal principles dictate that crossmodal stimuli presented at the same location and time within their respective receptive fields produce enhanced response magnitude, while spatially or temporally disparate stimuli degrade or do not affect responses [1]. The principle of inverse effectiveness indicates that the most significant multisensory benefits occur when individual sensory signals are weak or ambiguous on their own [1]. From a computational perspective, the brain employs modality-specific weighting, where each sensory input is weighted according to its associated noise and reliability, with the final multisensory estimate achieving greater precision than any single modality [1].

Multisensory Integration in Virtual Reality Research

Virtual reality provides an ideal platform for studying multisensory integration because it enables researchers to create controlled yet ecologically valid environments that mimic the multisensory stimulation characterizing real-life conditions [3]. VR bridges the gap between the rigorous control granted by laboratory experiments and the realism needed for a real-world neuroscientific approach [3]. The key advantage of VR in this domain is its capacity to provide synchronous stimuli across multiple modalities while maintaining precise experimental control over parameters such as stimulus type, duration, distance, and temporal coherence [2].

In VR systems, immersion—the extent to which users feel present in the computer-generated environment rather than their actual physical environment—is crucial for creating authentic multisensory experiences [4]. This is achieved through technological components that engage multiple senses, including head-mounted displays for visual stimulation, headphones for auditory input, and haptic devices for tactile feedback [4]. The inclusion of stereoscopic imagery is widely considered the most important factor that enhances immersion in the VR experience [4]. Precise control of auditory, tactile, and olfactory cues by the VR system significantly increases the user's sense of presence within the virtual environment [4].

The temporal coherence between multimodal stimuli is a key factor in cross-modal integration, as demonstrated by the finding that phenomena like the rubber hand illusion do not occur when visual and tactile stimuli are asynchronous [2]. Modern VR platforms address this requirement by ensuring synchronous delivery of multimodal sensory stimuli while tracking human motion and correspondingly controlling a virtual avatar in real-time [2].

VR Platform Architecture for Multisensory Research

Experimental Protocols for Studying Multisensory Integration

Visuo-Tactile Integration for Peripersonal Space Investigation

A validated experimental protocol for investigating multisensory integration in peripersonal space (PPS) utilizes a virtual reality platform to provide precisely controlled multimodal stimuli [2]. The PPS can be defined as the human body's field of action, where the brain differentiates between space close to the body and far space based on potential for interaction with objects [2]. The protocol employs a reaction time task that combines tactile and visual stimuli to measure how spatial proximity affects multisensory integration.

Methodology: Participants are asked to react as fast as possible to a tactile stimulus provided on their right index finger, regardless of eventual visual stimuli [2]. The protocol begins with a familiarization phase where participants, in first-person perspective, move their arm to control a virtual avatar in a simple reaching task. This goal-oriented task enhances agency and embodiment of the virtual arm while familiarizing participants with the VR environment [2]. The experimental phase consists of multiple sessions with different stimulus conditions:

- V Condition: Visual stimulus only (control)

- T Condition: Tactile stimulus only (control)

- VT Condition: Visual and tactile simultaneous stimuli (experimental)

The visual stimulus is presented as a red light with a semi-sphere shape (similar to an LED) that appears on a virtual table surface for 100 milliseconds [2]. The LED position is randomly selected according to specific spatial criteria, ensuring it appears only in the right hemispace relative to the participant's thorax, at varying distances from the hand, but never directly on the hand or arm [2]. The platform includes infrared cameras that track participant motion through reflective passive markers attached to 3D-printed rigid bodies placed on thorax, arms, forearms, and hands [2].

Naturalistic Target Detection in VR Environments

Another innovative protocol examines multisensory integration using a naturalistic target detection task within an immersive VR environment that simulates real-world conditions [3]. This approach leverages VR's capacity to create realistic scenarios that mimic the multisensory stimulation characterizing natural environments while maintaining experimental control.

Methodology: Participants explore a virtual scenario consisting of a car on a racetrack from a driver's first-person perspective using an Oculus Rift head-mounted display [3]. The experiment manipulates perceptual load—defined as the amount of information involved in processing task stimuli—through environmental conditions. In low-load conditions, visibility is high with sunny weather, while high-load conditions feature mist, rainy weather, and thunder that decrease visibility and increase environmental noise [3].

During the task, participants drive the car while attempting to hit slightly transparent sphere-like objects that spawn randomly on the left or right side of the track [3]. Different multimodal stimuli (auditory and vibrotactile) are presented alone or in combination with the visual targets. Vibrotactile feedback is delivered through DC vibrating motors applied to a wearable belt, while audio feedback is provided through headphones [3]. The experiment concomitantly acquires Electroencephalography (EEG) and Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) to measure neural correlates and arousal levels during task performance [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Findings from Multisensory Integration Studies

| Study Paradigm | Performance Measures | Neural Correlates | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visuo-Tactile PPS [2] | Reaction time to tactile stimuli | Hand-distance correlation (p=0.013) | Significant correlation between hand distance from visual stimulus and reaction time to tactile stimulus [2]. |

| Naturalistic Target Detection [3] | Target detection accuracy | P300 latency and amplitude, EEG workload | Multisensory stimuli improved performance only in high load conditions; trimodal stimulation enhanced presence [3]. |

| VR Cognitive Training [5] | Comprehensive Cognitive Ability Test (67.0% vs 48.2%) | Recall accuracy, spatial positioning | Multisensory VR group outperformed visual-only group in spatial positioning, detailed memory, and time sequencing [5]. |

| Respiratory Modulation [6] | Reaction time variability | Respiratory phase locking | Reaction times varied systematically with respiration, with faster responses during peak inspiration and early expiration [6]. |

Neural Mechanisms and Computational Frameworks

Neural Substrates of Multisensory Integration

The superior colliculus (SC), located on the surface of the midbrain, serves as a primary model system for understanding the neural principles underlying multisensory integration [1]. The SC receives converging visual, auditory, and somatosensory inputs, and its neurons are involved in attentive and orientation behaviors, including the initiation and control of eye and head movements for gaze fixation [1]. Multisensory neurons in the SC exhibit overlapping receptive fields for different modalities, ensuring that inputs from common areas of sensory space are integrated [1].

Beyond the SC, multiple cortical regions contribute to multisensory processing, including the posterior parietal cortex (PPC), which has multisensory integration characteristics that facilitate cross-modal plasticity, enabling intact sensory modalities to compensate for deprived senses [1]. The superior temporal sulcus and premotor cortex also exhibit multisensory integration capabilities, particularly for complex stimuli such as audiovisual speech [1].

At the cellular level, multisensory integration involves nonlinear summation of inputs, with both superadditive and subadditive interactions observed depending on the efficacy of the modality-specific component stimuli [1]. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor involvement and lateral excitatory and inhibitory circuits contribute to supralinear responses, while network-level mechanisms such as recurrent excitation amplify activity across neural populations [1].

Computational Models of Multisensory Integration

Bayesian inference models provide the dominant computational framework for understanding multisensory integration, describing how the brain optimally combines sensory cues based on their reliability and prior expectations [1]. These models implement maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), where each sensory input is weighted according to its associated noise, and the final perceptual estimate is computed as a weighted sum of unimodal sensory signals [1].

Bayesian causal inference models describe how the brain determines whether sensory cues originate from a common source, influencing whether signals are integrated or segregated [1]. This process is essential for avoiding erroneous integration of unrelated sensory events. The reliability of each cue is formally defined as the inverse of its variance, and the combined multisensory estimate achieves greater precision than any single modality, with maximal variance reduction occurring when the variances of individual cues are equal [1].

Probabilistic population codes (PPC) provide a neural framework for implementing Bayesian cue integration, where populations of neurons encode the likelihood of sensory inputs and their reliability [1]. In PPC models, the posterior probability distribution over stimuli is computed by multiplying the likelihoods encoded by different neural populations, with additivity in neural responses predicted as a characteristic outcome of multisensory integration [1].

Multisensory Integration: From Neural Mechanisms to Behavior

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multisensory Integration Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Experimental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware | Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, vibrating tactile belts, motion tracking systems [2] [3] | Creates immersive multisensory environments with precise stimulus control | Peripersonal space mapping, naturalistic target detection, cognitive training [2] [3] [5] |

| Neuroimaging | EEG, fMRI, GSR, eye-tracking [3] | Measures neural correlates, cognitive workload, and physiological responses | P300 analysis, workload assessment, arousal measurement during multisensory tasks [3] |

| Stimulation Devices | Electric stimulators, vibrating motors, audio headphones, olfactory dispensers [2] [5] | Delivers controlled unimodal and crossmodal stimuli | Tactile stimulation, auditory cues, olfactory triggers in multisensory paradigms [2] [5] |

| Computational Tools | Bayesian modeling software, reinforcement learning algorithms, drift diffusion models [7] [1] | Analyzes behavioral data and implements computational frameworks | Reliability weighting, causal inference, decision process modeling [7] [1] |

| Pharmacological Agents | Oxytocin, cholinergic medications [1] | Modulates neural plasticity and crossmodal integration | Enhancing multisensory plasticity, facilitating rehabilitation [1] |

Emerging Research Directions and Clinical Applications

Developmental Trajectories and Plasticity

Multisensory integration capabilities develop gradually during the postnatal period and are highly dependent on experience with cross-modal cues [1]. In normally developing individuals, this capacity reaches maturity before adolescence, but in the absence of specific cross-modal experiences, neurons may not develop typical integration capabilities [1]. Research has identified sensitive periods during which experience is particularly effective in shaping the functional architecture of multisensory brain networks [1].

Notably, individuals born with congenital sensory deficits such as binocular cataracts or deafness show impaired multisensory integration when sensory function is restored after critical developmental windows [1]. For example, congenitally deaf children fitted with cochlear implants within the first 2.5 years of life exhibit the McGurk effect (where visual speech cues influence auditory perception), whereas those receiving implants after this age cannot integrate auditory and visual speech cues [1]. This highlights the importance of early crossmodal experience for the development of typical multisensory integration.

Clinical Applications and Rehabilitation Strategies

Multisensory integration principles are being leveraged for various clinical applications, particularly in rehabilitation and cognitive training. In visual rehabilitation, techniques such as Audio-Visual Scanning Training (AViST) integrate multisensory stimulation to engage the superior colliculus and related neural circuits, improving spatial awareness and oculomotor functions in individuals with visual field defects [8]. These approaches leverage cross-modal plasticity—the brain's ability to reorganize itself when sensory inputs are modified—to enhance processing of remaining sensory inputs [8].

For cognitive enhancement in older adults, multisensory VR reminiscence therapy has demonstrated significant benefits. Recent research shows that older adults using multisensory VR systems incorporating visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory stimuli outperformed visual-only VR users in spatial positioning, detailed memory, and time sequencing tasks [5]. The experimental group achieved an average accuracy rate of 67.0% in comprehensive cognitive testing compared to 48.2% in the visual-only group [5]. These findings highlight the potential of targeted multisensory stimulation to mitigate age-related cognitive decline.

In pain management, VR has emerged as an effective non-pharmacological intervention that leverages multisensory distraction. Research demonstrates that VR can reduce pain perception during medical procedures, with controlled trials showing greater pain reduction in children undergoing burn treatment compared to interacting with a child care worker or listening to music [4]. The immersive quality of VR "hijacks" the user's auditory, visual, and proprioception senses, acting as a distraction that limits the ability to process painful stimuli from the real world [4].

Multisensory integration represents a fundamental neural process through which the brain creates a coherent representation of the environment by combining information across sensory modalities. The core principles of spatial and temporal coincidence, inverse effectiveness, and reliability-based weighting ensure that this integration enhances perceptual accuracy and behavioral performance rather than creating sensory confusion. Virtual reality platforms provide powerful tools for investigating these processes under controlled yet ecologically valid conditions, enabling researchers to precisely manipulate stimulus parameters while measuring behavioral and neural responses. The continuing integration of VR technology with computational modeling, neuroimaging, and interventional approaches promises to advance both our basic understanding of multisensory integration and its applications in clinical rehabilitation and cognitive enhancement.

VR as a Tool for Sensory Digitalization, Substitution, and Augmentation

Virtual Reality (VR) is revolutionizing the study of multisensory integration by providing researchers with unprecedented control over complex, ecologically valid environments. This technical guide examines VR's role in sensory digitalization (the precise capture and rendering of sensory stimuli), sensory substitution (conveying information typically received by one sense through another), and sensory augmentation (enhancing perception beyond normal biological limits). Framed within brain research, VR serves as a powerful experimental platform for investigating the neural mechanisms, such as cross-modal plasticity and optimal integration, that underpin multisensory perception [9] [8]. The immersion and precise stimulus control offered by VR enable the study of these fundamental brain processes in ways that traditional laboratory setups cannot match [10].

Neuroscientific Foundations of Multisensory Integration

Multisensory integration is a critical neural process through which the brain combines information from different sensory modalities to form a coherent percept of the environment. Key brain structures involved include the superior colliculus (SC), pulvinar, and prefrontal cortex (PFC) [9] [8]. The SC, in particular, contains multisensory cells that coordinate visual and auditory inputs to optimize responses to complex environments, a mechanism vital for tasks such as locating sounds in space and understanding speech in noisy settings [9].

The brain employs sophisticated strategies to integrate sensory information, including Bayesian causal inference to determine whether signals should be integrated or segregated, and statistically optimal integration, which weights cues by their reliability to enhance perceptual accuracy [9] [8] [11]. The principle of inverse effectiveness states that multisensory integration is most potent when individual unisensory cues are weak or unreliable [12]. Furthermore, cross-modal plasticity enables the brain to reorganize itself following sensory loss, allowing remaining senses to compensate and facilitate recovery [9] [8] [13].

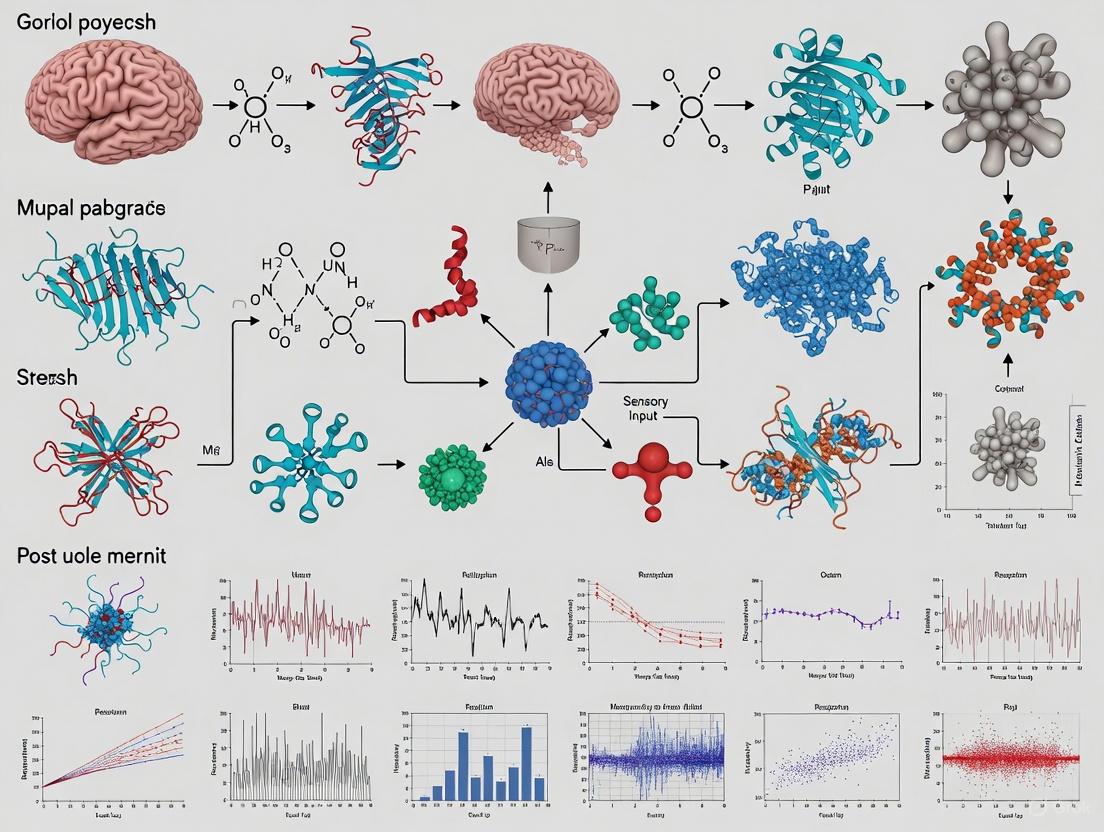

The following diagram illustrates the core neural pathway and principles of multisensory integration, from initial sensory input to unified percept formation.

Neural Pathways and Principles of Multisensory Integration

VR for Sensory Digitalization and Substitution

Sensory Substitution Devices (SSDs) in VR

Sensory Substitution Devices (SSDs) transform information typically acquired through one sensory modality into stimuli for another modality, leveraging the brain's plasticity to interpret this converted information [14] [13]. For the visually impaired, SSDs can convert visual information from a camera into auditory or tactile feedback, enabling users to perceive visual properties like shape, location, and distance through sound or touch [14] [12].

When designing SSDs, several critical principles must be considered to avoid sensory overload and ensure usability. These include focusing on key information rather than attempting to convey all possible data, and respecting the different bandwidth capacities of sensory systems—the visual system has a significantly higher information capacity than the auditory or haptic systems [14]. Furthermore, devices must be designed for spatiotemporal continuity, as perception is a continuous process, not a snapshot of the environment [14].

Experimental Protocol: Audiovisual Detection and Localization

Objective: To quantify the superadditive benefits of multisensory integration for detecting and localizing stimuli using a VR-based paradigm [11].

Setup: The experiment is conducted in a VR environment. Visual stimuli (e.g., brief flashes of light) and auditory stimuli (e.g., short noise bursts) are presented via a head-mounted display (HMD) and integrated spatial audio system. Stimuli can appear at various locations within the virtual space.

Procedure:

- Unisensory Trials: Participants are presented with visual-only (

V) and auditory-only (A) stimuli. - Multisensory Trials: Participants are presented with combined visual-auditory (

VA) stimuli, which can be spatially and temporally congruent or incongruent. - Task: Participants indicate (via button press) when they detect a stimulus and/or identify its perceived location.

- Data Collection: Response accuracy, reaction times, and localization precision are recorded for each condition.

Analysis: Behavioral performance on multisensory trials is compared to the most stringent referent criteria, the sum of the unisensory performance levels (V + A). A superadditive effect—where VA > V + A—demonstrates successful multisensory integration. Data analysis has shown this paradigm produces a consistent proportional enhancement of ~50% in behavioral performance [11].

Table 1: Key Design Principles for Sensory Substitution Devices (SSDs)

| Principle | Description | Application in SSD Design |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Coincidence [12] | Cross-modal information must come from spatially aligned sources for effective integration. | Ensure auditory or tactile feedback is spatially mapped to the location of the visual source in the environment. |

| Temporal Coincidence [12] | Cross-modal information must occur in close temporal proximity. | Minimize latency between a visual event and its corresponding auditory/tactile feedback. |

| Inverse Effectiveness [12] | Multisensory enhancement is greatest when unisensory cues are weak or unreliable. | Design SSDs to provide the greatest benefit in low-information or ambiguous sensory environments. |

| Focus on Key Information [14] | Convey only the most critical information for the task to avoid sensory overload. | For mobility, focus on conveying obstacle location and size, not color or fine texture. |

| Bandwidth Consideration [14] | Acknowledge the different information capacities of sensory channels. | Avoid overloading the auditory channel with visual information that exceeds its processing capacity. |

VR for Sensory Augmentation and Neural Plasticity

Augmenting Sensory Feedback

VR enables sensory augmentation by providing supplementary cross-modal cues that enhance perception and guide behavior. For instance, to combat distance compression (a common issue in VR where users underestimate distances), incongruent auditory-visual stimuli can be artificially aligned to create a more accurate perception of depth [12]. Furthermore, adding temperature cues via wearable devices (e.g., a wristband that provides thermal feedback) during a VR experience can enhance the sense of presence and immersiveness, a technique known as sensory augmentation [15].

Measuring the Impact of VR on the Brain and Behavior

Objective neurophysiological measures are increasingly used to quantify VR's impact. One such measure is neurologic Immersion, a convolved metric that captures the value the brain assigns to an experience by combining signals related to attention and emotional resonance [16]. Studies show that VR generates significantly higher neurologic Immersion (up to 60% more) compared to 2D video presentations. This heightened immersion is positively correlated with outcomes such as improved information recall, increased empathic concern, and a greater likelihood of prosocial behaviors [16].

Experimental Protocol: Cross-Modal Plasticity Training with AViST

Objective: To leverage VR-based Audio-Visual Scanning Training (AViST) to promote cross-modal plasticity and improve visual detection in patients with homonymous visual field defects [9] [8].

Setup: Patients use a VR headset in a controlled setting. The environment is designed to systematically present spatially and temporally congruent auditory and visual stimuli.

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Map the patient's visual field defect (scotoma).

- Training Regimen: Patients undergo repeated sessions where they are tasked with detecting and localizing auditory-visual stimuli presented within and near the borders of their blind field.

- Stimulus Parameters: Stimuli are designed to engage multisensory cells in the superior colliculus by ensuring spatial and temporal coincidence.

- Progression: Task difficulty is progressively increased by reducing stimulus intensity or increasing environmental complexity.

Analysis: Functional improvements are measured through pre- and post-training assessments of visual detection accuracy in the blind field, oculomotor scanning efficiency, and self-reported quality of life measures. The protocol leverages the brain's capacity for neuroplasticity, using auditory cues to facilitate the recovery of visual function [9] [8].

The following workflow diagrams the process of using VR for sensory substitution and augmentation, from stimulus transformation to measuring neuroplastic outcomes.

VR Sensory Substitution and Augmentation Workflow

Quantitative Data on Multisensory Integration Effects

Robust quantitative data is essential for validating the effectiveness of VR in multisensory research. The following tables summarize key behavioral and neurophysiological findings from recent studies.

Table 2: Behavioral Performance in Multisensory vs. Unisensory Conditions (from [11])

| Condition | Detection Accuracy (%) | Localization Precision (% Improvement) | Key Statistical Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Only (V) | Baseline V | - | - |

| Auditory Only (A) | Baseline A | - | - |

| Visual-Auditory (VA) | V + A + ~50% | ~50% improvement over best unisensory condition | VA > V + A (superadditivity), p < 0.001 |

| Optimal Integration Model | Matches observed VA performance | Matches observed VA performance | No significant deviation from model predictions |

Table 3: Neurophysiological and Behavioral Impact of VR vs. 2D Video (from [15] [16])

| Metric | VR Condition | 2D Video Condition | Significance and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurologic Immersion [16] | 60% higher than 2D | Baseline | Peak Immersion is a strong predictor of subsequent prosocial behavior. |

| Empathic Concern [16] | Significantly increased | Lesser increase | Mediates the relationship between Immersion and helping behavior. |

| Content Preference [15] | Nature scenes rated as more restorative | City scenes rated as less restorative | 10-minute durations preferred over 4-minute. |

| Sensory Augmentation [15] | Temperature cues enhanced realism | N/A | Personalized temperature profiles recommended. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential tools and methodologies for building VR-based multisensory research paradigms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for VR Multisensory Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution VR HMD | Presents controlled visual and auditory stimuli. | Meta Quest 2/3, HTC Vive Focus 3. Key specs: resolution (>1832x1920 per eye), refresh rate (90Hz+), field of view. |

| Spatial Audio System | Renders sounds with precise location in 3D space. | Critical for studying spatial coincidence. Software SDKs like Steam Audio or Oculus Spatializer. |

| Tactile/Temperature Transducer | Provides haptic or thermal feedback for substitution/augmentation. | Embr Wave 2 wristband for temperature cues [15]; vibrotactile actuators for touch. |

| Neurophysiology Platform | Objectively measures brain's response to experiences. | Platforms like Immersion Neuroscience which use PPG sensors to derive metrics like neurologic Immersion [16]. |

| SSD Software Library | Algorithms for converting sensory information between modalities. | Converts camera feed to soundscapes (e.g., vOICe) or tactile patterns. Customizable parameters are essential. |

| Optogenetics Setup | Causally investigates neural circuits in animal models. | Not for human VR, but used in foundational studies. Combines light-sensitive proteins, optical fibers, and VR for rodents [9] [8]. |

| Eye-Tracking Module | Measures gaze and oculomotor behavior. | Integrated into modern HMDs. Critical for rehabilitation protocols like VST and AViST [9]. |

VR has emerged as an indispensable platform for studying multisensory integration, enabling rigorous experimentation with sensory digitalization, substitution, and augmentation. Its unique capacity to create immersive, controllable environments allows researchers to probe the neural principles of cross-modal plasticity, inverse effectiveness, and optimal integration with high ecological validity. The quantitative data generated through VR-based paradigms, from behavioral superadditivity to neurophysiological immersion, provides robust evidence for the brain's remarkable ability to adaptively combine sensory information. As VR technology and our understanding of brain plasticity continue to advance, the potential for developing transformative clinical interventions and augmenting human perception will expand correspondingly, solidifying VR's role at the forefront of cognitive and affective neuroscience.

In the field of cognitive neuroscience, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool for studying the brain's intricate processes. This whitepaper examines three core cognitive functions—information processing, memory, and knowledge creation—within the context of VR-based multisensory integration research. Multisensory integration refers to the brain's ability to combine information from different sensory modalities into a coherent perceptual experience, a process crucial for navigating and interpreting complex environments [9]. VR uniquely bridges the gap between highly controlled laboratory experiments and the ecological validity of real-world settings, creating immersive, multimodal environments that enable researchers to investigate these cognitive functions with unprecedented precision and realism [3]. The study of these cognitive domains is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical and clinical researchers developing interventions for neurological disorders, age-related cognitive decline, and sensory processing deficits.

Information Processing in Multisensory Environments

Information processing encompasses the cognitive operations through which sensory input is transformed into meaningful perception. In multisensory VR research, this involves understanding how the brain combines, filters, and prioritizes information from visual, auditory, and tactile channels.

Neural Mechanisms of Multisensory Integration

The brain employs sophisticated strategies for integrating multisensory information. Key structures include the superior colliculus (SC), pulvinar, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), which coordinate to create a unified perceptual experience [9]. Neurons in these regions exhibit multisensory enhancement, where combined sensory inputs produce neural responses greater than the sum of individual unisensory responses [3]. The process involves:

- Bayesian Causal Inference: The brain determines whether sensory signals originate from the same source and should be integrated, or from different sources and should be segregated [9].

- Temporal and Spatial Binding: Inputs from different modalities that occur close in time and space are preferentially integrated, enhancing perceptual accuracy [9].

- Cross-Modal Plasticity: Short-term sensory deprivation (e.g., monocular deprivation) can enhance responsiveness in remaining sensory modalities, demonstrating the adaptive nature of sensory processing networks [9].

The Impact of Perceptual Load

Perceptual load—the amount of information involved in processing task stimuli—significantly modulates multisensory integration efficacy [3]. Research demonstrates that multisensory stimuli produce the most substantial performance benefits under conditions of high perceptual load, where cognitive resources are stretched thin.

Table 1: Performance Improvements with Multisensory Stimulation Under High Perceptual Load

| Performance Metric | Unimodal (Visual) Stimulation | Trimodal (VAT) Stimulation | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Detection Accuracy | Baseline | Significant increase [3] | Not quantified |

| Response Latency | Baseline | Significant decrease [3] | Not quantified |

| P300 Amplitude (EEG) | Baseline | Significant increase [3] | Faster, more effective stimulus processing |

| EEG-based Workload | Baseline | Significant decrease [3] | Reduced cognitive workload |

| Perceived Workload (NASA-TLX) | Baseline | Significant decrease [3] | Lower subjective task demand |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Information Processing

Protocol: Target Detection Task in High/Load Perceptual Conditions [3]

- Objective: To measure how multisensory cues improve target detection under varying perceptual demands.

- Setup: Participants operate a virtual car in a VR racetrack environment (Oculus Rift HMD) with a steering wheel and tactile feedback belt.

- Low Load Condition: High visibility, sunny weather.

- High Load Condition: Low visibility, rainy/misty weather with environmental noise.

- Task: Detect and "hit" transparent sphere-like objects appearing randomly on the track.

- Stimulus Conditions:

- Unimodal: Visual target only.

- Bimodal: Visual target + auditory or tactile cue.

- Trimodal: Visual target + auditory + tactile (VAT) cue.

- Measures: Accuracy, reaction time, EEG (P300 event-related potentials), Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), and NASA Task Load Index.

Memory Systems and Multisensory Encoding

Memory is not a unitary system but comprises multiple subsystems that work in concert to acquire, store, and retrieve information. Multisensory VR environments provide a rich context for investigating how sensory-rich experiences influence these different memory systems.

Mapping Memory Systems to Neural Substrates

Table 2: Memory Systems, Functions, and Neural Correlates

| Memory System | Function | Neural Substrates | VR Research Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Memory [17] | Temporarily stores and manipulates information for cognitive tasks. | Prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, posterior parietal cortex [18]. | Critical for navigating complex VR environments and integrating transient multisensory cues. |

| Episodic Memory [17] | Stores autobiographical events and experiences within their spatial-temporal context. | Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, ventral/anterior left prefrontal cortex [18]. | Enhanced by immersive, narrative-driven VR scenarios that create strong contextual memories. |

| Semantic Memory [17] | Retains general world knowledge and facts. | Likely involves broad cortical networks [17]. | Facilitated by VR simulations that embed factual learning within realistic practice. |

| Procedural Memory [17] | Underpins the learning of motor skills and habits. | Basal ganglia, cerebellum, motor cortex. | VR is ideal for motor skill training (e.g., rehabilitation), where tactile and visual feedback reinforces learning. |

Multisensory Influences on Memory Formation

The integration of congruent auditory and visual stimuli has been shown to facilitate a more cohesive and robust memory trace [9]. This is exemplified by the McGurk effect, where conflicting auditory and visual speech information is integrated to form a novel perceptual memory, demonstrating that memory encoding is not a passive recording but an active, integrative process [9]. Furthermore, VR-based physical activity has been demonstrated to induce both acute and chronic improvements in cognitive and perceptual processes, which are likely supported by underlying memory systems [19].

Knowledge Creation and Cognitive Synthesis

Knowledge creation represents the highest-order cognitive function, involving the synthesis of new insights, concepts, and problem-solving strategies from available information. In VR research, this relates to how users build cognitive maps, infer rules, and develop skills within simulated environments.

Reasoning and Problem-Solving in Virtual Environments

Reasoning is a complex cognitive function that includes sub-processes like spatial processing, planning, and problem-solving [18]. These executive functions primarily recruit the frontoparietal network, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and intraparietal sulcus [18]. VR environments are exceptionally well-suited to study these processes because they:

- Present ill-structured problems that require creative, divergent thinking [17].

- Allow for the safe practice of complex, real-world tasks, facilitating the transition from explicit knowledge to implicit, procedural knowledge [17].

- Enable the study of neural correlates of insight and "aha!" moments during problem-solving within realistic scenarios.

The Role of Presence in Cognitive Synthesis

The sense of "presence"—the subjective feeling of being in the virtual environment—is a critical factor in VR research [3]. Studies show that trimodal (Visual-Audio-Tactile) stimulation is more effective at enhancing presence than bimodal or unimodal stimulation [3]. A strong sense of presence is believed to engage cognitive and neural processes similar to those used in the real world, thereby increasing the ecological validity of the knowledge and skills acquired in the VR environment.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

The investigation of cognitive functions within multisensory VR environments requires standardized, rigorous experimental workflows. The following diagram outlines a typical protocol for a VR-based multisensory study.

Workflow for a VR Multisensory Cognitive Study

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing studies on multisensory integration and cognition in VR, the following tools and assessments are indispensable.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Multisensory VR Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware | Oculus Rift DK2, Oculus Quest 2 [19] [3] | Provides immersive visual display and head-tracking for creating controlled, realistic environments. |

| Tactile Feedback Systems | DC vibrating motors on a wearable belt [3] | Delivers precisely timed vibrotactile stimuli to study touch integration and enhance presence. |

| Neurophysiological Recorders | EEG systems (e.g., 38-channel Galileo BEPlus), GSR (e.g., NeXus-10) [3] | Objectively measures brain activity (P300 ERP, workload bands) and arousal (skin conductance). |

| Cognitive & Behavioral Assessments | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [19], NASA-TLX [3] | Screens general cognitive status and quantifies subjective perceived workload after tasks. |

| Experimental Software | Unity3D [3], Custom VR Games (e.g., 'Seas the Day') [19] | Platform for designing and running multisensory experiments with precise stimulus control. |

| Sensory Stimulation Equipment | High-fidelity headphones [3], Visual displays, Tactile actuators | Presents controlled, high-quality auditory, visual, and tactile stimuli to participants. |

The integration of VR technology with multisensory paradigms provides a powerful and ecologically valid framework for deconstructing the core cognitive functions of information processing, memory, and knowledge creation. The findings demonstrate that multisensory stimulation, particularly under high perceptual load, significantly enhances behavioral performance, reduces neural workload, and strengthens the sense of presence. For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights are critical for designing more effective cognitive assessments and developing targeted interventions that leverage the brain's innate neuroplasticity and multisensory capabilities to improve cognitive function and patient outcomes. Future research should focus on refining these interventions and further elucidating the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underpin these cognitive phenomena.

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) in neuroscience research, particularly for studying multisensory integration, represents a paradigm shift in experimental methodology. At the core of this transformation lies the concept of embodied simulation—the brain's inherent mechanism for understanding actions, emotions, and sensory experiences through the reactivation of neural systems that govern our physical interactions with the world. VR technology uniquely aligns with this mechanism by providing an artificial, controllable environment where users can experience a compelling Sense of Embodiment (SoE) toward a virtual avatar. This sense, defined as the feeling that the virtual body is one's own, combines three subcomponents: Sense of Body Ownership, Sense of Agency, and Sense of Self-Location [20]. By leveraging this alignment, researchers can create precise, reproducible experimental conditions for studying fundamental brain processes, offering unprecedented opportunities for understanding neural mechanisms of multisensory integration and developing novel therapeutic interventions for neurological disorders [21].

The theoretical foundation of embodied simulation suggests that cognition is not an abstract, disembodied process but is fundamentally grounded in the brain's sensorimotor systems. VR interfaces directly engage these systems by providing congruent visuomotor, visuotactile, and proprioceptive feedback, thereby strengthening the illusion of embodiment and facilitating more naturalistic study of brain function [21]. This technical guide explores the mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of VR as a tool for aligning with the brain's operating principles, with particular emphasis on its role in multisensory integration research relevant to drug development and clinical neuroscience.

Theoretical Foundations: The Neuroscience of Embodiment

Neural Correlates of the Sense of Embodiment

The Sense of Embodiment (SoE) emerges from the integrated activity of distributed neural networks that process and unify multisensory information. Key brain regions implicated in SoE include the premotor cortex, posterior parietal cortex, insula, and temporoparietal junction [21]. Neurophysiological studies using electroencephalography (EEG) have identified event-related desynchronization (ERD) in the alpha (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) frequency bands over sensorimotor areas as a reliable correlate of embodied experiences [21]. This ERD pattern reflects the cortical activation associated with motor planning and execution, even during imagined movements, making it a valuable biomarker for studying embodiment in VR environments.

The rubber hand illusion (RHI) and its virtual counterpart, the virtual hand illusion (VHI), provide compelling evidence for the neural plasticity of body representation. These paradigms demonstrate that synchronous visual and tactile stimulation can trick the brain into incorporating artificial limbs into its body schema [21]. Evans and Blanke (2013) demonstrated that VHI and hand motor imagery tasks share similar electrophysiological correlates, specifically ERD in frontoparietal brain areas, suggesting that embodied simulation can enhance neural patterns during cognitive tasks [21]. This neural flexibility forms the basis for using VR to manipulate and study body representation in controlled experimental settings.

Multisensory Integration as the Gateway to Embodiment

Multisensory integration represents the fundamental neural process through which the brain combines information from different sensory modalities to form a coherent perception of the body and environment. The temporal and spatial congruence of cross-modal stimuli is critical for successful integration and the induction of embodiment illusions [21]. When visual, tactile, and proprioceptive signals align consistently, the brain preferentially integrates them according to the maximum likelihood estimation principle, resulting in the perceptual binding of the virtual body to the self.

VR capitalizes on these innate neural mechanisms by providing precisely controlled, congruent multisensory feedback that aligns with the brain's expectations based on prior embodied experiences. This controlled alignment enables researchers to systematically investigate the causal relationships between specific sensory inputs and the resulting neural and perceptual phenomena, offering insights into both typical and atypical multisensory processing across different clinical populations.

Current Research Landscape and Quantitative Findings

Key Studies on VR-Induced Embodiment and Neural Responses

Recent research has established robust connections between VR-induced embodiment and measurable neural activity, particularly through EEG measurements. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from seminal studies in this domain:

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on VR Embodiment and Neural Correlates

| Study | Experimental Paradigm | Participants | Key Neural Metrics | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vagaja et al. (2025) [21] | Within-subject design comparing embodiment priming vs. control | 39 | ERD in alpha/beta bands; Lateralization indices | No significant ERD differences between conditions; Greater variability in lateralization indices during embodied condition |

| Vourvopoulos et al. (2022) [21] | Vibrotactile feedback + embodied VR vs. 2D screen-based MI | Not specified | Alpha ERD lateralization | Stronger and more lateralized Alpha ERD with embodied VR compared to conventional training |

| Du et al. (2021) [21] | Visuotactile stimulation of virtual hand vs. rubber hand preceding MI | Not specified | ERD patterns | Greater ERD following virtual hand stimulation compared to rubber hand |

| Braun et al. (2016) [21] | Correlation analysis between SoE and EEG | Not specified | ERD in sensorimotor areas | Positive correlations between embodiment strength and ERD patterns |

| Škola et al. (2019) [21] | Quantified embodiment and EEG correlation | Not specified | ERD in sensorimotor areas | Positive correlations for Sense of Ownership but negative correlations for Sense of Agency |

Critical Gaps and Inconsistencies in Current Research

Despite promising findings, the field suffers from significant methodological challenges. A recent scoping review highlighted high heterogeneity in VR-induced stimulations and in EEG data collection, preprocessing, and analysis across embodiment studies [20]. Furthermore, subjective feedback is typically collected via non-standardized and often non-validated questionnaires, complicating cross-study comparisons [20]. The relationship between subjective embodiment reports and neural measures remains inconsistently characterized, with studies reporting positive, negative, or non-significant correlations between different embodiment components and EEG metrics [21].

These inconsistencies underscore the need for greater standardization in experimental design and measurement approaches. The lack of reliable EEG-based biomarkers for embodiment continues to pose challenges for reproducible research in this domain [20].

Experimental Protocols for Multisensory Integration Research

Protocol: VR Priming in Motor Imagery Brain-Computer Interfaces

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 confirmatory study, examines the effect of embodiment induction prior to motor imagery (MI) training on subsequent neural responses and BCI performance [21].

Experimental Design and Setup

The study employs a within-subject design where all participants complete both experimental (embodied) and control conditions in counterbalanced order. The experimental setup includes:

- VR System: Head-mounted display (HMD) with hand-tracking capabilities

- EEG System: High-density electroencephalography (at least 32 channels) with sampling rate ≥500Hz

- Virtual Environment: Custom software rendering a first-person perspective of a virtual body

- Data Integration: Synchronization system for EEG and VR stimuli

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for VR-MI Experiment

| Item | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | 32+ channels, sampling rate ≥500Hz, electrode impedance <10kΩ | Records neural activity during embodiment induction and MI tasks |

| VR Head-Mounted Display | Minimum 90Hz refresh rate, 100°+ field of view, 6 degrees of freedom tracking | Presents immersive virtual environment and virtual body |

| Motion Tracking System | Sub-centimeter precision, full-body tracking preferred | Tracks real movements for visuomotor congruence during embodiment induction |

| Tactile Stimulation Device | Vibration motors or similar with precise timing control (<10ms latency) | Provides congruent visuotactile stimulation during embodiment induction |

| Data Synchronization Unit | Hardware/software solution for millisecond-precise timing | Synchronizes EEG, VR events, and tactile stimulation for precise temporal alignment |

| Experimental Control Software | Custom or commercial (e.g., Unity3D, Unreal Engine) | Prescribes experimental paradigm and records behavioral responses |

Procedure and Timeline

The experiment consists of three primary phases conducted in a single session:

Baseline EEG Recording (5 minutes)

- Resting-state EEG with eyes open and closed

- Actual movement execution for sensorimotor rhythm calibration

Experimental Manipulation (15 minutes)

- Embodied Condition: Participants undergo embodiment induction through synchronous visuomotor and visuotactile stimulation while observing the virtual body from first-person perspective

- Control Condition: Participants receive asynchronous stimulation or observe the virtual body from third-person perspective

MI-BCI Training (30 minutes)

- Participants perform cued motor imagery (e.g., left vs. right hand grasping)

- Real-time neurofeedback provided through VR display

- EEG recorded continuously throughout training

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for VR Priming Study

Data Analysis Methods

EEG Preprocessing:

- Bandpass filtering (0.5-40 Hz)

- Artifact removal (ocular, muscular, movement)

- Independent component analysis for artifact identification

- Epoch extraction time-locked to MI cues

Primary Outcome Measures:

- ERD Calculation: Percentage power decrease in alpha (8-13Hz) and beta (13-30Hz) bands during MI compared to baseline

- Lateralization Index: (Contralateral ERD - Ipsilateral ERD) / (Contralateral ERD + Ipsilateral ERD) for hemisphere-specific effects

- Subjective Measures: Standardized embodiment questionnaires (e.g., custom scales based on Kilteni et al., 2012) administered after each condition [21]

Protocol: Evaluating Sense of Embodiment with EEG

This protocol, derived from a scoping review of 41 studies, provides a framework for standardized assessment of embodiment components using EEG [20].

Experimental Modulations of Embodiment Components

The protocol systematically modulates each component of embodiment through specific experimental manipulations:

Sense of Body Ownership:

- Visual appearance matching (virtual body resembles participant's actual body)

- Synchronous vs. asynchronous visuotactile stimulation

- Body transfer illusions

Sense of Agency:

- Temporal congruence between intended actions and virtual body movements

- Degree of control over virtual body movements

- Spatial congruence between motor commands and visual feedback

Sense of Self-Location:

- First-person versus third-person perspective

- Visuoproprioceptive congruence

- Collision detection between virtual body and environment

Figure 2: Multisensory Integration Pathways to Embodiment

EEG Metrics for Embodiment Assessment

The following quantitative EEG metrics should be derived for comprehensive embodiment assessment:

Table 3: EEG Biomarkers for Embodiment Components

| Embodiment Component | EEG Metric | Neural Correlates | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Ownership | ERD/S in sensorimotor alpha/beta bands | Premotor cortex, posterior parietal | Increased ERD indicates stronger embodiment |

| Sense of Agency | Movement-related cortical potentials (MRCP) | Supplementary motor area, prefrontal cortex | Earlier onset with higher agency |

| Agency | Frontal-midline theta power (4-7Hz) | Anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal | Increased theta with agency violation |

| Self-Location | Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) | Occipital and parietal regions | Modulation by perspective changes |

| Global Embodiment | Cross-frequency coupling | Large-scale network integration | Theta-gamma coupling as integration marker |

Technical Implementation and Methodological Considerations

VR System Configuration for Multisensory Research

Optimal VR system configuration for multisensory integration research requires careful attention to technical specifications that directly impact embodiment induction:

Visual System Requirements:

- Refresh Rate: Minimum 90Hz to prevent motion sickness and maintain presence

- Display Resolution: Minimum 20 pixels per degree visual angle for realistic body representation

- Tracking Latency: <20ms motion-to-photon latency for visuomotor congruence

- Field of View: ≥100° for peripheral visual integration

Haptic/Tactile System Requirements:

- Temporal Precision: <10ms synchronization between visual and tactile events

- Spatial Precision: Sub-centimeter accuracy for aligned visuotactile stimulation

- Actuator Type: Vibration motors, pneumatic devices, or electrical stimulation based on research question

Auditory System Requirements:

- Spatial Audio: Head-related transfer function implementation for veridical sound localization

- Latency: <15ms for audio-visual synchronization

EEG-VR Integration Challenges and Solutions

Integrating EEG with VR systems presents unique technical challenges that must be addressed for valid data collection:

Artifact Mitigation:

- Motion Artifacts: Use of specialized EEG caps with secure electrode placement, motion-tolerant amplifiers

- EMG Artifacts: Strategic electrode placement away from neck and jaw muscles

- BCG Artifacts: Algorithmic correction for ballistocardiogram artifacts

Synchronization:

- Hardware-based synchronization using TTL pulses or specialized synchronization units

- Software-level timestamp alignment with network time protocol

- Validation of synchronization precision using external photodiode testing

Signal Quality Maintenance:

- Regular impedance checks throughout the experiment

- Use of active electrodes in high-movement environments

- Electrode fixation with additional stabilizing systems

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Clinical Neuroscience

The alignment of VR with the brain's inherent operating mechanisms through embodied simulation offers significant potential for pharmaceutical research and clinical applications.

Quantitative Assessment of Neurological Function

VR-based embodied paradigms provide sensitive, quantitative measures for assessing neurological function and treatment efficacy:

Stroke Rehabilitation:

- VR-based MI-BCI systems promote neuroplasticity by stimulating lesioned sensorimotor areas [21]

- Stronger ERD during embodied MI training correlates with better motor recovery outcomes [21]

- Real-time embodied feedback enhances engagement and facilitates brain activity modulation [21]

Neurodegenerative Disorders:

- Assessment of body ownership disturbances in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease

- Quantitative measures of agency for early detection of cognitive decline

- Rehabilitation of spatial navigation deficits through embodied VR training

Psychiatric Conditions:

- Modulation of body representation in body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders

- Agency assessment in schizophrenia spectrum disorders

- Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders using graded embodiment manipulations

Drug Development Applications

VR embodiment metrics offer novel endpoints for clinical trials in neurological and psychiatric drug development:

Biomarker Development:

- EEG-derived embodiment measures as quantitative biomarkers for treatment response

- Objective assessment of drug effects on multisensory integration processes

- Dose-response characterization using sensitive neural measures of embodiment

Proof-of-Concept Studies:

- Early efficacy signals through changes in embodiment-related ERD patterns

- Target engagement verification through modulation of specific embodiment components

- Comparative effectiveness research using standardized VR embodiment paradigms

Future Directions and Standardization Needs

As VR continues to evolve as a tool for studying multisensory integration, several critical areas require attention to advance the field:

Methodological Standardization

The high heterogeneity in current VR embodiment research necessitates concerted standardization efforts:

Experimental Protocols:

- Development of minimal reporting standards for VR embodiment studies

- Standardized embodiment induction protocols with specified parameters

- Consensus on objective and subjective measures for each embodiment component

EEG Methodology:

- Standardized preprocessing pipelines for VR-EEG data

- Best practices for artifact handling in movement-rich VR environments

- Reference datasets for validation and benchmarking

Technological Advancements

Emerging technologies offer promising directions for enhancing VR's alignment with neural mechanisms:

Advanced Haptics:

- High-fidelity tactile feedback systems for realistic touch simulation

- Thermal feedback integration for more comprehensive multisensory experiences

- Force feedback devices for proprioceptive enhancement

Brain-Computer Interface Integration:

- Closed-loop systems that adapt VR content in real-time based on neural activity

- Hybrid BCI approaches combining EEG with fNIRS or other modalities

- Adaptive embodiment manipulation based on ongoing brain states

Mobile and Accessible VR:

- Lightweight, wireless VR systems for more natural movement

- Cloud-based processing for complex multisensory integration scenarios

- Integration with everyday devices for ecological assessment

Through continued methodological refinement and technological innovation, VR-based embodied simulation promises to become an increasingly powerful tool for elucidating the brain's multisensory integration mechanisms and developing novel interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The study of multisensory integration in the brain represents a frontier where virtual reality (VR) serves as a critical experimental platform. This research sits at the convergence of three disciplines: Information Systems (IS), which provides the architectural framework for digitalization, substitution, augmentation, and modification of human senses; Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), which designs the user-centered interfaces and experiences; and Cognitive Psychology, which investigates the underlying mental processes of perception, memory, and information processing [22]. Virtual technologies have revolutionized these fields by enabling the precise control and manipulation of sensory inputs necessary for studying brain function [22]. Despite growing attention, the specific mechanisms through which sensory perception in multimodal virtual environments impacts cognitive functions remain incompletely understood [22] [5]. This whitepaper synthesizes current experimental findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks to guide researchers and drug development professionals in leveraging VR for multisensory brain research.

Core Cognitive Domains and Multisensory Influences

VR-based cognitive training systems target specific cognitive domains through structured tasks. Research identifies several key domains particularly responsive to multisensory VR interventions, with measurable impacts on cognitive functions essential for daily living [23].

Table 1: Key Cognitive Domains and Their Multisensory Correlates

| Cognitive Domain | Impact of Multisensory VR | Relevant Neuropsychological Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Memory | Improved detailed memory recall and autobiographical retrieval through combined visual, auditory, and olfactory cues [5] [24]. | Visual Patterns Test, n-back Task, Paired-Associate Learning [23]. |

| Attention | Enhanced sustained and selective attention through engaging, embodied tasks requiring motor responses [23]. | Dual-task Paradigms, Psychomotor Vigilance Test [23]. |

| Information Processing | Increased speed and accuracy of processing through adaptive difficulty and naturalistic interaction [23]. | Trail Making Test, Paced Visual Serial Addition Task [23]. |

| Spatial Positioning | Superior spatial awareness and navigation via congruent visual-proprioceptive-olfactory integration [5]. | Custom wayfinding and spatial navigation tasks [5]. |

| Executive Function | Enhanced problem-solving and task flexibility through immersive scenarios requiring real-time decision-making [23]. | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Stroop Task, Towers of Hanoi [23]. |

Quantitative Findings: Efficacy of Multisensory VR Interventions

Recent empirical studies provide quantitative evidence supporting the cognitive enhancement effects of multisensory VR compared to visual-only stimulation. The data below summarizes key performance metrics from controlled experiments.

Table 2: Cognitive Performance Outcomes in Multisensory VR Studies

| Study & Intervention | Participant Group | Key Performance Metrics | Result Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multisensory VR Reminiscence [5] | Older Adults (65-75 yrs); n=15 per group | Comprehensive Cognitive Ability Test (Accuracy) | Multisensory Group: 67.0%Visual-Only Group: 48.2%(p < 0.001) |

| Portal Scene Recognition [24] | Mixed adults; sensory conditions varied | Scene Recognition Accuracy & Response Time | Significant improvement in both accuracy and response time with visual+auditory+olfactory cues vs. visual-only. |

| Enhance VR Cognitive Training [23] | Healthy & MCI older adults | Transfer to Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) | VR provides higher ecological validity and better transfer to ADLs vs. screen-based systems. |

| VR, Creativity & Recall [25] | Student participants; n per group varied | Recall and Creativity Scores | Highest recall with traditional 2D video; Enhanced creativity with VR and VR+Scent conditions. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Multisensory VR Reminiscence Therapy for Older Adults

This protocol evaluates the impact of multisensory VR on spatial positioning, detailed memory, and time sequencing in older adults [5].

- Participant Recruitment and Allocation: Recruit 30 older adults (ages 65-75) with no prior VR experience. Assess baseline cognition using the Hasegawa's Dementia Scale-Revised (HDS-R). Use stratified random allocation to assign 15 participants to an experimental group (multisensory VR) and 15 to a control group (visual-only VR), balancing for age, gender, and HDS-R scores [5].

- VR Stimulus Design and Cultural Relevance: Develop a VR environment simulating a familiar cultural context (e.g., a traditional Taiwanese agricultural village). For the experimental group, integrate four sensory modalities:

- Visual: Authentic scenes of farm life, tools, and activities.

- Auditory: Ambient sounds (e.g., farm animals, wind, flowing water).

- Olfactory: Relevant scents (e.g., soil, hay, flowers) delivered via an olfactory device.

- Tactile: Haptic feedback through controllers when interacting with objects [5].

- Procedure and Training Phases: Conduct the intervention across four distinct stages of reminiscence-based cognitive training. In each session, participants freely explore the VR environment and are prompted by a guide to recall specific personal memories related to the scenes. Each session lasts approximately 90-100 minutes [5].

- Outcome Measures: Administer post-intervention assessments:

- Comprehensive Cognitive Ability Test Questionnaire: Measures overall cognitive performance.

- Cognitive Function Recall Effectiveness Scale: Assesses memory recall capabilities.

- Multisensory Stimulation and Cognitive Rule Correspondence Assessment Scale: Evaluates how well sensory cues corresponded to cognitive tasks [5].

Protocol: Evaluating Sensory Cues in VR Portal Recognition

This protocol investigates how auditory and olfactory cues compensate for limited visual information in a VR portal metaphor, a scenario relevant for studying sensory compensation in the brain [24].

- Apparatus and Sensory Devices: Use a commercial VR headset with integrated head-tracking. Attach an olfactory device to the bottom of the head-mounted display (HMD) to deliver scents instantly with controlled ventilation. Use integrated or external headphones for auditory cues [24].

- Task and Experimental Design: Present participants with four distinct portals, each offering a narrow field of view into a remote scene (e.g., a kitchen, garden). Assign each portal a unique combination of sensory cues (visual, auditory, olfactory). The participant's task is to identify a target scene, described via text, by selecting the correct portal from the alternatives [24].

- Sensory Conditions: Employ a within-subjects design where each participant is tested under multiple sensory conditions in a randomized order:

- Visual-only (control)

- Visual + Auditory

- Visual + Olfactory

- Visual + Auditory + Olfactory [24]

- Data Collection: Measure the accuracy of portal selection and the response time for each trial. Analyze the data to determine the specific contribution of each sensory modality to recognition performance [24].

Theoretical Models and Research Paradigms

The application of VR in multisensory brain research is guided by several key theoretical models from cognitive psychology and HCI.

- Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning: This theory proposes that people learn more effectively from words and pictures than from words alone, and that learning is an active process of filtering, selecting, organizing, and integrating information. In a VR context, it suggests that multisensory instruction (e.g., VR combined with scent) can lead to improved learning outcomes, though the cognitive load must be managed to avoid overwhelming the learner [25].

- The Plausibility and Placement Illusions: IVR systems create a "plausibility illusion" (the belief that the events in the VR are really happening) and a "placement illusion" (the feeling of "being" in the virtual environment). These illusions are crucial for eliciting naturalistic behaviors and are enhanced by the integration of proprioceptive, visual, and motor information, engaging the sensorimotor system more fully than screen-based systems [23].

- Cross-Modal Compensation and Plasticity: In the absence of one sense, the brain demonstrates neuroplasticity by reorganizing and enhancing the processing of remaining senses. Studies on visually impaired individuals show that auditory and tactile cues can be used to perform complex interceptive actions, such as catching a ball. This principle underpins rehabilitation strategies that leverage multisensory training to restore visual function by harnessing brain plasticity [26] [27].

Visualization of Research Paradigms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key technologies and materials required for constructing multisensory VR experiments for brain research.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Multisensory VR Experiments

| Item / Technology | Function / Application in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Headset (HMD) | Displays the virtual environment; provides head-tracking for updating the visual perspective and creating immersion [23]. | Choose based on field of view, resolution, refresh rate, and built-in audio. Integral for creating the "placement illusion" [23]. |

| Olfactory Delivery Device | Presents controlled, congruent olfactory stimuli to participants during VR exposure [24]. | Devices can use vapor diffusion or heating of solid/liquid materials. Key design aspects include scent type, intensity, spatial origin, and timing [24]. |

| Haptic Controllers / Gloves | Provides tactile feedback and enables naturalistic motor interaction with virtual objects, engaging the sensorimotor system [23]. | Enhances the "plausibility illusion" and supports the study of motor control and object interaction [23]. |

| Spatial Audio System | Delivers realistic, directionally accurate sound cues that enhance spatial awareness and contextual realism [24]. | Critical for auditory compensation paradigms and for studying spatial perception in visually constrained environments [24] [27]. |

| Biometric Sensors (EEG, EDA) | Measures physiological correlates of cognitive and emotional states (e.g., attention, engagement, stress) during VR tasks [5]. | Affective EEG indicators can provide empirical evidence of emotional engagement linked to cognitive performance [5]. |

| Cognitive Assessment Batteries | Validated questionnaires and scales to measure pre- and post-intervention changes in specific cognitive domains [5]. | Includes tests for memory, attention, executive function, and spatial orientation. Essential for quantifying cognitive outcomes [23] [5]. |

The integration of Information Systems, HCI, and Cognitive Psychology provides a powerful, interdisciplinary framework for advancing brain research using multisensory VR. Current evidence confirms that thoughtfully designed multisensory VR interventions can enhance specific cognitive functions, including memory, spatial awareness, and creativity, by leveraging principles of brain plasticity and multisensory integration [22] [26] [5]. Future research should focus on refining these interventions, exploring the underlying neural mechanisms via neuroimaging, and developing more accessible and culturally relevant applications to enhance sensory compensation and cognitive recovery across diverse populations [22] [26] [27]. For drug development professionals, these VR paradigms offer robust, ecologically valid tools for assessing the cognitive impacts of pharmacological agents in controlled yet realistic environments.

From Lab to Clinic: VR Platforms and Their Research Applications

Virtual reality (VR) offers an unprecedented tool for neuroscience research, enabling the controlled presentation of complex, ecologically valid stimuli to study multisensory integration in the brain. For researchers investigating the neural mechanisms of sensory processing, the technical fidelity of these platforms is paramount. The core challenge lies in ensuring temporal and spatial coherence across sensory modalities—a prerequisite for generating valid, reproducible neural data. This technical guide outlines the foundational principles, validation methodologies, and experimental protocols for designing multisensory VR platforms suited for rigorous neuroscientific inquiry and drug development applications.

The integration of sensory information is a time-sensitive process. The brain leverages temporal windows of integration, where stimuli from different senses are bound into a unified percept if they occur in close temporal proximity [28]. Similarly, spatial coincidence provides a critical cue for inferring a common source for auditory, visual, and tactile events. VR systems used for research must therefore achieve a high degree of precision and accuracy in controlling these parameters to effectively simulate realistic multisensory events and study the underlying brain mechanisms [29] [30].

Theoretical Foundations of Multisensory Coherence

Temporal Structure and Processing Across Senses

The perception of temporal structure is fundamental to multisensory integration. Research reveals that humans can perceive rhythmic structures, such as beat and metre, across audition, vision, and touch, albeit with modality-specific limitations [28]. The temporal discrimination thresholds—the ability to perceive two stimuli as separate—vary significantly between senses:

- Audition: Gap detection thresholds are as low as 2-3 ms for clicks, making it the most temporally acute sense.

- Vision: Temporal resolution is lower than audition, impacting the perception of rapid sequential stimuli.

- Touch: Temporal acuity falls between that of vision and audition [28].

This hierarchy establishes auditory dominance in temporal processing, meaning that auditory cues can often influence the perceived timing of visual or tactile stimuli in crossmodal contexts [28]. This has direct implications for designing VR experiments; for instance, auditory stimuli may need to be deliberately delayed to achieve perceived simultaneity with visual events.

Spatial Perception in Virtual Environments

Spatial perception in VR is fundamentally shaped by the system's level of immersion. A key distinction exists between fully immersive Virtual Reality Interactive Environments (IVRIE) and semi-immersive, desktop-based (DT) systems [30]. IVRIE systems, which use head-mounted displays (HMDs) and motion tracking, provide a sense of presence and direct interaction that enhances a user's understanding of scale, volume, and spatial relationships [30]. This is critical for research, as the level of immersion can significantly impact the ecological validity of the study and the resulting neural and behavioral data.

Technical Implementation of Coherent Stimuli