Neural Mechanisms of Cognitive Reserve: From Brain Networks to Therapeutic Interventions

This comprehensive review examines the neural implementation of cognitive reserve (CR) and its implications for maintaining brain performance against aging and neurodegeneration.

Neural Mechanisms of Cognitive Reserve: From Brain Networks to Therapeutic Interventions

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the neural implementation of cognitive reserve (CR) and its implications for maintaining brain performance against aging and neurodegeneration. We synthesize current research on the neurobiological substrates of CR, including brain network redundancy, functional connectivity patterns, and compensatory activation. The article explores methodological approaches for quantifying CR through neuroimaging and behavioral proxies, addresses conceptual challenges in the field, and validates CR metrics through their predictive value for cognitive outcomes. For researchers and drug development professionals, we highlight how understanding CR mechanisms can inform clinical trial design and therapeutic development for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, with particular focus on the evolving drug pipeline and biomarker development.

Unraveling the Neurobiological Basis of Cognitive Reserve

The concept of reserve emerged from a consistent clinical observation: a striking disjunction between the degree of brain pathology and its resulting clinical and cognitive manifestations. This whitepaper traces the evolution of this concept from its origins in epidemiological and neuropathological findings to our current, more nuanced understanding of the active neural mechanisms that underlie it. We detail how initial, passive models of "brain reserve" have been supplemented by active models of "cognitive reserve," and review the burgeoning evidence for the critical role of neuroglia in establishing this reserve. Framed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document provides a comprehensive overview of the theoretical models, key experimental evidence, methodological approaches, and potential interventional targets that define the modern science of reserve.

The field of reserve originated from a universally acknowledged truth in neurology: the functional consequences of brain damage are highly individual and often out of joint with the degree of injury [1]. The same structural damage to the brain—whether from trauma, ischemia, or neurodegenerative disease—leads to widely different neurological and cognitive outcomes in different patients [1]. This discrepancy is perhaps most starkly illustrated in Alzheimer's disease (AD), where post-mortem examinations have revealed individuals with significant AD pathology (e.g., high plaque counts) who demonstrated preserved memory and intelligence prior to death [1]. Conversely, approximately one-third of unimpaired elderly individuals were found to meet full pathological criteria for AD upon post-mortem examination [1] [2]. This paradox highlighted that some brains possess a inherent capacity to withstand insult and provide functional compensation, a capacity that is now understood to reflect the lifelong interaction of genetic factors and environmental exposures, or the exposome [1]. The following sections delineate the journey from observing this paradox to elucidating its underlying mechanisms.

The Evolution of Theoretical Models

Theoretical models to explain the clinical paradox have evolved from simple, passive threshold models to complex, active frameworks involving dynamic neural processes.

From Brain Reserve to Cognitive Reserve

The earliest models sought to explain reserve in passive, anatomical terms.

Brain Reserve (BR): The passive model of reserve posits that structural characteristics of the brain, such as its size, the number of neurons, or synaptic count, provide resilience [3] [4] [2]. An individual with a larger brain reserve can theoretically absorb more damage before a critical threshold is crossed and clinical deficits emerge [2] [5]. This model is often analogized as the "hardware" of the brain [4].

Cognitive Reserve (CR): In contrast, the active model of cognitive reserve posits that the brain actively copes with damage by using pre-existing cognitive processes or enlisting compensatory ones [3] [4] [2]. CR reflects the brain's ability to improvise and find alternate ways to complete tasks, emphasizing the flexibility, efficiency, and capacity of brain networks [6] [5]. This is considered the "software" of the brain [4].

Table 1: Key Conceptual Models of Reserve

| Model | Core Principle | Mechanism | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Reserve (BR) | Passive, structural capacity | More neurons/synapses provide a higher threshold for symptom onset. | [3] [2] |

| Cognitive Reserve (CR) | Active, functional adaptability | Efficient, flexible, or compensatory use of brain networks. | [3] [4] [2] |

| Brain Maintenance | Preservation of brain integrity over time | Reduced development of age-related brain changes or pathology. | [3] [5] |

| Scaffolding (STAC) | Compensatory neural scaffolding | Recruitment of additional neural circuits to support declining functions. | [3] |

Modern Conceptual Frameworks

Recent consensus has refined these concepts into a multi-component framework, which includes:

- Brain Reserve: The structural characteristics of the brain at a given point in time [3].

- Brain Maintenance: The process of maintaining brain structure and resisting pathology over time, influenced by genetics and life experiences [3] [4] [5].

- Cognitive Reserve (Resilience): The adaptability of cognitive processes that allows for better coping with existing brain pathology [3].

- Compensation: The recruitment of alternative neural processes or networks to maintain performance in the face of high cognitive demand or brain damage [1] [3].

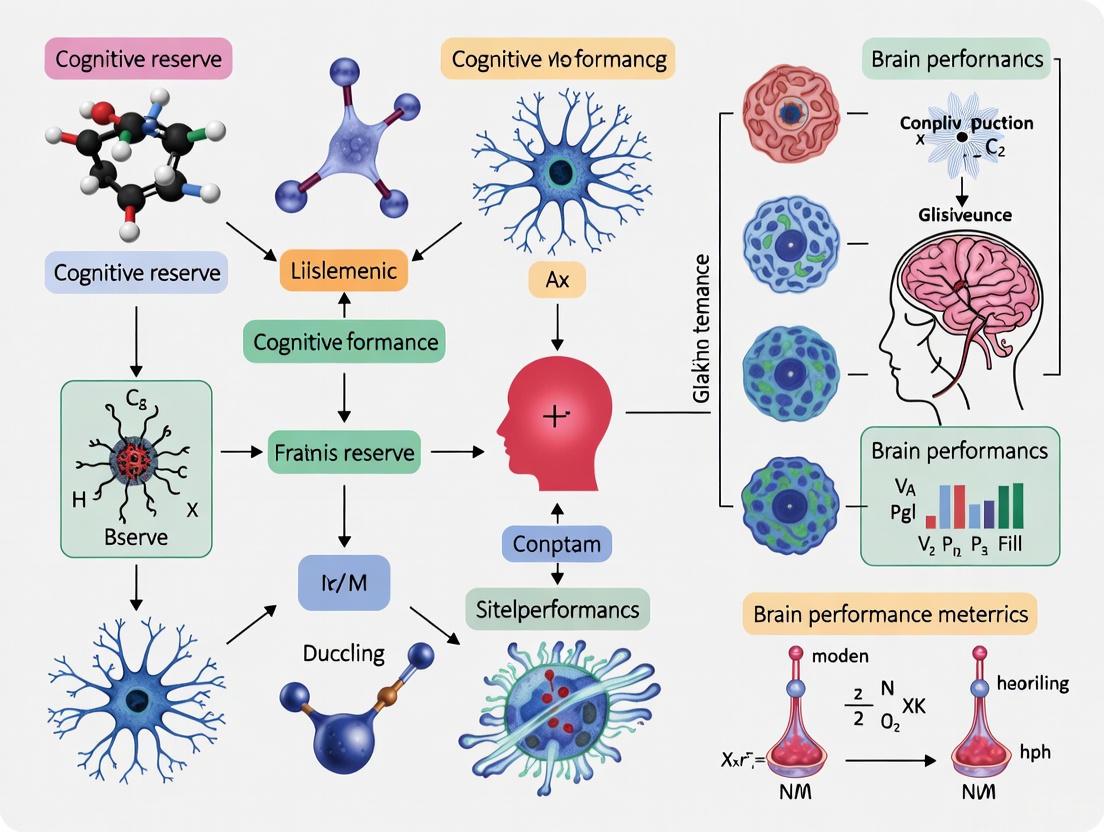

These components collectively operate throughout the lifespan to provide resilience against brain aging and disease [3]. The relationship between these concepts is illustrated below.

Quantitative Evidence and Epidemiological Foundations

The reserve hypothesis is supported by extensive epidemiological data showing that specific lifetime experiences are associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

Key Proxy Measures of Cognitive Reserve

As a latent construct, CR cannot be measured directly and is typically inferred through proxy variables that reflect lifetime exposures and cognitive enrichment [3] [4] [2]. The most commonly used proxies include:

- Educational Attainment: Higher levels of formal education are consistently linked to a lower risk of dementia [2] [7].

- Occupational Complexity: Jobs that involve complex tasks with data or people are associated with greater CR [2].

- Engagement in Leisure Activities: Late-life engagement in cognitively, socially, and physically stimulating activities contributes to reserve [3] [6].

- Premorbid IQ / Literacy: Estimates of innate intelligence or literacy levels can be powerful measures of reserve, sometimes more so than years of education [2].

Impact on Cognitive Outcomes and Disease Trajectory

Longitudinal studies have quantified the protective effect of these proxies. A seminal 1994 study found that the relative risk (RR) of developing dementia was 2.2 times higher in individuals with less than 8 years of education and 2.25 times higher in those with low occupational attainment [2]. Furthermore, CR does not just delay onset; it also alters the trajectory of decline. Stern's model hypothesizes that individuals with high CR can sustain more pathology before showing symptoms, but once their compensatory capacity is exhausted, they may experience a faster subsequent rate of decline [3] [7].

Table 2: Epidemiological Evidence for Cognitive Reserve Proxies

| Proxy Variable | Study Findings | Effect Size / Risk Ratio | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Reduced risk of incident dementia | RR = 2.2 (Low vs. High Education) | [2] |

| Occupational Attainment | Reduced risk of incident dementia | RR = 2.25 (Low vs. High Occupation) | [2] |

| CR Composite (Education, Reading, Vocabulary) | Interaction with cortical thickness on risk of MCI symptom onset >7 years post-baseline | Significant Interaction Effect (p < .05) | [8] |

| Education in YOAD | Predicts greater cognitive decline in the first year after diagnosis | Faster MMSE decline (β significant) | [7] |

Unveiling the Mechanisms: The Neural Implementation of Reserve

A primary goal of modern research is to move from proxies to direct measures of the neural substrates that implement reserve, often termed "neural reserve" and "neural compensation" [4] [2].

Neuroglial Mechanisms in Focus

Historically, a neuron-centric view dominated, but recent perspectives argue that neuroglia are fundamental for defining cognitive reserve [1]. Glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendroglia, and microglia) contribute to CR through several vital pathways:

- Shaping Brain Reserve: Astrocytes regulate synaptogenesis and synaptic pruning, while oligodendroglia support the brain-wide connectome through myelination, directly influencing the number and efficiency of neuronal connections [1].

- Ensuring Brain Maintenance: Astrocytes are the main homeostatic cells of the CNS, regulating ionostasis, neurotransmitter clearance, and providing the primary antioxidant system, thereby preserving the physiological environment necessary for robust neural function [1].

- Enabling Compensation: In response to pathology, neuroglia mount protective and regenerative responses, including neuroprotection and potentially supporting the repair of damaged circuits [1].

Functional and Structural Neural Correlates

Neuroimaging studies have identified specific brain patterns associated with higher CR:

- Neural Reserve: This refers to inter-individual differences in the efficiency, capacity, or flexibility of brain networks in healthy individuals [4] [2]. For example, individuals with higher IQ (a CR proxy) show more efficient task-related brain activation, requiring less neural effort for the same level of performance [4].

- Neural Compensation: This involves the recruitment of additional or alternative brain networks to maintain performance in the face of challenge or damage [2]. This may manifest as the bilateral recruitment of homologous brain areas in older adults or patients, whereas younger adults use more focal, unilateral regions [3].

The following diagram synthesizes the core experimental paradigm and key findings used to investigate the neural correlates of reserve.

Experimental Approaches and the Scientist's Toolkit

Research into reserve leverages a multimodal approach, combining epidemiological designs with advanced neuroimaging and neurophysiological techniques.

Core Methodological Paradigms

Key experimental designs include:

- Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Tracking cognitively normal individuals over time to identify factors that predict progression to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or dementia. The BIOCARD study is a prime example, where baseline cortical thickness and CR proxies predicted risk of clinical symptom onset over a decade later [8].

- Cross-Sectional fMRI Studies: Comparing brain activation patterns during cognitive tasks between groups with high and low CR proxies, matched for performance, to identify neural correlates of efficiency or compensation [4].

- Residual Approach: Statically defining CR as the variance in cognitive performance not explained by measured brain pathology or demographics [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and methodological tools for investigating reserve in experimental models and human studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reserve Mechanism Investigation

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use in Reserve Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structural MRI | Quantifies brain morphology (volume, cortical thickness). | Measure baseline brain reserve (e.g., hippocampal volume) and track brain maintenance via atrophy rates [8]. |

| Task-Based fMRI | Maps brain activity during cognitive tasks. | Identify neural reserve (efficiency) and compensation (alternative networks) by comparing activation in high vs. low CR groups [4]. |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) | Assesses white matter integrity and structural connectivity. | Examine the integrity of the brain's "wiring" as a component of brain reserve and its role in network efficiency [4]. |

| Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (NIBS) | Modulates and probes cortical excitability and plasticity. | Investigate causal mechanisms of compensation and motor reserve; potentially enhance plasticity to boost reserve [9]. |

| Amyloid/Tau PET Imaging | In vivo detection of Alzheimer's pathology. | Correlate pathology burden with cognitive performance in individuals with varying CR levels to test the CR hypothesis [3]. |

| Virtual Reality (VR) Navigation Tasks | Assesses spatial memory and navigation in ecologically valid environments. | Cross-species translational studies (e.g., water maze in rodents to VR in humans) to link hippocampal function to cognitive outcomes [5]. |

Implications for Intervention and Drug Development

The reserve framework offers promising, non-pharmacological avenues for maintaining cognitive health and provides critical context for evaluating pharmacological interventions.

- Lifestyle Interventions: Research supports a multi-faceted approach to building reserve, including cognitive stimulation (lifelong learning, challenging the brain), physical exercise (which promotes neurogenesis and upregulates BDNF), and diet and stress management [2] [6]. The Harvard Medical School model identifies six cornerstones: a plant-based diet, regular exercise, adequate sleep, stress management, social contact, and continued mental challenge [6].

- Considerations for Clinical Trials: The CR theory has a crucial implication for drug development: individuals with high CR may be diagnosed later in their disease course when pathology is more severe [7]. Therefore, clinical trials must account for CR proxies as confounding variables, as they can influence both the baseline severity and the rate of decline, potentially masking or exaggerating a drug's effect.

The journey from the initial observation of a pathology-cognition discrepancy to the mechanistic understanding of reserve has transformed our approach to brain aging and disease. The origin of the reserve concept lies in recognizing the brain not as a static organ, but as a dynamic system shaped by a lifetime of experiences. The evolution from passive brain reserve to active cognitive reserve and compensation models highlights the importance of network flexibility and neuroglial function. For researchers and drug developers, this paradigm underscores the necessity of accounting for reserve in study designs and points to a future where interventions—both pharmacological and lifestyle-based—are specifically targeted at enhancing the brain's inherent resilient capacities.

The constructs of brain reserve and cognitive reserve serve as critical frameworks for explaining the marked individual differences observed in cognitive outcomes following brain aging, injury, or disease. Significant individual differences exist in the trajectories of cognitive aging and in age-related changes of brain structure and function, with some individuals exhibiting significant pathological brain changes alongside relatively preserved cognitive performance [5]. This observed disjunction between the degree of objective brain damage and its clinical manifestations has prompted the development of reserve theory to account for why individuals with similar brain pathology can experience dramatically different cognitive outcomes [2]. The reserve concept has gained substantial scientific attention across neurodegenerative diseases, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and other neurological conditions [10].

At its core, the distinction between brain and cognitive reserve can be conceptualized through a computer analogy: brain reserve represents the brain's structural "hardware" - its physical and anatomical properties - while cognitive reserve corresponds to the brain's functional "software" - the dynamic processes and network operations that enable cognitive performance [5] [11]. This hardware/software distinction provides a useful heuristic for understanding the complementary protective mechanisms that allow some individuals to maintain cognitive function despite substantial neuropathology.

This whitepaper examines the neural mechanisms underlying these reserve constructs, focusing on their distinction, measurement, and implications for therapeutic development. We synthesize current research from neuroimaging, epidemiological, and animal model studies to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical framework for understanding cognitive resilience.

Theoretical Frameworks and Distinguishing Features

Brain Reserve: The Passive Threshold Model

Brain reserve (BR) constitutes a passive model of resilience based on the quantitative structural properties of the brain [2] [10]. This model posits that individual differences in brain anatomy—such as brain size, neuronal count, or synaptic density—create variation in the amount of brain damage that can be sustained before clinical deficits emerge [5] [1]. The BR model operates on a threshold principle, wherein cognitive impairment manifests only when brain damage depletes reserve capacity beyond a critical level [2]. In this framework, the brain is viewed as a passive container of neural resources, with larger brains presumably possessing more capacity to withstand pathology before crossing the threshold into impairment [11].

The passive nature of BR does not imply immutability. Life experiences can influence brain anatomy through neurogenesis, angiogenesis, promoting resistance to apoptosis, and up-regulating compounds that promote neural plasticity [2]. However, the protective mechanism remains fundamentally quantitative—individuals with greater initial brain reserve can tolerate more neuropathology in absolute terms before clinical symptoms emerge [5].

Cognitive Reserve: The Active Processing Model

In contrast to BR, cognitive reserve (CR) represents an active model of resilience based on the brain's dynamic functional capabilities [5] [2]. CR theory posits that individual differences in how cognitive tasks are processed—including the efficiency, capacity, or flexibility of cognitive networks—allow some people to better cope with brain pathology [2]. Rather than merely providing a larger buffer of neural tissue, CR enables active compensation for brain damage through the use of pre-existing cognitive processes or the enlistment of alternative neural networks [2] [10].

The active nature of CR manifests through two primary neural mechanisms: neural reserve and neural compensation [2]. Neural reserve refers to inter-individual variability in the functioning of brain networks engaged by healthy individuals when performing cognitive tasks. These networks may differ in their efficiency, capacity, or flexibility, creating differential vulnerability to disruption. Neural compensation refers to the recruitment of alternative brain networks or cognitive strategies not typically used by individuals with intact brains, which may help maintain performance despite neuropathological disruption [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Brain Reserve and Cognitive Reserve

| Feature | Brain Reserve | Cognitive Reserve |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Passive, quantitative | Active, qualitative |

| Analogy | Hardware | Software |

| Mechanism | Threshold model | Adaptive processing |

| Primary Measures | Brain volume, cortical thickness, synaptic density | Education, occupation, IQ, leisure activities |

| Neural Basis | Structural properties | Network efficiency & compensation |

| Theoretical Foundation | Satz (1993) threshold model | Stern (2002) active model |

Measurement Approaches and Neurobiological Correlates

Assessing Brain Reserve

BR is typically quantified through direct and indirect measures of brain structure. Direct measures include brain volume (global and regional), cortical thickness, synaptic density, and white matter integrity [10] [12]. Indirect structural proxies include head circumference and total intracranial volume, which serve as estimates of premorbid brain size [10]. These measures are often derived from structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, with automated processing pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer) enabling precise quantification of volumetric and thickness parameters [12].

In clinical research, BR measures have demonstrated protective effects across various conditions. For example, a study of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) outcomes found that a larger baseline cortical thickness of memory-related regions (parahippocampal gyrus and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex) correlated with less autobiographical memory decline following treatment [12]. Similarly, research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has used the predicted age difference (PAD) between brain age estimated from MRI and chronological age as a BR proxy, with younger-appearing brains conferring protection against cognitive impairment [13].

Quantifying Cognitive Reserve

As a latent construct, CR cannot be measured directly but is typically assessed through proxy variables that reflect life experiences theoretically contributing to reserve [5] [2]. Common proxies include:

- Educational attainment (years of education or degree obtained)

- Occupational complexity (cognitive demands of work)

- Leisure activities (cognitive, social, and physical activities)

- Premorbid IQ (often estimated through vocabulary tests)

- Social engagement (breadth and depth of social networks)

These proxies are often combined into composite indices, such as the Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq), which integrates education, working activity, and leisure time [14]. In research settings, CR is also operationalized through cognitive tests that measure executive function, processing speed, or memory performance [14].

Neuroimaging studies have identified potential neural implementations of CR, including patterns of brain activation that are expressed to a greater degree in individuals with higher IQ [5]. Furthermore, functional MRI studies suggest that individuals with higher CR proxies may maintain cognitive performance despite brain pathology through more efficient use of existing networks or compensatory recruitment of additional brain regions [5] [2].

Table 2: Measurement Approaches for Reserve Constructs

| Reserve Type | Direct Measures | Proxy Measures | Imaging Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Reserve | Brain volume, cortical thickness, synaptic density, white matter integrity | Head circumference, intracranial volume | Larger volume in specific regions (e.g., hippocampus, prefrontal cortex) |

| Cognitive Reserve | Neural efficiency, network capacity, compensation ability | Education, occupation, IQ, leisure activities | Differential brain activation patterns, functional connectivity |

Experimental Evidence and Research Paradigms

Epidemiologic and Clinical Studies

Substantial epidemiologic evidence supports the protective role of both BR and CR against cognitive decline and dementia. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that individuals with higher levels of CR proxies (education, occupational attainment, leisure activities) have a reduced risk of developing dementia and slower rates of age-related cognitive decline [5] [2]. A recent meta-analysis of 27 longitudinal studies found that CR accumulated across the entire lifespan—early-life (HR: 0.82), middle-life (HR: 0.91), and late-life (HR: 0.81)—has protective effects on dementia risk [15].

The protective mechanism of CR is further supported by studies showing that individuals with higher CR proxies can withstand more advanced Alzheimer's pathology while maintaining cognitive function. For example, highly educated patients with Alzheimer's disease show more advanced pathology (Aβ plaques, tau tangles) at the same level of cognitive impairment as less educated patients, suggesting that CR helps them cope with pathology more effectively [5] [10].

Neuroimaging Evidence

Advanced neuroimaging techniques have provided insights into the neural mechanisms underlying reserve. Studies utilizing structural MRI have established that larger brain volume and greater cortical thickness in specific regions are associated with better cognitive outcomes following brain insult or in neurodegenerative diseases [12] [13].

Functional MRI studies reveal that CR proxies moderate the relationship between brain pathology and cognitive performance. Individuals with higher CR may display more efficient processing (less brain activation for the same level of performance) or compensatory recruitment of alternative networks (different activation patterns) when confronting cognitive challenges [5] [2]. For instance, our group has identified a pattern of brain activation that occurs during task performance that is expressed more strongly in people with higher IQ, and expression of this pattern moderates the relationship between age-related brain changes and performance [5].

Animal Models

Animal research has contributed significantly to understanding reserve mechanisms by enabling detailed investigation of molecular and cellular processes. Studies in aging rodents have demonstrated that individual differences in cognitive aging occur without significant neuron loss, pointing to the importance of synaptic plasticity and connectivity rather than sheer cell numbers [5]. Animal research has been particularly valuable for examining how life experiences (environmental enrichment, physical activity) promote neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and resistance to pathology—thereby enhancing both brain and cognitive reserve [5] [1].

Experimental Protocols for Reserve Research

Structural MRI Protocol for Brain Reserve Assessment

Objective: To quantify structural brain reserve proxies including regional brain volumes, cortical thickness, and white matter integrity.

Methodology:

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical scans using magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence with the following parameters: 256 × 256 image matrix with 192 sagittal slices, FOV 250 × 250×192mm, voxel size 1 × 1×1mm³, echo time 4.82ms, repetition time 2500ms, and flip angle 7° [13].

- Image Processing: Process T1- and T2-weighted images automatically in FreeSurfer using the longitudinal stream. Perform cortical parcellation using the Desikan-Kiliany and Destrieux atlases. Conduct hippocampal segmentation using the hippocampal module [12].

- Quality Control: Perform visual inspection of coronal slices to ensure correct delineation of boundaries between gray and white matter. Exclude or manually correct slices with poor segmentation.

- Regional Analysis: Extract volume and thickness measurements for pre-determined regions of interest (ROIs) including hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex, and angular gyrus [12].

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct partial correlation analyses between ROI measures and cognitive outcomes, controlling for appropriate covariates (e.g., age, sex, intracranial volume).

Cognitive Reserve Proxy Assessment Protocol

Objective: To create a composite cognitive reserve index integrating multiple life experience proxies.

Methodology:

- Participant Assessment:

- Educational attainment: Record years of formal education and highest qualification obtained. Convert to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) levels [13].

- Occupational history: Administer structured interview to document all paid employment held by participant. Classify occupations by cognitive demands and responsibility levels [14].

- Leisure activities: Adminisure the Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq) leisure time subscale to document engagement in cognitively stimulating activities outside work hours [14].

- Premorbid intelligence: Assess verbal intelligence using standardized tests such as the WAIS-IV Vocabulary subtest, which remains relatively stable despite neurological disease progression [13].

Data Integration:

- Normalize scores for each proxy measure (education, occupation, leisure, IQ) to z-scores.

- Calculate composite CR score as the mean of standardized scores for all available proxies [13].

- Alternatively, use validated CR algorithms such as the CRIq scoring system which provides total and subscale scores [14].

Validation: Examine association between CR composite score and cognitive outcomes in relevant clinical populations, controlling for demographic variables and brain pathology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodologies and Reagents for Reserve Research

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument/Reagent | Application in Reserve Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | 3T MRI Scanner with 32-channel head coil | High-resolution structural imaging for BR assessment | Ensure consistent acquisition parameters across study sites |

| Image Processing | FreeSurfer longitudinal stream (v7.4.1+) | Automated cortical parcellation and volumetric measurement | Use Desikan-Killiany and Destrieux atlases for ROI analysis |

| Cognitive Assessment | WAIS-IV Vocabulary subtest | Proxy for premorbid intelligence | Relatively stable in neurodegenerative diseases |

| CR Quantification | Cognitive Reserve Index (CRIq) | Standardized assessment of education, occupation, and leisure | Provides total score and three sub-dimension scores |

| Lifestyle Assessment | Lifestyle for Brain Health (LIBRA) | Evaluation of modifiable risk and protective factors | Scores range from -5.9 to +12.7; higher scores indicate higher dementia risk |

| Statistical Analysis | BrainAgeR algorithm (v2.1+) | Estimation of brain age gap as BR proxy | Trained on n=3377 healthy adults; validated on 857 people |

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms

The Emerging Role of Neuroglia

Traditionally, research on reserve mechanisms has focused on neuronal changes. However, emerging evidence highlights the fundamental contribution of neuroglial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia) to both brain and cognitive reserve [1]. Astrocytes support BR through regulating synaptogenesis, synaptic maturation, and synaptic extinction [1]. Microglia contribute by removing redundant or malfunctioning synapses through synaptic pruning, thereby shaping neuronal ensembles [1]. Oligodendrocytes support the brain-wide connectome through activity-dependent myelination, with white matter accounting for approximately 50% of the adult human brain and representing a key determinant of cognitive abilities [1].

Beyond their role in BR, neuroglia are crucial for brain maintenance—the homeostatic processes that preserve brain physiology throughout life. Astrocytes regulate ionostasis through dedicated pumps and transporters, control neurotransmission through neurotransmitter clearance and catabolism, and provide neuroprotection through multiple pathways including antioxidant systems [1]. These glial mechanisms represent promising targets for interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive reserve and resilience.

Network Control Theory Applications

Dynamic network theory provides a novel framework for understanding reserve mechanisms at the systems level. Network control theory—an engineering-based approach—examines how the brain's structural architecture constrains its functional dynamics and capacity to transition between cognitive states [11]. From this perspective, BR represents the structural substrate (nodes and connections), while CR reflects the efficiency and flexibility of dynamic processes operating on that substrate [11].

This theoretical framework suggests that individuals with higher CR may have brain networks that are more controllable—requiring less energy to transition between cognitive states—or more resilient to structural damage. Such network-level approaches offer promising directions for quantifying reserve mechanisms and developing targeted interventions to enhance cognitive resilience in aging and disease [11].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The distinction between brain and cognitive reserve has significant implications for therapeutic strategies targeting cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacological approaches may preferentially enhance BR by promoting neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, or white matter integrity, while behavioral interventions may primarily boost CR by enhancing network efficiency and compensatory capacity [1]. The most effective approaches will likely combine both strategies, recognizing that BR provides the structural substrate upon which CR operates.

Future therapeutic development should consider several key principles derived from reserve research. First, interventions should begin early in life, as reserve accumulates across the entire lifespan [15]. Second, multidomain approaches addressing multiple reserve proxies simultaneously may prove more effective than single-focus interventions [14]. Third, personalized approaches that account for individual differences in existing reserve capacity may optimize outcomes. Finally, combining pharmacological agents that enhance BR with cognitive training that builds CR may produce synergistic benefits for maintaining cognitive health in aging and disease.

For drug development professionals, reserve constructs offer valuable intermediate endpoints for clinical trials. Measures of brain structure (cortical thickness, hippocampal volume) and functional network characteristics may detect treatment effects before cognitive changes become apparent, potentially accelerating therapeutic development. Furthermore, assessing baseline reserve in trial participants may help identify subgroups most likely to benefit from specific interventions, enabling more targeted and efficient clinical development programs.

The quest to understand the neural implementation of complex cognitive functions necessitates a deep exploration of the core principles governing neural networks: efficiency, capacity, and flexibility. These principles are not only fundamental to the operation of biological neural circuits but also provide a crucial framework for understanding cognitive phenomena such as cognitive reserve, which describes the brain's resilience to age-related changes or pathology. In the brain, efficiency refers to the optimal use of metabolic and biophysical resources to perform computations. Capacity defines the limits of information storage and processing within a neural system, while flexibility is the ability to dynamically adapt processing strategies in response to changing task demands or environmental contingencies. This technical guide synthesizes recent advances from computational neuroscience, systems biology, and clinical research to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these three pillars of neural function, framing them within the context of cognitive reserve and brain performance research. By integrating quantitative modeling, experimental data, and theoretical frameworks, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for understanding the neural implementations that balance these often-competing demands.

Quantitative Frameworks for Assessing Neural Network Properties

Effective Model Complexity (EMC) as a Capacity Metric

A critical metric for quantifying the functional capacity of neural networks is the Effective Model Complexity (EMC). Unlike mere parameter counts, EMC empirically measures the largest sample size that a model can perfectly fit using standard training procedures. The calculation of EMC involves an iterative approach where a model is trained on a small number of samples. If 100% training accuracy is achieved, the process is repeated with a larger, independently sampled set. This continues until the model can no longer perfectly fit the training data, with the largest successful sample size defining the network's EMC [16].

Quantitative studies using EMC have yielded key insights into the practical capacity of neural networks. Standard optimizers typically find minima where models can only fit training sets with significantly fewer samples than the total number of parameters. Furthermore, architectural choices profoundly impact parameter efficiency; convolutional networks (CNNs) demonstrate greater parameter-efficiency than multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs), even on randomly labeled data. This suggests that CNNs' superior generalization stems not only from better inductive biases but also from inherently superior capacity utilization. The training algorithm itself also shapes effective capacity; surprisingly, SGD finds minima that fit more training data than full-batch gradient descent, contrary to the common belief that SGD's regularizing effect necessarily reduces capacity [16].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Effective Model Complexity (EMC) in Neural Networks

| Factor | Impact on EMC | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Convolutional networks are more parameter-efficient than MLPs and ViTs | Testing on correctly and randomly labeled data [16] |

| Optimizer | SGD finds minima with higher EMC than full-batch gradient descent | Comparison of training dynamics and final solutions [16] |

| Activation Function | ReLU enables fitting more samples than sigmoidal activations | Ablation studies across architectures [16] |

| Data Labeling | Networks fit more correctly labeled than incorrectly labeled samples | Differential capacity predictive of generalization [16] |

Landscape and Flux Theory for Flexibility and Efficiency

From a biophysical perspective, neural circuits operate as non-equilibrium systems, requiring a framework that incorporates energy flow and stability. The non-equilibrium landscape and flux theory provides a quantitative approach to understanding the interplay between accuracy and flexibility in cognitive functions like decision-making (DM) and working memory (WM). This framework quantifies the underlying attractor landscapes—mathematical representations of the stability of different neural activity patterns—and the flux that drives transitions between them [17].

In this framework, the "potential" is an effective landscape that visualizes system dynamics, where stable states (attractors) correspond to particular cognitive states (e.g., a memory representation or a decision outcome). The depth of an attractor basin determines the stability of a state, while the height of barriers between basins determines the flexibility to switch states. Crucially, this effective potential is distinct from the actual metabolic energy consumption, which is quantified separately through the entropy production rate, serving as a proxy for thermodynamic costs associated with maintaining and transitioning between neural states [17].

This approach reveals fundamental trade-offs: neural circuit architectures with selective inhibition create stronger resting states that improve DM accuracy but result in weaker decision states that are less robust to distractors. This creates a tension between stability and flexibility. Computational studies show that presenting a ramping non-selective input during the delay period of DM tasks can act as a temporal gating mechanism, enhancing WM robustness against distractors with minimal increase in thermodynamic cost compared to constant non-selective inputs [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics in Neural Landscape and Flux Theory

| Metric | Definition | Cognitive Correlate |

|---|---|---|

| Basin Depth | Stability measure of an attractor state | Robustness of working memory against distraction [17] |

| Barrier Height | Energy barrier between attractor states | Flexibility in switching decisions or memories [17] |

| Entropy Production Rate | Proxy for thermodynamic cost of neural computation | Metabolic efficiency of cognitive operations [17] |

| Perturbation Sensitivity | Rate of transition between states under noise | Vulnerability to interference or distractors [17] |

Neural Mechanisms of Cognitive Reserve and Brain Performance

Reserve Constructs and Their Neural Implementation

The concepts of network efficiency, capacity, and flexibility find direct application in the clinical neuroscience of cognitive reserve (CR) and brain reserve (BR). These constructs explain the observed discrepancy between brain pathology and clinical manifestation, where individuals with higher reserve maintain cognitive function despite significant age-related or pathological brain changes [5].

Brain reserve represents a passive, "hardware" model of reserve, conceptualized as individual differences in neuroanatomical resources such as brain size, neuronal count, and synaptic density. In this model, a larger initial reserve allows the brain to tolerate more neurological attrition before crossing a threshold into functional impairment [5] [13]. In contrast, cognitive reserve is an active, "software" model, positing individual differences in the flexibility, efficiency, and adaptability of cognitive/brain networks that allow active compensation for brain damage through alternative network strategies [5].

Neuroimaging evidence supports the neural implementation of these reserve constructs. Individuals with higher CR proxies (education, occupational attainment, IQ) can maintain better cognitive functioning despite brain atrophy, as seen in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Similarly, the predicted age difference (PAD)—the discrepancy between chronological age and MRI-estimated brain age—serves as a proxy for BR. Individuals with younger-appearing brains (negative PAD) show reduced risk of cognitive impairment in ALS, with higher cerebellar volume potentially driving this resilience [13].

Circuit-Level Mechanisms of Flexibility and Compensation

At the microcircuit level, flexibility is implemented through specific network architectures and dynamics. Research on attractor networks modeling WM and DM reveals how different circuit configurations balance stability and flexibility. The classic model features excitatory populations with self-excitation and mutual inhibition through a common pool of non-selective inhibitory neurons [17].

However, recent findings show that inhibitory neurons also form selective subnetworks, similar to excitatory populations. Circuits with this selective inhibition architecture develop during learning and create stronger resting states that improve DM accuracy. However, this comes at a cost: the resulting decision states are less stable, making WM more vulnerable to distractors. This creates a fundamental trade-off between accuracy and robustness that must be balanced according to task demands [17].

The mechanism of temporal gating provides a dynamic solution to this trade-off. A ramping non-selective input during the delay period of DM tasks can protect WM representations from distractors without substantially increasing thermodynamic costs. This temporal mechanism, combined with the selective-inhibition architecture, enables neural circuits to dynamically emphasize either robustness or flexibility based on specific cognitive demands [17].

Diagram 1: Temporal Gating Mechanism for Working Memory Robustness

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantifying Effective Model Complexity (EMC)

Objective: To empirically determine the largest sample size a neural network can perfectly fit using standard training procedures.

Materials:

- Computational environment (e.g., Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- Target dataset (e.g., CIFAR-10, ImageNet, or task-specific data)

- Model architecture(s) to evaluate

Procedure:

- Initialization: Begin with a small, randomly chosen subset of the training data (e.g., 10% of the proposed initial size).

- Training Phase: Train the model from a random initialization on the current data subset using standard optimization procedures until one of these convergence criteria is met:

- Gradient norms fall below a predefined threshold

- Training loss stabilizes

- Absence of negative eigenvalues in the loss Hessian (confirming a minimum)

- Evaluation: If training accuracy reaches 100%, proceed to the next iteration. If not, re-run training with three different random seeds to confirm consistent failure.

- Iteration: Independently sample a larger data subset and return to step 2.

- Termination: The EMC is the largest sample size for which perfect fitting is achieved across all random seeds.

Validation: Ensure that models reach true minima by verifying Hessian conditions, not merely low loss values, to prevent under-training from confounding capacity measurements [16].

Proteomic Profiling of Neuronal Differentiation

Objective: To systematically monitor changes in protein abundance throughout neuronal development stages.

Materials:

- Primary rat hippocampal neuron cultures

- Stable isotope labels for quantitative mass spectrometry

- Ultra-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to tandem mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS/MS)

- Strong cation-exchange (SCX) fractionation columns

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Harvesting: Grow primary hippocampal neurons in serum-free neurobasal medium. Harvest cells at days in vitro (DIV) 1, 5, and 14, corresponding to distinct developmental stages:

- DIV1: Axon formation and specification (stages 2-3)

- DIV5: Dendrite outgrowth (stage 4)

- DIV14: Synaptogenesis and maturation (stage 5)

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells, perform tryptic digestion, and label peptides with triplex stable-isotope dimethyl labels.

- Fractionation and Analysis: Separate peptides using SCX-based fractionation, followed by nano-UPLC coupled to high-resolution LC-MS/MS.

- Quantification and Bioinformatics:

- Calculate relative protein abundance from MS signal intensities of labeled peptides

- Perform fuzzy c-means clustering to identify protein expression profiles

- Conduct Gene Ontology enrichment analysis for functional annotation

- Validation: Select candidate proteins (e.g., NCAM1) for functional validation via knockdown/overexpression and morphological analysis.

This protocol successfully quantified 4,354 proteins across developmental stages, revealing that approximately one-third show significant expression changes during differentiation, providing a comprehensive resource for neurodevelopmental mechanisms [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Neural Implementation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CoCoDat Database | Organizes published biophysical, anatomical and electrophysiological data on single neurons and microcircuits | Constructing biophysically realistic models of cortical microcircuitry [19] |

| Stable Isotope Labeling | Enables quantitative proteomic analysis through mass spectrometry | Monitoring temporal protein expression dynamics during neuronal differentiation [18] |

| Attractor Network Models | Computational framework simulating neural population dynamics | Studying working memory and decision-making mechanisms [17] |

| brainageR Algorithm | Estimates brain age from structural MRI data | Calculating predicted age difference (PAD) as a proxy for brain reserve [13] |

| Primary Hippocampal Neurons | In vitro model of synchronized neuronal development | Profiling stage-specific molecular changes during neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis [18] |

Integrated Framework and Future Directions

The neural implementations of efficiency, capacity, and flexibility are not isolated properties but interacting dimensions of brain function that find their clinical relevance in the construct of cognitive reserve. Quantitative frameworks like EMC and landscape-flux theory provide powerful tools for mapping these properties across different scales, from protein networks to system-level cognition.

Future research should focus on integrating these multi-scale approaches, particularly bridging the gap between molecular mechanisms revealed by proteomic studies and computational models of network dynamics. The development of comprehensive databases like CoCoDat represents a crucial step in this direction, enabling the construction of biophysically realistic models constrained by experimental data [19]. Furthermore, translating these findings into clinical applications requires validating reserve proxies against direct measures of neural function and developing interventions that target the specific mechanisms underlying network efficiency, capacity, and flexibility.

Diagram 2: Multi-Scale Research Framework for Neural Implementation

Cognitive Reserve (CR) refers to the brain's ability to maintain cognitive performance in the face of age-related changes or pathological damage through adaptive functional and structural mechanisms [1]. This reserve encompasses both passive (brain reserve) and active (neural compensation) principles that allow individuals to withstand significant neuroanatomical decline while preserving cognitive function [20] [1]. The mechanistic background of CR has primarily focused on adaptive changes in neurons and neuronal networks, with distributed brain networks serving as the principal anatomical substrate for these protective processes. Key among these are the Default Mode Network (DMN), Frontoparietal Network (FPN), and specific temporal regions, which demonstrate remarkable flexibility and compensatory potential. Understanding how these networks interact to support CR provides critical insights for developing interventions to promote cognitive longevity and resilience against neurodegenerative conditions [20] [21] [1].

Core Neuroanatomical and Functional Definitions

Default Mode Network (DMN)

The DMN comprises a set of brain regions that show higher metabolic activity during rest than during externally-directed tasks [22]. This network is predominantly associated with self-referential thought, autobiographical memory, and social cognition [22]. Key hubs include the posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and angular gyrus. The DMN is particularly vulnerable to age-related decline and neurodegenerative processes, making its functional integrity a crucial biomarker for cognitive reserve [23] [22]. Recent evidence suggests the DMN dynamically interacts with executive and salience networks to support complex internal mentation, with different patterns of DMN connectivity associated with distinct profiles of spontaneous thought [22].

Frontoparietal Network (FPN)

The FPN, also referred to as the executive control network, supports flexible cognitive control, goal-directed behavior, and working memory [22]. This network includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal areas and demonstrates remarkable flexibility in coordinating distributed brain systems according to task demands [22]. The FPN plays a crucial role in compensatory mechanisms, often showing increased engagement in older adults with high cognitive performance despite structural decline [21]. This network's ability to dynamically reconfigure its connectivity patterns represents a central mechanism for maintaining cognitive function in aging.

Temporal Regions and Their Network Contributions

Temporal regions contribute significantly to multiple large-scale networks supporting CR. The medial temporal lobe, particularly the hippocampus, provides crucial interface between the DMN and memory systems, while temporal language areas (including Wernicke's area) form the core of the language network [21] [22]. These regions support semantic processing, mnemonic functions, and auditory integration [21]. In the context of CR, temporal regions demonstrate functional specialization and segregation that protects against age-related cognitive decline, with stronger left-temporal functional connectivity associated with preserved language capabilities in older adults [21].

Table 1: Core Brain Networks Supporting Cognitive Reserve

| Network | Key Regions | Primary Functions | Role in Cognitive Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Posterior cingulate cortex, Medial prefrontal cortex, Angular gyrus | Self-referential thought, Autobiographical memory, Social cognition | Vulnerability to aging; Hub for compensatory network integration [23] [22] |

| Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Posterior parietal cortex | Cognitive control, Goal-directed behavior, Working memory | Compensatory recruitment; Network reconfiguration [21] [22] |

| Temporal Regions | Medial temporal lobe, Superior/Middle temporal gyri | Semantic processing, Memory formation, Auditory integration | Functional segregation; Preservation of language and memory [21] [22] |

| Language Network (LAN) | Inferior temporal, Supramarginal, Frontal areas | Lexical access, Phonemic fluency, Semantic retrieval | Ipsilateral compensation; Maintained performance despite structural decline [21] |

| Salience Network (SAN) | Anterior cingulate, Anterior insula | Filtering salient stimuli, Integrating sensory-emotional information | Switching between DMN and FPN; Target for neuroprotective interventions [22] |

Methodological Approaches for Network Analysis in Cognitive Reserve

Static Functional Connectivity Analysis

Static functional connectivity (FC) methods identify functional properties of brain networks that remain stable over extended periods, typically using Fisher's r-to-z transformed Pearson's correlation coefficients computed across entire scanning sessions [23]. This approach has revealed remarkably consistent sets of large-scale functional brain networks that reflect communities of brain regions showing correlated activity, especially during resting state [23]. Static FC provides a baseline measure of network integrity and has demonstrated that stronger within-network connectivity and preserved between-network anti-correlations characterize individuals with higher cognitive reserve [20] [21].

Dynamic Functional Connectivity Approaches

Dynamic FC methods capture time-varying properties of functional brain networks, offering complementary insight into how the brain supports patterns of thinking [23]. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying CR as they capture moment-to-moment interactions between brain systems that give rise to psychological processes [23]. Key methods include:

- Sliding Window Analysis: The scan time-series is divided into epochs ("windows") typically 30-90 seconds long, with FC computed within each window [23]. Variability in connectivity is then quantified using standard deviation, variance, or sample entropy across windows [23].

- Dynamic Conditional Correlation (DCC): This approach avoids predefined windows by using time-series models to derive estimates of instantaneous connectivity, providing potentially higher temporal resolution [23].

- Leading Eigenvector Dynamics Analysis (LEiDA): Identifies framewise states using the Hilbert transform to compute the instantaneous phase of all brain regions, capturing recurring patterns of whole-brain phase synchrony [23].

- Co-activation Pattern (CAP) Analysis: Defines states from whole-brain patterns of activation for each volume, yielding transient network states reflecting recurring co-activation patterns [23].

- Hidden Markov Models (HMM): Identifies latent framewise states defined by activation and/or connectivity patterns, effectively capturing transient network states [23].

Structural Connectivity and Graph Theory Applications

Graph theory analyses of structural MRI data provide complementary measures of network organization supporting CR. By constructing networks from measures of cortical thickness, researchers can quantify network efficiency, transitivity, and modularity [21]. These analyses have revealed that more segregated cortical networks with strong involvement of frontal nodes allow older adults to maintain high cognitive performance despite structural decline [21]. Studies applying these methods have demonstrated that higher CR is associated with preserved network efficiency even in the face of gray matter atrophy [20] [21].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing brain networks in cognitive reserve research

Quantitative Findings in Cognitive Reserve Research

Research examining network dynamics in cognitive reserve has yielded consistent quantitative patterns across methodological approaches and populations. These findings demonstrate characteristic network signatures associated with preserved cognition despite aging or pathology.

Table 2: Dynamic Functional Connectivity Findings in Cognitive Reserve

| Network Property | Measurement Approach | Key Findings in High CR | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| FC Variability | Standard deviation of Fisher's z-transformed correlations across sliding windows [23] | Increased variability associated with better cognitive outcomes; reflects network flexibility [23] | Biomarker for compensatory capacity; Target for interventions [23] |

| Time-in-State | Proportion of scan time spent in specific transient network states [23] | Optimal balance between integrated and segregated states; Avoidance of rigid state persistence [23] [22] | Predictor of cognitive longevity; Altered in neuropsychiatric disorders [23] |

| State Persistence | Typical duration of transient network states [23] | Moderate persistence values; Neither too rigid nor too erratic [23] | Indicator of network stability; Excessive persistence in depression [23] |

| Transition Frequency | Tendency to transition between network states [23] | Higher transition rates associated with richer spontaneous thought profiles [22] | Correlate of cognitive flexibility; Reduced in neurodegenerative conditions [23] |

| Between-Network Desynchronization | Reduced FC between distinct functional networks [22] | Associated with complex, fluctuating thought patterns (88% of differences in fluctuating profile) [22] | Enables flexible network reconfguration; Supports diverse cognitive states [22] |

Table 3: Structural Network Correlates of Cognitive Reserve

| Network | Graph Theory Metric | Population Findings | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phonemic Fluency Network | Global efficiency, Transitivity [21] | Reduced efficiency and increased transitivity in high-performing older adults [21] | More segregated network organization supporting compensation [21] |

| Semantic Network | Nodal strength, Participation coefficient [21] | Greater participation of frontal nodes in high-performing older adults [21] | Frontal recruitment compensates for age-related decline [21] |

| Executive-Visuospatial Network | Within-network correlation strength [21] | Stronger correlations in high-performing older adults [21] | Contralateral compensation through right frontoparietal networks [21] |

| Default Mode Network | Gray matter integrity, Functional connectivity [20] | Lower gray matter but preserved functional connectivity in bilinguals [20] | CR mechanism maintains function despite structural decline [20] |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Neuroscience

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Research Function | Application in CR Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Atlases | GINNA Atlas [22] | Precisely defined functional networks with cognitive annotation | Identifying core functional networks with established psychological correlates [22] |

| Dynamic FC Algorithms | Sliding Window, DCC, LEiDA, CAP, HMM [23] | Quantifying time-varying properties of functional networks | Capturing moment-to-moment interactions between brain systems [23] |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Global efficiency, Transitivity, Nodal strength [21] | Quantifying organizational properties of structural and functional networks | Identifying network features associated with compensation [21] |

| Cognitive Phenotyping | ReSQ 2.0, Phonemic Fluency Tests [21] [22] | Characterizing spontaneous thought and cognitive performance | Linking network properties to specific cognitive profiles and abilities [21] [22] |

| Multimodal Integration | Voxel-based morphometry with resting-state FC [20] | Combining structural and functional measures in same participants | Disentangling compensation from aberrant network organization [20] [21] |

Integrated Framework: Network Dynamics Supporting Cognitive Reserve

The interplay between major brain networks creates a dynamic system that supports cognitive reserve through several integrated mechanisms. The DMN serves as a central hub, with its functional integrity and flexible coupling with other networks fundamentally supporting CR [23] [22]. The FPN provides compensatory control, dynamically reconfiguring its connectivity to maintain cognitive performance despite structural decline [21] [22]. Temporal regions contribute critical domain-specific processing, with functional segregation of language and memory networks preserving key cognitive abilities [21]. Together, these networks balance functional integration and segregation to support diverse cognitive states while maintaining specialized processing [22].

Diagram 2: Network interactions underlying cognitive reserve mechanisms

The study of key brain networks—particularly the DMN, FPN, and temporal regions—has fundamentally advanced our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive reserve. The dynamic interplay between these networks, characterized by a balance of functional integration and segregation, flexible reconfiguration, and compensatory recruitment, provides a robust neural foundation for maintaining cognitive performance despite age-related or pathological changes [23] [21] [22]. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs that track network dynamics alongside cognitive changes, develop network-based biomarkers for early identification of CR depletion, and explore interventions targeting network flexibility to enhance CR across the lifespan. Additionally, integrating neuroglial mechanisms into network models of CR will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how non-neuronal cells contribute to network resilience and adaptive capacity [1]. These advances will ultimately support the development of precision medicine approaches for maintaining cognitive health and mitigating neurodegenerative decline.

The constructs of brain reserve and cognitive reserve provide a compelling framework for understanding the marked individual differences in cognitive trajectories observed during aging and in the face of neuropathology. Historically conceptualized as static resources, contemporary research reveals these reserves to be dynamic entities, shaped by lifelong neuroplasticity. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on the neural mechanisms underpinning this plasticity, detailing how life experiences—from education and complex occupations to physical activity and cognitive training—continually remodel brain structure and function. We provide a technical overview of key experimental methodologies, quantitative data summaries, and essential research tools, framing the discussion within the broader context of developing interventions to enhance cognitive resilience and identifying novel targets for therapeutic drug development.

The concept of 'reserve' emerged from clinical observations of a disjunction between the degree of brain pathology and its clinical manifestations [5] [24]. Seminal post-mortem studies revealed individuals with significant Alzheimer's-type neuropathology who had exhibited minimal cognitive impairment ante-mortem [5] [24]. This paradox suggested the existence of a reserve that allows some brains to withstand more damage before showing clinical deficits.

The framework has since evolved into two complementary models, often analogized as the brain's 'hardware' and 'software' [5] [24]:

- Brain Reserve (BR): A passive, threshold model based on neuroanatomical capacity, such as brain size, neuronal count, and synaptic density. Individuals with greater initial brain capacity can tolerate more neurological attrition before crossing a threshold into impairment [5].

- Cognitive Reserve (CR): An active, functional model positing that individual differences in cognitive processes (e.g., network efficiency, capacity, flexibility) allow some people to better cope with brain changes or pathology by using pre-existing cognitive strategies or recruiting alternative brain networks [5].

Crucially, both BR and CR are not fixed but are now understood as products of lifelong plasticity [5] [25]. Life experiences, including educational attainment, occupational complexity, and engagement in leisure activities, continually shape the brain's structural and functional resources, thereby modifying an individual's reserve [5] [24] [26]. This dynamic nature positions reserve as a key target for interventions aimed at promoting cognitive health and resilience.

Neural Mechanisms of Plasticity Underpinning Reserve

The brain's ability to dynamically build and maintain reserve is rooted in fundamental mechanisms of neuroplasticity, which can be categorized as structural and functional.

Structural Neuroplasticity

Structural plasticity involves physical changes to neurons and neural networks, providing the anatomical substrate for reserve.

- Adult Neurogenesis: Contrary to long-held dogma, neurogenesis occurs in specific regions of the adult mammalian brain, most notably the subgranular zone of the hippocampal dentate gyrus [25]. The generation of new neurons contributes to the plasticity of hippocampal circuits, which are vital for learning and memory. This process is influenced by experience, such as physical activity and environmental enrichment [25].

- Dendritic Remodeling and Synaptogenesis: Learning and experience drive changes in dendritic spine density, size, and shape, as well as the formation of new synapses [25]. These modifications are fundamental to memory formation and are observed in conjunction with functional changes like long-term potentiation (LTP) [27].

- Activity-Dependent Myelination: Oligodendrocytes generate myelin sheaths that insulate axons, significantly increasing the speed and efficiency of neural communication. Crucially, myelination is not static but is influenced by neuronal activity, allowing experience to fine-tune brain connectivity and support the integrity of the brain-wide connectome [1].

Functional Neuroplasticity

Functional plasticity refers to the brain's ability to alter the strength and efficacy of synaptic transmission and reorganize its functional networks.

- Synaptic Plasticity: This includes persistent, experience-driven changes in synaptic strength, such as Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) and Long-Term Depression (LTD), which are considered primary cellular models for learning and memory [25] [27].

- Homeostatic Plasticity: Mechanisms such as synaptic scaling allow neurons to maintain stable firing rates over time by globally adjusting synaptic strength in response to changes in network activity. This process is crucial for keeping neural circuits within a functional dynamic range [27].

- Functional Reorganization: Following injury or during learning, the brain can reorganize itself. This includes phenomena like vicariation, where healthy brain regions take on new functions, and equipotentiality, where the opposite hemisphere can sustain functions lost to damage [28]. Advanced neuroimaging has demonstrated this reorganization in patients after stroke or hemispherectomy [28].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity Underpinning Reserve

| Plasticity Mechanism | Description | Primary Cell Types Involved | Contribution to Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Neurogenesis | Generation of new neurons in the adult hippocampus [25] | Neural Stem Cells (Radial Glia-like cells) [25] | Renewal of neuronal population for learning and memory circuits |

| Synaptogenesis & Spine Remodeling | Formation of new synapses and structural changes to dendritic spines [25] [27] | Neurons, Astrocytes [1] | Increases and refines connectivity, providing structural redundancy |

| Activity-Dependent Myelination | Myelination of axons modulated by neuronal activity [1] | Oligodendrocytes, Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells [1] | Optimizes network efficiency and timing of neural communication |

| Long-Term Potentiation/Depression (LTP/LTD) | Activity-dependent strengthening or weakening of synapses [25] [27] | Neurons | Basis for learning, memory, and adaptive cognitive strategies |

| Homeostatic Plasticity | System-wide adjustments to maintain network stability [27] | Neurons, Astrocytes [1] | Protects against hyper- or hypo-excitability, ensuring network health |

The Expanding Role of Neuroglia

The traditional, neuron-centric view of plasticity is being replaced by a more inclusive understanding that highlights the fundamental role of neuroglia in mediating and enabling reserve [1].

- Astrocytes are central to brain maintenance and homeostatic control. They regulate ions, clear neurotransmitters, supply neuronal metabolic substrates, and secrete factors that regulate synaptogenesis and synaptic pruning, thereby actively shaping neuronal circuits [1].

- Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, contribute to structural plasticity through synaptic pruning, refining neural connections by eliminating redundant or weak synapses [1].

- Oligodendrocytes support the brain's connectome through myelination. Their dysfunction is linked to white matter deterioration, a key factor in age-related cognitive decline [1].

Diagram 1: The plasticity-reserve model. Life experiences drive neuroplasticity, which enhances reserve through multiple structural and functional mechanisms.

Quantitative Evidence for Lifelong Plasticity

Empirical research provides robust quantitative data linking life experiences to measures of reserve and cognitive outcomes.

Proxies and Their Impact

Epidemiological and clinical studies often use proxies to measure reserve, demonstrating their quantitative impact on cognitive health.

Table 2: Proxy Measures of Cognitive Reserve and Their Documented Impact

| Reserve Proxy | Quantitative Association / Impact | Proposed Neural Correlates |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Higher prevalence of dementia in individuals with fewer years of education [24]. Each additional year of education is associated with reduced risk [5]. | Greater functional connectivity in frontoparietal networks; greater cortical thickness in temporal regions [24]. |

| Occupational Attainment | High occupational complexity is associated with reduced risk for Alzheimer's disease, independent of education [24]. | Increased local efficiency and functional connectivity in the medial temporal lobe [24]. |

| Lifestyle & Leisure Activities | A lifestyle characterized by engagement in intellectual and social activities is associated with a significantly reduced risk of dementia and slower cognitive decline [24] [26]. | At a given level of clinical impairment, higher leisure activity correlates with more advanced pathology, indicating greater resilience [24]. |

| Premorbid IQ | Higher premorbid IQ is associated with slower rates of cognitive decline in aging and dementia [5] [24]. | Specific patterns of brain activation that moderate the relationship between brain changes and performance [5]. |

Direct Experimental Evidence from Animal and Human Studies

Controlled studies provide direct evidence for the plasticity of reserve mechanisms.

Table 3: Key Experimental Findings on Plasticity and Reserve

| Experimental Paradigm | Key Finding | Implication for Reserve |

|---|---|---|

| Enriched Environment (Animal Models) | Exposure to complex environments with social interaction, physical activity, and novel objects enhances neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and improves learning and memory performance [25]. | Experience directly and positively modifies the brain's structural reserve and cognitive capacity. |

| Spatial Memory & Navigation (Cross-Species) | Aging animals and humans show spatial memory deficits, but with substantial individual variability. High-performing older individuals show more plastic and robust neural connections [5]. | Demonstrates individual differences in resilience and the role of maintained neural plasticity in successful cognitive aging. |

| Physical Exercise Interventions | Aerobic exercise triggers the release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a key protein for neuroplasticity, and increases cerebral blood flow [26]. | Exercise is a direct, non-pharmacological intervention that enhances the molecular and vascular substrates of plasticity. |

| Quantifying Neural Uncertainty (Mouse fS1) | In a vibration discrimination task, neural uncertainty in the primary somatosensory cortex decreased as learning progressed but increased when learning was interrupted [29]. | Provides a quantitative neural signature of the learning process, showing that plasticity dynamically reduces computational noise, thereby improving network efficiency. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Reserve and Plasticity

To advance the translational potential of reserve research, detailed methodologies are essential. Below is a protocol for a study that quantifies neural plasticity during learning, a core component of cognitive reserve.

Protocol: Quantifying Neural Uncertainty in the Mouse Somatosensory Cortex During Learning

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that used a deep learning approach to measure neural uncertainty as a marker of plasticity during learning [29].

Objective: To quantify how neural representations in the primary somatosensory cortex (fS1) stabilize (i.e., become less uncertain) as a mouse learns a sensory discrimination task.

Animals:

- Use 15 transgenic mice (e.g., Slc17a7;Ai93;CaMKIIa-tTA lines), aged 8-16 weeks, expressing GCaMP6f in excitatory neurons.

- House under a reversed 12-hour light/dark cycle and conduct experiments during the dark (active) phase.

- Exclusion Criterion: Mice with aberrant epileptiform activity.

Surgical Procedures (for Two-Photon Calcium Imaging):

- Anesthesia: Induce with an intraperitoneal injection of zoletil (3 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg).

- Headplate Implantation: Secure a custom titanium headplate over the right fS1 (coordinates: 0.25 mm anterior, 2.25 mm lateral from bregma) using dental cement.

- Craniotomy and Window: Perform a craniotomy and implant a layered glass cranial window (e.g., three coverslips bonded with UV-curable adhesive).

- Recovery: Allow at least one week for post-surgical recovery before behavioral training.

Behavioral Training & Data Acquisition:

- Habituation (3 days): Head-fix mice for increasing durations (10, 20, 40 min) with forepaws on platforms.

- Vibration Acclimation (3 days): Expose the left forepaw to 200 randomized vibration stimuli (frequencies 200-600 Hz) to prevent startle responses.

- Pretraining Imaging: Capture baseline GCaMP6f calcium activity in response to the same range of stimuli without any reward contingency.

- Water Restriction: Initiate controlled water access to motivate learning.

- Lick Shaping (3 days): Train mice to lick a port for water reward.

- Vibration Frequency Discrimination Task (8 days):

- Trial Structure: Each trial consists of: Pre-stimulus (1 s) -> Stimulus Delivery (0.25 s, 3 μm vibration) -> Delay (0.25 s) -> Response Window (1.5 s) -> Post-stimulus (1 s).

- Task Design:

- 'Go' Stimulus: 600 Hz vibration. A lick during the response window yields a water reward.

- 'No-Go' Stimulus: 200 Hz vibration. Withholding a lick is correct.

- 'Probe' Stimuli: Vibrations at 40-Hz intervals between 200-600 Hz to generate psychometric curves.

- Perform Two-Photon Calcium Imaging throughout all trials to record neural activity from hundreds of neurons in fS1 simultaneously.

Data Analysis:

- Neural Decoding and Uncertainty Quantification:

- Use a Neuron Transformer Model with Monte Carlo Dropout (MCD).

- Train the model to decode stimulus features or decision variables from the neural population activity.

- During inference, run the model multiple times with dropout active. The variance in the model's output across runs serves as the quantitative measure of neural uncertainty [29].

- Correlation with Behavior:

- Correlate the trial-by-trial neural uncertainty with task performance (correct vs. incorrect decisions) and learning stage (early vs. late).

- Expected Result: Uncertainty decreases as learning progresses and is higher on incorrect trials [29].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for quantifying neural plasticity during learning in mice.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plasticity and Reserve Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GCaMP6f (Genetically Encoded Ca²⁺ Indicator) | Reports neural activity in the form of fluorescence changes in response to intracellular calcium transients [29]. | Real-time imaging of population neural activity in behaving mice during learning tasks [29]. |