Neuroplasticity in Behavioral Adaptation and Optimal Performance: Mechanisms, Applications, and Therapeutic Frontiers

This article synthesizes current research on neuroplasticity to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding its role in behavioral adaptation and the pursuit of optimal performance.

Neuroplasticity in Behavioral Adaptation and Optimal Performance: Mechanisms, Applications, and Therapeutic Frontiers

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on neuroplasticity to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding its role in behavioral adaptation and the pursuit of optimal performance. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational mechanisms, from synaptic remodeling and neurogenesis to large-scale network reorganization. It critically evaluates innovative methodologies—including neuromodulation, cognitive remediation, and biomarker-guided interventions—for harnessing plasticity. The review also addresses significant challenges such as maladaptive plasticity and recovery plateaus, while presenting validation strategies through advanced neuroimaging and case studies. Finally, it discusses the translational implications of these findings for developing next-generation therapeutic interventions and precision medicine approaches in neurology and psychiatry.

The Core Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity: From Synapses to Systems

Neuroplasticity is fundamentally defined as the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections [1]. This dynamic capacity, which persists throughout the lifespan, allows the brain to adapt following injuries, learn new skills, consolidate memories, and adjust to environmental changes [2]. The concept of a plastic brain stands in stark contrast to the early, rigid view of the brain as a static organ. Research has now firmly established that the brain exhibits a remarkable capacity for functional and structural change, a property central to behavioral adaptation and the pursuit of optimal performance [3]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the core mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and key research tools in neuroplasticity research, framed within the context of behavioral adaptation and optimal performance.

Core Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity manifests through two primary, interconnected biological mechanisms: structural plasticity, which involves physical changes to neuronal connections and brain anatomy, and functional plasticity, which involves changes in the efficiency and strength of synaptic communication and network dynamics [2] [1].

Structural Neuroplasticity

Structural plasticity refers to the brain's ability to change its physical architecture. This includes:

- Synaptic Plasticity: The experience-dependent long-lasting change in the strength of neuronal connections, most famously exemplified by long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP, first discovered by Bliss and Lomo in 1973, describes the persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity, forming a fundamental cellular model for learning and memory [1].

- Morphological Changes: Alterations in neuronal morphology, such as increased dendritic spines, modified dendritic branching, and the formation of new synapses [3].

- Adult Neurogenesis: The generation of new neurons in the adult brain. While conclusively demonstrated in the hippocampus and olfactory bulb of small mammals, its extent and functional significance in humans remain an active area of investigation and debate [2] [1].

Functional Reorganization

Functional plasticity involves the reassignment of neural resources to support adaptation, particularly after injury. Key concepts include:

- Vicariation and Equipotentiality: Vicariation occurs when a brain region takes on a new, unrelated function, while equipotentiality suggests that if damage occurs early in life, other brain areas have the potential to assume lost functions. Modern neuroimaging shows the brain employs a combination of both, with the remaining hemisphere reorganizing to restore function after procedures like hemispherectomy [1].

- Diaschisis: A concept where damage to one part of the brain causes a loss of function in a distant, but connected, area due to the loss of excitatory input. This can be observed as hypoperfusion in the ipsilateral thalamus following a middle cerebral artery stroke [1].

- Map Expansion: The phenomenon where the cortical representation of a frequently used body part expands at the expense of less-used areas, demonstrating the experience-dependent nature of functional organization [2].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Functional Reorganization After Brain Injury

| Concept | Definition | Clinical/Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Vicariation | A brain region overtakes a new function that it was not originally responsible for. | Reorganization of the supplemental motor area to control motor function after a primary motor cortex stroke [1]. |

| Equipotentiality | The capacity of certain brain areas, particularly in the young brain, to assume the functions of a damaged region. | Functional recovery after unilateral brain injury in childhood, where the remaining hemisphere supports development [1]. |

| Diaschisis | Loss of function in a brain region remote from, but connected to, the site of primary damage. | Hypoperfusion of the ipsilateral thalamus observed after an acute middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke [1]. |

Quantitative Frameworks and Research Data

A key application of neuroplasticity research involves developing interventions to enhance brain performance and resilience. Physical exercise serves as a powerful, non-pharmacological modulator of brain plasticity, with its effects quantifiable across different exercise modalities.

Table 2: Neuroplasticity Outcomes Modulated by Physical Exercise Parameters

| Exercise Modality | Intensity | Duration | Key Neuroplastic Effects on Brain Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Light-to-Moderate (57-76% HRmax) | Long-Term (≥1 year) | Increased functional connectivity in the Default Mode and Salience Networks [4]. |

| Strength | Vigorous (70-<85% 1RM) | Short-Term (<1 year) | Functional changes in the Central Executive and Visuospatial Networks [4]. |

| Mixed Exercise | Light-to-Moderate | Long-Term (≥1 year) | Structural and functional changes in the Sensorimotor Network [4]. |

The timeline of neuroplastic changes following neural injury occurs in distinct, overlapping phases, which can be quantified and targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Table 3: Temporal Phases of Neuroplasticity After Injury

| Phase | Timeline | Primary Neuroplastic Events |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | First 48 hours | Initial cell death and loss of cortical pathways; recruitment of secondary neuronal networks to maintain function [1]. |

| Subacute | Following weeks | Shift in cortical pathways from inhibitory to excitatory; synaptic plasticity and formation of new connections [1]. |

| Chronic | Weeks to months | Axonal sprouting and further structural reorganization of brain networks around the site of damage [1]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Investigating Experience-Dependent Plasticity Using an Enriched Environment Paradigm

This protocol is used to study how complex sensory, cognitive, and motor stimulation drive structural and functional plasticity in animal models, relevant to research on optimal performance and cognitive reserve [3].

- Subject Housing: Randomly assign subjects (e.g., rodent models) to either an Enriched Environment (EE) or a Standard Environment (SE) control group.

- Environmental Design:

- EE Condition: A large cage containing a variety of changing stimuli such as running wheels, tunnels, ladders, and novel objects of different textures and shapes. Social housing is standard.

- SE Condition: A standard laboratory cage with standard bedding, food, and water but no additional complex stimuli.

- Intervention Duration: The intervention typically lasts for several weeks to months, with objects in the EE being rearranged and replaced regularly to maintain novelty.

- Tissue Preparation and Analysis:

- Perfuse and fix the brains transcardially.

- Section brain regions of interest (e.g., hippocampus, cerebral cortex).

- Employ staining techniques such as Golgi-Cox impregnation to visualize and quantify dendritic branching and spine density.

- Use immunohistochemistry for markers like c-Fos to map neuronal activity or BrdU/DCX to assess adult neurogenesis.

- Behavioral Correlates: Conduct behavioral tests (e.g., Morris water maze, novel object recognition) at the end of the environmental exposure period to correlate neuroplastic changes with cognitive performance.

Protocol: Functional MRI (fMRI) in Studying Neuroplasticity in Post-Stroke Aphasia

This protocol assesses functional reorganization of language networks in the human brain after injury, a key area for understanding vicariation and diaschisis [5].

- Participant Selection: Recruit a cohort of individuals with post-stroke aphasia and age-matched neurologically normal controls.

- Task Design: Develop a block-design or event-related fMRI paradigm. Tasks should engage core language processes (e.g., auditory comprehension, semantic decision, verbal fluency) and include a low-level control task (e.g., tone discrimination, rest) for contrast.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images and T2*-weighted BOLD fMRI images on a 3T MRI scanner.

- Preprocessing: Preprocess data using standard pipelines (e.g., SPM, FSL) including realignment, slice-time correction, normalization to standard space (e.g., MNI), and smoothing.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Model the BOLD response for each condition at the single-subject level.

- Perform second-level group analyses to identify:

- Between-Group Differences: Regions showing significantly different activation in patients vs. controls.

- Correlation with Behavior: Regions where activation magnitude correlates with language performance scores in the aphasia group.

- Critical Methodological Considerations:

- Control for Task Performance: Match task difficulty or use performance as a covariate to avoid confounds from differing effort or ability [5].

- Contrast Validity: Ensure the task contrast effectively isolates language-specific activation in control subjects [5].

- Multiple Comparisons Correction: Apply appropriate family-wise error (FWE) or false discovery rate (FDR) correction to statistical maps [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Cutting-edge research in neuroplasticity relies on a suite of sophisticated tools and reagents to probe the molecular, cellular, and systems-level mechanisms of brain adaptation.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Reagents in Neuroplasticity Research

| Research Tool/Reagent | Primary Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Bruker timsTOF Ultra 2 Mass Spectrometer | A state-of-the-art instrument for single-cell proteomic and lipidomic analysis, enabling the precise quantification of proteins and lipids within individual neurons to study aging and cognitive decline [6]. |

| Patch-seq | An integrated technique that combines patch-clamp electrophysiology (to record neuronal electrical activity), immunohistochemistry (to locate proteins), and single-cell RNA sequencing (to profile gene expression) to comprehensively characterize individual neurons [6]. |

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | Antibodies that target phosphorylated epitopes on proteins (e.g., NMDA receptor subunits, CREB) to study activity-dependent signaling cascades and synaptic plasticity mechanisms like LTP [2]. |

| Neuromodulators (Dopamine Agonists/Antagonists) | Pharmacological agents used to manipulate dopaminergic and other neuromodulatory systems, which are known to positively influence synaptic plasticity and learning [1]. |

| Activity-Dependent Biomarkers (c-Fos, Arc) | Endogenous proteins whose expression is rapidly upregulated in neurons following activation. Their detection via immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization allows for functional mapping of neural circuits engaged by specific experiences or behaviors [3]. |

| BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine) | A thymidine analog that incorporates into the DNA of dividing cells. It is used in conjunction with cell-specific markers (e.g., NeuN, DCX) to label and track the birth, migration, and fate of new neurons in the process of adult neurogenesis [3]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

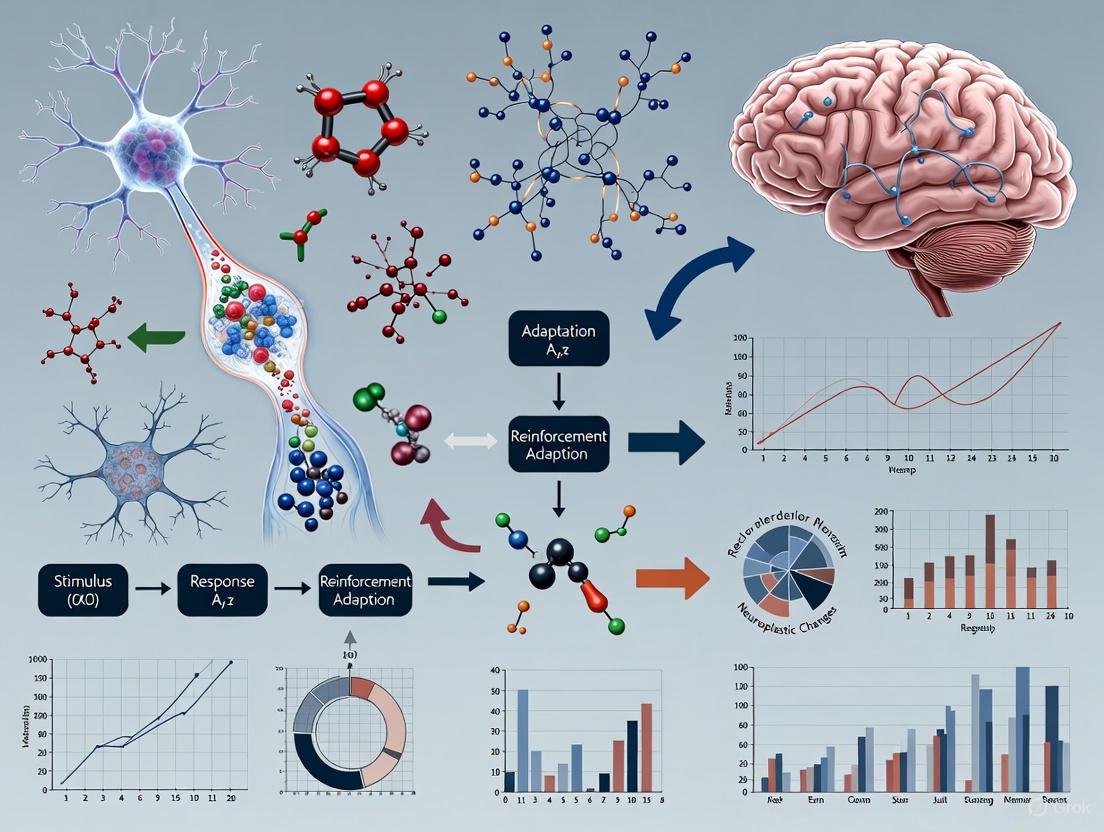

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate core concepts and experimental workflows in neuroplasticity research. The color palette and contrast ratios adhere to the specified technical requirements.

Hebbian Synaptic Plasticity Pathway

Functional Reorganization Post-Stroke

Single-Cell Plasticity Analysis Workflow

Neuroplasticity, the biological capacity of the brain to reorganize its neural connections in response to environmental stimuli, experience, learning, and injury, serves as the fundamental substrate for behavioral adaptation and optimal performance [7]. This adaptive capability encompasses a range of cellular and molecular mechanisms, including changes in synaptic strength and connectivity, the formation of new synapses, alterations in the structure and function of neurons, and the generation of new neurons [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core mechanisms—synaptic plasticity, dendritic remodeling, and neurogenesis—is paramount for developing interventions that enhance brain function and promote resilience across the lifespan. This technical guide synthesizes current research on these foundational processes, framing them within the broader thesis of neuroplasticity's role in enabling organisms to achieve optimal performance in dynamic environments, a concept explored in adaptive neurobiological plasticity research [3] [8].

Synaptic Plasticity: Mechanisms of Information Storage

Synaptic plasticity refers to the activity-dependent modification of the strength and efficacy of synaptic transmission. This dynamic process is widely regarded as the primary cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory [9] [7].

Key Molecular Mechanisms

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) and Long-Term Depression (LTD) represent the most extensively studied forms of functional synaptic plasticity. LTP is a persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity, whereas LTD is a persistent weakening of synapses [7]. The induction of these processes often involves NMDA receptor activation, leading to calcium influx that triggers divergent intracellular signaling cascades [9]. Expression mechanisms include:

- AMPA receptor trafficking: LTP often involves the insertion of additional AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic density, while LTD involves their internalization [9].

- Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles: Key enzymes include Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), which promotes AMPA receptor insertion during LTP, and protein phosphatases that facilitate AMPA receptor removal during LTD [9].

- Structural modifications: Changes in synapse size and shape often accompany long-lasting plasticity [10].

Table 1: Quantitative Profiles of Dendritic Spine Subtypes Observed In Vivo

| Spine Subtype | Relative Stability | Morphological Characteristics | Functional Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filopodia | Highly dynamic (appear/disappear in ~10 min) [10] | Long, thin protrusions without bulbous heads [10] | Predominant in early postnatal life; exploratory function [10] |

| Thin Spines | Moderately dynamic (can persist days) [10] | Small heads with long, thin necks [10] | Potential transitional state; can form functional synapses [10] |

| Mushroom Spines | Highly stable (can persist months to years) [10] | Large heads with variably lengthed necks [10] | Considered "memory spines" with stable synaptic connections [10] |

| Stubby Spines | Moderately stable | Originally described as lacking necks; STED microscopy reveals very short necks [10] | May represent active mushroom spines with shortened necks [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Synaptic Plasticity Research

In Vivo Two-Photon Microscopy for Spine Imaging:

- Animal Preparation: Utilize transgenic mice (e.g., Thy1-GFP) or deliver fluorophores via viral transmission, in utero electroporation, or single-cell electroporation for controlled neuronal labeling [10].

- Cranial Window Surgery: Either perform a craniotomy followed by implantation of a transparent window or use a less invasive thinned-skull technique where the skull is carefully shaved to approximately 20μm thickness [10].

- Image Acquisition: Image the same dendritic segments repeatedly over days to months using two-photon microscopy [10].

- Data Analysis: Quantify spine density, morphology, formation, and elimination rates across experimental conditions [10].

Electrophysiological Assessment of LTP/LTD:

- Slice Preparation: Prepare acute hippocampal or cortical brain slices (300-400μm thick) from rodents.

- Stimulation and Recording: Place a stimulating electrode in afferent pathways and a recording electrode in the postsynaptic region.

- Baseline Recording: Measure field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) for at least 20 minutes to establish stable baseline transmission.

- Induction Protocol: Apply high-frequency stimulation (e.g., 100Hz tetanus) for LTP or low-frequency stimulation (e.g., 1Hz for 15 minutes) for LTD.

- Monitoring: Record fEPSPs for at least 60 minutes post-induction to quantify the magnitude and persistence of plasticity [9].

Dendritic Remodeling: Structural Adaptation of Neural Circuits

Dendritic spines are small protrusions studding neuronal dendrites that constitute the postsynaptic sites of most excitatory synapses in the mammalian brain [10]. Their structural plasticity represents a critical interface between experience and neural circuit modification.

Spine Dynamics and Behavioral Adaptation

Dendritic spines are highly dynamic structures whose turnover and stabilization are modulated by neuronal activity, experience, and developmental age [10]. In vivo imaging studies reveal that spine dynamics follow specific patterns across development and different cortical regions:

Table 2: In Vivo Spine Stability Across Development and Brain Regions

| Brain Region | Animal Age | Stability Measurement | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Cortex, Layer 5 | P30 | 73% stable over 30 days | Spines become more stable from juvenile to adult ages | [10] |

| Visual Cortex, Layer 5 | 4 months | 96% stable over 30 days | Significant stabilization in adulthood | [10] |

| Somatosensory Cortex, Layer 5 | P16-25 | 35% stable over ≥8 days | Developmental increase in stability | [10] |

| Somatosensory Cortex, Layer 5 | P175-225 | 73% stable over ≥8 days | Progressive stabilization through adolescence | [10] |

| Barrel Cortex, Layer 5 | P30 | 60% stable over 22 months | Subset of spines can last throughout life | [10] |

| Barrel Cortex, Layer 5 | 4-6 months | 74% stable over 18 months | Increased stability in adulthood | [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Dendritic Spine Analysis

Long-Term In Vivo Spine Imaging Protocol:

- Animal Model Selection: Use Thy1-GFP-M or similar transgenic mice expressing fluorescent proteins in sparse neuronal populations [10].

- Surgical Preparation: Implement either thinned-skull or cranial window approach based on experimental needs. Thinned-skull is less invasive but requires re-thinning for long-term studies; cranial windows allow longer imaging durations but may cause initial inflammation [10].

- Baseline Imaging: Collect high-resolution z-stacks of labeled dendritic segments using two-photon microscopy.

- Experimental Manipulation: After baseline imaging, introduce experimental variables such as sensory deprivation, motor learning tasks, or pharmacological treatments [10].

- Longitudinal Imaging: Re-image the exact same dendritic segments at multiple time points (hours to months apart) using vascular landmarks and branch patterns for relocation.

- Morphological Classification: Categorize spines based on established morphological criteria (filopodia, thin, stubby, mushroom) and track their fate over time [10].

Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM):

- Perform in vivo two-photon imaging of spines as described above.

- Transcardially perfuse animal with fixative following final imaging session.

- Process brain tissue for EM analysis using standard protocols.

- Relocate the previously imaged dendritic segments using distinctive landmarks.

- Correlate spine dynamics observed in vivo with ultrastructural features such as postsynaptic density size, presynaptic bouton characteristics, and mitochondrial content [10].

Neurogenesis: Adding New Neurons to Existing Circuits

Neurogenesis refers to the process of generating new functional neurons from neural precursor cells. While most prolific during development, this process continues in specific regions of the adult brain, contributing to neural plasticity throughout the lifespan [7].

Developmental and Adult Neurogenesis

Developmental Neurogenesis occurs primarily during embryonic and early postnatal stages, involving the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of neural precursor cells from the ventricular zone [7]. Key stages include:

- Neural tube formation around embryonic day 30 in humans

- Interkinetic nuclear migration of neural stem cells between weeks 4-5 of human gestation

- Neurogenesis onset around gestational week 5 with asymmetric division of radial glial cells

- Synaptogenesis beginning approximately at human gestational week 27, continuing postnatally with a peak synapse density around age two followed by synaptic pruning [7]

Adult Neurogenesis persists in two main neurogenic niches: the subventricular zone (SVZ) lining the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus [7]. The process involves highly regulated stages of cell proliferation, neuronal fate specification, migration, maturation, and functional integration into existing circuits [7].

Experimental Protocols for Neurogenesis Research

Labeling and Tracking Adult-Born Neurons:

- Thymidine Analog Administration: Inject animals with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) or other thymidine analogs to label dividing cells.

- Perfusion and Tissue Collection: Sacrifice animals at multiple time points post-injection (hours for proliferation, days for fate specification, weeks for maturation and integration).

- Immunohistochemical Processing: Use antibodies against BrdU combined with cell-type-specific markers (e.g., NeuN for mature neurons, GFAP for astrocytes, DCX for immature neurons).

- Quantification: Employ stereological counting methods (e.g., optical fractionator) to obtain unbiased estimates of cell numbers in neurogenic regions.

Functional Manipulation of Neurogenesis:

- Genetic Ablation Models: Use transgenic approaches (e.g., thymidine kinase models) to specifically ablate dividing neural precursor cells.

- Optogenetic/Chemogenetic Manipulation: Express light-sensitive or designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drug (DREADD) proteins in adult-born neurons to selectively activate or inhibit their activity.

- Behavioral Assessment: Evaluate cognitive functions (particularly hippocampus-dependent tasks such as pattern separation) following manipulation of adult neurogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neuroplasticity Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thy1-GFP Transgenic Mice | Sparse neuronal labeling for in vivo imaging | Enables longitudinal tracking of dendritic spines in specific neuronal populations [10] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | High-resolution live imaging in intact brain | Allows repeated imaging of the same neuronal structures over time with minimal phototoxicity [10] |

| BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine) | Thymidine analog for labeling dividing cells | Used to birth-date newborn cells and track their fate in neurogenesis studies [7] |

| Cell-Type-Specific Markers | Identification of neural cell types | Sox2, Nestin (neural stem cells); DCX, βIII-tubulin (immature neurons); NeuN (mature neurons) [7] |

| Viral Vector Systems | Targeted gene delivery | AAVs, lentiviruses for gene overexpression, knockdown, or expression of fluorescent reporters [10] |

| Electrophysiology Setup | Functional assessment of synaptic transmission | Extracellular field recordings for LTP/LTD; patch-clamp for detailed biophysical analysis [9] |

| STED Microscopy | Superresolution imaging | Reveals spine ultrastructural details (e.g., short necks of stubby spines) beyond diffraction limit [10] |

The cellular and molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity, dendritic remodeling, and neurogenesis represent complementary adaptive strategies the brain employs to optimize performance in dynamic environments. Synaptic plasticity provides the mechanism for rapid information storage, dendritic remodeling enables structural circuit adaptation, and neurogenesis introduces new computational elements into existing networks. Research in adaptive neurobiological plasticity suggests that interventions such as environmental enrichment, which enhances behavioral affordances, can harness these mechanisms to promote cognitive reserve and resilience [3]. For drug development professionals, understanding these foundational processes and their methodological assessment provides critical insights for developing targeted therapies that enhance neuroplasticity to maintain optimal brain function across the lifespan and in neurological disorders.

The central nervous system's (CNS) limited regenerative capacity presents a significant challenge in treating neurodegenerative diseases, traumatic injuries, and stroke-related damage. Within this context, neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to reorganize its structure and function—provides the fundamental framework for behavioral adaptation and functional recovery. The efficacy of this plastic response is not solely governed by neurons but is critically orchestrated by a suite of non-neuronal cells that create permissive microenvironments for repair. Glial cells, once considered merely supportive "neural glue," are now recognized as active participants in neural circuit formation, plasticity, and regeneration [11] [12]. Similarly, neural stem cells (NSCs) and oligodendrocytes play indispensable roles in replenishing cellular components and restoring efficient neural communication. Understanding the precise mechanisms by which these cellular players contribute to neural repair is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that optimize the brain's innate capacity for self-renewal and functional adaptation, ultimately enhancing behavioral outcomes and cognitive performance following neurological insult.

This technical review synthesizes contemporary research on the roles of glial cells, neural stem cells, and oligodendrocytes in neural repair mechanisms, framing their functions within the broader context of neuroplasticity-driven recovery. We provide detailed experimental methodologies, quantitative analyses of cellular responses, and visualization of key signaling pathways to serve as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the frontier of regenerative neurology.

Glial Cells: Master Regulators of the Neural Milieu

Astrocytes: Dual Roles in Synaptic Homeostasis and Scar Formation

Astrocytes, a predominant glial cell type, exhibit functional duality in neural repair processes. They are integral to synaptic homeostasis, regulating extracellular neurotransmitter levels, particularly glutamate, via excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) to prevent excitotoxicity [13]. Furthermore, astrocytes release gliotransmitters such as ATP and D-serine, which are essential for synaptic plasticity and memory encoding [13]. Following injury, however, astrocytes undergo reactive astrogliosis, forming glial scars that initially seal the lesion site but subsequently release chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) that inhibit axonal regeneration [11].

Table 1: Astrocyte Functions and Associated Molecular Markers in Neural Repair

| Function | Mechanism | Key Molecular Players | Impact on Repair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Homeostasis | Glutamate uptake, gliotransmitter release | EAATs, D-serine, ATP [13] | Prevents excitotoxicity, supports plasticity |

| Metabolic Support | Lactate shuttle via Aquapor-4 (AQP4) channels | AQP4, MCT1 [11] [13] | Provides energy substrate for neurons |

| Edema Regulation | Cellular volume regulation at blood-brain barrier | TRPV4 channels, AQP4 [11] | Modulates severity of cerebral edema during ischemia |

| Scar Formation | Reactive gliosis, CSPG secretion | GFAP, CSPGs [11] | Barriers lesion site but inhibits regeneration |

Microglia: Immune Surveillance and Synaptic Remodeling

As the resident immune cells of the CNS, microglia are pivotal in responding to injury by clearing cellular debris and modulating neuroinflammation [11]. They exhibit remarkable plasticity, transitioning between pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory, regenerative (M2) phenotypes. Beyond their immune functions, microglia contribute to activity-dependent synaptic pruning, a process crucial for circuit refinement during learning and recovery [13]. Dysregulation of this pruning function is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases; for instance, excessive synaptic elimination by microglia can contribute to memory loss in Alzheimer's disease pathology [13].

Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses have revealed significant heterogeneity within microglial populations, with distinct subtypes emerging in different pathological contexts [11]. This functional diversity presents both a challenge and an opportunity for therapeutic intervention, as selectively modulating specific microglial subpopulations could promote beneficial phagocytic activity while curbing detrimental inflammatory responses.

Neural Stem Cells: Engines of Regeneration and Paracrine Signaling

Neural stem cells (NSCs), residing in niches such as the subventricular zone (SVZ) and subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus, hold immense therapeutic potential due to their ability to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [14]. The regenerative capacity of endogenous NSCs is often insufficient for complete functional restoration, particularly in the inhibitory microenvironment of the injured and aging brain [14]. Consequently, therapeutic strategies have evolved to include NSC transplantation. A 2025 study demonstrated that transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells (hiPSC-NPCs) survived for over five weeks in stroke-injured mouse brains, primarily differentiating into GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons and promoting functional recovery [15].

The mechanism of action for NSC therapies is increasingly attributed to potent paracrine effects rather than direct cell replacement alone. NSCs secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing bioactive molecules—including miRNAs, proteins, and lipids—that modulate neuroinflammation, promote neurogenesis, and restore cellular bioenergetics [14]. These EVs represent a promising cell-free therapeutic modality, circumventing challenges associated with direct cell transplantation, such as tumorigenesis and immune rejection.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing NSC Graft-Host Integration

The following methodology outlines the key procedures for evaluating the survival, integration, and therapeutic efficacy of transplanted NSCs, as utilized in recent groundbreaking research [15].

- 1. Cell Preparation: Differentiate human iPSCs into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) under xeno-free, GMP-compliant conditions. Characterize NPCs via immunocytochemistry for canonical markers (Nestin, Pax6) and confirm the absence of pluripotency markers (Nanog).

- 2. Animal Model & Surgery: Subject mice to photothrombotic stroke induction in the sensorimotor cortex. Confirm stroke success by Laser-Doppler Imaging (LDI), expecting a 60-70% reduction in cerebral blood flow.

- 3. Cell Transplantation: At 7 days post-injury (dpi), stereotactically inject NPCs expressing a dual-reporter (rFluc-eGFP) into the peri-infarct region. Control groups receive a vehicle injection.

- 4. Graft Monitoring: Track cell survival longitudinally over 35 days using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Quantify signal intensity to monitor graft viability and expansion.

- 5. Histological Analysis: At endpoint (e.g., 43 dpi), perform immunohistochemistry on brain sections using antibodies against Human Nuclei (HuNu) to demarcate graft location and size. Additional staining for neuronal (βIII-Tubulin) and astrocytic (S100β, GFAP) markers assesses differentiation.

- 6. Functional Assessment: Evaluate motor recovery using deep learning-based gait analysis and fine-motor tests. Compare performance between NPC-treated and vehicle-treated groups over time.

- 7. Molecular Profiling: Conduct single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) on grafted cells and surrounding host tissue to characterize neuronal subtypes formed and analyze graft-host crosstalk signaling pathways.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating neural stem cell therapy in a stroke model.

Oligodendrocytes: Restoring Conduction and Metabolic Support

Oligodendrocytes (OLs) are the myelinating cells of the CNS, essential for saltatory conduction and axonal integrity. A single oligodendrocyte can myelinate up to 50 axonal segments, significantly enhancing the speed and efficiency of action potential propagation [12]. Following demyelinating injuries or diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), OLs facilitate repair through remyelination, a process driven by the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) resident in the adult CNS [12].

Beyond insulation, OLs provide critical metabolic support to axons. They uptake glucose via monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and convert it to lactate, which is shuttled to axons to meet their high energy demands [12]. Disruption of this metabolic coupling, as evidenced by MCT1 knockout models, leads to axonal degeneration and motor deficits, underscoring its necessity for long-term axonal survival [12]. Furthermore, OLs contribute to neural plasticity; learning and motor skill acquisition stimulate OPC differentiation and adaptive changes in myelin, a process termed "myelin plasticity" [12] [13].

Table 2: Oligodendrocyte Lineage Functions in Homeostasis and Repair

| Cell Type | Primary Function | Key Markers | Role in Repair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell (OPC) | Proliferation, migration, surveillance | NG2, PDGFRα [11] | Recruited to site of injury, source of new OLs |

| Mature Oligodendrocyte | Myelination, metabolic support | MBP, PLP, MCT1 [12] | Forms new myelin sheaths (remyelination), supports axonal health |

| Myelin Sheath | Axonal insulation, saltatory conduction | Lipids (70%), MBP, PLP [12] | Restores conduction velocity, protects axon |

Signaling Pathways Mediating Cellular Crosstalk in Repair

The functional recovery of the nervous system is not the result of isolated cellular actions but is driven by intricate molecular crosstalk between grafted NSCs, endogenous glia, and host neurons. snRNA-seq data from a 2025 transplantation study revealed that graft-derived GABAergic neurons engage with host tissue through several key signaling pathways: Neurexin (NRXN), Neuregulin (NRG), Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM), and SLIT pathways [15]. These interactions are hypothesized to underpin observed therapeutic effects, such as reduced inflammation, enhanced angiogenesis, and structural repair.

Concurrently, astrocytic signaling involving channels like Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) and Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) plays a critical role in cellular volume regulation, influencing the onset and severity of cerebral edema during ischemic events [11]. Research using knockout models has demonstrated that the deletion of these channels alters the expression of glutamate receptors and other ion channels, impacting the brain's response to injury beyond direct volume control [11].

Diagram 2: Molecular graft-host crosstalk via key signaling pathways driving neural repair.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Repair Studies

| Reagent / Model | Category | Specific Example / Target | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| hiPSC-derived NPCs | Cell Source | Xeno-free, GMP-compliant differentiation [15] | Cell therapy, graft-host interaction studies |

| Reporter Constructs | Tracking | rFluc-eGFP dual reporter [15] | Longitudinal monitoring of graft survival and migration |

| snRNA-seq | Profiling | 10x Genomics Platform | Unbiased characterization of graft/host cell types and pathways |

| Photothrombotic Stroke Model | Animal Model | Focal ischemia in sensorimotor cortex [15] | Preclinical testing of repair therapies |

| Optogenetics | Modulation | Channelrhodopsin (Opsins) in glia [11] | Precise control of glial cell activity to study function |

| Senolytic Compounds | Therapeutics | Senescence-targeting drugs [11] | Clear senescent cells to improve cognition post-injury |

| Clemastine | Remyelination Drug | M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist [13] | Promote OPC differentiation and remyelination |

| Anti-GFAP / Iba1 / HuNu | Antibodies | Cell-specific markers [11] [15] | Histological identification of astrocytes, microglia, and human grafts |

The intricate interplay between glial cells, neural stem cells, and oligodendrocytes forms the bedrock of the CNS's reparative response, directly influencing the neuroplasticity that underlies behavioral adaptation and functional recovery. Astrocytes and microglia perform complex, dual roles that can either support or hinder repair, while oligodendrocytes extend their function beyond mere insulation to include vital metabolic and plastic support. The emergence of NSC-derived therapies, particularly those leveraging paracrine effects via extracellular vesicles, represents a paradigm shift in regenerative strategies.

Future research must prioritize resolving the contextual signals that determine whether glial responses are beneficial or detrimental. Advancing the clinical translation of these cellular players will require refinements in targeted delivery, such as optimized nanoparticles for glial modulation [11], and safety-enhanced cell grafts. By deepening our understanding of these key cellular players and their complex interactions, we can pioneer novel, effective treatments that harness the brain's innate plastic potential to restore function after neurological injury and disease.

Neuroplasticity, the brain's remarkable capacity to change its structure and function in response to experience, represents a fundamental property of the nervous system that enables adaptation, learning, and memory formation [16]. This dynamic process operates along a spectrum of functional outcomes, yielding either beneficial adaptive plasticity or detrimental maladaptive plasticity with significant implications for behavioral outcomes. Adaptive plasticity refers to neural changes that enhance an organism's fit to its environment, improving function and supporting recovery after injury [17] [18]. In contrast, maladaptive plasticity describes neural reorganization that disrupts function, potentially leading to pathological states and behavioral impairments [19] [20]. This dichotomy mirrors concepts in evolutionary biology, where phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in different environments—can be locally adaptive, maladaptive, or neutral [21]. Understanding the mechanisms that determine whether plastic changes yield adaptive or maladaptive outcomes is crucial for developing targeted interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The distinction between these plasticity outcomes extends beyond simple beneficial versus harmful changes. As demonstrated in evolutionary biology, the adaptive value of plasticity depends critically on the nature of the trait being measured and its relationship to fitness [21]. Similarly, in neuroscience, the same plastic mechanism may produce adaptive outcomes in one context and maladaptive consequences in another, depending on environmental factors, timing, and neural circuitry involved. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms, manifestations, and experimental approaches for distinguishing these two faces of neuroplasticity, with particular emphasis on implications for drug development and therapeutic interventions.

Fundamental Mechanisms: Structural and Functional Bases

Forms of Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity encompasses multiple mechanisms operating at different spatial and temporal scales. Structural neuroplasticity refers to physical changes in neural circuits, including the growth of new dendritic spines, axonal sprouting, synaptic formation, and even neurogenesis—the generation of new functional neurons primarily in the subventricular zone and hippocampal dentate gyrus [16]. These structural changes provide the physical foundation for long-term neural reorganization. In contrast, functional neuroplasticity involves changes in the strength, efficiency, and synchrony of synaptic connections without immediate structural alterations [16]. This includes mechanisms such as long-term potentiation (LTP), which strengthens synaptic connections through repeated stimulation, and long-term depression (LTD), which weakens less-used connections [16]. Both forms work in concert to enable the brain's dynamic adaptation to experience, injury, and environmental demands.

The process of adaptive plasticity follows a characteristic sequence of events. Initially, the brain undergoes chemical changes, increasing or decreasing neurotransmitter release to facilitate short-term learning [17]. With sustained activity, these chemical changes lead to structural modifications as new connections form between neurons that weren't previously linked [17]. Finally, functional changes occur as entire networks of brain activity reorganize, making the learned action more efficient and automatic [17]. This progression from chemical to structural to functional change exemplifies how repeated experience physically sculpts the brain's organization, as dramatically demonstrated by London taxi drivers who develop enlarged hippocampi—a brain region critical for spatial navigation—after memorizing the city's complex street layout [17].

Molecular Mediators of Plasticity

At the molecular level, neuroplasticity involves complex signaling pathways and molecular determinants. Delta-type ionotropic glutamate receptors (GluDs) play a crucial role in synaptic formation and signaling between neurons [22]. These proteins house charged particles that help bind neurotransmitters, facilitating interneuronal communication at synapses [22]. Mutations in GluD proteins are implicated in psychiatric conditions including anxiety and schizophrenia, with underactivity associated with schizophrenia and hyperactivity linked to cerebellar ataxia [22]. Other critical molecular players include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports neuronal survival and differentiation, and immediate early genes (IEGs) that act as rapid-response elements in synaptic plasticity [23]. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway serves as a central regulator of protein synthesis-dependent plasticity, with increased phosphorylated mTOR in serotonergic spinally projecting neurons observed in neuropathic pain models [19].

Table 1: Key Molecular Determinants of Plasticity Outcomes

| Molecule/Pathway | Function in Plasticity | Associated Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| GluD receptors | Synapse formation, neuronal signaling | Cerebellar ataxia (hyperactivity), schizophrenia (hypoactivity) |

| mTOR pathway | Protein synthesis, synaptic growth | Neuropathic pain (maladaptive), learning (adaptive) |

| BDNF/TrkB signaling | Neuronal survival, differentiation | Adaptive learning and memory |

| Immediate Early Genes (IEGs) | Rapid genomic response to stimulation | Required for classic psychedelic neuroplasticity |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Extracellular matrix remodeling | Neuropathic pain development |

Maladaptive Plasticity: Mechanisms and Pathological Consequences

Neuropathic Pain and Central Sensitization

Maladaptive plasticity manifests prominently in neuropathic pain conditions, where injury to the sensory nervous system triggers plastic changes that paradoxically amplify pain signaling rather than restoring normal function [19]. This condition affects 4-8% of the population and presents with allodynia (pain from normally non-painful stimuli), hyperalgesia (heightened pain response), and spontaneous pain [19]. The maladaptive changes occur along the entire sensory pathway, from peripheral nociceptors to central processing regions. In the peripheral nervous system, upregulation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) channels lowers activation thresholds, increasing sensitivity to thermal and chemical stimuli [19]. Central sensitization involves structural and functional changes in the spinal cord and brain, including microglial activation, increased expression of toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR4), and enhanced synaptic efficacy in pain-processing pathways [19].

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region involved in pain perception, exhibits maladaptive plasticity through upregulation of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) following nerve injury [19]. This change contributes to the affective component of chronic pain. Similarly, the descending pain modulatory system in the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) shows increased phosphorylation of mTOR in serotonergic neurons after spared nerve injury, enhancing excitatory synaptic transmission and intrinsic neuronal excitability that maintains pain states [19]. Administration of rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, reverses these changes and produces analgesic effects, highlighting the potential for targeting maladaptive plasticity therapeutically [19].

Phantom Limb Phenomena and Cortical Reorganization

Another striking example of maladaptive plasticity occurs in phantom limb pain, where amputation leads to persistent perceptions of the missing limb, often accompanied by painful sensations [20]. This phenomenon results from extensive cortical reorganization in the primary somatosensory cortex, wherein areas that previously received input from the amputated limb become responsive to stimulation from adjacent body regions [20]. The degree of cortical reorganization correlates with the intensity of phantom pain, demonstrating a direct relationship between maladaptive neural rewiring and pathological perception. Functional neuroimaging studies reveal that the cortical representation of the face (immediately adjacent to the hand representation in the somatosensory homunculus) expands into the territory previously occupied by the amputated hand, such that touching the face is perceived as sensation in the missing hand [20].

Maladaptive plasticity also underlies tinnitus, where hearing loss triggers compensatory changes in central auditory pathways that generate phantom auditory perceptions [20]. Similarly, in dystonia, repetitive movements lead to abnormal sensorimotor integration and loss of inhibitory control, resulting in sustained muscle contractions and abnormal postures [20]. These examples share a common theme: initial injury or altered input triggers plastic mechanisms that normally support adaptation, but in these cases, the reorganization produces pathological outcomes that impair rather than improve function.

Adaptive Plasticity: Mechanisms and Beneficial Outcomes

Learning, Memory, and Skill Acquisition

Adaptive plasticity serves as the neural foundation for learning and memory across the lifespan [16]. The process follows a well-defined sequence beginning with chemical changes that support short-term memory, progressing to structural changes that establish new neural connections, and culminating in functional changes that make the learned skill automatic and efficient [17]. Myelination—the addition of protective sheathing around nerve fibers—plays a crucial role in this process by increasing the speed and efficiency of neural signaling [17]. With repeated practice, myelin accumulates around frequently used circuits, making skilled performance increasingly automatic. This process explains why London taxi drivers develop enlarged hippocampi and why blind individuals reading Braille show expansion in tactile processing regions [17].

The developmental period represents a time of exceptionally high adaptive plasticity, characterized by rapid synaptogenesis followed by experience-dependent pruning that refines neural circuits [16]. During critical periods, environmental input powerfully shapes neural organization, allowing children to acquire language and other skills with remarkable efficiency [16]. Though plasticity decreases with age, the adult brain retains significant capacity for adaptive change, as demonstrated by recovery from brain injury where undamaged regions can take over functions from affected areas [18]. Engaging in targeted therapy and rehabilitation can enhance this adaptive plasticity, promoting better functional outcomes [18].

Cross-Modal Reorganization and Compensation

Adaptive plasticity enables remarkable cross-modal reorganization in sensory systems, where loss of one modality triggers compensatory enhancement in remaining senses [20]. Blind individuals demonstrate expansion of visual cortical areas that become responsive to auditory and tactile stimuli, leading to genuine perceptual enhancements in hearing acuity and tactile discrimination [20]. These changes support improved Braille reading and auditory localization abilities. Similarly, deaf individuals show enhanced peripheral visual processing and motion detection in visual cortex, adapting to rely more heavily on visual information for communication and spatial awareness [20]. These cross-modal changes reflect the brain's inherent capacity to reallocate computational resources based on environmental demands and available inputs.

The potential for adaptive plasticity is influenced by multiple factors including age, overall health, genetic background, and environmental enrichment [16]. Physical activity, cognitive engagement, and environmental complexity have been shown to enhance neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, particularly in the hippocampus where new neurons contribute to learning and memory processes [16]. Non-pharmacological lifestyle interventions leveraging these principles can promote adaptive plasticity and maintain cognitive function throughout the lifespan, potentially counteracting age-related neurodegenerative processes [16].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Assessing Plasticity in Model Systems

Research into neuroplasticity employs diverse methodological approaches across multiple model systems. Reciprocal transplant experiments, borrowed from evolutionary biology, provide powerful insights into adaptive potential by transplanting individuals between different environments and measuring resulting trait changes [21]. However, interpreting these experiments requires careful consideration of whether measured traits are locally adaptive or simply correlated with fitness, as fitness-correlated traits may show flat reaction norms despite significant adaptive plasticity in unobserved traits [21]. In marine isopod studies, for instance, reciprocal transplantation between high- and low-salinity environments revealed that flat reaction norms for survival and growth likely reflected phenotypic buffering rather than absence of plasticity, demonstrating the importance of measuring multiple traits with known relationships to fitness [21].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Neuroplasticity

| Methodology | Application | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Reciprocal transplant designs | Assessing genotype-environment interactions | Distinguishing adaptive from neutral plasticity |

| Cryo-electron microscopy | Structural analysis of synaptic proteins | Revealing GluD receptor activation mechanisms |

| Genetic and pharmacological tools | Manipulating specific plasticity pathways | Establishing causal roles (e.g., mTOR in pain) |

| Reaction norm analysis | Quantifying phenotypic responses | Differentiating types of plasticity outcomes |

| Functional neuroimaging | Mapping cortical reorganization | Correlating neural changes with behavior |

In laboratory settings, in silico simulations of evolution demonstrate how adaptive plasticity can emerge even when selected against in individual environments [24]. These models incorporate linear reaction norms to simulate how populations evolve plastic responses to temporal environmental heterogeneity [24]. The simulations reveal that limited genetic change per environment (low "learning rate") actually promotes the evolution of adaptive plasticity by preventing populations from completely adapting to each current environment before the next environmental shift [24]. This explains how adaptive plasticity can evolve without lineage selection or individual-level selection for plasticity, occurring instead as a by-product of inefficient short-term natural selection [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Tabernanthalog (TBG) | Nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogen | Promoting neuroplasticity without IEG activation |

| Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) | Thymidine analog for birth-dating cells | Identifying newly generated neurons |

| Rapamycin | mTOR pathway inhibitor | Reversing maladaptive plasticity in pain models |

| TRPV1 modulators | Targeting peripheral sensitization | Investigating neuropathic pain mechanisms |

| Genetic tools (Cre-Lox, RNAi) | Cell-specific manipulation | Dissecting circuit-specific plasticity mechanisms |

| Cryo-EM technologies | High-resolution structural biology | Characterizing synaptic protein structures |

Advanced genetic and pharmacological tools enable precise manipulation of plasticity mechanisms. For example, tabernanthalog (TBG), a nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogen, promotes cortical neuroplasticity through 5-HT2A, TrkB, mTOR, and AMPA receptor activation but without inducing immediate early gene activation or the glutamate burst associated with classic psychedelics [23]. This dissociation of neuroplastic effects from hallucinogenic properties highlights the potential for developing safer plasticity-promoting therapeutics. Similarly, region-specific manipulation of mTOR signaling using rapamycin or genetic approaches has demonstrated the pathway's critical role in maladaptive plasticity underlying neuropathic pain [19]. Toll-like receptor (TLR) antagonists and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors provide additional tools for targeting specific aspects of maladaptive plasticity in neurological disorders.

Signaling Pathways and Neural Circuits

The molecular pathways governing neuroplasticity outcomes involve sophisticated signaling networks that integrate environmental information with neural responses. The following diagram illustrates key pathways differentiating adaptive and maladaptive plasticity:

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways differentiating adaptive and maladaptive plasticity. Note the overlapping molecular players (GluD receptors, psychoplastogens) that can influence both pathways, with outcomes determined by regulation and context.

The experimental workflow for investigating these pathways combines multiple approaches, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for investigating plasticity mechanisms, combining molecular, structural, functional, and behavioral approaches.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Plasticity in Drug Development

Understanding the duality of plasticity opens promising avenues for therapeutic intervention. Psychoplastogens—compounds that promote rapid neuroplasticity—represent an emerging class of therapeutics with potential for treating psychiatric and neurological disorders [23]. Tabernanthalog (TBG), a nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogen, promotes cortical neuroplasticity through 5-HT2A, TrkB, mTOR, and AMPA receptor activation but without inducing immediate early gene activation or the glutamate burst associated with classic psychedelics [23]. This dissociation of neuroplastic effects from hallucinogenic properties enables development of potentially safer, more scalable alternatives to psychedelics for conditions including depression, addiction, and possibly neurodegenerative disorders.

Drugs targeting GluD receptors offer another promising direction, as these proteins directly regulate synapse function and are implicated in schizophrenia, anxiety, and cerebellar ataxia [22]. In schizophrenia, where GluDs are underactive, drugs that enhance GluD activity might restore synaptic function, while in cerebellar ataxia, where GluDs become hyperactive, blockers could normalize signaling [22]. Similarly, targeting mTOR signaling with rapamycin analogs shows potential for normalizing maladaptive plasticity in neuropathic pain [19]. The key therapeutic challenge lies in developing interventions that selectively enhance adaptive plasticity while suppressing maladaptive changes, requiring exquisite temporal and spatial precision.

Timing, Context, and Individual Factors

Therapeutic harnessing of neuroplasticity must account for critical periods and individual differences in plasticity capacity. During development, heightened plasticity enables rapid learning but also creates vulnerability to adverse experiences that can produce maladaptive outcomes [16]. In adulthood, plasticity becomes more constrained but remains modifiable through targeted interventions. Factors including age, genetics, environmental context, and neurological history all influence an individual's plastic potential [18]. Successful interventions will likely require personalized approaches that consider these variables while strategically timing interventions to coincide with periods of heightened plasticity.

Future research directions should focus on identifying biomarkers of plasticity outcomes to predict individual responses to plasticity-targeting interventions. Developing circuit-specific modulators will enable more precise targeting of pathological plasticity while sparing adaptive processes. Combining pharmacological and experiential approaches may yield synergistic benefits, as drugs that enhance plasticity potential could increase the effectiveness of behavioral therapies and rehabilitation. Finally, exploring how principles of evolutionary biology inform neuroplasticity may reveal novel therapeutic strategies for steering plastic changes toward adaptive outcomes [24] [20].

Neuroplasticity embodies a fundamental double-edged sword in neural function and behavioral outcomes. The same mechanisms that enable learning, memory, and recovery from injury can, when dysregulated, produce pathological states including chronic pain, tinnitus, and movement disorders. Distinguishing adaptive from maladaptive plasticity requires integrated analysis across molecular, structural, functional, and behavioral levels, with careful consideration of environmental context and individual differences. Current research is unraveling the complex signaling pathways and circuit mechanisms that determine plasticity outcomes, paving the way for innovative therapeutics that can selectively enhance adaptive plasticity while suppressing maladaptive consequences. As our understanding of these processes deepens, we move closer to precisely harnessing the brain's remarkable plastic capacity to treat neurological and psychiatric disorders, ultimately improving behavioral outcomes and quality of life for affected individuals.

The traditional view of the brain as a static organ with fixed circuitry has been fundamentally overturned. Research now reveals a highly dynamic system capable of large-scale reorganization throughout life, a process central to behavioral adaptation and optimal performance. Large-scale neural network reorganization refers to the brain's capacity to reconfigure its functional and structural connectivity in response to experience, learning, or injury. This whitepaper synthesizes cutting-edge research on the mechanisms, measurement, and functional implications of these reorganizational processes, providing a scientific framework for researchers and drug development professionals exploring the neural basis of adaptive behavior.

Underpinning this capacity for reorganization is neuroplasticity—the brain's biological ability to change its structure and function. Once believed limited to early development, neuroplasticity operates across multiple scales, from molecular and synaptic changes to system-level network reconfiguration [25]. This dynamic architecture enables the brain to maintain stability while retaining the flexibility necessary for learning new skills, recovering from injury, and adapting to changing environments—foundational requirements for optimal behavioral performance [26].

Mechanisms of Large-Scale Reorganization

The brain employs distinct biological mechanisms to achieve reorganization across different spatial and temporal scales. Understanding these processes provides critical insights for developing interventions aimed at modulating neural plasticity.

Synaptic and Structural Plasticity

At the most fundamental level, synaptic plasticity enables experience-dependent strengthening or weakening of connections between neurons. Long-term potentiation (LTP), a persistently strengthened synaptic connection based on recent activity patterns, remains the most studied cellular model for learning and memory [25]. LTP exhibits several critical properties:

- State-dependence: Requires simultaneous activation of sending and receiving neurons within approximately 100 milliseconds

- Input specificity: Strengthening of one synapse does not affect other inactive synapses on the same neuron

- Associativity: Strong activation of nearby pathways can help weak stimulation trigger LTP [25]

Recent research has revealed that spontaneous and experience-driven (evoked) synaptic transmissions originate from distinct synaptic sites with separate developmental timelines and regulatory rules, enabling the brain to maintain stable background activity while refining behaviorally relevant pathways [26].

Beyond synaptic strength changes, structural plasticity involves physical remodeling of neuronal connections. Studies using two-photon microscopy reveal that dendritic spines—tiny protrusions that receive synaptic inputs—can form or disappear at rates of 5-10% weekly during normal experience, increasing dramatically during intense learning or after injury [25]. After retinal lesions, up to 90% of spines in the affected visual cortex area may reorganize during recovery.

System-Level Reorganization

Large-scale reorganization extends beyond local circuits to encompass entire brain systems. Following spinal cord injuries in non-human primates, the deafferented hand region of the primary somatosensory cortex (area 3b) undergoes remarkable reorganization, with face inputs expanding into the hand territory over distances of 7-14 mm [27]. Crucially, this cortical reorganization reflects changes at the brainstem level, as selective inactivation of the reorganized cuneate nucleus eliminates observed face expansion in area 3b [27].

Table 1: Mechanisms of Large-Scale Neural Reorganization

| Mechanism | Spatial Scale | Temporal Scale | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Plasticity (LTP/LTD) | Microns (individual synapses) | Milliseconds to hours | Learning and memory formation |

| Structural Remodeling (dendritic spines) | Microns to millimeters | Days to weeks | Circuit refinement and experience-dependent adaptation |

| Neurogenesis | Local circuits | Weeks to months | Learning capacity and pattern separation |

| Cortical Reorganization | Millimeters to centimeters | Weeks to years | Functional recovery after injury and skill acquisition |

| Network Topological Reconfiguration | Whole-brain systems | Seconds to minutes | Adaptive information processing for changing task demands |

Behavioral Timescale Synaptic Plasticity (BTSP)

Recent research has identified Behavioral Timescale Synaptic Plasticity (BTSP) as a distinctive mechanism enabling rapid, one-shot learning. Unlike traditional spike-timing-dependent plasticity, BTSP:

- Does not depend on firing of the postsynaptic neuron

- Is gated by stochastic synaptic input from the entorhinal cortex

- Is effective after single or few trials (one-shot learning)

- Depends on preceding synaptic weight values

- Operates on time scales of seconds, suitable for episodic memory formation [28]

This mechanism creates content-addressable memory with binary synapses, enabling efficient memory storage and recall while reproducing the repulsion effect observed in human memory, where traces for similar items are actively separated to enable differential processing [28].

Experimental Paradigms and Measurement Approaches

Tracking Reorganization with Brain-Computer Interfaces

Brain-computer interface (BCI) paradigms provide exceptional experimental leverage for studying neural reorganization by establishing explicit, controlled mappings between neural activity and behavior. In landmark non-human primate studies, researchers tracked reorganization throughout motor skill learning spanning several weeks [29].

Table 2: Distinct Timescales of Neural Reorganization in Motor Learning

| Learning Phase | Behavioral Improvement | Neural Reorganization Process | Timescale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Learning | Reduction of directional errors | Global reorganization of neural recruitment common to all neurons | Minutes to hours (hundreds of trials) |

| Slow Learning | Increased movement efficiency | Local changes in individual neuron tuning properties | Weeks (tens of thousands of trials) |

Experimental Protocol: Monkeys performed a center-out cursor task using a BCI that linearly mapped firing rates of primary motor cortex neurons to cursor velocity. Researchers implemented a perturbation by rotating the "pushing directions" of neuron subsets, then tracked how neural tuning properties changed throughout learning. Decoding parameters were estimated through calibration sessions using a coadaptive procedure, with spikes binned into 33-ms intervals, converted to firing rates, normalized, and smoothed with a boxcar filter over previous five time bins [29].

Network Topology Analysis in Sensory Cortex

Research investigating how primary visual cortex (V1) reorganizes during multimodal stimulation demonstrates how sensory systems reconfigure their functional connectivity based on processing demands. Using in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in awake mice, scientists recorded population activity in V1 during unimodal visual and bimodal visuotactile stimulation [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Animal Preparation: Adult C57BL/6J mice (6-8 weeks) received AAV9-hSyn-GCaMP6f viral vector injections into V1 for calcium indicator expression

- Imaging: Two-photon microscopy recorded hundreds of neurons simultaneously in awake mice during stimulation

- Stimulation Paradigm: Unimodal (visual gratings) and bimodal (visual gratings + whisker deflection) stimuli

- Network Construction: Functional connectivity networks built from fluorescence time series

- Quantitative Analysis: Graph-theoretical metrics computed including betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, degree centrality, global efficiency, and modularity [30]

Findings revealed that unimodal visual processing relies on hub-centric, modular architectures, while cross-modal input promotes globally integrated, distributed networks with higher connectivity efficiency. This topological reconfiguration represents an adaptive mechanism for balancing local specialization with global integration based on sensory context [30].

Causal Intervention Approaches

Establishing causal relationships in neural reorganization requires direct intervention methods. Research on somatosensory reorganization after spinal cord injury employed selective neural inactivation to identify critical sites of plasticity [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Animal Model: Macaque monkeys with unilateral dorsal column lesions at cervical levels (C4/C5)

- Chronic Preparation: Cortical and brainstem mapping 14-36 months post-lesion

- Neural Inactivation:

- Cortical Test: Lidocaine (4%) infusion into normal chin representation of area 3b

- Brainstem Test: Lidocaine injection into reorganized cuneate nucleus at multiple sites (2-4μl per site at 4μl/min)

- Simultaneous Recording: Multiunit activity recorded in both area 3b and brainstem nuclei during tactile stimulation (1Hz, 10ms skin contact) [27]

Results demonstrated that inactivation of the reorganized cuneate nucleus—but not the original cortical face representation—eliminated expanded chin responses in deafferented cortex, establishing brainstem plasticity as the substrate for large-scale cortical reorganization [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Neural Reorganization Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| AAV9-hSyn-GCaMP6f | Genetically-encoded calcium indicator for neuronal activity visualization | Monitoring population activity in mouse primary visual cortex during multimodal stimulation [30] |

| Tungsten Microelectrodes | Extracellular recording of single or multiunit activity | Mapping somatotopic organization in primate somatosensory cortex and brainstem nuclei [27] |

| Lidocaine HCl (4%) | Sodium channel blocker for reversible neural inactivation | Causal testing of plasticity sites in cortical and brainstem structures [27] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | High-resolution imaging of neuronal population activity | Recording hundreds of neurons simultaneously in awake, behaving mice [30] |

| Utah Multielectrode Arrays | Chronic recording from neuronal populations | Tracking motor cortex reorganization during long-term BCI learning [29] |

| Chubbuck Vibratory Stimulator | Precise tactile stimulation with controlled parameters | Mapping receptive fields in somatosensory pathways [27] |

Theoretical Frameworks: Prospective Configuration

The prospective configuration model offers a fundamentally different principle for understanding how the brain solves credit assignment problems during learning. Unlike backpropagation—which modifies weights first, leading to subsequent changes in neural activity—prospective configuration first infers the pattern of neural activity that should result from learning, then modifies synaptic weights to consolidate this change [31].

This mechanism naturally emerges from energy-based networks (including Hopfield networks and predictive coding networks), where neural activity and weights represent movable parts in a dynamical system that minimizes an energy function. The model reproduces surprising patterns of neural activity and behavior observed in diverse learning experiments while enabling more efficient learning in contexts faced by biological organisms, including continual learning and rapidly changing environments [31].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Understanding large-scale neural reorganization provides crucial insights for developing interventions targeting neurological and psychiatric conditions. Abnormalities in synaptic signaling and plasticity mechanisms have been implicated in autism, Alzheimer's disease, and substance use disorders [26]. The separation of spontaneous and evoked transmission sites reveals potential therapeutic targets for modulating specific aspects of neural signaling without disrupting overall system function.

The BRAIN Initiative has identified advancing human neuroscience and developing innovative technologies to understand and treat brain disorders as key priorities [32]. Research consenting humans undergoing diagnostic brain monitoring or receiving neurotechnology for clinical applications provides extraordinary opportunities to understand human-specific reorganization mechanisms and test novel interventions [32].

Future directions include leveraging knowledge of large-scale reorganization to develop:

- Targeted neuromodulation approaches that guide adaptive plasticity while minimizing maladaptive reorganization

- Pharmacological agents that enhance beneficial plasticity mechanisms at specific organizational levels

- Rehabilitation protocols that optimally engage endogenous plasticity mechanisms through carefully timed intervention schedules

- Brain-computer interfaces that harness reorganization capacity to restore function after neurological injury

The dynamic, multi-scale nature of neural reorganization presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development, requiring approaches that consider interactions across molecular, cellular, circuit, and system levels.

Harnessing Neuroplasticity: Research Methods and Therapeutic Applications

Neuroplasticity, the nervous system's capacity to reorganize itself in response to experience and injury, serves as the fundamental biological substrate for behavioral adaptation and optimal performance [3] [33]. This dynamic process spans multiple spatial and temporal scales, from molecular and synaptic changes to large-scale network reorganization [32] [34]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing interventions to enhance cognitive function, promote resilience, and facilitate recovery from neurological disorders. The assessment of neuroplastic change requires sophisticated technologies that can capture the brain's structural and functional dynamics non-invasively in humans. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and associated biomarkers now provide unprecedented windows into these processes, enabling researchers to quantify how neural circuits adapt throughout the lifespan [32] [33] [35].

Within the context of behavioral adaptation and optimal performance research, tracking neuroplastic changes is essential for understanding how individuals acquire skills, adapt to challenging environments, and maintain cognitive function. The BRAIN Initiative has identified the analysis of circuits of interacting neurons as particularly rich in opportunity, with potential for revolutionary advances in understanding how dynamic patterns of neural activity are transformed into cognition, emotion, perception, and action [32]. Continuous and real-time neural modifications in concert with dynamic environmental contexts provide opportunities for targeted interventions for maintaining healthy brain functions throughout the lifespan [3]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of advanced assessment techniques for tracking these plastic changes, with specific emphasis on their application to optimal performance research.

fMRI Methodologies for Tracking Plastic Change

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Functional MRI measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood oxygenation and flow, providing an indirect marker of neural activity with high spatial resolution. This technique enables researchers to map neural circuits and observe how they reorganize in response to experience, training, or intervention [32] [36]. For plasticity research, fMRI can capture both rapid and long-term changes in brain function, including alterations in network connectivity, expansion or contraction of cortical representations, and shifts in activation patterns associated with skill acquisition [32].

The value of fMRI in neuroplasticity research lies in its ability to generate circuit diagrams that vary in resolution from synapses to the whole brain, enabling an understanding of the relationship between neuronal structure and function [32]. Advanced fMRI techniques now allow researchers to produce a dynamic picture of the functioning brain through large-scale monitoring of neural activity, capturing how circuits interact at the speed of thought [32]. When integrated with other modalities, fMRI provides a comprehensive view of how experience shapes brain organization across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Experimental Protocols for Plasticity Assessment

Task-Based fMRI Protocol for Skill Acquisition:

- Experimental Design: Implement block or event-related designs with appropriate baseline conditions. For motor skill acquisition, use sequential finger tapping tasks; for cognitive training, employ working memory or attentional tasks.

- Scanning Parameters: Acquire T1-weighted structural images (MPRAGE sequence, 1mm isotropic resolution) and T2*-weighted functional images (EPI sequence, 2-3mm isotropic resolution, TR=2000ms, TE=30ms).