Optimizing Brain Performance: Neurobiological Mechanisms, Pharmacological Interventions, and Future Directions

This article synthesizes current neurobiological research on optimizing brain performance for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Optimizing Brain Performance: Neurobiological Mechanisms, Pharmacological Interventions, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article synthesizes current neurobiological research on optimizing brain performance for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore foundational mechanisms of adaptive neurobiological plasticity, including how enriched environments and behavioral interventions build cognitive reserve. The review critically evaluates methodological approaches for enhancing cognition, from established pharmacological agents targeting neuromodulatory systems to emerging non-pharmacological strategies like targeted exercise and social playfulness. We address significant troubleshooting challenges in the field, including the variable efficacy of cognitive enhancers and risks associated with their use in developing brains. Finally, we examine validation paradigms and comparative effectiveness across intervention modalities, concluding with integrated perspectives on future research directions for developing safe, effective, and personalized approaches to cognitive enhancement.

Foundational Mechanisms of Adaptive Neurobiological Plasticity

Defining Optimal Brain Performance in Goal-Directed Contexts

Optimal brain performance in goal-directed behaviors is an emergent property of integrated neural systems functioning in concert. This whitepaper synthesizes contemporary neuroscience research to define the core mechanisms—spanning molecular, circuit, and computational levels—that enable efficient goal pursuit. We examine the neural substrates of goal-directed navigation as a canonical model system, detailing the dynamic interplay between cognitive strategies, their neural implementations, and the measurable outputs that define optimal performance. The framework presented herein offers researchers a structured approach for quantifying brain performance and developing targeted interventions.

Goal-directed behavior represents a principal higher-order brain function, requiring the coordinated engagement of multiple cognitive domains including planning, decision-making, execution, and adaptation. From a neurobiological perspective, optimal performance is not merely the absence of deficit but the efficient integration of neural processes to achieve desired outcomes with minimal resource expenditure. The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative outlines a comprehensive scientific vision, emphasizing that understanding the brain in action requires spanning analyses from molecules and cells to circuits, systems, and behavior [1]. This multi-scale approach is fundamental to defining and measuring optimal performance.

Central to this framework is the concept that the brain's reward system, governed by neurotransmitters like dopamine, reinforces successful behaviors [2]. Accomplishing a goal, however small, triggers dopamine release, creating a sense of pleasure and cementing the neural pathways that led to that success. This biochemical mechanism establishes a positive feedback cycle crucial for sustained goal pursuit. Furthermore, performance is underpinned by neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This allows for continuous skill development and behavioral adaptation based on experience [2]. This whitepaper will dissect these and other core components, providing a technical guide for researchers aiming to quantify and enhance goal-directed brain performance.

Core Neural Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Goal-directed behavior is supported by distinct but interacting neural systems. The following table summarizes the key brain structures and their primary functions in this context.

Table 1: Key Neural Substrates in Goal-Directed Behavior

| Brain Structure | Primary Function in Goal-Directed Behavior |

|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Executive control, integrating sensory and mnemonic information, regulating goal-selection, planning, and decision-making [2]. |

| Hippocampus | Critical for forming and retrieving cognitive maps, enabling spatial and relational memory necessary for navigation and planning [3]. |

| Striatum | Central to reinforcement learning, habit formation, and linking actions to rewarding outcomes [3]. |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) | Performance monitoring, conflict detection, and adjustment of cognitive control, particularly during challenging tasks [2]. |

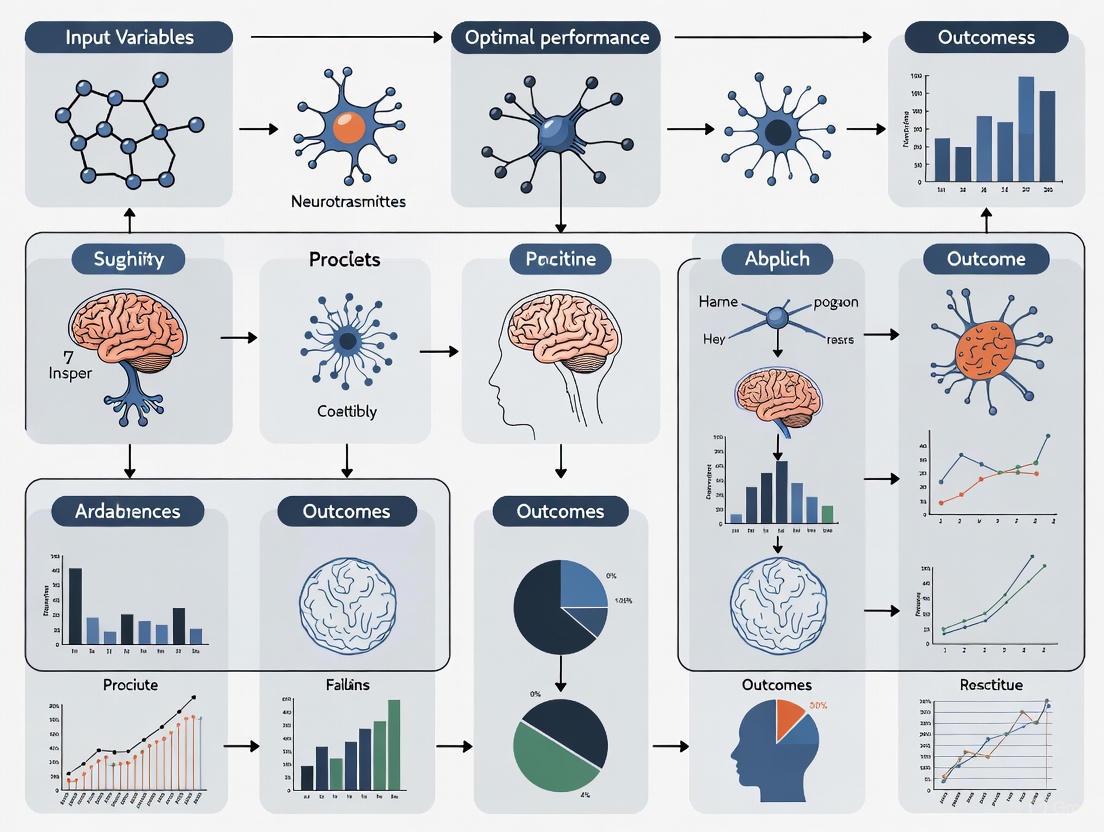

The interaction between these regions is governed by specific signaling pathways. The diagram below illustrates the primary neural pathway engaged during the planning and execution of a goal-directed action.

Diagram Title: Neural Circuit for Goal-Directed Action

Information Processing and Computational Strategies

The brain employs sophisticated computational strategies to solve goal-directed problems. Research on navigation in novel environments reveals that humans meta-learn an adaptive policy, flexibly switching between two primary strategies [3]:

- Vector-Based Navigation: A geometric strategy where agents compute the direction and distance (vector) to a goal from their current location. This relies on a Euclidean cognitive map, often linked to hippocampal-entorhinal systems and grid cell activity, and is optimal for inferring novel shortcuts [3].

- State Transition-Based Navigation: A topological strategy where agents use learned associations between successive states (e.g., which paths connect to which). This is implemented through the brain's capacity to predict state transitions and is optimal for navigating well-learned, cluttered environments [3].

Notably, deep neural networks trained with reinforcement learning (RL) to solve novel navigation problems develop units specialized for each strategy, mirroring human performance and suggesting these strategies represent a fundamental solution for few-shot learning in partially observable environments [3]. The diagram below outlines the experimental workflow used to elucidate these strategies.

Diagram Title: Navigation Strategy Experiment Workflow

Quantifying Neural Information Processing

Information theory provides a powerful, model-independent framework for quantifying how neural systems encode and process task-relevant data. Mutual information, a core metric, measures how much knowledge of one variable (e.g., neural activity) reduces uncertainty about another (e.g., a stimulus or planned movement) [4]. For example, the information carried by a motor cortex neuron about movement direction can be calculated in bits, analogous to the number of yes/no questions needed to ascertain the variable's value. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing multivariate neural data and capturing nonlinear interactions that traditional model-dependent analyses might miss [4].

Table 2: Key Information Theory Metrics for Neural Data Analysis

| Metric | Formula/Concept | Application in Goal-Directed Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy (H) | ( H(X) = - \sum p(x) \log_2 p(x) ) | Measures the total uncertainty or information capacity of a neural signal. | |

| Mutual Information (MI) | ( I(X;Y) = H(X) + H(Y) - H(X,Y) ) | Quantifies how much information a neural response conveys about a specific stimulus, decision, or action [4]. | |

| Transfer Entropy (TE) | ( TE{X \to Y} = I(Y{t+1}; X_t | Y_t) ) | A directional, dynamic measure of information flow, useful for assessing functional connectivity between brain regions during a task [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Goal-Directed Performance

This section details a key experimental paradigm adapted from recent research investigating navigation strategies [3].

Protocol: Few-Shot Navigation in Novel Environments

Objective: To dissect the cognitive strategies and neural correlates of goal-directed planning in novel environments using a meta-learning approach.

Participants:

- Human cohort: 401 participants (as per the cited study) [3].

- Model cohort: Deep neural networks trained with reinforcement learning (e.g., Proximal Policy Optimization) [3].

Materials and Setup:

- An 8x8 grid-based virtual environment.

- Unique object images for each grid square, with specific objects designated as landmarks and goal.

- Standard computer equipment for human participants; GPU-accelerated computing clusters for model training.

Procedure:

- Map Reading Phase: Participants are shown a bird's-eye view of the grid with all objects obscured. They sequentially click on blue squares to reveal landmark objects for 3 seconds each (16 exposures total). Finally, they click a yellow square to reveal the goal object.

- Navigation Phase: Participants are placed at a random starting location within the grid. On each step, they choose to either:

- Option A (Vector-Based): Select a cardinal direction to move in.

- Option B (Transition-Based): Select a specific adjacent state to move to.

- The trial concludes when the participant reaches the goal location. A new trial with a completely novel environment (layout, objects, goal) begins.

Data Analysis:

- Behavioral Modeling: Fit computational models to choice data to quantify the relative reliance on vector-based vs. state transition-based strategies at different stages of the journey and in relation to landmark proximity.

- Neural Correlates (fMRI/EEG): Identify brain activity patterns associated with the deployment of each strategy, with a focus on hippocampus, PFC, and striatum.

- AI-Human Comparison: Analyze the policies developed by RL agents for strategic convergence with human behavior and examine the representational geometry of hidden layer units for grid-like and place-cell-like activity [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents, tools, and methodologies for research in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Goal-Directed Neuroscience

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Neurofeedback with EEG | Real-time monitoring of brainwave patterns allows subjects to learn self-regulation of mental states. | Optimizing states of focus and relaxation to enhance cognitive performance before or during task execution [2]. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Non-invasive measurement of brain activity via blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals. | Mapping large-scale brain network engagement (PFC, hippocampus, striatum) during planning and navigation tasks [4]. |

| Optogenetics/Chemogenetics (DREADDs) | Precise manipulation of neural circuit activity using light or engineered receptors. | Establishing causal links between specific neural populations and goal-directed behaviors in animal models [1]. |

| Information Theory Toolbox | Software package (e.g., Neuroscience Information Theory Toolbox for MATLAB) for calculating entropy, mutual information, and transfer entropy. | Quantifying information encoding in neural spiking data or BOLD signals related to stimuli, decisions, and actions [4]. |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning Models | Trainable neural networks that meta-learn policies for complex tasks. | Serves as a testable computational model of human cognition, generating hypotheses about neural representation and strategy use [3]. |

| Calcium Imaging | Fluorescence-based recording of neural activity in vivo with high cellular resolution. | Monitoring the dynamics of large neural populations in model organisms during the learning and execution of goal-directed tasks. |

Defining optimal brain performance in goal-directed contexts requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates molecular, systems, and computational neuroscience. The evidence indicates that optimal performance is characterized by the brain's capacity to dynamically arbitrate between complementary cognitive strategies, leverage dopaminergic reinforcement, and maintain cognitive control through prefrontal circuits. The convergence of human and artificial intelligence research offers a particularly promising path forward, suggesting that the strategies we observe are robust solutions to the problem of efficient navigation in uncertain environments.

Future research must focus on bridging levels of analysis, linking molecular mechanisms within specific cell types to the computations they enable at the circuit and systems level. The BRAIN Initiative 2025 report emphasizes this, calling for the integration of technologies to discover "how dynamic patterns of neural activity are transformed into cognition, emotion, perception, and action" [1]. By leveraging the experimental protocols and tools outlined in this whitepaper, researchers and drug development professionals can work towards a unified model of optimal brain function, paving the way for precise interventions that enhance cognitive performance in health and disease.

While adult neurogenesis represents one facet of brain adaptability, neuroplasticity encompasses a far broader spectrum of structural and functional mechanisms through which the nervous system reorganizes itself. This whitepaper details the diverse manifestations of neuroplasticity beyond new neuron generation, focusing on synaptic remodeling, circuit-level reorganization, and large-scale network adaptations. We frame these complex processes within a neurobiological framework for optimal brain performance research, providing methodologies for investigating these phenomena and discussing their implications for therapeutic development. The content is structured to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical understanding of non-neurogenic plasticity, its experimental investigation, and its potential as a target for cognitive enhancement and neurological disorder treatment.

Neuroplasticity is fundamentally defined as the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections [5]. This capacity extends far beyond the generation of new neurons in classical neurogenic niches like the hippocampus and subventricular zone. A more nuanced understanding recognizes that plasticity operates across multiple spatial and temporal scales, from molecular changes at individual synapses to the reorganization of entire functional networks [1] [6].

For research aimed at optimizing brain performance, it is crucial to appreciate that neuroplasticity is not universally beneficial; its outcomes can be adaptive, neutral, or maladaptive depending on context [5]. The field is now moving toward a more comprehensive vector model of plasticity, where changes can be categorized as "upward neuroplasticity" (involving synaptic construction and strengthening) or "downward neuroplasticity" (involving synaptic deconstruction and weakening), both representing legitimate and often complementary mechanisms of neural adaptation [6]. This paradigm shift reframes synaptic elimination not as impairment but as an essential physiological process for circuit refinement throughout the lifespan.

This whitepaper systematically explores the principal manifestations of neuroplasticity excluding adult neurogenesis, provides methodological guidance for their investigation, and discusses their implications for therapeutic development in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Core Mechanisms of Non-Neurogenic Plasticity

Synaptic Plasticity

Synaptic plasticity refers to experience-dependent long-lasting changes in the strength of neuronal connections, primarily expressed through long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) [5]. First discovered in 1973 by Bliss and Lomo, LTP involves repetitive stimulation of presynaptic fibers resulting in enhanced responses of postsynaptic neurons, achieved through mechanisms such as adding more neurotransmitter receptors to lower activation thresholds [5]. Beyond classic Hebbian plasticity, contemporary understanding includes more complex mechanisms:

- Spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP): Incorporates the precise timing of action potentials in pre- and postsynaptic neurons to determine whether synapses are strengthened or weakened [5].

- Metaplasticity: Encompasses activity-dependent changes that modify how synapses respond to future plasticity-inducing stimuli, essentially "plasticity of plasticity" [5].

- Homeostatic plasticity: Mechanisms that maintain stability of neuronal and network activity over time through scaling of synaptic strengths [5].

Multiple factors positively influence synaptic plasticity, including exercise, environmental enrichment, task repetition, motivation, neuromodulators (e.g., dopamine), and certain pharmacological agents [5]. Conversely, aging and neurodegenerative diseases are associated with reductions in neuromodulators that may diminish synaptic plasticity capacity [5].

Structural and Connectional Plasticity

Structural plasticity involves physical changes to neuronal morphology, including dendritic branching, spine density, and axonal patterning. Throughout neurodevelopment, an initial overproduction of synapses is progressively refined through activity-dependent pruning, a form of downward neuroplasticity essential for creating precise neural circuits [6]. The human prefrontal cortex continues this developmental remodeling into the third decade of life, representing an extended period of environmental sensitivity and vulnerability to neuropsychiatric disorders [6].

In adulthood, structural plasticity persists at a slower pace, with dendritic spines exhibiting a range of lifespans. In mouse barrel cortex, while approximately 50% of dendritic spines persist for at least a month, the remainder may be present for only a few days [6]. This ongoing structural turnover provides a substrate for continuous learning and memory formation while maintaining overall circuit stability.

Functional Reorganization at Circuit and Network Levels

Following injury or during skill acquisition, the brain demonstrates remarkable capacity for functional reorganization through several key mechanisms:

Equipotentiality and Vicariation: The concepts that undamaged brain regions can support lost functions (equipotentiality) or that brain areas can overtake functions they weren't originally dedicated to (vicariation) [5]. Neuroimaging studies after hemispherectomy or stroke show the remaining cortex can reorganize to restore lost functions, with initial bilateral activation eventually shifting to more focal patterns in compensatory regions [5].

Diaschisis: A concept introduced by von Monakow describing how damage to one brain region can cause functional impairments in distant but connected areas [5]. Modern neuroscientific investigations have expanded this concept to include:

- Functional diaschisis: Remote effects observed only during brain activation

- Connectional diaschisis: Rerouting of information flow after damage

- Connectome diaschisis: Disruption caused by damage to highly connected network hubs [5]

A concrete example is hypoperfusion of the ipsilateral thalamus after middle cerebral artery stroke, occurring in approximately 20% of acute cases and increasing to 86% in subacute and chronic phases, potentially due to disinhibition from lost GABAergic inputs [5].

Table 1: Forms of Functional Reorganization in Neuroplasticity

| Mechanism | Definition | Clinical/Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Equipotentiality | Undamaged brain regions can support functions lost after injury | Preservation of function after early brain injury [5] |

| Vicariation | Brain areas overtake functions not originally their own | Reorganization of supplemental motor areas after stroke [5] |

| Diaschisis "at rest" | Classic von Monakow-type disruption in areas connected to site of injury | Thalamic hypoperfusion after MCA stroke [5] |

| Functional Diaschisis | Remote effects evident only during brain activation tasks | Cerebellar hypoactivation during hand tasks after putamen lesions [5] |

Quantitative Manifestations of Neuroplasticity

Research has quantified neuroplastic changes across multiple domains, providing biomarkers for tracking brain adaptation and targets for therapeutic intervention.

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of Neuroplastic Manifestations

| Plasticity Type | Measurement Approach | Key Quantitative Findings | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Synaptic Pruning | Dendritic spine density analysis | Child's brain has ~1000 trillion synapses, significantly higher than adult levels [6] | Human, non-human primate, rodent |

| Cortical Map Reorganization | fMRI, intracortical recording | Cortical representation areas can shift boundaries in response to experience or injury [6] | Owl monkey, human |

| Structural Turnover | Two-photon microscopy of dendritic spines | ~50% of dendritic spines in adult mouse barrel cortex persist >1 month; remainder last days [6] | Mouse |

| White Matter Plasticity | Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) | Fractional anisotropy changes correlate with skill learning duration and intensity [7] | Human |

| Network Reorganization | Resting-state functional connectivity | Brain network breakdown evident across lifespan; predicts cognitive decline [7] | Human (Dallas Lifespan Brain Study) |

Neuroplasticity in Pathology: Addiction as a Case Study

Substance use disorders provide a powerful model of maladaptive neuroplasticity, where drug-induced changes hijack normal learning and reward mechanisms [8]. The disease model of addiction recognizes it as a chronic brain disorder characterized by significant alterations in brain structure and function, with progression through a three-stage cycle:

- Binge/Intoxication Stage: Involves increased dopamine, opioid peptides, serotonin, GABA, and acetylcholine in reward pathways including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens (NAc) [8].

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: Characterized by increases in corticotropin-releasing factor, dynorphin, and norepinephrine, with decreased dopamine and serotonin in extended amygdala and related structures [8].

- Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: Involves increased glutamate, dopamine, and corticotropin-releasing factor in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala, mediating craving and relapse [8].

Neuroimaging studies reveal specific plasticity-based changes in addiction, including impaired prefrontal cortex function contributing to loss of control, and alterations in reward, stress, and emotional systems [8]. The opponent-process theory further explains how repeated drug use strengthens counteradaptive mechanisms that oppose the drug's initial pleasurable effects, leading to tolerance and withdrawal [9].

Methodologies for Investigating Neuroplasticity

Experimental Protocols for Key Assessments

Protocol 1: Assessing Synaptic Plasticity via Electrophysiology Objective: To measure long-term potentiation (LTP) in hippocampal slices as an indicator of synaptic plasticity. Procedure:

- Prepare 400μm thick transverse hippocampal slices from rodent brain.

- Maintain slices in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid at 32°C.

- Place stimulating electrode in Schaffer collateral pathway and recording electrode in CA1 stratum radiatum.

- Record field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) for 20 minutes to establish baseline.

- Deliver high-frequency stimulation (e.g., 100Hz for 1s) to induce LTP.

- Continue recording fEPSPs for 60+ minutes post-tetanus.

- Quantify LTP as percentage increase in fEPSP slope relative to baseline. Applications: Screening cognitive-enhancing compounds, studying learning mechanisms, modeling disease-related plasticity deficits [5].

Protocol 2: Tracking Structural Plasticity with Two-Photon Microscopy Objective: To monitor dendritic spine turnover in vivo. Procedure:

- Express fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) in sparse neuronal populations using viral vectors or transgenic mice.

- Implant cranial window over region of interest (e.g., cortex).

- Acquire baseline images of dendritic segments at high resolution.

- Return animal to home cage for predetermined interval (days to weeks).

- Re-image same dendritic segments using identical coordinates.

- Align and analyze images to classify spines as persistent, gained, or lost.

- Calculate turnover rates as (gained + lost spines) / (2 × total spines × time) [6]. Applications: Studying experience-dependent plasticity, aging effects, therapeutic efficacy in neurodegenerative models.

Protocol 3: Mapping Functional Reorganization with fMRI Objective: To identify cortical representation changes following injury or training. Procedure:

- Acquire pre-intervention fMRI scans during task performance (e.g., motor task).

- Implement intervention (skill training, induce injury, or study natural recovery).

- Conduct serial post-intervention fMRI sessions using identical paradigms.

- Preprocess data: motion correction, spatial normalization, smoothing.

- Model BOLD response for each session separately.

- Compare activation maps across sessions using whole-brain or ROI analyses.

- Quantify changes in activation intensity, volume, or laterality indices. Applications: Rehabilitation monitoring, brain-computer interface development, understanding compensatory mechanisms [5] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neuroplasticity Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Example Specific Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Neuronal Tracers | Mapping neuronal connectivity and circuit reorganization | Fluoro-Gold, Cholera Toxin B, AAV-based tracers |

| Plasticity Biomarkers | Labeling newly formed or activated synapses | c-Fos (immediate early gene), PSD-95, synaptophysin |

| Neuromodulatory Compounds | Probing neurotransmitter systems in plasticity | Dopamine agonists/antagonists, BDNF, norepinephrine modulators |

| Activity Reporters | Monitoring neural activity in real-time | GCaMP calcium indicators, Arc-GFP reporters, voltage-sensitive dyes |

| Structural Labels | Visualizing neuronal morphology changes | DiOlistics, Golgi-Cox staining, intracellular dye injection |

| Molecular Plasticity Tools | Manipulating specific signaling pathways | CREB inhibitors, TrkB receptor modulators, NMDA receptor antagonists |

Signaling Pathways in Neuroplasticity

Several evolutionarily conserved molecular pathways regulate neuroplasticity mechanisms beyond neurogenesis. The following diagrams illustrate key signaling cascades involved in synaptic modification and structural plasticity.

Diagram 1: Key molecular pathways regulating neuroplasticity. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway promotes synaptic formation and stability. BDNF/TrkB signaling enhances synaptic protection and regulates gene expression. NMDA receptor activation triggers calcium-dependent processes that modify synaptic strength.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for neuroplasticity research. Studies typically progress from baseline measures through intervention to post-intervention assessment, utilizing multiple methodological approaches to capture different facets of plasticity from behavioral to molecular levels.

Emerging Frontiers and Research Vectors

The BRAIN Initiative 2025 report outlines seven major goals that will shape future neuroplasticity research [1]:

- Cell Census: Comprehensive characterization of brain cell types and their roles in health and disease

- Multi-Scale Maps: Circuit diagrams spanning synaptic to whole-brain resolution

- Brain in Action: Large-scale monitoring of neural activity during behavior

- Causal Demonstration: Linking brain activity to behavior through precise interventions

- Fundamental Principles: Developing theoretical frameworks for brain function

- Human Neuroscience: Advancing technologies for understanding human brain disorders

- Integration: Synthesizing technological and conceptual approaches across scales

Emerging technologies are already transforming neuroplasticity research. Ultra-high field MRI (11.7T) provides unprecedented spatial resolution for tracking structural changes [10]. Digital brain models, from personalized simulations to full brain replicas, offer platforms for testing plasticity hypotheses in silico [10]. Large-scale longitudinal datasets like the Dallas Lifespan Brain Study (n=464 with multi-timepoint assessments) enable investigation of individual differences in plasticity trajectories across the adult lifespan [7].

Artificial intelligence applications are accelerating the analysis of complex neuroplasticity data, from automated segmentation of structural changes to identification of predictive biomarkers in large datasets [10]. These advances, coupled with open data sharing initiatives, promise to rapidly expand our understanding of how the brain adapts throughout life and how these mechanisms can be harnessed for cognitive enhancement and neurological recovery.

Neuroplasticity encompasses a far richer repertoire of adaptive mechanisms than traditionally recognized, extending well beyond adult neurogenesis to include synaptic strengthening and weakening, structural remodeling, and large-scale network reorganization. The emerging paradigm of upward and downward neuroplasticity as complementary vectors of brain adaptation provides a more nuanced framework for understanding how neural circuits are refined throughout life.

For researchers and drug development professionals, targeting these diverse plasticity mechanisms offers promising avenues for enhancing brain performance and treating neurological disorders. Future progress will depend on integrating approaches across scales—from molecular manipulations to network-level interventions—while leveraging emerging technologies in neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and computational modeling. As we deepen our understanding of these processes, we move closer to harnessing the brain's inherent plasticity to optimize its function across the lifespan.

Environmental Enrichment and Neural Circuit Modification

Environmental Enrichment (EE) represents a multifaceted, non-invasive intervention capable of inducing measurable structural and functional changes in the neural circuitry of the brain. Framed within the broader thesis of neurobiological research on optimal brain performance, EE serves as a powerful, non-pharmacological paradigm to probe the mechanisms of experience-dependent neural plasticity. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for identifying novel therapeutic targets for neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders. EE is not merely an "improved" housing condition but a controlled experimental protocol that leverages enhanced sensory, cognitive, motor, and social stimulation to foster a specific, beneficial form of neural eustress [11]. This controlled stressor induces adaptive responses, leading to documented changes at molecular, cellular, and systems levels, including altered gene expression, synaptic strength, and ultimately, modified circuit dynamics that underlie behavior [12] [13]. This guide synthesizes current evidence and provides a technical framework for deploying EE in preclinical research aimed at circuit modification.

Neurobiological Mechanisms of Environmental Enrichment

The efficacy of Environmental Enrichment in modifying neural circuits is rooted in its ability to engage a series of cascading biological processes. The overarching mechanism involves the transduction of multimodal external stimuli into internal biochemical and electrical signals that collectively enhance brain plasticity.

Key Signaling Pathways and Neurotrophic Factors

Environmental enrichment triggers several conserved molecular pathways that bridge external stimulation to intracellular changes and synaptic remodeling. The diagram below illustrates the core signaling workflow activated by EE, from sensory input to functional circuit modification.

The activation of these pathways converges to produce measurable cellular and structural changes. The upregulation of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is a cornerstone of EE-induced plasticity. BDNF signaling through its receptor, TrkB (Ntrk2), promotes neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptogenesis. This pathway is highly enriched in EE models, as confirmed by transcriptomic analyses [14]. Concurrently, EE induces the expression of Immediate Early Genes (IEGs) such as Fos, Egr1, and Junb, which serve as markers of neuronal activation and regulators of downstream transcriptional programs supporting long-term plasticity [14]. These molecular changes manifest structurally as increased dendritic branching, spine density, and synaptic potentiation, which collectively provide the physical substrate for modified neural circuit function [12].

Quantitative Evidence: A Meta-Analysis of EE Outcomes

The impact of EE on brain function and circuitry can be quantified through its effects on behavioral and developmental metrics. The following tables summarize key findings from recent clinical and preclinical research, with a particular focus on vulnerable populations where neural circuit plasticity is most salient.

Therapeutic Efficacy of EE in High-Risk Infant Populations

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) evaluated the effects of EE on infants with or at high risk of cerebral palsy (CP) [12]. The results, synthesized below, demonstrate a significant positive effect of EE on key developmental domains.

Table 1: Meta-Analysis of EE Effects on Infant Development (0-24 months) with or at high risk of Cerebral Palsy

| Outcome Domain | Number of Studies | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Motor Development | 14 | 0.35 | 0.11 to 0.60 | p = 0.004 |

| Gross Motor Function | 14 | 0.25 | 0.06 to 0.44 | p = 0.011 |

| Cognitive Development | 14 | 0.32 | 0.10 to 0.54 | p = 0.004 |

| Fine Motor Function | 14 | Not Significant | Not Reported | Not Significant |

Critical Periods for EE Intervention

The same meta-analysis conducted subgroup analyses to identify optimal age windows for intervention, revealing that timing is a critical factor for maximizing therapeutic benefit [12].

Table 2: Optimal Age Windows for EE Intervention Efficacy

| Outcome Domain | Most Effective Age Window | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Development | 6 - 18 months | Significant improvements within this window, which captures a peak period of motor circuit plasticity. |

| Cognitive Development | 6 - 12 months | Strongest effects on cognition observed during this earlier window, aligning with rapid synaptogenesis in associative circuits. |

These quantitative findings underscore that EE is not a one-size-fits-all intervention. Its effectiveness is contingent upon the specific functional domain being targeted and the developmental stage of the subject, a principle that is crucial for designing clinical trials and preclinical research studies.

Experimental Protocols: A Standardized Rodent EE Paradigm

To ensure reproducibility and valid cross-study comparisons, it is essential to adhere to a detailed and consistent EE protocol. The following methodology, adapted from a peer-reviewed video article, provides a robust framework for housing mice in an enriched environment [11].

Detailed Housing and Maintenance Procedures

A. Preparation of the Enriched Environment

- Housing Instrument: Use a large bin (e.g., 120 cm x 90 cm x 76 cm) to provide ample space for exploration and social interaction.

- Cleaning: Run the bin and all plastic toys (igloos, tunnels, tubing) through a standard cage wash cycle (e.g., 5-6 cycles, final cycle at 82°C). Autoclave wooden logs on a dry cycle (121°C for 15 minutes) [11].

- Setup:

- Cover the bin floor with 2-2.5 cm of standard corn cob bedding.

- Arrange enrichment items to encourage exploration:

- Place 2-3 logs in one corner to create a complex shelter.

- Position 3 igloos with integrated saucer wheels within the sheltered area, ensuring wheels can spin freely.

- Assemble plastic tubing with multiple arms in the center of the bin.

- Place 2-3 feeding cages (with 5 cm entry holes) in corners, fitted with wire racks for food and water.

- Distribute 3 metal running wheels of varying diameters (11.5 cm, 20.5 cm, 28 cm) and 4-5 additional plastic huts/tunnels throughout the space.

- Cover the bin with a micro-isolator filter paper secured with binder clips [11].

B. Animal Housing and Maintenance

- Subjects: House 10-20 mice of the same age, gender, and genetic strain together to foster complex social interactions. Begin EE exposure at weaning (21 days) or as required by the experimental design.

- Daily Checks: Observe animals for health and signs of distress. Administer topical antibiotics for minor wounds and consult veterinary staff for serious conditions.

- Weekly Maintenance:

- Rearrange all enrichment devices to create a novel spatial configuration, a key driver of ongoing adaptation and plasticity.

- Replace water bottles and clean feeding cages.

- Spot-clean the bin as needed [11].

The experimental workflow, from setup to data collection, is outlined below.

For researchers aiming to investigate neural circuit modification through EE, a core set of tools and reagents is required. This toolkit spans from standard housing materials to advanced analytical techniques.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Resource Solutions for EE Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Examples / Models | Function in EE Research |

|---|---|---|

| Housing & Enrichment | Large bin (120x90x76 cm); Igloos with saucer wheels; Plastic tunnels/tubes; Wooden logs; Metal running wheels (various sizes) | Provides the physical framework for EE, enabling sensory, motor, and cognitive stimulation. |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6 mice; 129S6/SvEv mice; Transgenic models of neurological disorders (e.g., Alzheimer's, CP) | Subject for EE interventions. Strain and model choice can significantly impact outcomes and must be carefully considered [13]. |

| Behavioral Analysis | Open field test; Elevated plus maze; Rotarod; Morris water maze; Novel object recognition | Quantifies functional outcomes of EE-induced circuit changes, such as improved learning, memory, and motor coordination. |

| Neural Activity Assays | NEUROeSTIMator computational tool; scRNA-seq; Immunohistochemistry (c-Fos, Arc); Patch-seq | Measures neuronal activation and transcriptomic changes at single-cell resolution, linking EE exposure to circuit-level activity [14]. |

| Pathway Analysis | Antibodies for pCREB, BDNF, TrkB; RNAscope for IEGs; ELISA kits | Validates activation of key molecular pathways (e.g., BDNF-TrkB signaling) implicated in EE-mediated plasticity. |

Environmental enrichment has matured from a simple concept of "improved housing" to a precise, potent, and non-invasive experimental paradigm for driving and studying neural circuit modification. The quantitative data confirms its efficacy in enhancing motor and cognitive outcomes, particularly during critical developmental windows. The detailed protocols provided ensure that this robust phenotype can be reliably reproduced across laboratories, a necessity for rigorous preclinical research. For drug development professionals, EE offers a powerful tool for validating novel targets that modulate neural plasticity. Future research will likely focus on further deconstructing the critical elements of EE, personalizing enrichment protocols based on genetic and neural biomarkers, and integrating EE with other intervention modalities, such as neuromodulation or pharmacological treatments, to achieve synergistic effects for optimizing brain performance and treating circuit-level disorders.

The Role of Affordances in Expanding Behavioral Repertoires

The concept of affordances—originally defined by Gibson as what the environment "offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill"—represents a fundamental mechanism through which organisms perceive and interact with their environments [15]. Within neurobiological frameworks of optimal brain performance, affordances transcend simple stimulus-response associations, emerging as dynamic neural processes that enable rapid adaptation and behavioral repertoire expansion. Contemporary research reveals that affordance processing is not merely a psychological construct but a measurable property of our brains, with specific neural activations reflecting how we can move through different environments without conscious thought [16]. This whitepaper examines the neural mechanisms, experimental approaches, and pharmacological implications of affordance processing, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical foundation for investigating how the brain's perception of action opportunities shapes behavioral flexibility and cognitive performance.

The neurobiological significance of affordances lies in their role as interface mechanisms between environmental structure and organismic capabilities. Recent research has established that certain visual cortex areas become active in ways that cannot be explained solely by visible objects in an image, but rather represent what an observer can do with those objects [16]. This automatic processing of action possibilities occurs even without explicit instruction, suggesting that affordance detection represents a fundamental, hardwired mechanism for efficient environmental interaction. For drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms opens potential pathways for interventions targeting neurological conditions characterized by behavioral inflexibility, such as Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and age-related cognitive decline [17].

Neural Mechanisms of Affordance Processing

Neuroanatomy and Temporal Dynamics of Affordance Perception

Affordance processing involves distributed neural networks that transform object properties into potential action plans. Key regions include the ventral premotor cortex (area F5), intraparietal area AIP, and parietal area V6A, which collectively form a "cortical grasping network" [18]. Neurophysiological studies in macaques reveal distinct temporal dynamics for different affordance types: pragmatic affordances (physical interactions based on object size/shape) elicit sustained neuronal activation in premotor cortex, while semantic affordances (behavioral relevance based on object meaning) trigger transient, phasic responses with shorter latency [18]. This differential processing suggests separate yet interactive neural pathways for physical and conceptual action possibilities.

Table 1: Neural Correlates of Affordance Processing

| Brain Region | Function in Affordance Processing | Activation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral Premotor Cortex (F5) | Transforms object properties into motor plans | Sustained for pragmatic affordances; Phasic for semantic affordances |

| Parietal Area AIP | Processes visual object features for grasping | Object-selective responses during visual presentation |

| Visual Cortex | Represents action possibilities beyond visual features | Automatic activation independent of explicit task demands |

| Parahippocampal Region | Processes architectural affordances | Alpha-band desynchronization before environment interaction |

| Posterior Cingulate Cortex | Integrates affordances during interaction | Dynamic reflection of affordable behavior during task execution |

Human neuroimaging studies corroborate these findings, revealing that when individuals view environmental scenes, specific visual cortex activations reflect potential actions (walking, cycling, driving, swimming) independent of the visual content itself [16]. This neural representation of action possibilities occurs automatically, without conscious deliberation, suggesting that our brains continuously maintain a sensorimotor map of potential interactions with our surroundings. The alpha-band oscillations in parieto-occipital and medio-temporal regions systematically covary with architectural affordances, with event-related desynchronization (ERD) indicating reduced inhibition in sensory and motor areas when assessing action opportunities [19].

Dopaminergic Regulation of Affordance Salience

Dopaminergic systems play a crucial role in modulating the salience and precision of affordance perception. Rather than merely encoding reward prediction errors, dopamine appears to control the precision or salience of cues that engender action, effectively balancing bottom-up sensory information and top-down prior beliefs [17]. This Bayes-optimal perception framework positions dopamine as a key regulator of uncertainty in hierarchical inferences about affordances. Dopamine depletion models demonstrate how disrupted salience assignment leads to perseverative behaviors and set-switching deficits characteristic of Parkinson's disease [17].

The dopaminergic mechanism operates primarily through modulation of postsynaptic gain in cortical and subcortical structures concerned with predicting choices and motor responses. By enhancing the precision of prediction errors, dopamine confers salience on particular sensorimotor representations, effectively selecting which affordances enter conscious awareness and potentially guide action selection [17]. This process aligns with the affordance competition hypothesis, where multiple potential actions compete for execution, with dopaminergic signaling biasing this competition toward contextually appropriate selections. For pharmaceutical researchers, this suggests that dopaminergic therapies should target precision modulation rather than simple reward pathways.

Experimental Paradigms and Methodologies

Standardized Affordance Assessment Protocols

The Affordances Task has emerged as a standardized tool for assessing cognition and visuomotor functioning, with recent methodological advances establishing its test-retest reliability [20]. In the classic paradigm, participants classify images of manipulable objects (e.g., cups with prominent handles) according to a specific rule while suppressing irrelevant motor responses automatically afforded by the objects. The resulting cognitive conflicts manifest at both task and response levels, allowing researchers to quantify how automatically perceived affordances influence goal-directed behavior.

Table 2: Key Experimental Paradigms in Affordance Research

| Paradigm | Procedure | Measured Variables | Neural Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Affordances Task | Object classification while suppressing automatic grasping responses | Response time differences between congruent/incongruent trials; Error rates | fMRI/EEG activation in premotor and parietal regions |

| Mobile Brain/Body Imaging (MoBI) | Motor priming in virtual environments with varying architectural affordances | Event-related desynchronization in alpha band; Behavioral measures of transition | Source-level time-frequency analysis of EEG data |

| Go/No-go Visuomotor Tasks | Object presentation followed by grasp/refrain decisions based on auditory cue | Single-neuron responses in premotor cortex; Population-level dynamics | Ventral premotor cortex activation patterns |

| Bayesian Generative Modeling | Hierarchical models of individual differences in affordance perception | Test-retest reliability; Individual performance distributions | Model-based estimates of neural precision weighting |

Recent methodological innovations address the reliability paradox, wherein behavioral tasks producing robust group-level effects often yield low test-retest reliability when assessed with traditional correlation methods [20]. Hierarchical Bayesian models provide a solution by generating participant-specific distributions that account for trial-level variance, offering more precise reliability estimates than conventional summary statistics. This approach has demonstrated good test-retest reliability for the Affordances Task, supporting its utility for measuring individual differences in cognitive and visuomotor functioning [20].

Mobile Brain/Body Imaging in Virtual Environments

The Mobile Brain/Body Imaging (MoBI) approach integrates virtual reality with electrophysiological monitoring to investigate how architectural affordances influence sensorimotor dynamics in ecologically valid contexts [19]. In a representative paradigm, participants navigate virtual rooms connected by transitions of varying width (impassable to easily passable) while EEG recordings capture neural dynamics during approach and transition phases. This methodology reveals how sensorimotor oscillations covary with architectural affordances, with alpha-band desynchronization in occipital and parahippocampal regions predicting interaction possibilities before actual movement execution [19].

The experimental workflow for MoBI studies typically follows an S1-S2 paradigm, where a preparatory stimulus reveals perceptual information about upcoming environmental interactions, followed by an imperative stimulus instructing whether to execute the action. Analysis focuses on event-related desynchronization in the alpha band between S1 and S2, particularly in parieto-occipital regions, which reflects the gating of sensory information and preparation of motor responses based on perceived affordances [19].

Diagram 1: Mobile Brain/Body Imaging Experimental Workflow for Affordance Research

The Dynamic Affordance Trajectory Framework

Multiscalar Integration of Affordance Processing

The Dynamic Affordance Trajectory Framework (DATF) provides a comprehensive model for understanding how affordances shape behavior and identity across multiple temporal scales [21]. This framework integrates short-term perception-action cycles (micro), medium-term adaptive processes (meso), and long-term sociocultural influences (macro), emphasizing how cognitive agency extends beyond individual neural processes to encompass distributed environmental relationships. The DATF conceptualizes affordances not as static properties but as dynamically evolving opportunities for action that unfold over time, influenced by both individual development and environmental constraints [21].

At the micro scale, affordances emerge through real-time coupling between an animal's sensorimotor abilities and its niche, with affordances and abilities causally interacting in a nonlinear fashion [21]. Meso-scale processes involve the development of affective niches—specific environmental interactions that enable particular emotional states—through which individuals actively regulate their experiences. At the macro scale, sociocultural practices establish shared routines and patterns that shape affordance perception across developmental timespans, creating what the DATF terms ontogenetic niche trajectories [21].

Applications for Behavioral Repertoire Expansion

The DATF has significant implications for designing interventions to expand behavioral repertoires in clinical populations. By recognizing that identity and behavior emerge from dynamic agent-environment interactions across temporal scales, therapeutic approaches can target specific levels of affordance processing:

- Micro-scale interventions might focus on real-time perception-action coupling through sensorimotor integration therapies

- Meso-scale approaches could emphasize the development of adaptive affective niches that support positive emotional regulation

- Macro-scale strategies would address sociocultural influences on affordance perception through community-based rehabilitation programs

This multiscalar approach aligns with emerging evidence that effective behavioral interventions must address neural, individual, and social dimensions simultaneously to produce lasting changes in behavioral repertoires.

Research Reagent Solutions for Affordance Neuroscience

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Affordance Neuroscience

| Research Tool | Specifications | Experimental Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | 64-256 channels; Mobile capabilities; Integrated with motion capture | Recording event-related potentials and oscillatory dynamics during naturalistic behavior | Measuring alpha-band ERD during environmental navigation [19] |

| Virtual Reality Platforms | Head-mounted displays; Room-scale tracking; Custom environment design | Presenting controlled architectural affordances in immersive contexts | Testing transition affordances with varying door widths [19] |

| Bayesian Modeling Software | Hierarchical Bayesian frameworks; Generative modeling capabilities | Estimating test-retest reliability; Modeling individual differences | Assessing reliability of affordances task performance [20] |

| Single-Neuron Recording Arrays | Multi-electrode arrays; Chronic implantation in premotor cortex | Measuring temporal dynamics of pragmatic vs. semantic affordances | Identifying sustained vs. phasic responses in area F5 [18] |

| fMRI-Compatible Stimulus Presentation | High-resolution displays; Response recording systems | Localizing neural correlates of affordance perception | Identifying visual cortex activation to action possibilities [16] |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Development and Neurological Therapeutics

The neurobiological understanding of affordances presents novel targets for pharmaceutical interventions aimed at expanding behavioral repertoires in neurological and psychiatric conditions. Dopaminergic medications for Parkinson's disease could be refined to specifically enhance the precision of affordance perception, potentially improving motor planning and reducing akinesia [17]. Similarly, treatments for schizophrenia might target aberrant salience assignment to affordances, which could reduce inappropriate behavioral responses to environmental cues.

The role of dopamine in modulating the precision of prediction errors provides a specific mechanism for pharmaceutical manipulation [17]. Rather than broadly enhancing or inhibiting dopaminergic signaling, precision-focused approaches would seek to optimize the uncertainty estimates that govern affordance competition. This suggests that context-dependent dopaminergic modulation—rather than blanket increases or decreases—may produce the most therapeutic benefits for conditions characterized by behavioral inflexibility.

From a developmental perspective, the DATF's concept of ontogenetic niche trajectories suggests that pharmaceutical interventions should be timed to critical periods when specific affordance landscapes are being established [21]. Early interventions that shape how individuals perceive and respond to environmental action possibilities could potentially redirect developmental pathways toward more adaptive behavioral repertoires.

Affordance processing represents a crucial mechanism through which the brain efficiently navigates complex environments by automatically detecting potential actions. The expanding neurobiological understanding of these processes offers promising avenues for enhancing behavioral flexibility in clinical populations and optimizing performance in healthy individuals. Future research should further elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying dopaminergic precision-weighting of affordances, develop more sophisticated computational models of the affordance competition process, and translate laboratory findings into real-world interventions that expand behavioral repertoires across the lifespan.

For pharmaceutical researchers, affordance neuroscience provides a framework for developing precisely targeted therapies that enhance adaptive behavior by optimizing how the brain perceives and selects among potential actions in complex environments. By bridging neural mechanisms, individual behavior, and environmental influences, this approach offers the potential for more effective interventions that address the full complexity of human behavior.

Building Cognitive and Neurogenic Reserve Across the Lifespan

Within neurobiological research on optimal brain performance, the concept of cognitive reserve (CR) is defined as an individual's overall cognitive resources at a given point in time, a level that can change across the life course [22]. It represents the brain's resilience and its ability to withstand age-related changes or neuropathology while maintaining cognitive function. Building this reserve is not a late-life endeavor but a lifelong process, influenced by a dynamic interplay of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, outlining the core mechanisms, quantitative biomarkers, and experimental methodologies for investigating and fostering cognitive and neurogenic reserve across the entire lifespan.

Core Neurobiological Mechanisms of Reserve

The neurobiological substrates of reserve are multifaceted, involving structural, functional, and molecular mechanisms.

Neural Substrates and Lifespan Trajectories

The foundation of cognitive reserve is laid early in life through brain development processes. General Cognitive Ability (GCA) in young adulthood is positively associated with brain volume and cortical surface area, serving as a key index of an individual's initial cognitive reserve [22]. This early reserve has demonstrated a long-lasting impact; higher GCA measured at age 18 is associated with a lower hazard ratio for dementia decades later [22]. From a lifespan perspective, this suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive development during childhood and adolescence, when there is substantial brain development, may be more effective for reducing long-term dementia risk than later-life cognitive training alone [22].

Throughout adulthood, the brain demonstrates functional plasticity through the reorganization of neural networks. Key networks include the Default Mode Network (DMN), the Dorsal and Ventral Attention Networks (DAN/VAN), and the Salience Network (SN). The dynamic interactions between these networks are crucial for efficient attention allocation and cognitive function [23]. Age-related declines in functional connectivity, particularly within the DMN's posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and superior frontal gyri, are well-documented and correlate with cognitive deficits [23]. Separate assessment of negative and positive functional connectivity metrics can enhance sensitivity to these aging effects and clarify mixed findings in the literature [23].

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

At a molecular level, several pathways govern neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, which are fundamental to reserve.

- BDNF-TrkB Signaling: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) signaling through its Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) is a primary regulator of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, and differentiation. It is crucial for learning and memory.

- CREB Activation Pathway: The transcription factor cAMP Response Element-Binding protein (CREB) is activated by various signals, including those from BDNF-TrkB. It induces the expression of genes critical for long-term potentiation (LTP) and neurogenesis.

- Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: This pathway is essential for adult hippocampal neurogenesis, regulating the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells.

- Notch Signaling Pathway: This pathway maintains the neural stem cell pool in the subventricular and subgranular zones, balancing self-renewal and differentiation.

The diagram below illustrates the interplay of these core pathways in mediating neurogenic and cognitive reserve.

Diagram 1: Core signaling pathways underlying neurogenic and cognitive reserve. Key pathways include BDNF-TrkB, Wnt/β-Catenin, and Notch signaling, which converge on gene expression and neurogenesis.

Quantitative Assessment and Biomarkers

Objective measurement of reserve relies on a multi-modal approach, integrating cognitive, neuroimaging, and molecular data.

Cognitive and Behavioral Metrics

Longitudinal studies are essential for quantifying the protective effect of reserve proxies. A 52-year survival analysis found that a higher young adult General Cognitive Ability (GCA) was associated with a significantly lower dementia risk (Hazard Ratio = 0.865), whereas education and occupational complexity did not contribute significantly after accounting for GCA [22].

Table 1: Key Cognitive and Neuroimaging Biomarkers of Reserve

| Domain | Biomarker | Measurement Technique | Association with Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Cognition | Young Adult General Cognitive Ability (GCA) | Standardized cognitive batteries (e.g., Swedish Enlistment Battery) [22] | Hazard Ratio = 0.865 for dementia per unit increase [22] |

| Functional Connectivity | Connectivity Strength Index (CSI) | Quantitative Data-Driven Analysis (QDA) of R-fMRI; convolution of cross-correlation histogram [23] | Declines with age in DMN (superior/middle frontal gyri, PCC); sensitive to aging effects [23] |

| Functional Connectivity | Connectivity Density Index (CDI) | Quantitative Data-Driven Analysis (QDA) of R-fMRI; convolution of cross-correlation histogram [23] | Provides density metric of local voxel connectivity with the rest of the brain [23] |

| Network Integrity | Default Mode Network (DMN) Connectivity | Resting-state fMRI (ICA or QDA) [23] | Age-related declines in posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and medial prefrontal cortex correlate with cognitive deficit [23] |

| Network Integrity | Sensorimotor Network Connectivity | Resting-state fMRI (ICA or QDA) [23] | Can show enhanced negative connectivity strength with adult age [23] |

Advanced Neuroimaging and Data Analysis

Moving beyond traditional region-of-interest (ROI) and independent component analysis (ICA), multi-table methods like covSTATIS are advancing network neuroscience. This method is designed for analyzing multiple correlation or covariance matrices, such as functional connectivity matrices from different individuals or sessions [24]. It computes a similarity matrix (RV matrix) from all input matrices, derives weights for each, and generates a compromise matrix that best represents the group-level connectivity pattern [24]. This allows for the simultaneous extraction of global factor scores (group-level connectivity patterns) and partial factor scores (individual-specific expressions), providing a powerful, unsupervised framework for identifying group-level patterns and individual heterogeneity in network configuration [24].

The workflow for this analytical approach is detailed in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: The covSTATIS analytical workflow for multi-table functional connectivity analysis. The process integrates multiple connectivity matrices to derive a consensus and individual deviations.

Experimental Protocols for Reserve Research

This section details methodologies for key experiments investigating interventions to build cognitive reserve.

Protocol: Precision Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation

This protocol outlines a method for enhancing working memory using high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) with real-time fMRI feedback, as demonstrated in a 2025 study [25].

- Objective: To investigate the causal effect of precision-targeted neurostimulation on working memory performance and neural connectivity.

- Materials:

- HD-tDCS system with multi-electrode setup.

- 3T MRI scanner with capabilities for real-time fMRI processing.

- Working memory task (e.g., N-back task) programmed in presentation software (e.g., PsychoPy, E-Prime).

- Electrode gel, skin preparation kit, measuring tape.

- Procedure:

- Screening & Baseline: Obtain informed consent. Assess participants' eligibility. Administer a baseline working memory task inside the MRI scanner to identify individual-specific neural networks activated during the task.

- Individualized Target Definition: Use real-time fMRI data acquired during the baseline task to localize the peak activation within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) or other target networks for each participant.

- Stimulation Setup: Position the HD-tDCS electrodes on the scalp based on computational modeling to maximize current delivery to the individualized target. Ensure electrode-skin impedance is below 10 kΩ.

- Intervention:

- Active Group: Deliver HD-tDCS (e.g., 2 mA for 20-30 minutes) while the participant performs the working memory task. Use real-time fMRI to monitor and slightly adjust stimulation parameters to maintain target engagement.

- Sham Group: Follow the same procedure but deliver a brief ramp-up/ramp-down current with no sustained stimulation.

- Post-Intervention Assessment: Immediately after stimulation, and at follow-up intervals (e.g., 1 week, 2 weeks), re-administer the working memory task both inside and outside the scanner to assess immediate and lasting effects on performance and functional connectivity.

- Data Analysis: Compare pre- to post-intervention changes in task accuracy, reaction time, and functional connectivity (e.g., using CSI or network-based statistics) between active and sham groups.

Protocol: Targeted Memory Reactivation During Sleep

This protocol describes a method to enhance declarative memory consolidation using targeted memory reactivation (TMR) in conjunction with sleep EEG monitoring [25].

- Objective: To strengthen specific memories by re-presenting associated sensory cues during slow-wave sleep.

- Materials:

- Consumer-grade EEG headband or full polysomnography system capable of identifying sleep stages.

- Smartphone or computer with a dedicated TMR application for cue delivery.

- Audio recording and presentation equipment.

- Procedure:

- Learning Phase (Evening): Participants learn and encode novel information (e.g., word pairs, object locations). During learning, each specific memory item is paired with a unique, unobtrusive auditory cue (e.g., a specific sound or tone).

- Cueing Phase (During Sleep): Participants sleep in the lab or at home with the EEG device.

- The EEG data is streamed in real-time to detect the onset of slow-wave sleep (N3).

- During stable periods of slow-wave sleep, the TMR system delivers the auditory cues associated with a randomly selected half of the learned material. The other half serves as an within-subject control.

- Cues are presented softly to avoid causing arousal.

- Recall Phase (Morning): After awakening, participants are tested on their recall for all the learned information, both cued and un-cued.

- Data Analysis: Compare recall accuracy for cued versus un-cued memories. A successful TMR effect is demonstrated by significantly better recall for the cued items (e.g., a 35% improvement as reported in recent studies [25]).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Cognitive Reserve Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| HD-tDCS System | Multi-channel, MRI-compatible system | Precise neuromodulation of cortical targets with real-time fMRI integration for causal experiments [25]. |

| EEG Sleep Monitor | Consumer-grade headband or research-grade polysomnography | Monitoring sleep architecture and identifying slow-wave sleep stages for targeted memory reactivation protocols [25]. |

| Functional MRI Scanner | 3T or higher, with real-time processing capability | Assessing functional connectivity (e.g., DMN integrity) and providing feedback for precision stimulation [25] [23]. |

| Cognitive Assessment Battery | Tests for GCA, working memory, episodic memory | Quantifying baseline cognitive ability and tracking intervention-induced changes in specific cognitive domains [22]. |

| Analysis Software for covSTATIS | Custom code (e.g., R, Python) as per Baracchini et al., 2024 [24] | Multi-table analysis of functional connectivity matrices to identify group and individual-level network patterns [24]. |

| Graphic Protocol Tool | BioRender [26] | Creating clear, standardized, and visually accessible experimental protocols to ensure reproducibility and streamline knowledge transfer within research teams [26]. |

Building cognitive and neurogenic reserve is a dynamic process that requires a multi-faceted, lifespan-oriented strategy. The evidence indicates that the foundation of reserve is built early in life, with young adult GCA being a powerful predictor of late-life cognitive health [22]. However, the brain's functional plasticity, evident in the reorganization of networks like the DMN and the potential for experience-dependent neurogenesis, provides opportunities for intervention across adulthood [23]. The most promising future direction lies in integrated approaches that synergistically combine behavioral interventions (e.g., precision exercise), technological innovations (e.g., closed-loop neuromodulation), and nutritional strategies, all timed to leverage natural brain rhythms [25]. For researchers and drug developers, this underscores the need to move beyond single-target therapies and instead develop personalized, multi-modal intervention regimens that are calibrated to an individual's genetic profile, baseline cognitive capacity, and specific life stage to optimally build and maintain cognitive reserve from youth through old age.

Emotional Regulation and Resilience as Components of Optimal Function

Emotional regulation and psychological resilience represent critical determinants of optimal brain function, particularly within neurobiological frameworks investigating peak cognitive performance. Emotional regulation refers to the dynamic processes through which individuals influence their emotional experiences and expressions, while psychological resilience constitutes the adaptive capacity to withstand and recover from adversity [27]. These constructs operate synergistically through shared neural circuits, with the prefrontal cortex exerting top-down control over amygdala-mediated emotional responses [28] [27]. Understanding their neurobiological underpinnings provides crucial insights for developing interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive performance and mental wellbeing across diverse populations.

Recent advances in neuroscience have elucidated the intricate relationships between these constructs, revealing them not as isolated psychological phenomena but as deeply interconnected biological processes measurable through electrophysiological correlates, neuroimaging biomarkers, and psychometric assessments [28]. This whitepaper synthesizes current neurobiological evidence, experimental methodologies, and research tools to establish a comprehensive framework for investigating emotional regulation and resilience as fundamental components of optimal brain function.

Theoretical Foundations and Neurobiological Mechanisms

Conceptual Frameworks

The relationship between emotional regulation and resilience is best understood through integrative theoretical models. Gross's Process Model of Emotion Regulation delineates five sequential stages: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation [27]. This framework aligns with the Integrative Affect-Regulation Framework for Resilience, which combines stress-coping and emotion-regulation perspectives by categorizing strategies into situation change, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation [29]. These complementary models establish the mechanistic pathways through which regulatory capacities foster resilient outcomes.

Network analysis reveals that specific components form crucial bridges between these constructs. In adolescent populations, the positive cognition item "Believing that everything has a positive side" demonstrated statistically superior bridge strength, identifying it as the most robust connector between psychological resilience and emotion regulation networks [30]. This cognitive-reappraisal capability represents a shared mechanism that enhances both regulatory capacity and stress adaptation.

Neural Correlates and Electrophysiological Signatures

Table 1: EEG Frequency Bands and Their Associations with Cognitive States and Resilience

| Band Name | Frequency Range (Hz) | Associated Cognitive States | Relationship to Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0-4 | Deepest relaxation, restorative, dreamless sleep | Limited direct evidence |

| Theta | 4-8 | Deep relaxation, deep meditation | Trend-level association (p=0.08) at electrode P4 [28] |

| Alpha | 8-12 | Calm wakefulness, resting state, meditation | Significant relationship with resilience; resilient children show greater left hemisphere alpha activity [28] |

| Beta | 12-30 | Alert, active thinking, focus, attention, anxiety | Limited significant findings with resilience |

| Gamma | 30-200 | Heightened perception, learning, information processing | Equivocal findings; only two studies specifically examined gamma-resilience association [28] |

Neuroimaging evidence consistently identifies the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and amygdala as key regions comprising the "emotion regulation brain circuitries" associated with resilience [28]. These regions facilitate the top-down control essential for adaptive stress responses. The autonomic nervous system, particularly vagus nerve function as described in Polyvagal Theory, further contributes to emotional regulation through social engagement and self-soothing mechanisms [27].

Electroencephalographic (EEG) research reveals that resilient individuals exhibit distinct electrophysiological profiles, with alpha band activity showing the most consistent associations with psychological resilience [28]. Resilient children demonstrate greater left hemisphere alpha activity compared to non-resilient peers, suggesting hemispheric asymmetry in resilience mechanisms [28]. The neurobiological relationship between these constructs can be visualized through the following signaling pathway:

Figure 1: Neurobiological Pathways of Emotion Regulation and Resilience

Quantitative Research Findings

Empirical Evidence from Recent Studies

Table 2: Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Resilience and Emotion Regulation Research

| Study/Measure | Sample Characteristics | Key Quantitative Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Resilience Network Analysis [30] | 2,119 Chinese adolescents (Mean age=12.25±0.45 years) | Females scored lower on psychological resilience dimensions and cognitive reappraisal, but higher on expressive suppression | Bridge strength of positive cognition item statistically superior (p<0.05) |

| Affect Regulation-Based Resilience Scale (ARRS) [29] | Two adult samples (n=424 and n=425) | Significant positive correlations with psychological resilience (r=NA), stress-related growth, cognitive reappraisal, and subjective well-being; negative correlation with depression, anxiety, expressive suppression and stress | p<0.05 for all correlations; satisfactory item performance and good fit for four-factor model |

| EEG and Resilience Association [28] | 7 studies (2019-2025) reviewing EEG and PR | Significant relationship between CDRISC score and alpha coherence in right hemisphere; no significant relationships with beta or gamma coherence | p<0.05 for alpha coherence; non-significant for beta/gamma |

| U.S. POINTER Lifestyle Intervention [31] | Nationwide clinical trial with older adults | Structured lifestyle intervention (38 sessions over 2 years) showed greater cognitive benefits than self-guided intervention | Results held across age, sex, ethnicity, cardiovascular health and APOE e4 genetic risk |

Large-scale studies demonstrate the efficacy of targeted interventions. The U.S. POINTER study revealed that structured lifestyle interventions incorporating physical activity, nutrition, heart health monitoring, and cognitive engagement significantly improve global cognitive function in older adults [31]. Similarly, the Building Resilience through Socioemotional Training (ReSET) intervention for adolescents employs a transdiagnostic approach focusing on emotion processing and social mechanisms implicated in psychopathology [32].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Intervention Protocols

The Building Resilience through Socioemotional Training (ReSET) protocol represents a rigorously designed intervention targeting emotion regulation and resilience mechanisms [32]. This cluster randomised controlled trial employs the following methodology:

- Participants: 540 adolescents aged 12-14 years from schools with higher-than-average incidence of poverty

- Design: Cluster randomised allocation with randomisation at school year level

- Intervention Structure: Weekly sessions over 8-week period, supplemented by two individual sessions

- Control Condition: Passive control group

- Primary Outcomes: Psychopathology symptoms and mental wellbeing assessed pre- and post-intervention, and at 1-year follow-up

- Secondary Outcomes: Task-based assessments of emotion processing, social network data from peer nominations, subjective ratings of social relationships

- Additional Measures: Interoceptive attention and accuracy at baseline, post-intervention and 1-year follow-up