Presence and Immersion in Virtual Neuroscience: A Research Framework for Enhanced Experimental Validity and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of presence and immersion in virtual reality (VR) neuroscience experiments, synthesizing the latest research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Presence and Immersion in Virtual Neuroscience: A Research Framework for Enhanced Experimental Validity and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of presence and immersion in virtual reality (VR) neuroscience experiments, synthesizing the latest research for scientists and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational distinction between technological immersion and the subjective feeling of presence, review advanced methodological applications from empathy induction to procedural training, and address key challenges in measurement and optimization. The article further examines the ecological validity and behavioral realism of VR settings through comparative studies, offering a validated framework for leveraging immersive technologies to improve the predictive power of neuroscientific and clinical research.

Deconstructing the VR Experience: Core Principles of Immersion and Presence

In virtual neuroscience, the precise distinction between immersion and presence is not merely academic; it is a fundamental prerequisite for designing valid and reproducible experiments. Immersion is an objective property of the technology, quantifiable through specifications like field of view, resolution, and tracking accuracy. In contrast, presence is the subjective psychological response—the user's feeling of "being there" in the virtual environment [1]. This dichotomy is critical because the ultimate goal of using Virtual Reality (VR) in neuroscience is to evoke strong, measurable presence to enhance the ecological validity of experimental settings without sacrificing experimental control [2]. The confusion between these terms can lead to flawed study designs where technological capabilities are erroneously equated with user experience, thereby compromising data on neural and cognitive processes. This paper establishes a definitive framework to guide researchers in the rigorous application of VR for studying brain function and behavior.

Theoretical Foundations: Deconstructing the Illusion of Reality

Immersion: The Technological Framework

Immersion refers to the extent to which a VR system can deliver a vivid, encompassing, and interactive simulation that shutters out inputs from the physical world. It is a characteristic of the hardware and software itself.

- Key Technological Dimensions of Immersion:

- Visual Fidelity: Includes display resolution, refresh rate, color depth, and freedom from screen-door effects.

- Auditory Fidelity: The quality of spatial audio that changes dynamically with head movement.

- Tracking Accuracy and Latency: The precision of head and motion tracking and the minimization of lag between user movement and system response.

- Field of View (FOV): A wider FOV more closely mimics human binocular vision, increasing perceptual immersion.

- Haptic Feedback: The provision of tactile sensations that correspond to virtual interactions.

Presence: The Psychological State

Presence, or the "illusion of being there," is the psychological sense of being located in and engaged with the virtual environment, even when one is physically in another location [3] [1]. It is not a direct output of the technology but a mediated human experience. Contemporary research argues that presence is primarily a psychological phenomenon shaped by factors extending beyond mere technological sophistication, including content narrative, user characteristics, socio-cultural contexts, and the alignment between the virtual environment and the user's intentions [3].

Mel Slater's influential work further decomposes presence into two core illusions [1]:

- Place Illusion (PI): The visceral sensation of being in a real place, despite knowing one is not.

- Plausibility Illusion (Psi): The belief that the events occurring in the virtual environment are actually happening, even though they are simulated.

Table 1: Core Illusions of Presence and Their Contributing Factors

| Illusion Type | Definition | Key Design & Psychological Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| Place Illusion | The sensation of being physically located in the virtual environment. [1] | High visual realism, spatial audio, stable tracking, low latency, wide field of view. |

| Plausibility Illusion | The belief that the scenario and events in the VR environment are truly occurring. [1] | Narrative coherence, responsive environment, realistic character behavior, user agency. |

| Illusion of Embodiment | The perception of having a virtual body that is one's own. [1] | Body ownership (e.g., through virtual hands), visuomotor synchrony, proprioceptive alignment. |

The relationship between immersion and presence is not linear but facilitative. Higher immersion typically increases the potential for strong presence, but its actualization depends profoundly on psychological and contextual factors [3] [1]. A compelling narrative in a moderately immersive environment can evoke a stronger sense of presence than a technologically advanced but contextually barren simulation.

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Presence

A multi-modal approach is essential for robustly quantifying presence in neuroscience research, combining subjective self-reports with objective behavioral and physiological measures.

Subjective Self-Report Measures

These are the most direct, though introspective, methods for assessing the subjective feeling of presence.

- The Presence Questionnaire (PQ): Developed by Witmer and Singer, this is a widely used standardized instrument that measures presence across factors like involvement, sensory fidelity, and adaptation/immersion [1].

- The Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) Questionnaire: A shorter questionnaire that focuses specifically on the sense of "being there," the extent to which the VR environment becomes the "reality," and the tendency to forget about the real world [1].

- Post-Experiment Interviews: Qualitative interviews can provide rich, nuanced data about the participant's experience that may not be captured by standardized questionnaires.

Objective and Behavioral Measures

These measures provide indirect, non-intrusive indicators of presence by observing participant behavior.

- Behavioral Realism: Researchers can observe if participants interact with virtual objects as they would with real ones (e.g., ducking from a virtual projectile, showing startle responses) [1].

- Postural Sway: A participant experiencing strong presence may exhibit postural adjustments in response to virtual slopes or movements.

- Break in Presence (BIP) Detection: A BIP occurs when an external stimulus or system error (e.g., a tracking glitch) shatters the sense of presence. The frequency and nature of BIPs can be a powerful inverse metric for presence [4].

Physiological Correlates

Physiological measures offer continuous, unbiased data that can correlate with the intensity of the presence experience.

- Skin Conductance (SC) / Galvanic Skin Response (GSR): Measures electrodermal activity, which is linked to emotional arousal. Studies have shown a direct correlation between perspiration and high levels of scenario and body realism, indicating its utility as a marker for certain dimensions of presence [4].

- Heart Rate (HR) and Heart Rate Variability (HRV): Can indicate arousal and cognitive load. While one study found HR was not significantly affected by breaks in illusion [4], other research has used it as an indicator of emotional engagement in stressful or exciting virtual scenarios.

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Brain activity patterns, particularly in frontal and parietal regions, have been associated with states of presence and immersion, offering a direct neural correlate.

Table 2: Multi-Modal Matrix for Measuring Presence in Experimental Protocols

| Measure Type | Specific Tool/Metric | Primary Variable Measured | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective | Presence Questionnaire (PQ) [1] | Self-reported sense of presence | Validated, direct insight | Prone to bias, post-hoc |

| Subjective | Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) [1] | Sense of "being there" & dominance of VR | Short, easy to administer | Limited dimensions |

| Behavioral | Behavioral Realism Observation | Naturalistic reactions to virtual stimuli | Objective, indirect | Requires coding, can be ambiguous |

| Behavioral | Break in Presence (BIP) Logging [4] | Resilience of the presence illusion | Objective, real-time | Requires a trigger or error to be observed |

| Physiological | Skin Conductance (SC/GSR) [4] | Arousal related to realism & engagement | Continuous, objective | Can be influenced by non-VR factors |

| Physiological | Heart Rate (HR)/HRV | Cognitive & emotional load | Continuous, objective | Less specific to presence |

| Physiological | Electroencephalography (EEG) | Neural correlates of presence | Direct brain measure | Complex to set up and analyze |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents for Virtual Neuroscience Research

For neuroscientists, a virtual experiment is an apparatus composed of both digital and physical "reagents." The selection of these components directly impacts the immersion and, consequently, the potential for evoking presence.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for VR-Based Neuroscience

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Virtual Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Meta Quest 3/Pro, HTC Vive, Apple Vision Pro, PlayStation VR [5] [6] | Provides the immersive technological framework. Choice determines FOV, resolution, tracking type, and level of mobility. |

| Software Development Engines | Unity, Unreal Engine [5] [6] | The core software for building, rendering, and running the 3D virtual environment and its logic. |

| 3D Modeling & Animation Software | Maya, 3DS Max, ZBrush [5] | Used to create the static and animated 3D assets (rooms, objects, avatars) that populate the virtual world. |

| Spatial Audio SDKs | Oculus Audio SDK, Microsoft Spatial Sound | Creates realistic soundscapes that are crucial for auditory cues and enhancing place illusion. |

| Physiological Data Acquisition Systems | Biopac MP160, ADInstruments PowerLab, Shimmer GSR+ | Hardware and software for synchronously recording physiological data (SC, HR, EEG) with in-VR events. |

| Presence Assessment Kits | Standardized PQ & SUS questionnaires; BIP coding protocols | The validated tools for quantitatively and qualitatively measuring the primary outcome of presence. |

Application in Neuroscience: Enhancing Ecological Validity and Experimental Control

The primary value of the immersion-presence framework for neuroscience lies in resolving the long-standing tension between ecological validity and experimental control [2]. Traditional neuropsychological assessments (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Stroop Test) are highly controlled but often lack verisimilitude—they do not resemble the multi-step, dynamic challenges of real-world functioning [2]. VR solves this by creating simulated environments that are both controlled and contextually embedded.

For example, a VR-based "multiple errands task" can be used to assess executive functions in patients with frontal lobe lesions within a realistic but perfectly standardized virtual city, overcoming the practical and logistical limitations of administering the real-world test [2]. The effectiveness of such a paradigm, however, hinges on the participant experiencing a sufficient degree of presence. Without presence, their behavior may not translate to real-world deficits, as they are not emotionally or cognitively engaged. Therefore, a key application is in the design of function-led neuropsychological tests that proceed from observable everyday behaviors backward to their underlying neural mechanisms [2].

Furthermore, the ability to systematically induce "Breaks in Presence" by manipulating specific VR cues (e.g., social interaction, body representation, scenario realism) provides a powerful experimental paradigm. A 2025 study demonstrated that breaking different facets of presence (social, self, physical) led to distinct behavioral and physiological outcomes, such as increased physical effort under low body representation and lower skin conductance with broken social presence [4]. This level of precise manipulation allows neuroscientists to isolate and study the neural substrates of specific components of conscious experience in ways that are impossible in the unpredictable real world.

A rigorous and dissociated framework for immersion and presence is non-negotiable for the advancement of virtual neuroscience. Immersion defines the bounds of the experimental apparatus, while presence is a key dependent variable—a marker of the paradigm's success in engaging the brain systems under investigation. By meticulously selecting technological reagents to achieve target levels of immersion, and by employing a multi-modal protocol to quantify the resulting presence, researchers can reliably create virtual experiments that are both scientifically controlled and deeply human-relevant. This framework empowers the field to move beyond mere media comparisons and toward a mature science of how the brain constructs reality, using VR as its ultimate controlled illusion.

In the realm of virtual neuroscience, the psychological experience of "being there," or presence, is not a mere byproduct of putting on a headset. It is a complex neurocognitive phenomenon that is central to the efficacy of virtual reality (VR) applications in research and therapy [3]. The sense of presence is the foundational mechanism that allows virtual environments to elicit realistic, ecologically valid behavioral, emotional, and physiological responses, making it indispensable for experimental paradigms and clinical interventions [7] [8].

This whitepaper examines the three primary technical and perceptual drivers of this phenomenon: vividness, interactivity, and user control. For neuroscientists and drug development professionals, a rigorous understanding of these drivers is critical. It enables the design of more effective virtual experiments for studying brain function and behavior, and it supports the creation of robust virtual patient models and molecular visualization tools that can accelerate pharmaceutical development [9] [10]. A sophisticated understanding of presence moves beyond a purely technological focus, recognizing that it is a psychological construct shaped by the coherence between environmental features and a user's expectations and intentional actions [3].

Defining Immersion and Presence: A Neuroscientific Perspective

In virtual neuroscience, it is crucial to distinguish between the concepts of immersion and presence. Immersion is an objective description of the technology's capabilities. It refers to the extent to which a VR system can present a vivid, multi-sensory, and contiguous environment while shutting out the physical world [11] [12]. It is a property of the system itself.

Presence, on the other hand, is the subjective psychological response of the user to the immersive system. It is the illusion of being in the virtual environment, a feeling of "being there" that the brain generates [3] [13]. From a neuroscientific standpoint, this can be understood through the theory of embodied simulations and predictive coding [3]. The brain is constantly generating an internal model of the body and its surroundings to predict sensory input. VR technology, through its high-fidelity feedback, provides sensory data that closely matches the brain's predictions, thereby minimizing prediction error and "tricking" the brain into accepting the virtual environment as real [3].

This illusion is so powerful that it can override our normal sense of embodiment, making us feel as though we genuinely inhabit the virtual space and body. This has profound implications for virtual neuroscience experiments, as it allows researchers to use VR to study neural, physiological, and cognitive bases of human behavior with high ecological validity [7].

The Core Drivers of Immersion

Vividness: Multi-Sensory Fidelity

Vividness refers to the richness and completeness of the sensory information presented by a mediated environment [12]. It is a function of both the breadth (number of senses engaged) and depth (resolution and quality) of the sensory data.

- Technological Foundations: Vividness is achieved through hardware such as head-mounted displays (HMDs) with high-resolution, wide-field-of-view screens and stereo headphones [8]. Advanced systems may also incorporate haptic feedback devices to engage the sense of touch [8].

- Neuroscientific Impact: The brain's predictive coding model is highly dependent on the quality of sensory input. Higher graphical fidelity, spatial audio, and multi-sensory congruence provide a more coherent set of signals, reducing the prediction errors that would break the sense of presence [3]. Vividness is foundational for creating realistic virtual environments for cognitive and affective neuroscience studies [7].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Vividness in VR Experiments

| Research Reagent / Technology | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Provides the visual foundation of the VE with high pixel density and wide field of view to reduce the "screen door" effect. |

| Stereo Headphones / Spatial Audio System | Delivers realistic, 3D-dimensional sound that corresponds to virtual objects and events, enhancing spatial awareness. |

| Haptic Feedback Devices (e.g., data gloves) | Provides tactile and force feedback to simulate the sense of touch, crucial for object manipulation and embodiment. |

| Eye-Tracking System (integrated in HMD) | Measures pupillary response, gaze direction, and blink rate as physiological correlates of cognitive load and emotional response. |

| Olfactory Displays | Releases specific scents to engage the olfactory system, further closing the multi-sensory loop and enhancing realism. |

Interactivity: The Dialogue with the Virtual Environment

Interactivity is the degree to which users can influence the form or content of the virtual environment in real time. It is the extent to which the VR system allows users to manipulate and alter their environment, creating a dynamic two-way interaction [12].

- Technological Foundations: This is enabled by motion-tracking systems (e.g., inside-out tracking, lighthouse systems) that monitor the user's head and body movements [8]. The system must then update the sensory display (visual, auditory, haptic) in real-time to reflect the user's actions, maintaining the perceptual-motor contingency.

- Neuroscientific Impact: Interactivity is the core of agency, the feeling of controlling one's own actions. From a predictive coding perspective, when a user performs an action (e.g., reaching for a virtual object) and the VR system provides the predicted sensory feedback (e.g., the object moving), it reinforces the brain's internal model and strengthens presence [3]. In therapeutic contexts like VRET, this sense of control can enhance a patient's self-efficacy [8].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence on the Impact of Immersion Drivers

| Study Focus | Experimental Protocol / Methodology | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Immersion & Prosocial Behavior [13] | 244 participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions with varying immersion levels: 1) High (Immersive VR HMD), 2) Moderate (360° video on HMD), 3) Low (360° video on desktop). Measured presence, psychological distance, empathy, and prosocial intentions. | - Immersion was positively correlated with physical presence (r = N/A, p < .001). - Physical presence was negatively correlated with perceived spatial distance (r = -0.29, p < .001). - A serial mediation path (Immersion → Physical Presence → Spatial Distance → Empathy → Prosocial Behavior) was supported. |

| VR for Design Reviews [12] | Comparative studies of design reviews conducted in Immersive VR (IVR) versus non-immersive (desktop) environments. Metrics included design understanding, team communication, and outcomes (issues identified). | - Team Communication: IVR resulted in more levelled verbal exchanges among team members compared to non-immersive settings [12]. - Design Understanding: Contradictory evidence; some studies report positive [11] [9] [3] and others negative [12] [7] effects. - Outcomes: Similarly conflicting findings, with evidence for both positive [13] [14] and negative [12] [11] [9] effects on issue identification. |

| Content vs. Technology [3] | Comparison of presence in a VR job interview simulation versus a real-world simulation without rich contextual cues. | - Self-reported presence and anxiety were significantly higher in the VR condition than in the reduced-cue real-world simulation. |

User Control: Agency and Configurability

User control refers to the user's ability to modify their viewpoint and the sequence of interactions, as well as to configure aspects of the environment itself. It encompasses both motor control (the fluidity of navigation) and modulatory control (the ability to influence the environment's state) [8].

- Technological Foundations: This involves low-latency tracking and rendering to ensure user movements are translated instantly into the virtual world. It also includes software features that allow users to pause, reset, or adjust the complexity of the simulation.

- Neuroscientific and Therapeutic Impact: Control is a critical factor for both safety and efficacy. In VR exposure therapy (VRET), the patient's ability to terminate the experience at any moment provides a crucial sense of safety, which can increase engagement and reduce dropout rates [8]. For a virtual neuroscience experiment, allowing users to control the pace of a task can reduce confounding effects of anxiety and stress.

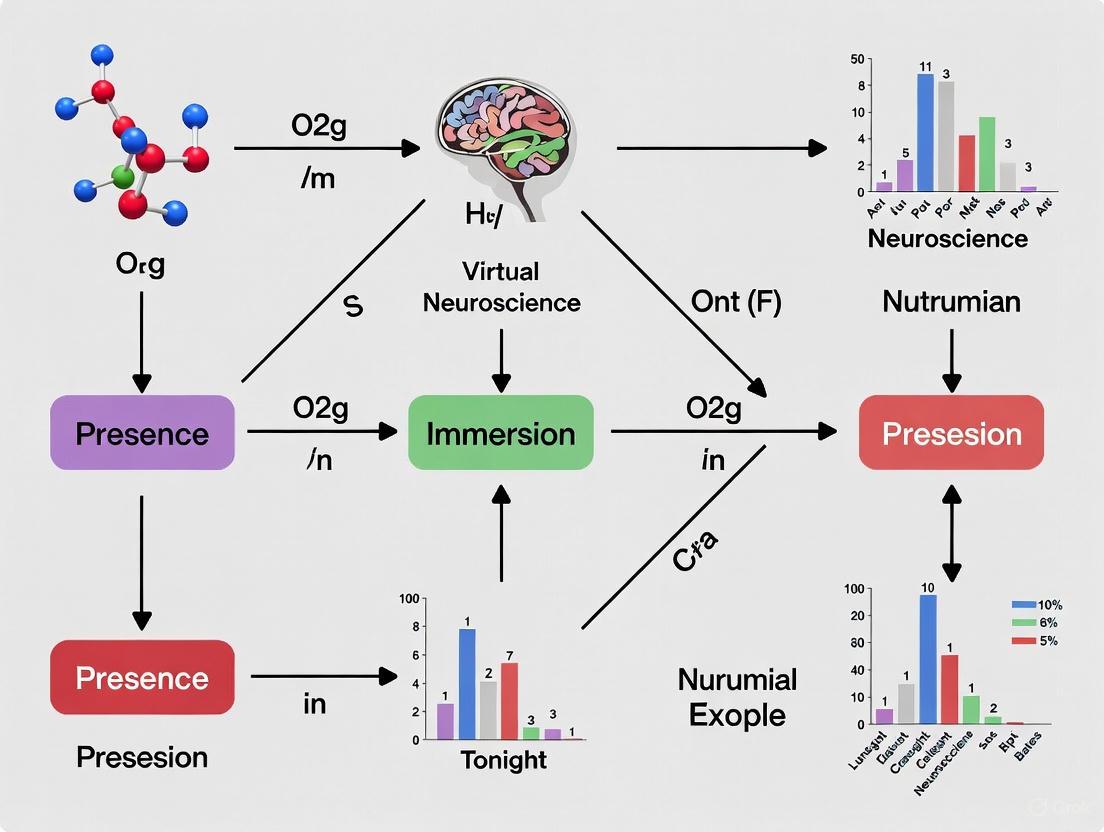

Diagram 1: The neuroscience of presence via predictive coding. The brain accepts the virtual environment as real when sensory input from the VR system closely matches its internal model's predictions, minimizing prediction error.

Advanced Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Development

The precise engineering of presence through vividness, interactivity, and user control is unlocking novel methodologies in research and industry.

Virtual Patients in Clinical Trials

A primary application in drug development is the creation of virtual patient cohorts. These are computer-generated simulations that mimic the clinical characteristics of real patients, allowing for simulated clinical trials without initial human testing [9]. This is particularly valuable for rare diseases where patient recruitment is challenging.

- Methodologies for Creation: Several techniques are employed, each with strengths and weaknesses.

- Agent-Based Modeling (ABM): Simulates individual patient interactions; useful for complex behaviors like immune responses and tumor progression [9].

- AI and Machine Learning: Analyzes large real-world datasets to identify patterns and generate synthetic virtual patients, useful for augmenting small sample sizes [9].

- Digital Twins: Virtual replicas of real patients that are continuously updated with new clinical data, allowing for real-time simulation of interventions [9].

- Biosimulation/Statistical Methods: Uses mathematical models (e.g., Monte Carlo simulations, regression analysis) to extrapolate virtual patient data from existing datasets [9].

Table 3: Methodologies for Generating Virtual Patient Cohorts

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) | Models individual patient interactions and complex behaviors. Applied in oncology for predicting treatment efficacy. | Requires significant computational resources; limited scalability for very large populations. |

| AI & Machine Learning | Analyzes large datasets for patterns; enhances simulation accuracy; facilitates synthetic datasets for rare diseases. | High computational demand; "black box" problem reduces interpretability; risks of bias in training data. |

| Digital Twins | Enables real-time simulations and updates based on live clinical data; high temporal resolution for testing interventions. | High dependency on high-quality, real-time data; expensive and computationally intensive to maintain. |

| Biosimulation/Statistical Methods | Uses established mathematical models; cost-effective for modeling diverse clinical scenarios with smaller datasets. | Limited by model assumptions and accuracy; may oversimplify complex biological systems. |

Molecular Visualization and Drug Design

In structure-based drug design (SBDD), VR provides an immersive 4D visualization of molecular structures. Researchers can intuitively explore and manipulate protein-ligand complexes in real-time, going beyond 2D screens to understand molecular interactions [10]. This immersive visualization is seen as a promising complement to the expanding suite of AI tools in pharmaceutical research, though challenges remain in workflow integration and hardware ergonomics [10].

Virtual Reality in Mental Health

VR has emerged as a revolutionary tool in mental health, particularly through Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET). It allows patients with phobias, PTSD, or anxiety disorders to be gradually exposed to feared stimuli in a safe, controlled, and confidential setting [8]. The effectiveness of VRET is directly tied to the patient's sense of presence—the more vivid and interactive the environment, the more genuine the emotional and physiological response, leading to better therapeutic outcomes [3] [8].

For researchers in virtual neuroscience and professionals in drug development, the drivers of immersion—vividness, interactivity, and user control—are not merely technical specifications but fundamental parameters for experimental and therapeutic efficacy. A deep understanding of these drivers, grounded in neuroscientific principles like predictive coding, allows for the design of virtual experiences that robustly generate presence.

This capability is transforming methodologies, from the use of virtual patients to simulate clinical trials and de-risk drug development, to the creation of immersive molecular visualization tools and highly effective therapeutic interventions like VRET. As the technology continues to advance, a continued focus on the psychological and neuroscientific underpinnings of presence will be essential to fully realize the potential of immersive technologies in understanding the brain and developing new treatments.

The study of presence—the subjective experience of "being there" in a virtual environment—represents a central challenge and opportunity in contemporary virtual neuroscience research. This experience is not merely a perceptual illusion but a complex neurocognitive phenomenon rooted in the brain's fundamental predictive operations. Within the context of virtual reality (VR) experiments, presence arises from the integration of sensory fidelity, motor agency, and embodied prediction—the process by which the brain generates models of the world to anticipate the sensory consequences of actions [15]. The concept of the "predictive brain" has emerged as a pivotal framework in cognitive neuroscience, emphasizing that neural processing is not primarily reactive but proactively oriented toward future states [16]. This framework provides the theoretical foundation for understanding how engineered virtual environments can elicit robust feelings of immersion and presence, with significant implications for experimental design in neuroscience and therapeutic development.

The historical understanding of predictive processing originates from early investigations in both perceptual and motor domains. Notably, early 20th-century work on efference copy and corollary discharge established that motor commands directly influence sensory processing, forming the basis of what are now known as forward models in motor control and other cognitive domains [16]. Contemporary research has expanded these ideas, suggesting that predictive processing represents a fundamental principle of neural computation, where prediction errors—the discrepancies between anticipated and actual sensory input—drive neural adaptation, cognitive updating, and behavior [16]. In virtual environments, this mechanism is paramount: the brain continuously compares its embodied predictions against the incoming stream of multisensory VR stimuli, and minimal prediction errors reinforce the sense that the virtual body is one's own, thereby enhancing presence.

Theoretical Frameworks: Predictive Processing and Embodiment

The Predictive Brain Hypothesis

The predictive brain concept posits that the brain is essentially a hypothesis-testing engine that uses internal models to infer the causes of sensory inputs and predict future states [16]. This view represents a paradigm shift from traditional serial processing models to a framework emphasizing recurrent neural processing and top-down Bayesian inference. The brain maintains generative models that simulate the body in its environment, enabling constant comparison between predicted and actual sensory feedback [16]. In the context of VR, this mechanism is harnessed to create a compelling sense of presence; when the virtual environment accurately predicts the user's actions (e.g., hand movements resulting in corresponding virtual hand movements with appropriate tactile and visual feedback), the internal model incorporates the virtual body, and presence is sustained.

This predictive framework is formally described by the comparator model (also known as central monitoring theory), which is crucial for understanding the sense of agency in virtual embodiments [17]. As shown in Figure 1, an action begins with an intention, leading to a prediction of the sensory consequences of the motor command. When the actual sensory feedback from the VR system matches this prediction, the sense of agency—the feeling of being the cause of one's actions—is strengthened [17]. This cycle of prediction and error minimization is fundamental to creating seamless virtual interactions where the technology becomes "invisible" to the user, allowing full cognitive and emotional engagement with the virtual scenario.

The Sense of Embodiment and Its Components

In virtual reality research, the sense of embodiment (SoE) is defined as the "ensemble of sensations that arise in conjunction with being inside, having, and controlling a body" [17]. This construct is conceptualized as comprising three distinct but interrelated sub-components:

- Sense of Self-Location (SoSL): The spatial experience of being located inside a body, typically within a specific volume of space [17]. In VR, this involves perceiving oneself as inhabiting the virtual body from a first-person perspective.

- Sense of Body Ownership (SoBO): The feeling that a body (or a part of it) belongs to oneself, serving as the source of one's sensations [17]. This can be extended to virtual bodies through synchronized visuomotor correlations.

- Sense of Agency (SoA): The experience of controlling one's own body movements and, through them, events in the external world [17]. As previously mentioned, this arises from the match between predicted and actual sensory consequences of actions.

The relationship between these components is complex and hierarchical. While they can be dissociated under certain experimental conditions (e.g., ownership without agency), they typically function synergistically to produce a unified experience of embodiment [17]. Research suggests that the sense of agency may play a particularly foundational role, as the successful prediction of action outcomes reinforces both ownership and self-location.

Figure 1: The Comparator Model of Sense of Agency. This model illustrates how the brain generates predictions about sensory outcomes and compares them with actual feedback to attribute agency. Low prediction errors strengthen the sense of agency, while high errors drive learning and model updates [17].

Quantitative Metrics and Experimental Protocols

Assessing the Sense of Embodiment

The multidimensional nature of presence and embodiment necessitates a multi-method approach to measurement. Researchers have developed both subjective and objective metrics to quantify these phenomena, each with distinct advantages and limitations as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Methods for Assessing Sense of Embodiment in Virtual Reality

| Method Type | Specific Measures | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective | Standardized questionnaires (e.g., embodiment scales) [17] | Direct access to subjective experience; Well-validated | Susceptible to demand characteristics; Retrospective |

| Behavioral | Proprioceptive drift [17] | Objective; Indirect measure of body ownership | Can dissociate from subjective reports; Task interference |

| Physiological | Skin conductance response to threats [17] | Automatic; Measures unconscious responses | Can be invasive; Requires careful interpretation |

| Neural | EEG, fMRI [17] [18] | High temporal (EEG) or spatial (fMRI) resolution | Expensive; Sensitive to movement artifacts |

Key Experimental Protocols

Several well-established experimental protocols have been developed to investigate and manipulate the sense of embodiment in controlled settings:

The Rubber Hand Illusion (RHI) Protocol: This classic paradigm has been adapted for VR to investigate body ownership. Participants view a virtual hand being stroked in synchrony with tactile stimulation applied to their real hand. The key measures include subjective questionnaires and proprioceptive drift—the displacement in perceived location of one's real hand toward the virtual hand [17]. Synchronous stimulation typically induces a stronger feeling of ownership compared to asynchronous stimulation.

Body Transfer Illusion Protocol: This protocol extends the RHI to full-body embodiment. Participants are embodied in a virtual body through a head-mounted display (HMD). Critical experimental manipulations include:

- Visuomotor Synchrony: The virtual body moves in correspondence with the participant's real movements tracked by motion capture.

- Multisensory Congruence: Providing congruent visual, tactile, and proprioceptive feedback during interactions.

- Perspective: Maintaining a consistent first-person perspective. The strength of embodiment is measured through questionnaire responses, physiological reactions to virtual threats, and changes in body perception [17].

Agency Manipulation Protocol: To specifically investigate the sense of agency, researchers introduce temporal or spatial discrepancies between executed movements and their visual consequences in VR. For example, introducing a slight delay (50-200ms) between hand movement and virtual hand movement or applying angular deviations to movement paths. Participants provide explicit judgments of agency while behavioral measures such as movement adaptation and implicit measures like sensory attenuation are recorded [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Findings on Predictive Mechanisms in Virtual Embodiment

| Experimental Paradigm | Neural Correlates/Measures | Key Findings | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Exposure Therapy for Anxiety | fMRI, EEG, self-report [15] | Equivalent or superior efficacy to in-vivo exposure; 70-90% response rates for specific phobias; Long-term effects generalize to real world | Anxiety disorders, PTSD, phobias [15] |

| VR Body Swapping | Proprioceptive drift, skin conductance, questionnaires [17] | Significant reduction in body ownership distortion in eating disorders; Up to 65% of patients show improved body image at 1-year follow-up | Eating and weight disorders [15] |

| Motor Imagery in VR-BCI | EEG sensorimotor rhythms, classification algorithms [18] | SEOWADE method: Achieved high classification accuracy (>85%) for motor imagery signals using orthogonal wavelet decomposition | Motor rehabilitation, stroke recovery [18] |

| fMRI Natural Image Decoding | Visual cortex activation patterns, deep learning models [18] | Successful reconstruction of perceived images from fMRI data using advanced neural networks | Basic neuroscience of perception, brain-computer interfaces [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Virtual Neuroscience Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Platforms | fMRI, EEG, MEG, fNIRS [18] [19] | Measure neural correlates of presence and embodiment; Localize brain activity; Track temporal dynamics |

| Brain-Computer Interfaces | Motor imagery EEG systems, SSVEP paradigms [18] | Enable direct communication between brain and virtual environment; Test closed-loop predictive processes |

| Motion Tracking Systems | Optical trackers, inertial measurement units (IMUs), hand trackers | Capture full-body movement for realistic avatar animation; Provide data for calculating prediction errors |

| Physiological Monitors | EDA, ECG, EMG, respiration sensors [17] | Objectively measure autonomic responses to virtual events; Provide implicit measures of emotional engagement |

| Advanced Analytics | Machine learning classifiers, deep neural networks, multimodal fusion algorithms [18] [19] | Decode neural representations; Identify predictive processing patterns; Analyze complex neuroimaging data |

Computational Approaches and Neuroimaging Advances

Machine Learning in Neuroimaging

The analysis of neuroimaging data in virtual neuroscience has been revolutionized by advanced machine learning approaches. These methods are particularly valuable for identifying complex patterns in brain activity associated with presence and predictive processing:

Multimodal Fusion Algorithms: Techniques such as Multiple Kernel Learning (MKL) combine information from structural MRI, functional MRI, and Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) to improve classification accuracy for neurological and psychiatric conditions [18]. For embodiment research, this enables linking structural brain measures with functional activation patterns during VR experiences.

Deep Learning Architectures: Siamese neural networks have been successfully applied to fMRI Independent Component Analysis (ICA) classification, enabling identification of resting-state networks with high accuracy even with limited training data [18]. These approaches facilitate the detection of subtle changes in brain network dynamics associated with altered states of embodiment.

EEG Signal Processing: Advanced methods like the SEOWADE algorithm employ orthogonal wavelet decomposition and channel-wise spectral filtering to improve the discriminability and generalizability of EEG signals in brain-computer interface applications [18]. This is particularly relevant for real-time assessment of cognitive states during VR immersion.

Experimental Workflow for Virtual Neuroscience Studies

A standardized experimental workflow ensures methodological rigor in virtual neuroscience research on presence. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates a comprehensive pipeline from experimental design to data analysis:

Figure 2: Virtual Neuroscience Experimental Workflow. This comprehensive pipeline illustrates the key stages in studying presence and embodiment, from experimental design through data collection and analysis to final interpretation.

Clinical Applications and Future Directions

The theoretical frameworks and experimental approaches discussed have significant translational potential in clinical neuroscience and drug development. VR-based paradigms that leverage predictive processing mechanisms are increasingly being deployed in therapeutic contexts:

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET): Meta-analyses confirm that VRET has efficacy comparable to traditional exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, with particular success in treating specific phobias, PTSD, and social anxiety [15]. The controlled nature of VR environments allows for precise manipulation of predictive relationships between actions and outcomes, facilitating fear extinction learning.

Eating and Weight Disorders: Research demonstrates that VR-enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy can produce outcomes superior to gold-standard CBT at one-year follow-up [15]. By altering the embodied experience of one's body size and shape through visuomotor and visuotactile stimulation, these interventions directly target the distorted internal body models that maintain these conditions.

Pain Management: VR produces significant reductions in acute and chronic pain through multiple mechanisms, including distraction, altered bodily perception, and modulation of predictive processes related to pain expectation [15]. The immersive nature of VR appears particularly well-suited to disrupting maladaptive predictive coding of pain signals.

Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated computational models of predictive processing in virtual environments, optimizing personalization of VR experiences based on individual neural and behavioral signatures, and establishing standardized neurocognitive biomarkers of presence and therapeutic response. The integration of real-time neurofeedback with VR systems represents a particularly promising avenue for creating closed-loop environments that dynamically adapt to users' neural states to enhance both experimental control and therapeutic efficacy.

In virtual neuroscience experiments, the concept of presence—the subjective feeling of "being there" in a virtual environment—is a cornerstone metric for evaluating the efficacy and ecological validity of a simulation [20]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the factors that modulate presence is critical for designing rigorous, reproducible, and effective virtual protocols. Historically, the focus has been on technological immersion as the primary driver of presence. However, a growing body of evidence underscores that individual user characteristics are equally, if not more, influential [20]. This technical guide delves into how three key individual differences—age, technological experience, and perceptual-motor style—fundamentally shape the experience of presence, framing this within the context of experimental design and measurement in virtual neuroscience.

The Multi-Faceted Nature of Presence and Its Measurement

Presence is not a unitary construct but a complex psychological state emerging from the interaction of cognitive, emotional, and physical responses to a virtual environment [20]. Its assessment has traditionally relied on two primary methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

- Subjective Questionnaires: Administered post-exposure, these tools (often using Likert scales) provide a direct, self-reported measure of the user's experience. However, they are susceptible to recall bias and may not capture the dynamic, real-time fluctuations of presence [20].

- Physiological Measures: There is a growing trend toward using objective, physiological markers to define presence, moving beyond subjective reports [20]. These measures capture the autonomic and central nervous system correlates of the user's state in real-time.

Table 1: Key Physiological Measures for Assessing Presence in VR

| Physiological Measure | Abbreviation | What It Measures | Relation to Presence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroencephalography | EEG | Electrical brain activity; good temporal resolution | Assesses alertness and cognitive processes; event-related potentials (ERPs) can detect neural responses to stimuli [20]. |

| Electrodermal Activity | EDA | Electrical changes on the skin from sweat gland activity | Modulated by arousal, attention, and stress—factors linked to emotional engagement in VR [20]. |

| Electrocardiography/ Photoplethysmography | ECG/PPG | Heart rate and its variability (HRV) | Used to assess emotional and physiological arousal states associated with presence [20]. |

| Electromyography | EMG | Muscle activity | Can capture subtle physical responses and readiness for action within the virtual environment [20]. |

| Inertial Measurement Units | IMU | Acceleration and velocity of body segments (head/limbs) | Head and body movement tracking provides behavioral quantification of engagement and interaction [20]. |

| Eye Tracking | - | Gaze control and fixation | Integrated into VR headsets to study visual attention and eye-hand coordination [20]. |

A significant challenge in the field is the non-specificity of these physiological variables; they are also used to quantify stress, mental workload, and other states, making it difficult to isolate a unique "presence signature" [20]. Furthermore, small sample sizes are common in VR studies, necessitating larger-scale prospective research to refine these models [20].

Age as a Determinant of VR Presence and Experience

Contrary to stereotypes, older adults do not experience diminished presence in VR. In fact, evidence suggests they may derive a more profound sense of presence than younger users, which has significant implications for designing therapeutic and assessment tools for an aging population.

Key Experimental Findings on Age and Presence

- Higher Presence in Older Adults: A pilot study directly comparing older adults (M=71.3 years) and younger adults (M=19.7 years) found that older adults reported a greater sense of presence across various VR environments, including meditation, exploration, and game-oriented scenarios [21]. This suggests that VR can be a highly effective medium for supporting Enhanced Activities of Daily Living (EADLs) in older populations.

- Positive Attitude Shift: A study with 76 older adults (57-94 years) revealed that initial, neutral attitudes towards head-mounted VR significantly improved to positive after a first exposure. A control group that watched time-lapse videos on a standard computer showed no such change in attitude [22]. This indicates that the direct experience of immersive VR is a powerful tool for overcoming initial hesitancy.

- Unexpected Cybersickness Profile: Contrary to the researchers' initial hypothesis, the pilot study found that older adults reported significantly less cybersickness than their younger counterparts [21]. Furthermore, a separate study confirmed that self-reported cybersickness was minimal in older adults and had no significant association with the VR exposure [22].

Table 2: Age-Related Differences in VR Experience from Empirical Studies

| Study Feature | Dilanchian et al. (2021) Pilot Study [21] | Huygelier et al. (2019) Acceptance Study [22] |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size (Older Adults) | 20 | 38 (HMD-VR group) |

| Mean Age (Older Adults) | 71.3 years | 72.2 years |

| Key Finding on Presence | Older adults reported a greater sense of presence. | Attitudes improved from neutral to positive after exposure. |

| Key Finding on Cybersickness | Older adults reported significantly less cybersickness. | Cybersickness was minimal and not associated with VR exposure. |

| System Usability/Workload | No significant age differences on most measures. | Not a primary focus, but acceptance was high. |

Underlying Mechanisms: Cognitive and Neural Changes

The enhanced presence in older adults may be linked to age-related neurological changes. While traditional views emphasize cognitive decline, modern neuroscience reveals a more complex picture of compensatory neural reorganization [23].

- Cognitive Control and Aging: Typical aging is associated with declines in processing speed, working memory, and inhibitory control, often linked to structural and functional changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [23]. One might expect this to impair the ability to engage with complex VR.

- Compensatory Mechanisms: However, the aging brain can exhibit increased functional connectivity and engage alternative neural networks to compensate for localized deficits [23]. This neural plasticity may allow older adults to achieve a deep state of presence through different cognitive pathways than younger adults. Furthermore, the novelty and richness of VR may provide a level of engagement that helps overcome everyday distractibility.

The Role of Perceptual-Motor Style in Shaping Presence

Beyond age, an individual's unique way of interacting with the world—their perceptual-motor style—is a critical but often overlooked factor in determining presence [20]. This concept refers to the distinctive, individualized strategies people employ to coordinate their perception and action.

Theoretical Framework: Predictive Processing and Embodiment

Theoretical models propose that presence emerges when users can correctly and intuitively enact their implicit (predictive processing) and explicit (intentions) embodied predictions within the VR environment [20]. In other words, presence is highest when the virtual world behaves as the user's brain and body expect it to. An individual's perceptual-motor style governs these predictions.

- Sources of Variability: This style, and consequently the feeling of presence, is not fixed. It varies with a person's sociocultural background, narrative, emotions, personal experiences, and expectations [20]. This variability explains why two individuals of the same age and technical proficiency can have vastly different presence experiences in the same VR simulation.

- The Gravity Prior Example: A key illustration of a shared perceptual-motor prior is the internal model of Earth's gravity. Research shows that motor actions like intercepting a falling ball are highly accurate when the virtual object obeys Earth's gravity, even with sparse visual information or when the object is occluded [24]. This demonstrates a deeply ingrained, shared prior used for predictive motor control. When VR physics align with this prior, presence is enhanced.

Visuomotor Mismatch: The Challenge for VR

A major challenge in VR design is the inherent visuomotor mismatch—the body is in a physical reality while being exposed to an optically artificial environment [25]. This mismatch can disrupt the user's perceptual-motor style.

- Motor Response Modulation: Studies comparing actions in VR and physical reality (PR) show that VR can induce measurable changes in motor responses. For example, in a catching task, the velocity of shoulder flexion was lower in VR than in PR, and muscle activity (EMG) onsets were delayed [25]. These deviations indicate that the unnatural virtual scene can distort the user's natural perceptual-motor coordination, potentially breaking presence.

- Impact on Perception: The fidelity of the virtual environment also matters. Judgments of naturalness for a rolling and falling virtual ball were highest and least variable when its kinematics were congruent with Earth gravity during both phases of motion [24]. This shows that violations of fundamental physical priors are detected at a perceptual level, negatively impacting the sense of realism and presence.

The following diagram illustrates the continuous feedback loop between a user's internal predispositions, the VR system, and the resulting sense of presence.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Individual Differences

To systematically investigate how individual differences shape presence, researchers can employ the following detailed experimental protocols, which integrate both subjective and objective measures.

Protocol 1: Evaluating Age-Related Differences in Presence

- Objective: To quantify and compare the sense of presence, cybersickness, and perceived workload between younger and older adults in immersive VR environments.

- Participants: Recruit two distinct age groups (e.g., 20 younger adults aged 18-25 and 20 older adults aged 65+) [21]. Ensure groups are matched on factors like gender and education where possible.

- VR Apparatus & Environments: Use a commercial head-mounted display (HMD) like the HTC Vive. Select a variety of commercial environments (e.g., a scenic exploration app like "Vesper Peak," a meditation app, a simple arcade game) to test generalizability [21].

- Procedure:

- Baseline Measures: Collect demographic data, technology experience questionnaires, and baseline cognitive assessments (e.g., MoCA) [22].

- VR Exposure: Participants experience each VR environment for a fixed duration (e.g., 5 minutes). They should be seated in a swivel chair for safety. An experimenter must be present to manage the equipment [21].

- Post-Exposure Metrics: After each environment, administer:

- A presence questionnaire (e.g., Igroup Presence Questionnaire).

- A cybersickness scale (e.g., Simulator Sickness Questionnaire).

- A workload inventory (e.g., NASA-TLX) [21].

- Data Analysis: Use mixed-model ANOVAs to compare presence, sickness, and workload scores between age groups across the different environments. Correlational analysis can explore relationships between presence, cognitive scores, and technology experience.

Protocol 2: Probing the Perceptual-Motor Style via Gravity Perception

- Objective: To determine the sensitivity of motor and perceptual systems to violations of physical laws (gravity) in VR, and its link to perceived naturalness.

- Participants: Skilled and novice participants relevant to the task (e.g., athletes for interceptive actions).

- VR Apparatus: A high-fidelity VR system with precise tracking (e.g., HTC Vive or CAVE) that can simulate projectile motion with adjustable physics parameters [24].

- Virtual Task: Participants are tasked with hitting or catching a virtual ball that rolls down an incline and then falls in air [24].

- Independent Variables:

- Dependent Variables:

- Motor Timing: Accuracy in intercepting the ball (timing error).

- Perceptual Judgment: After each trial, participants report whether the ball's motion was "natural" or "unnatural" on a scale [24].

- Data Analysis: Compare interception timing errors across gravity conditions. Analyze naturalness ratings as a function of gravity congruence. A strong link between accurate motor timing and high naturalness ratings for Earth-gravity conditions would indicate the use of a shared internal model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

For researchers embarking on studies of individual differences in VR, the following tools and materials are essential.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Presence Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platform | HTC Vive, Oculus Rift | Provides the immersive environment; must be consistent across participants to standardize immersion levels [21] [22]. |

| Physiological Data Acquisition System | BioPac system, LabChart, Immersion Neuroscience platform | Synchronizes and records physiological signals (EEG, ECG, EDA, EMG) for objective quantification of user state [20] [26]. |

| Subjective Measure Questionnaires | Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ), Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ), NASA-TLX, System Usability Scale (SUS) | Provides standardized, quantitative measures of subjective presence, cybersickness, mental workload, and system usability [21] [22]. |

| Motion Tracking Sensors | Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), integrated HMD tracking | Quantifies head and body movements as behavioral correlates of engagement and perceptual-motor style [20]. |

| Cognitive Assessment Battery | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Trail Making Test | Assesses global cognitive status and specific executive functions that may mediate age-related differences in VR interaction [23] [22]. |

| Data Analysis & Visualization Software | R/RStudio, Python (Pandas, NumPy), ChartExpo | Performs statistical analysis, machine learning modeling, and creates clear visualizations of complex quantitative data [27]. |

The following workflow diagram maps the sequential process of conducting a comprehensive VR presence study, from participant screening to data synthesis.

The experience of presence in virtual environments is a profoundly individual phenomenon, sculpted by an interaction between the user's age, their lifetime of technological and worldly experiences, and their unique perceptual-motor style. For the virtual neuroscience researcher, acknowledging and systematically accounting for these differences is not merely a methodological refinement—it is a necessity. The future of the field lies in moving beyond one-size-fits-all VR design and towards personalized, adaptive virtual environments that can accommodate individual differences in cognitive style, physical capability, and neural processing. This will be key to unlocking the full potential of VR as a tool for rigorous scientific discovery, effective clinical intervention, and robust pharmaceutical development.

Applied Immersive Neuroscience: From Empathy Induction to Knowledge Acquisition

Leveraging Neurologic Immersion to Foster Empathy and Prosocial Behavior in Clinical Training

This technical guide examines the application of neurologic immersion within virtual reality (VR) environments to enhance empathy and prosocial behavior among healthcare professionals. Immersion, defined as the neurophysiologic value the brain assigns to experiences, serves as a quantifiable biomarker for predicting behavioral outcomes including empathic concern and helping behaviors. Through standardized experimental protocols and advanced physiological measurement, neurologic immersion provides a mechanistic bridge between VR-based training and improved patient care outcomes. This whitepaper details the methodological frameworks, measurement technologies, and implementation protocols for integrating neurologic immersion into clinical education, with particular relevance for researchers investigating presence and immersion in virtual neuroscience experiments.

Virtual reality has emerged as a promising tool for clinical training, yet evidence for its efficacy has been mixed due to reliance on self-reported measures rather than objective neurophysiologic data [28]. Neurologic Immersion (distinguished from general immersion by its capitalization as a specific metric) represents a convolved neurophysiologic measure that captures the value the brain assigns to experiences through signals associated with attention and emotional resonance [28]. This metric, which correlates with dopamine binding in the prefrontal cortex and oxytocin release from the brainstem, provides an objective foundation for quantifying the impact of VR experiences on clinical trainees [28].

Within the broader context of presence and immersion research in virtual neuroscience, Immersion offers a standardized approach to linking technological immersion with psychological presence and behavioral outcomes. Studies demonstrate that VR generates approximately 60% more neurologic Immersion than equivalent 2D video content, resulting in significantly increased empathic concern and prosocial behavioral intentions among healthcare trainees [28]. This neurophysiologic response creates a powerful pathway for enhancing the understanding of patient experiences and challenges, potentially reducing provider burnout while improving patient care quality [28] [29].

Theoretical Framework: From Immersion to Prosocial Action

The relationship between neurologic Immersion and prosocial behavior operates through a defined psychological pathway. Research indicates that immersion enhances the sense of presence, which subsequently fosters state empathy and ultimately leads to increased prosocial intentions [30]. This pathway is particularly relevant in clinical training, where empathic concern motivates behaviors that improve patient outcomes.

Table 1: Empathy-Related Constructs in Clinical VR Training

| Construct | Definition | Role in Clinical Training |

|---|---|---|

| Affective Empathy | Experiencing isomorphic feeling in relation to others with clear self/other differentiation [29] | Enables shared emotional understanding of patient experiences |

| Cognitive Empathy | Understanding others' emotions through perspective-taking and online simulation [29] [31] | Facilitates accurate assessment of patient needs and concerns |

| Empathic Concern | Desire for wellbeing of others motivating helping behavior [28] [29] | Directly translates to improved patient care and support behaviors |

| Compassion | Emotional and motivational state of care for others' wellbeing [29] | Reduces burnout while maintaining connection with patients |

The "empathy machine" potential of VR emerges from its capacity to trigger embodied experiences through perspective-taking. When healthcare providers virtually step into patients' experiences, they develop a more nuanced understanding of social determinants of health, including socioeconomic barriers, language challenges, and systemic obstacles to care [32]. This perspective-taking forms the foundation for the relationship between immersion and prosocial behavior that is essential to effective clinical practice.

Measurement and Assessment Protocols

Quantifying Neurologic Immersion

The measurement of neurologic Immersion employs commercial neurophysiology platforms that generate a 1Hz data stream by applying algorithms to photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors [28]. This approach captures physiological signals from cranial nerves associated with attention and emotional resonance, producing the convolved Immersion metric that predicts individual and population outcomes [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics in Neurologic Immersion Studies

| Metric | Measurement Approach | Clinical Training Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Average Immersion | Mean neurologic Immersion during entire VR exposure [28] | Baseline engagement with patient narrative |

| Peak Immersion | Cumulative sum of Immersion peaks above individual threshold [28] | High-impact moments driving behavioral change |

| Empathic Concern | Self-report scales measuring desire to help others [28] | Motivation to improve patient care behaviors |

| Prosocial Behavior | Observable helping behaviors post-exposure (e.g., volunteering) [28] | Real-world translation of training outcomes |

Research protocols typically employ baseline measurements before VR exposure, with all reported Immersion values representing changes from this individual baseline to control for personal differences [28]. This standardized approach enables meaningful comparison across participants and training modalities.

Multimodal Assessment Framework

Beyond neurologic Immersion, comprehensive assessment of empathy in VR training incorporates multiple measurement modalities:

- Eye-tracking patterns: Individuals with high empathy demonstrate distinct visual attention to socially relevant cues, including increased focus on facial expressions and body postures that signal emotional states [31]

- Decision-making metrics: Empathic profiles correlate with cooperative versus competitive decision-making styles in simulated clinical scenarios [31]

- Behavioral measures: Post-exposure prosocial behaviors, such as volunteering to help other students or increased engagement with challenging patients, provide real-world validation of training efficacy [28]

- Machine learning integration: Combined behavioral and eye-tracking data classified individuals according to empathy dimensions (perspective-taking, emotional understanding, empathetic stress, empathetic joy) with significant accuracy [31]

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized VR Empathy Training Protocol

The Making Professionals Able Through Immersion (MPATHI) program exemplifies an effective VR-based empathy training protocol for healthcare providers [32]. This evidence-based approach includes:

Participant Profile: Healthcare providers (dentists, physicians, nurses) with active clinical responsibilities during training period [32].

VR Stimulus Development:

- Content: Patient journey narrative following individuals facing socioeconomic and language barriers

- Format: 180° VR captured using Insta360 Pro2 cameras (8K resolution) viewed through Meta Quest 2 headsets

- Narrative Structure: Boorstin's scripting principles with chronological structure depicting multiple clinical interactions [28]

- Runtime: 5 minutes 23 seconds for standard stimulus [28]

Experimental Procedure:

- Baseline measurement: 5-minute resting state neurologic Immersion recording

- VR exposure: Randomized assignment to VR (n=35) or 2D (n=35) condition using identical narrative content

- Post-exposure measures: Immediate assessment of empathic concern and prosocial intentions

- Behavioral follow-up: Observation of volunteering behavior opportunities within 48 hours

This protocol demonstrated significantly higher neurologic Immersion in VR participants, with subsequent increases in empathic concern and prosocial behavior compared to the 2D control group [28].

Technical Specifications for Optimal Immersion

Achieving neurologic Immersion requires specific technical parameters:

- Display: Meta Quest 2 headsets with 1832 × 1920 per eye resolution, 90Hz refresh rate, and 89° horizontal field of view [28]

- Sensors: Rhythm+ PPG sensors (Scosche Industries) for physiological data collection [28]

- Interaction: Degree of user control over tactile stimulation and environmental interaction significantly impacts presence and embodiment [33]

- Narrative quality: Professional production values with clinical accuracy validation by subject matter experts [28]

Diagram 1: Pathway from VR Technology to Prosocial Behavior

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Neurologic Immersion Research

| Item | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Headsets (Meta Quest 2) | Presents 180° VR content with 6 degrees of freedom | Display of patient journey narratives with realistic spatial presence [28] |

| PPG Sensors (Rhythm+ by Scosche) | Captures physiological signals for neurologic Immersion algorithm | Measurement of attention and emotional resonance during VR exposure [28] |

| Immersion Neuroscience Platform | Convolves physiological signals into 1Hz Immersion metric | Quantification of neurophysiologic response to patient narratives [28] |

| 360° VR Cameras (Insta360 Pro2) | Captures high-resolution immersive video content | Creation of authentic patient journey experiences in clinical settings [28] |

| Eye-tracking Integration | Records visual attention patterns during VR exposure | Identification of empathy-specific viewing patterns in social scenarios [31] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Classifies participants by empathy dimensions using behavioral and eye-tracking data | Automated assessment of empathy levels in organizational settings [31] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for VR Empathy Studies

Applications in Clinical Training and Healthcare Education

The translation of neurologic Immersion research to clinical training environments has demonstrated significant potential across multiple healthcare domains:

Empathy Training for Social Determinants of Health

The MPATHI program successfully improved knowledge, skills, and attitudes of healthcare providers for care delivery to families facing socioeconomic and language barriers [32]. Through perspective-taking narratives that place providers in the role of patients navigating systemic challenges, participants developed greater understanding of barriers such as:

- Health literacy limitations and complex medical paperwork

- Language barriers and interpreter access challenges

- Transportation and financial constraints affecting care adherence

- Cultural differences in health beliefs and practices

Nursing Education and Patient Journey Understanding

In nursing education, VR-based neurologic Immersion created 60% greater engagement with patient experiences compared to traditional methods, resulting in enhanced empathic concern and increased volunteering to help other students [28]. The patient journey narrative, following a female patient with chronic illness through multiple clinical interactions, provided nursing students with deeper insight into the emotional and physical challenges patients face across the care continuum.

Organizational Empathy in Healthcare Systems

Beyond individual patient interactions, neurologic Immersion approaches show promise for developing organizational empathy - the balance between organizational skills and empathic abilities in workplace behaviors [31]. This application is particularly relevant for healthcare administrators and clinical leaders who must balance operational demands with staff wellbeing and patient-centered care.

Neurologic Immersion represents a validated, measurable neurophysiologic mechanism through which VR training enhances empathy and prosocial behavior in clinical education. By quantifying the brain's assignment of value to experiences through attention and emotional resonance, researchers and educators can design more effective training interventions that translate to meaningful improvements in patient care.

Future research directions should address several critical areas:

- Longitudinal studies tracking the persistence of empathy and prosocial behavior changes beyond immediate post-exposure measures

- Individual difference factors moderating response to VR empathy interventions, including prior clinical experience and baseline empathy levels

- Optimal dosing parameters for VR empathy training, including session duration, frequency, and narrative intensity

- Integration with artificial intelligence for real-time adaptation of VR content based on physiological response metrics

- Cross-cultural validation of neurologic Immersion measures across diverse healthcare contexts and patient populations

As VR technology continues to evolve, the precise measurement and application of neurologic Immersion will play an increasingly vital role in cultivating the empathic, prosocial healthcare providers essential to patient-centered care systems.

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool for experiential learning, yet its effectiveness is profoundly influenced by the complex interplay between technological immersion, the subjective psychological state of presence, and the specific type of knowledge being acquired. Within virtual neuroscience experiments, immersion is an objective property of the system's ability to provide a vivid, multi-sensory, and interactive environment, while presence is the subjective psychological experience of "being there" within that virtual environment [34] [20]. This technical guide posits that optimizing VR for learning requires a tailored approach grounded in the fundamental neurocognitive distinction between knowledge types. According to Anderson's ACT-R theory, declarative knowledge ("what" information, represented as chunks and facts) and procedural knowledge ("how" information, represented as production rules for actions) involve distinct cognitive encoding, consolidation, and retrieval mechanisms [35]. This paper provides an in-depth analysis of how VR immersion levels should be strategically matched to these knowledge types to maximize learning efficacy, presence, and knowledge transfer, with a specific focus on methodologies relevant to research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Linking Immersion, Presence, and Knowledge Acquisition

A Neurocognitive Framework for VR Learning

The relationship between immersion and presence is not linear but is cognitively mediated. Higher levels of technological immersion—characterized by sensory fidelity (quality and breadth of sensory information), interactivity (speed, range, and mapping of user control), and embodiment—typically foster a stronger sense of presence [34]. Presence, in turn, is hypothesized to enhance learning by leveraging embodied cognition, where sensory-motor experiences and the feeling of being in a situation provide a richer context for encoding and retrieving information [34] [36]. However, this process is moderated by the perceptual-motor style of the individual, a neurophysiological concept describing a person's unique, characteristic strategies for interacting with their environment [20]. This implies that the same immersive system can elicit varying levels of presence and learning outcomes across different users.

Declarative vs. Procedural Knowledge: Cognitive Demands

The differentiation between declarative and procedural knowledge is critical for VR design:

- Declarative Knowledge: Its acquisition benefits from deep encoding and contextual cues. VR can enhance this by situating facts within rich, multi-sensory virtual contexts, facilitating deep processing and memory formation [35].

- Procedural Knowledge: Its acquisition requires the compilation and strengthening of condition-action rules through repeated, often physical, practice. VR is ideal for procedural learning as it allows for safe, realistic rehearsal of tasks, creating strong situational memories that support the transfer of skills to real-world contexts [35] [37].

Failure to align the immersive experience with the cognitive demands of the target knowledge type can lead to extraneous cognitive load, thereby hindering learning [35].

Technical Parameters for Tailoring VR Immersion

The design of a VR system for learning involves the careful calibration of specific technical parameters that directly influence immersion and, consequently, the potential for presence and effective learning.

Table 1: Technical Parameters of VR Immersion for Knowledge Acquisition

| Parameter | Definition | Impact on Presence & Learning | Optimal Use for Declarative Knowledge | Optimal Use for Procedural Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory Fidelity | Quality and realism of sensory input (visual, auditory, haptic) [34]. | Higher fidelity increases presence but may raise cognitive load if irrelevant [35]. | High-quality visuals and audio to create an engaging context for facts. | Critical for realistic simulation; haptic feedback is essential for psychomotor skills. |

| Interactivity & User Control | The extent and precision of user interaction with the virtual environment [34]. | Enhances agency and presence; poor mapping can cause cyber sickness [34]. | Moderate; navigation (e.g., teleportation) to explore informational scenes [36]. | High; requires precise, real-time control over tools and actions to practice procedures. |

| Embodiment | The representation and perception of having a body in the virtual world. | Strong embodiment reinforces the sense of presence and supports embodied cognition [37]. | A virtual body to enhance spatial awareness and contextual learning. | A fully articulated, responsive virtual body is crucial for motor skill acquisition. |

| Narrative & Context | The use of story or scenario to frame the learning content. | Increases emotional engagement and motivation, supporting memory encoding. | Highly beneficial for providing a memorable structure for factual information. | Essential for providing a realistic purpose and context for procedural actions. |

Quantitative Evidence: Differential Impact of VR on Knowledge Types

Recent empirical research provides strong evidence for the differential impact of VR immersion on declarative and procedural knowledge, supporting the need for a tailored approach.

A 2025 study employed a 2x2 mixed design with 64 college students, comparing high-immersion VR (HTC Vive Pro) to low-immersion desktop VR for learning both declarative (thyroid disease facts) and procedural (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) knowledge [35]. The results, summarized in the table below, demonstrate that while high immersion benefits both knowledge types, its impact on associated cognitive and affective factors differs significantly.

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes of High vs. Low Immersion on Knowledge and Affective/Cognitive Factors [35]

| Learning Dimension | Declarative Knowledge | Procedural Knowledge |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Outcomes | Significant improvement with high immersion (large effect size) | Significant improvement with high immersion (large effect size) |

| Sense of Presence | Enhanced in high-immersion group | Enhanced in high-immersion group |

| Intrinsic Motivation | Enhanced in high-immersion group | Enhanced in high-immersion group |

| Self-Efficacy | Enhanced in high-immersion group | Enhanced in high-immersion group |

| Cognitive Load | Reduced in high-immersion group | No significant reduction observed |

| Knowledge Transfer | Not specifically measured | Shows the largest effect sizes for procedural training in VR [37] |

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2024 further strengthens the case for VR in procedural training, finding a significant positive medium effect size overall for immersive procedural training compared to less immersive environments, with knowledge transfer outcomes showing the largest effect sizes [37]. This is critical for fields like surgery or equipment operation in drug development, where skills must be applied in the real world. Furthermore, a dissertation study confirmed that VR training not only helps learners acquire procedural knowledge but also significantly enhances its retention over time, reducing recall errors compared to traditional video and manual training [38].

Experimental Protocols for VR Learning Research