Real-Time fMRI Motion Tracking Software: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging (rt-fMRI) motion tracking software, a critical tool for enhancing data quality in both neuroscience research and clinical drug...

Real-Time fMRI Motion Tracking Software: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging (rt-fMRI) motion tracking software, a critical tool for enhancing data quality in both neuroscience research and clinical drug development. It covers the foundational principles of why motion tracking is essential, explores specific methodological applications from quality assurance to neurofeedback, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing performance, and reviews frameworks for the quantitative validation and comparison of different software tools. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current knowledge to help teams effectively integrate rt-fMRI motion analytics into their workflows to improve reliability and reduce costs.

The Critical Need for Real-Time fMRI Motion Tracking in Biomedical Research

Application Notes: Real-Time Motion Tracking in fMRI

Head motion remains a fundamental obstacle in functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), disrupting activation patterns and reducing the reliability of data, particularly in clinical populations and challenging scanning environments. Real-time motion tracking and correction technologies have emerged as critical solutions to this pervasive challenge, directly enhancing data quality and fidelity for research and drug development.

Core Quantitative Improvements from Motion Correction

The implementation of prospective motion correction (PMC) systems demonstrates significant, quantifiable benefits for fMRI data quality. The following table summarizes key performance metrics reported from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements in fMRI Data with Motion Correction

| Metric | Improvement with PMC | Technical Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (tSNR) | 23% increase | Fetal fMRI with U-Net-based tracking and rigid registration [1] | |

| Dice Similarity Index | 22% increase | Measures image registration quality in fetal fMRI time series [1] | |

| tSNR | General increase | Task-based fMRI at 7T using MS-PACE technique [2] | |

| Residual Motion | Significant, consistent reduction | Task-based fMRI at 7T; reduces artefactual activations [2] | |

| tSNR & Activation Recovery | Improved tSNR; restored motor cortex activation | PMC with markerless tracking under controlled head motion [3] |

Key Methodological Approaches

Current research explores multiple technological pathways for mitigating motion artifacts:

- Prospective Motion Correction (PMC): This approach tracks head motion and uses the acquired pose data to update the imaging sequence in real-time, ensuring the field-of-view remains aligned with the moving head. This is applicable across a wide range of sequences [3] [4].

- Retrospective Motion Correction: This method corrects for the effects of motion after data acquisition during the reconstruction stage. Techniques like DISORDER use specialized sampling schemes to improve the robustness of motion estimation and correction from the acquired k-space data [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Real-Time Fetal Head Motion Correction

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing a U-Net-based prospective motion correction system for fetal fMRI, a particularly challenging application due to unpredictable and large-scale motion [1].

- Objective: To track fetal head motion and prospectively adjust slice positioning in real-time to mitigate motion artifacts in fMRI time series.

- Primary Materials:

- fMRI Scanner

- Real-time processing platform

- U-Net segmentation model (pre-trained for fetal head segmentation)

- Rigid registration algorithm

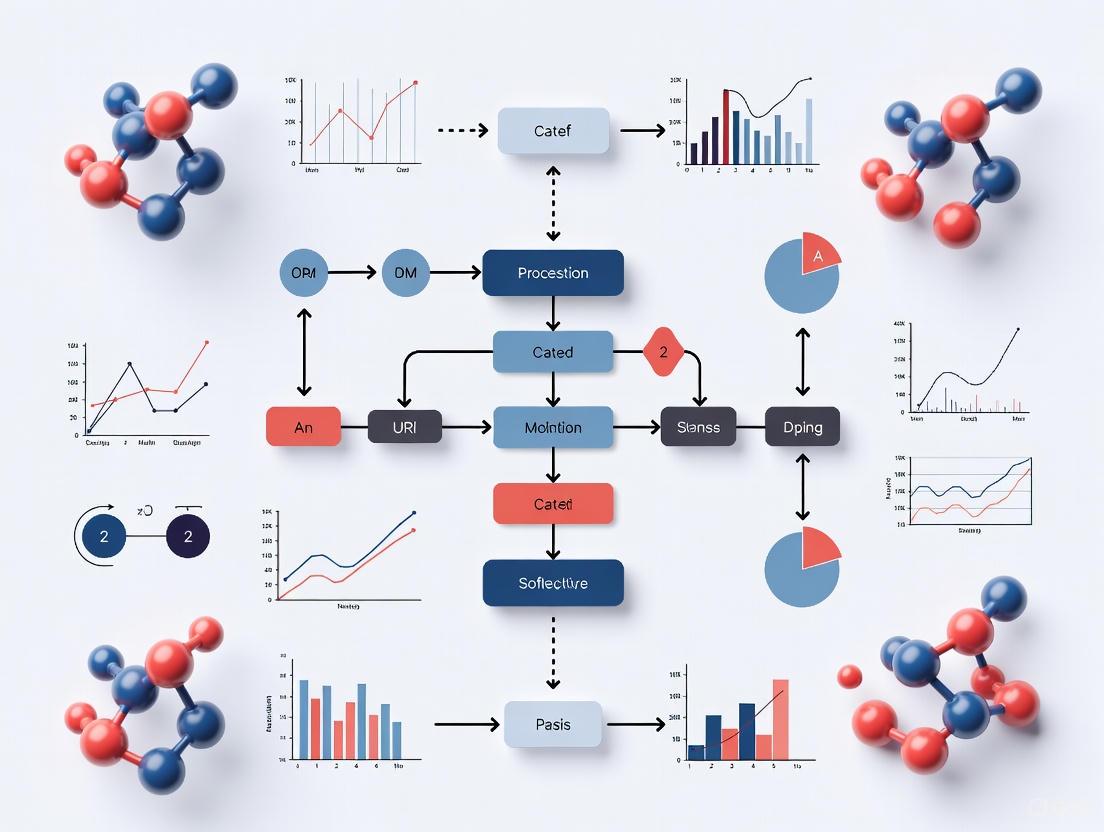

- Workflow Diagram:

- Procedure:

- Initial Acquisition: Acquire a single fMRI volume (repetition time, TR) as the initial reference.

- Real-Time Segmentation: For each subsequently acquired frame (TRn), process the data using a U-Net-based algorithm to perform automatic segmentation of the fetal head.

- Motion Estimation: Perform a rigid registration between the newly segmented head and the reference volume to calculate the transformation matrix defining the head's motion.

- Prospective Correction: The calculated motion parameters are fed forward to the scanner's pulse sequence. The system uses this data to adjust the slice position and orientation for the next acquisition (TR{n+1}).

- Iteration: This process repeats every TR, enabling real-time correction with a one-TR latency [1].

Protocol: Validation of Motion-Corrected Morphometry

This protocol describes a method for validating the concordance of morphometric measures derived from motion-corrected structural images against conventional images, which is crucial for establishing reliability in pediatric or clinical cohorts [4].

- Objective: To validate a retrospective motion correction technique (DISORDER) for T1-weighted brain morphometry in children by comparing its output to conventional acquisitions.

- Primary Materials:

- 3T MRI Scanner

- T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (conventional and DISORDER)

- Automated segmentation software (FreeSurfer, FSL-FIRST, HippUnfold)

- Statistical analysis software (e.g., R, SPSS)

- Workflow Diagram:

- Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire two T1-weighted MPRAGE 3D datasets from each participant in the same scanning session: one using a conventional linear phase encoding scheme and one using the DISORDER sampling scheme.

- Image Scoring: Have trained reviewers blind-score the conventional MPRAGE images as "motion-free" or "motion-corrupt" based on visible artifacts.

- Morphometric Processing: Process both the conventional and DISORDER datasets through identical automated analysis pipelines (e.g., FreeSurfer for cortical measures, FSL-FIRST for subcortical grey matter, HippUnfold for hippocampal volumes) to extract brain morphometric measures.

- Statistical Validation:

- Use the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to determine the agreement between measures from conventional and DISORDER images.

- Employ the Mann-Whitney U test to determine if the percentage differences in measures between motion-corrupt conventional data and DISORDER data are significantly greater than the differences between motion-free conventional data and DISORDER data [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Software for fMRI Motion Tracking Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| U-Net Segmentation Model | Real-time, automatic segmentation of anatomical structures (e.g., fetal head) from MRI data. | Core component for feature identification in prospective motion correction pipelines [1]. |

| Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) Framework | Real-time tracking of head pose with subsequent adjustment of the imaging field-of-view. | Mitigates motion artifacts prospectively; can be markerless or use external markers [3]. |

| DISORDER Sampling Scheme | Retrospective motion correction via incoherent k-space sampling for improved motion estimation. | A software-based solution integrated into the acquisition sequence to enhance motion tolerance [4]. |

| MS-PACE Technique | Real-time, prospective multislice-to-volume correction without external tracking equipment. | Particularly beneficial for task-based fMRI at ultra-high field (7T) [2]. |

| Automated Morphometry Software (FreeSurfer, FSL-FIRST) | Quantification of cortical and subcortical brain structures from structural MRI. | Used as the benchmark for validating the output of motion-corrected imaging protocols [4]. |

| Enhanced Tracking-Learning-Detection (ETLD) Framework | Automatic, real-time, markerless motion tracking in dynamic MRI (e.g., cine MRI for radiotherapy). | Integrated with segmentation models for precise target volume coverage in MRI-guided interventions [5]. |

Framewise Displacement (FD) is a quantitative metric that summarizes head movement over the course of a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan. It serves as a proxy for head motion and is widely used to identify data volumes (frames) contaminated by excessive motion, which can be excluded (censored) from analysis to improve data quality and result validity [6].

FD is calculated from the six realignment parameters (translations in the x, y, and z planes and rotations around the x, y, and z axes) generated during the rigid-body realignment that is a standard step in fMRI preprocessing. These parameters estimate frame-to-frame movement [6]. The formula for calculating FD from these parameters incorporates the derivatives of these six movements, converting rotational displacements from radians to millimeters based on an estimated radius from the center of the head [6]. FD relies on absolute values of differences and is always positive, with larger numbers reflecting more total movement [6].

FD in Practice: Application and Protocols

Real-Time Motion Monitoring in fMRI

Real-time motion monitoring, using software such as Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring (FIRMM), represents a significant advancement in mitigating motion artifacts during acquisition. FIRMM uses rapid image reconstruction and rigid-body alignment to estimate frame-by-frame movement, providing visual feedback to researchers and technicians based on estimated movement [6]. This approach is effective for both resting state and task-based fMRI paradigms [6].

Table 1: Real-Time Feedback Thresholds in FIRMM Software [6]

| Feedback Color | FD Threshold | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| White Cross | < 0.2 mm | Acceptable motion level |

| Yellow Cross | 0.2 mm to < 0.3 mm | Moderate motion warning |

| Red Cross | ≥ 0.3 mm | High motion level |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the implementation of a real-time motion monitoring and feedback system:

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Real-Time FD Feedback

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating the efficacy of real-time feedback in reducing head motion during task-based fMRI [6].

- Objective: To reduce in-scanner head motion during an auditory word repetition task using real-time FD feedback.

- Participants: Adult participants (aged 19–81), pseudorandomly assigned to a feedback or no-feedback control group.

- FD Calculation & Feedback Setup:

- Use real-time calculation of realignment parameters to estimate participant motion (e.g., via FIRMM software).

- Set FD thresholds for visual feedback display: white cross for FD < 0.2 mm, yellow for 0.2 mm ≤ FD < 0.3 mm, and red for FD ≥ 0.3 mm.

- Procedure:

- Instruction: For the feedback group, instruct participants that a colored cross will change based on their movement and that their goal is to "keep the cross white."

- Scanning: Acquire BOLD functional images using a standard sequence (e.g., multiband echo planar imaging).

- Between-run Feedback: After each run, show participants a "Head Motion Report" with a percentage score (0-100%) and a graph of their motion over time. Encourage them to improve their score on the next run.

- Outcome Measures:

- Compare the average FD and the amount of usable data (frames with FD ≤ 0.2 mm) between the feedback and control groups.

- Statistical analysis (e.g., linear mixed-effects model) typically shows a significant reduction in average FD and an increase in usable data in the feedback group [6].

Post-Hoc Data Quality Control Protocol

After data collection, FD is used for quality control and censoring of motion-contaminated volumes.

- Objective: To identify and exclude high-motion fMRI volumes from subsequent statistical analysis.

- Data Input: The six realignment parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) output from the volumetric realignment step in fMRI preprocessing.

- FD Calculation:

- Compute the backward difference for each of the six realignment parameters.

- Convert the rotational displacements (pitch, roll, yaw) from radians to millimeters by multiplying by a radius. A common convention is to use a default radius of 50 mm for an average head, though this can vary.

- FD for volume t is the sum of the absolute values of these six derivative measures [6].

- Censoring (or "Scrubbing"):

- Set an FD threshold for identifying a "bad" frame. A common, conservative threshold is FD > 0.2 mm [7], though studies may use values up to 0.5 mm depending on the research question and sample.

- Flag all frames where FD exceeds the chosen threshold.

- Exclude these flagged frames from the first-level model analysis. It is also common practice to censor one or two frames following a high-motion frame, as the spin history effect can persist.

Table 2: Common FD Thresholds and Their Applications in Post-Hoc Analysis

| FD Threshold | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|

| FD > 0.1 mm | Ultra-conservative threshold for high-resolution studies or populations with very low motion. |

| FD > 0.2 mm | Standard conservative threshold for censoring in adult and infant populations [7]. |

| FD > 0.3 mm | Moderate threshold for studies where minimal data loss is a priority. |

| FD > 0.5 mm | Liberal threshold, often used for identifying major motion events. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for fMRI Motion Tracking and Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Function | Example Software / Library |

|---|---|---|

| Real-Time Monitoring Software | Provides instant visual feedback on participant motion during scanning to improve data quality. | FIRMM [6] [7] |

| fMRI Preprocessing Pipeline | Performs volumetric realignment and calculates the six motion parameters essential for FD derivation. | FSL (MCFLIRT), SPM, AFNI |

| FD Calculation Script | Computes Framewise Displacement from the six realignment parameters. | In-house scripts (Python, MATLAB, R), fsl_motion_outliers |

| Data Censoring Tool | Removes motion-contaminated volumes from the time series based on FD thresholds. | AFNI's 1d_tool.py, SPM, CONN toolbox |

| Motion Parameter Database | A repository for sharing motion data and analysis scripts to promote reproducibility. | OpenNeuro [6], GitHub [6] |

Critical Considerations for Researchers

Threshold Selection is Context-Dependent: The optimal FD censoring threshold is not universal. Researchers must balance the risk of retaining motion-contaminated data against the statistical power loss from excessive data censoring. This balance may vary based on the participant population (e.g., clinical vs. healthy controls), scan duration, and the specific analysis being performed [6].

FD Summarizes but Does Not Fully Correct: While FD is an excellent summary metric for identifying bad volumes, it is a proxy for motion. Censoring based on FD is only one part of a comprehensive motion mitigation strategy, which should also include including the realignment parameters as nuisance regressors in the statistical model [6].

Real-Time Feedback is a Powerful Proactive Tool: Implementing real-time FD monitoring allows for intervention during the scan, maximizing the chances of acquiring high-quality data. This has been proven effective in populations ranging from infants [7] to older adults [6], and across different experimental paradigms.

Motion artifacts represent one of the most significant methodological challenges in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), potentially compromising data integrity from basic research to clinical drug trials. Head motion during fMRI acquisition introduces systematic biases that distort blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals, leading to consequences ranging from false activations to completely spurious brain-behavior relationships. Even with highly compliant participants, involuntary sub-millimeter head movements systematically alter fMRI data, with more pronounced effects in clinical populations and developmental studies where motion is more prevalent [8]. The technical challenge posed by motion cannot be overstated and has motivated the creation of behavioral interventions, real-time motion tracking software, and advanced post-processing methodologies [8]. Understanding these consequences and implementing robust mitigation protocols is particularly crucial for drug development studies, where erroneous conclusions can have significant scientific and financial implications.

Quantifying the Consequences: Systematic Bias and Spurious Associations

The impact of motion on fMRI data extends beyond simple image degradation to complex confounding of statistical outcomes. Motion artifacts introduce systematic variance that can mimic, obscure, or distort genuine neural signals, fundamentally threatening the validity of functional connectivity (FC) and brain-wide association studies (BWAS).

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Motion Artifacts on fMRI Outcomes

| Impact Category | Specific Effect | Quantitative Evidence | Primary Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| False Positive Findings | Spurious brain-behavior relationships | 42% (19/45) of traits showed significant motion overestimation | [8] |

| False Negative Findings | Underestimation of true trait-FC effects | 38% (17/45) of traits showed significant motion underestimation | [8] |

| Data Quality Reduction | Decreased temporal signal-to-noise ratio | 23% reduction in tSNR in uncorrected fetal fMRI | [1] |

| Image Quality Reduction | Lower image similarity and registration accuracy | 22% reduction in Dice similarity index in uncorrected data | [1] |

| Functional Connectivity Bias | Systematic alteration of connectivity patterns | Strong negative correlation (Spearman ρ = -0.58) between motion and long-distance FC | [8] |

Recent large-scale analyses using the Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks (SHAMAN) method have quantified how motion disproportionately affects studies of traits inherently correlated with movement, such as psychiatric disorders. After standard denoising without motion censoring, nearly half of examined traits showed significant motion-related overestimation effects, while more than a third showed significant underestimation [8]. This systematic bias is particularly problematic because motion artifact has been shown to be spatially systematic, causing decreased long-distance connectivity and increased short-range connectivity, most notably in the default mode network [8]. This specific pattern has led previous investigators to erroneously conclude that conditions like autism decrease long-distance FC when, in fact, their results were driven primarily by increased head motion in the autistic study participants [8].

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Motion Corrupts the fMRI Signal

The detrimental effects of head motion on fMRI data arise from multiple physical and technical mechanisms that extend far beyond simple image misalignment. These complex interactions between movement and MR physics explain why retrospective correction alone is often insufficient for complete artifact removal.

Multifaceted Origins of Motion Artifacts

Motion artifacts in fMRI originate from several distinct sources, each contributing to signal corruption through different physical mechanisms. While single-shot EPI sequences effectively "freeze" motion within individual 2D slices, the sequential acquisition of multiple slices over several seconds makes volumetric fMRI data highly susceptible to inter-volume inconsistencies [9]. These inconsistencies manifest as complex signal modulations rather than simple image displacement.

Table 2: Physical Mechanisms of Motion Artifacts in fMRI

| Mechanism Category | Specific Effect | Severity (at 3T) | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Transmit Effects | Motion relative to transmit RF fields | High | Contrast modulation, spin-history effects |

| RF Receive Effects | Motion relative to receiver coils | High | Intensity modulation due to changing sensitivity profiles |

| Spatial Encoding | Motion relative to encoding coordinates | High | Partial-volume effect modulation |

| Spatial Encoding | Within-volume motion during multi-slice acquisition | Medium | Inconsistent 3D data, slice crosstalk |

| Magnetic Field Effects | Motion-induced B0 field modulation | Medium | Local distortion and blurring alterations |

| Magnetic Field Effects | Altered susceptibility distributions with rotation | Medium | B0 modulation, particularly at air-tissue interfaces |

The most significant effects include spin-history artifacts, where motion alters the excitation history of spins, leading to signal loss or enhancement that cannot be corrected through image registration [9]. Additionally, motion of anatomical structures relative to the typically inhomogeneous receiver coil sensitivities produces position-dependent signal weighting that is particularly problematic for parallel imaging and simultaneous multi-slice acquisitions, where it can result in oscillating levels of residual aliasing or g-factor penalty variations [9]. Perhaps most challenging are the magnetic field inhomogeneity alterations caused by head motion, as the magnetic field distribution within the brain is determined not only by the head itself but by substantial contributions from the shoulders, chest, and lungs [9]. Rotation of the head causes these field deviations to change in complex ways that do not simply move in synchrony with the brain [9].

Experimental Protocols for Motion Mitigation

Protocol: Real-Time Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) for Fetal fMRI

This protocol outlines the implementation of a U-Net-based segmentation and registration pipeline for prospective motion correction in fetal fMRI, achieving a remarkable one-TR (repetition time) latency that enables motion data from one repetition to guide adjustments in subsequent frames [1].

Application Notes: This approach is particularly valuable for unpredictable fetal motion that traditionally distorts images and reduces data reliability in developmental studies. The method significantly enhances data quality for studying early functional brain development.

Materials and Equipment:

- Siemens MRI scanner (protocol adaptable to other platforms)

- Real-time image reconstruction pipeline

- U-Net convolutional neural network architecture

- High-performance computing unit for rapid segmentation

- Prospective motion correction pulse sequence

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Real-Time Image Acquisition: Acquire single-shot EPI images with minimal TR.

- U-Net-Based Segmentation: Immediately process each volume through a pre-trained U-Net to segment fetal brain tissue.

- Rigid Registration: Calculate transformation parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) between current and reference segmentations.

- Slice Position Adjustment: Apply transformation to adjust the orientation and position of subsequent acquisition slices.

- Continuous Monitoring: Repeat process for each TR, maintaining a closed-loop correction system.

Quality Control: Monitor temporal SNR (tSNR) and Dice similarity index for performance validation. The published implementation achieved a 23% increase in tSNR and 22% increase in Dice similarity compared to uncorrected data [1].

Protocol: Real-Time Motion Feedback Using FIRMM Software

This protocol details the implementation of Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring (FIRMM) to provide real-time motion estimates during scanning, enabling technicians to intervene when excessive motion occurs and improving the amount of usable data acquired.

Application Notes: Particularly effective for infant imaging and populations with limited ability to remain still, this approach has demonstrated significant improvements in acquiring high-quality, low-motion fMRI data without requiring sequence modifications [7].

Materials and Equipment:

- MRI scanner with real-time image reconstruction capability

- FIRMM software installation

- Visual feedback display for technologist

- Optional participant feedback display

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Configuration: Install FIRMM software and connect to scanner's image reconstruction pipeline.

- Real-Time Motion Calculation: Compute framewise displacement (FD) for each volume immediately after reconstruction using the six rigid-body realignment parameters.

- Technologist Alerting: Display real-time FD values and trends to the MR technologist.

- Participant Feedback (Optional): Provide visual motion feedback to participants via in-bore display (e.g., color-coded cross: white < 0.2 mm, yellow 0.2-0.3 mm, red ≥ 0.3 mm) [6].

- Between-Run Feedback: Show participants their motion performance after each run to encourage improvement in subsequent runs.

- Scan Continuation/Termination Decision: Use motion metrics to determine whether to continue, repeat, or abort scanning runs.

Quality Control: In infant imaging, this approach significantly increased the amount of usable fMRI data (FD ≤ 0.2 mm) acquired per infant [7]. In task-based fMRI with adults, it reduced average FD from 0.347 mm to 0.282 mm [6].

Protocol: Electromagnetic Tracking for Prospective Motion Correction

This protocol implements electromagnetic (EMF) tracking using head-mounted coils for high-accuracy prospective motion correction, achieving sub-millimeter and sub-degree precision compatible with standard MRI hardware [10].

Application Notes: This hardware-based approach provides robust six degrees-of-freedom motion tracking without the latency of image-based registration, making it suitable for applications requiring the highest precision motion correction.

Materials and Equipment:

- Standard MRI scanner without hardware modification

- Custom five-coil array arranged on a cube mount

- Head coil attachment apparatus

- Voltage measurement system for induced signals

- Calibration matrix for pose estimation

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Coil Array Mounting: Secure the five-coil array to the participant's head using a custom attachment.

- System Calibration: Establish calibration matrix relating induced voltages to head position and orientation.

- Real-Time Voltage Measurement: Measure induced voltages in coils during application of time-varying magnetic field gradients.

- Pose Estimation: Invert calibration matrix to compute real-time position and orientation from voltage measurements.

- Prospective Sequence Adjustment: Feed pose information to pulse sequence for real-time adjustment of slice orientation and position.

- Noise Robustness Verification: Validate tracking stability with added noise voltage up to 20 μV.

Quality Control: The method maintains accuracy of approximately 0.3 mm and 0.05° even in noisy conditions, providing robust motion tracking for high-precision applications [10].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for fMRI Motion Mitigation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time Monitoring Software | FIRMM (Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring) | Provides real-time motion estimates to technologists during acquisition; improves scanning efficiency | Requires connection to scanner reconstruction pipeline; validated in infant and adult populations [7] |

| Prospective Motion Correction Systems | Optical tracking (e.g., Markerless systems), EMF-based tracking, PMC sequences | Tracks head motion and adjusts slice acquisition in real-time; minimizes spin-history effects | EMF tracking offers high accuracy (<3 mm, <0.05°); markerless systems avoid facial markers [10] [3] |

| AI-Driven Motion Correction | U-Net segmentation, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Deep learning models | Enables real-time segmentation for PMC; removes artifacts in post-processing | U-Net achieves one-TR latency; GANs can correct non-linear distortions but risk visual artifacts [1] [11] |

| Retrospective Correction Algorithms | ABCD-BIDS pipeline, Motion censoring (e.g., FD < 0.2 mm), Global signal regression | Removes motion artifacts during post-processing; reduces spurious correlations | ABCD-BIDS reduces motion-related variance by 69% vs. minimal processing; censoring reduces overestimation to 2% of traits [8] |

| Data Transfer Solutions | Direct TCP/IP-based export | Enables real-time fMRI by minimizing data transfer delays | Reduces transfer time to ~30ms vs. 300ms for indirect DICOM export; crucial for real-time applications [12] |

Motion artifacts in fMRI present a multifaceted challenge with consequences extending from false scientific conclusions to compromised drug trial outcomes. The systematic nature of motion-induced signal changes means that simply excluding high-motion participants may introduce selection bias, particularly for studies involving clinical populations or developmental disorders where motion is inherently more prevalent. The integration of prospective motion correction methods, real-time monitoring, and robust analytical frameworks represents a essential strategy for preserving data integrity.

Future developments in motion mitigation will likely focus on the integration of artificial intelligence with real-time tracking systems, improved data transfer protocols for true real-time processing, and the standardization of motion reporting metrics across studies. Particularly promising are deep learning approaches, especially generative models, which show significant potential for improving MRI image quality by effectively addressing motion artifacts, though challenges of generalizability and reliance on paired training data remain [11]. For drug trials and other high-stakes fMRI applications, implementing the rigorous protocols outlined in this document is not merely a technical consideration but a fundamental requirement for generating valid, reproducible results that can reliably inform scientific understanding and clinical development.

The Paradigm Shift from Post-Hoc Correction to Real-Time Intervention

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has long been plagued by the confounding effects of head motion, which introduces noise and spurious signals that can compromise data integrity and lead to false positives in brain activation maps [8] [13]. For decades, the neuroimaging community has primarily relied on post-hoc correction algorithms implemented in software packages such as FSL, SPM, and AFNI to mitigate these effects after data acquisition [14] [15]. However, these retrospective approaches suffer from fundamental limitations, including their inability to correct for intra-volume motion and the inevitable signal interpolation required during image realignment [16] [13].

The paradigm is now shifting from retrospective correction to prospective, real-time intervention. This transition is driven by technological advances in real-time tracking systems, accelerated image processing, and sophisticated feedback mechanisms that actively prevent motion artifacts from occurring during data acquisition [16] [1] [7]. This application note documents this transformative shift, providing quantitative evidence of its benefits and detailed protocols for implementation across diverse research populations.

Quantitative Comparison of Motion Correction Approaches

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Motion Correction Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Key Metrics | Performance Data | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective (FSL, SPM) [14] [13] | Post-acquisition image registration | • Activation cluster size• Maximum t-value | • Up to 20% improvement in activation magnitude• Up to 100% increase in cluster size | • Cannot correct intra-volume motion• Interpolation-induced blurring• Spin history effects |

| Prospective MS-PACE [16] | Real-time slice-to-volume registration | • Temporal SNR• Mean voxel displacement• Spurious activations | • General increase in tSNR• Significant reduction in voxel displacement• Reduced artefactual activations | • Reduced voxels in registration |

| FIRMM Feedback [7] [6] | Real-time motion monitoring with visual feedback | • Framewise displacement (FD)• Usable data (FD ≤ 0.2 mm) | • 23% increase in usable fMRI data in infants• 19% reduction in average FD during tasks | • Cognitive load during tasks• Effectiveness varies by population |

| PRAMMO [13] | Active marker tracking with slice-plane update | • Statistical power• BOLD signal variance | • Substantial increase in activated region size and significance• Reduced variance without decreasing BOLD signal | • Requires external hardware• Marker attachment complexity |

Table 2: Real-Time Motion Correction Software Solutions

| Software/System | Tracking Method | Update Rate | Target Population | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-PACE [16] | Image-based (2D EPI slices to reference volume) | Sub-TR | General (7T fMRI) | • No external hardware• Compatible with parallel imaging |

| FIRMM [7] [6] | Image-based realignment parameters | Per volume | Infants, adults, clinical populations | • Real-time visual feedback• No sequence modification |

| PRAMMO [13] | Active RF markers | Slice-by-slice (25 ms update) | General research | • High precision (0.01 mm)• Corrects intra-volume motion |

| Accelerated vNav [17] | GRAPPA-accelerated 3D EPI navigators | 242-1302 ms (depending on resolution) | Patients with metal implants, general | • Whole-brain ΔB₀ field mapping• Combined motion and shim correction |

Experimental Protocols for Real-Time Motion Intervention

Protocol 1: MS-PACE Implementation for Ultra-High Field fMRI

Application: Task-based fMRI studies at 7T where motion sensitivity is elevated and BOLD signal gains are paramount [16].

Equipment Requirements:

- 7T MRI scanner with real-time sequence modification capabilities

- Single-shot EPI sequence with parallel imaging (GRAPPA)

- Reference volume acquisition protocol

Procedure:

- Reference Phase: Acquire a full volume of 2D EPI navigator slices at the sequence beginning to serve as the motion-free reference.

- Tracking Phase: During the main EPI acquisition, continuously acquire a subset of equidistantly spaced 2D EPI navigator slices.

- Registration Phase: Perform real-time rigid-body registration (3 translations, 3 rotations) of the navigator slices to the reference volume using a similarity metric (e.g., normalized mutual information).

- Update Phase: Feed the calculated transformation parameters back to the pulse sequence to prospectively adjust the scan plane for subsequent slice acquisitions.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 throughout the EPI time series, providing continuous sub-TR motion correction.

Validation Metrics:

- Quantify mean voxel displacement relative to reference

- Calculate temporal SNR across the time series

- Compare activation maps with and without MS-PACE

Protocol 2: FIRMM-Enhanced Data Acquisition in Challenging Populations

Application: Resting-state or task-based fMRI in infants, children, older adults, or clinical populations with elevated motion characteristics [7] [6].

Equipment Requirements:

- MRI scanner with real-time data transfer capability

- FIRMM (Framewise Integrated Real-Time MRI Monitoring) software installation

- Visual feedback display system visible to participants

Procedure:

- Setup: Install FIRMM software and configure for real-time calculation of framewise displacement (FD) from incoming DICOM images.

- Participant Instructions: Provide clear instructions to participants about the feedback system:

- "You will see a white fixation cross that will change color based on your movement."

- "Try to keep the cross white by holding as still as possible."

- Threshold Configuration: Set FD thresholds for feedback display:

- White cross: FD < 0.2 mm

- Yellow cross: FD 0.2 mm to < 0.3 mm

- Red cross: FD ≥ 0.3 mm

- Real-Time Monitoring: During acquisition, FIRMM calculates FD for each volume and updates the visual display accordingly.

- Between-Run Feedback: After each run, show participants a Head Motion Report with their performance score (0-100%) and motion trace over time.

- Technician Monitoring: Allow technicians to monitor motion levels in real-time and provide additional verbal encouragement when needed.

Validation Metrics:

- Compare average framewise displacement with and without FIRMM

- Quantify the amount of usable data (FD ≤ 0.2 mm) per participant

- Measure scanning efficiency (amount of high-quality data acquired per unit time)

Protocol 3: Active Marker Prospective Correction (PRAMMO) for High-Precision Studies

Application: Studies requiring maximum BOLD sensitivity and statistical power, particularly those investigating subtle effects or using complex paradigms [13].

Equipment Requirements:

- MRI-compatible active marker system with integrated headband

- Multi-channel receiver capability for simultaneous marker tracking

- Pulse sequence with integrated tracking and update modules

Procedure:

- Marker Placement: Secure the headband with three active RF markers firmly to the participant's head, ensuring minimal movement relative to the skull.

- Reference Measurement: Acquire initial marker positions at the scan beginning to establish a reference position.

- Integrated Tracking: Implement a track-and-update module before each EPI slice acquisition:

- Tracking: Acquire rapid 1D projections to measure current marker positions (≈25 ms)

- Calculation: Compute 6-degree-of-freedom transform relative to reference

- Update: Adjust scan plane orientation and position for the next slice

- Continuous Operation: Maintain the track-update cycle throughout the entire functional time series.

- Data Logging: Record all motion parameters for offline analysis and quality assessment.

Validation Metrics:

- Compare group-level statistical power (effect sizes) with and without PRAMMO

- Quantify the variance reduction in BOLD signal

- Measure the extent and significance of activated regions across experimental conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Real-Time Motion Intervention

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time fMRI Software [7] [6] | Provides motion metrics and feedback | FIRMM software, custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Integration with scanner, computation speed |

| Optical Motion Tracking Systems | External head motion tracking | Vendor-specific systems (e.g., Philips, Siemens) | Marker attachment, line-of-sight requirements |

| Active Marker Systems [13] | RF-based tracking without line-of-sight limitation | PRAMMO system with active RF markers | Hardware compatibility, headband design |

| Visual Feedback Display [6] | Presents real-time motion feedback to participants | MRI-compatible display systems | Simple, intuitive display design |

| 3D EPI Navigators [17] | Volumetric motion and B₀ field mapping | GRAPPA-accelerated dual-echo EPI | Trade-off between resolution and acquisition time |

| High-Performance Computing Resources | Real-time image processing | GPU acceleration, fast data transfer | Latency requirements for real-time feedback |

Workflow Visualization

The paradigm shift from post-hoc correction to real-time intervention represents a fundamental advancement in fMRI methodology that addresses long-standing limitations of retrospective approaches. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that techniques such as MS-PACE, FIRMM, and PRAMMO significantly improve data quality through increased temporal SNR, reduced voxel displacement, and enhanced statistical power in group-level analyses [16] [7] [13].

The implementation of real-time motion intervention requires careful consideration of experimental needs, participant populations, and available resources. For ultra-high field studies where motion sensitivity is paramount, image-based methods like MS-PACE provide hardware-free correction integrated directly into the acquisition sequence [16]. For challenging populations such as infants or clinical cohorts, FIRMM's feedback approach leverages behavioral intervention to reduce motion at its source [7] [6]. For studies demanding the highest precision, marker-based systems like PRAMMO offer slice-by-slice correction that addresses both inter- and intra-volume motion [13].

As fMRI continues to evolve toward more sophisticated applications—including clinical assessment, drug development, and individualized medicine—the adoption of real-time motion intervention will be essential for ensuring data quality, reproducibility, and valid scientific inference. The protocols and implementations described herein provide researchers with practical pathways to integrate these advanced methodologies into their experimental designs.

The development of new central nervous system (CNS) therapeutics is hampered by high failure rates, often due to the inability to demonstrate target engagement or predict clinical efficacy in early-phase trials. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) presents a powerful tool for quantifying brain activity, offering potential biomarkers for drug development. However, the utility of fMRI-derived biomarkers is critically dependent on their robustness, with head motion representing a significant source of noise and bias. This application note details how advancements in real-time fMRI motion tracking and correction software are creating a new generation of reliable, regulatory-grade biomarkers capable of de-risking the drug development pathway for FDA and EMA submissions.

The Motion Problem: A Critical Barrier to Robust fMRI Biomarkers

Head motion during fMRI acquisition degrades data quality and introduces systematic biases that can lead to false positives or negatives, fundamentally undermining biomarker validity. This is particularly critical in clinical populations, including neurological patients who may move more, and in longitudinal studies where motion may correlate with treatment effects or disease progression [18]. Even small, sub-millimeter movements can create spurious but structured patterns that mimic genuine brain connectivity or activation [18].

Table 1: Impact of Head Motion on fMRI Data Quality and Biomarker Validity

| Aspect of Impact | Consequence for Data Quality | Risk to Biomarker Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Decreased, making true effects harder to detect [1]. | Reduced power to detect drug-induced changes, requiring larger sample sizes. |

| Activation Estimates | Can cause false activations or reduce sensitivity to true activation [18]. | Misleading conclusions about brain regions affected by a therapeutic. |

| Functional Connectivity | Introduces spurious correlations, particularly in nearby brain regions [18]. | False characterization of a drug's effect on brain networks. |

| Group Differences | Can create artifactual group differences if motion varies between groups (e.g., patients vs. controls) [18]. | Inability to distinguish confound from true treatment or disease effects. |

Experimental Protocols for Motion-Robust fMRI in Clinical Trials

Implementing standardized protocols is essential for ensuring the consistency and quality of fMRI data across multi-site clinical trials. The following protocols address motion mitigation through study design, acquisition, and processing.

Protocol: Participant Preparation and In-Scanner Motion Reduction

Objective: To minimize the occurrence of head motion at its source through participant engagement and optimized study design.

Materials:

- MR-compatible response collection device (e.g., ResponseGrips) [19]

- Stimulus presentation and synchronization system (e.g., SyncBox, nordicAktiva) [19]

- Mock scanner for training

Methodology:

- Mock Scanner Training: Conduct a mock scanner session prior to the actual scan to acclimatize participants to the environment and tasks.

- Paradigm Design: Utilize software (e.g., nordicAktiva, E-Prime, Presentation) to design and present tasks [20] [19]. The timing of stimulus presentation must be automatically synchronized with image acquisition using a device like the SyncBox to ensure validity [19].

- Scheduled Breaks: Split fMRI data acquisition into multiple, shorter sessions or blocks interspersed with inside-scanner breaks. Evidence shows this significantly reduces head motion in both children and adults [21].

- Real-Time Performance Monitoring: Use MR-compatible devices like ResponseGrips to collect participant responses, providing a measure of task engagement and performance quality during the scan [19].

Protocol: Prospective Motion Correction (PMC) during Acquisition

Objective: To correct for head motion in real-time during image acquisition, preventing the occurrence of motion artifacts.

Materials:

- Real-time motion tracking system (e.g., utilizing a U-Net-based segmentation and rigid registration pipeline) [1]

Methodology:

- Real-Time Tracking: Implement a PMC system that continuously tracks the position of the head in the scanner. A recent study demonstrated a system that performs real-time fetal head segmentation and motion tracking with a latency of one repetition time (TR) [1].

- Slice Position Adjustment: The estimated motion parameters are fed back to the scanner's pulse sequence to prospectively adjust the slice positioning for the subsequent acquisition, keeping the imaging volume locked to the brain [1].

- Quality Metrics: Following a PMC-enabled scan, calculate quality metrics such as the temporal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (tSNR) and the Dice similarity index to quantify the improvement in data quality. PMC has been shown to increase tSNR by 23% and the Dice index by 22% [1].

Protocol: Retrospective Motion Correction and Analysis

Objective: To mitigate the effects of residual head motion during data processing and to incorporate kinematic data for refined analysis.

Materials:

- Processing software (e.g., FSL, SPM, AFNI) [20]

- Motion capture system for kinematic assessment (for motor task studies) [22]

Methodology:

- Realignment: Estimate head motion parameters (3 translations, 3 rotations) by aligning each volume to a reference volume in the time series using tools like MCFLIRT in FSL [20].

- Nuisance Regression: Incorporate the motion parameters as nuisance regressors in the General Linear Model (GLM). Evidence suggests that a model with 6 motion parameters often provides the best trade-off, outperishing models with 24 parameters [18].

- Motion Outlier Correction: Identify volumes with excessive motion (outliers) using metrics like Framewise Displacement (FD) or DVARS. Apply scrubbing (adding regressors for outlier volumes) or volume interpolation to censor or correct these volumes. Studies indicate that volume interpolation can be a superior method for correcting motion outliers in task-based fMRI [18].

- Cortico-Kinematic Integration (for motor studies): In studies of motor function, statistically couple kinematic data (e.g., movement smoothness, compensation) with fMRI activity using regression or correlation analyses. This links brain activity to quantitative measures of movement quality, crucial for distinguishing recovery from compensation in conditions like stroke [22].

Software Solutions for Motion Management and Biomarker Analysis

A range of software tools is available for processing fMRI data and conducting meta-analyses to establish normative biomarkers. The choice of software depends on the specific analysis needs.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for fMRI Processing and Meta-Analysis

| Software Package | Primary Function | Application in Biomarker Development | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainEffeX | Web app for exploring fMRI effect sizes [23]. | Informs power analysis and sample size calculation for clinical trials by providing "typical" effect sizes from large datasets [23]. | Provides voxel-wise and multivariate effect size estimates (Cohen's d, R²) for brain-behavior, task, and group analyses [23]. |

| FSL | A comprehensive library of fMRI analysis tools [20]. | Used for model-based task analysis (FEAT), motion correction (MCFLIRT), and tissue segmentation (BET, FAST) [20]. | Widely used, open-source, includes tools for diffusion tractography and perfusion analysis [20]. |

| SPM | Statistical Parametric Mapping for voxel-level analysis [20]. | Employs the General Linear Model (GLM) for analyzing task-based and resting-state fMRI data [20]. | A historically dominant, MATLAB-based package with extensive features for processing, analysis, and display [20]. |

| AFNI | Analysis of Functional NeuroImages [20]. | Suite of C-based programs for processing, analyzing, and displaying fMRI data [20]. | Known for its flexibility and extensive set of command-line tools. |

| GingerALE | Coordinate-based meta-analysis (CBMA) [24]. | Identifies consistent regions of activation across published studies to define robust biomarker targets for a given cognitive or drug-induced state. | The most frequently used CBMA software (49.6% of papers); uses Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) algorithm [24]. |

| SDM-PSI | Seed-based d Mapping with Permutation of Subject Images [24]. | A hybrid meta-analysis tool that can pool data from studies with only peak coordinates and those with full statistical maps. | The second most popular meta-analysis software (27.4% of papers); supports both CBMA and image-based meta-analysis (IBMA) [24]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for fMRI Motion Tracking and Correction Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Presentation & Sync | Presents paradigms and synchronizes with scanner acquisition. | nordicAktiva software with SyncBox ensures precise timing for task-based fMRI, critical for GLM analysis [19]. |

| Response Collection Device | Records participant responses and performance. | ResponseGrips allow for measurement of task engagement and performance quality during motor or cognitive tasks [19]. |

| Motion Capture System | Quantifies movement kinematics outside the scanner. | In post-stroke motor studies, couples movement quality (smoothness) with brain activity to interpret plasticity [22]. |

| Real-Time Processing Platform | Enables real-time fMRI and prospective motion correction. | Custom pipelines for real-time head tracking and slice repositioning to prevent motion artifacts [1]. |

| Post-Processing Software | Performs retrospective motion correction and statistical analysis. | FSL's MCFLIRT for realignment; regression of motion parameters in SPM or FSL's FEAT [18] [20]. |

Integration into the Drug Development Pipeline

For a biomarker to be considered in regulatory submissions, it must demonstrate analytical validity (reliability and accuracy), clinical validity (ability to accurately reflect a clinical state or outcome), and clinical utility (ability to improve patient outcomes). Real-time motion tracking and the standardized protocols described herein directly underpin analytical validity by ensuring that the measured fMRI signal is neurally derived and not an artifact of motion.

The workflow below illustrates how motion-corrected fMRI integrates into a typical drug development pathway, from discovery to regulatory submission.

The integration of real-time fMRI motion tracking and rigorous correction software is transforming fMRI from a purely research tool into a source of robust, regulatory-grade biomarkers. By systematically addressing the primary confound of head motion through prospective technologies, optimized experimental protocols, and standardized processing pipelines, researchers can generate high-quality, reliable data. This enhanced data integrity strengthens the evidence for target engagement and drug efficacy, providing the FDA and EMA with the confidence needed to accept fMRI biomarkers as objective endpoints in clinical trials, ultimately accelerating the development of new CNS therapeutics.

Implementing Real-Time fMRI Motion Tracking: Software, Workflows, and Applications

Real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging (rt-fMRI) represents a significant methodological advancement in neuroimaging, enabling a range of novel applications including neurofeedback, brain-computer interfaces, real-time quality assurance, and adaptive experimental control [25]. The software architecture of these systems presents unique computational and engineering challenges, as they must process complex imaging data within the stringent time constraints of the repetition time (TR)—typically on the order of seconds [12]. This document outlines the core architectural components, data handling methodologies, and implementation frameworks that constitute modern rt-fMRI systems, with particular emphasis on their application within motion tracking software research.

The fundamental shift from traditional offline fMRI analysis to real-time processing requires architectures that guarantee reliable data transfer, rapid preprocessing, and immediate analysis—all while maintaining temporal synchronization with the ongoing acquisition and experimental paradigm [25] [26]. The architectural patterns discussed herein provide the foundation for systems that can transform the MRI scanner from a passive measurement device into an interactive tool for neuroscience research and clinical application.

Core Architectural Components of Real-Time fMRI Systems

The software architecture of rt-fMRI systems is typically organized into a modular pipeline where data flows sequentially from acquisition to final application. The design is driven by the need to minimize latency at each stage.

Data Acquisition and Transfer Layer

This initial component is responsible for obtaining image data from the scanner and delivering it to processing units. Two predominant architectural patterns exist for this transfer:

- Direct TCP/IP Streaming: This method establishes a direct socket connection between the scanner reconstruction computer and the external processing machine. Data is sent immediately after reconstruction, often using custom code inserted into the scanner's image reconstruction pipeline (e.g., an ICE functor for Siemens scanners) [12]. This approach minimizes latency.

- File-Based Monitoring ("Indirect" Transfer): This method involves monitoring a designated directory on the scanner host for new image files (e.g., DICOM mosaics). A separate process detects new files, reads them, and forwards the data [27] [28]. This can introduce more variable latency compared to direct streaming.

A comparative study of these methods demonstrated a significant performance difference, with direct TCP/IP connection (mean = 89.5 ms ± 76.9 ms) drastically outperforming indirect file-based transfer (mean = 513.9 ms ± 171.7 ms) on a 3T Siemens scanner [12]. This makes the direct method critical for applications requiring low-latency feedback.

Preprocessing and Analysis Module

Once data is acquired, it undergoes real-time preprocessing. A key feature of robust architectures is the separation of this module from the acquisition layer, allowing the preprocessing to be environment-agnostic [25]. Common operations include:

- Realignment/Motion Correction: Correcting for head motion using algorithms like SPM's realignment. This is a cornerstone of motion tracking software, providing estimates of subject movement in real time [27] [28].

- Slice Timing Correction: Accounting for the fact that different slices within a volume are acquired at different times.

- Spatial Normalization: Warping individual brain images to a standard template space (e.g., MNI). This is essential for subject-independent classification, as implemented in toolboxes like MANAS [29].

- Temporal Filtering: Applying high-pass or band-pass filters to the time series data.

These preprocessing steps are computationally intensive. The MANAS toolbox, for instance, requires approximately 0.7–1.2 seconds to process a single whole-brain volume, making it suitable for paradigms with a TR > 1 second [29].

Real-Time Classification and Feature Extraction Engine

This component translates preprocessed data into a meaningful signal for feedback or analysis. For neurofeedback and BCI applications, this often involves multivariate pattern classification.

- Subject-Dependent Classification: A classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine - SVM) is trained on data from the same individual to distinguish between specific brain states. This offers high within-subject accuracy but requires a prior training session [29].

- Subject-Independent Classification (SIC): A classifier is pre-trained on a group of individuals and applied to new, unseen subjects. This eliminates the need for subject-specific training and is particularly valuable in clinical contexts where training data may be unavailable or derived from abnormal brain activity. SIC requires real-time spatial normalization to a standard brain space [29].

Toolboxes such as MANAS integrate both approaches, using libraries like LIBSVM or SVMlight, and can perform effect mapping to generate spatial maps of features driving the classification [29].

Integration and Communication Interface

A critical layer manages communication between the rt-fMRI system and other hardware/software components. This is often implemented using a standardized messaging framework.

- TCP/IP Sockets & ZeroMQ: Used for reliable, low-latency inter-process communication, even across different physical machines [25].

- FieldTrip Buffer: A network-transparent platform that allows multiple client applications to read and write data and events to a central server, simplifying the construction of complex real-time processing pipelines [27].

- API for External Devices: Provides an interface for the system to output results to stimulus presentation software (e.g., Presentation, E-Prime), neurofeedback displays, or even to control external devices in a BCI setup [25] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow between these core components in a typical rt-fMRI system.

Quantitative Performance Data and System Comparisons

The effectiveness of an rt-fMRI system is quantified by its latency, throughput, and classification accuracy. The tables below summarize key performance metrics and architectural features from published systems and studies.

Table 1: Measured Latency of Data Transfer Methods in Real-Time fMRI

| Transfer Method | Scanner Type | Mean Transfer Time (ms) | Standard Deviation (ms) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct TCP/IP Connection [12] | 3T Siemens Prisma | 89.5 | 76.9 | Low latency, low jitter |

| Direct TCP/IP Connection [12] | 7T Siemens Magnetom | 29.8 | 18.3 | Very low latency |

| Indirect File-Based (SMB) [12] | 3T Siemens Prisma | 513.9 | 171.7 | High latency, high jitter |

| Indirect File-Based (SMB) [12] | 7T Siemens Magnetom | 301.0 | 87.1 | Medium latency |

Table 2: Architectural Features and Performance of Real-Time fMRI Toolboxes

| Software / Toolbox | Primary Language | Key Architectural Feature | Reported Processing Time | Supported Classifiers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyneal [25] | Python | Modular; separate Pyneal Scanner and Pyneal processes | Not Specified | ROI-based analysis, Custom Python scripts |

| MANAS [29] | MATLAB | Integrated SPM pre-processing; Subject-Independent Classification | 0.7 - 1.2 s per volume | SVM (LIBSVM, SVMlight) |

| CNI rtfmri [28] | Python | ScannerInterface class; FIFO queue for volumes | Not Specified | Real-time motion estimation |

| FieldTrip [27] | C++ / MATLAB | Buffer server for client-server pipeline | Not Specified | General-purpose, supports custom analysis |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for System Validation

For researchers implementing these architectures, validating system performance and conducting experiments requires standardized protocols. The following sections detail key methodologies.

Protocol for Latency and Data Transfer Reliability Testing

Objective: To quantitatively measure the latency and jitter of the data transfer method in an rt-fMRI setup.

Materials:

- MRI scanner with sequence modified for real-time export (e.g., ICE functor for direct transfer).

- Real-time analysis computer with receiving software (e.g., Turbo-BrainVoyager, custom script).

- Method for precise time-stamping (e.g., scanner trigger pulse, network packet capture).

Procedure:

- Synchronize Clocks: Ensure the scanner host and the analysis computer have synchronized system clocks.

- Log Trigger Times: For each volume (time point

t), record the precise time of the acquisition trigger pulse (T_trigger_t). - Log Receive Times: On the analysis computer, for each volume

t, record the precise time when the complete volume data is received and ready for processing (T_receive_t). - Calculate Transfer Time: Compute the pure data transfer time for volume

tas:Transfer_Time_t = T_receive_t - T_trigger_t. Some implementations use the trigger of volumet+1as a reference to account for the reconstruction time internal to the scanner [12]. - Data Analysis: Over a typical run (e.g., 100 volumes), calculate the mean, standard deviation (jitter), and maximum value of the

Transfer_Time. Compare different transfer methods (direct vs. indirect) under identical scanning parameters.

Protocol for Online Subject-Independent Classification

Objective: To train a classifier on a group of subjects and apply it in real-time to a new subject for brain state decoding or neurofeedback.

Materials:

- MANAS toolbox or similar software with SIC capability [29].

- Pre-trained SVM classifier model (e.g., trained on healthy subjects performing a motor task).

- Target patient or subject population for feedback.

Procedure:

- Classifier Training (Offline):

- Acquire fMRI data from a cohort of healthy subjects performing the target task (e.g., motor imagery) and a control task.

- Preprocess the data (realignment, normalization, smoothing).

- Extract feature vectors (e.g., voxel intensities from a mask).

- Train a multi-class SVM classifier and save the model.

- Real-Time Execution:

- Configure the MANAS toolbox for real-time operation, specifying the pre-trained model and necessary preprocessing steps (including real-time normalization to MNI space).

- For the new subject, initiate the real-time fMRI scan.

- For each incoming volume, MANAS will automatically: a. Preprocess the image (realignment, normalization). b. Extract the feature vector based on the model's mask. c. Classify the brain state using the pre-trained SVM. d. Output the classification result (e.g., "Motor Imagery" or "Rest") and a corresponding feedback value.

- Validation: Compare the online classification accuracy with offline analyses of the same data. For neurofeedback, assess whether subjects can learn to modulate their brain activity based on the classifier's output.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of an rt-fMRI system relies on a combination of software, hardware, and data resources. The following table catalogs key components.

Table 3: Essential Components for a Real-Time fMRI Research Setup

| Item Name | Category | Function / Purpose | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyneal Toolkit | Software | Flexible, open-source platform for building custom rt-fMRI pipelines [25] | https://github.com/jeffmacinnes/pyneal |

| FieldTrip Buffer | Software | Network-transparent server for streaming data and events in real-time pipelines [27] | https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/ |

| MANAS Toolbox | Software | Provides both subject-dependent and subject-independent real-time fMRI classification [29] | Contact original authors |

| CNI rtfmri | Software | Python-based real-time interface and motion analysis for GE scanners [28] | https://github.com/cni/rtfmri |

| SVM Libraries | Software | Core engine for multivariate pattern classification. | LIBSVM, SVMlight [29] |

| Real-Time Export ICE Functor | Scanner Software | Enables direct, low-latency TCP/IP data streaming from Siemens scanners [12] | Custom C++ code for Siemens ICE |

| Analog-to-Digital (A/D) Converter | Hardware | Acquires physiological signals (cardiac, respiratory, GSR) for real-time monitoring and noise regression [26] | Measurement Computing USB-1280FS |

| Physiological Monitoring Kit | Hardware | Records peripheral data that influences BOLD signals. | Biopac respiratory belt (TSD201) & pulse oximeter (TSD123A) [26] |

| Standard Brain Template | Data | Enables spatial normalization for subject-independent analysis. | Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template [29] |

| Pre-trained Classifier Model | Data | The trained model (e.g., SVM) used for Subject-Independent Classification. | Created from healthy cohort data [29] |

The architectural patterns and components described provide a roadmap for developing robust real-time fMRI systems. The choice of specific tools and protocols depends on the experimental goals, whether they are low-latency neurofeedback, real-time quality assurance, or adaptive brain-computer interfaces. As the field evolves, standardization of data export interfaces and continued development of open-source toolboxes will be crucial for advancing both research and clinical applications.

Framewise Integrated Real-time MRI Monitoring (FIRMM) is an advanced software suite designed to address one of the most significant challenges in brain MRI data acquisition: head motion. Motion artifacts systematically distort both clinical and research MRI data, potentially biasing findings from structural and functional brain studies [30]. FIRMM provides real-time motion analytics during brain MRI acquisition, enabling scanner operators to monitor data quality as it is being collected. This innovative approach represents a paradigm shift from traditional post-hoc quality assessment to proactive quality assurance, allowing technologists to scan each subject until the desired amount of low-movement data has been collected [30].

The software is particularly valuable for research populations where motion control is challenging, such as pediatric, elderly, or patient cohorts with neurological or psychiatric conditions. By providing immediate feedback on motion metrics, FIRMM empowers MRI technologists to make informed decisions during scanning sessions, potentially rescuing data that might otherwise be compromised by excessive motion [7]. This capability is crucial for maintaining statistical power in research studies and ensuring diagnostic quality in clinical settings.

Technical Specifications and Operational Mechanisms

Core Architecture and Processing Pipeline

FIRMM is built on a sophisticated software architecture that integrates multiple specialized components for optimal performance. The system employs a Django web application frontend for user interaction and a compiled MATLAB binary backend (R2016b) for computational processing, requiring only an included MATLAB compiler runtime to operate [30]. This design ensures robust performance without demanding full MATLAB licenses for each installation. The software utilizes shell scripts for image processing operations, with all critical dependencies containerized within a Docker image to guarantee consistency across different computing environments [30].

The operational workflow begins with DICOM images being transferred from the MRI scanner to a pre-designated folder monitored by FIRMM. On Siemens scanners, this is typically accomplished by selecting the 'send IMA' option in the ideacmdtool utility or using specialized MS-DOS batch scripts that add start/stop FIRMM buttons to the scanner operating system [30]. As each frame/volume of Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) data is acquired and reconstructed into DICOM format, FIRMM processes them sequentially through a job queuing system that maintains temporal acquisition order.

Motion Quantification Algorithm

FIRMM's core innovation lies in its accurate, real-time calculation of framewise displacement (FD), which represents the sum of absolute head movements in all six rigid body directions from frame to frame [30]. The software converts DICOM images into 4dfp format before performing realignment using the optimized crossrealign3d4dfp algorithm [30]. This algorithm has been specifically optimized for computational speed by disabling frame-to-frame image intensity normalization and preventing the writing out of realigned data—only the alignment parameters are preserved for FD calculation.

Unlike external motion tracking systems that use cameras or lasers—which poorly correlate with actual brain movement because they cannot distinguish facial/scalp movements from brain motion—FIRMM calculates FD directly from the imaging data itself [30]. This approach provides a more accurate representation of the motion artifacts that actually affect MRI data quality. The software also incorporates a predictive algorithm that accurately estimates the required additional scan time needed to capture sufficient quality data based on current motion patterns [31].

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications of FIRMM Software

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Frontend | Django web application | Visual display of motion metrics and plots |

| Backend | Compiled MATLAB binary | Core processing and FD calculation |

| Image Processing | Shell scripts with Docker container | Management of software dependencies |

| Alignment Algorithm | crossrealign3d4dfp | Rapid realignment of EPI data |

| Output Format | 4dfp | Optimized for processing efficiency |

| System Requirements | Docker-capable Linux (Ubuntu 14.04, CentOS 7) | Platform compatibility |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Efficiency and Cost-Benefit Analysis

FIRMM demonstrates substantial practical benefits in both research and clinical settings. Implementation of the software has been shown to reduce total brain MRI scan times and associated costs by 50% or more by eliminating unnecessary "buffer data" collection and enabling efficient "scanning-to-criterion" approaches [31] [30]. Detailed economic analyses reveal that healthcare facilities can save approximately $115,000 per scanner per year through optimized scanning protocols [32]. These savings stem from both reduced scan durations and decreased need for repeat sessions due to motion-corrupted data.

The software significantly improves operational efficiency, with studies reporting an estimated 55% time savings in MRI workflows [32]. This efficiency gain allows facilities to either accommodate more patients or allocate saved time to more complex cases. Additionally, FIRMM implementation has demonstrated a 25% reduction in unnecessary repeat scans, directly addressing one of the most resource-intensive challenges in neuroimaging [32]. This reduction not only improves operational metrics but also enhances patient satisfaction and comfort by minimizing prolonged or repeated scanning sessions.

Data Quality Improvements

FIRMM's impact on data quality is particularly evident in challenging patient populations. In pediatric cohorts, where frame censoring (removing data frames with FD values above specific thresholds) frequently excluded over 50% of resting-state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fcMRI) data, FIRMM-enabled scanning-to-criterion approaches have dramatically increased the yield of usable data [30]. This preservation of data integrity is crucial for maintaining statistical power in research studies and ensuring diagnostic quality in clinical applications.

A particularly compelling study compared average framewise displacement and the amount of usable fMRI data (FD ≤ 0.2 mm) in infants scanned with (n = 407) and without FIRMM (n = 295) [7]. Using a mixed-effects model, researchers found that the addition of FIRMM to state-of-the-art infant scanning protocols significantly increased the amount of usable fMRI data acquired per infant, demonstrating its value for both research and clinical neuroimaging in this challenging population [7].

Table 2: FIRMM Performance Metrics Across Studies

| Metric Category | Specific Measure | Performance Result | Study/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Impact | Cost savings per scanner | >$115,000 annually | Andre JB et al., 2015 [32] |

| Operational Efficiency | Time savings | 55% estimated reduction | Dosenbach, N.U.F. et al., 2017 [32] |

| Data Quality | Reduction in repeat scans | 25% decrease | Andre JB et al., 2015 [32] |

| Scan Duration | Overall reduction | 50% or more | NITRC Project Documentation [31] |

| Pediatric Imaging | Usable data increase | Significant improvement | PMC Study [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

System Installation and Configuration

FIRMM installation requires a Docker-capable Linux system, with confirmed operation on Ubuntu 14.04 and CentOS 7 operating systems [30]. Installation is accomplished via a downloadable shell script that retrieves and installs all FIRMM components. After installation, FIRMM is launched with a specialized shell script tailored to use a pre-built Docker image. The Turing Medical team typically leads users through the initial installation process and helps set protocol-specific parameters like motion thresholds and data quality goals required for specific studies [32].

For seamless integration with Siemens scanners, technicians can implement rapid DICOM transfer by selecting the 'send IMA' option in the ideacmdtool utility, which requires 'advanced user' mode access [30]. Alternatively, facilities can use a standalone MS-DOS batch script package that adds dedicated start 'FIRMM' and stop 'FIRMM' buttons to the scanner operating system, simplifying the workflow for technologists. This package can be downloaded alongside the main FIRMM software distribution.

Real-time Monitoring Protocol

During scanning sessions, FIRMM automatically plots motion traces and quality metrics when scanning begins [32]. The software provides a user-friendly, real-time feedback interface that can display the percentage of quality data frames, enabling some facilities to share this information directly with participants or display the FIRMM graphical user interface on the participant's screen in the scanner room for feedback and training purposes [31]. This transparency can enhance participant cooperation and reduce motion.

Technologists monitor the quality metrics in real-time, allowing them to adjust their approach based on the motion analytics [32]. If a participant exhibits periods of high motion, the technologist can pause acquisition and provide additional instructions or wait for a calmer state before continuing. Conversely, if the software indicates that sufficient high-quality data has been collected sooner than anticipated, the technologist can conclude the session, optimizing both time management and participant comfort.

Validation and Verification Procedures

The accuracy of FIRMM's motion quantification has been rigorously validated against standard offline, post-hoc processing streams [30]. Validation studies have utilized large rs-fcMRI datasets from diverse patient and control cohorts, totaling 1,134 scan sessions across Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Family History of Alcoholism (FHA), and control groups [30]. These studies confirmed that FIRMM's FD calculations are not only fast but also accurate when compared to conventional offline processing methods.

For institutions implementing FIRMM, establishing site-specific validation is recommended. This process involves running FIRMM concurrently with existing quality assurance protocols to verify concordance between FIRMM's real-time metrics and established offline quality measures. This parallel testing also helps technologists develop intuition for interpreting FIRMM metrics within the context of their specific patient populations and research objectives.

Application in Research and Clinical Contexts

Research Applications

FIRMM has proven particularly valuable in neurodevelopmental research involving challenging populations. In infant neuroimaging studies, where head motion during MRI acquisition is especially detrimental to data quality, FIRMM has enabled researchers to significantly increase the amount of usable fMRI data acquired per infant [7]. Even when infants are scanned during natural sleep, they commonly exhibit motion that causes data loss, making real-time monitoring especially valuable for these studies.

The software also supports sophisticated research designs that require specific amounts of high-quality data across multiple conditions or timepoints. By providing real-time feedback on data quality, researchers can ensure balanced datasets across participants and conditions, reducing potential biases introduced by differential data quality. Furthermore, FIRMM's ability to accurately predict the required scan time until sufficient quality data is collected enables more efficient scheduling and resource allocation in research settings [31].