Robust Brain Signatures for Behavioral Outcomes: A Framework for Statistical Validation in Clinical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and validating data-driven brain signatures that reliably predict behavioral outcomes.

Robust Brain Signatures for Behavioral Outcomes: A Framework for Statistical Validation in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and validating data-driven brain signatures that reliably predict behavioral outcomes. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the transition from theory-driven brain mapping to multivariate predictive models. The content covers foundational concepts, diverse methodological approaches from neuroimaging to biomimetic chromatography, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance. A core focus is on rigorous multi-cohort validation and comparative analysis against established models, highlighting how robust brain signatures can yield reliable, reproducible measures for understanding brain-behavior relationships and accelerating CNS drug discovery.

From Brain Mapping to Predictive Models: The Conceptual Foundation of Brain Signatures

Human neuroimaging research has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from mapping localized brain effects toward developing integrated, multivariate brain models of mental events [1]. This transition represents a reversal of the traditional scientific approach: where classic brain mapping analyzed brain-mind associations within isolated regions, modern brain models specify how to combine distributed brain measurements to predict the identity or intensity of a mental process [1]. This whitepaper examines the evolution of brain signatures from their conceptual foundations in neural representation theories to their current application as multivariate predictive tools for validating behavioral outcomes in research and drug development contexts.

The concept of "brain signatures" or neuromarkers refers to identifiable brain patterns that predict mental and behavioral outcomes across individuals [1]. These signatures provide a data-driven approach to understanding brain substrates of behavioral outcomes, offering the potential to maximally characterize the neurological foundations of specific cognitive functions and clinical conditions [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, validated brain signatures present unprecedented opportunities for quantifying treatment outcomes, identifying neurobiological subtypes, and developing personalized intervention strategies [3] [4].

Theoretical Foundations: From Localization to Distributed Representation

Historical Perspectives on Neural Representation

The theoretical underpinnings of brain signature research reflect a longstanding tension between two opposing perspectives on brain organization [5]:

The Localizationist View: Associates mental functions with specific, discrete brain regions, supported by univariate analyses of brain activity and psychological component models [5]. This perspective identified what are sometimes called "domain-specific" regions for faces (fusiform face area), places (parahippocampal place area), and words (visual word form area) [5].

The Distributed View: Associates mental functions with combinatorial brain activity across broad brain regions, drawing support from computer science models of massively parallel distributed processing and multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) [5].

Modern neuroscience has increasingly recognized that this historical dichotomy presents a false choice. Contemporary research demonstrates that category representations in the brain are both discretely localized and widely distributed [5]. The emerging consensus suggests that information is initially processed in localized regions then shared among other regions, leading to the distributed representations observed in multivariate analyses [5].

Population Coding and Distributed Representation

Multivariate predictive models emerged from theories grounded in neural population coding and distributed representation [1]. Neurophysiological studies have established that information about mind and behavior is encoded in the activity of intermixed populations of neurons, with population coding demonstrating that behavior can be more accurately predicted by joint activity across a population of cells than by individual neurons [1].

Table: Comparative Advantages of Population Coding

| Advantage | Mechanism | Functional Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness | Distributed information representation | System functionality persists despite individual neuron failure |

| Noise Filtering | Statistical averaging across populations | Improved signal-to-noise ratio in neural representations |

| High-Dimensional Encoding | Combinatorial patterns across neural ensembles | Capacity to represent complex, nonlinear representations |

| Flexibility | Dynamic reconfiguration of population patterns | Adaptive responses to changing task demands and contexts |

Distributed representation permits combinatorial coding, providing the capacity to represent extensive information with limited neural resources [1]. This generative capacity mirrors artificial neural networks that capitalize on these principles, where neurons encode features of input objects in a highly distributed, "many-to-many" fashion [1].

Methodological Approaches: Defining and Validating Brain Signatures

Multivariate Predictive Modeling

The core methodological innovation enabling modern brain signature research is multivariate predictive modeling, which explains behavioral outcomes as patterns of brain activity and/or structure across large numbers of brain features, often distributed across anatomical regions and systems [1]. Unlike traditional approaches that treat local brain response as the outcome to be explained, predictive models reverse this equation: sensory experiences, mental events, and behavior become the outcomes to be explained by combined brain measurements [1].

These models have been successfully developed for diverse mental states and processes, including:

- Perceptual processes: Object recognition, speech content, prosody [1]

- Cognitive functions: Memory, decision-making, semantic concepts, attention [1]

- Affective experiences: Emotion, pain, empathy [1]

- Clinical applications: Neurological and mental disorders [1]

Validation Frameworks for Brain Signatures

For brain signatures to achieve robust measurement status, they require rigorous validation across multiple cohorts and populations [2]. A statistically validated approach involves:

- Derivation Phase: Computing regional brain associations (e.g., gray matter thickness) for specific behavioral domains across multiple discovery cohorts [2]

- Consensus Mapping: Generating spatial overlap frequency maps from multiple discovery subsets and defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [2]

- Validation Testing: Evaluating replicability of cohort-based consensus model fits and explanatory power in separate validation datasets [2]

- Performance Comparison: Comparing signature model performance against theory-based models to establish superiority [2]

Table: Statistical Validation Framework for Brain Signatures

| Validation Phase | Key Procedures | Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Signature Derivation | Random sampling of discovery subsets; Regional association computation; Spatial frequency mapping | Consistency across samples; Effect size stability; Regional concordance |

| Consensus Definition | Threshold application for high-frequency regions; Mask creation; Spatial normalization | Regional overlap rates; Anatomical specificity; Network distribution |

| Cross-Validation | Independent cohort testing; Model fit assessment; Explanatory power analysis | Correlation of model fits; Effect size preservation; Generalizability indices |

| Competitive Testing | Comparison against alternative models; Predictive accuracy assessment; Clinical utility evaluation | Relative performance metrics; Effect size differences; Clinical correlation strength |

This validation approach has demonstrated that robust brain signatures can be achieved, yielding reliable and useful measures for modeling substrates of behavioral domains [2]. Studies applying this method to memory domains have found strongly shared brain substrates across different types of memory functions, suggesting both domain-specific and transdiagnostic signature elements [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Protocol for Signature Derivation and Validation

A representative experimental protocol for deriving and validating brain signatures involves these key methodological stages [2]:

Discovery Phase Protocol:

- Cohort Selection: Recruit representative sample(s) with standardized phenotypic assessments

- Neuroimaging Acquisition: Collect high-quality structural (e.g., T1-weighted) and/or functional MRI data using standardized sequences

- Data Preprocessing: Implement standardized preprocessing pipelines including:

- Motion correction and spatial normalization

- Surface-based reconstruction for cortical thickness measures

- Quality control exclusion criteria application

- Feature Extraction: Compute regional brain measures (e.g., gray matter thickness) in standardized atlas space

- Association Modeling: Calculate regional associations to behavioral outcomes in multiple randomly selected discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of size 400)

- Consensus Mask Creation: Generate spatial overlap frequency maps and define high-frequency regions as consensus signature masks

Validation Phase Protocol:

- Independent Cohort Testing: Apply consensus signatures to completely separate validation datasets

- Model Fit Assessment: Evaluate replicability of model fits across 50 random subsets of validation cohort

- Explanatory Power Comparison: Compare signature performance against competing theory-based models

- Generalizability Testing: Assess performance across demographic and clinical subgroups

Normative Modeling Framework for Transdiagnostic Applications

For transdiagnostic applications, a normative modeling framework can be implemented to predict individual-level deviations from normal brain-behavior relationships [4]:

- Normative Model Training: Use large discovery samples of healthy controls (n > 1,500) to train models predicting behavioral variables (e.g., BMI) from whole-brain gray matter volume [4]

- Individual Deviation Calculation: Compute difference between model-predicted and measured values (e.g., BMIgap = BMIpredicted - BMImeasured) [4]

- Clinical Application: Apply to clinical populations to identify systematic deviations in brain-behavior associations [4]

- Outcome Prediction: Test whether individual deviations predict future clinical or behavioral outcomes [4]

This approach has successfully identified distinct neurobiological subgroups in conditions such as ADHD that were previously undetectable by conventional diagnostic criteria [3]. Recent studies have identified delayed brain growth (DBG-ADHD) and prenatal brain growth (PBG-ADHD) subtypes with significant disparities in functional organization at the network level [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Brain Signature Research

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Brain Signature Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Signature Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Modalities | Structural MRI (T1-weighted); Functional MRI (resting-state, task-based); Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI); Electroencephalography (EEG); Magnetoencephalography (MEG) | Provides multimodal data sources for signature derivation; Enables cross-modal validation of signatures |

| Computational Frameworks | MVPA (Multivariate Pattern Analysis); Normative Modeling; Connectome-based Predictive Modeling; Deep Learning Architectures | Enables development of multivariate predictive models; Supports individual-level prediction |

| Software Platforms | AFNI; FSL; FreeSurfer; SPM; Connectome Workbench; Custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Provides standardized preprocessing and analysis pipelines; Enables reproducible signature derivation |

| Statistical Tools | Cross-validation; Bootstrapping; Permutation testing; Sparse Partial Least Squares (SPLS); Graph Theory Metrics | Supports robust statistical validation; Controls for multiple comparisons |

| Reference Datasets | Large-scale open datasets (UK Biobank, ABCD, HCP); Disease-specific consortia data; Local validation cohorts | Enables normative modeling; Provides independent validation samples |

| Behavioral Assessments | Standardized neuropsychological batteries; Clinical rating scales; Ecological momentary assessment; Cognitive task paradigms | Provides outcome measures for signature validation; Links neural patterns to behavioral phenotypes |

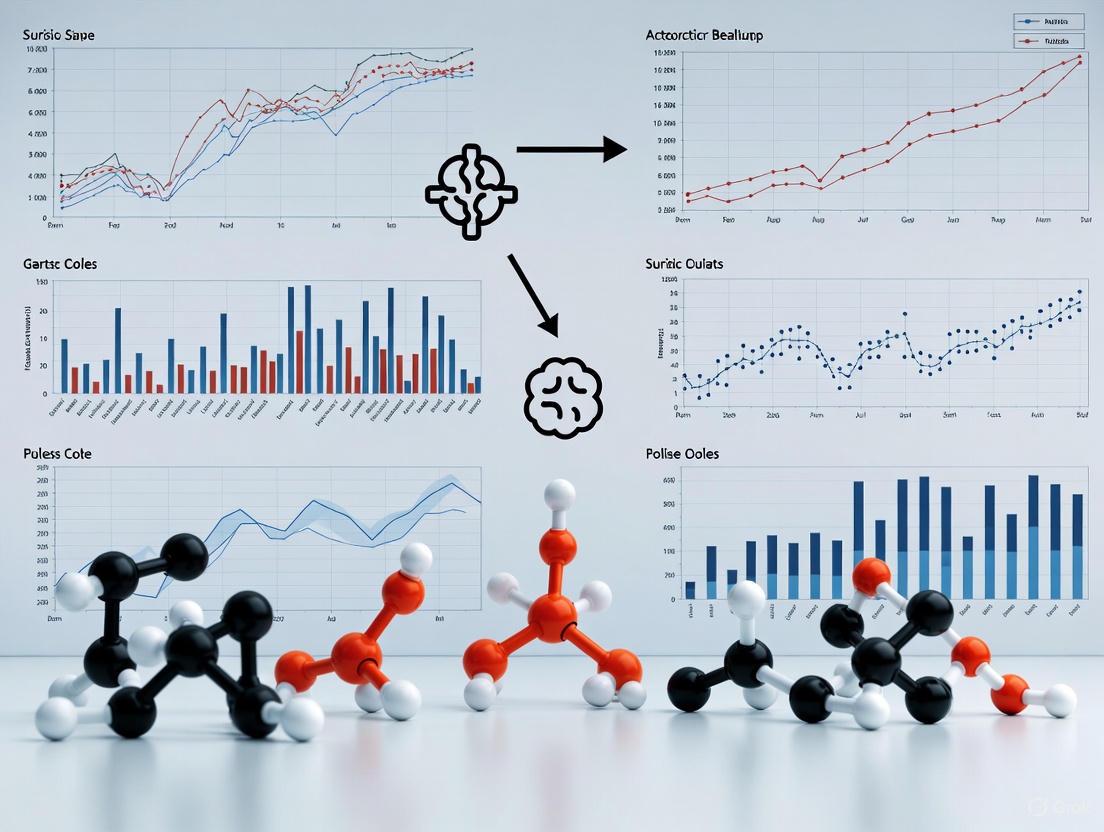

Visualization of Brain Signature Workflows

Conceptual Workflow for Signature Development

Brain Signature Development Workflow

Information Flow in Neural Representations

Information Flow in Neural Representations

Applications in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Transdiagnostic Biomarker Development

Brain signatures offer powerful transdiagnostic biomarkers for psychiatric drug development. The BMIgap tool exemplifies this approach, quantifying transdiagnostic brain signatures of current and future weight in psychiatric disorders [4]. This methodology:

- Identifies shared neurobiological mechanisms between metabolic and psychiatric disorders [4]

- Predicts future weight gain, particularly in younger individuals with recent-onset depression [4]

- Enables stratification of at-risk individuals for tailored interventions and metabolic risk control [4]

Applications across clinical populations have revealed:

- Schizophrenia: Show increased BMIgap (+1.05 kg/m²), suggesting brain-based metabolic vulnerability [4]

- Clinical High-Risk for Psychosis: Demonstrate intermediate BMIgap (+0.51 kg/m²) [4]

- Recent-Onset Depression: Exhibit decreased BMIgap (-0.82 kg/m²) [4]

Precision Neurodiversity Applications

The emerging framework of precision neurodiversity represents a shift from pathological models to personalized frameworks that view neurological differences as adaptive variations [3]. This approach leverages:

- Personalized Brain Network Architecture: Unique patterns of brain connectivity that remain stable over time, across tasks, and during aging processes [3]

- Neurobiological Subtyping: Identification of distinct subgroups within conventional diagnostic categories based on neurodevelopmental trajectories [3]

- Predictive Modeling: Using individual-specific "neural fingerprints" to predict cognitive, behavioral, and sensory outcomes [3]

Recent advances in deep generative modeling have enabled the inference of personalized human brain connectivity patterns from individual characteristics alone, with conditional variational autoencoders able to generate human connectomes with remarkable fidelity [3].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Methodological Considerations

Successful implementation of brain signatures in research and drug development requires addressing several methodological challenges:

- Statistical Power: Ensuring sufficient sample sizes for robust signature derivation and validation [2] [3]

- Reproducibility: Implementing rigorous cross-validation and independent replication protocols [2]

- Generalizability: Testing signatures across diverse populations and clinical settings [2] [4]

- Ethical Implementation: Addressing concerns about neurological privacy, community participation, and appropriate use [3]

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multimodal signatures that combine:

- Structural and functional neuroimaging data [1] [4]

- Genetic and molecular profiling information [3]

- Digital phenotyping from wearable sensors and behavioral monitoring [3]

- Clinical outcome measures and patient-reported outcomes [4]

This integration will enable more comprehensive brain-behavior mapping and enhance the predictive power of brain signatures for both basic research and clinical applications in drug development.

The progression from brain maps to multivariate models of mental states provides a strong foundation for empirical and theoretical development in cognitive neuroscience. As the science of multivariate brain models advances, the field continues to grapple with fundamental questions about how to define and evaluate mental constructs, and what it means to identify "brain representations" that underlie them [1]. Through iterative identification of potential mental constructs, development of neural measurement models, and empirical validation and refinement, brain signature research offers a path toward establishing more precise mappings between mind and brain with significant implications for research and therapeutic development.

The field of neuroscience has undergone a fundamental theoretical shift, moving from a framework of modular processing toward a more integrated understanding of population coding and distributed representation. This paradigm transformation represents a critical evolution in how we conceptualize neural computation—from viewing brain regions as specialized modules performing dedicated functions to understanding information as emerging from collective activity patterns across distributed neural populations. This shift is particularly relevant for brain signature validation in behavioral outcomes research, where identifying robust neural correlates of cognitive processes requires moving beyond localized markers to distributed activity patterns [2].

The modular view, which dominated early neuroscience, posited that specific brain regions were responsible for discrete cognitive functions. In contrast, population coding theory recognizes that information is represented not by individual neurons but by collective activity patterns across neural ensembles [6]. This distributed approach has profound implications for how we validate brain signatures as reliable predictors of behavioral outcomes, particularly in pharmaceutical development where connecting neural measures to cognitive performance is essential. The emergence of large-scale neural recordings and advanced multivariate analysis techniques has accelerated this theoretical shift, enabling researchers to quantify information distributed across thousands of simultaneously recorded neurons [7] [8].

Theoretical Foundations: From Modules to Populations

The Limitations of Modular Processing

The traditional modular perspective viewed the brain as a collection of specialized processors, each dedicated to specific cognitive functions. While this framework successfully identified broad functional-anatomical correlations, it faced significant limitations in explaining the robustness and flexibility of neural computation. Modular accounts struggled to explain how the brain achieves complex behaviors through coordinated activity across multiple regions, or how neural systems maintain function despite ongoing noise and neuronal loss [6].

Principles of Population Coding

Population coding theory addresses these limitations by proposing that information is represented collectively across groups of neurons. Several key principles define this approach:

- Collective Representation: Stimulus information is distributed across many neurons, with each neuron contributing partially to the overall representation [6]

- Heterogeneity and Diversity: Neural populations comprise neurons with diverse response properties, creating complementary information channels that enhance coding capacity [6]

- Noise Correlations: Correlated variability between neurons significantly impacts population information, either enhancing or limiting coding capacity depending on their structure [8]

- Dimensionality Expansion: Mixed selectivity at the population level increases the dimensionality of neural representations, enabling linear decoders to extract complex information [6]

Distributed Representation as a Computational Framework

Distributed representation extends population coding by emphasizing how information is encoded across multiple brain regions simultaneously. This framework recognizes that complex cognitive functions emerge from dynamic interactions between distributed networks rather than isolated processing in specialized modules. Research reveals that projection-specific subpopulations within cortical areas form specialized population codes with unique correlation structures that enhance information transmission to downstream targets [7].

Table 1: Core Concepts in Population Coding and Distributed Representation

| Concept | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Tuning | Neurons in a population have diverse stimulus preferences | Increases coding capacity and robustness to noise [6] |

| Noise Correlations | Trial-to-trial correlated variability between neurons | Shapes information content, especially in large populations [8] |

| Mixed Selectivity | Neurons respond to nonlinear combinations of task variables | Increases representational dimensionality for flexible decoding [6] |

| Projection-Specific Coding | Subpopulations targeting the same brain area show specialized correlations | Enhances information transmission to specific downstream targets [7] |

| Temporal Dynamics | Population patterns evolve over time during stimulus processing | Supports sequential processing strategies (e.g., coarse-to-fine) [9] |

Quantitative Evidence: Empirical Support for the Theoretical Shift

Information Scaling in Neural Populations

Experimental studies have quantitatively demonstrated the advantages of population coding over single-neuron representations. A key finding reveals that information scales with population size, but not uniformly across all neurons. Surprisingly, a small subset of highly informative neurons often carries the majority of stimulus information, while many neurons contribute minimally to population codes [6]. This sparse coding strategy balances metabolic efficiency with robust representation.

Research in parietal cortex demonstrates that projection-specific subpopulations show structured correlations that enhance population-level information about behavioral choices. These specialized correlation structures increase information beyond what would be expected from pairwise interactions alone, and this enhancement is specifically present during correct behavioral choices but absent during errors [7].

Temporal Dynamics in Population Codes

The temporal dimension of population coding reveals another advantage over static modular representations. In inferior temporal cortex, spatial frequency representation follows a coarse-to-fine processing strategy, with low spatial frequencies decoded faster than high spatial frequencies. The population's preferred spatial frequency dynamically shifts from low to high during stimulus processing, demonstrating how distributed representations evolve over time to support perceptual functions [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence Supporting Population Coding Over Modular Processing

| Experimental Finding | System Studied | Implication for Modular vs. Population Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Small informative subpopulations carry most information [6] | Auditory cortex | Challenges modular view that all neurons in a region contribute equally |

| Projection-specific correlation structures enhance information [7] | Parietal cortex | Shows specialized organization within populations, not just between regions |

| Coarse-to-fine temporal dynamics in spatial frequency coding [9] | Inferior temporal cortex | Demonstrates dynamic population processing not explained by static modules |

| Structured noise correlations impact population coding capacity [8] | Primary visual cortex | Reveals importance of population-level statistics beyond individual tuning |

| Network-level correlation motifs enhance choice information [7] | Parietal cortex output pathways | Shows how population structure enhances behaviorally relevant information |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols for Studying Population Codes

Large-Scale Neural Recording Techniques

Studying population codes requires methodological approaches capable of monitoring activity across many neurons simultaneously. Key techniques include:

- Calcium Imaging: Using two-photon microscopy to monitor activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons in behaving animals, often combined with retrograde labeling to identify projection-specific subpopulations [7]

- Electrophysiological Recordings: High-density electrode arrays that simultaneously record spiking activity from hundreds of neurons across multiple brain regions

- Neuroimaging Combination: Integrating single-neuron resolution data with mass signals (fMRI, EEG) to connect microscopic and macroscopic levels of analysis [6]

Statistical Modeling of Population Activity

Advanced statistical models are essential for quantifying information in neural populations:

- Vine Copula Models: Nonparametric methods that estimate multivariate dependencies among neural activity, task variables, and movement variables without assumptions about distribution forms. These models effectively isolate contributions of individual variables while accounting for correlations between them [7]

- Poisson Mixture Models: Capture spike-count variability and covariability in large populations, modeling both over- and under-dispersed response variability while supporting accurate Bayesian decoding [8]

- Dimensionality Reduction: Identify low-dimensional manifolds that capture the essential features of population activity related to specific task variables or behaviors [6]

Information-Theoretic Analysis

Information theory provides fundamental tools for quantifying population coding:

- Fisher Information: Measures how accurately small stimulus differences can be decoded from population activity

- Shannon Mutual Information: Quantifies how much population activity reduces uncertainty about stimuli or behavioral variables

- Decoding Analysis: Uses machine learning classifiers to quantify how well stimuli or behaviors can be predicted from population patterns

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for studying population codes, from data acquisition to theoretical insight:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Population Codes

| Tool/Resource | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Two-photon Calcium Imaging | Monitor activity of hundreds of neurons simultaneously | Recording population dynamics in behaving animals [7] |

| Retrograde Tracers | Identify neurons projecting to specific target areas | Labeling projection-specific subpopulations [7] |

| Vine Copula Models | Estimate multivariate dependencies without distributional assumptions | Isolating task variable contributions to neural activity [7] |

| Poisson Mixture Models | Capture spike-count variability and covariability | Modeling correlated neural populations for Bayesian decoding [8] |

| High-Density Electrode Arrays | Record spiking activity from hundreds of neurons | Large-scale monitoring of population activity across regions |

| Word2Vec Algorithms | Create distributed representations of discrete elements | Embedding high-dimensional medical data for confounder adjustment [10] |

Implications for Brain Signature Validation in Behavioral Outcomes Research

Redefining Neural Signatures

The shift to population coding necessitates a redefinition of what constitutes a valid brain signature. Rather than seeking localized activity in specific regions, robust brain signatures must capture distributed activity patterns that predict behavioral outcomes. Research demonstrates that consensus signature models derived from distributed neural patterns show higher replicability and explanatory power compared to theory-based models focusing on specific regions [2].

Statistical Validation of Population-Based Signatures

Validating population-based signatures requires specialized statistical approaches:

- Cross-Cohort Replication: Testing signature models across independent cohorts to establish robustness [2]

- Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps: Identifying consensus regions that consistently contribute to behavioral prediction across multiple samples [2]

- Explanatory Power Comparison: Comparing population-based signatures against theory-driven models to demonstrate superior predictive power [2]

Applications to Pharmaceutical Development

The population coding framework offers significant advantages for drug development:

- Sensitive Biomarkers: Distributed signatures may provide more sensitive biomarkers of treatment response by capturing subtle, distributed changes in neural processing

- Mechanistic Insights: Understanding how pharmacological interventions alter population dynamics rather than merely modulating activity in isolated regions

- Personalized Medicine: Population code variability between individuals may help explain differential treatment responses and guide personalized therapeutic approaches

The following diagram illustrates how projection-specific population codes create specialized information channels in cortical circuits:

The theoretical shift from modular processing to population coding and distributed representation represents a fundamental transformation in neuroscience with profound implications for brain signature validation in behavioral outcomes research. This paradigm change recognizes that complex cognitive functions emerge not from isolated specialized regions but from collective dynamics across distributed neural populations.

The evidence for this shift is compelling: projection-specific subpopulations show specialized correlation structures that enhance behavioral information [7], neural representations dynamically evolve during stimulus processing [9], and distributed population codes provide more robust predictors of behavioral outcomes than localized activity patterns [2]. Furthermore, advanced statistical methods now enable researchers to quantify information in these distributed representations and validate their relationship to cognitive function.

For pharmaceutical development and behavioral outcomes research, this theoretical shift necessitates new approaches to biomarker development and validation. Rather than seeking simple one-to-one mappings between brain regions and cognitive functions, researchers must develop multivariate signatures that capture distributed activity patterns predictive of treatment response and behavioral outcomes. The future of brain signature validation lies in embracing the distributed, population-based nature of neural computation, leveraging advanced statistical models to extract meaningful signals from complex neural population data, and establishing robust links between these distributed signatures and clinically relevant behavioral outcomes.

In the pursuit of robust brain signatures for behavioral outcomes, understanding the core statistical computations the brain performs on sequential information is paramount. Research increasingly indicates that the brain acts as a near-optimal inference device, constantly extracting statistical regularities from its environment to generate predictions about future events [11]. This process relies on fundamental building blocks of sequence knowledge, primarily Item Frequency (IF), Alternation Frequency (AF), and Transition Probabilities (TP). These computations provide a foundational model for understanding how the brain builds expectations, which in turn can be validated as reliable signatures of perception, decision-making, and other behavioral substrates [2] [12]. Framing these inferences within a statistical learning framework allows researchers to move beyond mere correlation and toward a mechanistic understanding of the brain-behavior relationship, with significant implications for developing endpoints in clinical trials and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of the Key Statistics

Sequences of events can be characterized by a hierarchy of statistics, each capturing a different level of abstraction [11] [12]. The brain is sensitive to these statistics, which are computed over different timescales and form the basis for statistical learning.

Item Frequency (IF)

- Definition: Item Frequency is the simplest statistic, representing the probability of each item occurring in a sequence, independent of order or context [12]. For a binary sequence with items A and B, it is defined as p(A) = 1 - p(B).

- Computational Role: IF involves a simple count of each observation type. It is ignorant of the order of items and the number of repetitions and alternations [13].

- Brain Signature Correlate: Sensitivity to global IF manifests in brain signals related to habituation. Early post-stimulus brain waves, for instance, denote a sensitivity to item frequency estimated over a long timescale [12].

Alternation Frequency (AF)

- Definition: Alternation Frequency measures whether successive observations are identical (a repetition) or different (an alternation). It is defined as p(alternation) = 1 - p(repetition) [13] [12].

- Computational Role: AF considers pairs of items but is ignorant of the specific identity of the items; it treats repetitions A→A and B→B identically, and alternations A→B and B→A identically [13] [11].

- Brain Signature Correlate: AF is embedded within the more complex space of transition probabilities. Its contribution to brain signatures can be isolated in mid-latency brain responses when compared to models that specifically account for it [12].

Transition Probabilities (TP)

- Definition: Transition Probabilities represent the probability of observing a specific item given the context of the immediately preceding item. For a binary sequence, this involves two conditional probabilities: p(B|A) and p(A|B) [11] [12].

- Computational Role: TP is the simplest statistical information that genuinely reflects a sequential regularity, as it captures information about item frequency, their co-occurrence (AF), and their serial order [12]. Estimating TP requires tracking two statistics simultaneously and applying one of them depending on the context [13].

- Brain Signature Correlate: The learning of recent TPs is reflected in mid-latency and late brain waves. Magnetoecephalography (MEG) studies show that these brain signals conform qualitatively and quantitatively to the computational properties of local TP inference [12]. The local TP model, which infers a non-stationary transition probability matrix, is proposed as a core building block of human sequence knowledge, unifying findings on surprise signals, sequential effects, and the perception of randomness [11].

The relationships between these statistics are hierarchical, as illustrated in the following diagram.

The following tables summarize key quantitative data from cross-modal experiments investigating these statistical inferences. The findings demonstrate that in conditions of perceptual uncertainty, the brain's decision-making is better explained by learning models based on past responses than by the actual stimuli.

Table 1: Model Performance in Predicting Participant Choices (Log-Likelihood Analysis)

| Sensory Modality | Trial Difficulty | Stimulus-Only Model | Response-Based Learning Model | Stimulus-Based Learning Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory | Easy | Superior Performance | Inferior Performance | Comparable or Better |

| Auditory | Difficult | Inferior Performance | Superior Performance | Significantly Outperformed |

| Vestibular | Easy | Superior Performance | Inferior Performance | Comparable or Better |

| Vestibular | Difficult | Inferior Performance | Superior Performance | Outperformed (TP model not significant) |

| Visual | Easy | Superior Performance | Inferior Performance | Comparable or Better |

| Visual | Difficult | Inferior Performance | Superior Performance | Significantly Outperformed |

Note: Based on log-likelihood analysis from [13]. "Superior Performance" indicates the model that best predicted participants' responses. Learning models (IF, AF, TP) outperformed stimulus-only models in difficult trials, and response-based variants of these learning models generally outperformed stimulus-based variants.

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Statistical Inference Characteristics

| Statistic | Computational Description | Timescale of Integration | Key Brain Response Correlate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item Frequency (IF) | Count of each item: p(A) vs p(B) | Long-timescale (Global) / Habituation | Early post-stimulus evoked potential [12] |

| Alternation Frequency (AF) | Frequency of repetitions vs. alternations | Local (Leaky Integration) | Modulates mid-latency responses [12] |

| Transition Probabilities (TP) | Conditional probabilities: p(B|A), p(A|B) | Local (Non-stationary, Recent History) | Mid-latency and late surprise signals [11] [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To guide replication and validation studies, the following section outlines the core methodologies from key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol 1: Cross-Modal Psychophysical Task with Learning Models

This protocol is adapted from the study that directly compared IF, AF, and TP models across auditory, vestibular, and visual modalities [13].

- Objective: To determine whether recent decisions or recent stimuli cause serial dependence in perceptual decision-making.

- Task Design: A one-interval, two-alternative forced-choice (2AFC) paradigm. Participants are presented with a perceptual stimulus on each trial and must make a binary decision (e.g., identify a syllable as "/ka/" or "/to/", or the direction of dot motion).

- Stimuli:

- Auditory: Syllables such as /ka/ and /to/.

- Vestibular: Direction of passive self-motion (left/right, forward/backward).

- Visual: Direction of coherent dot motion (up/down).

- Stimulus Difficulty: Stimulus intensities are titrated to threshold level to ensure a sufficient proportion of difficult trials where sensory evidence is ambiguous.

- Data Analysis:

- Model Fitting: Three learning models (IF, AF, TP) are fitted to the trial-by-trial sequence of either participant responses or generative stimuli. A "leak factor" (ω) is tested to find the optimal timescale of integration for each participant and model.

- Prediction: The models compute a predictive likelihood for the next response on each trial.

- Model Comparison: The log-likelihood of participants' actual choices given each model's predictions is computed. Models are compared separately for "easy" and "difficult" trials, categorized based on participant accuracy.

- Key Outcome Measures: Difference in log-likelihood (ΔLL) between response-based and stimulus-based models; significance of ΔLL in difficult trials.

Protocol 2: MEG Investigation of Multiscale Sequence Learning

This protocol is designed to identify the distinct brain signatures of different statistical inferences [12].

- Objective: To investigate whether successive brain responses reflect the progressive extraction of sequence statistics at different timescales.

- Stimuli: Binary auditory sequences (sounds A and B) generated with different underlying statistical biases:

- Frequency-biased (one item more frequent).

- Alternation-biased (alternations more frequent than repetitions).

- Repetition-biased (repetitions more frequent than alternations).

- Fully stochastic (all transitions equally likely).

- Procedure: Participants passively listen to sequences or perform a simple task while magnetoencephalography (MEG) data is recorded.

- Computational Modeling:

- Model Families: Three families of learning models (IF, AF, TP) are defined.

- Timescale of Integration: For each statistics, both "global" (all observations weighted equally) and "local" (leaky integration, discounting past observations) models are implemented using Bayesian inference.

- Surprise Quantification: On each trial, model-based surprise is quantified as the negative logarithm of the estimated probability of the actual observation:

Surprise = -log P(observation).

- Neural Data Analysis: The theoretical surprise levels from each model are regressed against the time-resolved MEG signal to identify which model best explains the variance in brain activity at different latencies post-stimulus.

- Key Outcome Measures: Model fit between theoretical surprise and evoked brain responses; identification of which brain wave component (early, mid-latency, late) is best explained by which statistical model (IF, AF, TP).

The logical workflow for designing and analyzing such an experiment is as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and computational tools for research in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Item / Methodology | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Alternative Forced Choice (2AFC) | A psychophysical task where participants choose between two options per trial. | Core behavioral paradigm for measuring perceptual decisions and sequential effects [13] [11]. |

| Leaky Integrator Model | A model component where past observations are exponentially discounted, implementing local (not global) integration. | Captures the brain's preference for recent history when estimating statistics like IF, AF, and TP [13] [12]. |

| Model Log-Likelihood Comparison | A statistical method for comparing how well different computational models predict observed data. | Used to arbitrate between models that use stimuli vs. responses as input, and between IF, AF, and TP models [13]. |

| Magnetoencephalography (MEG) | A neuroimaging technique that records magnetic fields generated by neural activity with high temporal resolution. | Links the computational output of learning models (e.g., surprise) to specific, time-locked brain signatures [12]. |

| Transition Probability Matrix | A representation of the probabilities of moving from one state (e.g., stimulus) to another. | The core data structure inferred by the proposed minimal model of human sequence learning [11]. |

| Bayesian Inference Framework | A method for updating the probability of a hypothesis (e.g., a statistic) as more evidence becomes available. | The underlying computational principle for the learning models that estimate IF, AF, and TP in a trial-by-trial manner [11] [12]. |

Theoretical Debate: Transition Probabilities vs. Chunking

While the TP model offers a unifying account, an alternative theoretical framework—the chunking approach—makes distinct predictions. Models like PARSER and TRACX propose that statistical learning occurs by segmenting sequences into cohesive "chunks" through trial and error [14].

- Key Difference: The fundamental difference lies in the mental representation of sub-units. The TP approach suggests that the mental representations for both a full unit (e.g., ABC) and its sub-units (AB, BC) are reinforced with exposure. In contrast, chunking models predict that once a full unit is discovered, the sub-units are no longer parsed separately and their representations decay due to competition or binding processes [14].

- Experimental Evidence: Studies using offline two-alternative forced-choice tasks with auditory syllables or spatially-organized visual shapes have found support for the chunking approach. After extended exposure, recognition of full units is stronger than for sub-units, a pattern predicted by chunking models but not by the pure transitional probability approach [14].

This ongoing debate highlights that the core building blocks of sequence learning may involve more than one mechanism, and their relative contributions must be considered when defining brain signatures for behavior.

The Critical Importance of Timescales in Statistical Learning and Neural Inference

The human brain is fundamentally a prediction engine, continuously extracting regularities from the environment to guide behavior. Central to this function is statistical learning—the ability to detect and internalize patterns across time and space. The temporal scales at which these statistics unfold are not monolithic; real-world learning involves parallel processes operating over seconds, minutes, and days. Understanding these multi-timescale dynamics is critical for developing accurate brain signatures that can reliably predict behavioral outcomes in health and disease. Research framed within the broader context of validating brain-behavior relationships shows that ignoring this temporal complexity leads to incomplete or misleading models of brain function [2]. This review synthesizes current evidence on how the brain learns and represents statistical information across multiple timescales, detailing the experimental paradigms and neural inference mechanisms that underpin this core cognitive faculty. We argue that a multi-timescale perspective is indispensable for building robust, transdiagnostic brain signatures for behavioral validation, with significant implications for basic cognitive science and applied drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Single-Scale to Multi-Timescale Learning

Defining the Timescale Problem in Learning

Traditional models of learning often treated the process as unitary, focusing on a single type of dependency or a fixed temporal window. However, the environment contains temporal dependencies unfolding simultaneously at multiple timescales [15]. For instance, in language, we process rapid phonotactic probabilities while simultaneously tracking slower discourse-level patterns. In motor learning, we execute immediate sequences while adapting to longer-term shifts in task dynamics. Statistical learning is broadly defined as the ability to extract these statistical properties of sensory input [16]. When this learning occurs without conscious awareness of the acquired knowledge, it is often termed implicit statistical learning [16]. A key challenge for cognitive neuroscience is to explain how the brain concurrently acquires, represents, and utilizes statistical information that varies in its temporal grain.

The Interplay of Memory Systems Across Timescales

Learning across timescales is supported by dynamic interactions between the brain's declarative and nondeclarative memory systems. The declarative memory system, dependent on the medial temporal lobe (MTL) including the hippocampus, supports the rapid encoding of facts and events [16]. In contrast, nondeclarative memory encompasses various forms of learning, including skills and habits, and involves processing areas like the basal ganglia (striatum), cerebellum, and neocortex [16]. These systems do not operate in isolation; they frequently interact or compete during learning tasks [16]. The engagement of each system appears to be partly determined by the temporal structure of the learning problem. For instance, learning that requires the flexible integration of relationships across longer gaps may preferentially engage hippocampal networks, whereas the incremental acquisition of sensorimotor probabilities may rely more on corticostriatal circuits.

Experimental Evidence of Multi-Timescale Learning

Behavioral Paradigms and Key Findings

Researchers have developed sophisticated paradigms to isolate learning at different temporal scales within the same task. A seminal approach involves a visuo-spatial motor learning game ("whack-a-mole") where participants learn to predict target locations based on regularities operating at distinct timescales [15].

Table 1: Key Experimental Paradigms for Studying Multi-Timescale Learning

| Paradigm | Short-Timescale Manipulation | Long-Timescale Manipulation | Key Behavioral Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visuo-Spatial "Whack-a-Mole" [15] | Order of pairs of sequential locations | Set of locations in first vs. second half of game | Context-dependent sensitivity to both timescales; stronger learning for short timescales |

| Statistical Pain Learning [17] | Transition probability between successive pain stimuli | Underlying frequency of high/low pain stimuli over longer blocks | Participants learned stimulus frequencies; transition probability learning was more challenging |

| Sensory Decision-Making (Mice) [18] | Trial-by-trial updates based on immediate stimulus, action, and reward | History-dependent updates over multiple trials | Revealed asymmetric updates after correct/error trials and non-Markovian history dependence |

In the "whack-a-mole" paradigm, participants showed context-dependent sensitivity to order information at both short and long timescales, with evidence of stronger learning for short-timescale regularities [15]. This suggests that while the brain can extract parallel regularities, processing advantages may exist for more immediate dependencies. Similarly, in a statistical pain learning study, participants were able to track and explicitly predict the fluctuating frequency of high-intensity painful stimuli over volatile sequences, a form of longer-timescale inference [17]. However, learning the shorter-timescale transition probabilities (e.g., P(High|High)) proved more challenging for a substantial subset of participants [17]. These findings highlight that learning efficacy is not uniform across timescales and can be influenced by the complexity and salience of the statistics.

Quantitative Models of Learning Dynamics

Computational modeling has been essential for characterizing the algorithms the brain uses to learn across timescales. Several classes of models have been employed, each with distinct implications for temporal processing.

Table 2: Computational Models for Multi-Timescale Statistical Learning

| Model Class | Core Principle | Timescale Handling | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Inference (Jump Models) [17] | Optimal inference that weights new evidence against prior beliefs, with a prior for sudden change points. | Infers volatility of the environment, dynamically adjusting the effective learning timescale. | Best fit for human behavior in volatile pain sequences; tracks underlying stimulus frequencies [17]. |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [18] | Flexible, nonparametric learning rules inferred from data using recurrent units (e.g., GRUs). | Can capture non-Markovian dynamics, allowing updates to depend on multi-trial history. | Improved prediction of mouse decision-making; revealed history dependencies lasting multiple trials [18]. |

| Gated Recurrent Networks [15] | Trained to predict upcoming events, similar to the goal of human participants in learning tasks. | Develops internal representations that mirror human sensitivity to nested temporal structures. | Showed learning timecourses and similarity judgments that paralleled human participant data [15]. |

A critical finding from model comparison studies is that human learning in volatile environments is often best described by Bayesian "jump" models that explicitly represent the possibility of sudden changes in underlying statistics [17]. This suggests the brain employs mechanisms for multi-timescale inference, dynamically adjusting the influence of past experiences based on inferred environmental stability. Furthermore, flexible nonparametric approaches using RNNs have demonstrated that real animal learning strategies often deviate from simple, memoryless (Markovian) rules, instead exhibiting rich dependencies on trial history [18].

Diagram 1: Neural inference system for multi-timescale learning, showing how short and long-timescale systems interact, supported by declarative and non-declarative memory systems.

Neural Inference and the Brain Signatures of Learning

Neural Correlates of Multi-Timescale Processing

Neuroimaging studies have begun to dissect the neural architecture supporting learning across timescales. In a statistical pain learning fMRI study, different computational quantities were mapped onto distinct brain regions: the inferred frequency of pain correlated with activity in sensorimotor cortical regions and the dorsal striatum, while the uncertainty of these inferences was encoded in the right superior parietal cortex [17]. Unexpected changes in stimulus statistics—driving the update of internal models—engaged a network including premotor, prefrontal, and posterior parietal regions [17]. This distribution of labor suggests that longer-timescale inferences (like frequency) are computed in domain-general association areas and then fed back to influence processing in primary sensory regions, effectively shaping perception based on temporal context.

Towards Validated Brain Signatures for Behavioral Outcomes

The ultimate goal of understanding learning mechanisms is to derive robust brain signatures that can predict behavioral outcomes and clinical trajectories. A promising approach involves normative modeling, which maps individual deviations from a population-standard brain-behavior relationship. For instance, the BMIgap tool quantifies the difference between a person's predicted body mass index (based on brain structure) and their actual BMI [4]. This brain-derived signature was transdiagnostic, showing systematic deviations in schizophrenia, clinical high-risk states for psychosis, and recent-onset depression, and it predicted future weight gain [4]. This demonstrates how quantifying individual deviations from normative, multi-timescale learning patterns could yield powerful biomarkers for metabolic risk in psychiatric populations. The validation of such signatures requires testing their replicability across diverse cohorts and demonstrating superior explanatory power compared to theory-based models [2].

Methodological Considerations and Experimental Protocols

Advanced Experimental Designs

Capturing learning across timescales requires moving beyond traditional cross-sectional designs to methods that embrace temporal dynamics. Time-series analyses, which involve repeated measurements at equally spaced intervals with preserved temporal ordering, are essential for observing how behaviors unfold [19]. Techniques like autocorrelation (measuring dependency within a series), recurrence quantification analysis (quantifying deterministic patterns), and spectral analysis (decomposing series into constituent cycles) are powerful tools for this purpose [19].

For complex interventions, the Hybrid Experimental Design (HED) is a novel approach that involves sequential randomizations of participants to intervention components at different timescales (e.g., monthly randomization to coaching sessions combined with daily randomization to motivational messages) [20]. This design allows researchers to answer scientific questions about constructing multi-component interventions that operate on different temporal rhythms, mirroring the multi-timescale nature of real-world learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Multi-Timescale Learning Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Task Software | Custom "Whack-a-Mole" Paradigm [15], Sensory Decision-Making Task [18] | Presents controlled sequences of stimuli with embedded statistical regularities at pre-defined timescales to elicit and measure learning. |

| Computational Modeling Tools | Bayesian Inference Models (e.g., "Jump" Models) [17], RNNs/DNNs for rule inference [18] | Provides a quantitative framework to characterize the algorithms underlying learning behavior and their associated timescales. |

| Neuroimaging Acquisition & Analysis | fMRI, Structural MRI (for GMV) [4] [17], EEG | Measures neural activity and structure in vivo to correlate with computational variables (e.g., inference, uncertainty) and build brain signatures. |

| Normative Modeling Frameworks | BMIgap Calculation Pipeline [4] | Enables the quantification of individual deviations from population-standard brain-behavior relationships, creating transdiagnostic biomarkers. |

A Protocol for a Multi-Timescale Learning Experiment

A detailed protocol for a human visuo-spatial statistical learning experiment, based on [15], is as follows:

- Participant Recruitment & Exclusion Criteria: Recruit a pre-determined sample size (e.g., N=96) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Pre-register exclusion criteria such as poor accuracy on attention checks (<70%) or excessive missed responses during gameplay (>25%).

- Stimulus & Task Design:

- Create 8 distinct mini-games, each with a unique background and target image.

- For each game, design a sequence of target appearances in one of 9 locations. Embed two types of regularities:

- Short Timescale: Define pairs of sequential locations that predictably follow one another.

- Long Timescale: Define a set of locations that appear more frequently in the first half of the game versus the second half.

- Counterbalance the assignment of order rules to specific background/target pairs across participants.

- Procedure:

- Exposure/Practice: Give participants a practice game with random target locations.

- Training: Have participants play each of the 8 mini-games once per round for 8 rounds. On each trial, the target appears and the participant must click it within 800 ms to receive points.

- Probe Trials: Periodically, interrupt gameplay to have participants predict the upcoming target location.

- Post-Test: After all rounds, administer a similarity judgement task where participants compare games based on their temporal order properties.

- Data Analysis:

- Behavioral: Analyze prediction accuracy during probe trials and similarity judgments using ANOVA and clustering techniques to assess sensitivity to short vs. long-timescale structures.

- Computational Modeling: Train a gated recurrent network to predict the next location in the sequences. Compare the model's internal representations and sensitivity profiles to the human data.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for a multi-timescale statistical learning study, covering design, procedure, and analysis phases.

The critical importance of timescales in statistical learning and neural inference is now undeniable. The brain does not rely on a single, monolithic learning system but rather employs a suite of interacting mechanisms, supported by distinct but communicating neural networks, to extract regularities that unfold over seconds, minutes, and days. The evidence shows that learning efficacy, the underlying neural substrates, and the optimal computational models all vary significantly depending on the temporal grain of the statistical structure. Ignoring this multi-timescale nature results in an impoverished understanding of learning. The future of this field lies in further elucidating how the declarative and nondeclarative memory systems interact and compete during learning, developing even more flexible nonparametric models to infer complex, history-dependent learning rules, and leveraging normative modeling to build robust, transdiagnostic brain signatures. These signatures, validated against behavioral outcomes across healthy and clinical populations, hold immense promise for revolutionizing how we diagnose, stratify, and treat neuropsychiatric disorders, ultimately delivering more personalized and effective interventions in both clinical practice and drug development.

Methodologies for Signature Derivation: From Neuroimaging to Hybrid In Silico Models

The "brain signature" concept represents a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions associated with specific cognitive functions or behavioral outcomes. This methodology has emerged as a powerful alternative to hypothesis-driven techniques, with the potential to maximally characterize brain substrates of behavioral domains by selecting neuroanatomical features based solely on performance metrics of prediction or classification [2]. Unlike theory-driven models that rely on pre-specified regions of interest, signature approaches derive their explanatory power from agnostic searches across high-dimensional brain data, free of prior suppositions about which brain areas matter most [21].

The validation of brain signatures as robust measures of behavioral substrates requires rigorous testing across multiple, independent cohorts to ensure generalizability beyond single datasets [2]. This technical guide examines the integrated methodology of voxel-based regressions and consensus signature masks—a approach that has demonstrated superior performance in explaining behavioral outcomes compared to standard theory-based models [2] [21]. When properly validated, these signatures provide reliable and useful measures for modeling substrates of behavioral domains, offering significant potential for both basic neuroscience research and clinical applications in drug development [22].

Theoretical Foundations and Core Principles

Voxel-Based Morphometry and Regression Fundamentals

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) provides the foundational methodology for quantifying regional brain structure in a comprehensive, whole-brain manner. The technical process begins with MRI scans that are aligned and normalized to a standardized template space, typically using the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space as a reference [23]. The gray matter density maps are then segmented, extracted, and smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel (commonly 8-mm FWHM) to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio while preserving anatomical specificity [23]. The resulting data matrix represents brain structure at the voxel level—typically comprising hundreds of thousands of data points per subject—which serves as the input for high-dimensional regression modeling.

The core innovation in modern signature development lies in applying regression analysis at each voxel to identify associations with behavioral outcomes while correcting for multiple comparisons [21]. This voxel-wise approach generates statistical parametric maps that quantify the relationship between brain structure and cognition across the entire brain volume, without being constrained by anatomical atlas boundaries. The method captures both known and novel neural substrates of behavior, potentially revealing "non-standard" regions that do not conform to prespecified atlas parcellations but may more accurately reflect the underlying brain architecture supporting cognitive functions [21].

Consensus Signature Mask Conceptual Framework

The consensus signature mask methodology addresses a critical challenge in data-driven neuroscience: the instability of feature selection across different samples or cohorts. This approach transforms voxel-wise association maps into robust, binary masks through a resampling and frequency-based aggregation process [2]. The technical process involves computing regional brain associations to behavioral outcomes across multiple randomly selected discovery subsets, then generating spatial overlap frequency maps that quantify the reproducibility of each voxel's association with the outcome measure.

The consensus thresholding operation identifies high-frequency regions that consistently demonstrate associations with the behavioral substrate across resampling iterations. These regions are defined as the consensus signature mask—a spatially stable representation of the brain-behavior relationship that has demonstrated higher replicability and explanatory power compared to signatures derived from single cohorts [2]. This method effectively separates robust, generalizable neural substrates from sample-specific noise or idiosyncrasies, producing signatures that perform reliably when applied to independent validation datasets.

Methodological Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Standards

The initial phase requires careful attention to imaging protocols and quality control. Structural MRI data should be acquired using standardized sequences, with specific parameters varying by scanner manufacturer and magnetic field strength. For multi-cohort studies, harmonization protocols are essential to minimize site-specific effects. The preprocessing pipeline typically includes the following key stages, often implemented using established software platforms like Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) or FSL:

- Spatial normalization to a standardized template (e.g., MNI space)

- Tissue segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid

- Spatial smoothing with a Gaussian kernel (typically 8-10mm FWHM)

- Quality control procedures to identify artifacts or registration failures

For the UC Davis Aging and Diversity cohort referenced in validation studies, specific parameters included MRI acquisition on a 1.5T scanner, with subsequent processing using VBM protocols to generate gray matter density maps [21]. In the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohorts, both 1.5T and 3T scanners were used across different phases, with careful cross-protocol harmonization [21].

Signature Derivation Protocol

The core signature derivation process follows a structured computational workflow:

Figure 1. Workflow for consensus signature mask derivation through resampled voxel-wise regression analysis.

The specific analytical steps include:

Random Subsampling: Create multiple discovery subsets (e.g., 40 random samples of n=400 participants) from the full discovery cohort to assess feature stability [2].

Voxel-wise Regression Analysis: For each subset, perform regression at each voxel to identify associations with the behavioral outcome, typically using gray matter thickness or density as the structural metric [2].

Multiple Comparison Correction: Apply appropriate statistical correction (e.g., family-wise error or false discovery rate) to control for the massive multiple testing inherent in voxel-wise analyses [21].

Spatial Frequency Mapping: Compute the frequency with which each voxel shows a significant association across the resampled subsets, creating a reproducibility map.

Consensus Mask Generation: Apply a frequency threshold to define consensus regions, typically selecting voxels that show significant associations in a high proportion (e.g., >70%) of resamples [2].

Validation Framework

Robust validation requires application of the derived consensus signature to independent cohorts that were not involved in the discovery process. The validation protocol should assess:

- Replicability: Correlation of signature model fits across multiple random subsets of the validation cohort [2]

- Explanatory Power: Comparison of variance explained (R²) between signature models and competing theory-based models [21]

- Generalizability: Performance consistency across cohorts with different demographic, clinical, or scanner characteristics [2]

In published implementations, this validation framework has demonstrated that consensus signature models produce highly correlated fits in validation cohorts (e.g., correlation of model fits in 50 random subsets) and outperform theory-driven models in explaining behavioral outcomes [2].

Quantitative Performance and Validation Data

Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

Table 1. Comparative performance of different analytical approaches in explaining behavioral outcomes.

| Methodological Approach | Cohort | Behavioral Domain | Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Signature Mask [2] | Multi-cohort validation | Everyday cognition memory | Model replicability | High correlation in validation subsets |

| Voxel-based Signature [21] | ADNI 1 (n=379) | Episodic memory | Explanatory power vs. theory-driven models | Outperformed standard models |

| Random Survey SVM [23] | ADNI (n=649) | AD vs. HC classification | Prediction accuracy | >90% accuracy for AD-HC classification |

| Stacked Custom CNN [24] | Tumor classification | Brain tumor detection | Classification accuracy | 98% accuracy |

| Explainable AI [25] | Migraine (n=64) | Migraine classification | Accuracy/AUC | >98.44% accuracy, AUC=0.99 |

Technical Parameters and Implementation Details

Table 2. Technical specifications for consensus signature derivation protocols.

| Parameter | Implementation Examples | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery subset size | n=400 [2] | Balances stability and computational feasibility |

| Number of resamples | 40 iterations [2] | Provides stable frequency estimates |

| Spatial smoothing kernel | 8mm FWHM [23] | Reduces noise while preserving anatomical specificity |

| Consensus threshold | High-frequency regions [2] | Selects most reproducible associations |

| Validation samples | 50 random subsets [2] | Assesses replicability in independent data |

| Multiple comparison correction | Family-wise error correction [21] | Controls false positive rates |

Advanced Computational Approaches

Machine Learning Integration

Modern implementations increasingly integrate machine learning classifiers with VBM features to enhance predictive accuracy. The Random Survey Support Vector Machine (RS-SVM) approach represents one advanced framework that combines feature detection with robust classification [23]. This method processes VBM data by first extracting differences between case and control groups, then applies a similarity metric to identify discriminative features:

Where vm' and vn' represent voxel values for different groups, and ρ_i quantifies feature similarity [23]. This approach has demonstrated particularly strong performance in Alzheimer's disease classification, achieving prediction accuracy exceeding 90% for AD versus healthy controls [23].

Deep Learning Architectures

More recently, custom convolutional neural networks have been combined with VBM preprocessing to further advance classification performance. One implementation using a stacked custom CNN with 15 layers, incorporating specialized activation functions and adaptive median filtering with Canny edge detection, achieved 98% accuracy in brain tumor classification [24]. These approaches demonstrate how traditional VBM methodology can be integrated with modern deep learning architectures while maintaining the spatial specificity of voxel-based methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3. Essential resources for implementing voxel-based regressions and consensus signature analysis.

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data | ADNI database [23] [21] | Provides standardized multi-cohort datasets | UC Davis Aging and Diversity Cohort [21] |

| Processing Software | SPM, FSL, FreeSurfer [21] | Spatial normalization, tissue segmentation | VBM processing using SPM [23] |

| Statistical Platforms | R, Python, MATLAB [25] | Voxel-wise regression, multiple comparison correction | Linear regression models [2] |

| Atlas Resources | AAL atlas, MNI template [23] | Spatial reference for coordinate systems | ROI definition using AAL [23] |

| Machine Learning | SVM, CNN, Random Forest [23] [24] | Feature selection, classification | Random Survey SVM [23] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Integration

Integrated Analytical Pipeline

The complete analytical pathway for consensus signature development incorporates multiple interdependent stages, with validation checkpoints at critical junctures:

Figure 2. Complete analytical pipeline from data acquisition to clinical application with integrated validation.

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Trials

The translation of brain signature methodologies to drug development pipelines offers significant potential for improving trial efficiency and success rates. The emerging framework of biology-first Bayesian causal AI represents a promising approach for integrating neuroimaging biomarkers into clinical development [22]. This methodology starts with mechanistic priors grounded in biology—potentially including brain signature data—and integrates real-time trial data as it accrues, enabling adaptive trial designs that can refine inclusion criteria, inform optimal dosing strategies, and guide biomarker selection [22].

In practical applications, this approach has demonstrated value in identifying patient subgroups with distinct characteristics that predict therapeutic response. In one multi-arm Phase Ib oncology trial, Bayesian causal AI models trained on biospecimen data identified a subgroup with a distinct metabolic phenotype that showed significantly stronger therapeutic responses [22]. Similar approaches could be applied to neuroscience drug development using consensus brain signatures as stratification biomarkers.

Regulatory agencies are increasingly supportive of these innovative methodologies. The FDA has announced plans to issue guidance on the use of Bayesian methods in the design and analysis of clinical trials by September 2025, building on earlier initiatives such as the Complex Innovative Trial Design Pilot Program [22]. This regulatory evolution creates opportunities for incorporating validated brain signatures into clinical trial frameworks for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

The integration of voxel-based regressions with consensus signature masks represents a methodological advance in data-driven neuroscience. This approach provides a robust framework for identifying brain-behavior relationships that generalize across cohorts and outperform theory-driven models in explanatory power [2] [21]. The technical protocols outlined in this guide—from standardized VBM preprocessing to resampled consensus generation and rigorous multi-cohort validation—provide a roadmap for implementing these methods in both basic research and applied drug development contexts.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on multi-modal integration, combining structural signatures with functional, metabolic, and genetic data to create more comprehensive models of brain-behavior relationships [4]. Additionally, the integration of explainable AI techniques will be essential for enhancing the interpretability and clinical translation of these data-driven approaches [25]. As these methodologies mature, consensus brain signatures may become valuable tools for patient stratification, treatment targeting, and clinical trial enrichment in both academic research and industry drug development pipelines.

The pursuit of objective biological signatures, or biomarkers, is revolutionizing behavioral outcomes research and drug development. For complex conditions influenced by brain structure and function—from psychiatric disorders to neurodegenerative diseases—machine learning (ML) offers powerful tools to decipher subtle patterns from high-dimensional data. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three pivotal ML methodologies: Support Vector Machines (SVM), Deep Learning, and Interpretable Feature Selection. Framed within the context of identifying robust brain signatures, we detail their application, experimental protocols, and integration into a cohesive workflow for statistical validation of behavioral outcomes. The ability to link specific, quantifiable neurobiological changes to behavior and treatment efficacy is a critical step toward precision medicine.

Core Machine Learning Methodologies

Support Vector Machines (SVM) for Brain Signature Classification

Support Vector Machines are powerful supervised learning models for classification and regression. In brain signature research, their primary strength lies in finding the optimal hyperplane that separates data from different classes (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) in a high-dimensional feature space, even when the relationship is non-linear.

- Core Principle and Kernel Trick: SVMs often employ the "kernel trick" to transform non-linearly separable data into a higher-dimensional space where a separating hyperplane can be found. Common kernels include Linear, Polynomial, and Radial Basis Function (RBF), with RBF being a popular default choice for its flexibility in capturing complex relationships.

- Application in Neuroscience: A landmark 2025 study demonstrated the use of SVM to identify distinct neuroanatomical signatures of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (CVM) in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Using structural MRI (sMRI) data from 37,096 participants, the developed SVM models quantified spatial patterns of atrophy and white matter hyperintensities related to specific risk factors like hypertension and diabetes. These models, collectively called SPARE-CVMs, outperformed conventional MRI markers with a ten-fold increase in effect sizes, capturing subtle patterns at sub-clinical stages [26].

- High-Accuracy Biomarker Identification: In psychiatric research, an SVM classifier was used to distinguish between schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) based on electrophysiological data from patient-derived brain cell models. The system achieved a classification accuracy of 95.8% for SCZ in two-dimensional cultures and 91.6% in 3D organoids, significantly outperforming the diagnostic agreement rates typically achieved through clinical interviews [27].

Table 1: Key SVM Studies on Brain Signatures

| Study Focus | Data Type & Sample Size | SVM Kernel & Performance | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|