Signature Models vs. Theory-Based Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of data-driven signature models and mechanism-driven theory-based models in biomedical research and drug development.

Signature Models vs. Theory-Based Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of data-driven signature models and mechanism-driven theory-based models in biomedical research and drug development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing methodologies from gene signature analysis to physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. The content addresses common challenges in model selection and application, offers frameworks for troubleshooting and optimization, and establishes rigorous standards for validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing insights from recent studies and established practices, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate modeling strategy for their specific research objectives, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and success of therapeutic development.

Core Principles: Understanding Signature and Theory-Based Models

Defining Data-Driven Signature Models in Drug Discovery

In the competitive landscape of drug discovery, the shift from traditional, theory-based models to data-driven signature models represents a paradigm change in how researchers uncover new drug-target interactions (DTIs). This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and practical applications to inform the work of researchers and drug development professionals.

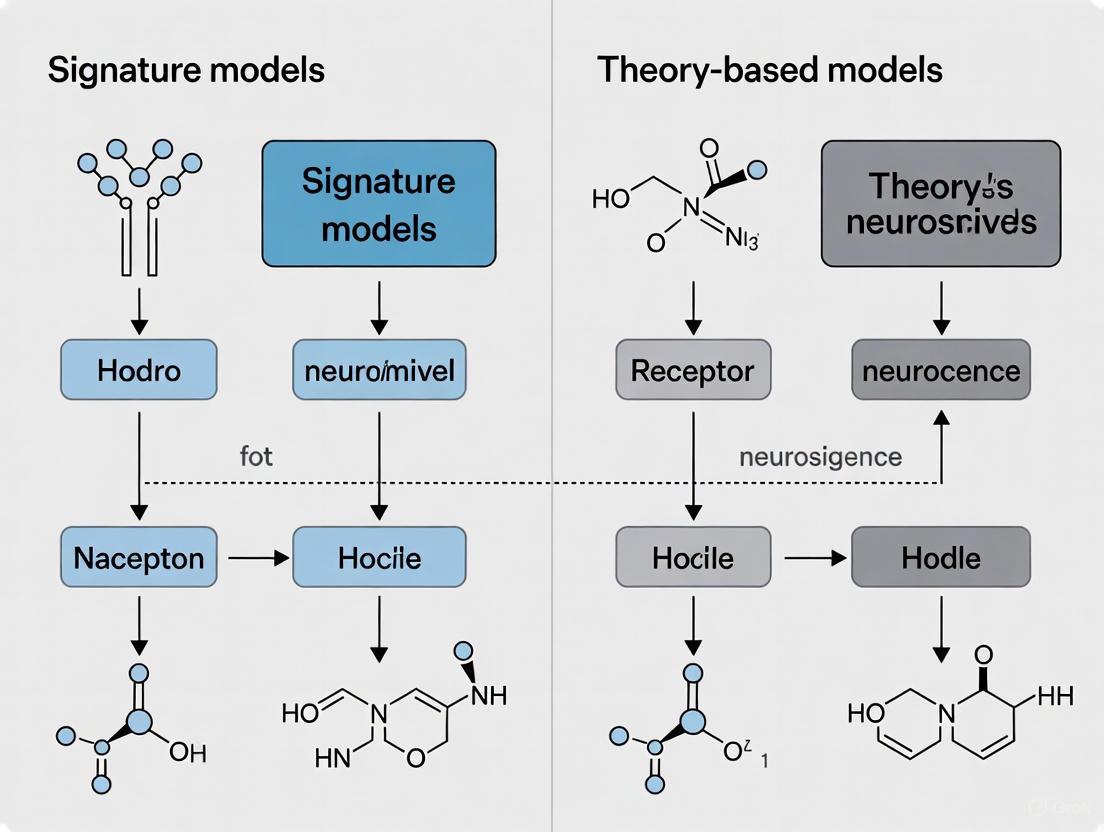

Model Paradigms: From Theory to Data

The following table contrasts the core philosophies of theory-based and data-driven signature models.

| Feature | Theory-Based (Physics/Model-Driven) | Data-Driven |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Established physical laws and first principles (e.g., Newton's laws, Navier-Stokes equations) [1] | Patterns and correlations discovered directly from large-scale experimental data [1] [2] |

| Problem Approach | Formulate hypothesis, then build a model based on scientific theory [2] | Use algorithms to find connections and correlations without pre-defined hypotheses [2] |

| Primary Strength | High interpretability and rigor for well-understood, linear phenomena [1] | Capability to solve complex, non-linear problems that are intractable for theoretical models [1] |

| Primary Limitation | Struggles with noisy data, unincluded variables, and system complexity; can be costly and time-consuming [1] [2] | Requires large amounts of data; can be a "black box" with lower interpretability [2] |

| Best Suited For | Systems that are well-understood and can be accurately described with simplified models [1] | Systems with high complexity and multi-dimensional parameters that defy clean mathematical description [1] |

Comparative Performance in Drug-Target Prediction

Objective comparisons reveal significant performance differences between various data-driven approaches and their theory-based counterparts. The table below summarizes quantitative results from key studies.

| Model / Feature Type | Key Performance Metric | Performance Summary | Context & Experimental Setup |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRoGS (Functional Representation) | Sensitivity in detecting shared pathway signals (Weak signal, λ=5) [3] | Superior ( -log(p) > ~300) | Outperformed Fisher's exact test and other embedding methods in simulated gene signature pairs with low pathway gene overlap [3]. |

| Pathway Membership (PM) | DTI Prediction Performance [4] | Superior | Consistently outperformed models using Gene Expression Profiles (GEPs); showed similar high performance to PPI network features when used in DNNs [4]. |

| PPI Network | DTI Prediction Performance [4] | Superior | Consistently outperformed models using GEPs; showed similar high performance to PM features in DNNs [4]. |

| Gene Expression Profiles (GEPs) | DTI Prediction Performance [4] | Lower | Underperformed compared to PM and PPI network features in DNN-based DTI prediction [4]. |

| DNN Models (using PM/PPI) | Performance vs. Other ML Models [4] | Superior | Consistently outperformed other machine learning methods, including Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, and Logistic Regression [4]. |

| DyRAMO (Multi-objective) | Success in avoiding reward hacking [5] | Effective | Successfully designed molecules with high predicted values and reliabilities for multiple properties (e.g., EGFR inhibition), including an approved drug [5]. |

The FRoGS Workflow: A Case Study in Data-Driven Enhancement

The Functional Representation of Gene Signatures (FRoGS) model exemplifies the data-driven advantage. It addresses a key weakness in traditional gene-identity-based methods by using deep learning to project gene signatures onto a functional space, analogous to word2vec in natural language processing. This allows it to detect functional similarity between gene signatures even with minimal gene identity overlap [3].

FRoGS creates a functional representation of gene signatures.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking FRoGS Performance

The experimental methodology for validating FRoGS against other models is detailed below [3].

- 1. Objective: To evaluate the sensitivity of FRoGS in detecting shared functional pathways between two gene signatures with weak signal overlap, compared to Fisher's exact test and other gene-embedding methods.

- 2. Data Simulation:

- A background gene set of 100 genes was created, containing no genes from a given pathway W.

- Two foreground gene sets were generated, each seeded with λ random genes from pathway W and the remaining 100-λ genes from outside W.

- The parameter λ was varied (e.g., 5, 10, 15) to modulate the strength of the pathway signal.

- 3. Model Comparison & Scoring:

- This sampling process was repeated 200 times for 460 human Reactome pathways.

- For each method, similarity scores were calculated for the foreground-foreground pair and the foreground-background pair.

- A one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine if the foreground-foreground similarity scores were statistically larger.

- 4. Key Outcome: FRoGS remained superior across the entire range of λ values, demonstrating a pronounced advantage in detecting weak pathway signals where traditional gene-identity-based methods (like Fisher's exact test) fail [3].

The table below lists key reagents, data sources, and computational tools essential for conducting research in this field.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| LINCS L1000 Dataset [3] [4] | Database | Provides a massive public resource of drug-induced and genetically perturbed gene expression profiles for building and testing signature models. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [3] | Knowledgebase | Provides structured, computable knowledge about gene functions, used for functional representation and pathway enrichment analysis. |

| MSigDB (C2, C5, H) [4] [6] | Gene Set Collection | Curated collections of gene sets representing known pathways, ontology terms, and biological states, used as input for pathway membership features and validation. |

| ARCHS4 [3] | Database | Repository of gene expression samples from public sources, used to proxy empirical gene functions for model training. |

| Polly RNA-Seq OmixAtlas [7] | Data Platform | Provides consistently processed, FAIR, and ML-ready biomedical data, enabling reliable gene signature comparisons across integrated datasets. |

| TensorFlow/Keras [4] | Software Library | Open-source libraries used for building and training deep neural network models for DTI prediction. |

| scikit-learn [4] | Software Library | Provides efficient tools for traditional machine learning (e.g., Random Forest, Logistic Regression) for baseline model comparison. |

| SUBCORPUS-100 MCYT [8] | Benchmark Dataset | A signature database used for objective performance benchmarking of models, particularly in verification tasks. |

Advanced Application: Overcoming Reward Hacking with DyRAMO

A significant challenge in data-driven molecular design is reward hacking, where generative models exploit imperfections in predictive models to design molecules with high predicted property values that are inaccurate or unrealistic [5]. The Dynamic Reliability Adjustment for Multi-objective Optimization (DyRAMO) framework provides a sophisticated solution.

DyRAMO dynamically adjusts reliability levels to prevent reward hacking.

DyRAMO's workflow integrates Bayesian optimization to dynamically find the best reliability levels for multiple property predictions, ensuring designed molecules are both high-quality and fall within the reliable domain of the predictive models [5].

The experimental data and comparisons presented in this guide unequivocally demonstrate the superior capability of data-driven signature models, particularly deep learning-based functional representations like FRoGS, in identifying novel drug-target interactions, especially under conditions of weak signal or high biological complexity. While theory-based models retain value for well-characterized systems, the future of drug discovery lies in the strategic integration of physical principles with powerful data-driven methods that can illuminate patterns and relationships beyond the scope of human intuition and traditional modeling alone.

Exploring Mechanism-Driven Theory-Based Models

A new modeling paradigm is emerging that combines theoretical rigor with practical predictive power across scientific disciplines.

In the face of increasingly complex scientific challenges, from drug development to industrial process optimization, researchers are moving beyond models that are purely theoretical or entirely data-driven. Mechanism-driven theory-based models represent a powerful hybrid approach, integrating first-principles understanding with empirical data to create more interpretable, reliable, and generalizable tools for discovery and prediction. This guide examines the performance and methodologies of these models across diverse fields, providing a comparative analysis for researchers and scientists.

Defining the Paradigm: Mechanism and Theory in Modeling

Before comparing specific models, it is essential to define the core concepts. A theory is a set of generalized statements, often derived from abstract principles, that explains a broad phenomenon. In contrast, a model is a purposeful representation of reality, often applying a theory to a particular case with specific initial and boundary conditions [9].

Mechanism-driven theory-based models sit at this intersection. They are grounded in the underlying physical, chemical, or biological mechanisms of a system (the theory), which are then formalized into a computational or mathematical framework (the model) to make quantitative predictions.

The impetus for this approach is the limitation of purely data-driven methods, which can struggle with interpretability, overfitting, and performance when data is scarce or lies outside trained patterns [10] [11]. Similarly, mechanistic models alone may fail to adapt to changing real-world conditions due to their reliance on precise, often idealized, input parameters [12]. The hybrid paradigm aims to leverage the strengths of both.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables summarize the performance of various mechanism-driven theory-based models against alternative approaches in different applications.

Table 1: Performance in Industrial and Engineering Forecasting

| Field / Application | Model Name | Key Comparator(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Result Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petroleum Engineering (Oil Production Forecasting) [12] | Mechanism-Data Fusion Global-Local Model | Autoformer, DLinear | MSE: Reduced by 0.0100 vs. AutoformerMAE: Reduced by 0.0501 vs. AutoformerRSE: Reduced by 1.40% vs. Autoformer | Superior accuracy by integrating three-phase separator mechanistic data as a constraint. |

| Process Industry (Multi-condition Processes) [11] | Mechanism-Data-Driven Dynamic Hybrid Model (MDDHM) | PLS, DiPLS, ELM, FNO, PIELM | Higher Accuracy & Generalization: Outperformed pure data-driven and other hybrid models across three industrial datasets. | Effectively handles dynamic, time-varying systems with significant distribution differences across working conditions. |

Table 2: Performance and Characteristics in Biomedical & Behavioral Sciences

| Field / Application | Model Name / Approach | Key Characteristics & Contributions | Data Requirements & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Development [13] | AI-Integrated Mechanistic Models | Combines AI's pattern recognition with the interpretability of mechanistic models. Enhances understanding of disease mechanisms, PK/PD, and enables digital twins. | Requires high-quality multi-omics and clinical data. Challenging to scale and estimate parameters. |

| Computational Psychiatry (Drug Addiction) [14] | Theory-Driven Computational Models (e.g., Reinforcement Learning) | Provides a quantitative framework to infer psychological mechanisms (e.g., impaired control, incentive sensitization). | Must be informed by psychological theory and clinical data. Risk of being overly abstract without clinical validation. |

| Preclinical Drug Testing [15] | Bioengineered Human Disease Models (Organoids, Organs-on-Chips) | Bridges the translational gap of animal models. High clinical biomimicry improves predictability of human responses. | Requires stringent validation and scalable production. High initial development cost. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a deeper understanding of the cited experiments, here are the detailed methodologies.

Protocol 1: Failure Causality Modeling in Mechanical Systems

This protocol is based on a novel approach that integrates Causal Ordering Theory (COT) with Ishikawa diagrams [10].

- 1. Problem Formulation: Define the specific mechanical failure mode to be investigated (e.g., excessive vibration in a bearing).

- 2. System Representation as a Structure: Represent the mechanical system as a self-contained set of algebraic equations,

E, where|E| = |v(E)|(the number of equations equals the number of variables). These equations are derived from the physics of the system (e.g., equilibrium relations, motion parameters). - 3. Causal Ordering Analysis:

- Decomposition: Partition the structure

Einto minimal self-contained subsets (Es) and a remaining subset (Ei). This is the0thderivative structure. - Iterative Substitution: For the

1stderivative structure, substitute the variables solved inEsinto the equations ofEi. This new structure is then itself partitioned into minimal self-contained subsets. - Cause Identification: Repeat the process iteratively to derive

k-thcomplete subsets. Following Definitions 5 and 6 from the research [10], variables solved in a lower-order subset are identified as exogenous (direct causes) of the endogenous variables solved in the subsequent higher-order subset.

- Decomposition: Partition the structure

- 4. Ishikawa Diagram Representation: Convert the abstract parametric causal relationships identified via COT into a practical cause-effect diagram (Ishikawa or fishbone diagram). This maps the root causes to the final failure event in a visually intuitive format for diagnostics.

- 5. Validation: The completeness and accuracy of the resulting causality network are evaluated through practical engineering case studies, demonstrating a reduced reliance on empirical knowledge and historical data [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this integrated causal analysis process:

Protocol 2: Hybrid Modeling for Multi-Condition Industrial Processes

This protocol outlines the MDDHM method for building a soft sensor in process industries [11].

- 1. Data Acquisition and Feature Extraction: Collect historical and current operational data from the industrial site. Process this data through a hidden layer with random weights to extract relevant features.

- 2. Mechanism-Based Value Calculation:

- Identify the Partial Differential Equation (PDE) representing the physical model of the process (e.g., from mass/energy conservation).

- Discretize and approximate the PDE using a numerical method (e.g., the forward Euler method).

- Compute the mechanism-based values for the quality variable of interest.

- 3. Dynamic Data Fusion:

- Fuse the mechanism-based values with real historical measurement data through a weighted mix.

- This fusion creates a new, hybrid label (quality variable) for regression that is informed by both theory and reality.

- 4. Dynamic Regression with Domain Adaptation:

- Under the framework of Dynamic inner Partial Least Squares (DiPLS), regress the extracted features against the newly created hybrid labels.

- Introduce a domain adaptation regularization term to the loss function. This term minimizes the distribution discrepancy between data from different working conditions, forcing the model to learn features that are robust to these changes.

- 5. Prediction: The trained model outputs the predicted value for the current working condition, benefiting from both mechanistic understanding and data-driven adaptation.

The following diagram visualizes this hybrid modeling workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomedical & Engineering Models

| Item | Function / Application | Field |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [15] | Foundational cell source for generating human organoids and bioengineered tissue models that recapitulate disease biology. | Biomedicine |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM) [15] | Used as a bioink to provide a natural, tissue-specific 3D scaffold that supports cell growth and function in bioprinted models. | Biomedicine, Bioengineering |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Devices [15] | Platforms that house human cells in a controlled, dynamic microenvironment to emulate organ-level physiology and disease responses. | Biomedicine, Drug Development |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Software (e.g., Simcyp, Gastroplus) [16] | Implements PBPK equations to simulate drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, improving human PK prediction. | Drug Development |

| Three-Phase Separator Mechanistic Model [12] | A physics-based model of oil-gas-water separation equipment that generates idealized data to constrain and guide production forecasting algorithms. | Petroleum Engineering |

| Causal Ordering Theory Algorithm [10] | A computational method for analyzing a system of equations to algorithmically deduce causal relationships between variables without correlation-based inference. | Mechanical Engineering, Systems Diagnostics |

The evidence across disciplines consistently shows that mechanism-driven theory-based models can achieve a superior balance of interpretability and predictive accuracy. They reduce reliance on large, pristine datasets [10] and provide a principled way to incorporate domain knowledge, which is especially valuable in high-stakes fields like drug development and engineering.

Future progress hinges on several key areas: the development of more sophisticated domain adaptation techniques to handle widely varying operational conditions [11], the creation of standardized frameworks and software to make complex hybrid modeling more accessible, and the rigorous validation of bioengineered disease models to firmly establish their predictive value in clinical translation [15]. As these challenges are met, mechanism-driven theory-based models are poised to become the cornerstone of robust scientific inference and technological innovation.

However, I can provide a framework and guidance on how to structure this work and where to find the necessary information.

Suggested Research Pathway for Your Article

To gather the required data, I recommend the following approaches:

- Utilize Specialized Databases: Search for primary research articles and reviews in databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. Use keywords such as "mechanistic vs empirical pharmacokinetic models," "comparison of quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) platforms," "PBPK model validation," and "theoretical frameworks in drug development."

- Analyze Software Documentation: The technical documentation, white papers, and case studies published by commercial modeling software providers (e.g., Certara, Simulations Plus, Open Systems Pharmacology) often contain detailed methodology and comparative performance data.

- Consult Regulatory Submissions: Public assessment reports from agencies like the FDA and EMA can provide real-world examples of how different models are applied and validated in the drug approval process.

Proposed Article Structure and Data Presentation

Based on your requirements, here is a structure for your article with examples of how to present information.

1. Structured Comparison Tables You can summarize the core assumptions of different model types in a table. The search results emphasize that choosing the right comparison method is crucial for clarity [17]. For instance:

| Model Type | Underlying Assumption | Primary Application | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down (Empirical) | System behavior can be described by analyzing overall output data without mechanistic knowledge. | Population PK/PD, clinical dose optimization. | Rich clinical data. |

| Bottom-Up (Mechanistic) | System behavior emerges from the interaction of defined physiological and biological components. | Preclinical to clinical translation, DDI prediction. | In vitro data, system-specific parameters. |

| QSP Models | Disease and drug effects can be modeled by capturing key biological pathways and networks. | Target validation, biomarker identification, clinical trial simulation. | Multi-scale data (e.g., -omics, cellular, physiological). |

2. Experimental Protocol Outline For a cited experiment comparing model predictive performance, your methodology section should detail:

- Software and Version: Specify the simulation environment and tools used.

- Virtual Population: Describe how the virtual patient population was generated (e.g., demographics, physiology, genotypes).

- Dosing Scenario: Define the drug, regimen, and system parameters used in the simulation.

- Comparison Metric: State the statistical metrics for comparison (e.g., fold error, RMSE, AIC).

3. Research Reagent Solutions Table Your "Scientist's Toolkit" should list the essential software and data resources.

| Item Name | Function in Model Development |

|---|---|

| PBPK Simulation Software | Platform for building, simulating, and validating physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models. |

| Clinical Data Repository | Curated database of in vivo human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data for model validation. |

| In Vitro Assay Kits | Provides critical parameters (e.g., metabolic clearance, protein binding) for model input. |

| Parameter Estimation Tool | Software algorithm to optimize model parameters to fit experimental data. |

I hope this structured guidance helps you compile the necessary data for your publication. If you are able to find specific datasets or model descriptions through your own research, I would be glad to help you analyze and format them into the required tables and diagrams.

Gene signatures—sets of genes whose collective expression pattern is associated with biological states or clinical outcomes—have evolved from exploratory research tools to fundamental assets in biomedical research and drug development. These signatures now play critical roles across the entire therapeutic development continuum, from initial target identification and patient stratification to prognostic prediction and therapy response forecasting [18]. The maturation of high-throughput technologies, coupled with advanced computational methods, has enabled the development of increasingly sophisticated signatures that capture the complex molecular underpinnings of disease. This guide provides a comparative analysis of gene signature approaches, focusing on their construction methodologies, performance characteristics, and applications in precision medicine, thereby offering researchers a framework for selecting and implementing these powerful tools.

Theoretical Frameworks: Comparing Signature Development Approaches

Gene signatures are developed through distinct methodological approaches, each with characteristic strengths and limitations. Understanding these foundational frameworks is essential for critical evaluation of signature performance and applicability.

Table 1: Comparison of Signature Development Approaches

| Approach | Description | Strengths | Limitations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Driven (Top-Down) | Identifies patterns correlated with clinical outcomes without a priori biological assumptions [19]. | Discovers novel biology; purely agnostic | May lack biological interpretability; lower reproducibility | 70-gene (MammaPrint) and 76-gene prognostic signatures for breast cancer [19] [20]. |

| Hypothesis-Driven (Bottom-Up) | Derives signatures from known biological pathways or predefined biological concepts [19]. | Strong biological plausibility; more interpretable | Constrained by existing knowledge; may miss novel patterns | Gene expression Grade Index (GGI) based on histological grade [19]. |

| Network-Integrated | Incorporates molecular interaction networks (PPIs, pathways) into signature development [20]. | Enhanced biological interpretability; improved stability | Dependent on completeness and quality of network data | Methods using protein-protein interaction networks to identify discriminative sub-networks [20]. |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Integrates data from multiple molecular layers (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) [21] [22]. | Comprehensive view of biology; captures complex interactions | Computational complexity; data harmonization challenges | 23-gene signature integrating 19 PCD pathways and organelle functions in NSCLC [21]. |

The emerging trend emphasizes platform convergence, where different technologies validate and complement each other to create more robust signatures [18]. For instance, transcriptomic findings supported by proteomic data and cellular assays provide stronger evidence for mechanistic involvement. Furthermore, the field is shifting toward multi-omics integration, combining data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and other molecular layers to achieve a more holistic understanding of disease mechanisms [22].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Signature Development and Validation

The construction of a robust gene signature follows a structured pipeline, from data acquisition to clinical validation. Below, we detail the core methodological components.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Data Sources: Most signature development begins with acquiring large-scale molecular data from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), or ArrayExpress [21] [23] [24]. These databases provide gene expression profiles (e.g., RNA-Seq, microarray data) alongside clinical annotations.

- Cohort Definition: Studies typically define a training cohort (e.g., TCGA-OV for ovarian cancer [24]) and one or more independent validation cohorts (e.g., GSE32062, GSE26193) to test generalizability [23] [24].

- Preprocessing: Raw data undergoes quality control, normalization (e.g., DESeq2 for RNA-Seq, log2(TPM+1) transformation [25]), and batch effect correction to ensure technical variability does not confound biological signals.

Feature Selection and Signature Construction

This critical step reduces dimensionality to identify the most informative genes.

- Initial Filtering: Univariate analysis (Cox regression for survival outcomes [23] [24] or differential expression analysis [25]) identifies genes associated with the phenotype of interest.

- Multivariate Regularization: LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Cox regression is the most widely used method for refining gene lists and preventing overfitting [23] [24]. It applies a penalty that shrinks coefficients of less important genes to zero, retaining a parsimonious set of features. For example, this method yielded a 17-gene signature for osteosarcoma [23] and a 7-gene signature for ovarian cancer [24].

- Alternative Machine Learning Algorithms: Other methods include:

- Random Survival Forests (RSF): Used in combination with StepCox for the 23-gene NSCLC signature [21].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests: Often compared in classification problems [26] [25].

- Advanced Feature Selection: Techniques like Adaptive Bacterial Foraging (ABF) optimization combined with CatBoost have been used to achieve high predictive accuracy in colon cancer [26].

Model Validation and Performance Assessment

- Risk Stratification: A risk score is calculated for each patient using a formula based on gene expression and coefficients:

Risk score = Σ(Expi * βi)[23]. Patients are dichotomized into high- and low-risk groups using a median cut-off or optimized threshold. - Survival Analysis: Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank tests evaluates the signature's ability to separate survival curves (e.g., DMFS, OS) [19] [23].

- Performance Metrics:

- Time-Dependent ROC Analysis: Assesses predictive accuracy at specific time points (e.g., 3, 5, 10 years) [23].

- Concordance Index (C-index): Measures the model's overall discriminatory power [21].

- Hazard Ratios (HR): Quantifies the magnitude of difference in risk between groups from Cox regression models [19].

- Multivariate Cox Analysis: Determines whether the signature provides prognostic information independent of standard clinical variables like age and stage [24].

Functional and Clinical Interpretation

- Biological Interpretation: Enrichment analyses (GO, KEGG) are performed to uncover biological pathways and processes associated with the signature genes [23] [24].

- Immune Contexture: Signatures are often correlated with immune cell infiltration (using tools like CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE) and immune checkpoint expression to understand interactions with the tumor microenvironment [23] [25].

- Nomogram Construction: Combines the gene signature with clinical parameters to create a practical tool for individualized outcome prediction [24].

- Therapeutic Response Prediction: Signatures are tested for their ability to predict response to therapies, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, using datasets from clinical trials [21] [25].

Figure 1: Workflow for Gene Signature Development and Validation. The process involves sequential stages from data preparation to clinical interpretation, utilizing various feature selection methods.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Gene Signatures Across Cancers

Direct comparison of signature performance reveals considerable variation in predictive power, gene set size, and clinical applicability across different malignancies and biological contexts.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Gene Signatures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Signature Description | Signature Size (Genes) | Performance Metrics | Validation Cohort(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Multi-omics signature integrating PCD pathways and organelle functions [21]. | 23 | C-index: Not explicitly reported; AUC range: 0.696-0.812 [21]. | Four independent GEO cohorts (GSE50081, GSE29013, GSE37745) [21]. |

| Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma (mUC) | Immunotherapy response predictor developed via transfer learning [25]. | 49 | AUC: 0.75 in independent test set [25]. | PCD4989g(mUC) dataset (n=94) [25]. |

| Ovarian Cancer | Prognostic signature based on tumor stem cell-related genes [24]. | 7 | Robust performance across multiple platforms; independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis [24]. | GSE32062, GSE26193 [24]. |

| Osteosarcoma | Prognostic signature identified from transcriptomic data [23]. | 17 | Significant stratification of survival (Kaplan-Meier, p<0.05); independent prognostic value [23]. | GSE21257 (n=53) [23]. |

| Colon Cancer | Multi-targeted therapy predictor using ABF-CatBoost [26]. | Not specified | Accuracy: 98.6%, Specificity: 0.984, Sensitivity: 0.979, F1-score: 0.978 [26]. | External validation datasets (unspecified) [26]. |

| Breast Cancer | 70-gene, 76-gene, and GGI signatures [19]. | 70, 76, 97 | Similar prognostic performance despite limited gene overlap; added significant information to classical parameters [19]. | TRANSBIG independent validation series (n=198) [19]. |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that smaller signatures (e.g., the 7-gene signature in ovarian cancer) can achieve robust performance validated across independent cohorts, highlighting the power of focused gene sets [24]. In contrast, more complex signatures (e.g., the 49-gene signature in mUC) address challenging clinical problems like immunotherapy response prediction, where biology is inherently more complex [25]. Notably, even signatures developed for the same cancer type (e.g., breast cancer) with minimal gene overlap can show comparable prognostic performance, suggesting they may capture core, convergent biological themes [19].

Successful development and implementation of gene signatures rely on a suite of well-established bioinformatic tools, databases, and analytical techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Signature Research

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application in Signature Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic R Packages | "glmnet" [23], "survival" [23], "timeROC" [24], "clusterProfiler" [24], "DESeq2" [25] | Statistical modeling, survival analysis, enrichment analysis, differential expression. | Core analysis: LASSO regression, survival model fitting, functional annotation. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | LASSO [23] [24], Random Survival Forest (RSF) [21], SVM [25], CatBoost [26], ABF optimization [26]. | Feature selection, classification, regression. | Identifying predictive gene sets from high-dimensional data. |

| Molecular Databases | TCGA [21] [24], GEO [21] [23], KEGG [20] [24], GO [20] [24], STRING [24], MitoCarta [21]. | Providing omics data, pathway information, protein-protein interactions. | Data sourcing for training/validation; biological interpretation of signature genes. |

| Immuno-Oncology Resources | CIBERSORT [21], ESTIMATE [21], xCell [21], TIDE [25], Immune cell signatures [25]. | Quantifying immune cell infiltration, predicting immunotherapy response. | Evaluating the immune contexture of signatures; developing immunotherapeutic biomarkers. |

| Visualization & Reporting Tools | "ggplot2", "pheatmap", "Cytoscape" [24], "rms" (for nomograms) [24]. | Data visualization, network graphing, clinical tool creation. | Generating publication-quality figures and clinical decision aids. |

Figure 2: The Platform Convergence Model for Robust Signature Development. Different technological platforms validate and complement each other, strengthening confidence in the final signature.

Gene signatures have fundamentally transformed the landscape of basic cancer research and therapeutic development. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that signature performance is not merely a function of gene set size but reflects the underlying biological complexity of the clinical question being addressed, the rigor of the feature selection methodology, and the robustness of validation. The field is moving beyond single-omics, data-driven approaches toward integrated multi-omics frameworks that offer deeper biological insights and greater clinical utility [27] [22].

Future developments will be shaped by several key trends. The integration of artificial intelligence with domain expertise will enable the discovery of subtle, non-linear patterns in high-dimensional data while ensuring signatures remain interpretable and actionable [27] [18]. The rise of single-cell and spatial multi-omics will provide unprecedented resolution for understanding tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment interactions [22]. Furthermore, an increased emphasis on technical feasibility and clinical portability will drive the simplification of complex discovery signatures into robust, deployable assays suitable for routine clinical trial conditions [18]. Ultimately, the successful translation of gene signatures into clinical practice will depend on this continuous interplay between technological innovation, biological understanding, and practical implementation, solidifying their role as indispensable tools in the era of precision medicine.

Theory-based models provide a foundational framework for understanding complex biological systems, from molecular interactions to whole-organism physiology. Unlike purely data-driven approaches that seek patterns from data alone, theory-based models incorporate established scientific principles, physical laws, and mechanistic understanding to explain and predict system behavior. In the field of systems biology, these models have emerged as essential tools to overcome the limitations of reductionist approaches, which struggle to explain emergent properties that arise from the integration of multiple components across different organizational levels [28]. The fundamental premise of theory-based modeling is that biological systems, despite their complexity, operate according to principles that can be mathematically formalized and computationally simulated.

The development of theory-based models represents a significant paradigm shift in biological research. Traditional molecular biology, embedded in the reductionist paradigm, has largely failed to explain the complex, hierarchical organization of living matter [28]. As noted in theoretical analyses of systems biology, "complex systems exhibit properties and behavior that cannot be understood from laws governing the microscopic parts" [28]. This recognition has driven the development of models that can capture non-linear dynamics, redundancy, disparate time constants, and emergence—hallmarks of biological complexity [29]. The contemporary challenge lies in integrating these multi-scale models to bridge the gap between molecular-level interactions and system-level physiology, enabling researchers to simulate everything from gene regulatory networks to whole-organism responses.

Comparative Analysis of Theory-Based Modeling Frameworks

Classification of Model Types by Application Domain

Table 1: Theory-Based Models Across Biological Scales

| Model Category | Representative Models | Primary Application Domain | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Physiology Models | HumMod, QCP, Guyton model | Integrative human physiology | Multi-system integration (~5000 variables), temporal scaling (seconds to years) | High complexity, requires extensive validation [29] |

| Network Physiology Frameworks | Network Physiology approach | Organ-to-organ communication | Captures dynamic, time-varying coupling between systems | Requires continuous multi-system recordings, complex analysis [30] |

| Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Models | PBPK, MBDD frameworks | Drug development & dosage optimization | Predicts full time course of drug kinetics, incorporates mechanistic understanding | Relies on accurate parameter estimation [16] |

| Hybrid Physics-Informed Models | MFPINN (Multi-Fidelity Physics-Informed Neural Network) | Specialized applications (e.g., foot-soil interaction in robotics) | Combines theoretical data with experimental validation, superior extrapolation capability | Domain-specific application [31] |

| Cellular Regulation Models | Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) | Cell-type-specific enhancer prediction | High predictive accuracy (93% correct cell type assignment), biologically interpretable | Limited to motif-driven regulatory elements [32] |

Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Theory-Based Models

| Model/Approach | Predictive Accuracy | Experimental Validation | Computational Efficiency | Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumMod | Simulates ~5000 physiological variables | Validated against clinical presentations (e.g., pneumothorax response) | 24-hour simulation in ~30 seconds | Comprehensive but human-specific [29] |

| Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) | 93% correct CRE assignment, auROC=0.98, auPR=0.98 | Synthetic enhancers validated cell-type-specific expression | Outperforms deep learning models with fewer parameters | Cross-species application (mouse, human, zebrafish, Arabidopsis) [32] |

| MFPINN | Superior interpolated and extrapolated generalization | Combines theoretical data with limited experimental validation | Higher cost-effectiveness than pure theoretical models | Suitable for extraterrestrial surface prediction [31] |

| PBPK Modeling | Improved human PK prediction over allometry | Utilizes drug-specific and system-specific properties | Implemented in specialized software (Simcyp, Gastroplus) | Broad applicability across drug classes [16] |

| Network Physiology | Identifies multiple coexisting coupling forms | Based on continuous multi-system recordings | Methodology remains computationally challenging | Framework applicable to diverse physiological states [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Developing Multi-Scale Physiological Models

The development of integrative physiological models like HumMod follows a systematic methodology for combining knowledge across biological hierarchies. The protocol involves several critical stages, beginning with the mathematical formalization of known physiological relationships from literature and experimental data. For the HumMod environment, this entails encoding hundreds of physiological relationships and equations in XML format, creating a framework of approximately 5000 variables that represent interconnected organs and systems [29]. The model architecture must accommodate temporal scaling, enabling simulations that range from seconds to years while maintaining physiological plausibility. Validation represents a crucial phase, where model predictions are tested against clinical presentations. For example, HumMod validation includes simulating known pathological conditions like pneumothorax and comparing the model's predictions of blood oxygen levels and cerebral blood flow responses to established clinical data [29]. This iterative process of development and validation ensures that the model captures essential physiological dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency—a fully integrated simulation parses approximately 2900 XML files in under 10 seconds and can run a 24-hour simulation in about 30 seconds on standard computing hardware [29].

Protocol for Hybrid Theory-Data Modeling

The Multi-Fidelity Physics-Informed Neural Network (MFPINN) methodology exemplifies a hybrid approach that strategically combines theoretical understanding with experimental data. The protocol begins with the identification of a physical theory that describes the fundamental relationships in the system—in the case of foot-soil interaction, this involves established bearing capacity theories [31]. The model architecture then incorporates this theoretical framework as a constraint on the neural network parameters and loss function, effectively guiding the learning process toward physically plausible solutions. The training process utilizes multi-fidelity data, combining large amounts of low-fidelity theoretical data with small amounts of high-fidelity experimental data. This approach alleviates the tension between accuracy and data acquisition costs that often plagues purely empirical models. The validation phase specifically tests interpolated and extrapolated generalization ability, comparing the MFPINN model against both pure theoretical models and purely data-driven neural networks. Results demonstrate that the physics-informed constraints significantly enhance generalization capability compared to models without such theoretical guidance [31].

Signaling Pathways and Model Architectures

Network Physiology Integration Framework

The Network Physiology framework illustrates how theory-based models integrate across multiple biological scales. This approach moves beyond studying isolated systems to focus on the dynamic, time-varying couplings between organ systems that generate emergent physiological states [30]. The architecture demonstrates both vertical integration (from molecular to organism level) and horizontal integration (dynamic coupling between systems), highlighting how theory-based models capture the fundamental principle that "coordinated network interactions among organs are essential to generating distinct physiological states and maintaining health" [30]. The framework addresses the challenge that physiological interactions occur through multiple forms of coupling that can simultaneously coexist and continuously change in time, representing a significant advancement over earlier circuit-based models that simply summed individual measurements from separate physiological experiments [30].

Model-Based Drug Development Workflow

The Model-Based Drug Development (MBDD) workflow demonstrates how theory-based models transform pharmaceutical development. This framework employs a network of inter-related models that simulate clinical outcomes from specific study aspects to entire development programs [16]. The approach begins with Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling that incorporates both drug-specific properties (tissue affinity, membrane permeability, enzymatic stability) and system-specific properties (organ mass, blood flow) to predict human pharmacokinetics more reliably than traditional allometric scaling [16]. The core "learn-confirm" cycle, a seminal concept in MBDD, uses models to continuously integrate information from completed studies to inform the design of subsequent trials [16]. Clinical trial simulation functions as a foundation for modern protocol development by simulating trials under various designs, scenarios, and assumptions, thereby providing operating characteristics that help understand how study design choices affect trial outcomes [16].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Theory-Based Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrative Physiology Platforms | HumMod, QCP, JSim | Provides modeling environments with thousands of physiological variables | Whole-physiology simulation, hypothesis testing [29] |

| Physiome Projects | IUPS Physiome Project, NSR Physiome Project | Develops markup languages and model repositories | Multi-scale modeling standards and sharing [29] |

| Drug Development Software | Simcyp, Gastroplus, PK-Sim/MoBi | Implements PBPK equations for human pharmacokinetic prediction | Early drug development, dose selection [16] |

| Regulatory Genomics | GimmeMotifs, BOM framework | Annotates and analyzes transcription factor binding motifs | Cell-type-specific enhancer prediction [32] |

| Materials Informatics | MatDeepLearn, Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network | Implements graph-based representation of material structures | Property prediction in materials science [33] |

| Experimental Databases | StarryData2 (SD2) | Systematically collects experimental data from published papers | Model validation and training data source [33] |

Discussion and Comparative Analysis

Integration of Theory-Based and Data-Driven Approaches

The comparative analysis of theory-based models reveals an emerging trend toward hybrid methodologies that leverage the strengths of both theoretical understanding and data-driven discovery. The Multi-Fidelity Physics-Informed Neural Network (MFPINN) exemplifies this approach, demonstrating how physical information constraints can significantly improve a model's generalization ability while reducing reliance on expensive experimental data [31]. Similarly, in materials science, researchers are developing frameworks to integrate computational and experimental datasets through graph-based machine learning, creating "materials maps" that visualize relationships in structural features to guide discovery [33]. These hybrid approaches address a fundamental challenge in biological modeling: the reconciliation of microscopic stochasticity with macroscopic order. As noted in theoretical analyses, "how to reconcile the existence of stochastic phenomena at the microscopic level with the orderly process finalized observed at the macroscopic level" represents a core question that hybrid models are uniquely positioned to address [28].

The Bag-of-Motifs (BOM) framework provides a particularly compelling example of how theory-based knowledge (in this case, the established understanding of transcription factor binding motifs) can be combined with machine learning to achieve superior predictive performance. Despite its conceptual simplicity, BOM outperforms more complex deep learning models in predicting cell-type-specific enhancers while using fewer parameters and offering direct interpretability [32]. This demonstrates that theory-based features, when properly incorporated, can provide strong inductive biases that guide learning toward biologically plausible solutions. The experimental validation of BOM's predictions—where synthetic enhancers assembled from predictive motifs successfully drove cell-type-specific expression—provides compelling evidence for the effectiveness of this hybrid approach [32].

Validation and Performance Across Domains

A critical assessment of theory-based models requires examination of their validation strategies and performance across different application domains. In integrative physiology, models like HumMod are validated through their ability to simulate known clinical presentations, such as the physiological response to pneumothorax, demonstrating accurate prediction of blood oxygen levels and cerebral blood flow responses [29]. In drug development, the value of model-based approaches is evidenced by their positive impact on decision-making processes across pharmaceutical companies, leading to the establishment of dedicated departments and specialized consulting services [16]. The quantitative performance metrics across domains show that theory-based models achieve remarkable accuracy when they incorporate appropriate biological constraints—BOM achieves 93% correct assignment of cis-regulatory elements to their cell type of origin, with area under the ROC curve of 0.98 [32].

A key advantage of theory-based models is their superior interpretability compared to purely data-driven approaches. The Bag-of-Motifs framework, for instance, provides direct biological interpretability by revealing which specific transcription factor motifs drive cell-type-specific predictions, enabling researchers to generate testable hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms [32]. This contrasts with many deep learning approaches in biology that function as "black boxes," making it difficult to extract mechanistic insights from their predictions. Similarly, Network Physiology provides interpretable frameworks for understanding how dynamic couplings between organ systems generate physiological states, moving beyond correlation to address causation in physiological integration [30].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Despite their demonstrated value, theory-based models face significant implementation challenges that must be addressed to advance their impact. In implementation science research for medicinal products, studies have shown inconsistent application of theories, models, and frameworks, with limited use throughout the research process [34]. Similar challenges exist across biological modeling domains, including the need for long-term, continuous, parallel recordings from multiple systems for Network Physiology [30], and the high computational demands of graph-based neural networks with large numbers of graph convolution layers [33]. Future developments require collaborative efforts across disciplines, as "future development of a 'Human Model' requires integrative physiologists working in collaboration with other scientists, who have expertise in all areas of human biology" [29].

The evolution of theory-based models points toward several promising directions. First, there is growing recognition of the need to model biological systems as fundamentally stochastic rather than deterministic, acknowledging that "protein interactions are intrinsically stochastic and are not 'directed' by their 'genetic information'" [28]. Second, models must better account for temporal dynamics, as physiological interactions continuously vary in time and exhibit different forms of coupling that may simultaneously coexist [30]. Third, there is increasing emphasis on making models more accessible and interpretable for experimental researchers, through tools like materials maps that visualize relationships in structural features [33]. As these developments converge, theory-based models will become increasingly powerful tools for bridging molecular interactions and system-level physiology, ultimately enabling more predictive and personalized approaches in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

In modern computational drug discovery, the concepts of drug-target networks (DTNs) and drug-signature networks (DSNs) provide complementary lenses through which to understand drug mechanisms. A drug-target network maps interactions between drugs and their protein targets, where nodes represent drugs and target proteins, and edges represent confirmed physical binding interactions quantified by affinity measurements such as Ki, Kd, or IC50 [35] [36]. In contrast, a drug-signature network captures the functional consequences of drug treatment, connecting drugs to genes that show significant expression changes following drug exposure, with edges weighted by differential expression scores [35] [37].

The fundamental distinction lies in their biological interpretation: DTNs reveal direct, physical drug-protein interactions, while DSNs reflect downstream transcriptional consequences. This case study examines the interplay between these networks through the theoretical framework of signature-based models, comparing their predictive performance, methodological approaches, and applications in drug repurposing and combination therapy prediction.

Theoretical Foundation: Signature-Based Models in Pharmacology

Signature-based modeling provides a mathematical framework for analyzing complex biological systems by representing biological states or perturbations as multidimensional vectors of features. In pharmacology, these signatures capture either structural signatures (based on drug chemical properties) or functional signatures (based on drug-induced cellular changes) [38].

Theoretical work on signature-based models demonstrates their universality in approximating complex systems, with the capacity to learn parameters from diverse data sources [38]. In drug discovery, this translates to models that can integrate multiple data types—chemical structures, gene expression profiles, and protein interactions—to predict novel drug-target relationships and drug synergies.

Network pharmacology extends this approach by modeling the complex web of interactions between drugs, targets, and diseases, enabling the identification of multi-target therapies and the repurposing of existing drugs [39]. The integration of DTNs and DSNs within this framework provides a systems-level understanding of drug action that transcends single-target perspectives.

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols and Computational Approaches

Drug-Target Network Construction

Data Sources and Curation: High-confidence DTN construction begins with integrating data from multiple specialized databases. The HCDT 2.0 database exemplifies this approach, consolidating drug-gene interactions from nine specialized databases with stringent filtering criteria: binding affinity measurements (Ki, Kd, IC50, EC50) must be ≤10 μM, and all interactions must be experimentally validated in human systems [36]. Key data resources include BindingDB (353,167 interactions), ChEMBL, Therapeutic Target Database (530,553 interactions), and DSigDB (23,325 interactions) [36].

Validation Framework: Experimental validation of predicted drug-target interactions follows a multi-stage process. For example, in the evidential deep learning approach EviDTI, predictions are prioritized based on confidence estimates, then validated through binding affinity assays (Ki/Kd/IC50 measurements), followed by functional cellular assays and in vivo studies [40]. This hierarchical validation strategy ensures both binding affinity and functional relevance are confirmed.

Drug-Signature Network Construction

Transcriptomic Data Processing: DSN construction utilizes gene expression data from resources such as the LINCS L1000 database, which contains transcriptomic profiles from diverse cell lines exposed to various drugs [37]. Standard processing involves analyzing Level 5 transcriptomic signatures 24 hours after treatment with 10 μM drug concentration, the most common condition in the LINCS dataset [37].

Differential Expression Analysis: Two primary approaches generate drug signatures:

- Conventional Drug Signature: Compares gene expression between drug-treated and untreated conditions across a fixed cell line panel.

- Drug Resistance Signature: Compares gene expression between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cell lines, identified based on IC50 values relative to the median across all tested cell lines [37].

Network Integration: The resulting DSN is typically represented as a bipartite graph connecting drugs to signature genes, with edge weights corresponding to the magnitude and direction of expression changes [35].

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Metrics

Comprehensive benchmarking of drug-target prediction methods reveals significant variation in performance across algorithms and datasets. A 2025 systematic comparison of seven target prediction methods using a shared benchmark of FDA-approved drugs found substantial differences in recall, precision, and applicability to drug repurposing [41].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Drug-Target Prediction Methods

| Method | Type | Algorithm | Database | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolTarPred | Ligand-centric | 2D similarity | ChEMBL 20 | Highest effectiveness [41] |

| PPB2 | Ligand-centric | Nearest neighbor/Naïve Bayes/DNN | ChEMBL 22 | Multiple algorithm options [41] |

| RF-QSAR | Target-centric | Random forest | ChEMBL 20&21 | QSAR modeling [41] |

| TargetNet | Target-centric | Naïve Bayes | BindingDB | Diverse fingerprint support [41] |

| CMTNN | Target-centric | Neural network | ChEMBL 34 | Multitask learning [41] |

| EviDTI | Hybrid | Evidential deep learning | Multiple | Uncertainty quantification [40] |

Table 2: Model Performance on Benchmark DTI Datasets (Best Values Highlighted)

| Model | DrugBank ACC (%) | Davis AUC (%) | KIBA AUC (%) | Uncertainty Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EviDTI | 82.02 | 96.1 | 91.1 | Yes [40] |

| TransformerCPI | 80.15 | 96.0 | 91.0 | No [40] |

| MolTrans | 78.94 | 95.7 | 90.8 | No [40] |

| GraphDTA | 76.33 | 95.2 | 90.3 | No [40] |

| DeepConv-DTI | 74.81 | 94.8 | 89.9 | No [40] |

For drug synergy prediction, models incorporating drug resistance signatures (DRS) consistently outperform conventional approaches. A 2025 study evaluating machine learning models on five drug combination datasets found that DRS features improved prediction accuracy across all algorithms [37].

Table 3: Drug Synergy Prediction Performance with Different Signature Types

| Model | Signature Type | Average AUROC | Average AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | Drug Resistance Signature | 0.824 | 0.801 |

| LASSO | Conventional Drug Signature | 0.781 | 0.762 |

| Random Forest | Drug Resistance Signature | 0.836 | 0.819 |

| Random Forest | Conventional Drug Signature | 0.792 | 0.778 |

| XGBoost | Drug Resistance Signature | 0.845 | 0.828 |

| XGBoost | Conventional Drug Signature | 0.803 | 0.789 |

| SynergyX (DL) | Drug Resistance Signature | 0.861 | 0.843 |

| SynergyX (DL) | Conventional Drug Signature | 0.821 | 0.804 |

Comparative Analysis: Structural vs. Functional Network Perspectives

Biological Interpretation and Functional Segregation

Analysis of the cellular components, biological processes, and molecular functions associated with DTNs and DSNs reveals striking functional segregation. Genes in drug-target networks predominantly encode proteins located in outer cellular zones such as receptor complexes, voltage-gated channel complexes, synapses, and cell junctions [35]. These genes are involved in catabolic processes of cGMP and cAMP, transmission, and transport processes, functioning primarily in ion channels and enzyme activity [35].

In contrast, genes in drug-signature networks typically encode proteins located in inner cellular zones such as nuclear chromosomes, nuclear pores, and nucleosomes [35]. These genes are involved in gene transcription, gene expression regulation, and DNA replication, functioning in DNA, RNA, and protein binding [35]. This spatial and functional separation underscores the complementary nature of both networks.

Network Topology and Hub Characteristics

The topology of DTNs and DSNs follows distinct patterns. Analysis of degree distributions reveals that both networks exhibit scale-free and power-law distributions, but with an inverse relationship: genes highly connected in DTNs are rarely hubs in DSNs, and vice versa [35]. This mutual exclusivity extends to transcription factor binding, with DSN-associated genes showing approximately three-fold higher TF binding frequency (six times per gene on average) compared to DTN-associated genes (two times per gene on average) [35].

Core gene analysis using peeling algorithms further highlights these topological differences. In m-core decomposition, DTNs typically contain 1-17 core gene groups, while DSNs contain 1-36 core gene groups, indicating greater connectivity in signature networks [35].

Network Architecture Comparison: This diagram illustrates the distinct data sources, gene types, and biological processes characterizing drug-target versus drug-signature networks, culminating in integrative applications.

Integrated Applications: Synergistic Use of Dual Networks

Drug Repurposing and Polypharmacology

The integrated analysis of DTNs and DSNs enables systematic drug repurposing by identifying novel therapeutic connections. A pharmacogenomic network analysis of 124 FDA-approved anticancer drugs identified 1,304 statistically significant drug-gene relationships, revealing previously unknown connections that provide testable hypotheses for mechanism-based repurposing [42]. The study developed a novel similarity coefficient (B-index) that measures association between drugs based on shared gene targets, overcoming limitations of conventional chemical similarity metrics [42].

Case studies demonstrate the power of this integrated approach. For example, MolTarPred predictions suggested Carbonic Anhydrase II as a novel target of Actarit (a rheumatoid arthritis drug), indicating potential repurposing for hypertension, epilepsy, and certain cancers [41]. Similarly, fenofibric acid was identified as a potential THRB modulator for thyroid cancer treatment through target prediction methods [41].

Drug Combination Synergy Prediction

Integrating drug resistance signatures significantly improves drug combination synergy prediction. A 2025 study demonstrated that models incorporating DRS features consistently outperformed traditional structure-based approaches across multiple machine learning algorithms and deep learning frameworks [37]. The improvement was consistent across diverse validation datasets including ALMANAC, O'Neil, OncologyScreen, and DrugCombDB, demonstrating robust generalizability [37].

The workflow for resistance-informed synergy prediction involves:

- Cell Line Stratification: Grouping cell lines from GDSC database as sensitive or resistant based on IC50 values relative to median

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identifying genes significantly differentially expressed between sensitive and resistant groups

- Feature Integration: Incorporating DRS features with chemical descriptors and genomic features

- Model Training: Applying ensemble methods or deep learning frameworks to predict synergy scores [37]

This approach captures functional drug information in a biologically relevant context, moving beyond structural similarity to address specific resistance mechanisms.

Integrated Workflow: This diagram outlines the synergistic use of structural and functional data sources through computational methods to generate applications in drug repurposing, combination therapy, and safety prediction.

Table 4: Key Research Resources for Network Pharmacology Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Use | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCDT 2.0 | Database | Drug-target interactions | 1.2M+ curated interactions; multi-omics integration [36] |

| LINCS L1000 | Database | Drug signatures | Transcriptomic profiles for ~20,000 compounds [37] |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactivity data | 2.4M+ compounds; 20M+ bioactivity measurements [41] |

| DrugBank | Database | Drug information | Comprehensive drug-target-disease relationships [39] |

| MolTarPred | Software | Target prediction | Ligand-centric; optimal performance in benchmarks [41] |

| EviDTI | Software | DTI prediction | Uncertainty quantification; multi-modal integration [40] |

| Cytoscape | Software | Network visualization | Network analysis and visualization platform [39] |

| STRING | Database | Protein interactions | Protein-protein interaction networks [39] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that drug-target and drug-signature networks provide complementary perspectives on drug action, with distinct methodological approaches, performance characteristics, and application domains. While DTNs excel at identifying direct binding interactions and elucidating primary mechanisms of action, DSNs capture the functional consequences of drug treatment and adaptive cellular responses.

The integration of both networks within a signature-based modeling framework enables more accurate prediction of drug synergies, identification of repurposing opportunities, and understanding of resistance mechanisms. Future directions include the development of dynamic network models that capture temporal patterns of drug response, the incorporation of single-cell resolution signatures, and the application of uncertainty-aware deep learning models to prioritize experimental validation.

As network pharmacology evolves, the synergistic use of structural and functional signatures will increasingly guide therapeutic development, bridging traditional reductionist approaches with systems-level understanding of complex diseases.

Implementation in Practice: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Gene signature models are computational or statistical frameworks that use the expression levels of a specific set of genes to predict biological or clinical outcomes. These models have become indispensable tools in modern biomedical research, particularly in oncology, for tasks ranging from prognostic stratification to predicting treatment response. The core premise underlying these models is that complex cellular states, whether reflecting disease progression, metastatic potential, or drug sensitivity, are encoded in reproducible patterns of gene expression. By capturing these patterns, researchers can develop biomarkers with significant clinical utility.

The development of these models typically follows a structured pipeline: starting with high-dimensional transcriptomic data, proceeding through feature selection to identify the most informative genes, and culminating in the construction of a predictive model whose performance must be rigorously validated. A critical concept in this field, as highlighted in the literature, is understanding the distinction between correlation and causation. A gene that is correlated with an outcome and included in a signature may not necessarily be a direct molecular target; it might instead be co-regulated with the true causal factor. This explains why different research groups often develop non-overlapping gene signatures that predict the same clinical endpoint with comparable accuracy, as each signature captures different elements of the same underlying biological pathway network [43] [44].

Foundational Methodologies for Model Construction

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The first step in constructing a robust gene signature model is the acquisition and careful preprocessing of transcriptomic data. Data is typically sourced from public repositories like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). For RNA-seq data, standard preprocessing includes log2 transformation of FPKM or TPM values to stabilize variance and approximate a normal distribution. Quality control measures are critical; these involve removing samples with excessive missing data, filtering out genes with a high proportion of zero expression values, and regressing out potential confounding factors such as patient age and sex [45]. For microarray data, protocols often include global scaling to normalize average signal intensity across chips and quantile normalization to eliminate technical batch effects [44] [46].

Core Workflow and Feature Selection

The following diagram illustrates the standard end-to-end workflow for building and validating a gene signature model.

Feature selection is a critical step to identify the most informative genes from thousands of candidates. Multiple computational strategies exist for this purpose:

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): This systems biology method identifies modules of highly co-expressed genes and correlates their summary profiles (eigengenes) with clinical traits. Genes with high module membership within trait-relevant modules are considered hub genes and strong candidates for a signature [45].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Tools like the

limmapackage can identify genes whose expression differs significantly between sample groups. The criteria often involve an absolute log2-fold-change > 0.5 and a p-value < 0.05 [47]. - LASSO Regression: This technique performs both variable selection and regularization by applying a penalty that shrinks the coefficients of non-informative genes to zero, retaining only the most powerful predictors [47].

- Genetic Algorithms (GA): For complex phenotypes, GAs provide a powerful search heuristic. They work by iteratively evolving a population of candidate gene subsets over hundreds of generations, selecting for combinations that maximize predictive accuracy in machine learning classifiers [48].

Model Building and Validation Frameworks

Once a gene set is identified, a model is built to relate the gene expression data to the outcome of interest. The choice of algorithm depends on the nature of the outcome. For continuous outcomes, linear regression is common. For survival outcomes, Cox regression is standard, often in a multi-step process involving univariate analysis followed by multivariate analysis to build a final model [45] [47]. The output is a risk score, typically calculated as a weighted sum of the expression values of the signature genes.

Validation is arguably the most critical phase. The literature strongly emphasizes that performance metrics derived from the same data used for training are optimistically biased. Proper validation strategies are hierarchical:

- Internal Validation: Methods like 10-fold cross-validation or bootstrap validation provide initial, unbiased performance estimates during model development [43] [21].

- External Validation: The gold standard is testing the model's performance on a completely independent dataset, which assesses its generalizability to different patient populations [43].

- Comparison with Established Models: A robust validation includes benchmarking against existing signatures in the same disease context, using metrics like the Concordance Index (C-index) or Area Under the Curve (AUC) to demonstrate comparative value [21].

The following conceptual diagram outlines this critical validation structure.

Performance Comparison of Signature Models

Gene signature models have been successfully applied across numerous cancer types, demonstrating robust predictive power for prognosis and therapy response. The table below summarizes the performance of several recently developed signatures.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Recent Gene Signature Models in Oncology

| Cancer Type | Signature Function | Number of Genes | Performance (AUC/C-index) | Key Algorithms | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | Predicts early-stage progression & survival | 8 | Avg. AUC: 75.5% (12, 18, 36 mos) | WGCNA, Combinatorial ROC | [45] |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Prognosis & immunotherapy response | 23 | AUC: 0.696-0.812 | StepCox[backward] + Random Survival Forest | [21] |

| Cervical Cancer (CESC) | Prognosis & immune infiltration | 2 | Effective Prognostic Stratification | LASSO + Cox Regression | [47] |

| Melanoma | Predicts autoimmune toxicity from anti-PD-1 | Not Specified | High Predictive Accuracy (Specific metrics not provided) | Sparse PLS + PCA | [46] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Predicts antibiotic resistance | 35-40 | Accuracy: 96-99% | Genetic Algorithm + AutoML | [48] |

The data reveals that high predictive accuracy can be achieved with signature sizes that vary by an order of magnitude, from a compact 2-gene signature in cervical cancer to a 40-gene signature for antibiotic resistance in bacteria. This suggests that the optimal number of genes is highly context-dependent. A key insight from comparative studies is that even signatures with minimal gene overlap can perform similarly if they capture the same underlying biology, as different genes may represent the same biological pathway [44].

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Detailed Protocol for a Prognostic Signature

The following step-by-step protocol is synthesized from multiple studies, particularly the 8-gene LUAD signature and the 23-gene multi-omics NSCLC signature [45] [21]:

- Cohort Definition and RNA Sequencing: Define a patient cohort with consistent clinical endpoint data. For the LUAD study, this was 461 TCGA samples with overall survival and staging data. Extract total RNA from tumor samples (e.g., using QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit for blood, or directly from tissue). Quality control with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Prepare libraries and sequence using an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Data Preprocessing: Process raw RNA-seq data (e.g., from TCGA GDC portal) to obtain FPKM or TPM values. Apply a log2 transformation. Filter out transcripts with ≥50% zero expression values and remove sample outliers based on connectivity metrics. Normalize microarray data (if used) with global scaling or quantile normalization.

- Identify Trait-Associated Modules with WGCNA: Construct a co-expression network using the WGCNA R package. Determine the soft-thresholding power (β) to achieve a scale-free topology. Identify modules of co-expressed genes using a blockwiseModules function. Correlate module eigengenes with clinical traits (e.g., survival, stage) using biweight midcorrelation (bicor). Select modules with the strongest associations for further analysis.

- Select Hub Genes and Build a Predictive Ratio: From the key modules, identify hub genes (e.g., top 10% by intramodular connectivity). Use iterative combinatorial ROC analysis to test different combinations and ratios of genes from anti-correlated modules. The top-performing model from the LUAD study was a ratio: (ATP6V0E1 + SVBP + HSDL1 + UBTD1) / (GNPNAT1 + XRCC2 + TFAP2A + PPP1R13L) [45].

- Validate the Model: Split the data into training and test sets, or use cross-validation. Apply the signature to the validation set and calculate performance metrics (AUC for time-dependent ROC, C-index for survival). For the highest level of evidence, validate the signature in one or more completely independent cohorts.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Gene Signature Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Products / Packages |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality total RNA from tissue or blood samples for sequencing. | QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit, RNAzol B [46] |

| Gene Expression Profiling Panel | Targeted measurement of a predefined set of genes, often used for validation. | NanoString nCounter PanCancer IO 360 Panel [46] |

| Public Data Repositories | Sources of large-scale, clinically annotated transcriptomic data for discovery and validation. | TCGA GDC Portal, GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) [45] [21] |

| WGCNA R Package | Constructs co-expression networks to identify modules of correlated genes linked to traits. | WGCNA v1.70.3 [45] |