Spatial Extent Replicability: Overcoming Model Fit Challenges in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article addresses the critical challenge of ensuring the replicability of model fit across varying spatial extents, a pivotal concern for researchers and drug development professionals.

Spatial Extent Replicability: Overcoming Model Fit Challenges in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of ensuring the replicability of model fit across varying spatial extents, a pivotal concern for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles defining spatial extent and its impact on result validity, drawing parallels from geospatial and environmental modeling. The piece systematically reviews methodological frameworks for defining spatial parameters, highlights common pitfalls that compromise replicability, and presents robust validation techniques. By integrating case studies from neuroimaging and clinical trial design, we provide a comprehensive guide for achieving reliable, generalizable spatial models in biomedical research, ultimately aiming to enhance the rigor and predictive power of quantitative analyses in drug development.

Defining the Problem: Why Spatial Extent is a Foundational Pillar for Replicable Model Fits

The Critical Impact of Spatial Extent on Model Output Accuracy and Completeness

Troubleshooting Guides

Why does my model's performance vary drastically when applied to a new geographic area?

Issue: A model trained and validated in one region performs poorly when applied to a different spatial extent, showing inaccurate predictions and unreliable species richness estimates.

Explanation: The reliability of geospatial models is highly dependent on the spatial extent used for training and validation [1]. Models trained on limited environmental variability often fail to generalize to new areas with different environmental conditions. Furthermore, the problem of spatial autocorrelation (SAC) can create deceptively high performance metrics during training that don't hold up in new locations [2].

Solution:

- Expand Training Diversity: Incorporate data from multiple spatial extents that collectively capture the full range of environmental conditions your model may encounter [1].

- Spatial Cross-Validation: Implement validation techniques that account for spatial clustering rather than using random train-test splits [2].

- Uncertainty Estimation: Always quantify and report prediction uncertainty, especially when applying models to new spatial extents [2].

How can I improve species richness predictions from stacked ecological niche models (ENMs) at different spatial scales?

Issue: Stacked ENMs consistently overpredict or underpredict species richness, particularly at smaller spatial extents.

Explanation: Stacked Ecological Niche Models tend to be poor predictors of species richness at smaller spatial extents because species interactions and dispersal limitations become more influential at local scales [1]. The accuracy generally improves with larger spatial extents that incorporate more environmental variability [1].

Solution:

- Extent Matching: Ensure the spatial extent of your analysis matches the ecological processes you're modeling. For reliable richness estimates, consider using coarser extents (75-100 km) [1].

- Taxonomic Group Consideration: Account for biological differences between taxonomic groups. Cactaceae models showed different error patterns (overprediction) compared to Pinaceae models (both over- and underprediction) [1].

- Environmental Heterogeneity: Include sufficient environmental variability in your training data to better discriminate between suitable and unsuitable habitats [1].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the minimum spatial extent required for reliable species richness modeling?

Research indicates that for reliable species richness estimates from stacked ENMs, spatial extents of approximately 75-100 kilometers provide more reliable results than smaller extents [1]. The relationship between observed and predicted richness improves noticeably with the size of spatial extents, though this varies by taxonomic group [1].

How does spatial autocorrelation affect my model's reported accuracy?

Spatial autocorrelation can create deceptively high predictive power during validation if not properly accounted for [2]. When training and test data are spatially clustered, traditional validation methods may indicate good performance that doesn't generalize to new areas. Proper spatial cross-validation techniques that separate spatially clustered data are essential for accurate performance assessment [2].

Why do models for different taxonomic groups perform differently at the same spatial extents?

Taxonomic groups with narrow environmental limits (like Cactaceae) often yield more accurate models than groups with wider environmental tolerances (like Pinaceae) [1]. Species with broad environmental limits are more difficult to model accurately due to partial knowledge of species presence and the limited number of environmental variables used as parameters [1].

Model Performance vs. Spatial Extent

| Spatial Extent Range | Cactaceae Model Reliability | Pinaceae Model Reliability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10² - 10³ ha | Poor predictors | Poor predictors | Strong overprediction for Cactaceae; both over- and underprediction for Pinaceae [1] |

| 10³ - 10⁴ ha | Low correlation with observed richness | Low correlation with observed richness | High influence of species interactions [1] |

| 10⁴ - 10⁵ ha | Improving correlation | Improving correlation | Decreasing effect of local species interactions [1] |

| 10⁵ - 10⁶ ha | Better reliability | Better reliability | Incorporation of more environmental variability [1] |

| 10⁶ - 10⁷ ha | Most reliable for richness estimates | Most reliable for richness estimates | Best environmental discrimination capacity [1] |

Taxonomic Group Modeling Characteristics

| Characteristic | Cactaceae | Pinaceae |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Niche | Narrow, warm arid regions [1] | Broad, subarctic to tropics [1] |

| Typical Modeling Error | Overprediction [1] | Both over- and underprediction [1] |

| Model Sensitivity | Higher [1] | Lower [1] |

| Model Specificity | Lower [1] | Higher [1] |

| Range Size Effect | More accurate for limited ranges [1] | Less accurate for broad ranges [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Methodology for Assessing Spatial Extent Impact on Stacked ENMs

Objective: Evaluate how spatial extent influences the reliability of species richness predictions from stacked ecological niche models for different taxonomic groups [1].

Data Collection:

- Floral Data: Collect species lists from published floras across a stratified random sample of spatial extents (10¹ to 10⁷ hectares) [1]

- Occurrence Data: Gather species occurrence records from biodiversity databases (e.g., GBIF) for target taxonomic groups [1]

- Environmental Predictors: Compile relevant environmental variables covering the study region [1]

Modeling Procedure:

- ENM Development: Generate ecological niche models for each species using occurrence data and environmental predictors [1]

- Model Stacking: Overlay potential distribution estimates for all species within each flora's bounding box [1]

- Richness Prediction: Sum binary or probabilistic predictions to generate species richness estimates [1]

- Performance Validation: Compare predicted richness against observed richness from published floras [1]

Analysis:

- Calculate correlation coefficients between observed and predicted richness across different spatial extents [1]

- Assess sensitivity and specificity of predictions for each taxonomic group [1]

- Evaluate systematic overprediction or underprediction trends [1]

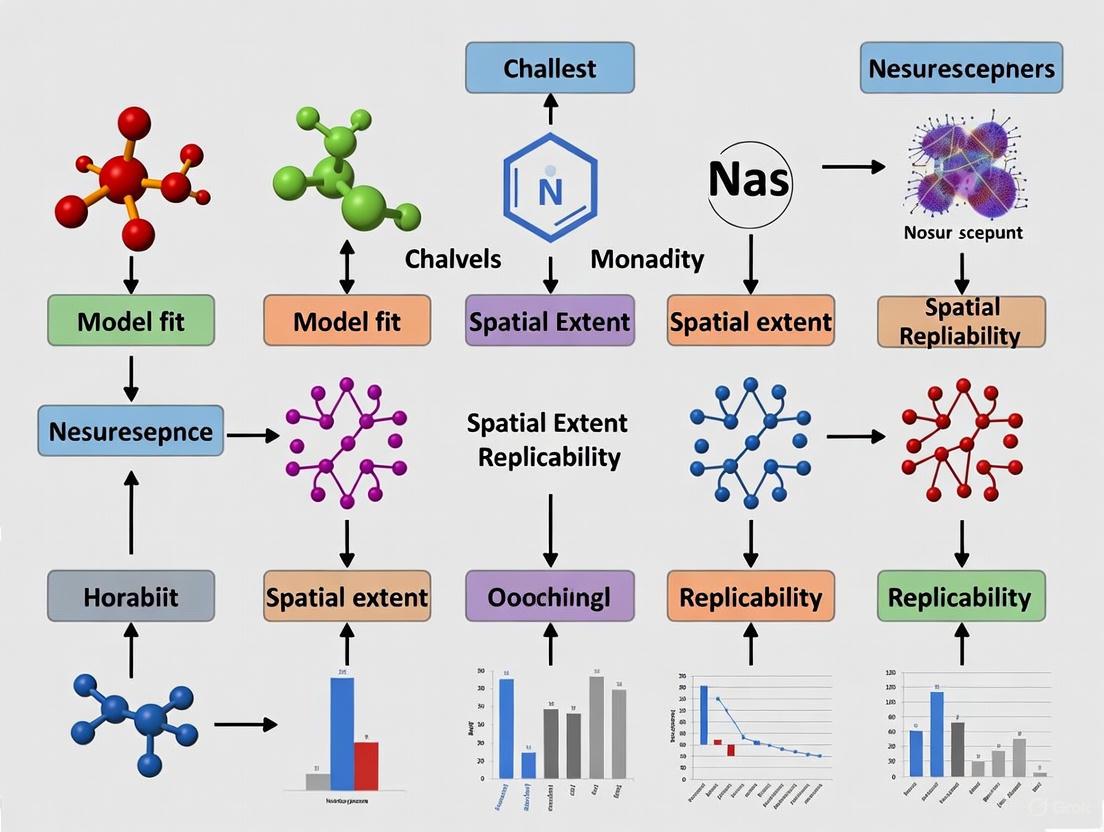

Workflow Visualization

Spatial Modeling Workflow: This diagram outlines the key steps in assessing spatial extent impacts on model accuracy, highlighting critical phases where spatial considerations must be addressed.

Data Challenges & Solutions: This diagram illustrates common spatial data challenges and their corresponding solutions, showing the relationship between problems and mitigation strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GBIF Data | Global biodiversity occurrence records [1] | Primary source for species occurrence points; requires quality filtering |

| Environmental Predictors | Bioclimatic and topographic variables [1] | Should represent relevant ecological gradients; resolution should match study extent |

| Ecological Niche Modeling Algorithms | MaxEnt, Random Forest, etc. [1] | Choice affects model transferability; multiple algorithms should be compared |

| Spatial Cross-Validation | Account for spatial autocorrelation [2] | Essential for realistic error estimation; use spatial blocking instead of random splits |

| Uncertainty Estimation Methods | Quantify prediction reliability [2] | Critical for model interpretation and application; should be reported for all predictions |

Understanding Spatial Autocorrelation and its Effect on Model Generalization

FAQ: Core Concepts

What is Spatial Autocorrelation? Spatial autocorrelation describes how the value of a variable at one location is similar to the values of the same variable at nearby locations. It is a mathematical expression of Tobler's First Law of Geography: "everything is related to everything else, but nearby things are more related than distant things" [3] [4]. Positive spatial autocorrelation occurs when similar values cluster together in space, while negative spatial autocorrelation occurs when dissimilar values are near each other [3] [4].

Why should researchers be concerned about its effect on model generalization? Spatial autocorrelation (SAC) violates the fundamental statistical assumption of independence among observations [3] [5]. When unaccounted for, it can lead to over-optimistic estimates of model performance, inappropriate model selection, and poor predictive power when the model is applied to new, independent locations [6]. This compromises the replicability of findings across different spatial extents [7] [6].

How does spatial autocorrelation lead to an inflated perception of model performance? In cross-validation, if the training and testing sets are spatially dependent, the model appears to perform well because it is essentially being tested on data that is similar to what it was trained on. One study on transfer functions demonstrated that when a spatially independent test set was used, the true root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) was approximately double the previously published, over-optimistic estimates [6]. This inflation occurs because the model internalizes the spatial structure rather than learning the true underlying relationship [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating SAC

Problem: Model performs well in cross-validation but fails on new spatial data.

This is a classic symptom of a model that has overfit to the spatial structure of the training data rather than learning the generalizable process of interest [6].

Diagnostic Steps:

Quantify SAC in your response variable and model residuals.

- Action: Calculate Global Moran's I for your original data and for the residuals of your fitted model.

- Interpretation: A significant Moran's I value in the residuals indicates that your model has not adequately captured the spatial pattern, leaving behind structured noise that harms generalization [5] [6]. The presence of SAC in the response variable alone does not necessarily indicate a problem, but its presence in the residuals does [5].

- Tools: Use the

Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran's I)tool in ArcGIS [8] or themoran.test()function in R with thespdeppackage [4].

Assess the scale of autocorrelation.

- Action: Create a spatial correlogram or a smoothed distance scatter plot to visualize how autocorrelation changes with distance [9] [5].

- Interpretation: This helps you understand the distance range over which observations influence each other, which is critical for designing appropriate mitigation strategies [5].

Test model scalability with a spatially independent hold-out set.

- Action: Instead of a random train-test split, hold out entire geographic regions (e.g., all data from a specific fire, watershed, or administrative district) for validation [7] [6].

- Interpretation: This provides a more realistic estimate of how your model will perform in a true generalization context. A study on wildfire prediction found this method crucial for evaluating real-world applicability [7].

Mitigation Strategies:

Increase Sample Spacing:

- Protocol: Systematically increase the distance between your training data points. This reduces the redundancy caused by SAC and provides a more robust test of the model's ability to capture the underlying process [7].

- Evidence: A wildfire prediction study showed that model accuracy declined with increased sample spacing, but the relationships identified by feature importance remained consistent, indicating the model was capturing real processes rather than just spatial noise [7].

Incorporate Spatial Structure Explicitly:

- Protocol: Use spatial regression models that directly model the dependency.

- Protocol: Use spatial filtering methods like Moran Eigenvector Spatial Filtering to create synthetic covariates that capture the spatial structure, which can then be included in a standard linear model [3].

Account for Spatial Heterogeneity:

- Protocol: Apply Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR). This technique allows the relationships between predictors and the response variable to vary across the study area, accounting for spatial non-stationarity [3].

Problem: Computational failure when calculating spatial autocorrelation for large datasets.

Large datasets can cause memory errors during spatial weights matrix creation, especially if the distance band results in features having tens of thousands of neighbors [10].

Solutions:

- Reduce the number of neighbors: Lower the

Distance Band or Threshold Distanceparameter so that no feature has an excessively large number of neighbors (e.g., aim for a maximum of a few hundred, not thousands) [10]. - Remove spatial outliers: A few distant features can force a very large default distance band. Create a selection set that excludes these outliers for the initial analysis [10].

- Use a spatial weights matrix file: For very large analyses (e.g., >5,000 features), pre-calculating a spatial weights matrix file (

.swm) can be more memory-efficient than using an ASCII file [8] [10].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing SAC's Impact

Protocol 1: Evaluating Model Scalability Across Spatial Regions

- Objective: To test whether a model trained in one region can generalize to a different, spatially independent region.

- Methodology:

- Partition your dataset into two or more distinct geographic regions (e.g., Region A and Region B).

- Train your model exclusively on data from Region A.

- Use the trained model to predict outcomes in Region B.

- Compare the performance metrics (e.g., R², RMSE) from the Region B prediction with the cross-validation performance from Region A.

- Interpretation: A significant drop in performance when predicting in Region B indicates that the model may have overfit to the local spatial context of Region A and lacks generalizability [7] [6].

Protocol 2: Incremental Sample Spacing Test

- Objective: To determine if model performance is driven by fine-scale spatial autocorrelation or by the underlying ecological/process-based relationships.

- Methodology:

- Start with your full, finely-spaced dataset and calculate a baseline model performance.

- Systematically thin your dataset by increasing the minimum allowable distance between any two sample points.

- Re-train and re-evaluate the model (using a consistent method like cross-validation) at each level of sample spacing.

- Monitor changes in overall performance and in the feature importance rankings.

- Interpretation: If performance declines sharply with increased spacing, the model is highly dependent on fine-scale SAC. If feature importance remains stable even as performance declines modestly, it suggests the model is capturing meaningful processes [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Solutions

Table 1: Essential Tools for Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Global Moran's I | A global metric to test for the presence and sign (positive/negative) of spatial autocorrelation across the entire dataset [3] [4]. | Values range from -1 to 1. Significance is tested via z-score/ p-value or permutation [8] [9]. |

| Spatial Weights Matrix (W) | Defines the neighborhood relationships between spatial units, which is fundamental to all SAC calculations [3] [4]. | Can be contiguity-based (e.g., Queen, Rook) or distance-based. The choice of conceptualization critically impacts results [3] [8]. |

| LISA (Local Indicators of Spatial Association) | A local statistic (e.g., Local Moran's I) to identify specific clusters of high or low values and spatial outliers [3] [9]. | Helps pinpoint where significant spatial clustering is occurring, decomposing the global pattern [3]. |

| Spatial Correlogram | A graph plotting autocorrelation (e.g., Moran's I) against increasing distance intervals [9] [5]. | Reveals the scale or range at which spatial dependence operates, informing an appropriate distance threshold [5]. |

| Spatial Regression Models (SAR, CAR) | Statistical models that incorporate spatial dependence directly into the regression framework, either in the dependent variable (SAR) or the errors (CAR) [3]. | Corrects for the bias in parameter estimates and standard errors that arises from ignoring SAC [3] [5]. |

Workflow Diagram for Diagnosis and Mitigation

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing issues related to spatial autocorrelation and selecting an appropriate mitigation strategy.

SAC Diagnosis and Mitigation Workflow

FAQs: Spatial Extent and Model Replicability

Q1: What is the core problem with using a user-defined Area of Interest (AOI) as the spatial extent for all model inputs?

A1: The core problem is a fundamental mismatch between user-defined boundaries and the natural processes being modeled. Spatial processes are not bounded by user-assigned areas [11]. Using the AOI for all inputs ignores the spatial context required for accurate modeling. A classic example is extracting a stream network: using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) clipped only to the AOI, rather than the entire upstream catchment, will produce incorrect or incomplete results because it ignores the contributing area from upstream [11]. This introduces cascading errors, especially in workflows chaining multiple models.

Q2: How can improper spatial extents impact the replicability of my research findings?

A2: Improper spatial extents directly undermine replicability—the ability to obtain similar results using similar data and methods in a different spatial context [12]. This occurs due to spatial heterogeneity, where the expected value of a variable and the performance of models vary across the Earth's surface [12]. If a model's spatial extent does not properly account for this heterogeneity, findings become place-specific and cannot be reliably reproduced in other study areas, limiting their scientific and practical value.

Q3: What are the common symptoms of a cascading error caused by an improper spatial extent?

A3: You may encounter one or more of the following issues:

- Incomplete Results: The model runs but produces a physically implausible or truncated output, such as a river network that ends abruptly within the AOI [11].

- Biased Predictions: The model appears to work but shows systematically poor performance in certain areas because key driving variables are missing their full contextual scope [13].

- Poor Generalization: A model that is highly accurate in one region performs poorly when applied to a new region, even if the environmental conditions seem similar, due to unaccounted spatial heterogeneity [12] [13].

- Irreplicable Findings: Results from one study area cannot be reproduced in another, leading to a "replicability crisis" for spatial studies [12].

Q4: Beyond the DEM, what other data types commonly require a spatial extent different from the AOI?

A4:

- Meteorological Data: For spatial interpolation of variables like temperature, the extent must include not just stations within the AOI, but also nearby stations outside it to create a reliable interpolation field [11].

- Species Distribution Data: Modeling habitat suitability requires data from a region large enough to capture the full range of environmental conditions the species tolerates [13].

- Data for Distance Calculations: Inputs for deriving variables like "distance-to-river" require the source data (e.g., for river network extraction) to cover the entire upstream watershed that hydrologically influences the AOI [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Spatial Extent Errors

Problem: My geographical model workflow executes without crashing, but the output is physically implausible or cannot be replicated in a different study area.

| Step | Action | Key Questions to Ask | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnosis | Identify the specific model in your workflow producing suspicious output. Trace its inputs back to their source data. | Is the output incomplete (e.g., rivers don't flow)? Does it ignore clear edge-influences? | Pinpoint the model and data layer where the error first manifests. [11] |

| 2. Input Analysis | For the identified model input, determine its required spatial context. | Does this input represent a process that extends beyond the AOI (e.g., water flow, species dispersal, atmospheric transport)? | A formalized rule defining the necessary spatial extent for the specific input. [11] |

| 3. Workflow Correction | Apply knowledge rules to automatically adjust the input's spatial extent during workflow preparation. | Should the extent be a watershed, a buffer zone, a minimum bounding polygon, or a different ecological region? | An execution-ready workflow where inputs are automatically fetched at their correct, process-based extents. [11] |

| 4. Validation | Use a resampling and spatial smoothing framework (e.g., MESS) to test the sensitivity of your results to zoning and scale. | How consistent are my results if the analysis grain or boundary placement changes slightly? | A robust understanding of how spatial context affects your findings, improving the interpretability and potential replicability of your results. [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Spatial Validation

The following protocol, based on the Macro-Ecological Spatial Smoothing (MESS) framework, helps diagnose and overcome the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP), a core challenge for replicability [14].

Objective: To standardize the analysis of spatial data from different sources or regions to facilitate valid comparison and synthesis, thereby assessing the replicability of patterns.

Methodology:

- Define the Spatial Grain (

s): Select the size for the sampling regions (moving windows) that will slide across your landscape. - Set Sampling Parameters:

ss: Specify the sample size (number of local sites) to be randomly drawn within each window.n: Specify the number of random subsamples to be drawn with replacement in each window.mn: Set the minimum number of local sites a window must contain to be included.

- Sliding Window Execution: Slide the moving window of size

sacross the entire landscape. - Resampling and Metric Calculation: For each window location that meets the minimum site requirement (

mn):- Draw

nrandom subsamples of sizess. - For each subsample, calculate your metrics of interest (e.g., β-diversity, γ-richness, mean α-richness, environmental heterogeneity).

- Retain the average value of these metrics across the

nsubsamples for that window.

- Draw

- Synthesis and Mapping: The averaged metric values for each window create a continuous surface of spatial pattern, sidestepping arbitrary zonation. This allows for direct, standardized comparison between different studies or regions [14].

The Spatial Workflow Logic: Problem vs. Solution

The following diagram illustrates the critical difference between a flawed, common approach and a robust, knowledge-driven methodology for handling spatial extents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Addressing Spatial Extent & Replicability |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Rule Base | A systematic formalization of how the spatial extent for a model input should be determined based on its semantic relation to the output and its data type. This is the core of intelligent spatial workflow systems [11]. |

| Macro-Ecological Spatial Smoothing (MESS) | A flexible R-based framework that uses a moving window and resampling to standardize datasets, allowing for inferential comparisons across landscapes and mitigating the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) [14]. |

| Place-Based (Idiographic) Analysis | An analytical approach focused on the distinct nature of places. It acknowledges spatial heterogeneity and is used when searching for universal, replicable laws (nomothetic science) is confounded by local context [12]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | A class of deep learning algorithms particularly adept at learning from spatial data. They can inherently capture spatial patterns and contexts, but their application must still consciously account for spatial heterogeneity to ensure replicability [12]. |

| Spatial Cross-Validation | A validation technique where data is split based on spatial location or clusters (rather than randomly). It is crucial for obtaining realistic performance estimates and testing a model's ability to generalize to new, unseen locations [13]. |

| Cloud-Based Data Platform (e.g., S3) | Provides the necessary processing capabilities and scalability to handle large geospatial file sizes and the computational demands of resampling, smoothing, and running complex spatial models [15]. |

| Uncertainty Estimation Metrics | Tools and techniques to quantify the certainty of model predictions. This is especially important when a model is applied in areas where the input data distribution differs from the training data (out-of-distribution problem) [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my spatial model perform well in one geographic area but fails in another, even for the same phenomenon?

This is a classic sign of the replicability challenge in spatial modeling, primarily driven by spatial heterogeneity. Spatial processes and the relationships between variables are not uniform across a landscape; they change from one location to another due to local environmental, social, or biological factors [16] [13]. A model trained in one region learns the specific relationships present in that data. When applied to a new area where these underlying relationships differ, the model's performance degrades because the fundamental rules it learned are no longer fully applicable.

FAQ 2: What is spatial autocorrelation, and how can it mislead my model's performance evaluation?

Spatial autocorrelation (SAC) is the concept that near things are more related than distant things, a principle often referred to as Tobler's First Law of Geography [17]. In modeling, SAC causes a violation of the common assumption that data points are independent. When training and test datasets are split randomly across a study area, they may not be truly independent if they are located near each other. This can lead to deceptively high predictive performance during validation because the model is effectively tested on data that is very similar to its training data, a problem known as spatial overfitting. Properly evaluating a model requires spatial validation techniques, such as splitting data by distinct spatial clusters or geographic regions, to ensure a realistic assessment of its performance on truly new, unseen locations [13] [16].

FAQ 3: My dataset has significant 'holes' or missing data in certain areas. How can I fill these gaps without biasing my results?

Filling missing data, or geoimputation, should be done with extreme caution. The best practice is to use the values of spatial neighbors, as guided by Tobler's Law [17]. However, this can introduce bias. Key considerations include:

- Amount of Missing Data: A common rule of thumb is to fill no more than 5% of the values in a dataset [17].

- Fill Method: The choice depends on your data and goal:

- Average of Neighbors: Use when values are expected to be similar to surroundings.

- Median of Neighbors: Preferred if outliers are suspected locally.

- Maximum of Neighbors: Use when you want to avoid underestimation (e.g., in public health risk mapping).

- Minimum of Neighbors: Use when you want a conservative estimate.

- Neighborhood Definition: You can define neighbors by a fixed distance, a fixed number of nearest features, or by contiguity (sharing a border) [17]. Always compare the data distribution (e.g., mean, standard deviation, histogram) before and after imputation to understand how your actions have altered the dataset.

FAQ 4: What is a "threshold parameter" in a spatial context, and why is it different from non-spatial models?

In classic non-spatial epidemic models, the basic reproductive number ( R_0 ) has a critical threshold of 1. However, in spatial models, this threshold is often higher. For example, in nearest-neighbour lattice models, the threshold value lies between 2 and 2.4 [18]. This is because spatial constraints and the local clustering of contacts change the dynamics of spread. An infected individual in a spatial model cannot contact all susceptible individuals in the population, only nearby ones, which reduces the efficiency of transmission and raises the transmissibility required for a large-scale outbreak [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fails to Generalize Across Geographic Regions

Symptoms:

- High accuracy in the original study area, poor accuracy in a new area.

- The spatial pattern of prediction errors is not random but clustered in the new region.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Step 1: Diagnose Spatial Heterogeneity

- Action: Conduct an exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) for both the original and new study areas.

- Method: Calculate local statistics (e.g., Local Indicators of Spatial Association - LISA) to map local relationships between your dependent and independent variables. If the relationships are visually and statistically different between the two regions, spatial heterogeneity is confirmed as a primary cause [16] [13].

- Toolkit: Software with ESDA capabilities (e.g., GeoDa, ArcGIS Pro, R with

spdeppackage).

Step 2: Assess and Account for Spatial Autocorrelation

- Action: Validate your model using a spatially-aware method.

- Method: Instead of a random train-test split, use a spatial cross-validation or block cross-validation approach. This involves training and testing the model on distinct geographic clusters or tiles, ensuring the model is evaluated on spatially independent data [13].

- Toolkit: The

blockCVR package or custom scripting in Python withscikit-learn.

Step 3: Quantify Replicability

- Action: Generate a "replicability map" [16].

- Method:

- Train your model on the original region.

- Apply it to a moving window across the entire domain of interest (e.g., a continent).

- For each window, calculate a performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score).

- Map this performance metric. The resulting replicability map visually reveals which geographic areas the model generalizes well to and where it fails, directly illustrating the challenge of user-defined bounds [16].

Problem: Unrealistic Model Predictions at the Edges of the Study Area

Symptoms:

- Sharp, unrealistic transitions in predicted values at the boundary of the area of interest.

- High prediction uncertainty for locations near the edge.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Step 1: Check for Edge Effects

- Action: Confirm the problem is an edge effect.

- Method: Visually inspect prediction maps. High uncertainty or clearly artificial patterns that align with the study boundary are key indicators. This happens because the model lacks contextual information from beyond the user-defined area [13].

Step 2: Incorporate a Spatial Buffer

- Action: Expand the data collection area to create a buffer.

- Method: When defining your study area, include a generous buffer zone around your core area of interest. Gather predictor variable data for this larger area. This provides the model with the necessary spatial context to make more realistic predictions near the edges of your core area. The buffer should be large enough to capture the spatial process's scale of influence.

Step 3: Model with Spatial Context

- Action: Use modeling techniques that explicitly incorporate spatial context.

- Method: Implement models that use spatial lag variables or deep learning models that can process the spatial context around each pixel or polygon (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks). This allows the model to "see" the neighborhood around a location, mitigating the edge effect.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Spatial Cross-Validation for Robust Model Evaluation

Objective: To accurately evaluate a spatial model's predictive performance and its potential to generalize to new, unseen locations.

Methodology:

- Define Spatial Blocks: Instead of randomly assigning data points to training and test sets, partition the study area into distinct spatial blocks or clusters. These can be regular tiles (e.g., quadrats) or irregular clusters based on k-means or spatial proximity [13].

- Iterative Training and Testing: Iteratively hold out one block as the test set and use all other blocks as the training set. This is repeated until each block has been used as the test set once.

- Aggregate Performance: Calculate the performance metric (e.g., R², RMSE, Accuracy) for each fold and then aggregate these (e.g., average) to get a final, spatially-robust performance estimate.

Interpretation: A model that performs well under spatial cross-validation is more likely to have captured the true underlying spatial process rather than just memorizing local spatial structure, giving greater confidence in its application to new areas.

Protocol: Conducting a Spatial Extension (Likelihood Ratio) Test

Objective: To statistically determine if an observed spatial pattern is better described by an extended source model (e.g., a spreading process) or a point-source model.

Methodology (as implemented in Fermipy software) [19]:

- Define Models: Fit two models to the data: a null model representing a point source, and an alternative model representing an extended source (e.g., a 2D Gaussian or Disk).

- Likelihood Scan: Perform a one-dimensional scan of the spatial extension parameter (e.g., width or radius of the source) over a predefined range.

- Calculate Test Statistic: For each value of the extension parameter, compute the log-likelihood of the data. The test statistic for spatial extension (( TS{ext} )) is derived from the difference in log-likelihoods between the best-fit extended model and the point-source model: ( TS{ext} = 2(\log L{ext} - \log L{ptsrc}) ) [19].

- Significance Testing: A large ( TS_{ext} ) value provides evidence against the point-source hypothesis, suggesting the process is spatially extended beyond a single point.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Spatial Validation on Model Performance Metrics

This table illustrates how using a naive random validation approach can severely overestimate model performance compared to a spatially robust method. The following data is synthesized from common findings in spatial literature [13] [16].

| Model Type | Study Area | Validation Method | Reported Accuracy (F1-Score) | Inference on Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Cover Classification | North Carolina, USA | Random Split | 0.92 | Overly Optimistic - Model performance is inflated due to spatial autocorrelation. |

| Land Cover Classification | North Carolina, USA | Spatial Block CV | 0.75 | Realistic - Better represents performance on truly new geographic areas. |

| Species Distribution Model | Amazon Basin | Random Split | 0.88 | Overly Optimistic - Fails to account for spatial heterogeneity in species-environment relationships. |

| Species Distribution Model | Amazon Basin | Spatial Cluster CV | 0.62 | Realistic - Highlights model's limitations when transferred across regions. |

Table 2: Guidelines for Selecting Geoimputation Methods for Missing Spatial Data

This table provides a structured approach to filling missing data based on the nature of the research question and data structure, following best practices [17].

| Research Context | Goal of Imputation | Recommended Fill Method | Recommended Neighborhood Definition | Rationale & Caution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health Risk Mapping (e.g., lead poisoning) | Avoid underestimation of risk | Maximum of neighbor values | Contiguous neighbors (share a border) | Overestimation is safer than underestimation for public safety. Assumes similar risk factors in adjacent areas. |

| Cartography / Visualization | Create an aesthetically complete map | Average of neighbor values | Fixed number of nearest neighbors | Smooths data and fills "holes." Less concerned with statistical bias. |

| Environmental Sensing (e.g., soil moisture) | Avoid influence of local outliers | Median of neighbor values | Neighbors within a fixed distance | Robust to sensor errors or extreme local values. Distance should reflect process scale. |

| Socio-economic Analysis | Preserve local distribution | Average of neighbor values | Spatial and attribute-based neighbors | If data is Missing Not At Random (MNAR), all methods can introduce significant bias. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Concept | Function in Spatial Analysis |

|---|---|

| Spatial Cross-Validation | A validation technique that partitions data by location to provide a realistic estimate of a model's performance when applied to new geographic areas [13]. |

| Replicability Map | A visualization tool that maps the geographic performance of a model, highlighting regions where it generalizes well and where it fails, thus quantifying spatial replicability [16]. |

| Geoimputation | The process of filling in missing data values in a spatial dataset using the values from neighboring features in space or time, guided by Tobler's First Law of Geography [17]. |

| Spatial Autocorrelation (SAC) | A measure of the degree to which data points near each other in space have similar values. It is a fundamental property of spatial data that must be accounted for to avoid biased models [13]. |

| Spatial Heterogeneity | The non-stationarity of underlying processes and relationships across a landscape. It is a primary reason why models trained in one area may not work in another [16] [13]. |

| Gravity / Radiation Models | Mathematical models used to describe and predict human movement patterns between locations (e.g., between census tracts), which are crucial for building accurate spatial epidemic models [18]. |

| Threshold Parameters (R₀) | In spatial models, the critical value for the basic reproductive number is often greater than 1 (e.g., 2.0-2.4 for lattice models), reflecting the constrained nature of local contacts [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Why does my spatial heterogeneity model fail to replicate when I change the spatial extent of the study area? A1: This is a common replicability challenge. The model's parameters might be over-fitted to the specific spatial scale of the initial experiment. To troubleshoot:

- Action: Re-run the core model on the original and new spatial extents, but only using a subset (e.g., 70%) of the data from each.

- Validation: Compare the model's performance on the withheld 30% of data for both extents. A significant performance drop on the new extent indicates over-fitting.

- Solution: Implement multi-scale spatial cross-validation to ensure model parameters are robust across different spatial scales [20].

Q2: How can I visually diagnose fitting errors in my spatial model's output?

A2: Use the Graphviz diagrams in the "Mandatory Visualization" section below. Compare your experimental workflow and results logic against the provided diagrams. Inconsistencies often reveal errors in data integration or result interpretation. The fixedsize attribute in Graphviz is crucial for preventing node overlap, which can misrepresent data relationships [21].

Q3: What is the most critical step in preparing single-cell RNA sequencing data for spatial heterogeneity analysis? A3: Ensuring batch effect correction and spatial normalization. Technical variations between sequencing batches can be misinterpreted as spatial heterogeneity.

- Protocol: Apply harmonization methods (e.g., Harmony, ComBat) before integrating data from multiple samples or regions. Validate by checking if known, ubiquitous cell markers show uniform expression across batches [20].

Q4: My Graphviz diagrams have poor readability. How can I improve the color contrast?

A4: Adhere to the WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) for enhanced contrast. For text within nodes, explicitly set the fontcolor to contrast highly with the fillcolor [22]. Use the provided color palette and the following principles:

- For Dark Text: Use light backgrounds (e.g.,

fillcolor="#FBBC05",fontcolor="#202124"). - For Light Text: Use dark backgrounds (e.g.,

fillcolor="#4285F4",fontcolor="#FFFFFF"). - Avoid combinations like

#F1F3F4(light gray) fill with#FFFFFF(white) text, which has insufficient contrast [22] [23].

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis

Diagram 2: Logic of Model Fit Replicability Challenges

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Spatial Heterogeneity Research |

|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Kits (e.g., 10x Genomics) | Enables profiling of gene expression at the individual cell level, fundamental for identifying cellular subpopulations within a tissue [20]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Slides (e.g., Visium) | Provides a grid-based system to capture and map gene expression data directly onto a tissue section, linking molecular data to spatial context. |

| Cell Type-Specific Antibodies | Used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or immunofluorescence (IF) to validate the presence and location of specific cell types identified by computational models. |

| Spatial Cross-Validation Software (e.g., custom R/Python scripts) | Computational tool for rigorously testing model performance across different spatial partitions of the data, crucial for assessing replicability [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Scale Spatial Cross-Validation

- Objective: To evaluate the robustness of a spatial heterogeneity model across varying spatial extents and prevent over-fitting.

- Methodology:

- Define a set of spatial extents (e.g., 1x1 mm, 2x2 mm, 5x5 mm) from your tissue sample.

- For each spatial extent, partition the data into k-folds (e.g., k=5). Ensure folds are spatially contiguous to avoid data leakage.

- Iteratively train the model on k-1 folds and validate on the held-out spatial fold.

- Repeat the process for all defined spatial extents.

- Quantitative Measures: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of the model's performance metric (e.g., R², AUC) across all folds and extents. A low standard deviation indicates high replicability [20].

Protocol 2: Validation of Spatial Clusters via IHC

- Objective: To biologically validate computationally derived spatial clusters of cell types.

- Methodology:

- Based on single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data, computationally identify regions (clusters) enriched with a specific cell type.

- Select tissue sections corresponding to these computationally identified regions.

- Perform immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining using a validated antibody for a marker gene highly expressed in that cell cluster.

- Quantify the density of marker-positive cells in the predicted regions versus control regions.

- Quantitative Measures: Use a statistical test (e.g., t-test) to compare cell density between the computationally predicted cluster and a randomly selected area of the same size. A p-value < 0.05 confirms the cluster's biological validity.

Methodological Frameworks for Defining and Applying Spatially Replicable Models

Knowledge-Based and Modeling-Goal-Driven Approaches for Intelligent Spatial Extent Determination

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I simply use my output Area of Interest (AOI) as the spatial extent for all my input data? Using the user-defined AOI for all inputs ignores that natural spatial processes extend beyond human-defined boundaries. For example, when extracting a stream network, the required Digital Elevation Model (DEM) must cover the entire upstream catchment area of the AOI; using only the AOI itself will ignore contributing upstream areas and produce incorrect or incomplete results due to the missing context of the spatial process [11].

FAQ 2: What is the core difference between execution-procedure-driven and modeling-goal-driven approaches?

- Execution-procedure-driven approaches require users to manually search for raw data and customize workflows based on the model's input requirements, relying heavily on user expertise and understanding of the complete modeling procedure [11].

- Modeling-goal-driven approaches automate the selection of suitable model input data and preparation methods, iteratively extending workflows starting from the user's modeling goal. This reduces reliance on the user's modeling expertise [11].

FAQ 3: What are the main types of knowledge used in modeling-goal-driven approaches for input preparation?

- Basic Input Data Descriptions: Formalizes basic data semantics (e.g., DEM, road networks) and data types (e.g., raster, polygon) to discover raw data and define input-output relationships [11].

- Application Context Knowledge: Incorporates knowledge about preparing proper input data based on specific application contexts, including factors like application purpose, study area characteristics, and data characteristics [11].

FAQ 4: How does improper spatial extent determination create problems in geographical model workflows? In workflows combining multiple models, an individual error in input data preparation can raise a chain effect, leading to cascading errors and ultimately incorrect final outputs. Each model often requires input data with different spatial extents due to distinct model and input characteristics [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Model Results Due to Incorrect Spatial Extents

Symptoms:

- Model outputs appear truncated or contain unexpected boundary artifacts.

- Results for flow accumulation, watershed delineation, or other process-based models are illogical or incomplete.

- Model performance degrades when applied to different geographical areas.

Solutions:

- Implement Knowledge Rules: Formalize and apply knowledge rules that systematically consider the semantic relation between spatial extents of input and output and the data type of the corresponding input [11].

- Adopt a Modeling-Goal-Driven Workflow: Use an approach that automatically determines the proper spatial extent for each input during the geographical model workflow building process, adapting to the user-assigned AOI [11].

- Validate with Known Cases: Test your workflow in an area where the correct spatial extent and expected output are known to verify the automatic determination logic.

Problem: Chain Effects and Cascading Errors in Multi-Model Workflows

Symptoms:

- Small errors in early model stages amplify in subsequent models.

- Difficulty isolating the source of inaccuracy in a complex workflow.

- Inconsistent outputs when re-running workflows with slightly different AOIs.

Solutions:

- Intelligent Spatial Extent Propagation: For each iterative step in the heuristic modeling process, automatically determine the spatial extent for the input of the current data preparation model. This ensures each step in the chain receives correctly bounded data [11].

- Workflow Automation: Utilize a prototype system (like the Easy Geo-Computation system) that integrates this intelligent approach, deriving an execution-ready workflow with minimal execution redundancy [11].

Problem: Handling Arbitrarily-Shaped or Complex Areas of Interest

Symptoms:

- Models developed for simple, rectangular AOIs fail when applied to complex, irregular shapes.

- Uncertainty in how model-specific spatial requirements (e.g., upstream area, interpolation neighborhood) interact with a complex AOI.

Solutions:

- Case-Specific Analysis: A case study on digital soil mapping for an arbitrary-shaped AOI validated that the intelligent approach effectively determines proper spatial extents for complex shapes [11].

- Leverage Advanced Geoprocessing: The approach combines knowledge rules with advanced geoprocessing functions within a cloud-native architecture to handle arbitrary AOIs [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Case Study for Validating Intelligent Spatial Extent Determination

Aim: To validate the effectiveness of the intelligent spatial extent determination approach for a Digital Soil Mapping (DSM) workflow within an arbitrarily defined rectangular AOI in Xuancheng, Anhui Province, China [11].

Methodology:

- Define Workflow: Establish a DSM workflow to predict Soil Organic Matter (SOM) content. This requires multiple environmental covariates (e.g., distance-to-river, meteorological data) derived from different source data (e.g., DEM, observatory stations) [11].

- Apply Knowledge Rules: Implement pre-defined knowledge rules to determine the correct spatial extent for each input:

- Compare Results: Execute the workflow using both the naive approach (using only the AOI extent for all inputs) and the intelligent approach (using automatically determined, correct extents).

- Validate Accuracy: Compare the outputs against ground-truthed soil data to assess the improvement in result accuracy and completeness.

Quantitative Validation Data

The table below summarizes key improvements offered by the intelligent approach, as demonstrated in the case study [11].

Table 1: Impact of Intelligent Spatial Extent Determination on Workflow Accuracy

| Aspect | Naive Approach (AOI as Input Extent) | Intelligent Spatial Extent Approach |

|---|---|---|

| DEM Extent for Hydrology | Limited to AOI boundary | Expanded to full upstream watershed |

| Spatial Interpolation Input | Limited to stations inside AOI | Includes stations near (outside) AOI |

| Output Stream Network | Incorrect/Incomplete (missing upstream contributors) | Hydrologically correct and complete |

| Final Model Output (SOM) | Spatially biased and inaccurate | Accurate and complete for the AOI |

| Workflow Robustness | Prone to chain-effect errors | Resilient; derived execution-ready workflow |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for Implementing Intelligent Spatial Extent Determination

| Item | Function in the Workflow | Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Rule Base | Encodes the systematic knowledge on how a model's input spatial extent relates to its output extent and data type. | Core intelligence component; requires expert knowledge formalization [11]. |

| Heuristic Modeling Engine | Executes the modeling-goal-driven workflow, iteratively selecting models and preparing inputs using the knowledge rules. | Drives the automated workflow building process [11]. |

| Advanced Geoprocessing Tools | Performs the spatial operations (e.g., watershed delineation, buffer creation, interpolation) to generate the correctly bounded input data. | Microservices like those in the EGC system prototype (e.g., catchment area calculation) [11]. |

| Prototype System (e.g., EGC) | An integrated browser/server-based geographical modeling system that provides the platform for deploying and running the intelligent workflow. | Cloud-native architecture with Docker containerization allows for seamless scaling [11]. |

| Spatial Indexes (R-trees, Quad-trees) | Data structures used within geoprocessing tools to efficiently determine topological relationships (e.g., adjacency, containment) between spatial objects [24]. | Enables fast processing of spatial queries necessary for extent calculations. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Conceptual Framework for Spatial Extent Determination

Conceptual Framework for Spatial Extent Determination

Diagram 2: Detailed Troubleshooting Logic for Spatial Workflows

Troubleshooting Logic for Spatial Workflows

The quantification of spatial extent represents a significant advancement in the analysis of Tau-PET neuroimaging, moving beyond traditional dichotomous assessments to provide a more nuanced understanding of disease progression. The TAU-SPEX (Tau Spatial Extent) metric has emerged as a novel approach that aligns with visual interpretation frameworks while capturing valuable interindividual variability in tau pathology distribution. This methodology addresses critical limitations of standard quantification techniques by providing a more intuitive, spatially unconstrained measure of tau burden that demonstrates strong associations with neurofibrillary tangle pathology and cognitive decline [25] [26] [27].

Within the broader context of model fit spatial extent replicability challenges, TAU-SPEX offers valuable insights into overcoming barriers related to spatial heterogeneity, measurement standardization, and result interpretation. This technical support document provides comprehensive guidance for researchers and drug development professionals implementing spatial extent quantification in their neuroimaging workflows, with specific troubleshooting advice for addressing common experimental challenges.

Key Concepts and Terminology

Understanding Spatial Extent in Neuroimaging

Spatial extent in neuroimaging refers to the proportional volume or area exhibiting pathological signal beyond a defined threshold. Unlike intensity-based measures that average signal across predefined regions, spatial extent quantification captures the topographic distribution of pathology throughout the brain [26] [27]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding disease progression patterns in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease, where the spatial propagation of tau pathology follows predictable trajectories that correlate with clinical symptoms.

The TAU-SPEX metric specifically quantifies the percentage of gray matter voxels with suprathreshold Tau-PET uptake using a threshold identical to that employed in visual reading protocols. This alignment with established visual interpretation frameworks facilitates clinical translation while providing continuous quantitative data for research and therapeutic development [25] [28].

The Replicability Challenge in Spatial Analysis

Spatial replicability refers to the consistency of research findings across different spatial contexts or locations. In geospatial AI and neuroimaging, this represents a significant challenge due to inherent spatial heterogeneity and autocorrelation in the data [16]. The concept of a "replicability map" has been proposed to quantify how location impacts the reproducibility and replicability of analytical models, emphasizing the need to account for spatial variability when interpreting results [16].

In Tau-PET imaging, replicability challenges manifest in multiple dimensions:

- Spatial heterogeneity: Tau pathology distribution varies significantly between individuals despite similar clinical presentations [26] [27]

- Methodological variability: Differences in preprocessing, thresholding, and regional definition can impact spatial extent measurements [26]

- Population differences: Cohort characteristics including disease stage, age, and genetic factors influence spatial patterns [29]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TAU-SPEX Calculation Workflow

The TAU-SPEX methodology was developed using [18F]flortaucipir PET data from 1,645 participants across four cohorts (Amsterdam Dementia Cohort, BioFINDER-1, Eli Lilly studies, and Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative) [26] [27]. The protocol involves these critical steps:

PET Acquisition: All participants underwent Tau-PET using [18F]flortaucipir radiotracer with target acquisition during the 80-100 minute post-injection interval. Data were locally attenuation corrected and reconstructed into 4 × 5-minute frames according to scanner-specific protocols [26] [27].

Visual Reading: Tau-PET images were visually assessed according to FDA and EMA approved guidelines without knowledge of TAU-SPEX or SUVr values. Visual read was performed on 80-100 min non-intensity-normalized images for some cohorts and on SUVr images for others [26] [27].

Image Processing: A region-of-interest was manually delineated around the cerebellum gray matter for reference region extraction. Images were intensity-normalized to the cerebellum to generate SUVr maps [26].

Threshold Application: A standardized threshold identical to that used for visual reading was applied to binarize voxels as tau-positive or tau-negative [25] [26].

Spatial Extent Calculation: TAU-SPEX was computed as the percentage of gray matter voxels with suprathreshold Tau-PET uptake in a spatially unconstrained whole-brain mask [25] [28].

Figure 1: TAU-SPEX Calculation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps for calculating the TAU-SPEX metric from raw PET data to final quantitative output.

Comparative Analysis Protocol

To validate TAU-SPEX against established methodologies, researchers performed comprehensive comparisons with traditional SUVr measures:

Whole-brain SUVr Calculation: Computed Tau-PET SUVr in a spatially unconstrained whole-brain region of interest.

Temporal Meta-ROI SUVr Calculation: Derived SUVr values from the commonly used temporal meta-ROI to align with established tau quantification methods [26] [27].

Performance Validation: Tested classification performance for distinguishing tau-negative from tau-positive participants, concordance with neurofibrillary tangle pathology at autopsy (n=18), and associations with concurrent and longitudinal cognition [25] [26].

Statistical Comparison: Compared receiver operating characteristic curves, accuracy metrics, and effect sizes between TAU-SPEX and SUVr measures across all analyses [25] [27].

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

TAU-SPEX has demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional SUVr measures across multiple validation frameworks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics established through validation studies:

Table 1: TAU-SPEX Performance Metrics Compared to Traditional SUVr Measures

| Performance Metric | TAU-SPEX | Whole-Brain SUVr | Temporal Meta-ROI SUVr |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC for Visual Read Classification | 0.97 | Lower than TAU-SPEX (p<0.001) | Lower than TAU-SPEX (p<0.001) |

| Sensitivity for Braak-V/VI Pathology | 87.5% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Specificity for Braak-V/VI Pathology | 100.0% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Association with Concurrent Cognition (β) | -0.36 [-0.29, -0.43] | Weaker association | Weaker association |

| Association with Longitudinal Cognition (β) | -0.19 [-0.15, -0.22] | Weaker association | Weaker association |

| Accuracy for Tau-Positive Identification | >0.90 | Lower accuracy | Lower accuracy |

| Positive Predictive Value | >0.90 | Lower PPV | Lower PPV |

| Negative Predictive Value | >0.90 | Lower NPV | Lower NPV |

Association with Pathological and Clinical Outcomes

Beyond technical performance, TAU-SPEX shows strong associations with clinically relevant outcomes:

Table 2: TAU-SPEX Associations with Pathological and Clinical Outcomes

| Outcome Measure | TAU-SPEX Association | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| NFT Braak-V/VI Pathology at Autopsy | High sensitivity (87.5%) and specificity (100%) | Strong pathological validation for identifying advanced tau pathology |

| Concurrent Global Cognition | β = -0.36 [-0.29, -0.43], p < 0.001 | Moderate association with current cognitive status |

| Longitudinal Cognitive Decline | β = -0.19 [-0.15, -0.22], p < 0.001 | Predictive of future cognitive deterioration |

| Tau-PET Visual Read Status | AUC: 0.97 for distinguishing tau-negative from tau-positive | Excellent concordance with clinical standard |

| Spatial Distribution Patterns | Captures heterogeneity among visually tau-positive cases | Provides information beyond dichotomous classification |

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust spatial extent quantification requires specific methodological components and analytical tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in the TAU-SPEX framework:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Components for Spatial Extent Quantification

| Reagent/Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| [18F]flortaucipir radiotracer | Binds to tau neurofibrillary tangles for PET visualization | FDA and EMA approved for clinical visual reading; used with 80-100 min acquisition protocol |

| Cerebellum Gray Matter Reference Region | Reference region for intensity normalization | Manually delineated ROI; used for generating SUVr maps and threshold determination |

| Whole-Brain Gray Matter Mask | Spatially unconstrained mask for voxel inclusion | Enables calculation without a priori regional constraints |

| Visual Reading Threshold | Binarization threshold for tau-positive voxels | Identical threshold used for clinical visual reading; ensures alignment with clinical standard |

| Spatial Frequency Maps | Visualization of spatial patterns across populations | Generated using BrainNet with "Jet" colorscale; shows voxel-wise percentage of suprathreshold participants |

| Automated Spatial Extent Pipeline | Calculation of TAU-SPEX metric | Custom pipeline calculating percentage of suprathreshold gray matter voxels |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Implementation Challenges

Challenge: Inconsistent Threshold Application Problem: Variable spatial extent measurements due to inconsistent threshold application across scans or researchers. Solution:

- Implement automated thresholding aligned with visual reading standards

- Establish quality control procedures with expert review of threshold application

- Use standardized reference region delineation protocols [26] [27]

Challenge: High Variance in Low Pathology Cases Problem: Elevated spatial extent measures in amyloid-negative cognitively unimpaired participants, potentially reflecting off-target binding. Solution:

- Combine spatial extent with intensity measures to distinguish specific from non-specific binding

- Establish cohort-specific reference ranges for different populations

- Implement quantitative filters for excluding likely off-target regions [26] [27]

Challenge: Spatial Heterogeneity Affecting Replicability Problem: Inconsistent findings across studies due to spatial heterogeneity in tau distribution patterns. Solution:

- Develop replicability maps to quantify spatial generalizability

- Implement spatial autocorrelation analysis in validation frameworks

- Use multi-cohort designs to account for population-specific spatial patterns [16]

Data Quality and Processing Issues

Challenge: Incomplete Brain Coverage Problem: Missing data in certain brain regions affecting spatial extent calculations. Solution:

- Implement quality checks for complete Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space coverage

- Develop protocols for handling truncation artifacts

- Establish exclusion criteria for scans with significant coverage gaps [26]

Challenge: Inter-scanner Variability Problem: Differences in PET scanner characteristics affecting quantitative values. Solution:

- Implement scanner-specific normalization procedures

- Use phantom scans to calibrate across devices

- Include scanner as a covariate in statistical models [26] [27]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How does TAU-SPEX address limitations of traditional SUVr measures? A: TAU-SPEX overcomes several key SUVr limitations: (1) it is not constrained to predefined regions of interest, capturing pathology throughout the brain; (2) it utilizes binary voxel classification, reducing sensitivity to subthreshold noise; (3) it provides more intuitive interpretation with a well-defined 0-100% range; and (4) it better captures heterogeneity among visually tau-positive cases where focal high-intensity uptake may yield similar SUVr values as widespread moderate-intensity uptake [26] [27].

Q: What are the computational requirements for implementing TAU-SPEX? A: The TAU-SPEX methodology requires standard neuroimaging processing capabilities including: (1) PET image normalization and registration tools; (2) whole-brain gray matter segmentation; (3) voxel-wise thresholding algorithms; and (4) basic volumetric calculation capabilities. The method can be implemented within existing PET processing pipelines without specialized hardware requirements [26] [27].

Q: How does TAU-SPEX perform across different disease stages? A: TAU-SPEX demonstrates strong performance across the disease spectrum. It effectively distinguishes tau-negative from tau-positive cases (AUC: 0.97) while also capturing variance among visually positive cases that correlates with cognitive performance. The metric shows moderate associations with both concurrent (β=-0.36) and longitudinal (β=-0.19) cognition, suggesting utility across disease stages [25] [26].

Q: What steps ensure replicability of spatial extent findings? A: Ensuring replicability requires: (1) standardized threshold application aligned with visual reading; (2) multi-cohort validation to account for population differences; (3) clear documentation of preprocessing and analysis parameters; (4) accounting for spatial autocorrelation in statistical models; and (5) generation of replicability maps to quantify spatial generalizability [26] [16].

Q: How can spatial extent measures be integrated into clinical trials? A: Spatial extent quantification can enhance clinical trials by: (1) providing continuous outcome measures beyond dichotomous classification; (2) detecting subtle treatment effects on disease propagation; (3) offering more intuitive interpretation for clinical audiences; and (4) capturing treatment effects on disease topography that might be missed by regional SUVr measures. A recent survey found 63.5% of experts believe quantitative metrics should be combined with visual reads in trials [26] [27].

Advanced Spatial Replicability Framework

The implementation of spatial extent quantification must address fundamental replicability challenges inherent in spatial data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the key considerations for ensuring robust and replicable spatial extent measurements:

Figure 2: Spatial Replicability Framework - This diagram illustrates the major challenges in spatial replicability (red) and corresponding methodological solutions (green) for robust spatial extent measurements.

Implementing Replicability Maps

Replicability maps represent a novel approach to quantifying the spatial generalizability of findings. These maps incorporate spatial autocorrelation and heterogeneity to visualize regions where results are most likely to replicate across different populations or studies [16]. Implementation involves:

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis: Quantifying how similarity in tau pathology varies with spatial proximity

- Cross-Validation Framework: Implementing spatial cross-validation that accounts for geographic structure

- Uncertainty Quantification: Mapping regional confidence intervals for spatial extent measures

- Generalizability Index: Developing quantitative scores for spatial replicability across brain regions

This approach directly addresses the "replicability crisis" in spatial analysis by explicitly acknowledging and modeling spatial heterogeneity rather than assuming uniform effects throughout the brain [16] [2].

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for Spatial Pattern Detection and Prediction

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Spatial AI Experiments

My model performs well on synthetic data but fails on real-world data. Why?

This is a classic problem of model generalization. A model trained on synthetic examples is only useful if it can effectively transfer to real-world test cases. This challenge is particularly pronounced in high-dimensional phase transitions, where dynamics are more complex than in simple bifurcation transitions [31].

- Root Cause: The synthetic data likely lacks the full complexity, noise, and heterogeneity of real-world spatial data. Your model may have overfitted to the idealized patterns of the training data.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Compare key statistical properties (e.g., spatial autocorrelation, point distribution) between your synthetic and real-world datasets.

- Use a small, held-out set of real-world data for validation during training to monitor generalization performance.

- Solution:

- Data Augmentation: Introduce realistic noise, transformations, and variations into your synthetic training data.

- Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a broader set of spatial data, then fine-tune it on your specific synthetic dataset. This can help the model learn more generalizable features.

- Domain Adaptation: Employ techniques that explicitly minimize the discrepancy between the feature distributions of your synthetic (source) and real-world (target) data.

How can I diagnose overfitting or underfitting in my spatial model?

Evaluating model performance correctly is essential before diving into the root cause [32].

- Symptoms of Overfitting: High accuracy on training data but poor performance on validation/test data. The model learns the noise and specific details of the training set instead of the underlying spatial patterns.

- Symptoms of Underfitting: Poor performance on both training and validation data, indicating the model is too simple to capture the relevant spatial relationships.

| Metric | Overfitting Indicator | Underfitting Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Loss Function | Training loss << validation loss | Training loss ≈ validation loss, both high |

| Accuracy/Precision | Training >> validation | Both low |

| Feature Importance | High importance on nonsensical features | No clear important features identified |

- Fixes for Overfitting:

- Increase training data or use data augmentation.

- Apply stronger regularization (e.g., L1/L2, Dropout).

- Reduce model complexity (e.g., fewer layers/nodes in a neural network).

- For Random Forests, reduce

max_depthor increasemin_samples_leaf.

- Fixes for Underfitting:

My model's predictions lack spatial coherence. How can I improve them?

Standard models sometimes fail to capture the intrinsic spatial relationships in the data.

- Root Cause: The model architecture or algorithm may not be designed to account for spatial context and neighborhood dependencies.

- Solution:

- Choose spatially-aware algorithms: Algorithms like Random Forest can inherently assess complex, non-linear feature relationships, making them versatile for spatial data. K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN) uses proximity to classify or predict values for spatial data points [33].

- Incorporate spatial features: Explicitly include spatial covariates like coordinates, distance to key features, or spatial lag variables in your model.

- Use advanced architectures: For more complex tasks, consider Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Networks, which are state-of-the-art for analyzing dynamic spatial-temporal patterns by learning from spatial relationships [33]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can also learn spatial hierarchies from raster data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the top machine learning algorithms for spatial pattern detection in 2025?

The choice of algorithm should be guided by your project objectives, data complexity, and required interpretability [33]. The following algorithms are recognized for their versatility and efficiency with complex geospatial datasets [33].

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Ideal Spatial Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Robust to noise & outliers; Handles non-linear relationships; Provides feature importance [33]. | Land cover classification; Environmental monitoring; Soil and crop analysis [33]. |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN) | Simple to implement and interpret; No training phase; Versatile for classification & regression [33]. | Land use classification; Urban planning (finding similar areas); Environmental parameter prediction [33]. |

| Gaussian Processes | Provides uncertainty quantification; Models complex, non-linear relationships [33]. | Spatial interpolation; Resource estimation; Environmental forecasting. |

| Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Networks | Captures dynamic spatial-temporal patterns; State-of-the-art for complex relational data [33]. | Traffic flow forecasting; Climate anomaly detection; Urban growth modeling [33]. |

How can I ensure my spatial AI model is reproducible?

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of scientific research, especially when addressing model fit spatial extent replicability challenges.

- Document Everything: Meticulously document data preprocessing steps, model architectures, hyperparameters, and random seeds used.

- Version Control: Use version control systems (like Git) for both your code and datasets.

- Adhere to FAIR Principles: Ensure your data and models are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. This framework is central to initiatives like the Spatial AI Challenge and ensures your work is a valuable resource for the community [34].

- Use Computationally Reproducible Environments: Package your analysis in reproducible containers (e.g., Docker) or use platforms that support executable research compendiums, like Jupyter notebooks, which are used in competitions like the Spatial AI Challenge [34].

What should I do if my model fails to detect subtle, "hidden" patterns in point cloud data?

This is a problem of high-dimensional pattern recognition. Point clouds contain millions of data points with multiple attributes (X, Y, Z, intensity, etc.), creating a complex matrix beyond human visual perception [35].

- Leverage Advanced Deep Learning: Use architectures designed for point clouds (e.g., PointNet++, Dynamic Graph CNNs) that process data hierarchically. These models build understanding from local geometric features (e.g., surface normals, curvature) up to scene-level semantic relationships, detecting subtle statistical signatures of issues like material degradation or early plant disease [35].

- Focus on Feature Engineering: Instead of raw points, calculate derived mathematical properties such as:

- Standard deviation of point heights within a local area (roughness).

- Local planarity coefficients.

- Variations in surface normal vectors.

- Spatial autocorrelation patterns.

- Incorporate Contextual Rules: Train your model to understand spatial relationships (e.g., power lines maintain consistent elevation over terrain). Anomalies that violate these learned rules are often the subtle patterns of interest [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential "reagents" – algorithms, data principles, and tools – for a spatial AI research lab.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Random Forest Algorithm | A versatile "workhorse" for both classification and regression on spatial data, robust to noise and capable of identifying important spatial features [33]. |

| Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Network | The state-of-the-art "specialist" for modeling dynamic processes that evolve over space and time, such as traffic or disease spread [33]. |

| FAIR Data Principles | The "protocol" for ensuring your spatial data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, which is critical for replicable research [34]. |

| I-GUIDE Platform | An advanced "cyber-infrastructure" that provides the computational environment and tools for developing and testing reproducible spatial AI models [34]. |