Statistical Validation of Brain Signatures: A Multi-Cohort Framework for Robust Biomarker Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the statistical validation of brain signatures across multiple cohorts.

Statistical Validation of Brain Signatures: A Multi-Cohort Framework for Robust Biomarker Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the statistical validation of brain signatures across multiple cohorts. It explores the foundational shift from theory-driven to data-driven brain mapping, detailing rigorous methodologies for developing and optimizing signatures in discovery datasets. The content addresses critical challenges like dataset size and heterogeneity, offering troubleshooting strategies. A core focus is the multi-cohort validation framework, demonstrating how to establish model fit and spatial replicability while benchmarking performance against traditional models. Synthesizing key takeaways, the article concludes with future directions for translating validated brain signatures into clinically useful tools for personalized medicine and CNS drug development.

From Brain Mapping to Predictive Models: The Theoretical Shift to Data-Driven Signatures

The concept of a "brain signature of cognition" represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, moving from theory-driven hypotheses to a data-driven, exploratory approach for identifying key brain regions involved in specific cognitive functions [1]. This evolution has been fueled by the availability of large-scale neuroimaging datasets and increased computational power, enabling researchers to discover "statistical regions of interest" (sROIs or statROIs) that maximally account for brain substrates of behavioral outcomes [1]. Unlike traditional lesion-driven approaches that might miss subtler effects, the signature approach aims to provide a more complete accounting of brain-behavior associations by selecting features in a data-driven manner, often at a fine-grained voxel level without relying on predefined ROI boundaries [1]. The validation of these signatures across multiple cohorts is essential for establishing robust brain phenotypes that can reliably model substrates of behavioral domains, with recent research demonstrating that signatures developed through rigorous statistical validation outperform theory-based models in explanatory power [1] [2].

Methodological Comparison: From ROIs to Multivariate Predictive Models

Traditional Theory-Driven and Lesion-Driven Approaches

Traditional approaches to understanding brain-behavior relationships have primarily been theory-driven or based on lesion studies. These methods have yielded valuable insights but possess inherent limitations. Theory-driven approaches rely on pre-existing hypotheses about which brain regions should be involved in specific functions, potentially missing subtle yet significant effects outside expected regions [1]. Similarly, lesion-based methods identify crucial regions for cognitive functions by studying deficits in patients with brain damage but may overlook the distributed network nature of brain organization [3]. Both approaches typically use predefined anatomical atlas regions of interest (ROIs), which assume functional boundaries align with anatomical boundaries—an assumption that may not always hold true [1]. This constraint means combinations of atlas ROIs cannot optimally fit an outcome of interest when brain-behavior associations cross ROI boundaries [1].

Modern Data-Driven Signature Approaches

Modern signature approaches represent a significant methodological advancement by leveraging data-driven feature selection to identify brain regions most associated with behavioral outcomes [1]. These methods can be implemented at various levels of analysis:

- Voxel-based regressions directly compute associations at the voxel level without predefined ROIs [1]

- Machine learning algorithms including support vector machines, support vector classification, relevant vector regression, and convolutional neural nets enable exploratory feature selection [1]

- Multivariate lesion-behavior mapping (LBM) identifies causal relationships between damage patterns and behavior [3]

A key advantage of signature approaches is their ability to capture distributed patterns that cross traditional anatomical boundaries, potentially providing more complete accounts of brain-behavior relationships [1]. However, challenges remain in interpretability, particularly with complex machine learning models that can function as "black boxes" [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Methodological Approaches to Brain-Behavior Mapping

| Feature | Theory-Driven/ROI-Based | Lesion-Behavior Mapping | Brain Signature Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Basis | Pre-existing hypotheses & anatomical atlases | Natural experiments from brain damage | Data-driven exploratory analysis |

| Feature Selection | A priori region definition | Voxel-wise or multivariate damage mapping | Statistical association with behavior |

| Key Strength | Straightforward interpretation | Established causal inference | Comprehensive feature selection |

| Key Limitation | May miss important effects | Limited to available lesion patterns | Requires large samples for validation |

| Validation Needs | Conceptual coherence | Replication across lesion types | Multi-cohort reproducibility |

Predictive Validity Comparison (PVC) Framework

The Predictive Validity Comparison (PVC) method represents a significant advancement for comparing lesion-behavior maps by establishing statistical criteria for determining whether two behaviors require distinct neural substrates [3]. This framework addresses limitations of traditional comparison methods:

- Overlap Method: Creates intersection and subtraction maps but doesn't account for nuisance variance or provide statistical criteria for "distinctness" [3]

- Correlation Method: Determines if LBMs are significantly correlated but cannot establish they are identical [3]

The PVC method tests whether individual differences across two behaviors result from single versus distinct lesion patterns by comparing predictive accuracy under null (single pattern) and alternative (distinct patterns) hypotheses [3]. This provides a principled approach to establishing when behaviors arise from the same versus different brain regions.

Experimental Protocols for Signature Validation

Multi-Cohort Validation Framework

Robust validation of brain signatures requires rigorous testing across multiple independent cohorts to establish both model fit replicability and spatial consistency [1]. The protocol implemented by Fletcher et al. (2023) demonstrates this comprehensive approach:

Discovery Phase:

- Utilize large discovery cohorts (578 participants from UC Davis ADRC and 831 from ADNI 3)

- Compute regional gray matter thickness associations with behavioral outcomes

- Generate 40 randomly selected discovery subsets of size 400 in each cohort

- Create spatial overlap frequency maps and define high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1]

Validation Phase:

- Use separate validation datasets (348 participants from UCD and 435 from ADNI 1)

- Evaluate replicability of cohort-based consensus model fits in 50 random subsets of each validation cohort

- Compare explanatory power of signature models against competing theory-based models [1]

This approach addresses the critical need for large sample sizes, as recent research indicates replicability depends on discovery in datasets numbering in the thousands [1]. The method also accounts for cohort heterogeneity, ensuring the full range of variability in brain pathology and cognitive function is represented.

Consensus Signature Derivation

The derivation of consensus signatures through spatial frequency mapping represents a significant methodological advancement for ensuring robustness:

Performance Metrics and Statistical Validation

The validation of brain signatures requires multiple complementary assessment strategies:

- Spatial Replication: Assess convergent consensus signature regions across independent cohorts [1]

- Model Fit Correlations: Evaluate replicability through correlation of signature model fits across multiple validation subsets [1]

- Explanatory Power Comparison: Compare signature model performance against theory-based models in full cohort analyses [1]

- Predictive Accuracy: For PVC framework, compare quality of predictions under null and alternative hypotheses [3]

Table 2: Multi-Cohort Validation Results for Brain Signatures

| Validation Metric | UCD Discovery → ADNI Validation | ADNI Discovery → UCD Validation | Theory-Based Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Convergence | Convergent consensus regions identified | Convergent consensus regions identified | Dependent on a priori regions |

| Model Fit Correlation | High correlation across 50 validation subsets | High correlation across 50 validation subsets | Variable across cohorts |

| Explanatory Power | Outperformed competing models | Outperformed competing models | Consistently lower than signatures |

| Cross-Domain Comparison | Strongly shared substrates for neuropsychological and everyday memory | Strongly shared substrates for both memory domains | Limited cross-domain comparability |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Components for Brain Signature Research

| Research Component | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Neuroimaging Data | Provides structural and functional brain measures for signature development | T1-weighted MRI for gray matter thickness; task-based or resting-state fMRI [1] |

| Cognitive Assessment Tools | Measures behavioral outcomes of interest | Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales (SENAS); Everyday Cognition scales (ECog) [1] |

| Statistical Processing Pipelines | Image processing and feature extraction | Brain extraction via convolutional neural nets; affine and B-spline registration; tissue segmentation [1] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Multivariate pattern analysis and feature selection | Support vector machines; relevant vector regression; deep learning with convolutional neural nets [1] |

| Validation Cohorts | Independent samples for testing signature robustness | Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI); UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Research Center cohort [1] |

| Predictive Validity Comparison | Determines whether behaviors share neural substrates | PVC web app for comparing lesion-behavior maps [3] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Explanatory Power Across Methodologies

Direct comparisons between brain signature approaches and traditional methods demonstrate the superior performance of data-driven methods:

- Signature models consistently outperformed theory-based models in explanatory power when validated across full cohorts [1]

- Consensus signature model fits were highly correlated across multiple validation subsets, indicating high replicability [1]

- Spatial replication produced convergent consensus signature regions across independent cohorts [1]

The predictive validity comparison framework has shown high sensitivity and specificity in simulation studies, accurately detecting when behaviors were mediated by different regions versus the same region [3]. In contrast, both overlap and correlation methods performed poorly on simulated data with known ground truth [3].

Application Across Behavioral Domains

The flexibility of signature approaches is evident in their successful application to multiple behavioral domains:

- Episodic memory signatures derived from neuropsychological assessments [1]

- Everyday memory function measured by informant-based ECog scales [1]

- Feature and spatial attention with distinct yet shared neural signatures [4]

Comparative analyses across domains reveal strongly shared brain substrates for related cognitive functions, suggesting signature approaches can discern both common and unique neural patterns across behavioral domains [1].

Robustness to Methodological Variations

The performance of signature methods depends critically on several methodological factors:

- Discovery set size: Samples in the thousands often needed for replicability [1]

- Cohort heterogeneity: Representation of full variability in brain pathology and cognitive function enhances generalizability [1]

- Feature selection method: Voxel-level approaches may capture distributed patterns better than ROI-based methods [1]

Well-validated signature models demonstrate reduced in-discovery-set versus out-of-set performance bias compared to earlier implementations, particularly when using multiple discovery set generation and aggregation techniques [1].

The field of cognitive neuroscience is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from analyzing isolated brain regions to modeling information processing that is distributed across interconnected neural systems. This transition represents a fundamental change in how we conceptualize brain function—from a collection of specialized modules to an integrated network where mental events emerge from complex, system-wide interactions [5]. Where traditional brain mapping treated local responses as outcomes to be explained, the new approach uses brain measurements to predict mental processes and behavior, reversing this equation to create truly predictive models of brain function [5].

This shift is driven by growing recognition that the brain employs population coding strategies, where information is distributed across intermixed neurons rather than encoded in highly selective individual cells [5]. Neurophysiological studies have consistently demonstrated that even the most stimulus-predictive single neurons contain insufficient information to accurately predict behavior, whereas joint activity across neural populations provides robust, high-capacity representation [5]. This distributed architecture provides combinatorial coding benefits, allowing a finite number of neural elements to represent nearly infinite system states through their patterned activity [5].

Theoretical Foundations: From Modules to Networks

The Limitations of Localization

The traditional modular view of brain function has roots in philosophical assumptions about mental processes and early lesion studies that linked specific cortical areas to deficits in speech, perception, and action [5]. This perspective dominated early neuroimaging research, leading to analytical approaches that treated individual voxels as independent observation units. However, this framework suffers from significant theoretical and practical limitations in explaining how the brain actually represents complex information.

The modular view fails to account for the combinatorial flexibility of neural systems and their robustness to damage. More critically, it cannot explain how the brain represents similarities and associations across objects and concepts, or how it generalizes learning to novel situations [5]. These limitations become particularly apparent when studying higher-order cognitive functions like decision-making, emotion, and language, which clearly involve coordinated activity across multiple brain systems.

Principles of Distributed Representation

Distributed neural representation offers several adaptive advantages that may explain its evolution and prevalence throughout nervous systems:

- Robustness to noise and damage: Distributed codes are inherently redundant, allowing function to persist despite neuronal loss or signal corruption [5]

- Combinatorial capacity: By representing features as patterns across populations, neural systems can encode exponentially more information than with dedicated neurons [5]

- Similarity representation: Natural relationships between stimuli can be encoded through similar activity patterns, supporting generalization and associative learning [5]

- Multiplexing capability: The same neuronal population can represent multiple types of information through different activity patterns [5]

These principles find parallel in artificial neural networks, particularly deep learning models, where distributed representations in hidden layers have proven critical for advanced pattern recognition and prediction tasks [5].

Methodological Innovations: New Tools for System-Level Analysis

Advanced Recording Technologies

Cutting-edge neurotechnologies now enable unprecedented access to brain-wide activity patterns. The BRAIN Initiative has accelerated development of tools for large-scale neural monitoring, emphasizing the need to "produce a dynamic picture of the functioning brain by developing and applying improved methods for large-scale monitoring of neural activity" [6]. These technologies move beyond isolated recordings to capture distributed dynamics across entire neural circuits.

Recent studies demonstrate the power of these approaches. One brain-wide analysis of over 50,000 neurons in mice performing decision-making tasks revealed how movement-related signals are structured across and within brain areas, with systematic variations in encoding strength from sensory to motor regions [7]. Such massive-scale recordings provide the empirical foundation for building comprehensive distributed models.

Multivariate Analytical Frameworks

The theoretical shift to distributed representation requires corresponding advances in analytical methodology. Multivariate predictive models now dominate cutting-edge neuroscience research, with several distinctive approaches emerging:

Table 1: Multivariate Modeling Approaches in Neuroscience

| Approach | Core Methodology | Key Applications | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Signatures | Identifying reproducible neural patterns that predict mental states across individuals [5] | Pain, emotion, cognitive tasks [5] | Generalizability across subjects and studies |

| Whole-Brain Dynamics | Systematic comparison of interpretable features from neural time-series [8] | Neuropsychiatric disorders, resting-state dynamics [8] | Comprehensive feature space coverage |

| Multimodal Integration | Fusing video, audio, and linguistic representations to predict brain responses [9] | Naturalistic stimulus processing, cognitive encoding [9] | Ecological validity for complex, real-world processing |

| Machine Learning Markers | Quantifying disease impact through multivariate pattern analysis [10] | Cardiovascular/metabolic risk factors, aging [11] [10] | Individual-level severity quantification |

Implementing distributed brain models requires specialized methodological resources and analytical tools:

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Distributed Neural Modeling

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Datasets | Dallas Lifespan Brain Study (DLBS) [12], Algonauts Project [9] | Provide comprehensive multimodal data across lifespan and cognitive states | Model training and validation, longitudinal studies |

| Feature Analysis Libraries | hctsa [8], pyspi [8] | Compute diverse time-series features for systematic comparison | Quantifying intra-regional and inter-regional dynamics |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | SPARE models [10], Brain-machine Fusion Learning (BMFL) [13] | Derive individualized biomarkers from multivariate patterns | Disease classification, out-of-distribution generalization |

| Statistical Learning Models | Local transition probability models [14], hierarchical Bayesian inference [14] | Characterize sequence learning and statistical inference | Investigating temporal processing at multiple timescales |

Experimental Evidence: Validating Distributed Representations

Case Study: Large-Scale Neural Encoding of Movement

A compelling demonstration of distributed representation comes from a brain-wide analysis of movement encoding in mice [7]. This study employed three complementary approaches to relate neural activity to ongoing movements:

- Marker-based tracking using DeepLabCut to track specific body parts

- Embedding approaches using autoencoders to learn low-dimensional movement representations

- End-to-end learning directly predicting neural activity from video pixels

The results revealed a fine-grained structure of movement encoding across the brain, with systematic variations in how different areas represent motor information. Crucially, the study found that "movement-related signals differed across areas, with stronger movement signals close to the motor periphery and in motor-associated subregions" [7]. This demonstrates how distributed representations are systematically organized rather than randomly scattered throughout the brain.

Clinical Applications: Machine Learning for Disease Signatures

The distributed framework shows particular promise in clinical neuroscience, where traditional localized biomarkers often lack sensitivity and specificity. Recent work using machine learning to identify neuroanatomical signatures of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases demonstrates this power [10].

Researchers developed the SPARE-CVM framework to quantify spatial patterns of atrophy and white matter hyperintensities associated with five cardiovascular-metabolic conditions [10]. Using harmonized MRI data from 37,096 participants across 10 cohort studies, they generated individualized severity markers that:

- Outperformed conventional structural MRI markers with a ten-fold increase in effect sizes

- Captured subtle patterns at sub-clinical stages

- Were most sensitive in mid-life (45-64 years)

- Showed stronger associations with cognitive performance than diagnostic status alone [10]

This approach demonstrates how distributed patterns provide more sensitive and specific disease biomarkers than traditional localized measures.

Temporal Processing: Multiscale Sequence Learning

The distributed nature of neural computation extends to temporal processing, as revealed by research on sequence learning using magnetoencephalography (MEG) [14]. This work shows how successive brain waves reflect progressive extraction of sequence statistics at different timescales, with "early post-stimulus brain waves denoted a sensitivity to a simple statistic, the frequency of items estimated over a long timescale," while "mid-latency and late brain waves conformed qualitatively and quantitatively to the computational properties of a more complex inference: the learning of recent transition probabilities" [14].

This multiscale processing framework illustrates how distributed representations operate across temporal dimensions, with different brain systems specializing in different statistical regularities and timescales.

Validation Frameworks: Ensuring Reliability Across Cohorts

Statistical Validation of Brain Signatures

The shift to distributed models necessitates rigorous validation frameworks to ensure reliability and generalizability. Key considerations include:

- Cross-cohort validation: Testing models on independent datasets to avoid overfitting

- Demographic robustness: Ensuring performance across age, sex, and ancestral groups

- Clinical utility: Establishing meaningful relationships with behavioral and cognitive outcomes

The SPARE-CVM study exemplifies this approach, with external validation in 17,096 participants from the UK Biobank [10]. Similarly, the Brain Vision Graph Neural Network (BVGN) framework for brain age estimation was validated on 34,352 MRI scans from the UK Biobank after initial development on Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative data [11].

Handling Comorbidity and Complexity

Real-world clinical applications often involve patients with multiple co-occurring conditions, creating challenges for biomarker specificity. Distributed models show promise in addressing this complexity through multivariate pattern recognition. The SPARE-CVM approach demonstrated that "specific CVM signatures can be detected even in the presence of additional CVMs," with more than 30% of their sample having two or more co-occurring conditions [10].

Future Directions: The Next Frontier in Distributed Modeling

Brain-Machine Fusion Learning

An emerging frontier combines brain-inspired approaches with artificial intelligence through brain-machine fusion learning (BMFL). This framework "extracts the prior cognitive knowledge contains in the human brain through the brain transformer module, and fuses the prior cognitive knowledge with the computer vision features" to improve out-of-distribution generalization [13]. This approach acknowledges that while artificial neural networks were inspired by the brain, human cognitive systems still outperform artificial systems in robustness and generalization, particularly under challenging conditions.

Dynamic Network Neuroscience

Future research will increasingly focus on how distributed representations evolve over time and context. Systematic comparison of whole-brain dynamics offers promise for identifying "interpretable signatures of whole-brain dynamics" that capture both intra-regional activity and inter-regional coupling [8]. This approach has demonstrated that "combining intra-regional properties with inter-regional coupling generally improved performance, underscoring the distributed, multifaceted changes to fMRI dynamics in neuropsychiatric disorders" [8].

Clinical Translation and Personalized Medicine

The ultimate test of distributed models lies in their clinical utility. Promising applications include:

- Early risk detection through sensitive multivariate biomarkers [11] [10]

- Personalized intervention targeting based on individual pattern expression

- Treatment response monitoring through longitudinal pattern tracking

- Cognitive decline prediction in aging populations [12]

The brain age gap derived from BVGN, for instance, demonstrated "the highest discriminative capacity between cognitively normal and mild cognitive impairment than general cognitive assessments, brain volume features, and apolipoprotein E4 carriage" [11], highlighting the clinical potential of distributed frameworks.

The paradigm shift from localized effects to distributed brain models represents more than a methodological change—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize neural computation. By embracing the distributed nature of neural representation, researchers can develop more accurate, sensitive, and clinically useful models of brain function and dysfunction. The future of neuroscience lies in understanding how patterns of activity across distributed networks give rise to mental events, ultimately bridging the gap between brain activity and human experience.

Understanding how the brain encodes information requires bridging vastly different spatial and temporal scales. At the microscopic level, information is distributed across populations of neurons through complex patterns of individual cell activity, heterogeneous response properties, and precise spike timing [15]. Simultaneously, non-invasive neuroimaging techniques capture brain-wide activity patterns at a macroscopic level, creating what researchers term "brain signatures" of cognitive functions or disease states [1]. The fundamental challenge lies in establishing robust theoretical and statistical links between these levels of analysis—determining how population coding principles manifest in measurable neuroimaging signals, and how these signatures can be validated across diverse populations to ensure reliability [1].

This connection is not merely academic; it has profound implications for diagnosing neurological disorders and developing targeted therapies. The emerging consensus suggests that neural population codes are organized at multiple spatial scales, with microscopic and population dynamics interacting to create state-dependent processing [15]. This review synthesizes current theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, and validation paradigms that link population neural coding with neuroimaging signatures, with particular emphasis on statistical validation across multiple cohorts—a critical requirement for establishing biologically meaningful biomarkers.

Theoretical Foundations: From Neural Populations to Brain Networks

Key Principles of Neural Population Coding

Information processing in the brain relies on distributed patterns of activity across neural populations rather than individual neurons [15]. Several fundamental principles govern this population coding:

Heterogeneity and Diversity: Neurons within a population exhibit diverse stimulus selectivity, with different preference profiles and tuning widths that provide complementary information [15]. This heterogeneity increases the coding capacity of the population and enables more complex representations.

Temporal Dynamics: Informative response patterns include not just firing rates but also the relative timing between neurons at millisecond precision [15]. This temporal dimension carries information that cannot be extracted from rate-based codes alone.

Mixed Selectivity: In higher association areas, neurons often show complex, nonlinear selectivity to multiple task variables [15]. This mixed selectivity increases the dimensionality of population representations, enabling simpler linear readout by downstream areas.

Sparseness and Efficiency: Cortical activity is characterized by sparseness—at any moment, only a small fraction of neurons are highly active [15]. This sparse coding strategy may optimize metabolic efficiency and facilitate separation of synaptic inputs.

Noise Correlations: Correlations in trial-to-trial variability between neurons (noise correlations) significantly impact information transmission, especially in large populations [16]. These correlations can either enhance or limit information depending on their structure.

Neuroimaging Signatures as Macroscopic Manifestations

Neuroimaging signatures represent statistical patterns in brain imaging data that correlate with specific cognitive states, behaviors, or disease conditions [1]. Unlike theory-driven approaches that focus on predefined regions, signature-based methods identify brain-wide patterns through data-driven exploration:

Spatial Distribution: Signatures often recruit distributed networks that cross traditional anatomical boundaries, potentially reflecting the distributed nature of population coding [1].

Multivariate Nature: Unlike univariate approaches that consider regions in isolation, signatures capture distributed patterns of activity or structure, analogous to how information is distributed across neural populations [1].

State Dependence: Both neural population codes and neuroimaging signatures exhibit state dependence, varying with brain states, attention, and other slow variables that modulate neural responsiveness [15].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Neural Codes and Neuroimaging Signatures

| Property | Neural Population Coding | Neuroimaging Signatures |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Scale | Microscopic (individual neurons) | Macroscopic (brain regions/voxels) |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond precision | Seconds (fMRI) to milliseconds (EEG/MEG) |

| Dimensionality | High (thousands of neurons) | Lower (thousands of voxels) |

| Measurement Type | Direct electrical activity | Indirect hemodynamic/metabolic signals |

| Information Carrier | Spikes, local field potentials | BOLD signal, cortical thickness |

Methodological Frameworks: Statistical Validation Across Cohorts

Computational Models Linking Neural Activity to Imaging Signals

Computational models provide a crucial theoretical bridge between neural population activity and neuroimaging signals. The exponential family framework offers a powerful mathematical foundation for modeling population responses [16]. These models capture key response statistics while supporting accurate Bayesian decoding—essential for understanding how information is represented in neural populations.

Advanced modeling approaches include:

Poisson Mixture Models: These models effectively capture neural variability and covariability in large populations by mixing multiple independent Poisson distributions [16]. The resulting models can exhibit both over- and under-dispersed response variability, matching experimental observations.

Conway-Maxwell-Poisson Distributions: Extensions of standard Poisson models that capture a broader range of variability patterns observed in cortical recordings [16].

Latent Variable Models: Frameworks that jointly model behavioral choices and neural activity through shared latent variables representing cognitive processes like evidence accumulation [17].

Signature Validation Methodologies

Robust validation of neuroimaging signatures requires rigorous statistical approaches across multiple cohorts:

Consensus Mask Generation: Creating spatial overlap frequency maps from multiple discovery subsets and defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1]. This approach leverages random subsampling to identify robust features.

Cross-Cohort Replication: Testing signature performance in independent validation datasets to assess generalizability beyond the discovery cohort [1].

Model Fit Comparison: Comparing signature models against theory-based models to evaluate explanatory power and utility [1].

Table 2: Statistical Validation Metrics for Brain Signatures

| Validation Metric | Methodology | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Replicability | Convergence of signature regions across discovery subsets | High convergence indicates robust spatial pattern |

| Model Fit Replicability | Correlation of model fits across validation subsets | High correlation indicates reliable predictive power |

| Explanatory Power | Comparison with theory-based models using variance explained | Superior performance suggests comprehensive feature selection |

| Cross-Cohort Generalizability | Application to independent datasets from different sources | High generalizability indicates clinical utility |

The validation process must address the "in-discovery-set versus out-of-set performance bias" [1], where signatures typically perform better on the data they were derived from compared to external datasets. Recent approaches mitigate this through aggregation across multiple discovery sets [1].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in Multiple Domains

Evidence Accumulation Across Brain Regions

Research on evidence accumulation provides compelling examples of how population coding principles manifest across different brain regions. A unified framework modeling stimulus-driven behavior and multi-neuron activity simultaneously revealed distinct accumulation strategies across rat brain regions [17]:

Frontal Orienting Fields (FOF): Exhibited dynamic instability, favoring early evidence with neural responses resembling categorical choice representations [17].

Anterodorsal Striatum (ADS): Reflected near-perfect accumulation, representing evidence in a graded manner with high fidelity [17].

Posterior Parietal Cortex (PPC): Showed weaker correlates of graded evidence accumulation compared to ADS [17].

Crucially, each region implemented a distinct accumulation model, all of which differed from the model that best described the animal's overall choices [17]. This suggests that whole-organism decision-making emerges from interactions between multiple neural accumulators operating on different principles.

Episodic Memory Signatures

Research on gray matter signatures of episodic memory demonstrates the process of deriving and validating neuroimaging signatures:

Discovery Phase: Regional gray matter thickness associations are computed in multiple discovery cohorts using randomly selected subsets [1].

Consensus Generation: Spatial overlap frequency maps are created, with high-frequency regions defined as consensus signature masks [1].

Validation: Consensus models are tested in independent cohorts for replicability and explanatory power [1].

This approach has produced signature models that replicate model fits to outcome and outperform other commonly used measures [1], suggesting strongly shared brain substrates for memory functions.

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Translation

Neuroimaging in Neuroscience R&D

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly leverages neuroimaging to accelerate neuroscience research and development:

Target Engagement: Using PET and MRI to verify that therapeutic compounds reach intended brain targets and produce desired physiological effects [18].

Patient Stratification: Identifying distinct patient subgroups based on brain signatures for more targeted clinical trials [18].

Treatment Response Monitoring: Objectively measuring changes in brain structure or function in response to interventions [18].

Mechanism Elucidation: Uncovering how investigational medicines affect brain networks and pathways [18].

In Alzheimer's disease research, for example, MRI characterizes structural changes like brain atrophy, while PET imaging visualizes molecular targets like amyloid plaques and tau tangles [18]. These applications directly build on understanding the relationship between microscopic pathology and macroscopic imaging signatures.

Biomarkers in Clinical Trials

The role of biomarkers in neurological drug development has expanded significantly:

Eligibility Determination: Biomarkers identify appropriate participants for clinical trials, particularly important for diseases with complex presentations [19].

Outcome Measures: Biomarkers serve as primary or secondary endpoints in 27% of active Alzheimer's trials, providing objective measures of treatment efficacy [19].

Pharmacodynamic Assessment: Measuring target engagement and biological responses to therapeutic interventions [19].

The 2025 Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline includes 182 trials with 138 drugs, with biomarkers playing crucial roles across all phases [19]. This represents a significant increase from previous years, reflecting growing recognition of their importance.

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Coding and Neuroimaging Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Models | Poisson Mixture Models [16], Conway-Maxwell-Poisson Distributions [16], Drift-Diffusion Models [17] | Capture neural variability and covariability; link neural activity to behavior |

| Imaging Technologies | Two-photon microscopy [15], MRI [18], PET (amyloid and tau) [18] | Measure neural population activity (microscopic) and brain-wide signatures (macroscopic) |

| Analysis Frameworks | Exponential family distributions [16], Bayesian decoding [16], Cross-validated feature selection [1] | Quantify coding properties; validate signatures across cohorts |

| Behavioral Measures | Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales [1], Everyday Cognition scales [1] | Link neural and imaging data to cognitive outcomes |

| Validation Approaches | Consensus mask generation [1], Cross-cohort replication [1], Model fit comparison [1] | Ensure robustness and generalizability of findings |

Integrated Workflow: From Neural Recording to Validated Signature

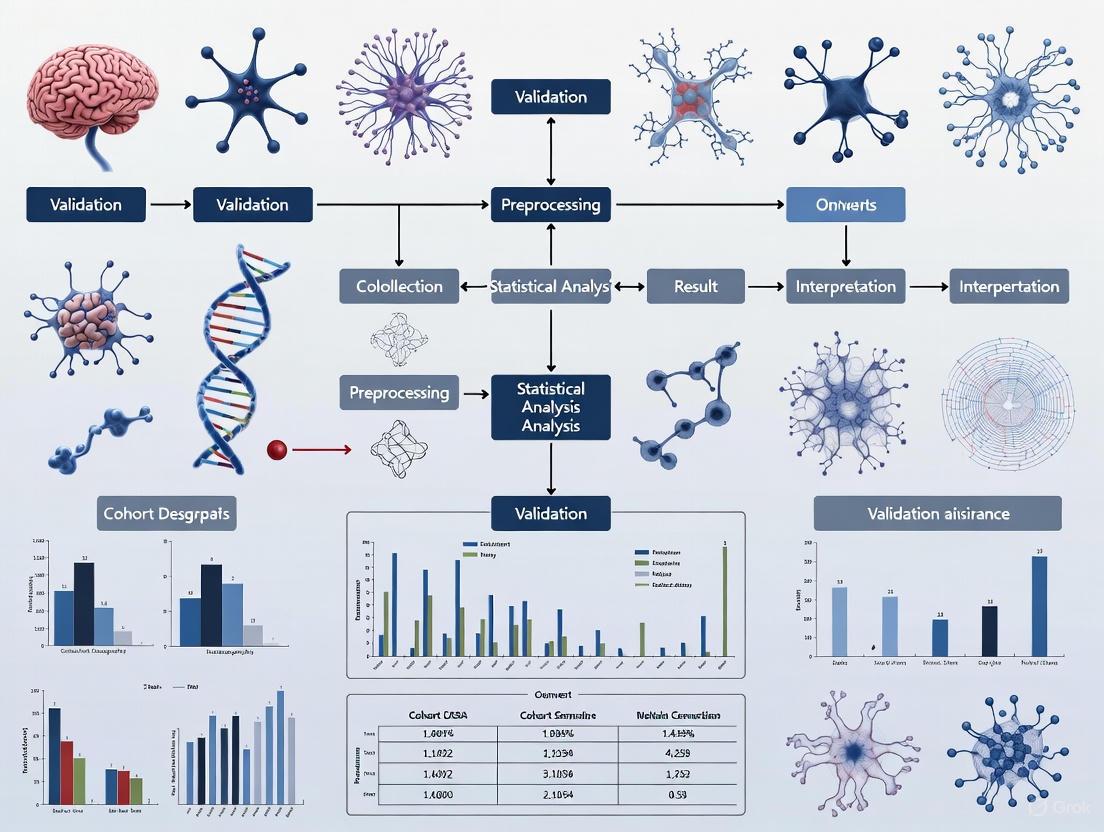

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental and analytical pipeline for linking neural population coding to validated neuroimaging signatures:

The integration of neural population coding theories with neuroimaging signature validation represents a promising frontier in neuroscience. Several emerging trends will likely shape future research:

Multi-Scale Integration: Combining insights across spatial and temporal scales through more sophisticated computational models that explicitly bridge micro-, meso-, and macro-scale observations [15].

Advanced Computational Methods: Leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence to identify complex, nonlinear relationships in large-scale neural and imaging datasets [18] [20].

Standardized Validation Frameworks: Developing consensus approaches for statistical validation of brain signatures across diverse populations to ensure robustness and clinical utility [1].

Open Data Initiatives: Addressing the need for large datasets through collaborative efforts like the U.K. Biobank, which provide the sample sizes necessary for reproducible signature discovery [1].

The connection between population neural coding and neuroimaging signatures continues to evolve rapidly, offering new avenues for understanding brain function and developing targeted interventions for neurological disorders. As these fields mature, the emphasis on rigorous statistical validation across multiple cohorts will be essential for translating theoretical insights into clinically meaningful advances.

The core objective of maximizing the characterization of brain-behavior substrates centers on the development and validation of robust brain signatures—multivariate, data-driven patterns of brain structure or function that are systematically associated with behavioral or cognitive domains [1]. This approach represents an evolution from theory-driven or lesion-based models, aiming to provide a more complete accounting of the complex brain substrates underlying behavioral outcomes [1]. The fundamental challenge in this pursuit is ensuring that these signatures are not only statistically significant within a single dataset but also reproducible and generalizable across diverse populations, imaging protocols, and research sites [21]. The validation of brain signatures across multiple cohorts has emerged as a critical methodological imperative, separating potentially useful biomarkers from findings limited to specific samples or study conditions [1] [21].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of methodological approaches for developing and validating brain-behavior signatures, detailing experimental protocols, and presenting performance data across different validation frameworks. We focus specifically on the statistical rigor required to transition from promising initial findings to clinically relevant biomarkers for drug development and therapeutic targeting.

Comparative Analysis of Brain Signature Approaches

The table below compares three primary methodological frameworks for identifying brain-behavior relationships, highlighting their core principles, validation requirements, and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodological Approaches for Brain-Behavior Signatures

| Methodological Approach | Core Analytical Principle | Validation Paradigm | Reported Performance & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gray Matter Morphometry Signatures [1] | Data-driven voxel-wise regression to identify regional gray matter thickness associations with behavior. | Multi-cohort consensus masks with hold-out validation. | High replicability of model fits (high correlation in validation subsets); outperformed theory-based models [1]. |

| Multivariate Canonical Correlation [21] | Sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (SCCA) to identify linear combinations of brain connectivity features that correlate with behavior combinations. | Internal cross-validation and external out-of-study validation. | Consistent internal generalizability in ABCD study; limited out-of-study generalizability in Generation R cohort [21]. |

| High-Order Functional Connectivity [22] | Information-theoretic analysis (O-Information) to detect synergistic interactions in brain networks beyond pairwise correlations. | Single-subject surrogate and bootstrap data analysis. | Reveals significant high-order, synergistic subsystems missed by pairwise analysis; allows subject-specific inference [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Signature Validation

Multi-Cohort Consensus Masking for Structural Signatures

This protocol, as implemented for gray matter signatures of memory, involves a rigorous two-stage discovery and validation process [1].

Discovery Phase:

- Cohort Selection: Utilize large, cognitively diverse discovery cohorts (e.g., n=578 from UCD ADRC, n=831 from ADNI 3) [1].

- Subsampling and Feature Identification: Repeatedly (e.g., 40 times) randomly select subsets (e.g., n=400) from the discovery cohort. In each subset, compute voxel-wise associations between gray matter thickness and the behavioral outcome (e.g., episodic memory score) [1].

- Consensus Mask Generation: Generate spatial overlap frequency maps from all subsampling iterations. Define high-frequency regions as a "consensus" signature mask, ensuring spatial reproducibility [1].

Validation Phase:

- Independent Validation Cohorts: Apply the consensus signature mask to entirely separate validation datasets (e.g., n=348 from UCD, n=435 from ADNI 1) not used in discovery [1].

- Model Fit Replicability: Evaluate the signature's performance by testing the correlation of its model fits to the behavioral outcome across many random subsets (e.g., 50) of the validation cohort [1].

- Explanatory Power Comparison: Compare the signature model's explanatory power against competing theory-based models (e.g., predefined ROI-based models) on the full validation cohort [1].

Doubly Multivariate Validation for Brain-Behavior Dimensions

This protocol uses SCCA to identify dimensions linking brain functional connectivity to multiple psychiatric symptoms, with a focus on generalizability testing [21].

Analysis Workflow:

- Input Data: Resting-state functional connectivity matrices and multi-scale behavioral symptom data (e.g., from the Child Behavior Checklist) [21].

- Model Training (Discovery): Apply SCCA in a large discovery cohort (e.g., ABCD Study, n=4892) under a rigorous multiple hold-out framework to identify canonical variates (brain-behavior dimensions) and train a predictive model [21].

- Internal Validation: Assess model performance on held-out test data from the same study to ensure internal robustness [21].

- External Validation (Generalizability Test): Apply the exact same trained model to a completely independent dataset (e.g., Generation R Study, n=2043) with different sampling and methodological protocols. Evaluate the degradation in performance to test true out-of-study generalizability [21].

Single-Subject High-Order Interaction Analysis

This protocol statistically validates high-order brain connectivity patterns on an individual level, which is crucial for clinical translation [22].

Statistical Testing Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Extract multivariate resting-state fMRI time series from multiple brain regions of interest for a single subject [22].

- Pairwise Connectivity Significance:

- Calculate pairwise Mutual Information (MI) between all region pairs.

- Generate surrogate time series that mimic individual signal properties but are otherwise uncoupled.

- Compare the actual MI values against the null distribution from surrogates to identify statistically significant pairwise connections [22].

- High-Order Interaction (HOI) Assessment:

- Compute the O-Information (OI) statistic to quantify whether a group of three or more brain regions shares information redundantly or synergistically.

- Use a bootstrap procedure (resampling with replacement) to generate confidence intervals for the OI estimate.

- Determine the significance of HOIs by checking if confidence intervals exclude zero, and compare OI values across different conditions (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment) for the same subject [22].

Diagram 1: Single-subject high-order connectivity validation workflow.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key methodological "reagents" — the essential analytical tools and resources required for conducting robust brain signature research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Brain Signature Validation

| Research Reagent | Function & Role in Validation |

|---|---|

| Independent Multi-Site Cohorts | Provides the fundamental biological material for testing generalizability across different scanners, populations, and protocols. Serves as the ultimate test for a signature's robustness [1] [21] [23]. |

| High-Quality Brain Parcellation Atlases | Standardized anatomical frameworks for defining features (e.g., regions of interest). Ensures consistency and comparability of features across different studies and analyses [1]. |

| Sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (SCCA) | A key algorithmic reagent for identifying multivariate brain-behavior dimensions. Its built-in feature selection helps prevent overfitting, making derived dimensions more interpretable and potentially more generalizable [21]. |

| Surrogate & Bootstrap Data Algorithms | Computational reagents for statistical testing at the single-subject level. Surrogates test for significant coupling, while bootstrapping generates confidence intervals, enabling inference for individual cases [22]. |

| Consensus Mask Generation Pipeline | A computational workflow that aggregates results from multiple discovery subsamples. This reagent mitigates the pitfall of deriving signatures from a single, potentially non-representative sample, enhancing spatial reproducibility [1]. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The logical progression from discovery to a clinically generalizable biomarker involves multiple validation gates. The following diagram maps this pathway and highlights critical points where promising signatures may fail.

Diagram 2: The validation pathway for generalizable brain biomarkers.

Building Robust Signatures: Methodologies for Discovery and Multi-Cohort Application

The quest to identify robust brain signatures of cognition and disease represents a major focus in modern neuroimaging research. A crucial step in this process is feature selection—the identification of key neural features most predictive of behavioral outcomes or clinical conditions. This guide provides an objective comparison of two predominant methodological families: traditional voxel-based regressions and advanced machine learning (ML) approaches. With brain signatures increasingly considered as potential biomarkers for drug development and clinical trials, understanding the performance characteristics, validation requirements, and practical implementation of these methods is essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

The validation of brain signatures requires rigorous demonstration of both model fit and spatial replicability across multiple cohorts [1]. This methodological comparison is framed within this critical context, examining how each approach addresses challenges such as high-dimensional data (where features far exceed samples), multiple testing corrections, and generalization across diverse populations.

Voxel-Based Regression Approaches

Voxel-based regression methods represent a data-driven, exploratory approach to identifying brain-behavior relationships without relying on predefined regions of interest. These techniques compute associations between gray matter thickness or other voxel-wise measurements and behavioral outcomes across the entire brain [1].

The signature approach developed by Fletcher et al. exemplifies a rigorous implementation. This method involves deriving regional brain gray matter thickness associations for specific domains (e.g., neuropsychological and everyday cognition memory) across multiple discovery cohorts. Researchers compute regional associations to outcomes in numerous randomly selected discovery subsets, then generate spatial overlap frequency maps. High-frequency regions are defined as "consensus" signature masks, which are subsequently validated in separate datasets to evaluate replicability of model fits and explanatory power [1].

A key strength of this approach is its ability to detect brain-behavior associations that may cross traditional ROI boundaries, potentially providing more complete accounting of neural substrates than atlas-based methods [1]. However, pitfalls include inflated association strengths and lost reproducibility when discovery sets are too small, with studies suggesting sample sizes in the thousands may be needed for robust replicability [1].

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning approaches employ algorithmic feature selection to identify multivariate patterns in neuroimaging data that predict outcomes of interest. These methods are particularly valuable for high-dimensional data where traditional statistical methods may struggle.

Common ML Feature Selection Techniques

Regularization Methods: Techniques like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) apply penalties during model fitting to shrink coefficients of irrelevant features to zero, effectively performing feature selection [24]. The Sparsity-Ranked LASSO (SRL) modification incorporates prior beliefs that task-relevant signals are more concentrated in components explaining greater variance [24].

Hybrid Methods: The Joint Sparsity-Ranked LASSO (JSRL) combines sparsity-ranked principal component data with voxel-level activation, integrating component-level and voxel-level activity under an information parity framework [24].

Stability-Based Selection: Some frameworks apply multiple filter, wrapper, and embedded methods sequentially. One approach first screens features using statistical tests, removes redundant features via correlation analysis, then applies embedded selection methods like LASSO or Random Forests to identify final feature sets [25].

Multi-Task Feature Selection: For complex disorders like schizophrenia, robust multi-task feature selection frameworks based on optimization algorithms like Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) can identify abnormal functional connectivity features across multiple datasets [26].

Discrimination vs. Reliability Criteria

Feature selection criteria generally fall into two categories: discrimination-based feature selection (DFS), which prioritizes features that maximize distinction between brain states, and reliability-based feature selection (RFS), which selects stable features across samples [27]. Studies comparing these approaches found that DFS features generally offer better classification performance, while RFS features demonstrate greater stability across repeated screenings [27].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods Across Neuroimaging Applications

| Method | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Based Signature Regression | Episodic memory (gray matter thickness) | High replicability of model fits; Outperformed theory-based models [1] | Identifies cross-boundary associations; Rigorous multi-cohort validation |

| LASSO Principal Components Regression (PCR) | fMRI task classification (risk, incentive, emotion) | Baseline performance for comparison [24] | Standard approach; Good benchmark |

| Sparsity-Ranked LASSO (SRL) | fMRI task classification | 7.3% improvement in cross-validated AUC over LASSO PCR [24] | Incorporates variance-based weighting |

| Joint Sparsity-Ranked LASSO (JSRL) | fMRI task classification | Up to 51.7% improvement in cross-validated deviance [24] | Combines component + voxel level information |

| Robust Multi-Task Feature Selection + GWO | Schizophrenia identification (rs-fMRI) | Significantly outperformed existing methods in classification accuracy [26] | Multi-dataset robustness; Counterfactual explanations |

| Discrimination-Based Feature Selection | Task fMRI decoding (HCP data) | Better classification accuracy than reliability-based selection [27] | Optimized for brain state distinction |

| Reliability-Based Feature Selection | Task fMRI decoding (HCP data) | Greater feature stability than discrimination-based selection [27] | Reduced feature selection variability |

Validation Rigor and Generalizability

Table 2: Validation Approaches and Cohort Requirements

| Method | Typical Cohort Size | Validation Approach | Generalizability Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Based Signature Regression | 400-800 per discovery cohort [1] | Multi-cohort consensus + separate validation datasets [1] | High spatial replicability across cohorts |

| Flexible Radiomics Framework | Multiple real-world datasets [25] | Cross-validation with multiple embedded methods [25] | Tested across diverse clinical datasets |

| Multi-Task Feature Selection | 5 SZ datasets (120-311 subjects each) [26] | Cross-dataset validation with counterfactual explanation [26] | Identifies robust cross-dataset features |

| Small-Cohort ML Pipelines | 16 patients + 14 controls [28] | Limited by sample size despite pipeline optimization [28] | Highlights data quantity importance |

Implementation Considerations

Table 3: Practical Implementation Requirements

| Method | Computational Demand | Data Requirements | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel-Based Regression | Moderate (multiple subset analyses) [1] | Large cohorts for discovery and validation [1] | High (direct spatial interpretation) |

| LASSO PCR | Moderate | Standard fMRI preprocessing [24] | Moderate (component to voxel mapping) |

| Advanced ML (JSRL, GWO) | High (hybrid models, optimization) [26] [24] | Multiple datasets for robust feature selection [26] | Variable (may require explanation models) |

| Flexible Feature Selection Framework | Moderate (sequential filtering) [25] | Adaptable to various dataset sizes [25] | High (transparent selection process) |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Voxel-Based Signature Validation Protocol

The validation protocol for voxel-based signature regression involves a rigorous multi-cohort approach [1]:

- Discovery Phase: Derive regional brain gray matter thickness associations for specific behavioral domains in multiple discovery cohorts

- Consensus Generation: Compute regional associations in multiple randomly selected discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of size 400)

- Spatial Mapping: Generate spatial overlap frequency maps and define high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks

- Validation: Evaluate replicability using separate validation datasets, comparing signature model fits with theory-based models

- Performance Assessment: Compare explanatory power and model fit correlations across validation cohorts

This protocol emphasizes the importance of large sample sizes, with studies suggesting thousands of participants may be needed for robust replicability [1].

Figure 1: Voxel-Based Signature Development and Validation Workflow

Hybrid Machine Learning Pipeline

Advanced ML approaches for fMRI data often combine multiple feature selection strategies:

- Data Preprocessing: Construct functional connectivity matrices from rs-fMRI data and extract feature vectors [26]

- Initial Feature Screening: Apply statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U) to identify significantly different features between groups [29]

- Redundancy Reduction: Remove highly correlated features (e.g., absolute correlation threshold of 0.65) [29]

- Advanced Selection: Apply regularized methods (LASSO, Elastic-Net) or multi-task optimization to select final feature sets [26] [25]

- Model Building & Validation: Train classifiers (SVM, Random Forest) using selected features and validate performance in test datasets [29]

The JSRL method specifically incorporates sparsity ranking by assigning penalty weights based on principal component indices, reflecting prior information about where task-relevant signals are likely concentrated [24].

Figure 2: Machine Learning Feature Selection Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Data-Driven Feature Selection

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Platforms | R, Python (scikit-learn), SPSS | Implementation of statistical tests and basic ML algorithms | R/Python preferred for customization; extensive library support |

| Neuroimaging Suites | FSL, SPM, AFNI, RESTplus [29] | Image preprocessing, normalization, basic feature extraction | RESTplus used for rs-fMRI preprocessing including ALFF, ReHo, PerAF [29] |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | LASSO, Elastic-Net, Gray Wolf Optimizer [26], Boruta | Dimensionality reduction and feature subset selection | GWO simulates wolf pack hunting behavior for multi-task optimization [26] |

| Validation Frameworks | Cross-validation, nested CV, multi-cohort validation [1] | Performance assessment and overfitting prevention | Nested CV essential for small cohorts; multi-cohort preferred when possible |

| Interpretation Tools | Guided backpropagation [30], counterfactual explanations [26] | Model interpretation and clinical translation | Counterfactuals show how altering features changes predictions [26] |

| Atlas Resources | AAL, JHU, BRO, AICHA atlases [31] | Brain parcellation for feature definition | JHU atlas often optimal for language outcomes [31] |

| Performance Metrics | AUC, MAE, cross-validated deviance, spatial replicability | Method comparison and validation | Multi-metric assessment recommended (accuracy, stability, interpretability) |

The comparison between voxel-based regressions and machine learning approaches for feature selection in neuroimaging reveals a complex trade-off between interpretability, performance, and implementation requirements. Voxel-based methods offer high spatial interpretability and established validation pathways but require large cohorts for robust discovery. Machine learning approaches provide superior flexibility and can handle complex multivariate patterns, with advanced methods like JSRL and multi-task feature selection demonstrating significant performance improvements.

For researchers and drug development professionals, method selection should be guided by specific research goals, cohort characteristics, and validation resources. Voxel-based signature regression remains valuable for well-powered studies seeking spatially interpretable biomarkers, particularly when cross-cohort validation is feasible. Machine learning approaches offer advantages for complex pattern detection and smaller sample sizes, though they require careful attention to interpretation and validation.

The emerging trend toward hybrid methods that combine strengths from both approaches—such as JSRL's integration of component-level and voxel-level information—represents a promising direction for developing more robust, interpretable, and clinically useful brain signatures in neuroimaging research.

The pursuit of robust brain signatures—data-driven maps of brain regions most strongly associated with specific cognitive functions or diseases—faces a central challenge: ensuring these signatures generalize across diverse populations and study designs. The multi-cohort aggregation method has emerged as a powerful solution, leveraging multiple independent datasets to generate consensus signature masks that overcome limitations of single-cohort studies. This approach employs rigorous statistical validation to identify reproducible brain-behavior relationships, enhancing the reliability of biomarkers for conditions like Alzheimer's disease and cognitive impairment. By systematically comparing this methodology against alternative approaches, this guide provides researchers with evidence-based protocols for implementing multi-cohort aggregation in neuroimaging studies, with particular relevance for drug development professionals seeking validated endpoints for clinical trials.

A brain signature represents a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions most strongly associated with specific cognitive functions or behavioral outcomes. Unlike theory-driven approaches that rely on pre-specified regions of interest, signature methods select features based solely on performance metrics of prediction or classification, with the potential to maximally characterize brain substrates of behavioral outcomes [1] [32]. The fundamental challenge in signature development is robust validation across multiple cohorts to ensure generalizability beyond the discovery dataset.

The multi-cohort aggregation method addresses several critical limitations in neuroimaging research:

- Cohort-specific biases: Individual studies are subject to specific inclusion criteria, measurement protocols, and population characteristics that can limit generalizability [33].

- Limited statistical power: Single cohorts may lack sufficient sample sizes to detect subtle but consistent brain-behavior relationships [1].

- Heterogeneous signatures: Models derived from different cohorts may show varying regional patterns despite measuring the same underlying construct [32].

Multi-cohort approaches overcome these limitations by aggregating information across independent studies, enhancing confidence in replicability and producing more reliable measures for modeling behavioral domains [1] [34]. This is particularly valuable in drug development, where robust biomarkers can inform target identification, patient stratification, and treatment response monitoring.

Comparative Analysis of Signature Generation Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Signature Generation Methodologies

| Method | Core Approach | Validation Strategy | Key Advantages | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cohort Aggregation | Derives consensus masks from multiple discovery cohorts using spatial overlap frequency [1] | Separate validation datasets; correlation of model fits across random subsets [1] | High replicability; robust to cohort-specific biases; outperforms theory-based models | High replicability correlation; superior explanatory power vs. alternatives [1] |

| Event-Based Modeling with Rank Aggregation | Creates meta-sequence from partially overlapping individual event sequences [33] | Consistency assessment across cohorts (Kendall's tau correlation) [33] | Combines complementary information; handles different measured variables across cohorts | Average pairwise Kendall's tau: 0.69 ± 0.28 [33] |

| Multi-Cohort Machine Learning | Trains models across multiple cohorts to predict clinical outcomes [35] | Hold-out testing across cohorts; stability analysis across cross-validation cycles [35] | Greater performance stability; identifies consistent predictors; handles heterogeneous populations | AUC: 0.67-0.72; C-index: 0.65-0.72; improved stability [35] |

| Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration | Identifies network-based signatures integrating unmatched molecular data [36] | Prognostic prediction in independent validation cohorts; comparison to existing signatures [36] | Captures data heterogeneity across omics layers; utilizes publicly available data | Significant separation of survival curves; outperforms existing signatures [36] |

| Single-Cohort Voxel-Aggregation | Voxel-wise regression within a single cohort to generate signature masks [32] | Cross-validation in independent cohorts; comparison to theory-driven models [32] | "Non-standard" regions not conforming to atlas parcellations; easily computed | Adjusted R²: similar performance across cohorts; outperforms theory-driven models [32] |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

| Method | Sample Sizes (Discovery/Validation) | Primary Outcome Domain | Key Performance Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cohort Aggregation | 400 random subsets in each of 2 discovery cohorts; 50 random subsets in validation [1] | Episodic memory; everyday memory | High replicability of model fits; outperformed competing theory-based models [1] |

| Event-Based Modeling with Rank Aggregation | 10 cohorts totaling 1,976 participants [33] | Alzheimer's disease progression staging | Consistent disease cascades across cohorts (0.69 ± 0.28 Kendall's tau) [33] |

| Multi-Cohort Machine Learning | 3 cohorts (LuxPARK, PPMI, ICEBERG) [35] | Parkinson's disease cognitive impairment | Multi-cohort models showed greater stability than single-cohort; AUC: 0.67-0.72 [35] |

| Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration | 9 GBM (n=622) and 8 LGG (n=1,787) datasets; 1,269 validation samples [36] | Glioblastoma and low-grade glioma survival prediction | Significant separation of survival curves (Cox p-values); outperformed 10 existing signatures [36] |

| Single-Cohort Voxel-Aggregation | 3 non-overlapping cohorts (n=255, 379, 680) [32] | Episodic memory baseline and change | Signature ROIs generated in one cohort replicated performance level in other cohorts [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Cohort Aggregation

Core Workflow for Consensus Signature Generation

The multi-cohort aggregation method follows a structured workflow to generate consensus signature masks:

Cohort Selection and Harmonization

Discovery Phase with Multiple Subsets

- Randomly select multiple discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of size 400) from each cohort [1]

- For each subset, compute voxel-wise associations between brain structure (e.g., gray matter thickness) and behavioral outcomes [1]

- Use regression analysis with appropriate multiple comparisons correction [32]

Spatial Overlap Frequency Mapping

Validation in Independent Datasets

Technical Implementation Details

Key Analytical Considerations

Spatial Overlap Thresholds: Determining appropriate frequency thresholds for consensus region definition involves balancing sensitivity and specificity. Higher thresholds produce more specific but potentially incomplete signatures, while lower thresholds may include noisy regions [1].

Cross-Cohort Normalization: When combining data across cohorts, appropriate normalization methods must address technical variability while preserving biological signals. Comparative evaluations of normalization approaches can identify optimal strategies for specific data types [35].

Handling Missing Data: Different cohorts often measure partially overlapping variable sets. Rank aggregation methods can combine complementary information across cohorts without requiring complete data on all variables for all participants [33].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Multi-Cohort Signature Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Cohorts | ADNI [1] [32]; UCD Aging and Diversity Cohort [1] [32]; LuxPARK, PPMI, ICEBERG [35] | Provide diverse, well-characterized datasets for discovery and validation | Ensure appropriate data use agreements; address ethnic and clinical diversity gaps |

| Cognitive Assessments | Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales (SENAS) [1]; Everyday Cognition scales (ECog) [1]; Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [35] | Standardized measurement of behavioral outcomes of interest | Consider cross-cultural validation; assess both objective and subjective cognitive measures [35] |

| Image Processing Pipelines | Custom in-house pipelines [1]; Freesurfer [32] | Volumetric segmentation and cortical thickness measurement | Implement rigorous quality control; address scanner and protocol variability |

| Statistical Analysis Platforms | R packages ("ConsensusClusterPlus" [37], "timeROC" [37], "glmnet" [37]); Python machine learning libraries [35] | Implement multi-cohort aggregation algorithms and validation procedures | Ensure reproducibility through version control and containerization |

| Multi-Omics Databases | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [37] [36]; Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [37] [36] | Provide molecular data for network-based signature development [36] | Address batch effects and platform differences when integrating diverse datasets |

Comparative Performance in Neurodegenerative Disease Applications

Alzheimer's Disease and Cognitive Aging

In Alzheimer's disease research, multi-cohort aggregation has demonstrated particular utility for identifying robust signatures of episodic memory—a key cognitive domain affected in both normal aging and Alzheimer's pathology. Fletcher et al. demonstrated that signature region of interest models generated using multi-cohort aggregation replicated their performance level when explaining cognitive outcomes in separate cohorts, outperforming theory-driven models based on pre-specified regions [32]. The method successfully identified convergent consensus signature regions across independent discovery cohorts, with signature model fits highly correlated across random validation subsets [1].

Parkinson's Disease Cognitive Impairment

For Parkinson's disease, multi-cohort machine learning approaches have identified robust predictors of cognitive impairment, with age at diagnosis and visuospatial ability emerging as key predictors across diverse populations [35]. Multi-cohort models showed greater performance stability compared to single-cohort models while retaining competitive average performance, highlighting the value of aggregated approaches for developing reliable predictive tools [35].

Comparative Robustness Assessment

Implementation Guidelines and Future Directions

Recommended Best Practices

Based on comparative performance evidence, researchers implementing multi-cohort aggregation should:

Prioritize Cohort Diversity: Select discovery cohorts that encompass the full spectrum of population variability in terms of demographics, disease severity, and technical measurements [1] [34].

Implement Rigorous Validation: Use completely independent validation cohorts rather than data-splitting within cohorts to obtain unbiased performance estimates [1] [32].

Address Batch Effects Systematically: Apply cross-study normalization methods that account for technical variability while preserving biological signals [35].

Benchmark Against Alternatives: Compare multi-cohort aggregation performance against theory-driven and other data-driven approaches to establish comparative utility [1] [32].

Emerging Methodological Innovations

Future developments in multi-cohort aggregation are likely to focus on:

Cross-Disorder Signatures: Applying aggregation methods to identify transdiagnostic brain signatures across multiple neurological and psychiatric conditions [36].

Dynamic Signature Mapping: Extending the approach to capture temporal dynamics of brain-behavior relationships through longitudinal multi-coort designs [32].

Multi-Modal Integration: Combining structural, functional, and molecular imaging modalities within unified aggregation frameworks [36].

Federated Learning Approaches: Developing privacy-preserving methods that enable signature generation without sharing raw data across sites [35].

For drug development professionals, multi-cohort aggregation offers a pathway to more reliable biomarkers for patient stratification, target engagement assessment, and treatment response prediction. The method's robustness across diverse populations enhances its utility for designing clinical trials with greater sensitivity to detect treatment effects.

Leverage-Score Sampling and Other Techniques for Individual-Specific Signatures

The pursuit of individual-specific signatures—unique, reproducible biomarkers of an individual's biological or physiological state—represents a frontier in precision medicine and neuroscience. These signatures hold the potential to transform healthcare by enabling highly personalized diagnostics, monitoring, and therapeutic interventions. In neuroscience, functional connectomes derived from neuroimaging have been shown to be unique to individuals, with scans from the same subject being more similar than those from different subjects [38]. Beyond the brain, individual-specific signatures have also been demonstrated in circulating proteomes, where plasma protein profiles exhibit remarkable individuality that persists over time [39].

The statistical validation of these signatures across multiple cohorts presents significant methodological challenges. The high-dimensional nature of neuroimaging and molecular data, combined with the need for robustness across diverse populations, requires sophisticated computational approaches for feature selection and dimensionality reduction. Among these techniques, leverage-score sampling has emerged as a powerful framework for identifying compact, informative feature sets that capture individual-specific patterns while maintaining interpretability [38] [40].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of leverage-score sampling and other prominent techniques for deriving individual-specific signatures, with a focus on applications in brain signature research. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks to help researchers select appropriate methods for their specific validation challenges.

Techniques for Signature Identification: Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Signature Identification Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Data Type | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|