The Lesion Method: A Foundational Tool for Causal Brain-Behavior Mapping in Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the lesion method, a cornerstone technique in neuroscience for establishing causal links between brain structure and function.

The Lesion Method: A Foundational Tool for Causal Brain-Behavior Mapping in Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the lesion method, a cornerstone technique in neuroscience for establishing causal links between brain structure and function. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the method's historical foundations and evolution, detailing its transition from classic case studies to modern, computationally-driven approaches like voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM). The scope encompasses core methodologies, practical applications across cognitive and clinical domains, strategies for overcoming limitations such as lesion heterogeneity and compensatory plasticity, and a comparative evaluation against other neuroimaging and neuromodulation techniques. By synthesizing recent advances and future directions, this review underscores the method's indispensable role in validating therapeutic targets and informing clinical translation.

From Phineas Gage to VLSM: The History and Core Principles of Brain Lesion Studies

The lesion method is a foundational scientific approach that studies the relationship between brain and behavior by examining changes in cognitive, emotional, or behavioral functions following focal brain damage. This method operates on the causal inference principle that if a lesion in brain structure X leads to a deficit in function Y, then X is necessary for Y. Unlike correlational neuroimaging methods, the lesion method provides stronger causal inference about brain function because the brain damage precedes and causes the behavioral changes observed. Historically, studies of individual patients with brain lesions have provided groundbreaking insights into how the brain gives rise to behavior, forming the bedrock of modern cognitive neuroscience [1].

Table 1: Foundational Historical Cases in the Lesion Method

| Patient/Case | Year | Brain Area Affected | Functional Deficit Observed | Scientific Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phineas Gage | 1848 | Frontal Lobe | Profound personality changes; became irritable, impulsive, and disinhibited | First evidence linking frontal lobes to personality and executive function [1] |

| Louis Victor Leborgne ("Tan") | 1861 | Left Inferior Frontal Lobe (Broca's area) | Severe speech production deficit; could only say the word "tan" | Identified a brain region critical for speech production (Broca's aphasia) [1] |

| Susanne Adam | 1874 | Left Posterior Temporal Lobe (Wernicke's area) | Impaired speech comprehension; fluent but nonsensical speech | Identified a brain region critical for language comprehension (Wernicke's aphasia) [1] |

| Henry Molaison (H.M.) | 1953 | Bilateral Medial Temporal Lobes (Hippocampus) | Severe anterograde amnesia; inability to form new declarative memories | Established the critical role of the hippocampus in memory formation [1] |

| Patient S.M. | 1994 | Bilateral Amygdala | Profound lack of fear; inability to recognize fear in others | Demonstrated the amygdala's essential role in processing fear and related emotions [1] |

Modern Methodological Evolution

Contemporary lesion method research has evolved from single-case studies to sophisticated group studies and computational techniques that map symptoms onto brain circuits. A significant modern advancement is lesion network mapping, which recognizes that many brain functions do not localize to a single region but depend on distributed circuits of connected areas. This technique identifies brain networks involved in complex symptomatology by mapping lesion locations onto large-scale brain connectome data. This approach can identify consistent brain networks underlying specific symptoms, even when the lesions themselves occur in different anatomical locations [2].

This "bedside-to-bedside" pathway offers a potentially shorter route to developing targeted therapies for neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. By identifying the neuroanatomical basis of quantifiable symptoms across clinical cohorts, researchers can generate circuit-based hypotheses. These hypotheses can then be validated in large-scale cohorts and prospectively tested using non-invasive neuromodulation techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), leading directly to clinical trials for symptom-based therapy [2].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Single-Case Study and Deep Phenotyping

Objective: To establish a direct causal link between a specific, focal brain lesion and a resulting behavioral or cognitive deficit in an individual patient.

Materials: High-resolution structural MRI or CT scanner, standardized neuropsychological assessment battery, clinical interview protocols, video recording equipment (if applicable for behavioral analysis).

Procedure:

- Case Identification & Characterization: Identify a patient with a focal, acquired brain lesion (e.g., from stroke, trauma, or surgical resection). Document the acute onset and nature of the behavioral change.

- Lesion Localization:

- Acquire a high-resolution T1-weighted structural MRI or CT scan.

- Trace the lesion boundaries manually on the individual's native brain scan using neuroimaging software (e.g., MRIcron, ITK-SNAP).

- If possible, normalize the lesioned brain to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI) to facilitate group comparisons or network mapping in future analyses.

- Behavioral/Cognitive Phenotyping:

- Administer a comprehensive, standardized neuropsychological assessment tailored to the hypothesized functional domain (e.g., aphasia battery for language deficits, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test for executive function).

- Conduct qualitative behavioral observation and structured interviews to document real-world functional impairments.

- Data Integration and Inference:

- Overlay the precisely mapped lesion location with the detailed behavioral profile.

- Infer that the lesioned brain area is critically necessary for the impaired function, as the deficit was absent prior to the injury and immediately followed it [1].

Protocol for Group Lesion-Symptom Mapping

Objective: To identify brain structures critical for a specific cognitive function by correlating lesion location with behavioral performance across a group of patients.

Materials: Cohort of patients with focal brain lesions, standardized behavioral task(s), computing resources with statistical software (e.g., R, MATLAB), lesion analysis toolbox (e.g., NiiStat, VLSM).

Procedure:

- Cohort Assembly: Recruit a group of patients with heterogeneous, focal brain lesions. Larger sample sizes (N > 50) increase statistical power and reproducibility [2].

- Lesion Data Processing:

- For each patient, trace the lesion on a T1-weighted MRI scan and normalize the brain to a standard template.

- Create a binary lesion map for each patient (1=voxel lesioned, 0=voxel intact).

- Behavioral Assessment: Administer the same quantitative behavioral task to all patients in the cohort. The task should be unidimensional and target a specific cognitive process (e.g., naming latency, memory accuracy, reaction time in a decision task).

- Statistical Mapping:

- Perform a voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM) analysis. At each voxel in the brain, a statistical test (e.g., t-test, Brunner-Munzel test) compares the behavioral scores of patients with a lesion at that voxel versus those without.

- The result is a statistical map of the brain showing regions where damage is significantly associated with poor performance on the task [2].

- Validation: Results can be validated by determining if the same brain network is implicated using lesion network mapping on independent connectome data [2].

Protocol for Lesion Network Mapping

Objective: To determine whether lesions causing a specific symptom map to a common functional brain network, even if they are anatomically distinct.

Materials: Database of lesioned patients with documented symptoms, resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) connectome database from healthy controls (e.g., Human Connectome Project), network mapping software.

Procedure:

- Define Seed Lesions: Identify a set of "seed" lesions from patients who all exhibit the same specific symptom (e.g., post-stroke tremor, inability to read).

- Network Identification:

- For each seed lesion location, identify the brain regions that are functionally connected to it using a normative connectome database derived from resting-state fMRI of healthy individuals.

- This step infers the brain network that was functionally disrupted by each lesion.

- Statistical Overlap Analysis:

- Test for significant overlap between the networks associated with all the seed lesions.

- The result is a common "symptom network" – a brain circuit that is functionally disrupted across all patients with the symptom, regardless of their exact lesion location [2].

- Cross-Disorder Validation: Test if this identified network is also relevant to idiopathic populations with the same symptom (e.g., in neurodevelopmental disorders) using traditional neuroimaging [2].

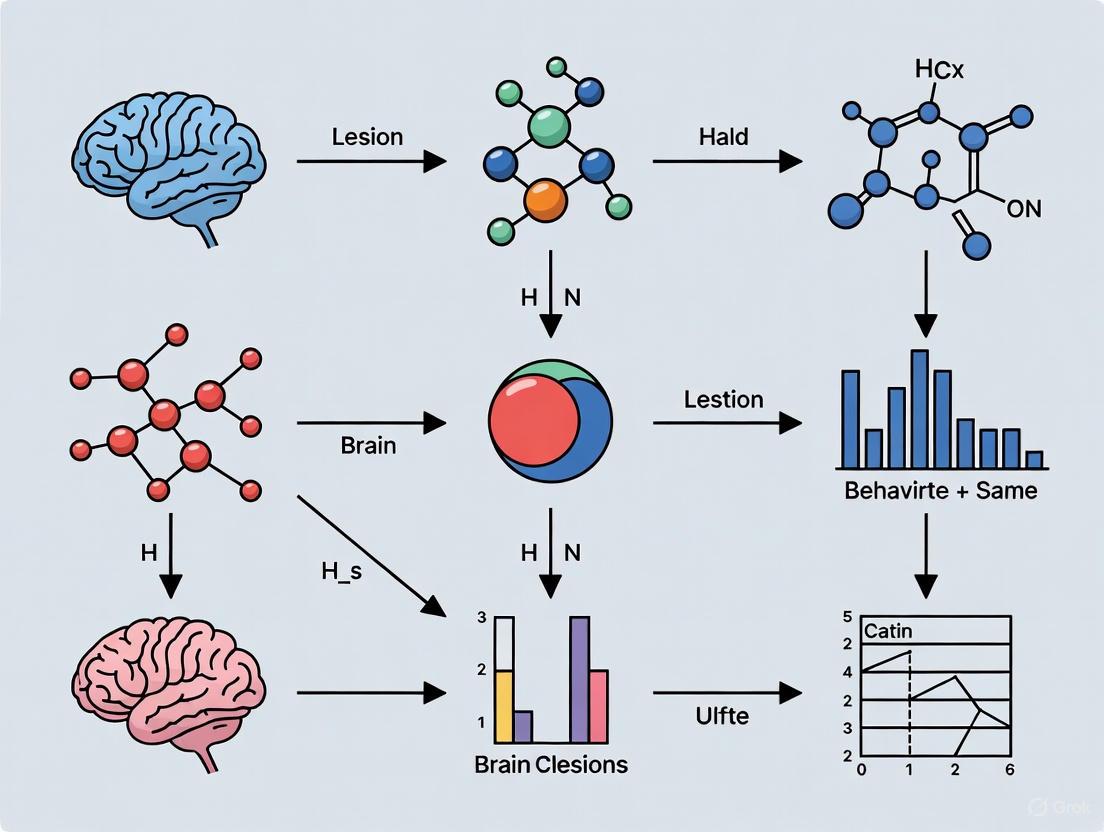

<75 chars Lesion Network Mapping Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Lesion Method Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Structural MRI (T1-weighted) | Provides the anatomical basis for precise, in-vivo lesion delineation and localization. The fundamental raw data for any modern lesion study [2]. |

| Standardized Neuropsychological Batteries | Quantifies behavioral and cognitive deficits in a reliable, validated manner, allowing for comparison across patients and studies (e.g., Boston Naming Test, WAIS). |

| Lesion Segmentation & Normalization Software (e.g., MRIcron, ITK-SNAP) | Allows researchers to manually trace lesion boundaries on individual brain scans and normalize them to a standard stereotaxic space for group-level analysis. |

| Normative Connectome Atlas (e.g., from HCP) | A database of functional connectivity patterns from a large cohort of healthy individuals. Serves as a reference map for the lesion network mapping technique [2]. |

| Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) Software | Performs voxel-wise statistical comparisons between lesion location and behavioral scores across a patient group to identify critically involved brain regions. |

| Non-Invasive Neuromodulation (TMS, tDCS) | Used to prospectively test hypotheses generated by lesion studies. Allows temporary, reversible "virtual lesions" or modulation of identified circuits to confirm causal roles [2] [3]. |

| Multimodal Imaging Integration (combining with fMRI, DTI) | Enhances causal inference from lesions by showing how a lesion disrupts functional activation or structural connectivity throughout a network during a task [3]. |

Integration with Neuromodulation and Causal Inference Challenges

The causal inferences drawn from the lesion method can be powerfully extended and tested using non-invasive neuromodulation techniques like repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS). rTMS can create temporary, reversible "virtual lesions" or enhance activity in brain areas identified by lesion studies. This allows for prospective, interventional testing of the causal hypotheses generated by observational lesion data [2] [3].

However, drawing direct causal inferences from both permanent lesions and rTMS involves logical and methodological challenges. A key limitation is that a change in behavior following stimulation of a brain area does not automatically mean that area's normal function is the direct cause of the behavior. The effect could be indirect, resulting from the propagation of the signal through a network or from side effects of the stimulation itself (e.g., auditory clicks, scalp sensations). Stronger causal inferences require careful control conditions, combination with neuroimaging to track network effects, and acknowledgment that brain functions emerge from distributed networks rather than isolated modules [3].

<75 chars Causal Inference Challenge in Intervention

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes of Modern Lesion-Based Therapeutic Development

| Therapeutic Approach | Target Symptom/Disorder | Key Circuit/Finding from Lesion Studies | Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive Neuromodulation (TMS/tDCS) [2] | Post-stroke motor recovery, depression, neurodevelopmental symptoms | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (for depression); Motor Network (for stroke) | Statistically significant improvement in standardized clinical rating scales (e.g., ~40-50% response rate in depression) |

| Real-time fMRI Neurofeedback [2] | Regulation of emotional or cognitive circuits | Targets identified as out-of-reach for TMS (e.g., deep limbic structures) | Successful learned modulation of target network activity; correlated symptomatic improvement |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Essential Tremor, Parkinson's Tremor | Thalamus (VIM nucleus) | Significant reduction (e.g., >50%) in tremor severity scores, validated across disorders [2] |

The foundational principle of correlating discrete brain lesions with specific behavioral deficits has been a cornerstone of cognitive neuroscience. The "lesion method" provides a powerful, natural experiment for inferring brain function, allowing researchers to make causal inferences about the neural substrates of behavior. This approach was pioneered through seminal case studies of patients with focal brain damage, including Broca's and Wernicke's aphasic patients and the profoundly amnesic patient H.M. Their unique neuropsychological profiles, resulting from specific brain lesions, revealed fundamental insights into the functional organization of language and memory systems. These historical cases continue to inform contemporary research methodologies and theoretical frameworks in cognitive neuroscience, establishing enduring principles about brain-behavior relationships that remain relevant for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand neural circuit functions.

Broca's Area: The Functional Anatomy of Speech Production

Historical Case Foundation

In 1861, Paul Broca described patient Leborgne ("Tan"), who exhibited severely non-fluent, effortful, and agrammatical speech despite relatively preserved language comprehension [4]. Postmortem examination revealed a lesion centered in the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIPC), a region now known as Broca's area (Brodmann areas 44 and 45) [5]. Broca's examination of approximately 20 additional patients with similar speech production deficits and left frontal damage led him to conclude that this region served as a critical center for articulate language [4]. This case established both the functional specialization of this cortical region and the principle of cerebral dominance for language, with the left hemisphere being dominant in most individuals.

Modern Re-evaluation and Protocol

Modern research using high-resolution structural and perfusion-weighted MRI in chronic stroke patients has confirmed that damage to the left inferior frontal cortex (particularly the pars opercularis, LIPCpo) more accurately predicts apraxia of speech (AOS) than damage to other regions like the insula [4]. The experimental protocol for establishing this correlation involves:

- Patient Selection: Recruit patients with chronic left hemisphere stroke (>6 months post-stroke) with and without motor speech impairment.

- Clinical Assessment: Administer standardized tests for apraxia of speech (AOS) and aphasia, generating both binary (present/absent) and continuous severity scores.

- Neuroimaging Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted structural MRI and pulsed arterial spin labeling (PASL) to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF).

- Lesion Demarcation: Manually trace lesions on native-space MRI images before spatial normalization to standard template (e.g., MNI space).

- Statistical Analysis: Perform whole-brain voxel-wise lesion-symptom mapping and stepwise regression analyzing proportional damage in regions of interest (ROI: LIPCpo, LIPCpt, left anterior/posterior insula).

Table 1: Quantitative Structural MRI Findings Linking Broca's Area to Speech Production

| Analysis Method | Key Brain Region | Statistical Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Voxel-Based Analysis | Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis (LIPCpo) | Z=3.66, p<0.01 | Damage to LIPCpo strongly predicts presence of AOS |

| Continuous Voxel-Based Analysis | Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis (LIPCpo) | Z=3.44, p<0.01 | Damage to LIPCpo strongly predicts severity of AOS |

| Stepwise Regression (Structural) | Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis (LIPCpo) | F(1,48)=79.802, p<0.0001, R²=0.62 | LIPCpo damage is the single best predictor of AOS |

| Stepwise Regression (CBF) | Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis (LIPCpo) | F(1,41)=15.431, p<0.0001, R²=0.273 | Reduced perfusion in LIPCpo predicts AOS |

Contemporary Insights from Intraoperative Mapping

Intraoperative Direct Electrical Stimulation (DES) during awake brain tumor surgery provides complementary evidence about Broca's area function. DES applied to Broca's area induces an intensity-dependent "speech arrest" without disrupting ongoing electromyography (EMG) activity in phono-articulatory muscles [6]. Quantitative EMG analysis (power spectrum and root mean square) shows no difference between baseline and stimulation periods during speech arrest [6]. This suggests Broca's area acts as a pre-articulatory phonetic encoder that gates motor program initiation rather than directly controlling muscle movement [6].

Figure 1: Broca's Area as a Pre-articulatory Gate: This model illustrates how Broca's area functions as a pre-articulatory encoder that gates the transition from language intention to motor execution. Direct Electrical Stimulation (DES) applied to this region prevents this gating function, resulting in speech arrest without affecting muscle activation patterns.

Wernicke's Area: Reinterpreting the Anatomy of Language Comprehension

Historical Context and Modern Challenges

In 1874, Carl Wernicke described a patient with fluent but meaningless speech and severe comprehension impairments, associating these deficits with a lesion in the left posterior superior temporal gyrus (pSTG) [7] [8]. This region, traditionally encompassing the posterior superior temporal gyrus and supramarginal gyrus (Brodmann areas 22, 40), became known as Wernicke's area and was historically defined as the cortical center for language comprehension [8]. Modern neuroimaging and lesion-symptom mapping studies in patients with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and stroke have challenged this classical model, demonstrating that severe word comprehension impairments are not reliably associated with damage to this anatomically-defined Wernicke's area [7].

Experimental Protocol for Comprehension Dissociation

Research dissociating word and sentence comprehension involves specific methodological approaches:

- Participant Cohort: 72 patients with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) of neurodegenerative origin provide a clean lesion-behavior model without sudden reorganization [7].

- Language Assessment: Comprehensive testing includes the Western Aphasia Battery (Aphasia Quotient ≥60), with specific measures for single-word comprehension (e.g., picture-word matching) and sentence comprehension (e.g., syntactic processing, commands) [7].

- Structural Imaging: High-resolution T1-weighted MRI acquired for voxel-based morphometry to quantify cortical atrophy.

- Clinico-Anatomical Correlation: Peak atrophy sites correlated with comprehension scores using voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping at individual and group levels [7].

Table 2: Dissociation of Comprehension Deficits Based on Lesion Location

| Comprehension Deficit | Associated Atrophy Site | Key Statistical Finding | Syndrome Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Single-Word Comprehension Impairment | Left Anterior Temporal Lobe (Temporal Pole) | Peak atrophy invariably associated with word comprehension deficits [7] | Semantic Variant PPA |

| Sentence Comprehension Impairment | Heterogeneous Sites: Temporoparietal cortex, Broca's area, dorsal premotor cortex | Inconsistent impairment with temporoparietal damage alone [7] | Agrammatic Variant PPA |

| Relative Preservation of Single-Word Comprehension | Classical Wernicke's Area (pSTG/SMG) | Damage leaves single-word comprehension intact [7] [8] | Conduction Aphasia, Logopenic PPA |

Revised Model of Posterior Language Function

Contemporary evidence indicates the anatomically-defined Wernicke's area (pSTG/SMG) is critical for phonologic retrieval in speech production rather than comprehension [8]. This region acts as a repository for phoneme sequences needed for word production, with damage causing phonemic paraphasias (characteristic of conduction aphasia and Wernicke's aphasia) without necessarily impairing comprehension [8]. Functional MRI and lesion studies show word comprehension involves a distributed network including middle temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, and anterior temporal lobe, while sentence comprehension requires integration across temporoparietal and frontal regions [7] [8].

Figure 2: Revised Language Network Model: This diagram illustrates the dissociated functions within the posterior language network. The classical Wernicke's area (pSTG/SMG) is primarily engaged in phonologic retrieval for speech production. Comprehension involves distinct pathways connecting auditory perception to distributed semantic systems, explaining why Wernicke's area damage impairs production but not necessarily comprehension.

H.M.: The Medial Temporal Lobe and Memory Systems

Case History and Experimental Paradigm

In 1953, patient Henry Molaison (H.M.) underwent bilateral medial temporal lobe resection to treat intractable epilepsy, resulting in profound anterograde amnesia [9] [10] [11]. Despite preserved intellectual function, personality, and immediate memory, H.M. could not form new long-term declarative memories while retaining some capacity for procedural learning [10] [11]. This case provided the first conclusive evidence for medial temporal lobe (especially hippocampal) involvement in memory consolidation and revealed the fundamental distinction between different memory systems [11].

Quantitative Postmortem Analysis Protocol

Postmortem examination of H.M.'s brain provided precise anatomical verification of his lesions:

- Brain Fixation and Sectioning: Whole-brain fixation followed by serial sectioning in coronal plane (70μm thickness) aligned with anterior-posterior commissure plane [9].

- Digital Imaging and 3D Reconstruction: Acquisition of 2,401 high-resolution digital images of block surface with histological staining of sections for 3D volumetric reconstruction [9].

- Anatomical Measurement: 3D measurement tools used to calculate lesion extent and spared hippocampal tissue volume [9].

- Cytoarchitectonic Analysis: Microscopic examination of stained sections to identify residual hippocampal tissue based on distinctive cellular architecture [9].

Table 3: Quantitative Postmortem Measurements of H.M.'s Medial Temporal Lobe Lesions

| Brain Structure | Left Hemisphere Measurement | Right Hemisphere Measurement | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Length (anterior-posterior) | 54.5 mm | 44.0 mm | Asymmetry may explain variable retrograde amnesia |

| Residual Entorhinal Cortex Volume | 0.03 cm³ | 0.11 cm³ | Near-complete removal disrupted hippocampal input |

| Residual Hippocampal Formation | Significant portion spared posteriorly | Significant portion spared posteriorly | Spared tissue was functionally disconnected |

| Key Structures Removed | Amygdala, entorhinal cortex, anterior hippocampus | Amygdala, entorhinal cortex, anterior hippocampus | Necessary for declarative memory formation |

Behavioral Testing and Memory Dissociations

Systematic neuropsychological testing revealed dissociations in H.M.'s memory capabilities:

- Declarative Memory Tasks: Impaired recall and recognition of facts, events, and personal experiences (episodic and semantic memory) [10] [11].

- Procedural Learning Tasks: Preserved motor skill learning (mirror tracing), perceptual learning, and classical conditioning despite no conscious memory of training sessions [10] [11].

- Perceptual Identification Tests: Demonstrated intact repetition priming effects (facilitated processing of previously encountered stimuli) [10].

These findings established the critical distinction between declarative memory (dependent on medial temporal lobe structures) and nondeclarative memory (supported by other neural systems) [10].

Figure 3: H.M.'s Memory Dissociations: This model illustrates how H.M.'s medial temporal lobe (MTL) resection disrupted the consolidation of declarative memories while sparing nondeclarative memory systems. The MTL is necessary for transferring information from immediate experience to stable long-term storage in neocortical regions but is not required for procedural learning or priming effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Lesion-Behavior Correlation Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Structural MRI (T1-weighted) | Precise anatomical visualization and lesion demarcation | Quantifying lesion volume and location in stroke patients [4] |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) | Reconstruction of white matter pathways and disconnection analysis | Identifying involvement of arcuate fasciculus in conduction aphasia [5] |

| Perfusion-Weighted MRI (PASL) | Measurement of cerebral blood flow to identify dysfunctional tissue | Detecting hypoperfusion in Broca's area with insular lesions [4] |

| Voxel-Based Morphometry Software | Automated quantification of cortical atrophy or lesion distribution | Correlating peak atrophy sites with comprehension deficits in PPA [7] |

| Direct Electrical Stimulation (DES) | Transient, reversible functional interference during awake surgery | Mapping critical language sites by inducing speech arrest [6] |

| Standardized Neuropsychological Batteries | Comprehensive assessment of specific cognitive domains | Western Aphasia Battery for language; specific tests for declarative vs. procedural memory [7] [11] |

| Cytoarchitectonic Atlas | Microscopically-defined cortical area boundaries for precise localization | Defining Brodmann areas 44/45 beyond macroscopic landmarks [5] |

The seminal case studies of Broca's aphasic patients, Wernicke's aphasic patients, and patient H.M. established foundational principles that continue to guide cognitive neuroscience. These cases demonstrated the value of the lesion method for making causal inferences about brain-behavior relationships, revealed the functional specialization of distinct brain regions and networks, and illustrated the dissociability of cognitive processes. Modern neuroimaging techniques and analysis methods have refined our understanding of these classical cases, leading to more precise anatomical correlations and sophisticated network models. The continuing evolution of lesion-behavior research provides critical insights for diagnosing and treating neurological disorders, developing targeted cognitive interventions, and informing drug development strategies aimed at specific neural circuits. These historical foundations remind us that careful observation of individual patients, combined with innovative methodological approaches, continues to drive discovery in cognitive neuroscience.

Application Notes: Core Principles of the Lesion Method

The lesion method is a foundational scientific approach in neuroscience for correlating brain structure with function. Its underlying logic is based on a subtractive principle: by studying the behavioral capacities that are lost following damage to a specific brain region, researchers can infer the necessary function of that area [1]. If a lesion in brain area X leads to a deficit in behavior Y, it suggests that area X is necessary for the normal execution of behavior Y [12]. This method has been instrumental for over 200 years in mapping cognitive functions like language, memory, and emotion to specific neural substrates [1].

Modern applications of the lesion method have evolved from single-case studies to group lesion studies, which analyze cohorts of patients with similar brain injuries. This allows scientists to determine if lesions to certain brain areas consistently produce the same behavioral changes across different individuals, strengthening conclusions about necessity [1]. Furthermore, the integration of the lesion method with neuroimaging techniques and standardized data management tools like the Neuroscience Experiments System (NES) allows for more sophisticated analysis of how interconnected brain networks support behavior [1] [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Single-Case Study Behavioral Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for conducting a deep behavioral analysis of a single patient with a focal brain lesion, following the models of historic cases like patient H.M. or patient S.M. [1].

- Objective: To establish a causal link between a specific brain area and a defined cognitive or behavioral function through in-depth analysis of a single patient.

- Materials: Neuropsychological assessment batteries, video recording equipment, standardized stimulus sets, the Neuroscience Experiments System (NES) or similar data management software for collecting behavioral and participant data [13].

- Procedure:

- Patient Characterization: Record detailed medical, demographic, and neuropsychological history. Obtain informed consent.

- Lesion Mapping: Acquire high-resolution structural neuroimages (e.g., MRI or CT). Precisely reconstruct the lesion location onto a standardized brain template using appropriate software.

- Baseline Behavioral Assessment: Administer a comprehensive battery of standardized tests to establish a profile of preserved and impaired functions across multiple domains (e.g., memory, language, executive function).

- Targeted Experimental Testing: Based on the initial assessment, design and administer customized experiments to probe the specific function linked to the lesioned area. Examples include:

- Fear Induction: For amygdala lesions, expose the patient to fear-inducing stimuli (live snakes, spiders, haunted houses) and measure subjective fear reports, physiological responses, and behavioral avoidance [1].

- Memory Tasks: For medial temporal lobe lesions, test recall and recognition of new information after varying delay intervals.

- Data Integration and Analysis: Correlate the precise anatomical location of the lesion with the specific behavioral deficit. The conclusion of necessity is supported if the patient cannot perform a function they had prior to the injury, and that deficit is consistently linked to the lesioned area.

Protocol for Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM)

This protocol describes a group-study approach that uses modern brain imaging and statistics to correlate lesion location with behavioral performance on a voxel-by-voxel basis [12].

- Objective: To systematically identify brain regions where tissue damage is significantly associated with deficits in a specific behavioral task across a large cohort of brain-injured patients.

- Materials: Access to a cohort of patients with focal brain lesions (e.g., stroke), standardized behavioral task, high-resolution structural MRI or CT scans, computing software capable of running VLSM analysis (e.g., MRIcron, NiiStat).

- Procedure:

- Participant Selection and Recruitment: Recruit a well-characterized cohort of patients with chronic, stable focal brain lesions, typically from stroke.

- Behavioral Testing: Administer the same standardized behavioral task to all participants. The Curtiss-Yamada Comprehensive Language Evaluation (CYCLE-R) is an example used for language comprehension [12].

- Neuroimaging and Lesion Reconstruction: Obtain structural brain scans for each participant. Manually or semi-automatically trace each patient's lesion onto a standardized brain template.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize all lesion maps to a common stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI).

- Statistical Analysis (VLSM): For each voxel in the brain, the analysis compares the behavioral scores of two patient groups: those with a lesion at that voxel and those without. A statistical test (e.g., t-test) is performed at every voxel to identify locations where damage significantly impairs performance.

- Multiple Comparisons Correction: Apply statistical correction (e.g., False Discovery Rate) to the resulting map to control for false positives arising from testing thousands of voxels.

- Interpretation: Brain regions that survive correction are interpreted as being critically necessary for the behavior in question.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Foundational single-case studies established the logic of subtractive analysis for inferring necessity [1].

| Patient (Year) | Brain Area Lesioned | Behavioral Deficit | Inferred Necessity of Brain Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phineas Gage (1848) | Frontal Lobe | Profound personality change; impaired planning and social conduct | Frontal lobe is necessary for personality, planning, and social behavior |

| Louis Leborgne (1861) | Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus (Broca's area) | Severely impaired speech production; could comprehend language | Broca's area is necessary for fluent speech production |

| Susanne Adam (1874) | Left Posterior Temporal Lobe (Wernicke's area) | Impaired language comprehension; fluent but nonsensical speech | Wernicke's area is necessary for understanding language |

| Henry Molaison (1953) | Bilateral Medial Temporal Lobe (Hippocampus) | Profound anterograde amnesia; inability to form new memories | Hippocampus is necessary for the formation of new long-term memories |

| S.M. (1990s) | Bilateral Amygdala | Complete absence of fear response | Amygdala is necessary for experiencing fear |

Key Brain Areas Implicated in Language Comprehension by Group Lesion Studies

Table 2: Modern group studies using VLSM have identified a network of brain areas necessary for language comprehension, moving beyond classic models [12].

| Brain Area | Key Function in Comprehension (from VLSM) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Posterior Middle Temporal Gyrus | Word-level comprehension | Critical for accessing lexical-semantic information |

| Anterior Superior Temporal Gyrus | Sentence-level comprehension | Involved in early stages of syntactic and auditory processing |

| Superior Temporal Sulcus & Angular Gyrus | Sentence-level comprehension | Supports integration of semantic and syntactic information |

| Mid-Frontal Cortex (Brodmann Area 46) | Sentence-level comprehension | Important for working memory demands during comprehension |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus (Brodmann Area 47) | Sentence-level comprehension | Involved in semantic processing and selection |

Visualization of Methodologies

The Logic of the Lesion Method

Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for conducting modern lesion method studies.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Lesion Studies |

|---|---|

| Structural MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) | Provides high-resolution, 3D anatomical images of the brain for precise localization and reconstruction of lesions. |

| Standardized Neuropsychological Batteries | Assess a wide range of cognitive functions (memory, language, attention) to create a detailed profile of behavioral deficits and preserved abilities. |

| Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) Software | Enables statistical analysis of the relationship between lesion location and behavioral scores on a voxel-by-voxel basis across a patient group [12]. |

| Neuroscience Experiments System (NES) | An open-source software tool that assists researchers in managing experimental data, protocols, and participant information, ensuring standardized data collection and provenance [13]. |

| Standardized Brain Atlases (e.g., MNI space) | Provide a common coordinate system for mapping individual patient lesions, allowing for group comparisons and meta-analyses. |

The lesion method, one of the oldest approaches in behavioral neuroscience, remains foundational for correlating brain structure with function. This methodology examines behavioral and cognitive changes resulting from focal brain damage to infer the functional roles of specific neural regions. Historically, studies of patients with accidental brain injuries provided groundbreaking insights into brain organization, while modern research employs more precise, experimentally controlled lesions in animal models. This article details key discoveries in localizing memory, language, and executive functions, providing application notes and experimental protocols for researchers investigating brain-behavior relationships. The principles outlined serve both basic neuroscience research and drug development efforts aimed at treating neurological and psychiatric disorders affecting these cognitive domains.

Memory Systems Localization

Key Discoveries and Anatomical Substrates

Research using the lesion method has revealed that memory is not a unitary faculty but consists of multiple dissociable systems dependent on distinct brain regions. The critical distinction between explicit (declarative) and implicit (non-declarative) memory has been clearly demonstrated through lesion studies.

Table 1: Memory Systems and Their Neural Substrates

| Memory System | Brain Substrates | Primary Functions | Key Lesion Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit/Declarative Memory | Hippocampus, medial temporal lobe | Conscious recall of facts and events | Anterograde amnesia following medial temporal lobe lesions [14] |

| Implicit/Non-declarative Memory | Cerebellum, amygdala | Unconscious learning of skills and associations | Preserved implicit learning in amnesic patients with hippocampal damage [14] |

| Classical Conditioning (Delay) | Cerebellum | Learning of overlapping stimulus-response associations | Cerebellar lesions impair basic delay conditioning [14] |

| Trace Conditioning | Hippocampus | Learning with temporal gap between stimuli | Hippocampal lesions impair trace conditioning [14] |

The seminal case of patient H.M., who underwent bilateral medial temporal lobe resection, demonstrated that the hippocampus is critical for forming new explicit memories while leaving implicit memory systems largely intact [14]. Subsequent lesion studies further refined this model, revealing that other medial temporal lobe structures, including the perirhinal, parahippocampal, and entorhinal cortices, also contribute to declarative memory, with more profound amnesia resulting from larger lesions encompassing these areas [14].

Experimental Protocol: Trace Conditioning Paradigm

Purpose: To assess hippocampal-dependent memory in animal models using trace conditioning.

Materials:

- Animal subjects (e.g., rabbits, rodents)

- Classical conditioning apparatus with stimulus delivery systems

- Response measurement system (e.g., eyelid detector, limb flexion sensor)

- Surgical equipment for stereotaxic lesions (if creating experimental lesions)

- Histological materials for lesion verification

Procedure:

- Habituation: Expose subjects to the experimental context without stimuli.

- Pre-training Baseline: Measure baseline responses to conditioned stimulus (CS) and unconditioned stimulus (US).

- Lesion Induction (if applicable): Create bilateral hippocampal lesions using:

- Aspiration lesions: Surgical removal of hippocampal tissue

- Neurotoxic lesions: Microinjections of excitotoxins (e.g., ibotenic acid) for selective cell body destruction

- Electrolytic lesions: Electrical current to create targeted damage

- Recovery: Allow 1-2 weeks post-surgical recovery.

- Training:

- Trace Conditioning Group: Present CS (e.g., tone) for 250ms, followed by a 500ms trace interval with no stimuli, then US (e.g., corneal airpuff) for 100ms.

- Delay Conditioning Control: Present CS and US with temporal overlap.

- Testing: Assess conditioned response (CR) acquisition across multiple sessions.

- Lesion Verification: Perfuse, section, and stain brain tissue to verify lesion location and extent.

Applications: This protocol effectively differentiates hippocampal-dependent from hippocampal-independent learning. The temporal characteristics of hippocampal involvement can be examined by varying the interval between training and lesion induction [14].

Visualization: Memory Systems and Hippocampal Dependency in Trace Conditioning

Figure 1: Organization of memory systems showing distinct neural substrates for explicit and implicit memory, with specialized hippocampal involvement in trace conditioning.

Language Localization

Historical Foundations and Contemporary Models

The lesion method has been instrumental in identifying brain regions essential for language processing since Paul Broca's seminal work in the 19th century. The case of Broca's patient Lebornge established the critical role of the left inferior frontal gyrus in speech production, while Carl Wernicke's later studies revealed the importance of the left posterior superior temporal gyrus in language comprehension [15].

Henry Charlton Bastian's detailed documentation of patient Thomas A. over 18 years represented a landmark in clinico-pathological correlation methods for language localization [15]. Bastian's work pioneered systematic assessment across language modalities (speech, writing, reading, and listening), establishing a foundation for contemporary language mapping.

Table 2: Language Areas Identified Through Lesion Studies

| Brain Region | Function | Deficit from Lesion | Laterality Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broca's Area (left inferior frontal gyrus) | Speech production, language processing | Non-fluent aphasia, effortful speech | Strongly left-lateralized [16] |

| Wernicke's Area (left posterior superior temporal gyrus) | Speech comprehension, semantic processing | Fluent but meaningless speech, impaired comprehension | Strongly left-lateralized [16] |

| Arcuate Fasciculus | Connecting Broca's and Wernicke's areas | Conduction aphasia (impaired repetition) | Left-lateralized [15] |

| Supramarginal and Angular Gyri | Reading, writing, integration of sensory information | Alexia, agraphia, conduction aphasia | Variable lateralization [16] |

Contemporary models suggest differentiated lateralization patterns for distinct language processes. According to the dual-stream model of speech processing, while speech comprehension and semantic processing are typically left-lateralized, basic acoustic processing of speech input and speech articulation involve bilateral networks [16].

Experimental Protocol: Language Lateralization Assessment

Purpose: To determine hemispheric dominance for language using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with language tasks.

Materials:

- MRI scanner (3T or higher recommended)

- Presentation software for stimulus delivery

- Response recording devices (fMRI-compatible button boxes)

- Eye-tracking equipment (optional, for monitoring attention)

- Analysis software (e.g., SPM, FSL, AFNI)

Procedure:

- Subject Screening: Recruit right-handed, monolingual adults with no neurological history.

- Task Selection: Choose language tasks targeting specific processes:

- Verbal Fluency: Generate words beginning with a specific letter

- Semantic Decision: Judge category membership of presented words

- Sentence Comprehension: Process complex syntactic structures

- Object Naming: Name pictures of objects

- Baseline Tasks: Design matched control tasks (e.g., tone discrimination for auditory tasks, visual fixation for visual tasks).

- fMRI Acquisition:

- Collect high-resolution structural images (T1-weighted)

- Acquire functional images (T2*-weighted EPI) during task performance

- Use standard parameters: TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, voxel size=3×3×3mm

- Data Analysis:

- Preprocess data (realignment, normalization, smoothing)

- Model hemodynamic response to task conditions

- Calculate Laterality Index (LI) using the formula: LI = (L - R)/(L + R)

- Define regions of interest (ROIs), particularly in inferior frontal and temporal regions

- Interpretation: LI > +0.2 indicates left lateralization; LI < -0.2 indicates right lateralization; intermediate values indicate bilateral representation.

Applications: This protocol is valuable for presurgical mapping in epilepsy and tumor patients, as well as for research on individual differences in language organization [16].

Executive Functions Localization

From Frontal Lobes to Distributed Networks

Executive functions (EFs) represent higher-level cognitive processes that control and coordinate goal-directed behavior, including working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, and planning. Early lesion studies, most famously the case of Phineas Gage, highlighted the importance of the frontal lobes for executive control [17]. However, contemporary research reveals that EFs are supported by distributed thalamocortical networks rather than isolated frontal regions.

Table 3: Executive Functions and Their Neural Substrates

| Executive Function | Key Brain Regions | Associated Lesion Deficits | Assessment Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Updating | Middle frontal gyrus (BA 8), supramarginal gyrus | Impaired monitoring of working memory contents | n-back tasks [18] |

| Inhibition | Inferior frontal gyrus (BA 46), mediodorsal thalamus | Deficits in suppressing prepotent responses | Stroop test, stop-signal task [18] |

| Switching | Superior frontal gyrus (BA 8), inferior parietal lobule | Perseveration, difficulty shifting task sets | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, task-switching paradigms [18] |

| Dual-tasking | Postcentral gyrus (BA 40), frontoparietal network | Impaired simultaneous task performance | Psychological Refractory Period paradigm [18] |

A meta-analytic review of lesion studies indicates that the relationship between executive functions and the frontal lobes is more complex than initially proposed. While frontal damage often disrupts EFs, the correlation is not one-to-one, with some frontal lesions sparing certain EFs and some non-frontal lesions impairing them [19].

Experimental Protocol: Mediodorsal Thalamus Lesion and Executive Function Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate the role of the mediodorsal thalamus in executive functions using focal lesions and neuropsychological testing.

Materials:

- Human patients with focal thalamic lesions or animal subjects

- MRI/CT scanner for lesion localization

- Neuropsychological assessment tools

- Stereotaxic apparatus (for animal studies)

- Lesion mapping software

Procedure:

- Participant Selection:

- Identify patients with focal thalamic lesions (e.g., from stroke)

- Recruit matched control patients with non-thalamic lesions

- Confirm lesion location with structural neuroimaging

- Lesion Analysis (for animal studies):

- Induce focal mediodorsal thalamic lesions using stereotaxic surgery

- Use coordinate-based approach with neurotoxins for selective damage

- Include sham-operated controls

- Executive Function Assessment:

- Trail Making Test (TMT): Assess cognitive flexibility (TMT-B)

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST): Evaluate abstraction and set-shifting

- Verbal Fluency Tests: Measure generative capacity and strategic search

- Stroop Color-Word Test: Assess inhibitory control

- Lesion Network Mapping:

- Use normative functional connectivity data

- Map networks functionally connected to lesion locations

- Identify connected cortical regions potentially affected by thalamic lesions

- Data Analysis:

- Compare executive function performance between mediodorsal thalamic lesion patients, other thalamic lesion patients, and controls

- Corregate lesion location with specific EF deficits

- Analyze functional connectivity profiles of lesion sites

Applications: This protocol helps elucidate the role of thalamocortical circuits in executive control, with implications for understanding cognitive deficits in disorders such as vascular dementia, traumatic brain injury, and Parkinson's disease [20].

Visualization: Unity and Diversity of Executive Function Networks

Figure 2: Neural correlates of executive functions showing both unity (shared frontoparietal regions) and diversity (unique regions for specific functions).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Lesion Method Research

| Research Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ibotenic Acid | Excitotoxic lesion agent; selectively destroys cell bodies while sparing fibers of passage | Creating selective hippocampal or thalamic lesions in animal models [17] |

| Kainic Acid | Neurotoxin targeting glutamate receptors; induces selective neuronal death | Modeling temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal damage [17] |

| 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) | Catecholaminergic neurotoxin; selectively destroys dopamine and norepinephrine neurons | Creating Parkinson's disease models with nigrostriatal pathway lesions [17] |

| MRI Contrast Agents (Gadolinium) | Enhances visualization of brain structures and lesions in magnetic resonance imaging | Precise localization of lesion extent in human and animal studies [21] |

| Functional Localizer Tasks | Standardized cognitive tasks designed to activate specific brain networks | Language lateralization fMRI protocols; executive function localization [22] [16] |

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Precise positioning system for targeted brain interventions | Accurate lesion placement in specific nuclei or cortical regions in animal studies [17] |

The lesion method continues to provide fundamental insights into brain-behavior relationships, with modern approaches combining precise lesion localization with advanced neuroimaging and connectivity analyses. The discoveries summarized here—regarding the distributed networks supporting memory, language, and executive functions—highlight both the specialization and integration of neural systems. For researchers in both academic and pharmaceutical development contexts, these findings and protocols offer valuable approaches for investigating brain function and developing interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Future directions will likely include more sophisticated temporary lesion techniques, such as optogenetics and transcranial magnetic stimulation, which allow reversible manipulation of neural circuits with temporal precision, building upon the foundational knowledge established through permanent lesion studies.

Application Notes: Advancing from Focal Lesions to Network-Level Mapping

The field of lesion mapping has undergone a paradigm shift, moving from correlating symptoms with single brain regions to mapping them onto distributed brain networks. This modern approach recognizes that lesions in disparate anatomical locations can cause identical symptoms by disrupting a common functional brain circuit [23] [24]. Lesion network mapping (LNM) has successfully identified network correlates for over 40 different neurological and psychiatric symptoms, including complex conditions like hallucinations, tics, and criminality that were previously difficult to localize [23]. This network perspective provides a more complete pathophysiological model for symptoms that defy simple anatomical explanation.

Key Quantitative Benchmarks in Modern Lesion Mapping

The following table summarizes performance data and key parameters from contemporary lesion-symptom mapping studies, highlighting the integration of machine learning and multimodal neuroimaging.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Modern Lesion-Symptom Mapping Techniques

| Study Focus / Model | Behavioral Measure | Key Imaging Features | Performance (Correlation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Benchmarking (Random Forest) [25] | Aphasia Quotient (AQ) | Lesion location (JHU atlas) | Moderate to High Correlation |

| Machine Learning Benchmarking (Random Forest) [25] | Philadelphia Naming Test (PNT) | Lesion location (JHU atlas) | Moderate to High Correlation |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) Multimodal [25] | Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT) | Lesion Volumes | r = 0.59 |

| SVR-MLSM [25] | WAB-R Aphasia Quotient (AQ) | Multimodal Neuroimaging | r = 0.69 |

| Multimodal ML for Post-stroke Aphasia [25] | Phonology, Semantics, Fluency, Executive Demand | Structural T1 & DTI features | r = 0.50 to 0.73 |

Successful implementation of modern lesion mapping protocols relies on several key software and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Lesion Network Mapping

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lead-DBS Software [24] | Software Toolbox | Facilitates lesion network mapping and deep brain stimulation (DBS) network mapping within a standardized framework. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data [23] [24] | Reference Dataset | Provides a large-scale atlas of normative human brain connectivity (the connectome) derived from resting-state fMRI, essential for calculating functional connectivity of lesion locations. |

| JHU MRI Atlas [25] | Brain Parcellation Atlas | A commonly used brain atlas for defining regions of interest (ROIs); identified as providing high performance in ML models for predicting language outcomes. |

| AAL, BRO, AICHA Atlases [25] | Brain Parcellation Atlases | Alternative brain atlases used for parcellating neuroimaging data and extracting features for model training. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM)

Application Note: This univariate technique is used for initial, voxel-level identification of brain regions where lesion presence is significantly associated with a behavioral deficit [25] [23]. It is most effective for localizing elementary neurological deficits.

Workflow:

- Data Preparation:

- Input: T1-weighted structural MRI scans from a cohort of patients with focal brain lesions.

- Lesion Segmentation: Manually trace or automatically segment lesions on each patient's MRI. Normalize all lesion maps to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI).

- Behavioral Data: Collect quantitative behavioral scores for all patients (e.g., Aphasia Quotient, naming test scores).

- Statistical Analysis:

- For each voxel in the brain, perform a statistical test (e.g., t-test, non-parametric Brunner-Munzel test) to compare behavioral scores between patients with and without a lesion at that voxel [25] [23].

- Correct for multiple comparisons across voxels using family-wise error (FWE) correction or false discovery rate (FDR).

- Output: A statistical map highlighting voxels where lesion presence significantly predicts behavioral impairment.

Protocol: Lesion Network Mapping (LNM)

Application Note: This multivariate technique maps lesion locations to brain-wide networks, revealing circuit-level correlates of symptoms, especially when lesions are anatomically heterogeneous [23] [24]. It is ideal for complex neurological or psychiatric symptoms.

Workflow:

- Define Lesion Locations:

- Input: A set of lesion masks from patients presenting with a specific symptom of interest (e.g., hallucinations).

- Control Group: A set of lesion masks from patients not presenting with the symptom.

- Generate Functional Connectivity Maps:

- For each lesion mask, use a normative connectome (e.g., from the HCP) to identify all brain regions that are functionally connected to the lesion location [23] [24]. This is done by extracting the average resting-state fMRI time series from the lesion ROI in healthy controls and correlating it with every other voxel in the brain.

- Statistical Comparison:

- Compare the connectivity maps of the symptom-positive lesions against the symptom-negative (control) lesions. Voxels showing significantly stronger connectivity to the symptom-positive lesions constitute the "symptom network" [23].

- Output: A brain-wide map identifying the network functionally connected to lesions causing a specific symptom.

Protocol: Machine Learning for Outcome Prediction

Application Note: This protocol uses machine learning (ML) models to predict continuous behavioral outcomes (e.g., language test scores) from multimodal neuroimaging data, capturing complex, non-linear relationships beyond traditional mass-univariate methods [25].

Workflow:

- Feature Extraction:

- Input: Multimodal neuroimaging data (e.g., T1, DTI, resting-state fMRI).

- Parcellation: Parcellate the brain using a defined atlas (e.g., JHU, AAL).

- Feature Calculation: From each region, extract features such as lesion presence, fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), and functional connectivity (FC) strength [25].

- Model Training with Nested Cross-Validation:

- Outer Loop: Splits data into training and test sets for performance estimation.

- Inner Loop: On the training set, perform cross-validation to tune model hyperparameters.

- Algorithms: Train and compare multiple ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, Gradient Boosting) [25].

- Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set to obtain a unbiased performance metric (e.g., Pearson's correlation).

- Output: A trained model capable of predicting behavioral scores from new patient imaging data, along with identification of features most critical for prediction.

Modern Lesion Analysis Techniques: From Voxel-Based Mapping to Clinical Translation

Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping (VLSM) is a statistical neuroimaging technique used to correlate brain lesion locations with behavioral deficits in neurological patients. This method represents a significant advancement over traditional lesion overlay approaches, allowing for a voxel-by-voxel analysis of the relationship between brain damage and cognitive, sensory, or motor impairments without requiring a priori hypotheses about lesion location [26]. First introduced by Bates and colleagues in 2003, VLSM has since become a cornerstone technique in the field of lesion-behavior mapping, enabling researchers to identify brain regions critical for specific functions by analyzing naturally occurring lesion patterns in patient populations, most commonly stroke survivors [26] [27].

The fundamental principle underlying VLSM is that if damage to a particular brain voxel consistently leads to impairment on a specific behavioral measure, that voxel can be inferred to be critically involved in the cognitive or neural processes supporting that behavior. Unlike earlier methods that required dichotomizing patients into groups based on either lesion location or behavioral deficit, VLSM leverages the continuous nature of both lesion data and behavioral scores, increasing statistical power and spatial precision [26]. This technique has been successfully applied to study various neurological conditions including stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and surgical resections, contributing significantly to our understanding of brain-behavior relationships [26].

Core Principles of VLSM

Theoretical Foundations

VLSM operates on the fundamental assumption that if a specific brain region is necessary for a given cognitive function, then damage to that region should result in impairment of that function. This lesion-deficit approach has roots in 19th century neurology, with pioneers such as Broca, Wernicke, and Dax using autopsy data to correlate brain damage with behavioral symptoms [26]. The modern VLSM approach was inspired by univariate analysis methods used in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), adapted to leverage the natural experiments provided by brain lesions [26].

A key advantage of VLSM over traditional lesion methods is its ability to analyze continuous behavioral data without requiring arbitrary patient groupings based on syndrome classifications or cutoff scores [26]. This preserves the full richness and variability of both the neuroanatomical and behavioral data. Additionally, VLSM does not require dividing patients based on lesion location, which is particularly advantageous given that naturally occurring lesions rarely respect neat anatomical boundaries [26].

Statistical Framework

VLSM employs mass univariate testing, performing an independent statistical test at every voxel in the brain to determine whether damage to that voxel is associated with worse performance on a behavioral measure [26]. The core statistical approach involves comparing behavioral scores between patients with and without damage at each voxel, typically using one-tailed tests with the assumption that lesioned voxels are associated with worse performance [26].

Table 1: Common Statistical Tests Used in VLSM Analysis

| Test Type | Data Type | Key Characteristics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | Continuous | Parametric test; assumes normality and equal variances | Sensitive to violations of assumptions; commonly used |

| Brunner-Munzel Test | Continuous | Non-parametric; fewer assumptions than t-test | More robust when parametric assumptions are violated |

| Chi-square Test | Binomial/Categorical | Tests association between lesion status and binary outcome | Requires categorical behavioral data |

| Liebermeister Test | Binomial/Categorical | Non-parametric alternative to chi-square | More appropriate for binomial data with small sample sizes |

| Regression | Continuous | Can handle continuous lesion data (0-1) | Allows for more nuanced modeling of lesion extent |

The VLSM framework must account for multiple statistical comparisons across thousands of voxels. Family-wise error correction is typically employed to control the probability of false positives, with rigorous correction methods being a current best practice [26]. Additional considerations include covarying for potentially confounding variables such as total lesion volume and ensuring sufficient statistical power by limiting interpretation to brain regions with adequate lesion coverage [26].

VLSM Workflow

The VLSM workflow involves a series of methodical steps from data acquisition through statistical analysis and result interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the complete process:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The initial phase involves collecting high-quality neuroimaging and behavioral data from patients with focal brain lesions. Structural MRI sequences (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR) are typically acquired to visualize lesion boundaries clearly [26]. While chronic stroke patients when lesion boundaries are most stable are most commonly studied, VLSM has also been applied to acute stroke patients using diffusion-weighted imaging, providing insights into brain-behavior relationships prior to significant neural reorganization [26].

Behavioral assessment should be comprehensive and targeted to the cognitive domains of interest. For language mapping, standardized tests such as the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R) Aphasia Quotient or Philadelphia Naming Test (PNT) are commonly used [25]. For visual scene memory, assessments like the WMS-III Family Pictures subtest can evaluate memory for different scene elements including identity, location, and action [28]. Behavioral testing should ideally occur close in time to neuroimaging acquisition.

Lesion delineation involves manually or semi-automatically tracing lesion boundaries on each patient's native brain images to create binary lesion masks. This process requires neuroanatomical expertise and should be performed by raters blinded to behavioral data when possible. For chronic strokes, lesion boundaries are typically clear once residual edema and bleeding have resolved [26].

Spatial Normalization

A critical step in VLSM is spatial normalization, where individual patient brains are transformed into a standard coordinate space, typically the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template [26]. This allows for comparison and statistical analysis across patients despite natural anatomical variability. Both the lesion masks and native brain images are transformed using linear or non-linear registration algorithms, with careful quality control to ensure proper alignment.

Normalized lesion masks are resampled to a common resolution and stored as binary images where each voxel indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of lesion. Some VLSM implementations can also handle continuous lesion data ranging from 0 to 1 to represent partial volume effects or degree of damage [26]. The resulting collection of lesion masks forms the primary neuroanatomical dataset for subsequent analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The core VLSM analysis involves performing voxel-wise statistical tests comparing behavioral scores between patients with and without damage at each voxel. For continuous behavioral data, t-tests or Brunner-Munzel tests are commonly employed, while binomial or categorical data may use chi-square or Liebermeister tests [26]. The analysis is typically restricted to voxels that are damaged in a sufficient number of patients (often 5 or more) to ensure adequate statistical power [26] [29].

Multiple comparison correction is essential due to the thousands of statistical tests performed. Family-wise error rate (FWER) control through permutation testing or false discovery rate (FDR) correction are standard approaches [26]. Covariates such as total lesion volume, age, or time post-onset can be included in the model to control for potential confounds.

Table 2: Key Considerations in VLSM Statistical Analysis

| Analysis Aspect | Options | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Test | T-test, Brunner-Munzel, Chi-square, Liebermeister | Choose based on data type and distribution; non-parametric tests often more robust |

| Multiple Comparison Correction | Family-wise Error Rate (FWER), False Discovery Rate (FDR) | FWER more conservative but controls false positives; minimum cluster extent can supplement |

| Covariates | Lesion volume, age, education, time post-onset | Always covary for lesion volume; consider other clinically relevant factors |

| Threshold Criteria | Maximum voxel statistic, submaximal clusters, contiguous clusters | Use combination approaches; report exact thresholds and correction methods |

| Statistical Power | Minimum number of lesioned voxels, effect size considerations | Limit interpretation to voxels with sufficient lesion coverage (≥5 patients) |

Result Interpretation

Significant results from VLSM analysis are typically visualized as statistical maps overlaid on template brains, with color scales representing the strength of association between lesion location and behavioral deficit [26]. These maps can be viewed using software such as ITK-SNAP or MRIcron, with reference to standardized atlases (e.g., AAL, Harvard-Oxford, JHU white matter) for anatomical localization [26].

Interpretation should consider the network nature of brain function, as lesions to critical white matter pathways can produce deficits by disconnecting brain regions even when cortical areas are spared. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of considering both focal damage and network disconnection in lesion-symptom mapping [25]. Additionally, the presence of multicollinearity between lesion locations (where damage to one region frequently co-occurs with damage to another) can complicate interpretation, potentially requiring multivariate approaches like Bayesian network analysis to disentangle true critical regions from epiphenomenal associations [29].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Multivariate Extensions and Machine Learning

While traditional VLSM uses univariate approaches, recent advancements have incorporated multivariate lesion-symptom mapping (MLSM) and machine learning techniques to capture complex relationships between distributed lesion patterns and behavior [25]. These methods can identify patterns of damage across multiple regions that collectively predict behavioral deficits, potentially providing improved predictive accuracy compared to univariate approaches.

Machine learning models including Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, and Gradient Boosting have been applied to lesion-symptom mapping, often incorporating features from multiple neuroimaging modalities such as resting-state functional connectivity, structural connectivity, mean diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy in addition to lesion location [25]. Comparative studies suggest that combining traditional VLSM with multivariate approaches provides the most comprehensive understanding of brain-behavior relationships [25].

Limitations and Validation Studies

Despite its utility, VLSM has several important limitations. Conventional VLSM analyses can be susceptible to Type I errors due to combined effects of multicollinearity and lesion frequency, potentially identifying spurious associations [29]. Validation studies have demonstrated that supplementary analyses such as Bayesian network analysis or logistic regression can help control these errors and provide more reliable identification of critical brain regions [29].

The vascular architecture of the brain constrains natural lesion distributions in stroke patients, potentially limiting the brain regions that can be studied. Combining data from different etiologies (e.g., tumor resection, traumatic brain injury) can provide more comprehensive coverage of brain regions [26]. Additionally, VLSM identifies correlations rather than causal relationships, and careful interpretation is needed to distinguish between critical regions for a function versus regions that correlate with damage for other reasons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for VLSM Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Acquisition | Structural MRI (T1, T2, FLAIR), Diffusion-weighted Imaging (DWI) | Visualize lesion anatomy and boundaries; assess white matter integrity |

| Spatial Normalization | MNI Template, SPM, FSL, ANTs | Transform individual brains to standard coordinate space for group analysis |

| Lesion Delineation | ITK-SNAP, MRIcron | Manual or semi-automated creation of binary lesion masks |

| Statistical Analysis | VLSM Software (https://aphasialab.org/vlsm/), R, MATLAB | Perform voxel-wise statistical tests with multiple comparison correction |

| Anatomical Labeling | AAL Atlas, Harvard-Oxford Atlas, JHU White Matter Atlas, Natbrainlab Atlas | Identify anatomical locations of significant voxel clusters |

| Behavioral Assessment | Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), Philadelphia Naming Test (PNT), WMS Family Pictures | Quantify cognitive, language, or memory deficits for correlation with lesion data |

| Visualization | ITK-SNAP, MRIcron, SurfIce | Display statistical maps overlaid on template brains |

Voxel-Based Lesion-Symptom Mapping represents a powerful method for elucidating brain-behavior relationships by leveraging naturally occurring lesion patterns in neurological patients. When implemented with rigorous statistical controls and careful methodological consideration, VLSM can identify brain regions critical for specific cognitive functions with considerable spatial precision. The technique continues to evolve with incorporation of multivariate approaches, machine learning, and multimodal neuroimaging, further enhancing its utility for cognitive neuroscience and clinical neuropsychology. As with any neuroimaging method, appropriate interpretation requires consideration of both the strengths and limitations of the approach, with results ideally converging with evidence from other methodologies such as functional neuroimaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation.

The lesion method, one of the oldest and most established approaches in neuroscience, seeks to understand brain function by studying the behavioral consequences of focal brain damage [30] [1]. For over two centuries, observations of patients with brain lesions have provided foundational insights into the neural basis of complex cognitive processes such as language, memory, and emotion [30]. Historically, this method relied on single-case studies, like the famous patients Phineas Gage, Louis Leborgne (patient "Tan"), and Henry Molaison (H.M.), each of whom dramatically illustrated the relationship between specific brain areas and behavior [1].

In contemporary neuroscience, the field has moved from studying single lesions to sophisticated multivariate lesion-behaviour mapping (LBM) and lesion network mapping (LNM) techniques [31] [24]. These advanced methods leverage large cohorts of individuals with brain lesions, high-resolution neuroimaging, and normative connectome data to statistically map the neuroanatomical regions and distributed brain networks that are necessary for specific cognitive and motor functions [31] [30]. A key strength of these methods is their ability to demonstrate causal necessity, not merely correlation, between a brain region or network and a given behavior [30].

These techniques address a critical clinical challenge: predicting long-term outcomes after brain injury. It remains difficult to make accurate prognoses due to high inter-individual variability in recovery and a historical reliance on clinical judgment rather than quantitative, empirical methods [31]. Because lesion location can be derived from routinely collected clinical neuroimaging, there is a significant opportunity to use this information to make empirically based predictions about post-stroke deficits [31]. This application note details the protocols and analytical frameworks for implementing these advanced mapping techniques in a research setting.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

From Focal Lesions to Network Dysfunction

Traditional lesion-symptom mapping operates on a fundamental principle: if a lesion in brain region X consistently causes a deficit in function Y, then region X is necessary for function Y [30] [1]. However, a limitation of this focal approach is that symptoms from anatomically disparate lesions can be similar, and lesions in the same location can produce different symptoms, suggesting that a purely focal model is insufficient [24].

Lesion network mapping resolves this paradox by positing that the behavioral effects of a focal lesion are mediated through its impact on a distributed brain network [24]. A lesion not only damages local tissue but also disrupts the function of remote, structurally and functionally connected brain regions [31]. Thus, LNM analyzes the connectivity pattern of brain lesions to identify neuroanatomic correlates of symptoms that cannot be explained by focal anatomic localization alone [24].

Core Methodological Frameworks

Two primary, complementary frameworks form the basis of modern lesion analysis:

Multivariate Lesion-Behaviour Mapping (LBM): This technique uses lesion location and behavioral data from groups of individuals with focal brain damage to produce statistically weighted maps of the neuroanatomical regions that, when damaged, are most strongly associated with specific deficits [31] [32]. It provides a direct link between anatomy and behavior.

Lesion Network Mapping (LNM): This technique uses large, high-quality normative connectome data from healthy individuals to infer the network effects of a focal lesion [31] [24]. The lesion location is used as a seed to identify which functional or structural networks are typically disrupted, thereby linking symptoms to brain networks rather than single points [24]. LNM can be performed using normative functional connectivity (FC) data, which measures correlated brain activity, or structural connectivity (SC) data, which maps white matter tracts [31] [33].

Table 1: Core Concepts in Advanced Lesion Mapping

| Concept | Description | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion-Behaviour Mapping (LBM) | Statistically maps anatomical regions where damage is most associated with a specific deficit [31]. | Identifies brain regions causally necessary for a behavior [30]. |

| Functional Lesion Network Mapping (fLNM) | Maps the lesion's location onto normative resting-state functional connectivity data [31] [24]. | Symptoms arise from disruption of functional brain networks. |

| Structural Lesion Network Mapping (sLNM) | Maps the lesion's location onto normative white matter tractography data [31] [33]. | Symptoms arise from disconnection of structural pathways. |