Theoretical Frameworks for VR in Behavioral Neuroscience: From Embodied Simulation to Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes the key theoretical frameworks underpinning the use of Virtual Reality (VR) in behavioral neuroscience, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Frameworks for VR in Behavioral Neuroscience: From Embodied Simulation to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the key theoretical frameworks underpinning the use of Virtual Reality (VR) in behavioral neuroscience, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principle of 'embodied simulation,' which posits that VR and the brain share a common mechanism for predicting sensory consequences, thereby facilitating cognitive and behavioral change. The scope extends to methodological applications in diagnosing and treating disorders like anxiety, PTSD, and addiction, leveraging VR's capacity for ecologically valid cue exposure. We critically troubleshoot implementation challenges, including methodological limitations and ethical considerations. Finally, we validate the approach through comparative efficacy data and emerging neurobiological evidence of VR-induced neuroplasticity, outlining a future trajectory for personalized, mechanism-driven clinical interventions and drug discovery.

The Brain in the Machine: Foundational Theories of VR and Embodied Cognition

The brain, according to increasingly dominant neuroscience paradigms, is not a passive receiver of stimuli but an active generator of predictions about the world. It maintains an internal model—an embodied simulation—of the body and its surrounding space, which it continuously updates to minimize the discrepancy between predicted and actual sensory input [1]. This process, known as predictive coding, is fundamental to how we perceive, act, and feel [1]. Remarkably, Virtual Reality (VR) technology operates on an analogous principle. A VR system also maintains a real-time simulation of a body and its environment, predicting the sensory consequences of a user's movements and providing corresponding visual and auditory feedback [2] [3]. This shared mechanistic foundation—the creation and manipulation of embodied simulations—is why VR has emerged as such a powerful tool for behavioral neuroscience research and clinical intervention. It provides a unique medium through which researchers can systematically alter the sensory reality presented to the brain, thereby "tricking" its predictive processes to study fundamental mechanisms of cognition and behavior, and ultimately, to promote therapeutic change [2] [1] [3].

This whitepaper explores the unifying framework of embodied simulation, detailing its theoretical underpinnings, its validation through key experimental paradigms, and the practical protocols that enable its application in cutting-edge behavioral neuroscience research.

Theoretical Foundations: Predictive Coding and the Bodily Self

The Predictive Brain

At the core of the embodied simulation framework is the predictive coding theory of brain function [1]. This theory posits that the brain's primary function is to infer the causes of its sensory inputs by constantly generating and refining an internal model of the world and the body within it [1]. This model is not a static representation but a dynamic, multimodal simulation that integrates visceral (interoceptive), motor (proprioceptive), and sensory (e.g., visual, auditory) information [1]. The simulation is used to predict both upcoming sensory events and the optimal actions to deal with them. When there is a mismatch between the brain's prediction and the incoming sensory data—a prediction error—the brain updates its model to improve future predictions [1].

The Body Matrix and Presence

These continuous, multisensory simulations are thought to be integrated within a "body matrix"—a supramodal representation of the body and the peripersonal space around it [1]. This matrix, shaped by top-down predictions and bottom-up sensory signals, is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the body at both homeostatic and psychological levels [1]. It plays a key role in high-level cognitive processes such as motivation, emotion, social cognition, and self-awareness [1].

The psychological sense of "presence"—the feeling of "being there" in a virtual environment—is a direct manifestation of this process [3]. According to the "inner presence" theory, presence is not merely a product of advanced technology but a fundamental cognitive function that identifies which environment (real or virtual) is the most likely to be "real" for the self, based on which one provides the most coherent and least surprising sensory-motor experience for enacting one's intentions [3]. When a VR system provides coherent, multi-sensory feedback that aligns with the brain's own predictions, the user's body matrix begins to incorporate the virtual body and space, leading to a compelling feeling of embodiment and presence within the synthetic world [1] [3].

Experimental Evidence: Validating the Framework

The embodied simulation framework is supported by a growing body of evidence demonstrating VR's efficacy in both eliciting and modifying human experiences in controlled settings. The table below summarizes key findings from clinical and experimental studies.

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence for VR Efficacy Based on Embodied Simulation

| Domain/Disorder | Key Experimental Findings | Implied Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders (Phobias, PTSD) | VR Exposure Therapy (VRET) shows outcomes superior to waitlist controls and comparable to traditional exposure therapy [2]. Effective for specific phobias, PTSD, panic disorder, and social anxiety [2]. | VR safely triggers fear networks; new, corrective learning updates the pathological internal model via prediction error minimization. |

| Eating & Weight Disorders | RCTs show VR-based treatment can have higher efficacy than gold-standard CBT at 1-year follow-up. Effective for anorexia and obesity [2]. | "Body swapping" alters the patient's dysfunctional internal body image simulation, updating the body matrix. |

| Chronic Pain Management | VR embodiment techniques can reduce pain perception and improve body perception disturbance (e.g., in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome) [1]. | VR provides counteractive visual and proprioceptive signals that update the brain's pathological pain and body representation models. |

| Social Skills Acquisition | A single VR training improves job-interview self-efficacy and reduces anxiety, with effects persisting for 4 months. More time-efficient than chat-based training [4]. | VR allows safe embodiment and practice of social interactions, updating the internal model of social self-efficacy and threat. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: VR Body Swapping for Body Image Disturbance

This protocol is adapted from studies on eating and weight disorders, as cited in [2] and [1].

- Objective: To alter the internal body representation (body matrix) in patients with body image disturbance, such as anorexia nervosa or obesity.

- Hypothesis: First-person embodiment in a virtual body with healthier proportions will lead to a measurable behavioral and perceptual shift towards the virtual body, generalizing to the real world.

- Independent Variables: Body type of the virtual avatar (e.g., healthy BMI vs. underweight vs. overweight); Synchrony of visuotactile stimulation (synchronous vs. asynchronous).

- Dependent Variables: Skin temperature response (a measure of body ownership); Proprioceptive drift (behavioral measure of body ownership); Self-reported body size estimation; Questionnaire measures of body satisfaction and eating disorder psychopathology.

Procedure:

- Pre-Test Baseline: Measure participants' body size estimation (e.g., using a body distortion task) and collect psychometric scales.

- Setup: Participant wears a head-mounted display (HMD) and stands in a tracked space.

- Embodiment Induction:

- The participant sees a virtual body from a first-person perspective, replacing their own.

- The researcher uses a rod to synchronously touch the participant's actual body and the corresponding part of the virtual body (e.g., the shoulder). This multisensory correlation induces a sense of body ownership over the avatar [1].

- Experimental Manipulation: Participants are randomly assigned to embody an avatar with a body size different from their own (e.g., healthier BMI).

- Post-Test: Immediately after the embodiment period, re-administer the body size estimation task and psychometric measures.

- Follow-Up: Conduct assessments at 1-week, 1-month, and 1-year intervals to test for long-term generalization.

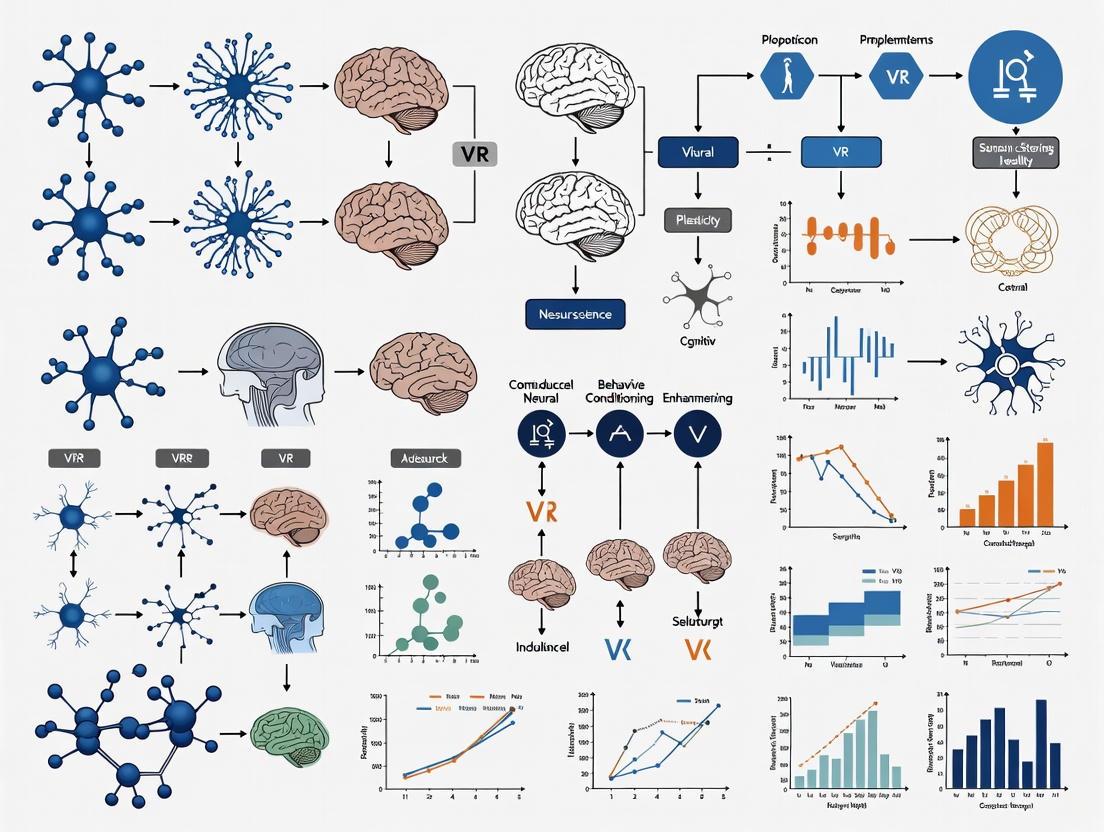

Visualization of Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the core inductive logic of the body swapping protocol.

A Model for Research: From Phenomenon to Publication

To systematically apply the embodied simulation framework in neuroscience research, a structured approach to modeling is essential. The following 10-step guide, adapted from Blohm et al. (2020), provides a robust pipeline for building computational models of brain and behavior in VR [5].

Table 2: A 10-Step Modeling Guide for Neuroscience Research in VR [5]

| Step | Action | Application to VR & Embodied Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Find a phenomenon and a question. | Define a specific behavioral phenomenon (e.g., proprioceptive drift in body ownership) and a clear "how" or "why" question. |

| 2 | Formalize your knowledge. | List all critical observations and existing knowledge about the phenomenon and the relevant VR parameters. |

| 3 | Find the central concept. | Identify the core concept from embodied simulation theory (e.g., "minimizing sensory prediction error") that can explain your phenomenon. |

| 4 | Select a mathematical framework. | Choose a framework that fits your concept (e.g., Bayesian inference for multisensory integration). |

| 5 | Implement the model. | Write the code, defining the state variables, parameters, and dynamics that implement your chosen framework. |

| 6 | Simulate the experiment. | Use your model to generate data for the same experimental task your human subjects undergo in VR. |

| 7 | Check model behavior. | Does the model's output qualitatively match the key features of your human data? |

| 8 | Optimize model parameters. | Fit your model to the experimental data to find the best-fitting parameters. |

| 9 | Validate the model. | Test the model's predictions on a new, held-out dataset to ensure it generalizes. |

| 10 | Publish. | Share your model, code, and data to enable replication and further scientific progress. |

Visualization of the Modeling Process: The flowchart below outlines the iterative, staged process of building a successful model for neuroscience research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To conduct rigorous experiments within the embodied simulation framework, specific technological and methodological "reagents" are required. The table below details these essential components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Embodied Simulation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Consumer-grade (Meta Quest, HTC Vive), Research-grade (Varjo) | Provides the immersive visual and auditory stimulus, tracking head movements to update the visual scene in real-time. Key for inducing presence. |

| Body Tracking Systems | Lighthouse tracking, Inside-out tracking, Motion capture suits (Vicon) | Tracks body and limb movements to animate a virtual avatar and/or update the user's perspective. Essential for studying agency and body ownership. |

| Haptic & Tactile Interfaces | Vibrotactile actuators, Force-feedback gloves (Dexmo), Haptic rods | Provides synchronous tactile and proprioceptive feedback to the user. Critical for inducing the rubber hand illusion and full-body ownership illusions. |

| Physiological Monitors | EEG, ECG, GSR (Galvanic Skin Response), EMG, Eye-tracking | Provides objective, continuous measures of cognitive/affective states (arousal, stress, engagement) during the VR experience, complementing self-report. |

| Software & Modeling Platforms | Unity, Unreal Engine, MATLAB, custom Bayesian modeling code | Used to create the virtual environments and to implement computational models that formalize hypotheses about the brain's predictive processes. |

The framework of embodied simulation represents a paradigm shift in behavioral neuroscience, positioning VR not merely as a fancy display technology, but as a unique tool for directly interfacing with the brain's fundamental computational mechanisms. By designing virtual environments that systematically manipulate the sensory cues contributing to the body matrix, researchers can rigorously test hypotheses about the construction of the self, emotion, and behavior. The experimental protocols and modeling guide provided here offer a concrete pathway for scientists to engage in this research.

Future work will likely focus on augmented embodiment—mapping difficult-to-perceive internal signals (e.g., neural activity, visceral state) to immersive sensory displays to enhance self-regulation [1]. Furthermore, as the parallels between the predictive brain and VR become even clearer, the vision of "embodied medicine" will advance: using targeted virtual simulations to directly alter pathological bodily processes for therapeutic effect, truly creating a "healthy mind in a healthy body" [1].

The Role of Presence and Immersion in Creating Therapeutic Realities

This technical guide examines the critical roles of presence (the subjective psychological experience of "being there" in a virtual environment) and immersion (the objective capability of the system to deliver a rich set of sensory stimuli) in creating effective virtual reality (VR) therapeutic interventions. Within theoretical frameworks for behavioral neuroscience research, these constructs provide the foundation for VR's mechanism of action across clinical applications. The interplay between technological immersion and psychologically mediated presence creates a powerful tool for manipulating perception, attention, and emotional processing—with significant implications for therapeutic outcomes in anxiety disorders, pain management, and neurological rehabilitation.

Theoretical Foundations in Behavioral Neuroscience

Defining the Core Constructs

In VR therapeutics, immersion and presence represent distinct but interrelated concepts fundamental to understanding its biological and psychological impacts. According to Slater and Wilbur's widely cited framework, immersion constitutes "an objective and quantifiable description of what any particular system does provide," while presence represents "a state of consciousness, the (psychological) sense of being in the virtual environment" [6]. This distinction is crucial for behavioral neuroscience research methodologies, as it separates the technical specifications of the VR system from the subjective experience they elicit.

From a neuroscience perspective, VR functions through embodied simulations that leverage the brain's innate predictive coding mechanisms. The brain continuously creates embodied simulations of the body in the world to regulate and control effective interaction with the environment [2]. VR technology essentially co-opts this fundamental neurological process by providing an external simulation that predicts the sensory consequences of an individual's movements, creating a compelling alternative reality that the brain accepts and processes similarly to real-world experiences [2].

Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic efficacy of VR primarily operates through several interconnected mechanisms:

Attentional Capture: VR reduces pain by "diverting attentional resources that would otherwise be used to process nociceptive signals" [6]. Functional MRI studies demonstrate that VR produces a 50% reduction in pain-related brain activity across five key regions: the primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, anterior cingulate, insula, and thalamus [6].

Emotional Processing: For anxiety disorders, VR facilitates emotional processing by activating and modifying fear memories through controlled exposure to feared stimuli in a safe environment [7]. This process allows for the incorporation of novel, incompatible information that updates maladaptive fear structures.

Embodied Cognition: By creating multisensory experiences that respond naturally to user movements, VR can alter the experience of the body and facilitate cognitive change through targeted virtual environments that simulate both external worlds and internal bodily states [2].

Quantitative Evidence for Therapeutic Efficacy

Clinical Outcomes Across Disorders

Table 1: Therapeutic Efficacy of VR Across Clinical Conditions

| Clinical Condition | Effect Size/Outcome | Comparison Condition | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders | Large treatment effects; small effect size favoring VRE over in-vivo | In-vivo exposure, waitlist | Meta-analytic results [7] |

| Specific Phobias | Similar efficacy to traditional evidence-based treatments | Waitlist, traditional exposure | Multiple RCTs [7] [2] |

| Flight Anxiety | Significant overall efficiency at post-test and follow-up | Control conditions, evidence-based interventions | Quantitative meta-analysis of 11 studies [2] |

| Acute Pain | 25% reduction in pain intensity; 23% increase in fun during stimulus | Semi-immersive VR, no VR | Randomized crossover study (n=72) [6] |

| Eating/Weight Disorders | Higher efficacy than gold-standard CBT at 1-year follow-up | Cognitive-behavioral therapy | 3 RCTs [2] |

| PTSD | Large effect sizes; significant symptom reduction | Waitlist, imaginal exposure | Multiple studies [7] [8] |

Presence and Immersion Metrics

Table 2: Technological and Psychological Factors Influencing Therapeutic Outcomes

| Factor | Definition | Impact on Therapeutic Outcomes | Empirical Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field of View | Angular extent of observable virtual world | Wider FOV increases presence and analgesia | Hoffman et al., 2006 [6] |

| Head Tracking | System ability to track and respond to head movements | Increases sense of presence and engagement | Slater & Wilbur, 1997 [6] |

| Interactivity | User ability to manipulate virtual environment | Significantly increases VR analgesia | Wender et al., 2009 [6] |

| Tactile Feedback | Haptic responses to user interactions | Enhances realism and therapeutic impact | Hoffman et al., 2023 [6] |

| Display Resolution | Number of pixels in VR goggles | Higher resolution reduces distraction and increases presence | Slater, 2018 [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized VR Exposure Therapy Protocol

For anxiety disorders, particularly specific phobias and PTSD, VR exposure therapy (VRET) follows a structured protocol:

Sessions 1-3: Psychoeducation regarding the specific disorder, psychosocial history assessment, overview of avoidance patterns, and rationale for exposures. Introduction to the process of VR-based exposures is provided, along with basic relaxation and/or coping strategies (e.g., breathing relaxation, cognitive restructuring) [7].

Subsequent Sessions: Conduct VR exposures where patients progress at an individualized pace through a graded exposure hierarchy. Each hierarchy step is repeated until anxiety decreases significantly, as measured by subjective units of distress ratings and behavioral observation [7].

Hierarchy Development: Content is typically preselected for specific disorders, with thorough assessment of the patient's fear or traumatic experience prior to exposure to individualize progression through hierarchy steps [7].

VR Analgesia Research Protocol

A recent randomized crossover study detailed a rigorous methodology for investigating VR's pain reduction mechanisms:

- Participants: 72 college students (mean age 19 years) [6].

- Design: Repeated measures crossover with conditions randomized.

- Conditions: No VR, semi-immersive VR (narrow field of view, no head tracking, no interactivity), and immersive VR (wide field of view, head tracking, interactivity) [6].

- Pain Stimulation: Brief, painful but safe and tolerable heat stimulations.

- Measures: Pain ratings (0-10 Graphic Rating Scale), fun ratings during stimulus, and performance on an attention-demanding odd-number divided-attention task [6].

- Analysis: Comparison of pain ratings and attention task errors across conditions, with secondary analyses for gender, race, and pain catastrophizing tendencies.

Diagram 1: VR Analgesia Study Experimental Workflow

Four-Stage Protocol for VR Implementation in Psychological Research

A comprehensive framework for implementing VR in psychological research and practice involves four key stages [8]:

Equipment Selection: Considerations include technical specifications, immersion capabilities, space limitations, resource demands, and integration capabilities with other hardware. Selection should be guided by the specific clinical population and research objectives [8].

Design and Development: Requires interdisciplinary collaboration between clinicians, researchers, and software developers. Investment in skill development and resources is essential, with end-user feedback incorporated throughout development [8].

Technology Integration: Combination of VR with other technologies (e.g., physiological recording, EEG, MRI) requires creative solutions and software development expertise. Important distinctions exist between open and closed platforms regarding customization capabilities [8].

Clinical Implementation: Successful adoption depends on appropriateness, acceptability, and feasibility within healthcare systems. Considerations include therapeutic alliance maintenance during immersion, development of training tools, and addressing unique ethical issues such as risk management and consent protocols [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Technologies for VR Therapeutics Research

| Research Reagent | Technical Function | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Provide visual and auditory immersion through head-locked displays | Primary interface for VR exposure therapy and analgesia |

| Gesture-Sensing Gloves | Enable natural interaction with virtual objects through hand tracking | Enhances sense of presence and agency in therapeutic environments |

| Vibrotactile Platforms | Deliver haptic feedback synchronized with virtual events | Increases realism and multisensory engagement |

| Eye-Tracking Systems | Measure gaze direction and pupillary responses within VR | Provides objective metrics of attention allocation during therapy |

| Physiological Monitoring | Records heart rate, skin conductance, EEG during VR sessions | Objective measurement of emotional and physiological arousal |

| Virtual Environment Software | Creates controlled, replicable therapeutic scenarios | Standardized delivery of exposure hierarchies and interventions |

| Head Tracking Systems | Updates visual display based on head position and orientation | Enhances spatial presence and reduces simulation sickness |

Signaling Pathways: Neurocognitive Mechanisms of VR Therapeutics

Diagram 2: Neurocognitive Pathways of VR Therapeutic Action

Future Directions and Research Agenda

The application of VR in behavioral neuroscience and therapeutics continues to evolve with several critical research frontiers:

Personalized VR Environments: Development of patient-specific virtual environments based on individual fear structures, trauma memories, or pain triggers [7] [8].

Neuromodulation Integration: Combination of VR with techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) shows preliminary positive results for pain management and rehabilitation [2].

Advanced Biomarkers: Integration of neuroimaging, eye-tracking, and physiological monitoring to develop objective biomarkers of presence and therapeutic engagement [8] [6].

Implementation Science: Systematic study of barriers to clinical adoption, including clinician training, resource allocation, and treatment fidelity across settings [8].

Mechanism Refinement: Further elucidation of the temporal dynamics between immersion, presence, and therapeutic change, particularly through rigorous attention measurement as demonstrated in recent analgesia studies [6].

The integration of presence and immersion within theoretical frameworks for behavioral neuroscience offers powerful methodological opportunities for studying human perception, attention, and emotion in ecologically valid yet controlled environments. As technological capabilities advance and research methodologies become more sophisticated, VR continues to establish its value as both an investigative tool in neuroscience and a transformative modality in therapeutic applications.

The integration of Virtual Reality (VR) into behavioral neuroscience research represents a paradigm shift, enabling unprecedented investigation of learning and meaning-making processes. This transformation is rooted in the powerful convergence of constructivist and situated cognition theories with immersive technologies. Constructivist learning theory posits that knowledge is not passively received but actively built by the learner based on their existing cognitive structures and experiences [9]. Simultaneously, situated cognition theory maintains that learning and knowledge are fundamentally tied to the context and environment in which they are developed [9]. VR technology serves as the ideal experimental platform where these theoretical frameworks intersect, allowing researchers to create controlled yet ecologically valid environments where participants actively construct knowledge within situated contexts [9] [10].

The significance for behavioral neuroscience research lies in VR's capacity to standardize complex experimental tasks while maintaining high ecological validity. By closing "the gap between protocol intent and participant execution," VR converts multi-step instructions into timed, spatially constrained tasks with real-time coaching, yielding lower variance and cleaner audit trails than traditional methods [11]. This technological capability aligns perfectly with the needs of contemporary research, particularly in pharmaceutical development and clinical trials, where understanding the neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying learning can accelerate therapeutic discovery [11] [12].

Theoretical Foundations for VR-Enhanced Learning

Constructivist Learning Theory in Virtual Environments

Constructivism maintains that learning is an active process where learners construct new knowledge based on their prior experiences and interactions with their environment [9] [13]. The four fundamental elements of constructivist learning—situation, collaboration, conversation, and meaning construction—find unique expression in VR environments [9]. In constructivist theory, the learning process is characterized by three essential attributes: initiative (learners actively construct knowledge), diversity and heterogeneity (different individuals construct different knowledge structures), and collaborative learning (knowledge is built through social negotiation) [9].

In VR-enhanced constructivist learning, environments can be dynamically designed to present problems and scenarios that require learners to actively explore and develop their own understanding. Rather than passively receiving information, participants in VR experiments manipulate virtual objects, navigate complex spatial environments, and observe the consequences of their actions, thereby constructing mental models through direct experience [10]. This approach stands in stark contrast to traditional behavioral paradigms where stimuli and responses are often severely constrained.

Situated Cognition Theory in Virtual Environments

Situated cognition theory emphasizes that knowledge and learning are fundamentally situated in the specific context and activity in which they are developed [9]. This theoretical framework challenges the notion that knowledge can be abstracted from the situations in which it is used and argues that learning is inseparable from the environment and practice in which it occurs [9]. Situated cognition thus positions practice not as independent of learning, but as integral to it, with meaning emerging from the interaction between practice and situational context [9].

VR technology offers powerful applications for situated cognition by enabling researchers to create authentic, context-rich environments that closely mimic real-world settings while maintaining experimental control [10] [14]. These virtual environments allow for the study of cognitive processes within realistic contexts, addressing a significant limitation of traditional laboratory-based experiments. For behavioral neuroscience, this means that tasks such as spatial navigation, decision-making, and social cognition can be studied in environments that closely resemble real-world scenarios, thereby enhancing the ecological validity of findings [14] [15].

Theoretical Alignment of VR with Learning Frameworks

The pedagogical value of VR in neuroscience research and education is strongly supported by its alignment with contemporary learning theories that emphasize active, experiential, and situated engagement [10]. Embodied cognition, a theoretical framework linking motor experiences to cognitive processes, offers further support for immersive learning approaches [10]. As participants physically interact with virtual structures using motion controls and spatial navigation, they deepen their understanding through sensory-motor engagement, activating neural pathways that support deeper learning and retention [10].

Cognitive load theory also plays a critical role in designing effective VR experiments for behavioral neuroscience. The design of immersive learning experiences must balance intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load to optimize learning outcomes [10]. In neuroscience research contexts, this involves sequencing experimental tasks from simple to complex, integrating multimodal feedback, and providing appropriate scaffolding to support participants with different cognitive abilities and prior experiences [10].

Quantitative Validation of VR-Enhanced Learning

Empirical studies across multiple domains have demonstrated the efficacy of VR-enhanced learning approaches grounded in constructivist and situated cognition principles. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research:

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence for VR-Enhanced Learning Across Domains

| Domain | Performance Metric | Improvement | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Cognitive Learning | Learning efficiency | ≥20% improvement compared to traditional methods [9] | VR-enhanced campus knowledge learning |

| Precision Motor Skills | Shot scores | 13% average improvement across visits [12] | Simulated marksmanship in immersive VR |

| Motor Learning | Hand reaction times | Significant decrease with practice [12] | Visuomotor task in interactive VR |

| Motor Learning | Spatial precision | Significant increase with practice [12] | Three-visit motor task in VR |

| Clinical Applications | Neurocognitive batteries | Standardized testing with reduced variance [11] | Clinical trial settings |

| Motor Function Assessment | Fine-motor precision | Improved tremor grading and measurement [11] | Parkinson's and MS clinical research |

These quantitative findings demonstrate that VR environments grounded in constructivist and situated cognition principles can significantly enhance learning outcomes across diverse domains. The 20% improvement in learning efficiency reported in general cognitive learning aligns with performance enhancements observed in motor learning tasks, suggesting common underlying mechanisms [9] [12]. For behavioral neuroscience research, these findings validate VR as not merely an immersive presentation tool but as a powerful platform for enhancing cognitive and motor learning processes.

The neural mechanisms underlying these performance improvements are increasingly being uncovered through neurophysiological investigations. Studies combining VR with EEG have revealed that "spectral and time-locked analyses of the EEG beta band (13-30 Hz) power measured prior to target launch and visual-evoked potential amplitudes measured immediately after the target launch correlated with subsequent reactive kinematic performance" [12]. Furthermore, practice-related changes in "launch-locked and shot/feedback-locked visual-evoked potentials became earlier and more negative with practice, pointing to neural mechanisms that may contribute to the development of visual-motor proficiency" [12].

Experimental Protocols for VR-Enhanced Learning Research

Protocol 1: Visuomotor Integration and Learning Assessment

This protocol measures neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying precision visual-motor control, adapting experimental paradigms from existing VR research [12].

Materials and Setup:

- Immersive VR system with head-mounted display and motion tracking

- EEG system with appropriate data synchronization capabilities

- Virtual environment simulating a coincidence-anticipation task (modeled after target shooting)

- Data recording system for kinematic measures and neural activity

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Apply EEG electrodes according to standard positioning guidelines (10-20 system). Ensure proper impedance values (<5 kΩ) for all electrodes.

- Baseline Assessment: Record resting-state EEG for 5 minutes (eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions).

- Task Familiarization: Introduce participants to the VR environment and task requirements through 10 practice trials.

- Experimental Trials:

- Present targets in random sequences across multiple trials (recommended: 60 trials per session)

- Record kinematic data including hand reaction times, trigger response times, and spatial precision

- Synchronize EEG recording with task events (target launch, participant response, feedback)

- Post-Task Assessment: Administer subjective measures of presence and cognitive load.

- Longitudinal Testing: Repeat the protocol across multiple sessions (e.g., three visits) to assess learning effects.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate performance metrics including shot scores, reaction times, and movement efficiency

- Perform spectral analysis of EEG beta band (13-30 Hz) power preceding target launch

- Analyze event-related potentials time-locked to target launch and participant response

- Correlate neural measures with behavioral performance across learning sessions

Protocol 2: Executive Function Assessment in Pediatric Populations

This protocol adapts VR methodologies for assessing executive functions in clinical pediatric populations, based on research with neurodevelopmental disorders [15].

Materials and Setup:

- Immersive VR system with appropriate safety considerations for children

- Custom VR environments targeting specific executive functions (inhibition, cognitive flexibility, working memory)

- Age-appropriate interface devices ensuring comfortable interaction

- Data logging capabilities for performance metrics

Procedure:

- Screening and Consent: Obtain informed consent from parents/guardians and assent from children. Screen for motion sickness susceptibility and visual impairments.

- Environment Orientation: Allow 5-10 minutes for participants to acclimate to the VR environment through neutral exploration.

- Executive Function Assessment:

- Inhibition Task: Virtual "go/no-go" paradigm with engaging stimuli

- Cognitive Flexibility Task: Virtual dimensional card sort task with changing rules

- Working Memory Task: Spatial navigation task with increasing memory load

- Ecological Validity Assessment: Compare VR performance with traditional neuropsychological measures and parent/teacher ratings.

- Post-Task Interview: Collect subjective feedback on engagement, presence, and task difficulty.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate accuracy rates, reaction times, and error types for each executive function domain

- Assess learning curves across task blocks and trials

- Analyze transfer effects to real-world functioning through correlational analyses with parent/teacher reports

Visualization Framework for VR Learning Processes

The following diagrams illustrate the theoretical relationships and experimental workflows central to understanding constructivist and situated learning in virtual environments.

Theoretical Integration Framework

Experimental Implementation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for VR Learning Studies

The following table outlines essential tools and methodologies for implementing VR learning studies grounded in constructivist and situated cognition principles.

Table 2: Essential Research Components for VR Learning Studies

| Research Component | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR HMD Systems | Creates controlled yet ecologically valid environments | Motor learning, spatial navigation studies [12] [14] |

| EEG Integration Systems | Captures neural correlates of learning processes | Investigating neurophysiological mechanisms of VR learning [12] |

| Motion Tracking Systems | Quantifies kinematic movements and interactions | Precision motor control assessment, rehabilitation monitoring [12] [15] |

| Custom VR Task Environments | Implements constructivist learning principles through interactive scenarios | Executive function assessment, clinical rehabilitation [15] |

| Physiological Monitoring | Measures autonomic responses during learning | Arousal, engagement, and cognitive load assessment [14] |

| Presence and Cognitive Load Questionnaires | Assesses subjective experience and mental effort | Validating ecological validity, optimizing task difficulty [10] |

These research components enable the comprehensive investigation of learning processes within virtual environments. The integration of neural, behavioral, and subjective measures provides a multidimensional understanding of how knowledge construction occurs in situated contexts. For behavioral neuroscience research, this toolkit facilitates the exploration of fundamental questions about the relationships between brain activity, cognitive processes, and learning outcomes in environments that balance experimental control with ecological validity.

The integration of constructivist and situated cognition theories with VR technology represents a transformative approach for behavioral neuroscience research. By creating environments that support active knowledge construction within meaningful contexts, researchers can investigate learning processes with unprecedented ecological validity and experimental control. The quantitative evidence demonstrates significant improvements in learning efficiency and performance across domains, validating VR as a powerful platform for studying and enhancing human learning.

Future research directions should focus on further elucidating the neural mechanisms underlying VR-enhanced learning, optimizing individual differences in response to immersive learning environments, and developing standardized assessment protocols that leverage the unique capabilities of VR technology. As VR systems become more accessible and sophisticated, their potential to advance our understanding of learning and cognition while simultaneously enhancing real-world performance will continue to grow, offering exciting opportunities for researchers and practitioners alike.

Virtual reality (VR) has transitioned from a speculative technology to a clinically validated tool for inducing and measuring neuroplasticity—the brain's fundamental capacity to reorganize its structure, connections, and function in response to experience [16] [17]. Unlike traditional laboratory tasks, VR offers unprecedented control over multi-sensory inputs within ecologically valid, immersive environments, enabling researchers to systematically manipulate parameters to target specific neural circuits [16]. This capacity positions VR as a powerful experimental platform within behavioral neuroscience research, particularly for developing theoretical frameworks that bridge molecular mechanisms, systems-level neural reorganization, and behavioral outcomes. By creating dynamic, interactive scenarios that engage multiple sensory modalities simultaneously, VR environments foster a rich sensory experience thought to encourage synaptic reorganization and cortical remapping through mechanisms such as cross-modal plasticity [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, VR provides not only an intervention tool but also a precise measurement platform for quantifying neuroplastic changes in response to pharmacological, behavioral, or combined therapies, offering biomarkers with high temporal resolution and functional relevance.

Core Mechanisms of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

The therapeutic and research applications of VR are underpinned by specific, measurable mechanisms that directly engage the brain's plastic capabilities. These mechanisms work synergistically to promote adaptive neural changes.

Error-Based Learning with Real-Time Feedback

Advanced VR platforms capture real-time kinematic and performance data, creating a closed-loop system that provides immediate feedback, reinforcing correct movements and discouraging maladaptive patterns [17]. This process engages cerebellar-thalamocortical circuits and reinforcement learning pathways involving dopaminergic signaling from the ventral tegmental area to the striatum [17]. Evidence suggests such feedback facilitates the strengthening of residual pathways and accelerates recovery, with studies demonstrating improvements in balance across various neurologic conditions and forced corrective adjustments through error augmentation techniques [17].

Multisensory Integration and Cortical Reorganization

VR's capacity to concurrently engage visual, auditory, and proprioceptive systems creates a rich sensory experience that promotes cross-modal plasticity through mechanisms such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and dendritic remodeling [17]. This has been demonstrated to facilitate motor learning after stroke through reorganization from aberrant ipsilateral sensorimotor cortices to the contralateral side [17]. Environments combining auditory cues with visual stimuli in patients with traumatic brain injury and stroke with hemianopia or neglect improve compensatory scanning and attention, providing proof-of-principle for this mechanism [17].

Virtual Embodiment and Mirror Neuron Activation

VR mirror therapy leverages the mirror neuron system by reflecting movements of an intact limb, activating motor pathways of the affected side through visuomotor integration [17]. The visual reappearance of self-actions in the VR scene further stimulates activity in affected cortical areas—primarily premotor cortex and inferior parietal lobule—promoting their functional integration [17]. VR-based motor imagery exercises increase cortical mapping of areas corresponding to trained muscles and excitability of the corticospinal tract, ultimately facilitating motor relearning [17].

Reward-Mediated Learning and Cognitive Engagement

Gamification and immersive scenarios engage the brain's intrinsic reward systems, stimulating dopaminergic pathways in the ventral striatum that are crucial for motivation, reinforcement learning, and long-term potentiation [17]. The interactive, goal-oriented nature of VR enhances cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and executive control while simultaneously increasing patient adherence to therapeutic protocols—a critical factor in driving sustained neuroplastic changes [17].

Table 1: Neuroplasticity Mechanisms Targeted by VR Interventions

| Mechanism | Neural Circuits Involved | VR Application Examples | Measurable Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Based Learning | Cerebellar-thalamocortical circuits, Striatal dopamine pathways | Real-time movement correction in motor rehabilitation [17] | Improved movement accuracy, Reduced compensatory patterns |

| Multisensory Integration | Superior colliculus, Parieto-insular vestibular cortex, Associative cortices | Combining visual, auditory, and balance cues for neglect rehabilitation [17] | Enhanced cross-modal processing, Improved spatial awareness |

| Mirror Neuron Activation | Premotor cortex, Inferior parietal lobule, Primary motor cortex | VR mirror therapy for stroke recovery [17] | Increased motor cortex excitability, Improved bilateral coordination |

| Reward-Mediated Learning | Ventral striatum, Prefrontal cortex, Ventral tegmental area | Gamified cognitive tasks with scoring and progression [17] | Enhanced motivation, Improved learning retention, Dopamine release markers |

Quantitative Evidence of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

Rigorous empirical studies across neurological and psychiatric populations provide compelling evidence for VR's capacity to induce measurable neuroplastic changes at molecular, systems, and behavioral levels.

Neurophysiological Changes in Stroke Rehabilitation

A 2023 study investigating VR cognitive training in chronic stroke patients (n=30) revealed significant electrophysiological changes consistent with neuroplasticity [18]. Quantitative EEG analysis demonstrated that VR-based rehabilitation resulted in a significant increase in alpha band power (8-13 Hz) in occipital areas and elevated beta band power (13-30 Hz) in frontal regions, while no significant variations were observed in theta band power [18]. These frequency-specific changes indicate enhanced neural efficiency in sensory integration and cognitive processing networks, respectively. The experimental protocol involved 15 patients receiving neurocognitive stimulation using the VRRS Evo-4 device, while 15 controls received the same amount of conventional neurorehabilitation, with EEG recordings conducted pre- and post-intervention [18].

Multimodal Biomarkers in Adolescent Depression

A 2025 case-control study (n=115) utilizing a VR-based multimodal framework for adolescent major depressive disorder identified robust physiological biomarkers of therapeutic change [19]. Adolescents with MDD showed significantly higher EEG theta/beta ratios, reduced saccade counts, longer fixation durations, and elevated HRV LF/HF ratios (all p<.05) compared to healthy controls [19]. Both theta/beta and LF/HF ratios were significantly associated with depression severity, and a support vector machine model achieved 81.7% classification accuracy with an AUC of 0.921 based on these VR-elicted biomarkers [19]. The experimental protocol involved a 10-minute VR emotional task with a virtual agent named "Xuyu" in a magical forest environment, while synchronized EEG, eye-tracking, and HRV data were collected [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Biomarkers of Neuroplasticity in VR Studies

| Study Population | VR Intervention | Measurement Technique | Key Neuroplasticity Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Stroke Patients (n=30) [18] | VRRS cognitive training | Quantitative EEG | ↑ Alpha power (occipital), ↑ Beta power (frontal) |

| Adolescent MDD (n=115) [19] | 10-min emotional task with virtual agent | Multimodal (EEG+ET+HRV) | ↑ EEG theta/beta ratio, Altered oculometrics, ↑ HRV LF/HF ratio |

| Psychosis with AVHs (n=10 planned) [20] | VR + EEG neurofeedback + CBTp | EEG neurofeedback | Self-modulation of high-β activity (target) |

| Healthy Adults (Social Skills, n=114) [4] | Job interview training | Behavioral metrics | ↑ Task-specific self-efficacy, ↓ Anxiety (4-month retention) |

Integrated Neuroplasticity Pathways in VR

The following diagram illustrates the primary neuroplasticity pathways engaged during VR interventions, from multisensory input to functional recovery:

Experimental Protocols for Measuring VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

Standardized methodologies are essential for rigorous investigation of VR's effects on neural circuits. The following protocols represent current best practices in the field.

VR with Simultaneous Electrophysiology

Application: Quantifying neuroplastic changes during cognitive rehabilitation in stroke [18] and detecting biomarkers in adolescent depression [19].

Protocol Details:

- Setup: High-density EEG (64+ channels) synchronized with VR presentation system. Eye-tracking and ECG/HRV monitoring integrated for multimodal assessment [19] [18].

- Stimuli: Custom VR environments developed using frameworks like A-Frame, presenting graded cognitive-motor tasks or emotionally engaging scenarios [19].

- Procedure: Baseline recording (5 mins) → VR task period (10-30 mins) → Post-VR recording (5 mins). Task parameters adapt based on performance in closed-loop designs [18].

- Data Analysis: Time-frequency decomposition (ERD/ERS), functional connectivity metrics (coherence, phase-locking value), source localization, and correlation with behavioral measures [18].

Key Controls: Sham VR condition with matched visual stimulation but no interactive component, counterbalanced order, strict minimization of movement artifacts [18].

VR with Neurofeedback for Circuit-Specific Modulation

Application: Targeting auditory verbal hallucinations in psychosis [20] and enhancing cognitive control in various disorders.

Protocol Details:

- Setup: EEG-based neurofeedback system integrated with immersive VR environment. Real-time signal processing with <100ms latency [20].

- Neurofeedback Target: Individualized based on symptom signature (e.g., high-β power for AVHs) [20].

- Procedure: "Symptom capture" approach using individually tailored VR-based exposure exercises. Participants learn to downregulate target neural activity while progressively exposed to symptom triggers [20].

- Therapeutic Integration: Clinician-delivered CBTp concurrently with neurofeedback training (12 weekly sessions) [20].

Outcome Measures: Self-directed modulation of target neural activity, progression through VR exposure hierarchy, symptom change scores on standardized scales [20].

Experimental Workflow for VR Neuroplasticity Research

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for designing and executing studies investigating VR-induced neuroplasticity:

Implementing rigorous VR neuroplasticity research requires specific technological components and methodological considerations.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for VR Neuroplasticity Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | VRRS Evo-4 [18], HTC Vive, Oculus Rift | Provide immersive environments with head-mounted displays and motion tracking | Level of immersion (full vs. semi), tracking precision, compatibility with research software |

| Neurophysiology Acquisition Systems | BIOPAC MP160 [19], BrainVision, BioSemi | Synchronized recording of EEG, ECG, EDA, EMG | Integration latency, sampling rate, artifact handling capabilities |

| Software Development Frameworks | A-Frame [19], Unity3D, Unreal Engine | Creation of custom VR environments with precise experimental control | Scripting capabilities, compatibility with research equipment, community support |

| Data Analysis Toolboxes | EEGLAB, FieldTrip, Custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Processing of neural signals, behavioral metrics, and their relationships | Support for multimodal data fusion, statistical analysis, machine learning pipelines |

| Experimental Paradigms | VR mirror therapy [17], Social evaluation tasks [4], Emotional provocation [19] | Standardized protocols for inducing and measuring targeted neural processes | Psychometric validation, sensitivity to change, translational relevance |

VR represents a transformative tool for investigating and harnessing neuroplasticity within theoretical frameworks for behavioral neuroscience research. By enabling precise control over multi-sensory inputs within ecologically valid environments, VR allows researchers to target specific neural circuits and measure resulting plastic changes with high temporal resolution [16] [17]. The mechanisms outlined—error-based learning with real-time feedback, multisensory integration, virtual embodiment, and reward-mediated learning—provide a foundation for understanding how VR interventions produce measurable neuroplastic changes at molecular, systems, and behavioral levels [17].

Future research directions should focus on optimizing immersion levels for specific clinical populations [21], standardizing VR-based biomarkers for drug development trials [11], and developing closed-loop systems that automatically adapt VR parameters in real-time based on neural activity [16] [20]. For the pharmaceutical industry, VR platforms offer promising endpoints for clinical trials, potentially detecting therapeutic effects with greater sensitivity than conventional behavioral measures [11] [18]. As VR technology continues to evolve, its integration with other emerging technologies like AI-powered virtual humans [22] and wearable biosensors [19] will further enhance its utility for promoting adaptive neuroplasticity across a wide spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

From Theory to Practice: VR Methodologies for Assessment and Intervention

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents a paradigm shift in behavioral neuroscience and therapeutic intervention, grounded firmly in the principles of extinction learning. As an innovative form of exposure therapy, VRET utilizes immersive virtual environments to systematically and safely expose individuals to feared stimuli, facilitating the formation of new, non-threatening associations through inhibitory learning processes [23] [2].

The theoretical foundation of VRET rests upon its capacity to create controlled, repeatable, and customizable environments that engage the same neurobiological mechanisms as real-world exposure while offering superior experimental control for research purposes [23]. By leveraging advanced immersive technology, VRET enables researchers and clinicians to target the precise neural circuits involved in fear acquisition and extinction, particularly within amygdala-prefrontal cortex interactions [2] [24]. This technical guide explores the mechanistic basis of VRET within the context of contemporary extinction learning theories and their implications for behavioral neuroscience research and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations: Extinction Learning Principles

The Mechanisms of Extinction Learning

Extinction learning involves the gradual reduction of conditioned fear responses through repeated, non-reinforced exposure to feared stimuli, resulting in the formation of new safety memories that compete with original fear memories [2]. Within immersive VR environments, this process occurs through several interconnected mechanisms:

Memory Reconsolidation Interference: VRET creates opportunities to reactivate fear memories within virtual environments and introduce mismatching information (safety cues), potentially altering the original fear memory trace upon reconsolidation [2].

Inhibitory Learning Development: The brain creates new, inhibitory associations that compete with original fear associations through repeated virtual exposure without adverse consequences, engaging prefrontal regulation of amygdala activity [2] [24].

Contextual Encoding: VR environments provide rich contextual cues that enhance the encoding and retrieval of extinction memories, with the virtual context serving as a retrieval cue for safety learning [23].

Embodied Simulation: According to neuroscience research, the brain maintains embodied simulations of the body in the world to represent and predict actions, concepts, and emotions [2]. VR works through a similar mechanism, providing users with simulated experiences that the brain processes using the same neural machinery as real experiences, thereby facilitating genuine extinction learning.

Neurobiological Substrates of VRET

Research utilizing the SONIA VR system for exploring anxiety-related brain networks has identified key neural structures engaged during virtual exposure, including the amygdala, hippocampus, striatum, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), hypothalamus, and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) [24]. These structures form interconnected subsystems regulating cognitive control, fear conditioning, uncertainty anticipation, motivation processing, and stress regulation – all of which are modulated during VRET through targeted virtual experiences [24].

Functional imaging studies reveal that successful extinction learning during VRET correlates with increased prefrontal activation coupled with diminished amygdala responsiveness, reflecting the shift from emotional reactivity to cognitive regulation [2]. The immersive nature of VR enhances engagement of these neural circuits by providing multisensory input that creates strong feelings of presence, thereby increasing the ecological validity of the extinction learning experience compared to imaginal exposure [23] [2].

VRET Efficacy: Comparative Evidence and Mechanisms

Clinical Efficacy Across Disorders

Table 1: VRET Efficacy Across Anxiety Disorders

| Disorder | Effect Size vs. Control | Comparison to In-Vivo Exposure | Long-Term Maintenance | Key Supporting Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobias | Large effects (g > 0.80) | Equivalent efficacy | Maintained at follow-up | Systematic reviews [25] [2] |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | Moderate to large effects | Comparable outcomes | 3-12 month persistence | Meta-analysis [25] |

| PTSD | Significant symptom reduction | Non-inferiority demonstrated | Generalization to real world | Multiple RCTs [23] [2] |

| Panic Disorder | Clinical improvement | Similar mechanisms | Reduced relapse | Neuroimaging studies [2] |

Recent meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that VRET generates positive clinical outcomes in the treatment of specific phobias and social anxiety disorders that are comparable to in-vivo exposure therapy (IVET), with both approaches reporting moderate effect sizes [25]. The analysis suggested that both are equally effective at reducing social phobia and anxiety symptoms, though the limited literature makes it difficult to identify which approach is optimal for specific patient subgroups [25].

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Active Components

Table 2: Therapeutic Mechanisms in VRET

| Mechanism | VRET Application | Measurable Outcomes | Research Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Engagement | Presence metrics, physiological arousal | Stronger extinction with higher presence | Psychophysiological studies [2] |

| Stimulus Control | Graduated exposure hierarchies | Systematic fear reduction | Clinical trials [23] [25] |

| Contextual Manipulation | Multiple virtual environments | Enhanced extinction generalization | Fear renewal paradigms [23] |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | Virtual behavioral experiments | Changed threat expectancies | Self-report measures [2] |

| Inhibitory Learning | Violation of fear expectations | Development of competing associations | Learning curves [2] [25] |

The effectiveness of VRET is mediated through multiple active components, with presence (the subjective experience of being in the virtual environment) and emotional engagement serving as crucial mediators of therapeutic outcome [2]. Research indicates that the immersive quality of VR "hijacks" the user's auditory, visual, and proprioception senses, acting as a distraction that limits the ability to process stimuli from the real world and creating potent conditions for new learning [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized VRET Protocol for Anxiety Disorders

A typical VRET protocol for anxiety disorders involves multiple structured sessions incorporating the following components:

Psychoeducation (Session 1): Explanation of the extinction learning model, rationale for virtual exposure, and introduction to the VR equipment.

Fear Hierarchy Development (Session 1): Collaborative creation of individualized fear hierarchy with subjective units of distress (SUDs) ratings for virtual scenarios.

Graduated Exposure (Sessions 2-8): Systematic progression through fear hierarchy, beginning with moderately anxiety-provoking scenarios and advancing to more challenging situations.

Within-Session Habituation: Continued exposure to each virtual scenario until SUDs decrease by 50% or more.

Between-Session Practice: Repeated practice of successfully completed exposures to strengthen extinction learning.

Relapse Prevention (Final Session): Review of progress, anticipation of future challenges, and development of maintenance plan.

Session duration typically ranges from 45-90 minutes, with the number of sessions varying based on disorder complexity (specific phobias: 1-5 sessions; PTSD: 8-15 sessions) [23] [25].

Specialized Protocol for PTSD Treatment

VRET for PTSD requires additional considerations for trauma memory processing:

Trauma Narrative Development: Detailed assessment of trauma memories to create authentic virtual scenarios.

Therapeutic Alliance Strengthening: Enhanced focus on therapist-patient rapport given the sensitivity of trauma material.

Dual Attention Components: Incorporation of grounding elements within the virtual environment to maintain connection to present safety.

Emotional Processing Measures: Regular assessment of trauma-related emotions and cognitions throughout exposure.

Meaning-Making Integration: Discussion of changed perspectives regarding trauma identity and post-traumatic growth [23].

Research demonstrates that VRET for PTSD is particularly effective when it allows for emotional engagement with trauma memories while maintaining awareness of current safety, facilitating corrective emotional experiences that modify the fear structure [23] [2].

Technical Implementation and System Requirements

Immersive Technology Specifications

Modern VRET systems utilize a range of technological components to create convincing therapeutic environments:

Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs): Modern HMDs like the Oculus Rift or HTC Vive provide high-resolution displays (≥1080x1200 per eye), wide field of view (≥100 degrees), and precise head tracking (6 degrees of freedom) to create immersive experiences [23] [26]. These HMDs are relatively easy to use and program, with good display quality and affordable prices, making them suitable for both research and clinical applications [26].

Interaction Devices: Hand controllers, data gloves, or gesture recognition systems enable natural interaction with virtual environments, enhancing agency and presence.

Physiological Monitoring: Integrated biosensors (heart rate, skin conductance, respiration) provide objective measures of emotional arousal during exposure.

Software Platforms: Game engines like Unity or Unreal Engine enable creation of customizable virtual environments with realistic graphics and physics [24].

The multi-scale interaction paradigm implemented in systems like SONIA allows users to manipulate both enlarged environmental contexts and detailed anatomical models, facilitating both situational exposure and psychoeducation about neurophysiological responses [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for VRET Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for VRET Experiments

| Research Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized VR Environments | Provide consistent exposure stimuli across participants | Virtual public speaking auditorium, height scenarios, flight simulations [23] |

| Presence Questionnaires | Measure subjective immersion in virtual environments | Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ), Slater-Usoh-Steed Questionnaire [26] |

| Fear Response Measures | Quantify anxiety and fear during exposure | Subjective Units of Distress (SUDs), Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale [25] |

| Physiological Recording | Objective assessment of arousal states | Skin conductance response, heart rate variability, respiratory rate [2] |

| Cognitive Assessment | Measure changes in threat-related cognitions | Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale, Thought Listing Procedures [2] |

| Neural Activity Monitoring | Identify neurobiological correlates of extinction | fMRI, EEG during or post-VRET [2] [24] |

Visualization: Extinction Learning Mechanisms in VRET

The following diagram illustrates the primary psychological and neurobiological mechanisms through which VRET facilitates extinction learning:

VRET Extinction Learning Pathway:

This visualization outlines the proposed pathway through which Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy facilitates extinction learning, connecting key psychological mechanisms with their underlying neural substrates and resulting behavioral outcomes.

Future Directions and Research Applications

Emerging Research Paradigms

The future of VRET research involves several promising directions that leverage advancing technology to enhance extinction learning:

Personalized Virtual Environments: Creation of patient-specific scenarios using photogrammetry and 3D scanning to increase relevance and emotional engagement.

Real-Time Biofeedback: Integration of physiological data to dynamically adjust virtual environments based on arousal states.

Augmented Reality Exposure: Blending of virtual elements with real environments to enhance generalization of extinction learning.

Neuromodulation Integration: Combination of VRET with non-invasive brain stimulation (tDCS, TMS) to potentiate extinction learning [2] [27].

Digital Twin Technology: Development of highly customized digital replicas of patients to model individual responses and optimize treatment parameters [27].

Implications for Drug Development

VRET protocols offer valuable paradigms for evaluating novel pharmacological agents that target learning and memory processes:

Cognitive Enhancers: VRET provides a controlled platform for testing compounds designed to facilitate extinction learning (e.g., D-cycloserine, glucocorticoids).

Fear Memory Modulators: The reconsolidation window during VRET creates opportunities to test compounds that disrupt maladaptive fear memories.

Translational Biomarkers: VRET responses can serve as functional biomarkers for target engagement in clinical trials of neurotherapeutic agents [2].

The combination of VRET with pharmacological approaches represents a promising frontier for developing enhanced treatments for anxiety, trauma, and stress-related disorders, potentially offering synergistic effects that produce more robust and durable extinction learning [2] [26].

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy represents a theoretically grounded and empirically validated approach that leverages the core mechanisms of extinction learning to address maladaptive fear and anxiety. Its foundation in embodied simulation theory – which posits that VR shares with the brain the same basic mechanism of creating predictive models of reality – provides a compelling explanation for its efficacy [2]. By engaging both the psychological processes of emotional engagement and cognitive reappraisal, along with the neurobiological substrates of fear extinction, VRET creates optimal conditions for inhibitory learning and the development of new safety associations.

For researchers in behavioral neuroscience and drug development, VRET offers a highly controlled, precisely measurable, and ethically advantageous paradigm for investigating the mechanisms of fear extinction and testing novel therapeutic interventions. The continuing evolution of immersive technology promises to further enhance the ecological validity, accessibility, and personalization of VRET, solidifying its position as an indispensable tool in the future of mental health research and treatment.

Virtual reality (VR) technology is revolutionizing the study and treatment of addiction by providing unprecedented methodological rigor and ecological validity. By creating controlled, immersive environments that simulate real-world contexts, VR enables researchers to probe the complex mechanisms of cue reactivity and craving—core phenomena in substance use disorders (SUDs). Cue reactivity describes the patterned response to stimuli associated with substance use, while craving represents the subjective experience of urge or desire for the substance [28]. The DSM-5 recognizes craving as a crucial diagnostic criterion for SUDs and a significant predictor of relapse [28]. Traditional laboratory methods for studying craving, such as static images or videos, lack the immersive quality necessary to trigger robust, real-world craving responses. VR technology addresses this limitation by enabling the construction of complex, multi-sensory environments that incorporate both proximal cues (e.g., drugs, paraphernalia) and contextual cues (e.g., social settings, environments) that are known to trigger craving in daily life [28] [29]. This technical guide examines the theoretical frameworks, experimental paradigms, and practical applications of VR for investigating cue reactivity and craving within behavioral neuroscience research on addiction.

Theoretical Frameworks for VR in Addiction Neuroscience

Classical Conditioning and Extinction Learning

The application of VR in addiction research is predominantly grounded in classical conditioning theory. Through repeated pairings, substance-related stimuli (conditioned stimuli - CS) become associated with the drug's effects (unconditioned stimuli - UCS), eventually eliciting conditioned responses (CR) including craving and physiological reactions [28]. VR-based cue exposure therapy (CET) leverages this framework through extinction learning, where repeated presentation of drug cues without actual substance consumption weakens the conditioned response [30].

From a neurocognitive perspective, addiction represents an imbalance between reflexive (impulsive) and reflective (regulatory) systems [28]. The reflexive system, associated with limbic and striatal regions, drives automatic drug-seeking behavior, while the reflective system, dependent on prefrontal cortical areas, provides cognitive control. VR paradigms uniquely engage both systems simultaneously by presenting emotionally salient cues while requiring active behavioral responses, thus providing a window into their dynamic interaction.

Ecological Validity and Presence

A primary theoretical advantage of VR is its ability to enhance ecological validity—the degree to which experimental findings generalize to real-world settings [28] [14]. Traditional craving induction methods suffer from limited contextual cues, whereas VR environments can simulate complex real-world scenarios such as bars, parties, or social gatherings where substance use typically occurs [28] [31].

The effectiveness of VR in eliciting genuine craving responses depends critically on presence—the subjective experience of "being there" in the virtual environment [32]. Presence comprises both place illusion (the sensation of being in the virtual space) and plausibility (the illusion that events in the space are actually happening) [32]. Higher levels of presence correlate with stronger craving responses, making it a crucial psychological mechanism in VR-based addiction research [31].

Quantitative Evidence: Efficacy of VR in Craving Induction and Reduction

Table 1: Efficacy of VR-Based Interventions Across Substance Use Disorders

| Substance | Study Design | Key Findings | Effect Size/Statistics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methamphetamine | RCT (N=89 men with MUD); CET vs CETA vs NS | Significant reduction in tonic craving post-intervention | CET: p=0.001; CETA: p=0.010; NS: p=0.217 | [30] |

| Methamphetamine | Within-subjects (N=150 men with MUD) | Craving in drug-use scene significantly higher than neutral scenes | p < 0.001 | [29] |

| Alcohol | Single-arm (N=21 AD patients) | Craving significantly higher during and after VR-CE vs before | χ²(2, N=21) = 33.8, p < 0.001 | [31] |

| Various (Review) | Systematic review (7 studies) | VR effective at reducing substance use and cravings in most studies | Mixed results for mood/anxiety outcomes | [33] |

Table 2: Impact of VR on Cognitive and Secondary Outcomes in SUD

| Outcome Domain | Substance | Intervention | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Functioning | Mixed SUD | VR cognitive training (6 weeks) | Significant improvement in experimental group vs control | [34] |

| Drug Refusal Self-Efficacy | Methamphetamine | VR CETA | Significant improvement vs neutral scenes group | [30] |

| Anxiety | Methamphetamine | VR CET | Significant reduction vs neutral scenes group | [30] |

| Treatment Dropout | Mixed SUD | VR cognitive training + TAU | Lower dropout in experimental group (8% vs 27%) | [34] |

| Global Memory | Mixed SUD | VR cognitive training | Significant improvement in visual, auditory, immediate, and delayed recall | [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

VR Cue Exposure Paradigm for Methamphetamine Use Disorder

A comprehensive VR cue exposure paradigm for methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) was developed and validated across multiple studies [30] [29]. The protocol employs a within-subjects design with the following components:

Participant Selection:

- Sample: 150 male participants meeting DSM-5 criteria for MUD [29]

- Inclusion Criteria: Age 18-55, MA use ≥ twice monthly over past two years, minimum six consecutive months of use prior to admission, normal or corrected vision [29]

- Exclusion Criteria: Polysubstance abuse, personal or family history of psychiatric disorders, serious physical illnesses, conditions requiring ongoing medication [29]

VR Environment Development: The paradigm includes five distinct scenes presented in sequence:

- Resting scene (1 minute): Features guiding audio and system logo interface

- Neutral scene 1 (4 minutes): Underwater visuals with ambient water sounds

- MA paraphernalia scene (4 minutes): Displays eight types of MA and related tools (e.g., glass pipes) without audio

- Drug-use scene (4 minutes): Depicts social context of MA use (e.g., two men and two women using MA while playing cards in a game room) with professional actors, dynamic contextual cues, special effects, and audio including prompt, "Do you want a hit?"

- Neutral scene 2 (4 minutes): Elephant-walking grassland scene with natural sounds [30] [29]

Assessment Protocol:

- Tonic Craving: Measured using Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ranging from 1 (no craving) to 10 (strongest craving) during withdrawal period

- Cue-Induced Craving: Assessed using VAS within VR environment after exposure to each scene type

- Clinical Measures: Methamphetamine Use Disorder Severity Scale (MUDSS), Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) [29]

Key Findings:

- Craving in drug-use scene was significantly higher than in neutral and paraphernalia scenes (p < 0.001)

- Cue-induced craving was significantly higher than pre-exposure withdrawal craving (p < 0.05)

- Withdrawal craving scores positively correlated with craving scores in all three VR scenarios (p < 0.01) [29]

VR-Based Cue Exposure with Aversion Therapy

A randomized controlled trial implemented an advanced protocol combining cue exposure with aversion therapy for MUD [30]:

Study Design:

- Participants: 89 men with MUD randomly assigned to CET (n=30), CETA (n=29), or neutral scenes (NS, n=30)

- Intervention Duration: 16 sessions over 8 weeks

CETA Protocol:

- Cue Exposure Component: Similar to the basic paradigm described above

- Aversion Component: Following exposure to drug cues, participants were exposed to aversive stimuli (e.g., unpleasant odors, images of negative consequences) to create negative associations with substance-related cues

- Theoretical Basis: Counter-conditioning approach creating opposing associations to weaken drug cue salience [30]

Outcome Measures:

- Primary Outcomes: Tonic craving and cue-induced craving

- Secondary Outcomes: Attentional bias, rehabilitation confidence, drug refusal self-efficacy, anxiety (GAD-7), and depression (PHQ-9)

Key Findings:

- Both CET and CETA groups demonstrated significant reductions in tonic craving post-intervention (CET: p=0.001; CETA: p=0.010)

- CET group showed significantly lower post-intervention tonic craving compared to NS group (p=0.047)

- CETA group showed significantly improved drug refusal self-efficacy compared to baseline (p=0.001) and NS group (p=0.018)

- CET group demonstrated reduced anxiety compared to NS group (p=0.014) [30]

Visualization of Neurobiological Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Neurobiological Pathways and Experimental Workflow of VR-Induced Craving

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Addiction Studies

| Component Category | Specific Tools/Measures | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) with tracking systems | Creates immersive 3D environments that respond to user movement | HTC Vive, Oculus Rift [32] |