Validating Brain Signatures: A Roadmap for Reproducible Models in Neuroscience and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for ensuring the replicability of brain signature models across independent validation datasets, a critical challenge in neuroscience and clinical translation.

Validating Brain Signatures: A Roadmap for Reproducible Models in Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for ensuring the replicability of brain signature models across independent validation datasets, a critical challenge in neuroscience and clinical translation. We explore the foundational principles of data-driven brain signatures and their evolution from theory-driven approaches. The piece details rigorous methodological frameworks for development and validation, including multi-cohort discovery and aggregation techniques. It addresses key troubleshooting strategies for overcoming sources of irreproducibility, from dataset limitations to computational variability. Finally, we present systematic validation approaches and comparative analyses demonstrating how replicated signatures outperform traditional biomarkers in clinical applications and drug development contexts, offering researchers and pharmaceutical professionals practical guidance for building robust, translatable brain biomarkers.

The Foundation of Brain Signatures: From Theoretical Concepts to Data-Driven Discovery

The quest to define robust brain signatures represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, moving from theory-driven hypotheses to data-driven explorations of brain-behavior relationships. These signatures, often derived as statistical regions of interest (sROIs), aim to identify key brain regions most associated with specific cognitive functions or clinical conditions. This review objectively compares the performance of emerging signature methodologies against traditional approaches, with particular emphasis on their replicability across validation datasets. We synthesize experimental data from recent validation studies, provide detailed methodologies for key experiments, and evaluate the comparative explanatory power of different modeling frameworks. The evidence indicates that validated signature models consistently outperform traditional theory-based models in explanatory power when rigorously tested across multiple cohorts, establishing their growing significance for clinical applications and drug development.

The "brain signature of cognition" concept has garnered significant interest as a data-driven, exploratory approach to better understand key brain regions involved in specific cognitive functions [1]. These signatures, alternatively termed "statistical regions of interest" (sROIs or statROIs) or "signature regions," are identified through systematic analysis of brain imaging data to discover areas most strongly associated with behavioral outcomes or clinical conditions [1]. This approach marks an evolution from traditional theory-driven or lesion-driven approaches that dominated earlier research [1].

The fundamental challenge in brain signature research lies in establishing replicability across validation datasets—a signature developed in one discovery cohort must demonstrate consistent model fit and spatial selection when applied to independent populations [1]. Without such validation, signatures may reflect cohort-specific characteristics rather than generalizable brain-behavior relationships. This review examines the methodological frameworks for defining and validating these signatures, compares their performance against alternative approaches, and assesses their emerging clinical significance for disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment.

Methodological Frameworks: Comparing Signature Identification Approaches

Signature Identification Pipelines

Different methodological frameworks have emerged for identifying brain signatures, each with distinct advantages and validation requirements. The table below compares two prominent approaches from recent literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Brain Signature Identification Methods

| Method Characteristic | Consensus Gray Matter Signature Approach [1] | Network-Based Signature Identification [2] |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | Structural MRI (gray matter thickness) | Structural MRI (gray matter tissue probability maps) |

| Feature Selection | Voxel-based regressions with consensus masking | Sorensen distance between probability distributions |

| Analytical Framework | Data-driven exploratory region identification | Brain network construction with condition-related features |

| Validation Approach | Multi-cohort replication of model fits | Examination subject classification accuracy |

| Key Advantages | Does not require predefined ROIs; fine-grained spatial resolution | Provides network neuroscience perspective; individual subject analysis |

| Clinical Applications | Episodic memory; everyday memory function | Alzheimer's disease; mild cognitive impairment classification |

Traditional Versus Signature Approaches

The signature approach addresses several limitations of traditional methods. Theory-driven approaches based on predefined regions of interest (ROIs) may miss subtler effects that cross traditional anatomical boundaries [1]. Similarly, methods using predefined brain atlas regions cannot optimally fit behavioral outcomes when associations recruit subsets of multiple regions without using the entirety of any single region [1].

Machine learning implementations of signature identification—including support vector machines, support vector classification, relevant vector regression, and convolutional neural nets—offer promising alternatives, particularly for investigating complex multimodal brain associations [1]. However, these often face interpretability challenges, functioning as "black box" systems that can be difficult to translate to clinical applications [1].

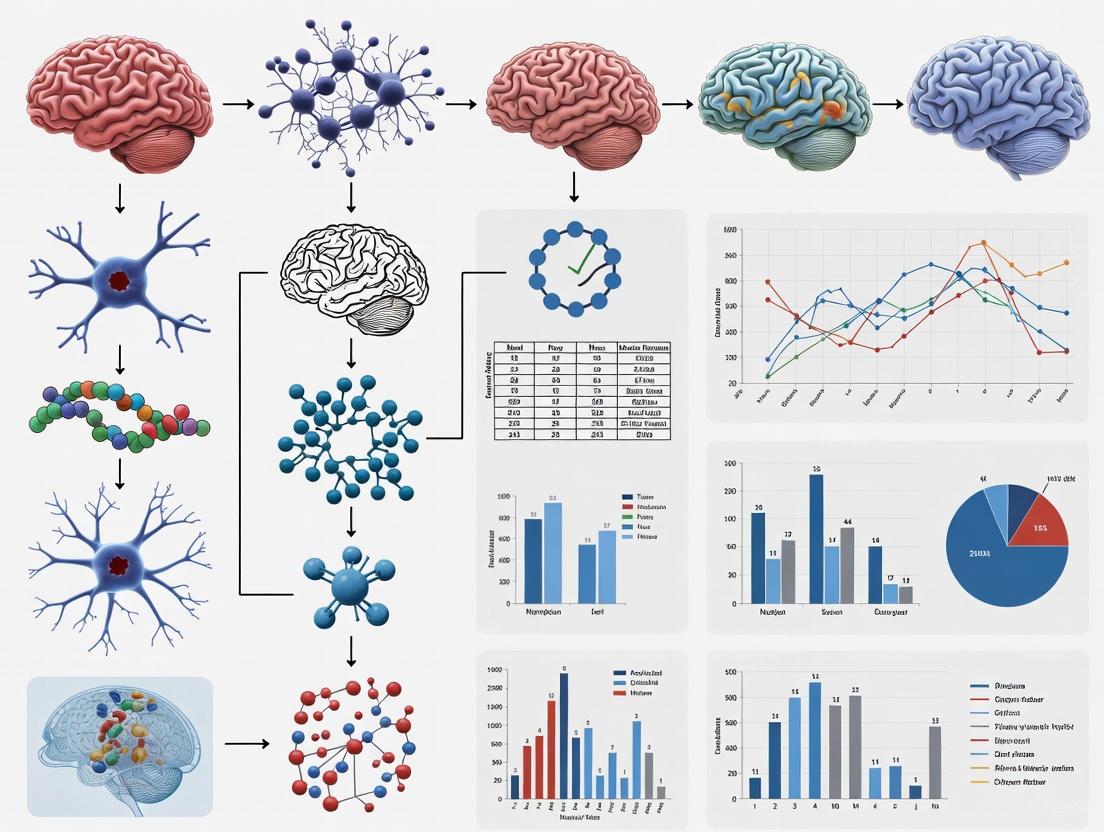

Figure 1: Methodological comparison between traditional and signature-based approaches for brain region identification

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Multi-Cohort Consensus Signature Protocol

A rigorous validation study published in 2023 established a protocol for developing robust brain signatures with demonstrated replicability [1]. The methodology proceeded through these stages:

Discovery Phase: Researchers derived regional brain gray matter thickness associations for neuropsychological and everyday cognition memory domains in two discovery cohorts (578 participants from UC Davis Alzheimer's Disease Research Center and 831 participants from Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Phase 3) [1].

Consensus Identification: The team computed regional associations to outcome in 40 randomly selected discovery subsets of size 400 in each cohort. They generated spatial overlap frequency maps and defined high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1].

Validation Framework: Using separate validation datasets (348 participants from UCD and 435 participants from ADNI Phase 1), researchers evaluated replicability of cohort-based consensus model fits and explanatory power by comparing signature model fits with each other and with competing theory-based models [1].

This protocol specifically addressed the pitfall of using discovery sets that are too small, which can lead to inflated strengths of associations and loss of reproducibility [1]. The approach leveraged multi-cohort discovery and validation to produce signature models that replicated model fits to outcome and outperformed other commonly used measures [1].

Network-Based Signature Identification Protocol

An alternative methodology for structural MRI-based signature identification employs brain network construction followed by signature extraction [2]:

Image Processing: Structural T1 MRI images undergo brain extraction using FreeSurfer, transformation to MNI standard space, segmentation into gray matter tissue probability maps (TPMs), and smoothing [2].

Network Construction: Brain networks are constructed using atlas-based regions as nodes and Sorensen distance between probability distributions of gray matter TPMs as edges, creating an individual brain network for each subject [2].

Signature Extraction: Condition-related brain signatures are identified by comparing disorder networks (MCI, PMCI, AD) to those of normal control subjects, extracting distinctive network patterns that differentiate clinical conditions [2].

Validation: Examination subjects (200 total: 50 each of control, MCI, PMCI, and AD) are used to evaluate classification performance based on the identified signature patterns [2].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for multi-cohort brain signature validation

Performance Comparison: Signature Models Versus Alternatives

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The critical test for any brain signature methodology is its performance in validation cohorts compared to established approaches. Recent research provides direct comparative data:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Brain Signature Models Against Traditional Approaches

| Model Type | Replicability Rate | Spatial Consistency | Explanatory Power | Validation Cohort Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Signature Models [1] | High replicability (highly correlated fits in 50 validation subsets) | Convergent consensus regions across cohorts | Outperformed other models in full cohort comparisons | Maintained performance across independent validation datasets |

| Theory-Based Models [1] | Variable replicability | Dependent on theoretical assumptions | Lower explanatory power than signature models | Inconsistent performance across cohorts |

| Network-Based Signatures [2] | Effective classification of examination subjects | Identified condition-specific networks | Successfully differentiated MCI, PMCI, and AD | Applied to 200 examination subjects with demonstrated efficacy |

| Machine Learning Approaches [1] | Requires large datasets (1000s of participants) | Potential interpretability challenges | Handles complex multimodal associations | Black box characteristics may limit clinical translation |

Replicability Across Cohorts

The consensus signature approach demonstrated particularly strong replicability characteristics. When signature models developed in two discovery cohorts were applied to 50 random subsets of each validation cohort, the model fits were highly correlated, indicating strong reproducibility [1]. Spatial replications produced convergent consensus signature regions across independent cohorts [1].

This replicability is especially notable given the methodological challenges in brain signature research. Studies have found that replicability depends on large discovery dataset sizes, with some research indicating that sizes in the thousands are needed for certain applications [1]. The consensus approach, using multiple discovery subsets and aggregation, appears to mitigate these requirements while maintaining robustness.

The experimental protocols for brain signature identification rely on specialized tools, datasets, and analytical resources. The following table details key components required for implementing these methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Brain Signature Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Signature Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data | ADNI (Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative) database [1] [2] | Provides standardized, multi-center neuroimaging data for discovery and validation |

| Image Processing | FreeSurfer [2] | Brain extraction, cortical reconstruction, and segmentation |

| Spatial Normalization | FSL (FMRIB Software Library) [2] | Image registration to standard space (MNI) using flirt and fnirt tools |

| Segmentation | FSL-FAST [2] | Tissue segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and CSF probability maps |

| Statistical Analysis | R programming environment [1] | Statistical modeling and implementation of signature algorithms |

| Brain Atlas | Atlas-defined regions (e.g., AAL, Harvard-Oxford) [2] | Provides standardized parcellation for network node definition |

| Validation Framework | Multiple independent cohorts [1] | Enables rigorous testing of signature replicability and generalizability |

Clinical Significance and Applications

Diagnostic and Classification Applications

Brain signatures show particular promise for improving diagnosis and classification of neurological and psychiatric disorders. The network-based signature approach demonstrated effective classification of Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and progressive MCI using structural MRI data [2]. This classification capability has direct clinical relevance for early detection and differential diagnosis.

The signature framework also enables investigation of shared neural substrates across different behavioral domains. Research comparing signatures in two memory domains (neuropsychological and everyday memory) suggested strongly shared brain substrates, providing insights into the neural architecture of memory function [1].

Biomarker Development for Therapeutic Interventions

For drug development professionals, brain signatures offer potential intermediate biomarkers for tracking treatment response and target engagement. The robust, replicable nature of properly validated signatures makes them candidates for inclusion in clinical trials as objective measures of brain changes associated with therapeutic interventions.

The ability of signature approaches to detect subtle, distributed brain changes—rather than focusing only on obvious, localized atrophy—may provide more sensitive measures of treatment effects, particularly in early stages of neurodegenerative disease when interventions are most likely to be effective.

The validation of brain signatures as robust measures of behavioral substrates represents significant progress toward clinically useful biomarkers. The comparative evidence indicates that data-driven signature approaches, particularly those implementing rigorous multi-cohort validation, outperform traditional theory-based models in explanatory power and replicability.

The consensus signature methodology, with its demonstrated replicability across validation datasets, and network-based approaches, with their individual subject classification capabilities, offer complementary strengths for different clinical and research applications. As these methods continue to be refined and validated across increasingly diverse populations, they hold promise for advancing both our understanding of brain-behavior relationships and our ability to detect and monitor neurological disorders.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the emerging best practice emphasizes signature development in large, diverse cohorts with deliberate investment in independent validation. This approach, while resource-intensive, produces the robust, generalizable signatures needed for meaningful clinical application.

The Evolution from Theory-Driven to Data-Driven Exploratory Approaches

The field of cognitive neuroscience is undergoing a profound methodological shift, moving from traditional, hypothesis-driven studies to robust, data-driven exploratory approaches. This evolution is critical for developing brain signature models—multivariate patterns derived from neuroimaging data that quantify individual differences in brain health and behavior. Central to this paradigm shift is the pressing challenge of replicability, the ability of a model's performance to generalize across independent validation datasets. This guide objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches and brain features, providing experimental data and detailed protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their study design and analytical choices.

Traditional theory-driven research in neuroscience often begins with a specific hypothesis, typically employing mass-univariate analyses (e.g., t-tests on pre-defined brain regions) to test it. While valuable, this approach can be underpowered to detect the subtle, distributed brain-behavior relationships that characterize complex neuropsychiatric conditions and cognitive traits. The reliance on small sample sizes and single studies has led to a replicability crisis, where many published brain-wide association studies (BWAS) fail to generalize [3].

The emergence of data-driven exploratory approaches, powered by machine learning (ML) and large, collaborative, multinational datasets, offers a solution. These methods, such as the SPARE (Spatial Patterns of Abnormalities for Recognition of Early Brain Changes) framework, leverage multivariate patterns across the entire brain to create individualized indices of disease severity or behavioral traits [4]. This guide compares these two paradigms through the lens of replicability, providing a foundational resource for building more reliable and generalizable neuroimaging biomarkers.

Comparative Performance of Modeling Approaches

The core of this evolution lies in the superior performance of multivariate, data-driven models over conventional mass-univariate or theory-driven methods, particularly when it comes to replicability and effect size.

Table 1: Comparison of Theory-Driven vs. Data-Driven Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Theory-Driven (Mass-Univariate) | Data-Driven (Multivariate ML) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Tests hypotheses in pre-specified regions of interest (ROIs). | Discovers patterns from the whole brain without strong a priori assumptions. |

| Typical Sample Size | Often limited (n < 100), leading to low statistical power. | Leverages large samples (n > 10,000), enhancing power and generalizability [4]. |

| Replicability | Often low, as effects are small and sample-dependent. | Significantly higher, especially for stable, trait-like phenotypes [3]. |

| Effect Size | Small, explaining a low percentage of phenotypic variance. | Can achieve a ten-fold increase in effect sizes compared to conventional MRI markers [4]. |

| Individual-Level Prediction | Limited; focused on group-level differences. | Excellent; provides personalized severity scores for individual patients [4]. |

| Handling Comorbidities | Difficult to disentangle multiple overlapping conditions. | Can quantify the specific signature of individual conditions even when they co-occur [4]. |

Supporting Experimental Data on Replicability

A comprehensive 2025 study systematically evaluated the replicability of diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI)-based brain-behavior models, providing crucial benchmarks for the field [3]. The findings underscore the relationship between methodology, sample size, and replicability.

Table 2: Replicability of DWI-Based Multivariate Models for Brain-Behavior Associations (HCP Dataset, n ≤ 425) [3]

| DWI Metric | Overall Phenotypes Replicable | Trait-Like Phenotypes Replicable | State-Like Phenotypes Replicable | Avg. Discovery Sample Needed (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streamline Count (SC) | 29% | 42% | 19% | 171 |

| Fractional Anisotropy (FA) | ~28%* | ~50%* | ~19%* | >200 |

| Radial Diffusivity (RD) | ~28%* | ~50%* | ~19%* | >250 |

| Axial Diffusivity (AD) | ~28%* | ~50%* | ~19%* | >250 |

| Any DWI Metric | 36% (21/58) | 50% (16/32) | 19% (5/26) | Varies |

Note: Percentages for FA, RD, and AD are approximate averages based on data reported in [3]. The study found that trait-like phenotypes (e.g., crystallized intelligence) were more replicable than state-like ones (e.g., emotional states), and streamline-based connectomes were the most efficient, requiring the smallest sample sizes for replication.

A key finding was the direct relationship between effect size and replicability. Models requiring a discovery sample size larger than n=425 were found to have very small effect sizes, explaining less than 2% of the variance in the phenotype, thus having "limited practical relevance" [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, this section outlines the core methodologies behind the cited data.

Protocol 1: Developing a Data-Driven Brain Signature Model (SPARE Framework)

This protocol is based on the study that developed SPARE models for cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors (CVM) using a large multinational dataset [4].

- Data Acquisition and Harmonization: Collect T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) and FLAIR images from multiple cohort studies (total N = 37,096 in the cited study). Process images through a harmonized pipeline to extract measures of gray matter volume, white matter volume, and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume.

- Ground Truth Labeling: Dichotomize participants into CVM+ (e.g., hypertensive) and CVM- (e.g., normotensive) groups based on clinical criteria, medication use, and established cut-offs for continuous measures.

- Feature Extraction: Parcellate the brain into regions of interest (ROIs) using a standard atlas. Calculate summary measures (e.g., volume, intensity) for each ROI to serve as features for the model.

- Model Training: Train a separate support vector machine (SVM) classifier for each CVM (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) to distinguish between CVM+ and CVM- individuals based on their spatial neuroanatomical patterns.

- Individualized Score Generation: The output of the model is a continuous SPARE-index (e.g., SPARE-HTN) for each participant, which quantifies the expression of that specific CVM's brain signature in the individual.

- Validation: Validate the model's performance on a held-out test set and an entirely independent cohort (e.g., UK Biobank). Assess association with cognitive performance and other biomarkers (e.g., beta-amyloid status) to establish clinical validity.

Protocol 2: Testing Replicability of Structural Connectome Models

This protocol is adapted from the large-scale replicability analysis of DWI-based models [3].

- Phenotype Selection and Categorization: Select a broad range of behavioral and psychometric measures. Categorize them as "trait-like" (enduring, stable) or "state-like" (transient, fluctuating).

- Connectome Construction: Preprocess DWI data. Reconstruct structural connectomes using multiple metrics:

- Streamline Count (SC): Number of white matter streamlines between brain regions.

- Microstructural Metrics: Mean fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), radial diffusivity (RD), and axial diffusivity (AD) along the tracts.

- Model Fitting and Replication Probability Estimation:

- Repeatedly split the dataset into non-overlapping, equally sized discovery and replication sets.

- In the discovery set, fit a multivariate Ridge regression model to predict the phenotype from the connectome features. Use nested cross-validation to avoid overfitting and estimate unbiased effect sizes.

- Test the significance of the established association in the replication set.

- Estimate the probability of replication (Preplication) as the proportion of splits where a significant discovery association also leads to a significant replication.

- Analysis: Determine the minimum discovery sample size required for a Preplication > 0.8. Compare replicability across different DWI metrics and phenotype categories.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Data-Driven Brain Signature Development

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow for developing and validating a data-driven brain signature model, as implemented in the SPARE-CVM study [4].

Replicability Assessment Methodology

This diagram outlines the resampling-based methodology used to empirically evaluate the replicability of brain-phenotype associations [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Replicable Brain Signature Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Multisite MRI Data | Large, diverse datasets (e.g., iSTAGING, UK Biobank, HCP) are fundamental for adequate statistical power and testing generalizability [4]. |

| Harmonized Processing Pipelines | Software (e.g., FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM) configured for consistent image processing across datasets is critical to minimize site- and scanner-specific biases [4]. |

| Structural & Diffusion MRI Sequences | T1-weighted, FLAIR, and diffusion-weighted imaging sequences provide the raw data for quantifying brain structure, lesions, and white matter connectivity [4] [3]. |

| Multivariate Machine Learning Libraries | Software libraries (e.g., scikit-learn in Python) enabling the implementation of models like Support Vector Machines and Ridge Regression are essential for data-driven analysis [4] [3]. |

| Standardized Atlases | Brain parcellation atlases (e.g., AAL, Harvard-Oxford) provide a common coordinate system for extracting ROI-based features from neuroimaging data. |

| Phenotypic Battery | Comprehensive, well-validated behavioral and cognitive tests are needed to define the "phenotype" for brain-behavior association studies [3]. |

In the quest to understand the neural foundations of human behavior, researchers have increasingly turned to data-driven methods to identify brain signatures—multivariate patterns of brain structure or function that reliably predict specific cognitive abilities or behavioral outcomes. The ultimate validation of these signatures lies not in their initial discovery but in their replicability across diverse cohorts and independent datasets. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the experimental approaches and validation outcomes for three key cognitive domains: episodic memory, executive function, and everyday cognition. Each domain presents unique challenges and opportunities for establishing robust, generalizable brain-behavior relationships that can inform clinical practice and therapeutic development.

Comparative Performance of Brain Signature Domains

The table below synthesizes validation performance and neural substrates across the three key brain signature domains, highlighting their relative strengths and replication success.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Brain Signature Domains Across Validation Studies

| Signature Domain | Primary Neural Substrates | Validation Performance | Key Replication Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | Anterior hippocampus (volume, atrophy rate, activation), posterior medial temporal lobe [5] | Superior memory linked to higher retrieval activity in anterior hippocampus (β=0.24-0.28, p<0.001) and less hippocampal atrophy (β=-0.18, p<0.01) [5] | Stable hippocampal correlates across adulthood (age 20-81.5); no significant age interactions found [5] |

| Executive Function | Multiple-demand network (intraparietal sulcus, inferior frontal sulcus, DLPFC, anterior insula) [6] | Low prediction accuracy from resting-state connectivity (R²<0.07, r<0.28); regional gray matter volume most predictive in older adults [6] | Limited replicability for functional connectivity patterns; structural measures outperform functional ones for prediction [6] |

| Everyday Cognition | Distributed gray matter thickness patterns across cortex [7] | Signature models outperformed theory-based models in explanatory power; high replicability in validation cohorts (r>0.9 for model fits) [7] | Spatial replication produced convergent consensus regions; strongly shared substrates with memory domains [7] |

| Cross-Domain Validation | Consensus regions from gray matter thickness [7] | Web-based ECog discriminates CI from CU (AUC=0.722 self-report, 0.818 study-partner) [8] | Web-based assessments valid for remote data collection; comparable to in-clinic measures [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Signature Development and Validation

Multi-Cohort Consensus Signatures for Everyday and Memory Cognition

The most robust validation protocol involves a multi-cohort approach with strict separation between discovery and validation datasets [7]. This method involves:

- Discovery Phase: Deriving regional brain gray matter thickness associations for behavioral domains (neuropsychological and everyday cognition memory) across multiple independent cohorts

- Consensus Mask Generation: Computing regional associations in multiple randomly selected discovery subsets (e.g., 40 subsets of size 400), generating spatial overlap frequency maps, and defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks

- Validation Phase: Evaluating replicability of consensus model fits in completely separate validation datasets using correlation analyses between predicted and observed outcomes

- Comparative Analysis: Testing signature models against competing theory-based models for explanatory power

This protocol successfully identified replicable consensus signature regions with strongly shared brain substrates across memory domains, demonstrating high correlation in validation cohorts (r > 0.9 for model fits) [7].

Multi-Modal Hippocampal Assessment for Episodic Memory

Comprehensive hippocampal profiling provides a robust protocol for episodic memory signature development [5]:

- Structural Imaging: Assessing hippocampal volume through high-resolution T1-weighted MRI

- Longitudinal Atrophy Measurement: Quantifying hippocampal atrophy rates through repeated MRIs (2-7 examinations per participant over up to 9.3 years)

- Microstructural Integrity: Evaluating hippocampal tissue properties via diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)

- Functional Assessment: Measuring encoding and retrieval-related hippocampal activity during fMRI associative memory tasks

- Behavioral Component Analysis: Using principal component analysis of multiple memory variables (correct recognitions, correct rejections, recognition misses, false alarms, recollections) to extract a main component of memory performance

This multi-modal approach revealed that superior memory was associated with higher retrieval activity in the anterior hippocampus and less hippocampal atrophy, with no significant age interactions across adulthood (age 20-81.5 years) [5].

Multi-Metric Predictive Modeling for Executive Function

Given the challenges in predicting executive function, a multi-metric approach provides the most comprehensive assessment [6]:

- Network Definition: Defining executive function networks (EFN) by integrating results from previous neuroimaging meta-analyses, with perceptuo-motor and whole-brain networks as controls

- Multi-Modal Feature Extraction: Calculating gray matter volume (GMV), resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC), regional homogeneity (ReHo), and fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) within these networks

- Prediction Framework Implementation: Applying partial least squares regression (PLSR) to predict individual abilities in three EF subcomponents (inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, working memory) separately for high- and low-demand task conditions

- Age-Stratified Analysis: Conducting separate analyses for young (20-40 years) and older (60-80 years) adults to identify potential age-specific prediction patterns

This protocol revealed that regional GMV carried the strongest information about individual EF differences in older adults, while fALFF did so for younger adults, with overall low prediction accuracies challenging the notion of finding meaningful biomarkers for individual EF performance with current metrics [6].

Figure 1: Multi-cohort validation workflow for robust brain signature development [7].

Signaling Pathways and Neural Workflows

Higher-Order Brain Dynamics for Individual Identification

Advanced analytical approaches are revealing higher-order organization in brain function that may provide more robust signatures:

- Topological Feature Extraction: Applying persistent homology to fMRI time-series data to capture intrinsic shape properties of brain dynamics through connected components, loops, and voids [9]

- Higher-Order Interaction Mapping: Using simplicial complexes to model interactions between three or more brain regions simultaneously, moving beyond traditional pairwise connectivity [10]

- Temporal Dynamics Characterization: Employing delay embedding to reconstruct one-dimensional time series into high-dimensional state spaces, capturing non-linear dynamical features [9]

These approaches have demonstrated superior performance in both gender classification and behavioral prediction tasks compared to conventional temporal feature metrics, highlighting the advantage of topological approaches in capturing individualized brain dynamics [9].

Figure 2: Higher-order and topological analysis frameworks for brain signatures [9] [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Brain Signature Development and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Measures | Research Applications | Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Assessments | Everyday Cognition (ECog) scale [8], Associative memory fMRI tasks [5], Executive function battery (inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility) [6] | Self- and informant-report of daily functioning, Laboratory-based cognitive challenge, Multi-component cognitive assessment | Web-based ECog discriminates CI from CU (AUC=0.722-0.818) [8], Hippocampal activation predicts memory performance [5] |

| Neuroimaging Modalities | Structural MRI (gray matter thickness, volume) [7] [5], Resting-state fMRI (functional connectivity) [6], Diffusion Tensor Imaging (microstructural integrity) [5] | Brain structural assessment, Functional network characterization, White matter integrity measurement | Gray matter thickness signatures show high replicability [7], DTI measures correlate with memory performance [5] |

| Analytical Approaches | Multi-cohort consensus modeling [7], Topological Data Analysis [9], Higher-order interaction mapping [10], Partial least squares regression [6] | Cross-study validation, Non-linear dynamics characterization, Multi-regional interaction modeling, Multivariate prediction | Outperforms theory-based models [7], Superior to conventional temporal features [9] |

| Validation Frameworks | Separate discovery/validation cohorts [7], Web-based vs. in-clinic comparison [8], Longitudinal atrophy tracking [5] | Replicability assessment, Remote data collection validation, Change over time measurement | High correlation of model fits in validation (r>0.9) [7], Web-based comparable to in-clinic [8] |

The comparative analysis of brain signature domains reveals a critical hierarchy of replicability, with everyday cognition and episodic memory signatures demonstrating more robust validation across cohorts and modalities than executive function signatures. This pattern highlights fundamental challenges in capturing complex, multi-component cognitive processes through current neuroimaging approaches.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings suggest several strategic considerations:

- Signature Selection: Prioritize everyday cognition and episodic memory domains for biomarker development, as these show more consistent neural substrates and better replication across studies

- Methodological Approach: Implement multi-cohort consensus approaches with strict separation between discovery and validation datasets to ensure generalizability

- Modality Choice: Consider structural measures (gray matter volume, thickness) as more reliable predictors than functional connectivity, particularly for executive functions

- Technological Innovation: Leverage emerging higher-order and topological analysis methods that show promise for capturing more nuanced brain-behavior relationships

The limited replicability of executive function signatures, particularly those based on functional connectivity, underscores the need for more sophisticated analytical frameworks and multi-modal approaches that can capture the complexity of this cognitive domain. As the field advances, the integration of topological methods and higher-order interaction mapping may provide the necessary breakthrough to establish robust, replicable brain signatures across all major cognitive domains.

The growing recognition of a replication crisis has affected numerous scientific fields, challenging the credibility of empirical results that fail to reproduce in subsequent studies [11]. In neuroimaging and brain signature research, this crisis manifests as an inability to reproduce brain-behavior associations across different datasets and populations, undermining the potential for developing reliable biomarkers for neurological and psychiatric conditions [12]. The replication crisis is frequently discussed in psychology and medicine, where considerable efforts have been undertaken to reinvestigate classic studies, though substantial evidence indicates other natural and social sciences are similarly affected [11].

The paradigm in human neuroimaging research has shifted from traditional brain mapping approaches toward developing multivariate predictive models that integrate information distributed across multiple brain systems [13]. This evolution from mapping local effects to building integrated brain models of mental events represents a fundamental change in how researchers approach brain-behavior relationships. While traditional approaches analyze brain-mind associations within isolated brain regions, multivariate brain models specify how to combine brain measurements to yield predictions about mental processes [13]. This shift in methodology has highlighted the critical importance of establishing replicable brain signatures that can reliably predict behavioral and cognitive outcomes across independent validation cohorts.

Quantitative Comparison of Replicability Across Neuroimaging Approaches

Performance Metrics for Brain Signature Replicability

Table 1: Replicability Rates Across Different Neuroimaging Modalities and Phenotypes

| Modality/Phenotype Category | Replicability Rate | Average Sample Size Required | Key Factors Influencing Replicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DWI-based multivariate BWAS (Overall) | 36% (21/58 phenotypes) | Variable (n ≤ 425) | Effect size, phenotype type, DWI metric [12] |

| DWI Streamline Connectomes (SC) | 29% (HCP), 42% (AOMIC) | n = 171 (average) | Most economic metric for sample size requirements [12] |

| DWI for Trait-like Phenotypes | 50% (16/32) | n = 150 (average) | Temporal stability, enduring characteristics [12] |

| DWI for State-like Phenotypes | 19% (5/26) | n = 325 (average) | Transient, fluctuating characteristics [12] |

| Gray Matter Signature Models | High replicability reported | n = 400 (discovery) | Consensus signature masks, multiple discovery subsets [1] |

| Rigorous Research Practices | ~90% (16 studies) | Not specified | Preregistration, large samples, confirmation tests [14] |

Effect Size and Sample Size Relationships

Table 2: Effect Size and Sample Size Requirements for Replicable Brain Signatures

| Effect Size Threshold | Discovery Sample Required | Replicability Probability | Practical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| <2% variance explained | n > 400 | Low | Limited practical relevance [12] |

| ~5% variance explained | n < 300 | High | Good replicability potential [12] |

| >5% variance explained | n < 300 | High | Strong practical utility [12] |

| Small effect sizes | n > 425 | Preplication > 0.8 | Requires large sample sizes [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Brain Signatures

Signature Derivation and Consensus Mask Generation

The validation of brain signatures requires rigorous methodologies that can withstand the challenges of replicability across diverse cohorts. One prominent approach involves deriving regional brain gray matter thickness associations for specific behavioral domains across multiple discovery cohorts [1]. The protocol involves:

Multiple Discovery Subsets: Researchers compute regional associations to outcomes in 40 randomly selected discovery subsets of size 400 in each cohort [1]. This multiple-subset approach helps overcome the pitfalls of single discovery sets and produces more reproducible signatures.

Spatial Overlap Frequency Maps: The method generates spatial overlap frequency maps from these multiple discovery iterations, defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1]. This consensus approach leverages aggregation across many randomly selected subsets to produce robust brain phenotype measures.

Independent Validation: Using separate validation datasets completely distinct from discovery cohorts, researchers evaluate replicability of cohort-based consensus model fits and explanatory power by comparing signature model fits with each other and with competing theory-based models [1].

Multivariate Predictive Modeling with DWI Data

For DWI-based brain-behavior models, a systematic protocol has been developed to assess replicability:

Dataset Splitting: The methodology involves repeatedly sampling non-overlapping, equally sized discovery and replication sets, testing significance of established associations in both [12].

Model Training: In the discovery phase, researchers fit Ridge regression models with optimal regularization parameters estimated in a nested cross-validation framework to avoid biased estimates [12].

Replication Probability Threshold: Studies use a replication probability threshold of Preplication > 0.8, meaning the identified brain-phenotype association has a probability greater than 80% to be significant (p < 0.05) in the replication study, given it was significant in the discovery dataset [12].

Effect Size Comparison: Beyond significance testing, the protocol investigates how well the magnitude of effect sizes replicates, providing an approach independent of arbitrary significance thresholds [12].

Brain Signature Validation Workflow

Enhancing Replicability Through Rigorous Research Practices

Methodological Rigor in Study Design

Evidence strongly indicates that implementing rigor-enhancing practices can dramatically improve replication rates. A multi-university study found that when four key practices were implemented, replication rates reached nearly 90%, compared to the 50% or lower rates commonly reported in many fields [14]. These practices include:

Confirmatory Tests: Researchers should run confirmatory tests on their own studies to corroborate results prior to publication [14].

Adequate Sample Sizes: Data must be collected from sufficiently large sample sizes to ensure adequate statistical power [14].

Preregistration: Scientists should preregister all studies, committing to hypotheses and methods before data collection to guard against p-hacking [14].

Comprehensive Documentation: Researchers must fully document procedures to ensure peers can precisely repeat them [14].

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Several advanced analytical frameworks have been developed specifically to enhance replicability in neuroimaging research:

NeuroMark Framework: This fully automated spatially constrained independent component analysis (ICA) framework uses templates combined with data-driven methods for biomarker extraction [15]. The approach has been successfully applied in numerous studies, identifying brain markers reproducible across datasets and disorders.

Whole MILC Architecture: A deep learning framework that learns from high-dimensional dynamical data while maintaining stable, ecologically valid interpretations [16]. This architecture includes self-supervised pretraining to maximize "mutual information local to context," capturing valuable knowledge from data not directly related to the study.

Retain And Retrain (RAR) Validation: A method to validate that biomarkers identified as explanations behind model predictions capture the essence of disorder-specific brain dynamics [16]. This approach uses an independent classifier to verify the discriminative power of salient data regions identified by the primary model.

Factors Influencing Replicability

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Replicable Brain Signature Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| NeuroMark Framework | Automated spatially constrained ICA | Biomarker extraction reproducible across datasets and disorders [15] |

| Consensus Signature Masks | Define high-frequency brain regions | Aggregate results across multiple discovery subsets [1] |

| Ridge Regression Models | Multivariate predictive modeling | Establish brain-phenotype associations with regularization [12] |

| Structural Connectomes | Map neural pathways | DWI-based streamline count models for highest replicability [12] |

| Higher-Resolution Atlases | Brain parcellation | Improve replicability (e.g., 162-node Destrieux vs. 84-region Desikan-Killiany) [12] |

| Preregistration Protocols | Study design specification | Guard against p-hacking and selective reporting [14] |

| Mutual Information Local to Context (MILC) | Self-supervised pretraining | Capture valuable knowledge from data not directly related to study [16] |

The critical importance of replicability in brain signature research extends from initial discovery sets through independent validation cohorts. The evidence consistently demonstrates that robust brain signatures are achievable when studies implement rigorous methodology, adequate sample sizes, and appropriate analytical frameworks. The replication rates of nearly 90% achieved through rigorous practices compared to the 50% or lower rates in many published studies highlight the potential for improvement across neuroimaging research [14].

The findings from multiple large-scale studies suggest several key principles for enhancing replicability. First, trait-like phenotypes show substantially higher replicability (50%) compared to state-like measures (19%), informing appropriate target selection for biomarker development [12]. Second, effect size remains a crucial factor, with associations explaining less than 2% of variance requiring sample sizes exceeding 400 participants and offering limited practical relevance [12]. Third, multivariate approaches that leverage distributed brain patterns consistently outperform isolated region analyses, reflecting the population coding principles fundamental to neural computation [13].

As the field progresses, the development of standardized frameworks like NeuroMark that combine templates with data-driven methods and the adoption of rigorous practices including preregistration and independent validation will be essential for establishing brain signatures that reliably translate across diverse populations and clinical applications. Only through such rigorous attention to replicability can brain signature research fulfill its potential to advance understanding of brain function and dysfunction.

The identification of robust and replicable neural signatures represents a paramount challenge in modern neuroscience, particularly for applications in psychiatric drug development. The concept of a "brain signature" refers to a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions most associated with specific cognitive functions or behavioral domains [1]. Unlike traditional hypothesis-driven methods that focus on predefined regions of interest, signature-based approaches leverage large datasets and statistical methods to discover brain-behavior relationships that might otherwise remain obscured [1]. The critical test for any proposed neural signature lies in its replicability across independent validation cohorts—a standard that ensures findings are not mere artifacts of a particular sample but reflect fundamental neurobiological principles [1] [17]. This review synthesizes current evidence for shared neural substrates across behavioral domains, examining the convergence of brain network engagement with a specific focus on methodological rigor and translational potential.

Fundamental Brain Networks as Convergent Hubs

Converging evidence from multiple cognitive domains indicates that large-scale brain networks serve as common computational hubs, reconfigured in domain-specific patterns to support diverse behaviors. Research on creativity and aesthetic experience has delineated how core networks—including the default mode network (DMN), executive control network (ECN), salience network (SN), sensorimotor network (SMN), and reward system (RS)—orchestrate complex cognitive processes through dynamic interactions [18]. These networks demonstrate remarkable functional versatility, participating in both seemingly disparate and intimately related behavioral domains.

Table 1: Core Brain Networks and Their Cross-Domain Functions

| Brain Network | Key Regions | Functions in Creative Process | Functions in Other Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Hippocampus, Precuneus, mPFC, PCC, TPJ | Memory retrieval, spontaneous divergent thinking, affective evaluation [18] | Self-referential processing, theory-of-mind [18] |

| Executive Control Network (ECN) | Lateral PFC, Posterior Parietal Cortex | Inhibiting conventional ideas, mental set shifting, novel association formation [18] | Analytical reasoning, cognitive control [18] |

| Salience Network (SN) | Anterior Insula, Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Monitoring novel/emotional features, modulating DMN-ECN coupling [18] | Interoceptive awareness, attention to salient stimuli [18] |

| Sensorimotor Network (SMN) | Precentral & Postcentral Gyri, Supplementary Motor Area | Enhancing creative output, improvisational capability [18] | Motor execution, sensory processing [18] |

| Reward System (RS) | Ventral Striatum, Ventromedial PFC | Reinforcing creative behavior through dopamine-mediated pleasure [18] | Processing rewards, valuation, motivation [18] |

The DMN demonstrates particularly broad involvement across domains. During aesthetic experience, the DMN supports memory retrieval and spontaneous divergent thinking when individuals engage with aesthetic stimuli [18]. Similarly, in decision-making contexts, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)—a key DMN node—shows reduced activity in individuals less susceptible to framing biases, suggesting its role in integrating emotional context with decision values [19]. This pattern of network reuse extends to the ECN, which remains suppressed during creative generation to enable intuitive thinking but becomes activated during creative evaluation to inhibit conventional ideas and facilitate novel associations [18].

Domain-Specific Modulations Within Shared Networks

While fundamental networks provide common infrastructure, domain-specific challenges recruit specialized modulations within these shared systems. The framing effect in decision-making—where choices are influenced by whether options are presented as gains or losses—reveals how similar cognitive biases can emerge from distinct neural substrates depending on context [19].

Table 2: Domain-Specific Neural Substrates of the Framing Effect

| Experimental Domain | Key Task Characteristics | Primary Neural Substrate | Supporting Connectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain Domain | Decisions about potential gains; "keep" vs. "lose" frames [19] | Amygdala [19] | Amygdala-vmPFC connectivity modulated by framing bias [19] |

| Loss Domain | Decisions about potential losses; "save" vs. "still lose" frames [19] | Striatum [19] | Striatum-dmPFC connectivity modulated by framing bias [19] |

| Aversive Domain (Asian Disease Problem) | Vignette-based scenarios in loss domain [19] | Right inferior frontal gyrus, anterior insula [19] | Not specified in search results |

Neuroimaging studies using gambling tasks have demonstrated that the amygdala specifically represents the framing effect in the gain domain, while the striatum underlies the same effect in the loss domain, despite producing behaviorally similar bias patterns [19]. This domain-specific specialization within the broader cortical-striatal-limbic network highlights how shared computational challenges—such as incorporating emotional context into decisions—may be solved by different neural systems depending on the nature of the emotional valence (appetitive versus avversive) [19].

The stability of neural signatures is further evidenced by research on lifespan adversity, which has identified a widespread morphometric signature that persists into adulthood and replicates across independent cohorts [17]. This signature extends beyond traditionally investigated limbic regions to include the thalamus, middle and superior frontal gyri, occipital gyrus, and precentral gyrus [17]. Different adversity types produce partially distinct morphological patterns, with psychosocial risks showing the highest overlap and prenatal exposures demonstrating more unique signatures [17].

Diagram 1: Dynamic network reconfiguration across creative stages, showing suppression of ECN during generation and synergistic engagement during evaluation.

Methodological Framework for Signature Validation

The establishment of replicable brain signatures requires rigorous methodological standards and validation procedures. The signature approach represents an evolution from theory-driven methods, leveraging comprehensive brain parcellation atlases and data-driven feature selection to identify combinations of brain regions that best associate with behaviors of interest [1]. Key considerations for robust signature development include:

Discovery and Validation Protocols

Statistical validation of brain signatures necessitates a structured approach to ensure generalizability beyond the initial discovery cohort. Fletcher et al. (2023) outline a method wherein regional gray matter thickness associations are computed for specific behavioral domains across multiple randomly selected discovery subsets [1]. High-frequency regions across these subsets are defined as "consensus" signature masks, which are then evaluated in separate validation datasets for replicability of model fits and explanatory power [1]. This method has demonstrated that signature models can outperform other commonly used measures when rigorously validated [1].

Critical to this process is the use of sufficiently large discovery sets, with recent research indicating that sample sizes in the thousands may be necessary for optimal replicability [1]. Pitfalls of undersized discovery sets include inflated association strengths and poor reproducibility—challenges that large-scale initiatives like the UK Biobank are now addressing [1]. Furthermore, cohort heterogeneity encompassing the full range of variability in brain pathology and cognitive function enhances the generalizability of resulting signatures [1].

Normative Modeling of Individual Variation

Normative modeling approaches offer a powerful framework for capturing individual neurobiological heterogeneity in relation to environmental factors such as lifespan adversity [17]. This technique involves creating voxel-wise normative models that predict brain structural measures based on adversity profiles, enabling quantification of individual deviations from population expectations [17]. The application of this method has revealed that greater volume contractions relative to the model predict future anxiety symptoms, highlighting the clinical relevance of individual-level predictions [17].

Diagram 2: Statistical validation workflow for brain signatures, emphasizing independent replication in validation cohorts.

Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Signature Investigation

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Signature Validation Research

| Research Component | Specification/Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Packages for Normative Modeling | Enables voxel-wise modeling of individual variation relative to population expectations | SPM, FSL, AFNI with custom normative modeling scripts [17] |

| Multicohort Data Resources | Provides large, diverse samples for discovery and validation phases | UK Biobank, ADNI, MARS, IMAGEN cohorts [1] [17] |

| Cognitive Task Paradigms | Standardized behavioral measures for specific domains | Gambling tasks for framing effects [19], Divergent Thinking Tasks for creativity [18] |

| High-Resolution Structural MRI | Enables voxel-wise morphometric analysis (gray matter thickness, Jacobian determinants) | T1-weighted sequences for deformation-based morphometry [17] |

| Data-Driven Feature Selection Algorithms | Identifies brain-behavior associations without predefined ROI constraints | Support vector machines, relevant vector regression, convolutional neural nets [1] |

Implications for Drug Development and Future Directions

The identification of replicable neural signatures across behavioral domains holds significant promise for psychiatric drug development, particularly in establishing objective biomarkers for target engagement and treatment efficacy evaluation. Shared networks like the DMN, ECN, and SN represent promising intervention targets, as their modulation may transdiagnostically influence multiple cognitive and emotional processes [18] [17]. Furthermore, the documented stability of adversity-related neural signatures into adulthood [17] suggests potential windows for preventive interventions.

Future research directions should prioritize the integration of multimodal imaging data to capture complementary aspects of brain organization, the development of dynamic signature models that track temporal changes in brain-behavior relationships, and the establishment of large-scale collaborative frameworks to ensure sufficient statistical power for robust discovery. As signature validation methodologies continue to advance, they offer the potential to transform neuropsychiatric drug development from symptom-based approaches to those targeting specific, biologically-grounded neural systems.

Methodological Frameworks and Real-World Applications in Research and Drug Development

The replicability of findings across independent validation datasets is a cornerstone of robust scientific discovery, particularly in brain imaging research. The challenge of ensuring that a model or signature derived from one cohort generalizes effectively to another is often mitigated by multi-cohort discovery frameworks. These frameworks frequently employ strategies like random subsampling to efficiently analyze large-scale data and consensus generation to distill stable, reproducible patterns. This guide objectively compares computational tools and algorithms that implement these strategies, focusing on their application in generating consensus masks and signatures from neuroimaging data. Supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies are provided to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate methods for their work.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Key Algorithms

The following tables summarize the core methodologies and quantitative performance of several relevant algorithms that incorporate subsampling and consensus approaches for biological data analysis.

Table 1: Core Algorithm Comparison

| Algorithm | Primary Methodology | Consensus Mechanism | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MILWRM [20] | Top-down, pixel-based spatial clustering using k-means on randomly subsampled data. | Applies a single model, built on a uniform subsample from all samples, to the entire multi-sample dataset. | Spatially resolved omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, multiplex immunofluorescence); consensus tissue domain detection. |

| SpeakEasy2: Champagne (SE2) [21] | Dynamic, popularity-corrected label propagation algorithm with meta-clustering. | Uses a consensus-like approach by initializing with fewer labels than nodes and employing clusters-of-clusters to find robust partitions. | General biological network clustering (gene expression, single-cell, protein interactions); known for robust, informative clusters. |

| BIANCA [22] | Supervised k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) algorithm for automated segmentation. | Performance and output are highly dependent on the composition and representativeness of the training dataset. | Automatic segmentation of white matter lesions (WMLs) in brain MRI; multi-cohort analysis. |

| LPA & LGA [22] | LPA: Pre-trained logistic regression classifier. LGA: Unsupervised lesion growth algorithm. | Do not require training data; their inherent design provides a consistent (consensus) application to any input data. | Automatic segmentation of white matter lesions (WMLs); fast, valid option for specific sub-populations. |

Table 2: Algorithm Performance Benchmarking

| Algorithm / Test Context | Performance Metric | Result | Comparative Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| MILWRM on 37 mIF colon samples [20] | Silhouette-based Confidence Score | Most pixels had high confidence scores. | Successfully identified physiologically relevant tissue domains (epithelium, mucus, lamina propria) across all samples. |

| BIANCA on 1000BRAINS cohort [22] | Dice Similarity Index (DSI) | Mean DSI > 0.7 when trained on diverse data. | Outperformed LPA and LGA when training data included a variety of cohort characteristics (age, cardiovascular risk factors). |

| LPA & LGA on 1000BRAINS cohort [22] | Dice Similarity Index (DSI) | Mean DSI < 0.4 for participants <67 years without risk factors; improved for older participants with risk factors. | Performance was sub-population specific. A less universally reliable option for general multi-cohort studies. |

| SpeakEasy2 (SE2) across diverse synthetic & biological networks [21] | Multiple quality measures (e.g., robustness, scalability) | Generally provided robust, scalable, and informative clusters. | Identified as a strong general-purpose performer across a wide range of applications, though no single method is universally optimal. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

MILWRM Protocol for Consensus Tissue Domain Detection

The MILWRM (Multiplex Image Labeling with Regional Morphology) pipeline provides a clear protocol for consensus discovery using random subsampling, applicable to spatial transcriptomics and multiplex imaging data [20].

- Data Preprocessing: The protocol begins with modality-specific normalization and smoothing. For multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) data, this includes down-sampling images to an isotropic resolution (e.g., 5.6 µm/pixel) and applying a smoothing parameter (sigma=2). The goal is to generalize pixel neighborhood information across batches and samples.

- Random Subsampling: Instead of clustering the entire dataset, which can be computationally intensive and prone to batch effects, MILWRM randomly subsamples a proportion of pixels (e.g., 0.2) uniformly from the tissue mask of each sample. This creates a representative, manageable subset of the entire multi-cohort dataset.

- Consensus Cluster Detection: The subsampled pixel data is Z-normalized, and a k-means model is trained. The number of clusters (k) can be user-specified or determined unsupervisedly via inertia analysis. This model, representing the consensus, is then applied to assign every pixel in the full dataset to a tissue domain.

- Downstream Analysis & Validation: MILWRM calculates domain-specific molecular profiles from the original feature space to biologically annotate the consensus domains. It also computes per-pixel confidence scores based on a modified silhouette score, evaluating how much closer a pixel is to its assigned cluster centroid than to the next closest one [20].

Benchmarking Protocol for White Matter Lesion Segmentation

A critical study compared the performance of three WML segmentation algorithms (BIANCA, LPA, LGA) on the 1000BRAINS cohort, highlighting how algorithm choice and training data affect consensus and generalizability [22].

- Aim 1: Impact of Training Data on Consensus (Using BIANCA): To test how training data composition influences consensus masks, BIANCA was trained multiple times on different subsets of the cohort. Each training set was selected based on a specific characteristic (e.g., only young participants, only hypertensive participants). The output of each model was then compared across the entire test set.

- Aim 2: Cross-Algorithm Performance Benchmarking: The three algorithms were applied to predefined subgroups of participants (e.g., aged under/over 67, with/without cardiovascular risk factors). BIANCA was used with its best-performing training setup from Aim 1.

- Ground Truth and Evaluation: The study relied on the 1000BRAINS cohort, which includes epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory data [22]. Algorithm performance was quantitatively evaluated using the Dice Similarity Index (DSI), measuring the spatial overlap between the algorithm's output and a reference standard.

- Key Findings: BIANCA's WML estimations were directly influenced by the training data, demonstrating that a non-representative "consensus" model can introduce systematic bias (e.g., underestimating WML if trained only on young subjects). Its highest performance was achieved when trained on a diverse group of individuals. In contrast, LPA and LGA, which do not require sample-specific training, showed highly variable performance, working well for older participants with risk factors but poorly for younger, healthier individuals [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the overarching workflow for multi-cohort consensus generation, integrating principles from the analyzed protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Cohort Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Multi-Cohort Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| MILWRM (Python Package) [20] | Consensus tissue domain detection from spatial omics. | Directly implements random subsampling and consensus clustering for multi-sample data from various platforms. |

| SpeakEasy2: Champagne [21] | Robust clustering for diverse biological networks. | Provides a consensus-driven, dynamic clustering algorithm suitable for various data types encountered in multi-cohort studies. |

| BIANCA (FSL Tool) [22] | Supervised WML segmentation from brain MRI. | Highlights the critical importance of training data composition for building generalizable, consensus models. |

| TRACERx-PHLEX (Nextflow Pipeline) [23] | End-to-end analysis of multiplexed imaging data. | Offers a containerized, reproducible workflow for cell segmentation and phenotyping, aiding standardization across studies. |

| 1000BRAINS Cohort Dataset [22] | Population-based brain imaging and epidemiological data. | Serves as a key validation dataset for benchmarking segmentation algorithms and assessing their generalizability. |

| Lancichinetti-Fortunato-Radicchi (LFR) Benchmarks [21] | Synthetic networks with known community structure. | Provides a standardized benchmark for objectively testing and comparing the performance of clustering algorithms. |

The pursuit of replicable and robust biomarkers in neuroscience has led to the emergence of brain signature models as a powerful, data-driven method for identifying key brain regions associated with specific cognitive functions and behavioral outcomes. A significant challenge in this field is ensuring these models maintain performance and explanatory power when applied across diverse datasets, scanners, and populations—a challenge known as the cross-domain problem. Simultaneously, in cryptographic and data security fields, advanced signature aggregation techniques have been developed to efficiently combine multiple distinct signatures into a single, compact representation while preserving verifiability. This guide explores how principles from cryptographic signature aggregation can inform the development of generalized union signatures for brain model domains, focusing on techniques that enhance cross-domain replicability and robustness for research and drug development applications.

Brain Signature Replicability: Foundations and Challenges

The Brain Signature Paradigm in Neuroscience

Brain signatures represent a data-driven, exploratory approach to identify key brain regions most associated with specific behavioral outcomes or cognitive functions. Unlike theory-driven approaches that rely on predefined regions of interest, signature approaches computationally determine areas of the brain that maximally account for brain substrates of behavioral outcomes through statistical region of interest (sROI) identification [1]. This method has evolved from earlier lesion-driven approaches, leveraging high-quality brain parcellation atlases and increased computational power to discover subtle effects that may have been missed by previous methods [1].

The validation of brain signatures requires demonstrating two key properties across multiple datasets beyond the original discovery set: model fit replicability (consistent performance in explaining behavioral outcomes) and spatial extent replicability (consistent identification of signature brain regions across different cohorts) [1]. When properly validated, these signatures serve as reliable brain phenotypes for brain-wide association studies, offering potential applications in diagnosing and tracking neurological conditions and cognitive decline.

The Cross-Domain Challenge in Brain Imaging

Substantial distribution discrepancies among brain imaging datasets from different sources present significant challenges for model replicability. These discrepancies arise from large inter-site variations among different scanners, imaging protocols, and patient populations, leading to what is known as the cross-domain problem in practical applications [24]. Studies have found that replicability depends critically on large discovery dataset sizes, with some research indicating that samples in the thousands are necessary for consistent results [1]. Pitfalls of using insufficient discovery sets include inflated strengths of associations and loss of reproducibility, while cohort heterogeneity—including the full range of variability in brain pathology and cognitive function—also significantly impacts model transferability [1].

Signature Aggregation Techniques: Methodological Approaches

Technical Foundations of Signature Aggregation

Signature aggregation techniques enable multiple signatures, generated by different users on different messages, to be compressed into a single short signature that can be efficiently verified. In formal terms, an aggregate signature scheme consists of four key algorithms: KeyGen (generating public/private key pairs), Sign (producing a signature on a message using a private key), Aggregate (combining multiple signatures into a single compact signature), and Verify (verifying the aggregate against all participants' public keys and messages) [25].

These techniques offer substantial advantages for collaborative environments: verification efficiency through significantly reduced verification time, communication compactness by replacing potentially thousands of individual signatures with a single aggregate, and enhanced scalability through reduced transaction size and storage requirements [25]. Recent advances have focused on privacy-preserving aggregation that prevents identity leakage while maintaining verification integrity.

Cryptographic Implementation Approaches

Table: Comparison of Signature Aggregation Schemes

| Scheme Type | Security Foundation | Privacy Features | Verification Efficiency | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certificateless Aggregate Signature (CLAS) | Discrete Logarithm Problem | Identity Privacy | High (No pairing operations) | Moderate [26] |

| ElGamal-based Aggregate Signatures | Discrete Logarithm Problem | Unlinkable contributions | Moderate | High [25] |

| BLS Aggregate Signatures | Bilinear Pairings | Basic aggregation | High | High [25] |

| Traditional Digital Signatures (ECDSA, RSA) | Various | No privacy protection | Low (Linear verification) | Low |

Several specialized implementation approaches have emerged for specific application domains. For Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs), Lightweight Certificateless Aggregate Signature (CLAS) schemes have been developed that eliminate complex certificate management while providing efficient message aggregation and authentication [26]. Recent research has identified vulnerabilities in some schemes to temporary rogue key attacks, where adversaries can exploit random numbers in signatures to generate ephemeral rogue keys for signature forgery [26]. Security-enhanced approaches incorporate additional aggregator signatures and simultaneous verification to effectively resist such attacks while maintaining computational efficiency.

For privacy-sensitive applications like blockchain-based AI collaboration, ElGamal-based aggregate signature schemes with aggregate public keys enable secure, verifiable, and unlinkable multi-party contributions [25]. These approaches allow multiple AI agents or data providers to jointly sign model updates or decisions, producing a single compact signature that can be publicly verified without revealing identities or individual public keys of contributors—particularly valuable for resource-constrained or privacy-sensitive applications such as federated learning in healthcare or finance [25].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Brain Signature Discovery and Validation Protocol

Table: Experimental Parameters for Brain Signature Validation

| Parameter | Discovery Phase | Validation Phase | Statistical Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 400-800 participants per cohort [1] | 300-400 participants per cohort [1] | Power analysis for effect size detection |

| Data Splitting | 40 randomly selected subsets of size 400 [1] | Completely independent cohorts [1] | Cross-validation metrics |

| Spatial Analysis | Voxel-based regression [1] | Consensus signature mask application [1] | Overlap frequency maps |

| Model Comparison | Comparison with theory-based models [1] | Explanatory power assessment [1] | Fit correlation analysis |

A rigorously validated protocol for brain signature development involves multiple phases. In the discovery phase, researchers derive regional brain gray matter thickness associations for specific domains (e.g., neuropsychological and everyday cognition memory) across multiple discovery cohorts [1]. The process involves computing regional associations to outcome in multiple randomly selected discovery subsets, then generating spatial overlap frequency maps and defining high-frequency regions as "consensus" signature masks [1].

The validation phase uses completely separate validation datasets to evaluate replicability of cohort-based consensus model fits and explanatory power. This involves comparing signature model fits with each other and with competing theory-based models [1]. Performance assessment includes evaluating whether signature models outperform other commonly used measures and examining the degree to which signatures in different domains (e.g., two memory domains) share brain substrates [1].

Diagram Title: Brain Signature Validation Workflow

Cross-Domain Adaptation Experimental Framework

For addressing cross-domain challenges in brain image segmentation, researchers have developed systematic experimental frameworks adhering to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards [24]. The process involves retrieving relevant research from multiple databases using carefully constructed search terms combining three keyword categories: Medical Imaging (e.g., "brain", "MRI", "CT"), Segmentation (e.g., "U-Net", "thresholding", "clustering"), and Domain (e.g., "cross-domain", "multi-site", "harmonization") [24].

The screening and selection process includes merging duplicate articles, screening based on titles and abstracts, and full-text review to filter eligible articles according to inclusion criteria [24]. Data extraction captures author information, publication year, dataset details, cross-domain type, solution method, and evaluation metrics, enabling comparative analysis of method performance across different brain segmentation tasks (stroke lesion segmentation, white matter segmentation, brain tumor segmentation) [24].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Outcomes in Domain Adaptation

Table: Performance Comparison of Domain Adaptation Methods

| Application Domain | Method Category | Performance Metric | Improvement Over Baseline | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke Lesion Segmentation (ATLAS) | Domain-adaptive Methods | Overall accuracy | ~3% improvement [24] | Dataset heterogeneity |

| White Matter Segmentation (MICCAI 2017) | Various Adaptive Methods | Segmentation accuracy | Inconsistent across studies [24] | Lack of unified standards |

| Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) | Normalization Techniques | Cross-domain consistency | Variable performance [24] | Protocol variability |

| Episodic Memory Signature | Consensus Signature Model | Model fit correlation | High replicability [1] | Cohort size dependency |

Domain-adaptive methods have demonstrated measurable improvements in various brain imaging tasks. On the ATLAS dataset, domain-adaptive methods showed an overall improvement of approximately 3 percent in stroke lesion segmentation tasks compared to non-adaptive methods [24]. However, given the diversity of datasets and experimental methodologies in current studies, making direct comparisons of method strengths and weaknesses remains challenging [24].