Validating Brain-Behavior Associations: A Network Framework for Clinical Neuroscience and Drug Development

This article explores the integration of network science to rigorously validate brain-behavior associations in clinical neuroscience.

Validating Brain-Behavior Associations: A Network Framework for Clinical Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the integration of network science to rigorously validate brain-behavior associations in clinical neuroscience. It addresses the critical challenge of linking complex neural data to behavioral outcomes, a central pursuit for researchers and drug development professionals. The content spans from foundational network principles and multi-modal methodologies to troubleshooting design pitfalls and leveraging comparative approaches for robust, translatable findings. By synthesizing these intents, the article provides a comprehensive framework for enhancing the validity of biomarkers, refining animal models, and ultimately accelerating the development of neurological and psychiatric therapeutics.

The Network Approach: Connecting Brain Circuits to Clinical Behavior

Defining Network Science in Clinical Neuroscience and Psychopathology

In recent years, a conceptual shift has occurred in clinical neuroscience and psychopathology, moving from localized, lesion-based models toward a framework that embraces the inherent complexity of brain-behavior relationships. This transformation has been fueled by the emergence of network science, which provides a universal quantitative framework for analyzing complex systems [1]. The promise of this integrated approach lies in a united framework capable of tackling one of the most fundamental questions in science: how to understand the intricate link between brain and behavior [2] [3]. This guide explores how network science principles are redefining our understanding of clinical conditions by mapping the complex webs of interaction between neural structures and behavioral manifestations, offering researchers and drug development professionals new paradigms for diagnostic and therapeutic innovation.

Network science may be succinctly described as "the science of connections" [1]. It employs graphs—abstract mathematical constructs of nodes and connections—to model complex systems ranging from social networks to biological systems [1]. When applied to clinical neuroscience and psychopathology, network science provides powerful tools to move beyond simplistic one-to-one mappings between brain regions and functions, instead embracing the multidimensional, interactive nature of neural systems and their behavioral correlates [2]. This approach has created synergistic opportunities between previously disconnected research fields, enabling the development of more sophisticated models of brain-behavior relationships [3].

Theoretical Foundations: From Brain Modes to Network Models

Historical Evolution of Brain-Behavior Concepts

The theoretical underpinnings of network approaches in clinical neuroscience can be traced to pioneering work that conceptualized regularities in brain-behavior relationships. Anticipating the current network-based transformation, Godefroy and colleagues (1998) proposed four elementary typologies of brain-behaviour relationships termed 'brain modes' (unicity, equivalence, association, summation) as building blocks to describe associations between intact or lesioned brain regions and cognitive processes or neurological deficits [4]. This framework represented one of the earliest attempts to conceptualize neurological symptoms as emerging from interactions between multiple anatomical structures organized in networks, rather than from models emphasizing individual regional contributions [4].

The original brain modes framework has since been expanded and refined in the new computational era, with the addition of a fifth mode (mutual inhibition/masking summation) to better account for the full spectrum of observed clinical phenomena [4]. This theoretical evolution reflects the growing recognition that connectional (hodological) systems perspectives are essential for formulating cognition as subserved by hierarchically organized interactive brain networks [4].

The Network Approach to Psychopathology

In parallel developments within psychopathology, network approaches have emerged as alternatives to traditional latent variable models of mental disorders. Rather than conceiving symptoms as manifestations of underlying disorders, network perspectives conceptualize mental disorders as causal systems of mutually reinforcing symptoms [2] [3]. This paradigm shift has profound implications for understanding the dynamic interplay between biological substrates and psychological phenomena, suggesting that psychopathology may emerge from feedback loops within interconnected systems spanning neural, cognitive, and behavioral domains.

The integration of these simultaneously developing but largely separate applications of network science—in clinical neuroscience and psychopathology—creates exciting opportunities for a unified framework [3]. By introducing conventions from both fields and highlighting similarities, researchers can create a common language that enables the exploitation of synergies, ultimately leading to more comprehensive models of brain-behavior relationships in health and disease [2].

Comparative Analysis of Network Methodologies

Conceptual Models of Brain-Behavior Relationships

Table 1: Brain Modes Framework for Clinical Neuroscience

| Brain Mode Type | Clinical Definition | Research Example | Network Science Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unicity | A behavioural deficit is always linked to damage of a single brain structure | Theoretical only; may oversimplify neural systems | Single node failure point in network |

| Equivalence | Similar deficit appears after damage to any of several brain structures | Documented in aphasia, memory deficits, motor function | Several nodes are positive contributors with functional overlap |

| Association | Deficit appears only when two brain structures are simultaneously damaged | Theoretical in Balint syndrome, confabulations | Several nodes are positive contributors with joint functional contribution |

| Summation | Severe deficit appears when several structures are damaged simultaneously | Documented in language networks | Multiple positive contributors with redundant and synergistic interactions |

| Mutual Inhibition | Second lesion produces paradoxical behavioural improvement | Documented in visuospatial attention | Negative contributors with synergistic inhibitory interactions |

The brain modes framework provides a valuable taxonomy for classifying and understanding different types of brain-behavior relationships observed in clinical practice and research [4]. The equivalence mode, frequently observed clinically, epitomizes a situation in which damage to two separate structures provokes similar behavioural deficits, as seen in aphasia, memory loss, and executive deficits where different lesion locations produce comparable symptoms [4]. For instance, verbal paraphasias have been linked to either temporal or caudate lesions, while non-fluent aphasia depends on frontal or putamen lesions [4].

The association mode describes scenarios where two brain regions must both be damaged to generate a neurological deficit, observed theoretically in conditions such as Balint syndrome, reduplicative paramnesia, confabulations, global aphasia, and dysexecutive functions [4]. In contrast, the summation mode characterizes interactions where lesions in multiple regions result in specific deficits that prove greater than the sum of individual lesion effects when structures are simultaneously damaged [4].

Most intriguingly, the more recently described mutual inhibition/masking summation mode accounts for situations where a second lesion produces paradoxical behavioural improvement from a deficit generated by an earlier lesion, a phenomenon documented clinically and theoretically [4]. This fifth mode illustrates the counterintuitive dynamics that can emerge in complex neural networks and highlights the importance of inhibitory interactions in brain function.

Analytical Tools and Computational Approaches

Table 2: Network Science Tools for Clinical Neuroscience Research

| Tool/Platform | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NetworkX | Network analytics in Python | User-friendly, extensive documentation, Matplotlib integration | Slow with larger networks, computational limitations [1] |

| iGraph | Large network analysis | Superior computational speed, efficient for large datasets | Steeper learning curve, especially in Python [1] |

| Graph-tool | Efficient network analysis | C++ implementation, fast statistical tools | Less beginner-friendly [5] |

| Cytoscape | Biological network visualization | Intuitive interface, extensive app ecosystem | Poor performance with very large networks [5] |

| Gephi | Network visualization | Free, point-and-click interface, publication-quality visuals | Desktop application only [1] |

| Brain Connectivity Toolbox (BCTPY) | Network neuroscience | Specialized for brain networks, comprehensive metrics | Domain-specific, less generalizable [5] |

| Network Repository | Data source & benchmarking | Thousands of real-world network datasets, interactive visualization | Varying data quality and documentation [6] |

The methodological ecosystem for network science in clinical research encompasses diverse tools optimized for different aspects of network analysis. For Python-based analyses, NetworkX serves as an accessible entry point with its user-friendly syntax that "almost feels like speaking in English," though its computational speed proves limiting with larger networks [1]. For enhanced performance with substantial datasets, iGraph (C implementation) and graph-tool (C++ implementation) offer superior computational efficiency at the cost of a steeper learning curve [1] [5].

Specialized platforms like Cytoscape cater specifically to biological networks with intuitive graphical interfaces that don't require programming knowledge, supported by an extensive ecosystem of apps (such as ClueGo and MCODE) for functional enrichment and molecular profiling analyses [5]. Meanwhile, Gephi remains a popular choice for network visualization, capable of producing publication-quality figures through its point-and-click interface [1].

For researchers seeking standardized datasets, Network Repository provides the first interactive scientific network data repository with thousands of real-world network datasets across 30+ domains, facilitating benchmarking and methodological comparisons [6]. The integration of these tools creates a robust methodological foundation for applying network approaches to clinical neuroscience questions.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Multi-Modal Data Integration Methodology

The integration of brain and behavioral data represents a core challenge in clinical network neuroscience. Blanken and colleagues (2021) have proposed three methodological avenues for combining networks of brain and behavioral data [2] [3]:

Network Regression Frameworks: These approaches examine how brain networks predict behavioral variables or networks, using techniques such as network-based statistics or multivariate regression models that incorporate network features as predictors.

Data Fusion Methods: Including joint embedding techniques, these methods simultaneously represent brain and behavioral data in a shared latent space, allowing researchers to identify dimensions that capture covariation between brain and behavioral features.

Multi-Layer Network Models: These frameworks represent brain and behavioral data as different layers in a multi-layer network, enabling the quantification of cross-layer interactions and the identification of motifs that span neural and behavioral domains.

These approaches enable researchers to move beyond correlational analyses toward models that can capture the dynamic, multi-level interactions between neural systems and behavioral manifestations.

Validation Protocols for Brain-Behavior Associations

Validating network models of brain-behavior relationships requires rigorous methodological standards:

Lesion Network Mapping Protocol:

- Lesion Identification: Precisely delineate lesion boundaries using structural neuroimaging (e.g., MRI, CT)

- Network Localization: Map lesions onto reference brain networks using normative connectome data (e.g., from the Human Connectome Project)

- Symptom Assessment: Quantify behavioral deficits using standardized clinical instruments

- Network Inference: Identify networks commonly associated with specific symptoms across patients

- Predictive Validation: Test whether network locations predict symptoms in independent cohorts

Multiperturbation Shapley Value Analysis (MSA) Protocol: The MSA approach builds on game-theoretic principles to characterize functional contributions of brain structures by analyzing isolated and combined regional contributions to clinical deficits [4]. This method:

- Treats brain structures as "players" in a complex coalition (network or system)

- Quantifies both positive and negative contributions of each structure

- Reveals redundant interactions (functional overlap) and synergistic interactions (complementary functions)

- Has been successfully applied to post-stroke lesion data to establish causal implications of grey and white matter structures in specific cognitive domains [4]

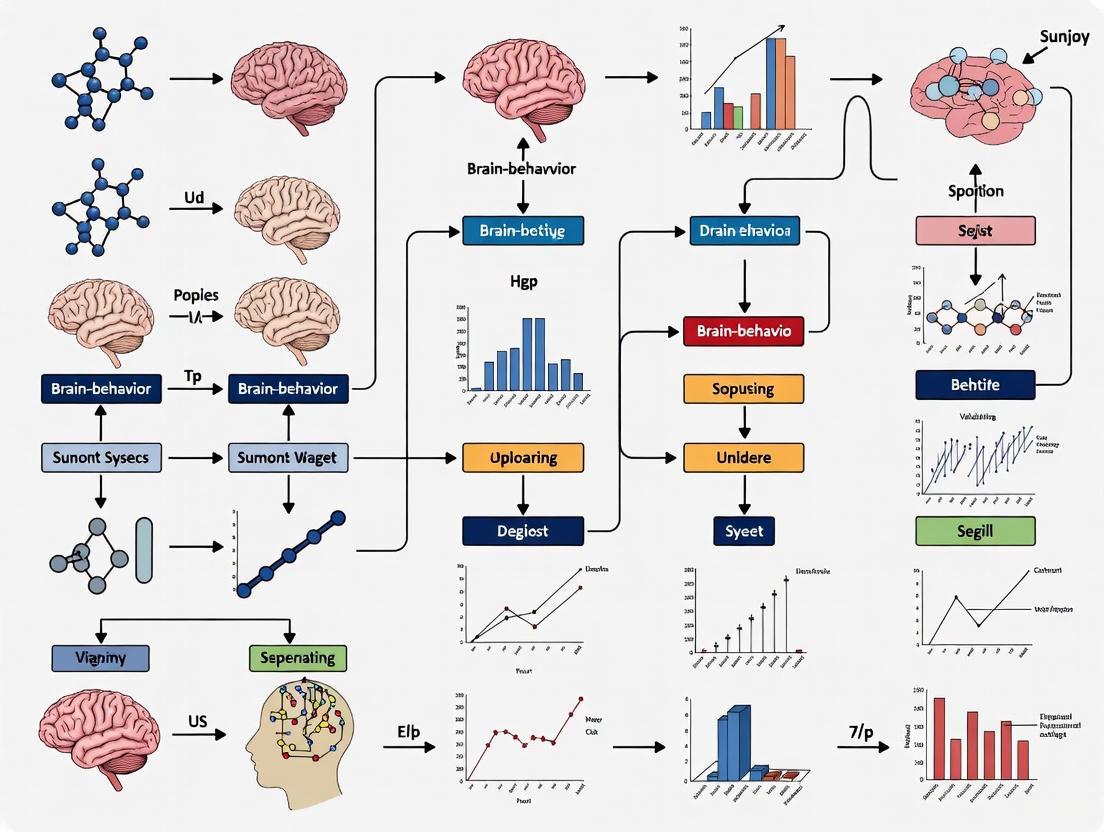

Network Analysis Workflow for Clinical Neuroscience

Application to Clinical Research: Autism Case Example

Autism research accurately represents research lines in both network neuroscience and psychological networks, providing an illustrative case example of how network approaches can bridge brain and behavior [2] [3]. In autism studies, network approaches have been applied to:

Brain Network Organization: Revealing altered connectivity patterns, particularly in social brain networks, using resting-state functional MRI and diffusion tensor imaging.

Symptom Networks: Mapping relationships between core autistic features (social communication challenges, restricted interests, repetitive behaviors) and co-occurring conditions (anxiety, sensory sensitivities).

Multi-Level Integration: Examining how alterations in neural network organization relate to symptom network structure, potentially identifying key pathways that bridge biological and behavioral manifestations of autism.

This integrative approach demonstrates how network science can move beyond descriptive comorbidity patterns toward mechanistic models that explain how alterations in neural system organization give rise to characteristic behavioral profiles.

Computational Tools for Network Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Network Neuroscience

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Libraries | NetworkX, iGraph, BCTPY | Network construction, analysis, and statistics | Python/R packages |

| Visualization Platforms | Gephi, Cytoscape, Circos | Network visualization and exploration | Desktop applications |

| Data Resources | Network Repository, Stanford SNAP | Benchmarking datasets, reference networks | Online repositories |

| Specialized Analysis | graph-tool, MSA algorithms | Advanced network statistics, causal inference | Python/C++ libraries |

| Educational Resources | "Network Science" (Barabási), "A First Course in Network Science" | Theoretical foundations, practical tutorials | Textbooks, online materials |

The "Research Reagent Solutions" for network neuroscience encompass both software tools and educational resources that enable researchers to implement network approaches effectively. For programming-based analyses, NetworkX provides the most accessible entry point with comprehensive documentation and extensive algorithmic coverage [1] [5]. More computationally intensive analyses may leverage iGraph or graph-tool for improved performance with large networks [1].

Visualization represents a critical component of network analysis, with Gephi offering publication-quality outputs through an intuitive point-and-click interface [1]. For biological networks specifically, Cytoscape and its associated apps (ClueGo, MCODE) provide specialized functionality for molecular interaction networks and pathway analyses [5].

Foundational educational resources include Barabási's comprehensive textbook "Network Science" (2016), which offers an all-inclusive technical foundation in network mathematics, and "A First Course in Network Science" with its practical programming tutorials using real datasets like the C. Elegans neural network [1] [5].

Research Resource Integration Pipeline

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

The integration of network science approaches in clinical neuroscience and psychopathology holds significant promise for advancing both basic understanding and clinical applications. Future developments will likely focus on:

Dynamic Network Models: Moving beyond static network representations to capture temporal dynamics in brain-behavior relationships, potentially using time-varying network approaches from graph theory.

Personalized Network Medicine: Applying network principles to develop individualized models of brain-behavior relationships that can inform personalized neurorehabilitation therapies [4].

Multi-Scale Integration: Developing frameworks that bridge molecular, cellular, systems, and behavioral levels of analysis to create comprehensive network models of clinical conditions.

Intervention Targeting: Using network identification of key nodes and edges to inform targeted interventions, whether through neuromodulation, pharmacological approaches, or behavioral therapies.

As these methodologies continue to mature, network science approaches are poised to transform how researchers and clinicians conceptualize, diagnose, and treat conditions spanning the spectrum from neurological disorders to psychiatric conditions. By providing quantitative frameworks for understanding complex brain-behavior relationships, network science enables a more nuanced, systems-level approach to clinical neuroscience that acknowledges the inherent complexity of both brain organization and behavioral manifestation.

In clinical neuroscience, the brain is a complex network of interconnected regions. Graph theory provides a powerful mathematical framework to model this organization, transforming neuroimaging data into graphs where nodes represent brain areas and edges represent the structural or functional connections between them [7]. Analyzing the network topology—the arrangement of these nodes and edges—allows researchers to quantify brain organization and validate robust brain-behavior associations [8]. This guide compares the core concepts and analytical approaches used to unravel the brain's connectome.

Foundational Concepts of Network Topology

The properties below are fundamental for analyzing and comparing brain networks. They help translate the complex structure of the brain into quantifiable metrics.

Table 1: Key Topological Properties of Brain Networks

| Topological Concept | Definition & Analogy | Relevance in Clinical Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|

| Node Degree [7] | The number of connections a node has. Analogous to the number of direct flights from an airport hub. | Nodes with a high degree (hubs) are critical for integration of brain information; their disruption is implicated in disorders like schizophrenia [7]. |

| Shortest Path [7] | The minimum number of edges required to travel between two nodes. Analogous to the most efficient route between two locations. | Shorter paths enable efficient information transfer. Longer paths may indicate disrupted neural communication in psychiatric illness [7]. |

| Scale-Free Property [7] | A network structure where most nodes have few connections, but a few hubs have many. | Brain networks are thought to be scale-free, making them robust to random damage but vulnerable to targeted hub attacks, as seen in some neurodegenerative diseases [7]. |

| Transitivity (Clustering) [7] | The probability that two nodes connected to a common node are also connected to each other. Analogous to "the friend of my friend is also my friend." | High clustering indicates specialized, modular processing within local brain communities. Alterations are seen in autism spectrum disorder [7]. |

| Centrality [7] | A family of measures quantifying a node's importance for network connectivity (e.g., betweenness centrality tracks how many shortest paths pass through a node). | Identifies bottleneck regions critical for global information flow. Centrality changes are documented in PTSD and depression [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Network Neuroscience

Translating raw neuroimaging data into a graph for analysis requires a structured workflow. The methodology below outlines the standard pipeline for constructing and analyzing brain networks.

Objective: To reconstruct a structural or functional brain network from neuroimaging data and calculate its topological properties to identify correlates of behavior or clinical symptoms.

Workflow Summary: The process involves defining the network nodes and edges from imaging data, constructing a connectivity matrix, and then applying graph theory to compute topological metrics.

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution neuroimaging data. For structural networks, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) is used to trace white matter tracts [8]. For functional networks, functional MRI (fMRI) captures blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals to infer correlated neural activity between regions [8].

- Network Construction:

- Node Definition: The brain is parcellated into distinct regions of interest (ROIs) using a standardized atlas. Each ROI becomes a node in the graph.

- Edge Definition: For structural networks, the number of white matter streamlines between ROIs, derived from dMRI, defines edge weight. For functional networks, the statistical correlation (e.g., Pearson's correlation) between the fMRI time series of two ROIs defines the edge weight.

- Connectivity Matrix: The result is an N x N symmetric matrix (where N is the number of nodes), where each cell represents the connection strength between two nodes.

- Graph Analysis: The connectivity matrix is treated as a graph, and its topology is interrogated using the metrics defined in Table 1. Software toolboxes like the Brain Connectivity Toolbox are typically used to calculate degree, shortest path length, clustering coefficient, and centrality for each node and for the network as a whole.

- Statistical Comparison & Clinical Validation: The computed graph metrics are compared between a patient group (e.g., individuals with PTSD) and a healthy control group [8]. Statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANCOVA) identify significant differences in topology. These differences are then correlated with clinical measures (e.g., symptom severity, cognitive test scores) to establish brain-behavior associations [8].

Comparative Analysis of Network Mapping Techniques

Different techniques for mapping brain circuits offer trade-offs between spatial resolution and invasiveness. The table below compares methods used to derive and validate network-based treatment targets.

Table 2: Comparison of Network Mapping & Modulation Techniques

| Methodology | Spatial Resolution | Invasiveness | Key Application in Network Validation | Representative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Network Mapping [8] | High (MRI-based) | N/A (Post-hoc analysis) | Maps the network of brain lesions that cause a specific symptom to identify therapeutic targets. | A specific brain network connected to lesion locations that modify psychiatric symptoms can be identified [8]. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) [8] | Moderate (~3mm) | Non-invasive | Measures functional connectivity to identify dysregulated circuits in patient populations. | Can identify multimodal neural signatures of PTSD susceptibility post-trauma [8]. |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) [8] | Moderate (~1cm) | Non-invasive | Tests causality by modulating a node and measuring behavioral and network-wide effects. | Used in clinical trials to test brain stimulation targets derived via network mapping [8]. |

| Transcranial Ultrasound (TUS) [8] | High (~2-3mm) | Non-invasive | Allows focal neuromodulation of deep-brain areas (e.g., amygdala) implicated in psychiatric disease [8]. | A developing technique for rebalancing neural circuit stability in deep-brain areas [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and tools for conducting graph-based analyses in clinical neuroscience.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Network Neuroscience Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Diffusion MRI Tractography | Reconstructs the white matter structural pathways (the "wires") of the brain, providing the data to define structural edges in a brain graph [8]. |

| Resting-State fMRI | Measures spontaneous, low-frequency brain activity to map functional connectivity, defining the edges for a functional brain network without requiring a task [8]. |

| Standardized Brain Atlas | A predefined map of the brain's regions used to consistently parcellate the brain into nodes across all study participants, ensuring comparability [7]. |

| Brain Connectivity Toolbox | A collection of standardized functions and algorithms for calculating graph theory metrics (e.g., centrality, clustering) from network data [7]. |

| Network Mapping Software | Specialized software for visualizing and analyzing complex networks, offering layout algorithms and interactive exploration to identify patterns like hubs and clusters [9]. |

Advanced Analysis: From Static to Dynamic Networks

The brain is a dynamic system, and its network topology changes over time. Advanced analyses move beyond static snapshots to capture this temporal nature, which is crucial for understanding processes like learning or the fluctuating symptoms in mood disorders.

Summary of Dynamic Analysis: This approach involves acquiring a series of brain network snapshots over time (e.g., using multiple fMRI scans) [10]. Analyzing this time series reveals how network properties evolve, allowing researchers to:

- Identify temporal hubs that flexibly switch their connections.

- Track network state trajectories to see how the brain transitions between different organizational patterns.

- Calculate time-varying centrality to understand how the functional importance of a brain region fluctuates, potentially linking these dynamics to behavioral states or symptom changes [10].

Analytical Framework Comparison at a Glance

The following table provides a high-level comparison of three analytical frameworks used for validating brain-behavior associations in clinical neuroscience, summarizing their core approaches, data integration capabilities, and primary applications.

| Framework Name | Core Analytical Approach | Type of Data Integrated | Key Output | Stated Advantage | Primary Application in Reviewed Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretable & Integrative Deep Learning [11] | Multi-view unsupervised deep learning | Imaging (structural MRI), clinical behavioral scores, genetics | Stable brain-behavior associations | Identifies relevant associations with incomplete data; isolates variability from confounders | Discovering brain-behaviour links in psychiatric syndromes |

| RSRD "Barcode" with hctsa [12] | Highly comparative time-series analysis (hctsa) | Resting-state fMRI (BOLD time-series) | 44 reliable RSRD features; individualized brain "barcode" | High test-retest reliability; generalizable across cohorts and life stages | Linking intra-regional dynamics to substance use and cognitive abilities |

| i-ECO (Integrated-Explainability through Color Coding) [13] | Dimensionality reduction & color-coding of fMRI metrics | fMRI (ReHo, ECM, fALFF) | Integrated color-coded brain maps; high discriminative power | High diagnostic classification power; accessible visualization for clinical practice | Discriminating between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, ADHD, and controls |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

This section provides the detailed methodologies and quantitative results from the key studies that form the basis of this comparative guide.

Interpretable & Integrative Deep Learning Protocol

- Objective: To move beyond single-data-source classification and discover stable brain-behavior associations across psychiatric syndromes by integrating multiple data sources [11].

- Dataset: Healthy Brain Network cohort [11].

- Input Features: Clinical behavioral scores and brain imaging features from structural MRI [11].

- Methodology Workflow:

- Key Quantitative Findings:

Resting-State Regional Dynamics (RSRD) "Barcode" Protocol

- Objective: To comprehensively characterize intra-regional brain dynamics and extract a reliable, generalizable set of features that serve as an individual-specific 'barcode' for linking to behavior [12].

- Datasets:

- Input Features: ~5,000 time-series features per brain region from resting-state fMRI (BOLD) data, extracted using highly comparative time-series analysis (hctsa) [12].

- Methodology Workflow:

- Key Quantitative Findings:

| Analysis Type | Specific Metric/Association | Result / Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Reliability | Intra-class Correlation (ICC) of 44 refined features (HCP-YA) | Mean ICC = 0.587 ± 0.06 [12] |

| Individual Identification | Fingerprinting Accuracy | Up to 95% across sessions [12] |

| Cross-Cohort Reliability | ICC correlation (HCP-YA vs. HCP-D vs. MSC) | Spearman r = 0.96 - 0.99 [12] |

| Brain-Behavior Associations | Nonlinear autocorrelations in unimodal regions | Linked to substance use traits [12] |

| Brain-Behavior Associations | Random walk dynamics in higher-order networks | Linked to general cognitive abilities [12] |

i-ECO Integrated Visualization Protocol

- Objective: To provide an integrative and easy-to-understand method for analyzing and visualizing fMRI results by combining multiple analysis dimensions, with high power for discriminating psychiatric diagnoses [13].

- Dataset: UCLA Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics (130 healthy controls, 50 schizophrenia, 49 bipolar disorder, 43 ADHD) [13].

- Input Features: Three fMRI metrics averaged per Region of Interest (ROI) [13]:

- Methodology Workflow:

- Key Quantitative Findings:

- The i-ECO methodology showed between-group differences that could be easily appreciated visually [13].

- A convolutional neural network model trained on these integrated color-coded images achieved a precision-recall Area Under the Curve (PR-AUC) of >84.5% for each diagnostic group on the test set [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key resources and computational tools essential for implementing the analytical frameworks discussed in this guide.

| Item Name | Type / Category | Key Function in the Research Context | Example from Featured Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Source Neuroimaging Cohorts | Data Resource | Provide large-scale, often open-access, datasets with imaging and behavioral data for discovery and validation. | Healthy Brain Network [11]; HCP-YA, HCP-D [12]; UCLA CNP [13] |

| hctsa Toolbox | Computational Tool | Automates the extraction of a massive, comprehensive set of time-series features from data, enabling data-driven discovery. | Used to extract ~5,000 features per region for RSRD profiling [12] |

| Stability Selection | Statistical Method | Improves the robustness of feature selection in high-dimensional data, reducing false discoveries. | Combined with digital avatars to find stable brain-behaviour associations [11] |

| AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages) | Software Suite | A comprehensive tool for preprocessing and analyzing functional and structural MRI data. | Used for fMRI preprocessing in the i-ECO method [13] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Machine Learning Model | A deep learning architecture particularly effective for image classification and pattern recognition tasks. | Used to classify diagnostic groups based on i-ECO color-coded images [13] |

| Test-Retest Reliability Analysis | Statistical Protocol | Quantifies the consistency of a measurement across multiple sessions, critical for individualized biomarkers. | Used to select the 44 most reliable RSRD features (ICC > 0.5) [12] |

Identifying Core Brain-Behavior Networks in Health and Disease

In clinical neuroscience, a paradigm shift is occurring from studying isolated brain regions to investigating complex, large-scale networks. The brain is fundamentally a complex system of interconnected networks, and understanding behavior—in both health and disease—requires mapping these core brain-behavior networks. This approach conceptualizes the brain as a series of interacting networks where cognitive functions and clinical symptoms emerge from the dynamic interplay between distinct but interconnected systems [14]. Research now focuses on identifying how these networks reconfigure across different cognitive loads and how their disruption manifests in various neuropsychiatric disorders [15]. The promise of this network approach lies in creating a unified framework to tackle one of the most fundamental questions in neuroscience: understanding the precise links between brain connectivity and behavior [2].

Core networks consistently identified across studies include the salience network (SN) for detecting behaviorally relevant stimuli, the central executive network (CEN) for cognitive control and working memory, and the default mode network (DMN) for self-referential thought [16] [14]. These networks form the fundamental architecture upon which brain-behavior relationships are built, and their interactions create the neural basis for complex human behavior. This guide provides a comparative analysis of methods for identifying these networks, their alterations in disease states, and the experimental approaches driving discoveries in cognitive network neuroscience.

Core Brain Networks: Architecture and Function

Defining the Major Networks

The foundation of brain-behavior relationships lies in several intrinsically connected large-scale networks. Each network supports distinct but complementary aspects of cognitive and emotional functioning:

Salience Network (SN): Comprising the dorsal anterior cingulate and anterior insula regions, this network functions as an attentional gatekeeper, identifying and filtering internal and external stimuli to guide behavior by detecting survival-relevant events in the environment [16] [17]. It acts as a critical interface between cognitive, emotional, and homeostatic systems, essentially determining which stimuli warrant attention and action [17].

Central Executive Network (CEN): Consisting of regions in the middle and inferior prefrontal and parietal cortices, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), this network is engaged by higher-level cognitive tasks and is crucial for adaptive cognitive control, working memory, and goal-directed behavior [16] [14].

Default Mode Network (DMN): Including regions in the medial frontal cortex and posterior cingulate, this network typically reduces its activity during active cognitive demands and is associated with attention to internal emotional states and self-referential processing [16]. During cognitively demanding tasks, proper DMN suppression is essential for maintaining focus on external stimuli.

Frontoparietal Network (FPN): Often overlapping with conceptions of the CEN, this network demonstrates high flexibility across tasks and is crucial for cognitive control and task switching [15]. Research has shown it to be one of the most flexible networks, changing its connectivity patterns significantly across different cognitive states.

Network Interactions in Cognitive Processing

The dynamic interactions between these core networks create the neural basis for complex behavior. Rather than operating in isolation, these networks engage in a carefully choreographed reciprocal relationship [16]. The salience network is thought to play a crucial role in switching between the default mode and executive networks, facilitating transitions between internal and external focus [16].

During working memory tasks, studies have demonstrated that the FPN and DMN exhibit distinct reconfiguration patterns across cognitive loads. Both networks show strengthened internal connections at low demand states compared to resting state, but as cognitive demands increase from low (0-back) to high (2-back), some connections to the FPN weaken and are rewired to the DMN, whose connections remain strong [15]. This dynamic reconfiguration illustrates how network interactions adapt to support changing behavioral demands.

Table 1: Core Brain Networks and Their Behavioral Correlates

| Network | Key Regions | Primary Functions | Behavioral Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salience Network (SN) | Dorsal anterior cingulate, anterior insula | Detecting relevant stimuli, attentional control | Interoceptive awareness, emotional response, attention switching |

| Central Executive Network (CEN) | DLPFC, inferior parietal cortex | Cognitive control, working memory, decision-making | Problem-solving, planning, working memory performance |

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate | Self-referential thought, memory consolidation, social cognition | Mind-wandering, autobiographical memory, theory of mind |

| Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Lateral prefrontal, posterior parietal | Task switching, cognitive control, adaptive processing | Cognitive flexibility, task engagement, attention control |

Methodological Comparison: Mapping Brain-Behavior Networks

Analytical Approaches for Network Identification

Multiple analytical frameworks have been developed to identify and quantify brain-behavior networks, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate application scenarios:

Graph Theory: This approach models the brain as a graph composed of nodes (brain regions) and edges (region-region connections), allowing quantification of topological organization through metrics like clustering coefficient, path length, and modularity [18] [14]. Graph theory excels at characterizing the overall architecture of brain networks but faces challenges in directly linking specific network features to particular behaviors [18].

Network-Based Statistic (NBS): Specifically designed for identifying connections that differ between groups (e.g., healthy controls vs. clinical populations), NBS controls the family-wise error rate when mass-univariate testing is performed at every connection [19]. Unlike graph theory, NBS exploits the extent to which connections comprising a contrast of interest are interconnected, offering increased power for identifying dysconnected subnetworks [19].

Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM): A data-driven approach that searches for all neural connections related to human behaviors without prior bias [18]. CPM builds models that predict individual differences in behavior from connectivity patterns, often revealing novel connections not previously associated with the examined behavior, though these findings require careful interpretation and validation [18].

Granger Causality: Goes beyond correlation to examine potential causal influences between brain regions by testing whether activity in one region predicts future activity in another [16]. This method has been particularly valuable for examining directional relationships between networks, such as impaired excitatory causal outflow from the anterior insula to the DLPFC in schizophrenia [16].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Identifying Brain-Behavior Networks

| Method | Application Scenarios | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Theory | Quantifying topological architecture of brain networks | Provides multiple metrics to describe network organization | Ambiguous behavioral interpretation; no causal inference |

| Network-Based Statistic (NBS) | Identifying group differences in connectivity | Enhanced power to detect interconnected dysconnected subnetworks | Limited to group comparisons rather than individual prediction |

| Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM) | Predicting behavior from whole-brain connectivity | Data-driven, unbiased approach discovering novel connections | Findings may be difficult to interpret; requires validation |

| Granger Causality | Examining directional influences between regions | Provides evidence for potential causal relationships | Controversial regarding true causal identification; sensitive to confounds |

| Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) | Classifying cognitive states from brain activity | High sensitivity for recognizing behavior-related states | Complex interpretation of neural mechanisms |

Experimental Workflow for Network Identification

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for identifying core brain-behavior networks across health and disease, integrating multiple methodological approaches:

This workflow begins with data acquisition using neuroimaging techniques like fMRI, followed by extensive preprocessing to address artifacts (particularly motion correction, crucial for clinical populations) [16] [18]. The analysis phase then applies complementary methodological approaches to identify core networks and their relationship to behavioral measures, with final validation through replication and clinical application.

Network Alterations in Disease States

Schizophrenia: A Dysconnection Syndrome

Schizophrenia represents a classic example of network dysfunction, often described as a "dysconnection" syndrome characterized by impaired causal interactions between the salience and central executive networks [16]. Research using Granger causality has demonstrated specific deficits in the excitatory causal outflow from the anterior insula (SN node) to the DLPFC (CEN node), along with impaired inhibitory feedback from the DLPFC to salience network regions [16].

Network-Based Statistic analysis has identified an expansive dysconnected subnetwork in schizophrenia, primarily comprising fronto-temporal and occipito-temporal dysconnections [19]. These network alterations correlate with clinical symptoms, as the severity of deficits in interactions between salience and CEN systems predicts impairment in symptom severity and processing speed [16]. Additionally, research on self-awareness networks in schizophrenia has revealed that approximately 40% of self-awareness connectivity is altered, affecting the integration of internal states with external reality [20].

Persisting Post-Concussion Symptoms: Salience Network Dysfunction

In persisting symptoms after concussion (PSaC), research has identified the salience network as a core disrupted network underlying diverse symptoms [17]. Unlike the broader network dysfunction in schizophrenia, PSaC involves specific perturbations to the salience network's ability to filter and prioritize internal and external stimuli, leading to combinations of headache, depression, vestibular dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and fatigue [17].

This salience network dysfunction has direct therapeutic implications, as researchers have used network identification to propose novel neuromodulation targets within the DLPFC that are distinct from traditional depression targets [17]. This represents a prime example of how identifying core disrupted networks can guide targeted interventions.

Comparative Network Alterations Across Conditions

The table below compares network alterations across different clinical conditions, highlighting both shared and distinct patterns of network dysfunction:

Table 3: Comparative Network Alterations in Clinical Conditions

| Condition | Core Network Alterations | Behavioral/Cognitive Manifestations | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Impaired SN-CEN interactions; widespread dysconnections | Reality distortion, cognitive deficits, impaired self-awareness | Potential network-based neuromodulation targets |

| Persisting Concussion Symptoms | Salience network perturbation | Headache, dizziness, cognitive impairment, fatigue | Distinct DLPFC targets for rTMS different from depression |

| Major Depressive Disorder | Altered self-awareness networks (20% of connections) | Negative self-referential thought, rumination | Overlap with schizophrenia alterations (90% of MDD changes overlap) |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Default mode network disruption | Memory deficits, disorientation | Network stability measures may aid early detection |

Conducting rigorous research on brain-behavior networks requires specialized tools and analytical resources. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications in this field:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Network Neuroscience

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Platforms | 3T fMRI scanners with high-resolution capabilities (e.g., Siemens Skyra) | Acquisition of BOLD signal for functional connectivity analysis [15] |

| Preprocessing Tools | FSL/FLIRT (motion correction), FSL/topup (distortion correction), ArtRepair | Addressing motion artifacts, distortion correction, and data quality control [16] [15] |

| Network Analysis Software | Brain Connectivity Toolbox, Network-Based Statistic toolbox | Graph theory metrics, statistical comparison of networks [19] [14] |

| Data Resources | Human Connectome Project, institutional datasets | Large-scale reference data for comparison and validation [17] [15] |

| Cognitive Task Paradigms | N-back working memory tasks, problem-solving tasks with performance feedback | Standardized behavioral measures linked to network activation [18] [15] |

| Statistical Platforms | MATLAB, Python, R with specialized neuroimaging packages | Implementation of custom analytical pipelines and statistical models |

Experimental Protocols for Network Identification

Protocol 1: Identifying Working Memory Networks Across Cognitive Loads

This protocol outlines the methodology for examining network reconfiguration across working memory demands, based on research with the Human Connectome Project dataset [15]:

Participant Population: Large cohorts (n=448+) including both healthy controls and clinical populations for comparison. Exclusion criteria typically include excessive head motion (>0.5mm), insufficient fMRI frames, and outlier behavioral performance [15].

Task Design: N-back working memory tasks with varying cognitive loads (0-back, 2-back) compared to resting state baseline. Tasks should include math problems or similar stimuli with performance feedback and sufficient trials per condition [18] [15].

fMRI Acquisition Parameters: Standardized protocols including: repetition time (TR)=720ms, echo time (TE)=33.1ms, flip angle=52°, voxel size=2.0mm isotropic, with both left-right and right-left phase encoding [15].

Preprocessing Pipeline: Critical steps include: (1) gradient nonlinearity distortion correction; (2) 6 DOF motion correction; (3) distortion correction and scalp stripping; (4) registration to standard space; (5) frame scrubbing and interpolation for excessive motion; (6) band-pass filtering (0.009-0.08Hz); (7) regression of mean signal, white matter/CSF components, and movement parameters [15].

Network Construction: Define nodes using established brain parcellations (e.g., Power-264 atlas), with edges representing functional connectivity between node time series [15].

Analysis Approach: Apply graph theory metrics (modularity, connectivity strength) and calculate reconfiguration intensity between task states using metrics like nodal connectivity diversity [15].

Protocol 2: Identifying Disorder-Specific Network Alterations

This protocol describes methods for identifying network alterations in clinical populations such as schizophrenia or persisting concussion symptoms:

Participant Selection: Carefully matched case-control design, with comprehensive clinical characterization including symptom severity measures and cognitive performance scores [16] [17].

Data Acquisition: Resting-state fMRI complemented by task-based fMRI targeting relevant cognitive domains (e.g., working memory for schizophrenia, attention tasks for concussion) [16] [17].

Analytical Methods: Primary analysis using Network-Based Statistic for group comparisons, complemented by Granger causality analysis for directional influences between networks [16] [19].

Symptom Correlation: Relate network metrics (connection strength, causal influences) to dimensional measures of symptom severity and cognitive performance [16].

Validation Analyses: Test robustness to potential confounds (particularly motion), replicate findings in independent samples, and compare to healthy control networks [16].

The identification of core brain-behavior networks represents a transformative approach in clinical neuroscience, moving beyond localized brain function to understand how distributed network interactions support cognitive processes and how their disruption produces clinical symptoms. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that each methodological approach—from graph theory to predictive modeling—offers complementary insights into these network dynamics.

The consistent identification of the salience, executive, and default mode networks as core systems across health and disease highlights their fundamental role in brain function. Their dynamic reconfiguration across cognitive demands and characteristic alterations in conditions like schizophrenia and persisting concussion symptoms provide critical insights for developing network-based biomarkers and targeted interventions. As methods continue to evolve, particularly with advances in machine learning and multi-modal integration, the field moves closer to a comprehensive understanding of how brain networks give rise to behavior in both health and disease.

The Role of Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets in Discovery

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets have revolutionized clinical neuroscience research by providing the extensive data required to detect subtle brain-behavior associations with unprecedented statistical rigor. These datasets address the critical challenge of small effect sizes in neuroscience, where individual laboratories rarely possess the resources to collect samples large enough for robust, reproducible findings [21] [22]. Initiatives like the Human Connectome Project (HCP), Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, and UK Biobank now offer researchers worldwide access to comprehensive neuroimaging, genetic, behavioral, and phenotypic data, accelerating discoveries in brain function and dysfunction [21]. This guide objectively compares these pivotal resources, detailing their experimental protocols, data structures, and applications in validating brain-behavior relationships for clinical and pharmaceutical development.

Major Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major international neuroimaging datasets, highlighting their unique research applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets

| Dataset Name | Primary Focus | Sample Size | Key Imaging Modalities | Associated Data | Access Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank [21] [22] | Population-scale biomedical database | ~500,000 participants (age 40-69) | Structural MRI, fMRI, DTI | Genetic, health records, cognitive measures | Application required |

| ABCD Study [21] [22] | Child and adolescent brain development | ~11,000+ children (age 9-10 at baseline) | Structural MRI, resting-state fMRI, task fMRI | Substance use, mental health, cognitive assessments | Controlled access |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) [21] [22] | Mapping human brain circuitry | ~1,200 healthy adults | High-resolution structural and functional MRI | Behavioral, demographic, genetic | Open access |

| China Brain Project [23] | Brain cognition, disease mechanisms, and brain-inspired intelligence | Targeted large-scale cohorts | Multi-scale neural mapping | Genetic, behavioral, clinical data | Varies by subproject |

| OpenNeuro [24] | Repository for shared neuroimaging data | Multiple datasets of varying sizes | Diverse MRI, EEG, MEG | Varies by contributed dataset | Open access |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets employ standardized protocols to ensure data quality and comparability across participants and sites. The ABCD study, for instance, utilizes harmonized structural MRI (T1-weighted and T2-weighted), resting-state fMRI, and diffusion tensor imaging across multiple research sites [21]. A critical preprocessing consideration is the choice between raw data (requiring 1.35 GB per individual in ABCD, totaling ~13.5 TB for initial release) versus processed data (connectivity matrices requiring only ~25.6 MB) [21] [22]. Preprocessing pipelines typically include motion correction, spatial normalization, and artifact removal, with organization increasingly following the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard to facilitate reproducibility [21] [22].

Analytical Approaches for Brain-Behavior Associations

Research utilizing these datasets employs several methodological frameworks to establish robust brain-behavior relationships:

Precision Functional Mapping (PFM): This approach, exemplified in recent psychedelic research, involves dense repeated sampling of individual participants to improve signal-to-noise ratio and effect size detection [25]. In a psilocybin study, PFM revealed persistent decreases in hippocampus-default mode network connectivity up to three weeks post-administration, suggesting a neuroanatomical correlate of long-term effects [25].

Effect Network Construction: Methods like the artificial immune system approach for fMRI data analyze effective connectivity networks by preprocessing steps including head motion correction, normalization, and resampling, followed by Bayesian network structure learning to identify directional influences between brain regions [26].

Multi-Modal Data Integration: Advanced analytical frameworks incorporate non-brain data through methods like multi-modal representation learning, which transforms diverse data types (imaging, genetic, behavioral) into unified vector representations that capture shared semantics and unique features [27].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for analyzing large-scale neuroimaging datasets:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key resources for working with large-scale neuroimaging datasets:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Storage Solutions | Local servers, Cloud storage (AWS, Google Cloud) | Store and manage large datasets (raw NIfTI: ~1.35GB/participant) | Essential for handling raw data; backup strategies critical [21] |

| Computational Frameworks | Bayesian network structure learning, Artificial immune systems | Identify directional influences in brain effect connection networks | Effective connectivity analysis from fMRI data [26] |

| Data Organization Standards | Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) | Standardize file naming and organization across datasets | Facilitates reproducibility and data sharing [21] [24] |

| Quality Control Tools | Framewise Integrated Real-time MRI Monitoring (FIRMM) | Monitor data quality during acquisition | Particularly valuable for challenging populations (e.g., psychedelic studies) [25] |

| Multi-Modal Integration | Multi-modal representation learning, Knowledge graph frameworks | Transform diverse data types into unified semantic representations | Enables integration of imaging with genetic, behavioral data [27] |

Experimental Evidence and Validation Approaches

Pharmacological Intervention Studies

Recent precision imaging drug trials demonstrate how large-scale datasets can elucidate neuropharmacological mechanisms. A randomized cross-over study investigating psilocybin (PSIL) versus methylphenidate (MTP) employed dense repeated sampling (resting-state and task-based fMRI) before, during, and after drug exposure in seven healthy volunteers [25]. This design revealed that PSIL produced context-dependent desynchronization of brain activity acutely, with individual differences strongly linked to subjective psychedelic experience [25]. The study implemented advanced methodologies including multi-echo EPI imaging, Nordic thermal denoising, and physiological signal monitoring to maximize data quality despite challenges like head motion and autonomic arousal [25].

Cross-Dataset Validation Strategies

Robust validation of brain-behavior associations often requires leveraging multiple datasets to bolster sample sizes, particularly for rare conditions or specific population subsets [21]. This approach demonstrates reproducibility across samples and analytical methods. For instance, findings related to cognitive aging might be validated across UK Biobank, ABCD, and targeted clinical cohorts to distinguish normative from pathological trajectories. The following diagram illustrates this multi-dataset validation framework:

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets represent transformative resources for clinical neuroscience, enabling robust detection of brain-behavior associations through unprecedented statistical power and methodological rigor. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that while these datasets share common strengths in addressing small effect sizes, they offer complementary strengths—from UK Biobank's population-scale breadth to ABCD's developmental trajectory mapping and precision imaging trials' mechanistic insights. Successful utilization requires careful consideration of dataset selection, analytical methodology, and validation frameworks. As these resources continue to grow and evolve, they promise to accelerate the translation of neurobiological insights into clinical applications for psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Multi-Modal Methods: Integrating Neuroimaging, AI, and Digital Biomarkers

Leveraging MRI and fMRI for Circuit-Level Functional Analysis

Validating brain-behavior associations is a central goal in clinical neuroscience, requiring precise tools to map the brain's functional circuits. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) are cornerstone technologies for this endeavor. While conventional MRI provides exquisite anatomical detail, fMRI captures dynamic, activity-related changes in the brain, offering a window into its functional organization [28]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these imaging modalities for circuit-level analysis, supporting the broader thesis that understanding brain network dynamics is crucial for identifying clinical biomarkers and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Technical Comparison: MRI vs. fMRI for Circuit-Level Analysis

The fundamental difference between these modalities lies in what they measure. Structural MRI visualizes neuroanatomy, whereas fMRI infers neural activity by detecting associated hemodynamic changes, most commonly using the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) contrast [28] [29]. The following section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of their capabilities and performance in functional circuit analysis.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MRI and fMRI for Circuit-Level Analysis

| Feature | Structural MRI | fMRI (BOLD Contrast) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Measured Signal | Tissue proton density (T1, T2 relaxation) | Changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin (dHb) concentration [29] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low (minutes) | Moderate (1-3 seconds typical TR) [29] |

| Spatial Resolution | Sub-millimeter | 1-3 millimeters (standard); limited by vascular source [28] [29] |

| Key Strength | Volumetry, cortical thickness, lesion detection | Mapping whole-brain functional networks & connectivity dynamics [30] |

| Circuit-Level Insight | Indirect (via structural connectivity) | Direct (via functional & effective connectivity) |

| BOLD Sensitivity | Not Applicable | ~1% signal change at 3T [29] |

| Primary Clinical Use | Diagnosis, surgical planning | Pre-surgical mapping, biomarker development [29] |

Table 2: Advanced Quantitative MRI (qMRI) Metrics for Microstructural Analysis [31]

| Quantitative Metric | Hypothesized Biological Sensitivity | Utility Across Age Span |

|---|---|---|

| T1ρ Adiabatic Relaxation | Cellular density [31] | Sharp changes in older age [31] |

| T2ρ Adiabatic Relaxation | Iron concentration [31] | Sharp changes in older age [31] |

| RAFF4 (Myelin Map) | Myelin density [31] | Sensitive in early adulthood, plateaus later [31] |

| Resting-State fMRI (wDeCe) | Global functional connectivity [31] | Sensitive in early adulthood, plateaus later [31] |

| NODDI (fICVF) | Neurite density [31] | Information missing |

| NODDI (ODI) | Neurite spatial configuration [31] | Information missing |

Experimental Protocols for Functional Connectivity Analysis

Task-Based fMRI and Functional Connectivity (TMFC)

Task-based fMRI analyses how the brain reconfigured its functional connectivity in response to specific cognitive demands. Several methods exist to derive Task-Modulated Functional Connectivity (TMFC) matrices, each with distinct strengths.

Table 3: Comparison of Task-Modulated Functional Connectivity (TMFC) Methods [30]

| Method | Description | Best For | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychophysiological Interaction (sPPI/gPPI) | Models interaction between a physiological brain signal and a psychological task variable. | Block designs; event-related designs (with deconvolution) [30] | With deconvolution, shows high sensitivity in block and rapid event-related designs [30] |

| Beta-Series Correlation (BSC-LSS) | Correlates trial-by-trial beta estimates (from LSS regression) across brain regions. | Event-related designs with variable ISIs [30] | Most robust method to HRF variability; best for non-rapid event-related designs [30] |

| Correlation Difference (CorrDiff) | Simple difference in correlation between two task conditions. | Block designs [30] | Susceptible to spurious co-activations, especially in event-related designs [30] |

| Background FC (BGFC) | Correlates residuals after regressing out task activations. | Intrinsic, task-independent connectivity [30] | Similar to resting-state FC; does not isolate task-modulated changes [30] |

A biophysically realistic simulation study comparing these methods concluded that:

- The most sensitive method for rapid event-related designs and block designs is sPPI and gPPI with a deconvolution procedure [30].

- For other event-related designs, the BSC-LSS method is superior [30].

- cPPI (Correlational PPI) is not capable of reliably estimating TMFC [30].

- TMFC methods can recover rapid (100 ms) modulations of neuronal synchronization even from slow fMRI data (TR=2s), with faster acquisitions (TR<1s) improving sensitivity [30].

Resting-State fMRI (rs-fMRI) Dynamics Analysis

In contrast to task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI studies spontaneous brain fluctuations to map intrinsic functional architecture. Several methods characterize these dynamics, yielding different insights.

Table 4: Comparison of Resting-State fMRI Dynamics Methods [32]

| Method | Description | Temporal Characterization | Sensitivity to Quasi-Periodic Patterns (QPPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sliding Window Correlation (SWC) | Computes correlation between regional time series within a sliding temporal window. | Tracks slow, continuous changes in functional connectivity [32] | Low sensitivity (with 60s window); cluster identity stable during 24s QPP sequences [32] |

| Phase Synchrony (PS) | Measures the instantaneous phase synchrony between oscillatory signals from different regions. | Captures rapid, transient synchronization events [32] | High sensitivity; mid-point of most QPP sequences grouped into a single cluster [32] |

| Co-Activation Patterns (CAP) | Identifies recurring, instantaneous spatial patterns of high co-activation. | Identifies brief, recurring brain-wide activity patterns [32] | High sensitivity; separates different phases of QPP sequences into distinct clusters [32] |

Visualizing Core Concepts and Workflows

The BOLD fMRI Signal Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the neurovascular coupling process that generates the BOLD fMRI signal, from neural activity to the measured MR signal change.

Figure 1: The BOLD fMRI Signal Pathway. This diagram outlines the cascade from neural activity to the measured BOLD signal, involving neurovascular coupling, hemodynamic changes, and their effect on MRI relaxation parameters [28] [29].

Functional Connectivity Analysis Workflow

This workflow outlines the standard pipeline for processing fMRI data to extract both task-based and resting-state functional connectivity metrics.

Figure 2: Functional Connectivity Analysis Pipeline. The standard workflow from raw data acquisition to statistical validation of network measures, highlighting parallel paths for task and resting-state analyses [30] [29] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Resources for fMRI Circuit-Level Analysis

| Resource / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AAL3 Brain Atlas | Standardized parcellation of the brain into Regions of Interest (ROIs) for connectivity analysis [33] | Mapping fMRI scans to a consistent anatomical model to investigate brain-wide connectivity patterns [33] |

| Biophysically Realistic Simulation Platforms | Simulates neuronal activity and BOLD signals using neural mass models (e.g., Wilson-Cowan) and hemodynamic models (e.g., Balloon-Windkessel) [30] | Validating and comparing TMFC methods with known ground-truth connectivity [30] |

| Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) | A machine learning approach to extract features revealing complex functional connectivity patterns from fMRI data [33] | Classifying Alzheimer's disease stages by analyzing connectivity patterns between ROIs [33] |

| General Linear Model (GLM) Software | Statistical framework for modeling task-related BOLD responses and removing confounds (e.g., motion, drift) [29] | Isulating task-evoked activity from noise in block or event-related designs [29] |

| High-Field MRI Scanners (3T & 7T) | Provide increased BOLD signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial specificity [28] [29] | Improving detection of subtle circuit-level dysfunction in clinical populations [33] |

| Public Neuroimaging Datasets | Large-scale, curated datasets for method development and validation (e.g., OASIS, ADNI, HCP) [33] [30] | Benchmarking new analytical approaches against standardized data from healthy and clinical cohorts [33] |

AI and Machine Learning for Pattern Recognition in Neural Data

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative technologies for analyzing complex neural data, enabling researchers to decode brain function and validate brain-behavior associations. In clinical neuroscience networks research, these technologies provide the computational power needed to identify meaningful patterns across massive datasets derived from neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and behavioral assessments. The integration of AI-driven pattern recognition is particularly valuable for linking multiscale brain network features to cognitive processes and pathological states, thereby accelerating therapeutic discovery for central nervous system (CNS) disorders [34] [35].

This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and methodological approaches of different AI technologies used for pattern recognition in neural data. We focus on providing clinical neuroscience researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and protocols to inform their selection of analytical tools for brain-behavior association studies.

Comparative Analysis of AI Technologies for Neural Data

Performance Benchmarks Across Neural Data Types

Table 1: Performance comparison of AI models on different neural data analysis tasks

| AI Model/Architecture | Primary Data Type | Task | Performance Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel High-Resolution Attention Decoding [36] | Prefrontal Local Field Potentials (LFP) | Decoding (x,y) locus of covert attention | Decoding Accuracy | High accuracy comparable to Multi-Unit Activity (MUA) | Non-human primate study; information maximal in gamma band (30-250 Hz) |

| Two-Step Decoding Procedure [36] | Prefrontal LFP & MUA | Real-time attentional spotlight tracking | Correlation with Behavioral Performance | Strongly improved correlation, especially for LFP | Non-human primate study; labeling of maximally informative trials |

| Transformer-Based Classifiers [37] | Text (for behavioral analogy) | Distinguishing human from AI-generated content | Accuracy / False Positive Rate | >99% accuracy, 0.2% false positive rate | Trained on billions of text documents |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [38] | Graph-structured data | General inference benchmark | Throughput | 81,404 tokens/second | MLPerf Inference v5.1 benchmark (Data Center, Offline) |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [39] | Image data (e.g., fMRI, sMRI) | Image classification and feature detection | Validation Accuracy (on generic images) | Varies by model (e.g., 71.9% to 82.9% on ImageNet) [40] | Adapted for structural neuroimaging analysis |

Analysis of Scalability and Computational Demand

Table 2: Scalability and resource requirements for neural data AI models

| Technology Category | Training Data Requirements | Computational Intensity | Inference Speed | Hardware Recommendations | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Models [37] [35] | Moderate | Low | Very Fast | Standard CPU | Limited capacity for complex, non-linear patterns in high-density neural signals. |

| Traditional Neural Networks [37] [35] | Large | Medium | Fast | Modern CPU / Mid-range GPU | Struggles with extremely long temporal sequences or hierarchical feature learning. |

| Deep Learning (CNNs, RNNs, Transformers) [37] [41] | Very Large | High | Medium to Fast | High-end GPU / Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) | High computational cost; "black box" nature can hinder clinical interpretability [39]. |

| Prefrontal LFP Decoding [36] | Task-specific, moderate size | Medium | Real-time capable | Specialized processing systems | Primarily validated in non-human primate models; translation to human data requires further testing. |

| Brain-Inspired ML Algorithms [41] | Varies by model | Medium to High | Varies | GPU-accelerated computing | Often designed for specific cognitive processes or neural coding principles. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Brain-Behavior Associations

Protocol 1: High-Resolution Attention Decoding from LFP Signals

This protocol, adapted from the study validating a novel decoding method, details the process for tracking covert visual attention from prefrontal local field potentials in real-time [36].

Workflow Diagram: Attention Decoding from LFP Signals

Methodology Details:

- Subject Preparation and Behavioral Task: Non-human primates are trained to perform a covert visual attention task without eye movements. The task involves shifting attentional focus to different spatial locations (x,y coordinates) on a screen, cued by visual stimuli [36].

- Neural Signal Acquisition: Local Field Potentials (LFP) are recorded chronically from the prefrontal cortex using multi-electrode arrays. The raw signal is sampled at a high frequency to capture broadband activity [36].

- Preprocessing and Feature Extraction:

- Signals are filtered into standard frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma).

- The study found that attention-related information was maximal in the gamma band (30-250 Hz), peaking between 60-120 Hz [36].

- Temporal features and power spectral densities are calculated from the filtered signals.

- Two-Step Decoding Procedure and Model Training:

- A machine learning classifier (e.g., support vector machine or neural network) is trained to map the extracted LFP features to the known (x,y) location of the attentional spotlight.

- A novel second step involves labeling maximally attention-informative trials during decoding. This refines the model by focusing on the most behaviorally relevant neural states, which was shown to significantly improve the correlation between the decoded locus of attention and the actual behavior [36].

- Validation: The decoded attentional locus is compared against the animal's actual behavioral performance on the task. A high correlation validates that the decoded signal is functionally relevant [36].

Protocol 2: AI for CNS Drug Discovery and Target Identification

This protocol outlines the application of AI/ML models to identify novel therapeutic targets and predict compound properties for CNS diseases, focusing on the critical step of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability prediction [34] [35].

Workflow Diagram: AI-Aided CNS Drug Discovery Pipeline

Methodology Details:

- Data Curation and Integration:

- Collect and pre-process heterogeneous datasets, including genetic and transcriptomic data from brain tissues of patients, high-throughput screening (HTS) data from compound libraries, and known drug-target interactions [34] [35].

- Use natural language processing (NLP) to extract insights from biomedical literature.

- Target Identification: Apply unsupervised learning methods (e.g., clustering) to multi-omics data to identify novel disease subtypes and associated molecular targets. Network analysis algorithms can model protein-protein interaction networks to pinpoint central nodes (proteins) dysregulated in disease [34] [35].

- Virtual Screening and QSAR: Train supervised ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks) on chemical structures and their biological activities (Structure-Activity Relationships, SAR) to rapidly screen millions of compounds in silico for binding affinity to the identified target [35].

- Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Prediction: This is a critical, specialized step for CNS drug discovery. A dedicated classifier (e.g., a Support Vector Machine or Naïve Bayes model) is trained on molecular descriptors of compounds with known BBB penetration data to filter candidates likely to reach the brain [34] [35].

- De Novo Drug Design and Optimization: Use generative models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) or autoencoders, to design novel molecular structures with desired properties (e.g., efficacy, safety, BBB permeability). Reinforcement learning can further optimize these structures for better pharmacokinetic profiles (ADME-Tox) [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for AI-driven neural data analysis

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Electrode Arrays | Chronic recording of Multi-Unit Activity (MUA) and Local Field Potentials (LFP) from multiple brain regions simultaneously. | In vivo electrophysiology in animal models for studying network dynamics [36]. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Non-invasive measurement of brain-wide functional connectivity via the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal. | Mapping large-scale human brain networks and their alterations in disease [42]. |

| Diffusion-Weighted MRI (dMRI) | Reconstruction of white-matter structural pathways (tractography) to model the structural connectome. | Linking structural connectivity to functional dynamics and cognitive deficits [42]. |

| MLPerf Benchmark Suite | Provides standardized, peer-reviewed benchmarks for evaluating the training and inference performance of AI hardware/software. | Informing the selection of computational platforms for large-scale neural network training or inference tasks [38]. |

| Public Neuroimaging Datasets | Large, curated datasets (e.g., ADNI, HCP) providing standardized neural and behavioral data for training and testing AI models. | Developing and validating new algorithms for disease classification or biomarker identification [34]. |

| Graph Analysis Software | Software tools (e.g., BrainGraph, NetworkX) for calculating graph theory metrics from brain networks (e.g., small-worldness, modularity, hubness). | Quantifying the topological organization of structural and functional brain networks [42]. |

| CHEMBL / PubChem Database | Public databases containing curated bioactivity data and chemical structures of millions of compounds. | Training QSAR and virtual screening models for drug discovery [35]. |