Validating the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab: Enhanced Ecological Validity in Neuropsychological Testing and Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) against traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological batteries.

Validating the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab: Enhanced Ecological Validity in Neuropsychological Testing and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) against traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological batteries. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of VR-based cognitive assessment, methodological approaches for implementation, strategies for troubleshooting common challenges, and rigorous comparative validation evidence. The synthesis demonstrates that immersive VR neuropsychological batteries offer superior ecological validity, enhanced participant engagement, and shorter administration times while maintaining strong psychometric properties, positioning them as transformative tools for clinical trials and biomedical research.

The Paradigm Shift: Why VR Assessment is Revolutionizing Neuropsychological Testing

The Ecological Validity Gap in Traditional Neuropsychological Assessment

Ecological validity (EV) refers to the relationship between neuropsychological test performance and an individual's real-world functioning [1]. Within clinical neuropsychology, this concept is formally conceptualized through two distinct approaches: veridicality, which is the empirical ability of a test to predict everyday functioning, and verisimilitude, which concerns the degree to which test demands resemble those encountered in daily life [2] [1]. This distinction is crucial for understanding the limitations of traditional assessment tools.

The field exhibits significant inconsistency in how ecological validity is defined and applied [1]. A systematic review found that approximately one-third of studies conceptualize EV solely as a test's predictive power (veridicality), another third combine both predictive power and task similarity (veridicality and verisimilitude), while the remaining third rely on definitions unrelated to classical concepts, such as simple face validity or the ability to discriminate between clinical populations [1]. This conceptual confusion complicates efforts to evaluate and improve the clinical utility of neuropsychological assessments.

Traditional Neuropsychological Assessment: Limitations and Ecological Validity Concerns

Traditional neuropsychological tests were predominantly developed to measure specific cognitive constructs (e.g., working memory, executive function) without primary regard for their ability to predict "functional" behavior in everyday contexts [2]. Many widely used instruments originated from experimental psychology paradigms rather than being designed specifically for clinical application. For instance, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), though commonly used to assess executive functions, was preceded by sorting measures developed from observations of brain damage effects rather than being created specifically to predict daily functioning [2]. Similarly, the Stroop test and Tower tests were initially developed for cognitive assessments in nonclinical populations and only later adopted for clinical use [2].

The ecological limitations of these traditional measures become apparent when examining their relationship to real-world outcomes. Research suggests that many neuropsychological tests demonstrate only a moderate level of ecological validity when predicting everyday cognitive functioning [3]. The strongest relationships typically emerge when the outcome measure closely corresponds to the specific cognitive domain assessed by the neuropsychological tests [3]. This moderate predictive power has significant clinical implications, as it limits clinicians' ability to make precise recommendations about patients' real-world capabilities and limitations based solely on traditional test performance.

Table: Ecological Validity Challenges of Traditional Neuropsychological Tests

| Test | Original Development Context | Primary Ecological Validity Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Adapted from sorting measures observing brain damage effects [2] | Does not predict what everyday situations require the abilities it measures [2] |

| Stroop Test | Developed for cognitive assessments in nonclinical populations [2] | Limited evidence connecting performance to real-world inhibition scenarios [2] |

| Traditional Continuous Performance Test (CPT) | Computer-based attention assessment [4] | Low ecological validity due to sterile laboratory environment lacking real-world distractors [4] |

Virtual Reality Solutions: Bridging the Ecological Validity Gap

Virtual reality (VR) technologies offer promising solutions to the ecological validity problem by creating controlled yet realistic assessment environments. VR systems are generally classified as either immersive (e.g., head-mounted displays/HMDs, Cave Automatic Virtual Environments/CAVEs) or non-immersive (e.g., desktop computers, tablets) [5] [6]. The key advantage of VR lies in its ability to combine the experimental control of laboratory measures with emotionally engaging scenarios that simulate real-world activities [2].

Several critical elements enhance the ecological validity of VR-based assessment, including presence (the illusion of being in the virtual place), plausibility (the illusion that virtual events are really happening), and embodiment (the feeling of "owning" a virtual body) [5]. These elements collectively contribute to more authentic responses during assessment, potentially eliciting brain activation patterns closer to those observed in real-world situations [5].

Table: VR Technologies for Ecologically Valid Neuropsychological Assessment

| Technology Type | Examples | Key Features | Ecological Validity Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR | Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), CAVE systems [6] | Surrounds user with 3D environment, naturalistic interaction [5] | Strong feeling of presence, realistic responses to stimuli [5] |

| Non-Immersive VR | Desktop computers, tablets, mobile phones [5] | 2D display, interaction via mouse/keyboard [5] | More accessible, maintains some experimental control [5] |

| Input Devices | Tracking devices, pointing devices, motion capture [6] | Captures user actions and movements [6] | Enables natural interaction with virtual environment [6] |

Comparative Experimental Data: Traditional vs. VR Assessment

Recent research provides compelling empirical evidence supporting the enhanced ecological validity of VR-based neuropsychological assessments compared to traditional measures. The following experimental protocols and findings highlight these advantages.

VR-Based Continuous Performance Test (CPT) Protocol

Experimental Protocol: Researchers developed an enhanced VR-based CPT program called "Pay Attention!" featuring four distinct real-life scenarios (room, library, outdoors, and café) with four difficulty levels in each location [4]. Unlike traditional CPTs that typically present only two conditions (distractor present vs. absent), this VR-based CPT incorporates varying levels of distraction, complexity of target and non-target stimuli, and inter-stimulus intervals [4]. The protocol was implemented for home-based assessment, where participants completed 1-2 blocks per day over two weeks to account for intra-individual variability [4].

Key Findings: The study demonstrated that higher commission errors were notably evident in the "very high" difficulty level featuring complex stimuli and increased distraction [4]. A significant correlation emerged between the overall distraction level and CPT accuracy, supporting the ecological validity of the assessment [4]. The multi-session, home-based approach addressed limitations of single-session laboratory testing, potentially providing a more reliable measure of real-world attention capabilities.

Audio-Visual Environment Assessment Protocol

Experimental Protocol: A within-subjects design compared in-situ, cylinder immersive VR environments, and HMD conditions across two sites (garden and indoor) [7]. The study measured perceptual, psychological restoration, and physiological parameters (heart rate/HR and electroencephalogram/EEG) [7]. Verisimilitude was assessed through questionnaire-based metrics including audio quality, video quality, immersion, and realism [7].

Key Findings: Both VR setups demonstrated ecological validity regarding audio-visual perceptive parameters [7]. For psychological restoration metrics, neither VR tool perfectly replicated the in-situ experiment, though cylindrical VR was slightly more accurate than HMDs [7]. Regarding physiological parameters, both HMDs and cylindrical VR showed potential for representing real-world conditions in terms of EEG change metrics or asymmetry features [7].

Table: Comparative Ecological Validity of Assessment Modalities

| Assessment Modality | Verisimilitude (Task Similarity to Real World) | Veridicality (Prediction of Real-World Function) | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Laboratory Tests | Low to Moderate [2] | Moderate [3] | Moderate prediction of everyday functioning [3] |

| VR-Based Assessments | High [5] [2] | Moderate to High [5] [4] | Realistic scenarios eliciting naturalistic responses [5] |

| Function-Led Tests | Variable | Higher than construct-driven tests [2] | Proceed from observable behaviors to cognitive processes [2] |

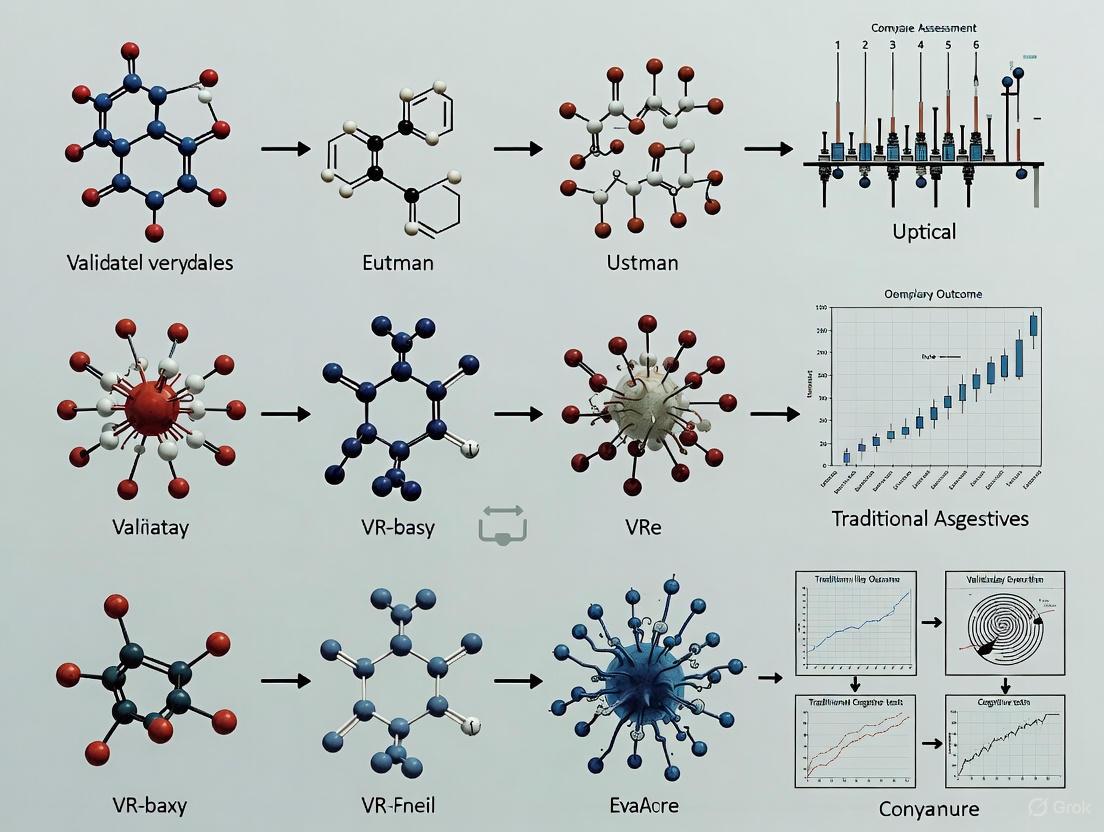

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and experimental workflow for developing ecologically valid VR-based neuropsychological assessments:

Ecological Validity Framework and VR Solution Workflow

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for VR Neuropsychological Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Provide immersive VR experience through head-worn displays [6] | Creating realistic simulated environments for assessment [5] |

| CAVE Systems | Room-scale VR environment with projections on walls [6] | High-end immersive assessment without head-worn equipment [6] |

| Eye Tracking | Input device measuring eye movements and gaze [6] | Assessing visual attention patterns in realistic scenarios [6] |

| Motion Capture Systems | Track user position and movement in real-time [6] | Naturalistic interaction with virtual environment [6] |

| Physiological Monitors | Measure HR, EEG, skin conductance during assessment [7] | Objective measurement of physiological responses [7] |

| Virtual Classroom | Specific VR environment for attention assessment [4] | Assessing ADHD with ecologically valid distractors [4] |

| Virtual Supermarkets/Malls | Simulated real-world environments [5] | Assessing executive functions in daily life contexts [5] |

The evidence clearly demonstrates that VR-based methodologies offer significant advantages for enhancing the ecological validity of neuropsychological assessment. By simulating real-world environments while maintaining experimental control, VR technologies help bridge the critical gap between laboratory test performance and everyday functioning [2]. The field is moving from purely construct-driven assessments to more function-led tests that proceed from directly observable everyday behaviors backward to examine the cognitive processes involved [2].

Future development should focus on standardizing neuropsychological and motor outcome measures across VR platforms to strengthen conclusions between studies [5]. Additionally, researchers should address technical challenges such as cybersickness, especially in clinical populations who may be more susceptible to these symptoms [5]. As VR technologies continue to become more accessible and affordable, they hold strong potential to transform neuropsychological assessment practices, ultimately providing clinicians with better tools for predicting real-world functioning and developing targeted intervention strategies.

Defining Immersive VR and its Core Applications in Healthcare

Immersive Virtual Reality (VR) is defined as a technology that creates a simulated, digital environment that replaces the user's real-world environment, typically experienced through a head-mounted display (HMD) [8]. In healthcare, this technology has evolved beyond gaming to become a critical tool for medical training, patient assessment, and therapeutic intervention [9]. The core value proposition for researchers lies in its capacity to generate highly standardized, reproducible, and ecologically valid experimental conditions while capturing rich, objective performance data [10]. This article examines the validation of VR-based assessments against traditional methods and explores its core applications, providing a comparative guide for research and development professionals.

A key concept in this domain is ecological validity—the extent to which laboratory data reflect real-world perceptions and functioning [7]. VR addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests, which often "lack similarity to real-world tasks and fail to adequately simulate the complexity of everyday activities" [11]. By allowing subjects to engage in real-world activities within controlled virtual environments, VR offers a pathway to higher ecological validity without sacrificing experimental control [11].

Validation of VR-Based Assessments: A Data-Driven Comparison

For VR to be adopted in clinical research and practice, it must demonstrate strong concurrent validity (correlation with established tests) and reliability (consistency of measurement). Recent meta-analyses and experimental studies provide compelling quantitative evidence.

Concurrent Validity for Executive Function Assessment

A 2024 meta-analysis investigating the concurrent validity between VR-based assessments and traditional neuropsychological tests revealed statistically significant correlations across all subcomponents of executive function [11]. The analysis of nine qualifying studies demonstrated VR's validity for measuring key cognitive domains, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Concurrent Validity of VR-Based Executive Function Assessments

| Executive Function Subcomponent | Correlation with Traditional Measures | Statistical Significance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Executive Function | Significant correlation | Yes (p < 0.05) | Validated as a composite measure |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Significant correlation | Yes (p < 0.05) | Comparable to traditional task switching tests |

| Attention | Significant correlation | Yes (p < 0.05) | Effectively captures sustained and selective attention |

| Inhibition | Significant correlation | Yes (p < 0.05) | Validated for response inhibition and interference control |

The meta-analysis employed rigorous methodology, searching three databases (PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect) from 2013-2023, initially identifying 1,605 articles before applying inclusion criteria [11]. The final analysis incorporated nine studies with participants ranging from children to older adults, including both healthy and clinical populations (e.g., mood disorders, ADHD, Parkinson's disease) [11]. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings even when lower-quality studies were excluded [11].

Reliability and Validity for Motor Skill Assessment

Beyond cognitive assessment, VR shows strong metric properties for measuring motor skills. A 2025 study developed and validated a VR-based sports motoric test battery, comparing it with traditional real-environment (RE) tests [12]. The study involved 32 participants completing tests twice in both RE and VR conditions, allowing for test-retest reliability and cross-method validity analysis. The results, summarized in Table 2, demonstrate VR's potential as a precise measurement tool for motor abilities.

Table 2: Reliability and Validity of VR-Based Motor Skill Assessments

| Test Type | Condition | Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | Correlation between RE and VR | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Time (Drop-Bar Test) | RE | 0.858 | r = .445 (moderate, significant) | High reliability in both conditions |

| VR | 0.888 | |||

| Jumping Ability (Jump and Reach Test) | RE | 0.944 | r = .838 (strong, significant) | Excellent reliability and high validity |

| VR | 0.886 | |||

| Complex Coordination (Parkour Test) | RE | 0.770 (mean) | Significant differences observed | Good reliability, but different behaviors in VR |

The experimental protocol for this study was designed to ensure comparability. VR tests were based on similar real-environment assessments, though some modifications were necessary to leverage VR's capabilities [12]. For instance, the parkour test in VR required participants to navigate obstacles and perform complex motor tasks, with and without a virtual opponent. The high reliability coefficients (ICC > 0.85) for reaction time and jumping ability indicate that VR can provide consistent measurements for these domains, while the moderate-to-strong correlations with real-world tests support their validity [12].

Core Healthcare Applications of Immersive VR

Medical Education and Surgical Training

VR creates risk-free environments for practicing high-stakes procedures. Leading institutions utilize platforms like SimX, which offers the largest library of medical simulations, enabling realistic team-based training for complex scenarios including trauma and pediatric care [13]. Studies demonstrate concrete outcomes: at a leading U.S. teaching hospital, VR modules for central line insertion reduced procedural errors by 28% among first-year residents compared to traditional simulation training [14].

The training efficiency gains are quantifiable: research shows that VR simulation education takes 22% less time and costs 40% less than traditional high-fidelity simulation methods [13]. Performance data further confirms that nursing students trained using immersive VR achieved higher total performance scores compared to those trained in hospital-based settings [13].

Figure 1: VR Surgical Training Workflow

Neuropsychological Assessment and Cognitive Rehabilitation

VR addresses fundamental limitations of traditional neuropsychological assessments by introducing superior ecological validity [11]. Tests like the CAVIR (Cognition Assessment in Virtual Reality) immerse participants in interactive VR kitchen scenarios to assess daily life cognitive functions, correlating significantly with traditional measures like the Trail Making Test (TMT-B) and CANTAB [11].

In therapeutic applications, XRHealth provides VR therapy for cognitive impairments, offering gamified exercises to improve focus and concentration for stroke survivors and individuals with traumatic brain injuries [13]. Clinical studies indicate these cognitive rehabilitation programs show promising results in improving memory, attention, and problem-solving skills [13].

Mental Health and Psychological Treatment

VR enables controlled delivery of evidence-based therapies. The oVRcome platform exemplifies this application, providing self-guided VR exposure therapy for specific phobias (fear of flying, heights, etc.) through a randomized controlled trial methodology [15]. Another approach comes from Oxford Medical Simulation, which combines VR with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for mental health treatment [13].

For stress and anxiety management, platforms like Novobeing create calming, interactive environments to help individuals manage emotional challenges, particularly during recovery or stressful medical procedures [13]. These applications are grounded in clinical validation, with evidence-backed designs demonstrating effectiveness in improving patient care and aiding recovery [13].

Physical Rehabilitation and Motor Recovery

VR brings engaging, personalized rehabilitation into patients' homes. The Rehago platform illustrates this application—a home-based VR rehabilitation app incorporating mirror therapy and game elements for stroke recovery [15]. Similarly, a 2022 study documented an augmented reality (AR) app that enhanced pulmonary function and feasibility of perioperative rehabilitation in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery [15].

For Parkinson's disease, research has tested the feasibility and usability of a non-immersive virtual reality tele-cognitive app in cognitive rehabilitation [15]. These applications demonstrate how VR can provide consistent, adherent-friendly rehabilitation protocols while capturing precise performance metrics unavailable in traditional clinic-based therapy.

Surgical Planning and Intraoperative Navigation

Advanced institutions are leveraging VR for sophisticated preoperative planning. At the Duke Center for Computational and Digital Health Innovations, the Randles Lab uses VR platforms like Harvis and HarVI to enable surgeons to explore 3D vascular geometries and blood flow patterns in immersive environments [8]. This approach moves beyond traditional 2D imaging, allowing clinicians to step inside a patient's anatomy to better understand and plan interventions.

Similarly, the McIntyre Lab at Duke uses VR and holographic visualization to support precise planning in deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and other neurological conditions [8]. Their Connectomic DBS approach combines high-resolution imaging and simulation to guide electrode placement tailored to individual patient neuroanatomy [8].

For intraoperative use, AR/VR technologies enable real-time 3D image overlay during surgery, allowing surgeons to accurately identify and target precise areas without looking away from the surgical field [9]. One study of 28 spinal surgeries found that AR procedures placed screws with 98% accuracy on standard performance metrics, exceeding the "clinically acceptable" rate of 90% [9].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for VR Healthcare Validation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Platforms | CAVIR (Cognition Assessment in VR) | Assessing daily life cognitive functions | Interactive VR kitchen scenario; correlates with TMT-B, CANTAB |

| Self-Developed VR Test Battery [12] | Measuring motor skills in sports performance | Assesses reaction time, jumping ability, complex coordination | |

| Therapeutic VR Platforms | XRHealth [13] | Chronic pain, anxiety, cognitive impairment research | EHR integration; home-based care; clinical outcome tracking |

| Oxford Medical Simulation [13] | Mental health intervention studies | Combines VR with CBT; home-based treatment delivery | |

| Rehago [15] | Stroke rehabilitation trials | Incorporates mirror therapy and gamification concepts | |

| Medical Training Simulators | SimX [13] | Medical education outcome studies | Largest library of medical simulations; team-based training |

| Data Collection Tools | Performance Analytics (VR-embedded) | Objective outcome measurement | Captures reaction time, movement precision, error rates |

| Physiological Sensors | Psychophysiological correlation studies | HR, EEG integration for objective response measurement |

Figure 2: VR Validation Research Framework

The validation evidence demonstrates that immersive VR has matured beyond technological novelty to become a rigorous assessment and intervention tool ready for implementation in healthcare research. Quantitative studies consistently show strong reliability and concurrent validity with traditional measures, particularly for executive function assessment and motor skill evaluation [11] [12]. The core applications—spanning medical training, neuropsychological assessment, mental health treatment, physical rehabilitation, and surgical planning—offer advantages in standardization, ecological validity, and rich data capture [9] [15] [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, VR presents opportunities to capture more sensitive, objective endpoints in clinical trials while potentially reducing variance and improving measurement consistency [10]. Future work should focus on establishing standardized validation protocols across diverse clinical populations and further demonstrating predictive validity for real-world functioning. As the technology continues to evolve, immersive VR is positioned to become an increasingly indispensable component of the healthcare research toolkit.

Virtual Reality (VR) is establishing itself as a transformative technology across healthcare, medical education, and research. Its power lies in an ability to create standardized, immersive simulations that enhance learning, personalize therapy, and streamline development processes. This guide objectively compares VR-based methodologies against traditional alternatives, supported by experimental data that validate its advantages from the lab to the clinic.

Quantitative Advantages: VR vs. Traditional Methods

The benefits of VR are being quantified across diverse fields, from education and clinical training to therapeutic interventions. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, demonstrating consistent advantages over traditional approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of VR-Based vs. Traditional Methods

| Application Area | VR-Based Intervention | Traditional Method | Key Performance Outcome | Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | VR simulations in mechanical engineering labs [16] | Traditional physical lab activities | Improvement in test scores | +20% increase in scores [16] |

| Education | VR lab-based learning for materials testing [16] | Traditional teaching methods | Improvement in scores | +14% improvement in scores [16] |

| Clinical Skills Assessment | VR-based OSCE station for emergency medicine [17] | Traditional physical OSCE station | Item Discrimination (r') | VRS: 0.40 & 0.33 (Good);Overall OSCE average: 0.30 [17] |

| Clinical Skills Assessment | VR-based OSCE station for emergency medicine [17] | Traditional physical OSCE station | Discrimination Index (D) | VRS: 0.25 & 0.26 (Mediocre);Overall OSCE average: 0.16 (Poor) [17] |

| Therapy Engagement | Immersive VR rehabilitation [18] | Conventional rehabilitation | Patient Motivation & Adherence | Improved through multi-sensory feedback and tailored, engaging tasks [18] |

Experimental Protocols: Validating VR Methodologies

The quantitative advantages presented are derived from rigorously designed experiments. The following protocols detail the methodologies used to generate this validation data.

Protocol: VR in Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs)

This randomized controlled trial evaluated the integration of a VR station (VRS) into a established medical school OSCE [17].

- Objective: To assess the feasibility, item characteristics, and student acceptance of a VRS compared to a traditional physical station (PHS) for evaluating clinical competency in emergency medicine.

- Study Design: Fifth-year medical students were randomly assigned to undertake an emergency medicine station as either a VRS or a PHS within a 10-station OSCE circuit. Two distinct clinical scenarios (septic shock and anaphylactic shock) were used to prevent content leakage [17].

- VR Platform: The STEP-VR system (version 0.13b; ThreeDee GmbH) with head-mounted displays was used to simulate complex emergencies in a virtual emergency room [17].

- Task: Students had 1 minute to read the case description, followed by 9 minutes to manage the virtual patient. The first-person perspective was transmitted to a screen for assessor evaluation [17].

- Key Measurements:

- Item Quality: Difficulty index and discrimination power (item discrimination and discrimination index) of the VRS were calculated and compared against the PHS and other stations [17].

- Feasibility: Technical functionality and integration into the exam schedule were assessed [17].

- Acceptance: Students completed a post-examination survey using a 5-point Likert scale to rate their experience [17].

Protocol: VR for Motor and Cognitive Rehabilitation

Multiple studies have investigated the efficacy of VR-based rehabilitation, particularly in neurological recovery, with a focus on patient engagement mechanisms [18] [19].

- Objective: To determine the impact of immersive VR therapy on motor function, cognitive outcomes, and patient engagement in recovery protocols.

- Theoretical Framework: The approach is often grounded in Self-Determination Theory, which posits that fulfilling psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness enhances intrinsic motivation [19].

- VR Intervention: Patients engage in task-specific exercises within customizable virtual environments. Systems can be non-immersive (tablet), semi-immersive (large displays), or fully immersive (head-mounted displays), with the level of immersion tailored to therapeutic goals [18].

- Key Therapeutic Mechanisms:

- Gamification: Integration of game elements (rewards, progress tracking) to sustain interest and adherence [19].

- Neuroplasticity: Repetitive, task-oriented practice in enriched virtual environments promotes the formation of new neural connections [19].

- Pain Distraction: Immersive environments act as a non-pharmacological analgesic by distracting patients from procedural or chronic pain [19].

- Key Measurements: Motor function scales, cognitive assessments, adherence rates, and patient-reported measures of motivation and pain perception [18] [19].

Protocol: Validation of Virtual Cohorts for In-Silico Trials

In drug and medical device development, computational models are being validated to simulate clinical trials using virtual patient cohorts [20] [21].

- Objective: To create and validate virtual cohorts that accurately represent real patient populations, enabling the partial replacement or refinement of early-phase human and animal trials.

- Workflow: The process involves generating a virtual cohort, validating its statistical similarity to a real-world patient dataset, and then deploying the validated cohort in an in-silico trial to predict drug behavior or treatment outcomes [21].

- Statistical Validation: Tools like the open-source R-statistical web application developed in the EU-Horizon SIMCor project provide a menu-driven environment for applying statistical techniques to compare virtual and real datasets [21].

- Key Measurements: Demonstrating predictive accuracy for clinical outcomes, potential for dose optimization, and quantification of time and cost savings compared to traditional trial designs [20]. For example, one predictive model for a tuberculosis regimen accurately identified the lowest effective dose, saving an estimated $90 million and sparing 700 patients from unnecessary risk [20].

Visualizing VR Validation and Application Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical pathways for validating VR systems and applying them therapeutically.

VR System Validation & Analysis Workflow

VR Therapeutic Engagement Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for VR Research

Implementing and studying VR requires a suite of technological and methodological "reagents." The table below details key components for building a robust VR research platform.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for VR Experiments

| Item | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Provides a fully immersive visual and auditory experience by blocking out the real world. Critical for high-presence simulations in training and therapy [18] [17]. |

| VR Simulation Software Platform | The core software (e.g., STEP-VR for emergencies) that generates the interactive 3D environment and defines the user's ability to interact with it [17]. |

| Biometric Sensors | Devices to measure physiological responses (e.g., heart rate, muscle tension). Used for biofeedback within the VR experience and as objective measures of engagement or stress [19]. |

| Virtual Cohort Generation & Validation Tool | Statistical software (e.g., open-source R-shiny apps) for creating and validating virtual patient populations against real-world data for in-silico trials [21]. |

| Standardized Assessment Checklists | Structured scoring rubrics for evaluators to objectively measure performance in VR scenarios (e.g., clinical checklists for OSCEs), ensuring reliability and consistency [17]. |

The application of virtual reality (VR) in healthcare has evolved from a niche research area into a rapidly expanding field, driven by technological advancements and demonstrated clinical utility. Bibliometric analysis provides a powerful, quantitative approach to map this intellectual landscape, revealing patterns of collaboration, thematic evolution, and emerging frontiers. The field has experienced exponential growth, particularly since 2016, with a notable surge in publications from 2020 onward [22] [23] [24]. This acceleration coincides with technological maturation and increased accessibility of VR hardware. The research scope has broadened from initial focuses on simulation and training to encompass diverse applications including rehabilitation, mental health therapy, surgical education, and neuropsychological assessment [22]. This analysis synthesizes bibliometric findings to characterize the current state of VR in healthcare research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured overview of productive domains, influential contributors, and validated methodological approaches.

Table 1: Key Bibliometric Indicators in VR Healthcare Research (Data from 1999-2025)

| Bibliometric Dimension | Key Findings | Data Source/Time Period |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Publication Growth | Exponential growth from 2020; over 110 annual publications in mental health VR alone [24]. | Web of Science (1999-2025) [24] |

| Most Productive Countries | United States (26.4%), United Kingdom (7.9%), Spain (6.7%) [23]. | Web of Science (1994-2021) [23] |

| Most Influential Countries (by Citation) | United States (29.8%), Canada (9.8%), United Kingdom (9.1%) [23]. | Web of Science (1994-2021) [23] |

| Leading Journals | Journal of Medical Internet Research, JMIR Serious Games, Games for Health Journal [23]. | Web of Science (1994-2021) [23] |

| Prominent Research Clusters | Virtual reality, exposure therapy, mild cognitive impairment, psychosis, serious games [24]. | CiteSpace Analysis (1999-2025) [24] |

| Key Application Areas | Surgical training, pain management & mental health therapy, rehabilitation, medical education [22] [25]. | Thematic & Bibliometric Analysis [22] [25] |

Methodological Approaches in Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric studies in this field employ rigorous, reproducible methodologies to analyze large volumes of scholarly data. The typical process involves:

- Data Collection: Researchers primarily extract data from the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, a leading database for scientific literature, using targeted title searches for terms like "virtual reality" OR "VR" combined with health-related categories [22] [23] [24]. This approach ensures the retrieved publications are centrally focused on VR.

- Analysis Tools: Studies utilize specialized software such as BibExcel, HistCite, and VOSviewer for performance analysis and science mapping [23]. More advanced tools like CiteSpace are employed to conduct temporal analysis, co-word analysis, and co-citation analysis, which help identify pivotal knowledge nodes and conceptual frameworks [24].

- Key Metrics: The core bibliometric indicators include productivity (number of publications) and impact (number of citations) for countries, institutions, journals, and authors. Keyword co-occurrence analysis is used to identify research themes and trends, while collaboration network analysis maps the relationships between researchers and institutions [22] [23].

Key Research Trends and Domain Clusters

Bibliometric analyses reveal that VR healthcare research has consolidated into several well-defined, interconnected thematic clusters.

Major Research Domains and Applications

The intellectual structure of the field, as identified through keyword and cluster analysis, shows a progression from foundational technology to specific clinical applications.

Figure 1: Knowledge Domain Clusters in VR Healthcare Research. This network illustrates the primary research themes emerging from bibliometric cluster analysis, showing how core VR technology supports diverse clinical and educational applications. MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment [24].

Mental Health Applications: This represents one of the most established clusters, with exposure therapy for conditions like PTSD and anxiety disorders being a primary focus [24]. Research has expanded to include virtual reality, exposure therapy, skin conductance, mild cognitive impairment, psychosis, augmented reality, and serious game as main research clusters [24]. The University of London, King's College London, and Harvard University are leading institutional hubs in this domain [24].

Medical Education and Surgical Training: This domain has seen significant adoption, with VR increasingly used for assessing technical clinical skills in undergraduate medical education [26]. Studies demonstrate that VR simulation is comparable to high-fidelity manikins for assessing acute clinical care skills, with no statistically significant difference in checklist scores (p = 0.918) and a strong positive correlation between the two modalities (correlation coefficient = 0.665, p = 0.005) [26].

Neuropsychological Assessment and Rehabilitation: A growing cluster focuses on developing ecologically valid assessments using immersive VR. The Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) represents a pioneering neuropsychological battery that addresses ecological validity limitations in traditional testing by simulating realistic everyday scenarios [27] [28]. This aligns with a broader function-led approach that starts with observable everyday behaviors rather than abstract cognitive constructs [29].

Geographical and Institutional Productivity

Research production and influence in VR healthcare are concentrated in specific regions and institutions, reflecting broader patterns of research investment and technological adoption.

Table 2: Leading Countries and Institutions in VR Healthcare Research

| Rank | Country | Publication Output (%) | Global Citation Share (%) | Leading Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 26.4% [23] | 29.8% [23] | Harvard University, University of California System [24] |

| 2 | United Kingdom | 7.9% [23] | 9.1% [23] | University of London, King's College London [24] |

| 3 | Spain | 6.7% [23] | - | - |

| 4 | Canada | 6.7% [23] | 9.8% [23] | - |

| 5 | China | 5.7% [23] | - | - |

Experimental Validation: VR Versus Traditional Methods

A critical research direction involves the systematic validation of VR-based assessments and interventions against established traditional methods. The following experimental protocols and findings highlight this comparative approach.

Protocol: Comparing VR with High-Fidelity Simulation for Skills Assessment

Objective: To compare two forms of simulation technology—a high-fidelity manikin (SimMan 3G) and a virtual reality system (Oxford Medical Simulation with Oculus Rift)—as assessment tools for acute clinical care skills [26].

Methodology:

- Design: Crossover study with block randomization, allowing each participant to be assessed on both technologies with different clinical scenarios (e.g., acute asthma, myocardial infarction) [26].

- Participants: Final-year medical students (n=16) familiar with both simulation modalities [26].

- Scoring: Performance was evaluated using validated assessment checklists and global assessment scores. Results were compared between technologies and with final summative examination scores [26].

Key Finding: While VR assessment scores showed no statistically significant difference from high-fidelity manikin scores (p = 0.918), neither simulation technology correlated significantly with final written or clinical examination scores [26]. This suggests that single-scenario assessment using either technology may not adequately replace comprehensive summative examinations.

Protocol: Validating VR-Based Perimetry Against Gold Standard

Objective: To evaluate the clinical validity of commercially available VR-based perimetry devices for visual field testing compared to the Humphrey Field Analyzer (HFA), the established gold standard [30].

Methodology:

- Design: Systematic review following PRISMA guidelines of 19 studies comparing VR-based visual field assessment with HFA [30].

- Devices: Included FDA-approved or CE-marked VR perimetry systems (e.g., Heru, Olleyes VisuALL, Advanced Vision Analyzer) [30].

- Outcomes: Agreement measures including mean deviation (MD) and pattern standard deviation (PSD) between VR devices and HFA [30].

Key Finding: Several VR-based perimetry systems demonstrate clinically acceptable validity compared to HFA, particularly for moderate to advanced glaucoma. However, limitations included limited dynamic range in lower-complexity devices and suboptimal performance in early-stage disease and pediatric populations [30].

Protocol: Establishing Ecological Validity of VR Neuropsychological Assessment

Objective: To compare the Virtual Environment Grocery Store (VEGS) with the California Verbal Learning Test-II (CVLT-II) for assessing episodic memory across young adults, healthy older adults, and older adults with neurocognitive impairment [29].

Methodology:

- Design: Cross-sectional study with 156 participants across three groups: young adults (n=53), healthy older adults (n=85), and older adults with neurocognitive diagnosis (n=18) [29].

- Tasks: All participants completed both the CVLT-II (traditional list-learning) and VEGS (high-distraction virtual grocery shopping) episodic memory tasks, along with the D-KEFS Color-Word Interference Test for executive function [29].

- Analysis: Correlation analysis between CVLT-II and VEGS measures, and comparison of recall performance between tests across groups [29].

Key Finding: The VEGS and CVLT-II measures were highly correlated, supporting construct validity. However, participants (particularly older adults) recalled fewer items on the VEGS than on the CVLT-II, possibly due to everyday distractors in the virtual environment increasing cognitive load [29].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Validating VR Assessments. This diagram outlines the standard methodological approach for comparing VR-based assessments against traditional tools, highlighting the parallel administration of novel and established measures [26] [29].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VR Healthcare Validation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Neuropsychological Batteries | VR Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) [27] [28] | Assesses everyday cognitive functions with enhanced ecological validity; meets NAN and AACN criteria for computerized assessment [28]. | Demonstrates pleasant testing experience without inducing cybersickness during 60-min sessions [27] [28]. |

| VR Perimetry Systems | Heru, Olleyes VisuALL, Advanced Vision Analyzer [30] | Portable visual field testing for glaucoma and neuro-ophthalmic conditions; enables telemedicine applications [30]. | Shows clinically acceptable agreement with Humphrey Field Analyzer in moderate-severe glaucoma [30]. |

| Medical Education Platforms | Oxford Medical Simulation (with Oculus Rift) [26] | Provides immersive clinical scenarios for assessing acute care skills in undergraduate medical education [26]. | Comparable to high-fidelity manikins for assessment scores (p=0.918) with strong correlation (r=0.665) [26]. |

| Validation Instruments | Virtual Reality Neuroscience Questionnaire (VRNQ) [27] | Quantitatively evaluates software quality, user experience, and VR-induced symptoms and effects (VRISE) [27]. | Used to establish low cybersickness and high user experience for VR-EAL [27]. |

| Function-Led Assessment | Virtual Environment Grocery Store (VEGS) [29] | Assesses episodic and prospective memory in ecologically valid shopping task with controlled distractors [29]. | Highly correlated with CVLT-II measures; sensitive to age-related cognitive decline [29]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

Bibliometric analysis reveals several emerging frontiers in VR healthcare research that represent promising avenues for future investigation:

- Integration with Telemedicine and Decentralized Care: VR-based assessments, particularly in visual field testing [30] and neuropsychology [27], are increasingly validated for remote administration, expanding access to underserved populations.

- Standardization and Regulatory Approval: As the field matures, there is growing emphasis on protocol standardization, rigorous validation against gold standards, and navigating regulatory pathways (FDA, CE marking) for VR medical devices [25] [30].

- Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Analytics: The integration of AI-powered analytics for real-time performance scoring [25] and personalized adaptation of therapy intensity based on physiological data [25] represents a cutting-edge innovation.

- Expansion into Diverse Clinical Populations: While early research focused on established applications, recent studies validate VR assessments in specialized populations including older adults with neurocognitive disorders [29] and pediatric patients [30].

In clinical neuroscience and neuropsychology, the ability of a test to predict real-world functioning—a property known as ecological validity—has become a critical metric for evaluation [3]. The tension between controlled laboratory assessment and real-world predictability has driven the development of two complementary theoretical frameworks: verisimilitude and veridicality [2] [31]. These approaches represent distinct methodological pathways for establishing the ecological validity of cognitive assessments, each with unique strengths and limitations.

This comparison guide examines these foundational frameworks within the context of validating virtual reality (VR) everyday assessment labs against traditional neuropsychological tests. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction is paramount when selecting cognitive assessment tools for clinical trials or evaluating the potential cognitive safety of pharmaceutical compounds [32] [33]. The emergence of immersive technologies has revitalized this theoretical discussion, offering new solutions to the longstanding challenge of bridging laboratory control with real-world relevance [2] [34].

Theoretical Foundations: Defining the Frameworks

Veridicality: Predictive Correlation with Real-World Outcomes

Veridicality represents the degree to which performance on a neuropsychological test accurately predicts specific aspects of daily functioning [2] [31]. This approach emphasizes statistical relationships between test scores and real-world behaviors, often measured through correlation coefficients with outcome measures such as vocational status, independence in daily activities, or caregiver reports [3] [2]. Veridicality does not require the test itself to resemble daily tasks—rather, it establishes predictive validity through empirical demonstration that test performance correlates with functionally important outcomes [31].

Verisimilitude: Surface Resemblance to Real-World Tasks

Verisimilitude refers to the degree to which the test materials and demands resemble those encountered in everyday life [2] [31]. Tests high in verisimilitude engage patients in tasks that mimic real-world activities, such as simulating grocery shopping, meal preparation, or route finding [2]. The theoretical foundation posits that when testing conditions closely approximate real-world contexts, the resulting performance will more readily generalize to everyday functioning [31]. This approach often incorporates multi-step tasks with dynamic stimuli that reflect the complexity of genuine daily challenges [2].

Conceptual Relationship and Distinctions

The relationship between these frameworks can be visualized as complementary pathways to the same goal of ecological validity, as illustrated below:

Experimental Validation: Methodologies and Protocols

Validation Approaches for Each Framework

Establishing ecological validity through either verisimilitude or veridicality requires distinct methodological approaches, each with characteristic strengths and limitations:

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Establishing Ecological Validity

| Framework | Primary Method | Key Measures | Data Collection Tools | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veridicality | Correlation analysis between test scores and real-world outcomes [2] [31] | Statistical correlation coefficients, predictive accuracy [3] | Questionnaires, caregiver reports, vocational status, independence measures [3] [2] | Outcome measures may not fully represent client's everyday functioning [31] |

| Verisimilitude | Task resemblance evaluation, comparison with real-world analogs [2] [31] | Participant ratings of realism, behavioral similarity, transfer of training [34] | Virtual reality simulations, real-world analog tasks, functional assessments [2] [34] | High development costs, clinician reluctance to adopt new tests [31] |

Representative Experimental Protocol: VR-EAL Validation

A representative experimental protocol for validating a virtual reality assessment battery illustrates how both frameworks can be operationalized in contemporary research [34]:

Methodological Details:

- Participants: 41 participants (21 females), including 18 gamers and 23 non-gamers [34]

- Design: Cross-over design with counterbalanced testing sessions (VR and paper-and-pencil) [34]

- Veridicality Measures: Bayesian Pearson correlation analyses between VR-EAL scores and traditional neuropsychological tests [34]

- Verisimilitude Measures: Participant ratings on ecological validity, pleasantness, and similarity to real-life tasks [34]

- Additional Metrics: Administration time, cybersickness assessment [34]

Comparative Performance Data: Traditional Tests vs. VR Assessments

Quantitative Comparisons Across Assessment Modalities

Empirical studies directly comparing traditional neuropsychological tests with emerging assessment technologies provide valuable data on how different approaches perform across key metrics:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cognitive Assessment Modalities

| Assessment Type | Ecological Validity (Participant Ratings) | Correlation with Traditional Tests | Administration Time | Participant Pleasantness Ratings | Key Supported Cognitive Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Paper-and-Pencil Tests | Lower [34] | Reference standard | Longer [34] | Lower [34] | Executive function, memory, attention, processing speed [35] [36] |

| VR-Based Assessments (VR-EAL) | Significantly higher [34] | Significant correlations with traditional equivalents [34] | Shorter [34] | Significantly higher [34] | Prospective memory, episodic memory, executive function, attention [34] |

| Computerized Flat-Screen Tests | Moderate | Moderate to strong correlations (r=0.34-0.67) [35] | Variable | Moderate | Verbal memory, visual memory, executive functions, processing speed [35] |

Specific Test Correlations and Equivalence

Research examining specific neuropsychological tests reveals variations in how different cognitive domains maintain measurement integrity across assessment modalities:

Table 3: Specific Test Equivalence Between Traditional and Digital Formats

| Cognitive Test | Correlation Between Traditional & Digital | Equivalence Status | Domain Assessed | Notable Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) | Moderate to strong [35] [36] | Equivalent [35] [36] | Verbal memory, learning | Gender effects observed (women outperform men) [35] |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | Moderate to strong [35] | Equivalent [35] | Executive function, processing speed | Digital version provides additional timing metrics [35] |

| Corsi Block-Tapping Task | Moderate [35] | Mixed equivalence [35] | Visual-spatial memory | Motor priming and interference effects noted [35] |

| Stroop Test | Moderate to strong [35] | Equivalent [35] | Executive function, inhibition | Well-validated digital equivalents [35] |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Not consistently established | Limited ecological validity [2] | Executive function | Poor predictor of everyday functioning [2] |

Applications in Clinical Drug Development

Cognitive Safety Assessment

The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly recognized the importance of sensitive cognitive assessment in clinical drug development, particularly for compounds with central nervous system penetration [32]. Both verisimilitude and veridicality frameworks inform this application:

- Phase I Trials: Early detection of drug-related cognitive adverse effects is crucial for go/no-go decisions [33]. Computerized cognitive batteries that are brief, repeatable, and sensitive to subtle impairment are essential [33].

- Regulatory Expectations: FDA guidance highlights the need for specific assessments of cognitive function for drugs with recognized CNS effects [32]. This includes measures of reaction time, divided attention, selective attention, and memory [32].

- Functional Prediction: Understanding how cognitive test results predict real-world functioning (e.g., driving ability, work productivity) is critical for risk-benefit assessments [32].

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Ecological Validity Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Relevance to Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive VR Platforms | VR-EAL (Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab) [34] | Provides ecologically valid environments for cognitive assessment | High verisimilitude approach |

| Traditional Neuropsychological Batteries | ISPOCD battery [36], Wisconsin Card Sorting Test [2] | Reference standard for cognitive assessment | Veridicality benchmark |

| Computerized Cognitive Batteries | CDR System [33], Minnemera [35] | Efficient, repeatable cognitive testing | Veridicality approach |

| Function-Led Assessments | Multiple Errands Test [2] | Direct assessment of real-world functional abilities | High verisimilitude |

| Spatial Audio Technology | First-Order Ambisonics (FOA) with head-tracking [37] | Enhances ecological validity of virtual environments | Verisimilitude enhancement |

| Outcome Measures | Questionnaires, caregiver reports, vocational status [3] [2] | Correlates with test performance for predictive validity | Veridicality assessment |

Integration and Future Directions

The distinction between verisimilitude and veridicality represents more than a theoretical debate—it fundamentally shapes assessment selection and interpretation in both clinical and research contexts. Contemporary approaches increasingly recognize the complementary value of both frameworks, leveraging technological advances to bridge the historical gap between laboratory control and ecological relevance [2] [34].

Virtual reality methodologies show particular promise for integrating both approaches by enabling the creation of standardized environments that simultaneously achieve high task resemblance (verisimilitude) while maintaining strong predictive relationships with real-world outcomes (veridicality) [34] [37]. For drug development professionals and clinical researchers, this integration offers the potential for more sensitive detection of cognitive effects and more accurate prediction of functional impacts across diverse populations and contexts.

As assessment technologies continue to evolve, the thoughtful application of both verisimilitude and veridicality frameworks will ensure that cognitive assessment remains both scientifically rigorous and clinically meaningful, ultimately enhancing our ability to understand and predict real-world functioning in healthy and clinical populations alike.

Implementation Framework: Developing and Deploying VR Assessment in Research Settings

The integration of virtual reality (VR) into assessment methodologies represents a fundamental shift in how researchers evaluate cognitive function, technical skills, and clinical competencies across diverse fields. While traditional paper-and-pencil tests and simple computer-based assessments have long been the standard, they often lack ecological validity—the ability to generalize results to real-world performance contexts. VR assessment tools create immersive, controlled environments that simulate complex real-life scenarios while maintaining rigorous experimental control. This comparison guide examines the systematic development of VR assessment tools against traditional alternatives, focusing on validation methodologies, performance metrics, and implementation frameworks that ensure scientific rigor.

The validation of these tools is particularly critical in high-stakes environments including neuropsychological assessment, medical education, and surgical skill acquisition. Contemporary research has demonstrated that when developed using structured frameworks, VR assessments can maintain the psychometric properties of traditional tests while offering enhanced engagement, better simulation of real-world environments, and more nuanced performance tracking [34] [38] [39]. This analysis provides researchers and development professionals with an evidence-based blueprint for developing, validating, and implementing VR assessment tools across scientific domains.

Systematic Development Frameworks for VR Assessments

The development of scientifically valid VR assessment tools requires structured methodologies that ensure reliability, validity, and practical applicability. Multiple research teams have established frameworks that guide this process from conceptualization through implementation.

The Verschueren Framework for Serious Games in Health

One of the most comprehensive approaches is the framework proposed by Verschueren et al. for developing serious games for health applications, which has been successfully adapted for VR assessment development [39]. This framework employs five distinct stages, each with specific focus areas and stakeholder involvement:

- Stage 1: Scientific Foundations - Establishing target audience, outcome objectives, theoretical basis, and content validation through expert review

- Stage 2: Design Foundations - Incorporating meaningful gamification elements (RECIPE: Reflection, Engagement, Choice, Information, Play, Exposition) and establishing design requirements

- Stage 3: Development - Creating the VR tool through iterative, repetitive processes with key stakeholders (software developers, content specialists, and end-users)

- Stage 4: Validation - Conducting feasibility studies assessing usability, side effects, immersion, workload, and training effectiveness

- Stage 5: Implementation - Integrating the validated tool into educational or assessment curricula

This framework was successfully implemented in the development of VR training for treating dyspnoea, resulting in a system with high usability (median System Usability Scale score of 80) and significant gains in participant confidence [39].

Methodological Protocol for Presence Factor Investigation

The systematic investigation of "presence" (the subjective experience of "being there" in a virtual environment) represents another critical framework for VR assessment development [40]. This methodology employs a two-stage procedure:

- Exploratory Investigation: Establishing empirically grounded hypotheses through open investigation of presence determinants

- Confirmatory Studies: Verifying/falsifying these hypotheses through comparative testing

This approach addresses challenges in presence research, including multifactorial ambiguity (many identified factors) and contradictory results in the literature. The development of specialized research tools that enable experimental control over external presence factors (display fidelity, interaction fidelity) while guiding the experimental process and facilitating data extraction has supported this methodology [40].

Comparative Performance Data: VR Versus Traditional Assessment

Numerous studies have conducted head-to-head comparisons between VR assessments and traditional tests, providing valuable quantitative data on their relative performance across multiple domains.

Table 1: Comparison of VR and Traditional Assessment Modalities in Medical Education

| Assessment Metric | VR-Based Assessment | Traditional Assessment | Comparative Findings | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload Perception | NASA-TLX assessment | NASA-TLX assessment | No significant difference | Medical OSCE stations [41] |

| Fairness Perception | 5-item fairness scale | 5-item fairness scale | Rated on par | Medical OSCE stations [41] |

| Realism Perception | 4-item realism scale | 4-item realism scale | Rated on par | Medical OSCE stations [41] |

| Performance Scores | Case-specific checklist | Identical checklist | Lower in VR | Medical OSCE stations [41] |

| User Satisfaction | System Usability Scale (SUS) | N/A | High (SUS: 80/100) | Emergency medicine training [39] |

| Ecological Validity | Participant ratings | Participant ratings | Significantly higher | Neuropsychological assessment [34] |

| Testing Pleasantness | Participant ratings | Participant ratings | Significantly higher | Neuropsychological assessment [34] |

| Administration Time | Time to complete battery | Time to complete battery | Shorter | Neuropsychological assessment [34] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gamified Cognitive Tasks Across Administration Modalities

| Cognitive Task | VR-Lab Performance | Desktop-Lab Performance | Desktop-Remote Performance | Traditional Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Search RT | 1.24 seconds | 1.49 seconds | 1.44 seconds | N/A [42] |

| Whack-a-Mole d-prime | 3.79 | 3.62 | 3.75 | 3-4 [42] |

| Corsi Block Span | 5.48 | 5.68 | 5.24 | 5-7 [42] |

Key Insights from Comparative Studies

The quantitative data reveals several important patterns:

- Equivalence in Perceived Experience: VR assessments achieve parity with traditional methods on key subjective metrics including workload, fairness, and realism, suggesting they are equally acceptable to users [41].

- Enhanced Ecological Validity: Multiple studies report significantly higher ecological validity for VR assessments, indicating they better simulate real-world conditions [34] [42].

- Performance Differences: The finding that medical students performed worse in VR OSCEs warrants further investigation into whether VR presents additional cognitive demands or identifies different skill sets [41].

- Modality-Dependent Effects: Reaction time measures show significant variation across administration modalities, with VR-based administration generally producing faster responses [42].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Validation Protocol for VR Neuropsychological Assessment

The validation of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) exemplifies rigorous methodology for establishing the validity of VR-based assessment tools [34] [43]. The protocol included:

- Participant Recruitment: 41 participants (21 females) including both gamers (n=18) and non-gamers (n=23) to account for potential technology familiarity confounds

- Study Design: Within-subjects design where all participants completed both immersive VR and traditional paper-and-pencil testing sessions

- Statistical Analysis: Bayesian Pearson's correlation analyses to assess construct and convergent validity between VR and traditional measures

- Comparative Metrics: Administration time, similarity to real-life tasks (ecological validity), pleasantness, and assessment accuracy

- Cybersickness Assessment: Implementation of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) to ensure participant comfort and data integrity

This validation study demonstrated that VR-EAL scores significantly correlated with equivalent scores on traditional paper-and-pencil tests while offering enhanced ecological validity and pleasantness with shorter administration times [34].

Validation Framework for Surgical Technical Aptitude Assessment

The development and validation of a VR-based technical aptitude test for surgical resident selection followed a comprehensive three-phase approach [38]:

- Phase 1: Test Development - Creation of an initial version using the Lap-X-VR laparoscopic simulator based on a blueprint developed by an educational assessment expert and three senior surgeons

- Phase 2: Expert Review - Evaluation by 30 senior surgeons who rated the test's relevance for selecting surgical residents

- Phase 3: Psychometric Validation - Administration to 152 interns to determine reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.83), task discrimination (mean discrimination = 0.5), and relationships with background variables

This systematic approach collected evidence for four main sources of validity: content, response process, internal structure, and relationships with other variables, following Messick's contemporary validity framework [38].

Visualization of VR Assessment Development Workflows

VR Assessment Development Framework

VR Assessment Validation Methodology

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for VR Assessment

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for VR Assessment Development

| Tool/Component | Primary Function | Example Implementation | Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Immersive visual/auditory presentation | Oculus Rift, HTC Vive | Established presence and immersion metrics [40] |

| VR Controllers | Natural interaction with virtual environment | Motion-tracked handheld controllers | Enhanced interaction fidelity [40] |

| Lap-X-VR Simulator | Assessment of laparoscopic technical skills | Surgical aptitude testing | High reliability (α=0.83) [38] |

| System Usability Scale (SUS) | Standardized usability assessment | 10-item questionnaire with 5-point Likert scales | Benchmarking against standard (score=68) [39] |

| NASA-TLX | Workload assessment | 6-dimensional rating scale | Comparison with traditional methods [41] |

| Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) | Cybersickness monitoring | 16 symptoms on 4-point scale | Ensuring participant comfort [41] |

| VR-EAL Battery | Neuropsychological assessment | Everyday cognitive function tasks | Enhanced ecological validity [34] |

| Presence Questionnaires | Sense of "being there" measurement | Igroup Presence Questionnaire | Key quality metric for immersion [40] |

The evidence-based comparison demonstrates that VR assessment tools, when developed using systematic frameworks, can equal or surpass traditional assessment methods on key metrics including ecological validity, user engagement, and administration efficiency. The critical differentiator for successful implementation lies in adhering to structured development methodologies that incorporate iterative stakeholder feedback, rigorous validation protocols, and comprehensive measurement of user experience.

For researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical assessment, VR tools offer particularly valuable applications in creating ecologically valid testing environments for cognitive function evaluation, surgical skill assessment, and clinical competency measurement. The documented reduction in administration time without sacrificing validity makes these tools especially promising for large-scale screening and longitudinal assessment protocols.

Future development should address the observed performance differences between VR and traditional formats, potentially refining interfaces and interaction paradigms to minimize extraneous cognitive load. Additionally, further research is needed to establish population-specific norms and cross-validate findings across diverse clinical populations. Through continued adherence to systematic development blueprints, VR assessment tools have significant potential to transform assessment practices across scientific domains.

Hardware and Software Considerations for Research-Grade VR Systems

Virtual Reality (VR) has evolved from a gaming novelty into a powerful research tool, capable of creating controlled, immersive, and ecologically valid environments for scientific study. This is particularly true in fields like cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychology, where the ecological validity of traditional testing environments—the degree to which they reflect real-world situations—has long been a limitation [27]. Immersive VR addresses this by simulating complex, real-life scenarios within the laboratory, allowing for the collection of sophisticated behavioral and cognitive data [27]. The validation of tools like the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) against traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological batteries underscores this shift, demonstrating that VR can offer enhanced ecological validity, a more pleasant testing experience, and shorter administration times without inducing cybersickness [34] [28]. For researchers embarking on this path, selecting the appropriate hardware and software is paramount to the success and integrity of their studies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current research-grade VR systems to inform these critical decisions.

Hardware Comparison: Selecting a Research HMD

The head-mounted display (HMD) is the core of any VR system. For research, key considerations extend beyond resolution and price to include integrated research-specific features like eye-tracking, the quality of pass-through cameras for augmented reality (AR) studies, and the available tracking ecosystems for full-body motion capture [44].

The table below compares the primary HMDs used in scientific labs as of 2025:

Table 1: Comparison of Research-Grade VR Head-Mounted Displays

| Headset Model | Best For | Resolution (Per Eye) | Integrated Eye Tracking | Key Research Features | Approximate Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta Quest 3 | Affordability, Standalone Use, AR [45] | 2064 x 2209 [44] | No [44] | Color pass-through cameras, wireless operation, large app ecosystem [45]. | \$500 - \$650 [44] |

| HTC Vive Focus Vision | Eye-Tracking Research [44] | 2448 x 2448 [44] | Yes, 120 Hz [44] | High-resolution color pass-through, optional face tracker, built-in eye tracking with 0.5°-1.1° accuracy [44]. | \$999 - \$1,299 [44] |

| Varjo XR-4 | High-Fidelity Visuals & Metrics [44] | 3840 x 3744 [44] | Yes, 200 Hz [44] | "Best-in-class" display, LiDAR, ultra-high-fidelity pass-through, professional-grade support [44]. | \$6,000 - \$10,000+ [44] |

| HTC Vive Pro 2 | Full Body Tracking [44] | 2448 x 2448 [44] | No [44] | Compatible with Base Station 2.0 and Vive Tracker 3.0 for high-fidelity outside-in tracking [44]. | \$1,399 (Full Kit) [44] |

For research requiring the highest fidelity full-body tracking, such as detailed biomechanical studies, the HTC Vive Pro 2 with external base stations is currently recommended. Its outside-in tracking is considered more robust than inside-out solutions for capturing complex whole-body movements [44].

Experimental Protocols: Validating VR for Research

A critical step in employing VR for research is validating that the tool reliably measures what it is intended to measure. The following workflow outlines the methodology used to validate the VR-EAL, providing a template for assessing research-grade VR systems.

Diagram 1: VR System Validation Workflow

Detailed Validation Methodology

The validation of a VR system against traditional methods follows a structured experimental protocol. The workflow for a typical cross-over design study is detailed below:

- Objective: To assess the construct and convergent validity of a VR neuropsychological battery (VR-EAL) against an extensive paper-and-pencil battery, while also evaluating ecological validity, administration time, and user experience [34].

- Participants: Recruit a sample of participants (e.g., N=41), which can include both gamers and non-gamers to control for familiarity with virtual environments. Participants attend both a VR and a traditional testing session [34].

- Study Design: A crossover design is often employed, where each participant completes both the VR and the traditional assessment, acting as their own control to minimize inter-participant variability [46]. Block randomization is used to determine the order in which participants experience the two conditions [46].

- Measures and Analysis:

- Correlation Analysis: VR-EAL scores are statistically correlated with equivalent scores from the paper-and-pencil tests to assess convergent validity [34].

- Bayesian t-tests: These are used to compare the administration time, perceived similarity to real-life tasks (ecological validity), and pleasantness of the VR assessment versus the traditional method [34].

- User Experience Metrics: Standardized questionnaires, such as the Virtual Reality Neuroscience Questionnaire (VRNQ), are administered to appraise user experience, game mechanics, in-game assistance, and the intensity of VR-induced symptoms and effects (VRISE) [27] [28].

This protocol confirmed that the VR-EAL scores significantly correlated with traditional tests, was perceived as more ecologically valid and pleasant, and had a shorter administration time without inducing cybersickness [34].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Beyond the HMD, a functional VR research lab requires several integrated components. The selection of software, tracking systems, and rendering computers directly impacts the quality and reliability of the research data.

Table 2: Essential Components of a VR Research Lab

| Component | Function | Research-Grade Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| VR Software Suite | Platform for creating and running experiments; often includes access to raw sensor data. | Vizard VR Development + SightLab VR Pro [44] |

| Rendering Computer | High-performance PC that generates the complex graphics for the VR environment. | Nvidia GeForce RTX 5090/4080/4070 GPUs; Intel Core i7/i9 CPUs [44] |

| Motion Tracking | Captures the position and movement of the user and objects for full-body avatar embodiment. | HTC Vive Pro 2 with Base Station 2.0 and Vive Tracker 3.0 [44] |

| Biofeedback Sensors | Integrates physiological data (e.g., heart rate, EEG) with in-VR events for psychophysiological studies. | Eye tracking (built into Vive Focus Vision/Varjo XR-4), face tracking, other biofeedback [44] |

Establishing a VR lab requires a significant financial investment. A basic setup with a headset and rendering computer can start around \$2,000-\$2,500, while high-fidelity systems with projection walls or full-body tracking can range from \$20,000 to over \$1 million for a state-of-the-art CAVE system or direct-view LED wall [44].

The integration of VR into scientific research represents a paradigm shift towards more engaging and ecologically valid assessment and training tools. The validation of systems like the VR-EAL demonstrates that immersive VR can meet the rigorous criteria set by professional neuropsychological bodies [28]. When selecting hardware, researchers must align their choice with the specific demands of their study: the Meta Quest 3 for cost-effective accessibility, the HTC Vive Focus Vision for integrated eye-tracking, the Varjo XR-4 for uncompromised visual fidelity, and the HTC Vive Pro 2 for complex motion capture. As the technology continues to advance, future developments will likely focus on enhancing multi-sensory feedback, improving the realism of avatars and social interactions, and deeper integration with artificial intelligence to create even more dynamic and personalized virtual research environments [47].

Creating Culturally Relevant Virtual Environments for Diverse Populations

Virtual reality (VR) is revolutionizing cognitive assessment by offering enhanced ecological validity, immersing participants in environments that closely mimic real-world contexts [48]. This technological advancement promises more accurate evaluations of cognitive functions like working memory and psychomotor skills. However, the increasing globalization of research necessitates careful consideration of cultural relevance in VR environment design. Culturally biased assessments risk misinterpreting cultural differences as cognitive deficits, compromising data validity and excluding diverse populations from benefiting from these technological advances.