Virtual Reality as a Tool for Modulating Hippocampal Function and Spatial Navigation: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes current research on the use of virtual reality (VR) to investigate and modulate hippocampal-dependent spatial navigation and memory.

Virtual Reality as a Tool for Modulating Hippocampal Function and Spatial Navigation: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the use of virtual reality (VR) to investigate and modulate hippocampal-dependent spatial navigation and memory. It explores the foundational neural mechanisms, including the enhancement of hippocampal theta rhythms and the induction of neuroplasticity through immersive experiences. The review covers methodological advances in VR-based cognitive assessment and rehabilitation, particularly for conditions like Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease. It also addresses key challenges in optimization, such as the effects of immersion level and physical movement, and provides a comparative analysis of VR against traditional methods and real-world navigation. Finally, the article discusses the implications of these findings for future biomedical research and clinical trial design in cognitive disorders.

The Hippocampus in Virtual Space: Neural Mechanisms of Spatial Navigation

Core Concepts and Neuroanatomical Foundations

Visuospatial function represents a critical domain of cognitive ability, encompassing the brain's capacity to perceive, interpret, and adapt to spatial relationships within the environment. This complex process involves multiple integrated components including visuospatial perception, visuospatial working memory, visuospatial attention, and visuospatial executive functions [1]. These functions rely on the coordinated activity of distributed neural networks, particularly the posterior parietal cortex and visuomotor areas, which specialize in processing spatial attention, object localization in three-dimensional space, and visual motion information [1].

The hippocampus serves as the central neural structure for spatial navigation and memory processes [1]. Neuroimaging studies have consistently demonstrated that the hippocampus functions as part of an extended network that includes the parahippocampal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, dorsal striatum, and posterior parietal cortex [1]. This integrated system supports the formation of cognitive maps that enable spatial navigation and environmental representation. Recent research utilizing 7 Tesla functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revealed that the brain maintains detailed endogenous somatotopic maps during rest, which become extensively recruited during visual processing tasks, suggesting a fundamental bridge between visual and somatosensory representations [2].

Spatial navigation strategies are broadly categorized into two distinct types:

- Egocentric navigation: Uses the navigator's own position as a reference frame to determine relative object positions

- Allocentric navigation: Establishes an external coordinate system to calculate positions of navigator, destinations, and landmarks [1]

These navigation strategies exhibit differential decline in aging and neurocognitive disorders, with allocentric navigation particularly vulnerable to hippocampal deterioration [1].

Quantitative Assessment Metrics and Clinical Thresholds

Table 1: Clinically Meaningful Change Thresholds in Early Cognitive Decline

| Assessment Tool | Domain Measured | Annualized Change with MCI Onset | Confidence Interval | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR-SB | Global cognition | 0.49 points | (0.43, 0.55) | Small increase indicates meaningful decline |

| MMSE | Global cognition | -1.01 points | (-1.12, -0.91) | Decrease indicates meaningful decline |

| FAQ | Instrumental activities of daily living | 1.04 points | (0.82, 1.26) | Increase indicates functional impairment |

Source: Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) population-based data [3]

Table 2: Classical Neuropsychological Tests for Visuospatial Assessment

| Assessment Tool | Specific Function Measured | Administration Method | Scoring Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test | Visuospatial memory | Reproduction of complex geometric figure | Accuracy of reproduction |

| Clock Drawing Test | Visuospatial construction | Drawing clock face with numbers and hands | 1-4 rating based on completeness/accuracy |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | Visual scanning/processing speed | Connecting numbered/lettered dots | Time to completion |

| Corsi Block-Tapping Task | Visuospatial working memory | Spatial sequence recall | Sequence length correctly recalled |

| Brief Visuospatial Memory Test (BVMT) | Visuospatial memory | Figure reproduction from memory | Accuracy of recall |

Source: Adapted from conventional visuospatial assessment methods [1]

These quantitative metrics establish critical thresholds for identifying clinically significant decline in research contexts, particularly for evaluating interventions in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) populations. The CDR-SB (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes) demonstrates particularly sensitivity to early changes, with an increase of 0.49 points annually representing clinically meaningful deterioration [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Virtual Reality-Based Spatial Cognitive Training Protocol

A rigorously controlled investigation examined the effects of Virtual Reality-Based Spatial Cognitive Training (VR-SCT) on hippocampal function in older adults with MCI [4]. The experimental protocol implemented:

Participant Allocation:

- 56 older adults with MCI randomly allocated to experimental (EG) or waitlist control groups (CG)

- Comprehensive intervention spanning 24 supervised sessions

Assessment Methodology:

- Spatial cognition measured via Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Block Design Test (WAIS-BDT)

- Episodic memory evaluated using Seoul Verbal Learning Test (SVLT)

- Statistical analysis employing ANOVA with effect size quantification (η²)

Key Findings:

- Significant performance improvements across training sessions (p < .001)

- Experimental group demonstrated substantially greater improvement in WAIS-BDT (p < .001, η² = .667) compared to controls

- Moderate but significant enhancement in SVLT recall (p < .05, η² = .094)

- Non-significant improvement in recognition component of SVLT (p > .05, η² = .001)

This protocol demonstrates that structured VR-based spatial training can effectively target hippocampal-dependent functions, with particular efficacy for spatial cognition over verbal recall tasks [4].

Connective Field Modeling for Cross-Modal Topography

Advanced neuroimaging methodologies have been developed to map the interface between visual and somatosensory representations [2]. The experimental workflow comprises:

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- 7 Tesla fMRI data from 174 Human Connectome Project participants

- 1 hour resting-state data plus 1 hour video-watching data per participant

- Dual-source connective field modeling projecting V1 and S1 topography

Analytical Framework:

- Spatial patterns (connective fields) on source regions V1 and S1 estimated for target voxels

- Model fitting to resting-state BOLD responses to reveal endogenous sensory-topographic structure

- Translation of connective-field profiles into S1 somatotopic map positions

- Statistical thresholds: all P < 10⁻⁸, minimum Cohen's d = 0.41

Experimental Outcomes:

- Identification of multiple orderly somatotopic gradients mirroring classical somatosensory organization

- Demonstration that video watching recruits 50% (95% CI = 46-55%) more cerebral cortex than rest

- Revelation of aligned visual-somatosensory topographic maps connecting sensory reference frames [2]

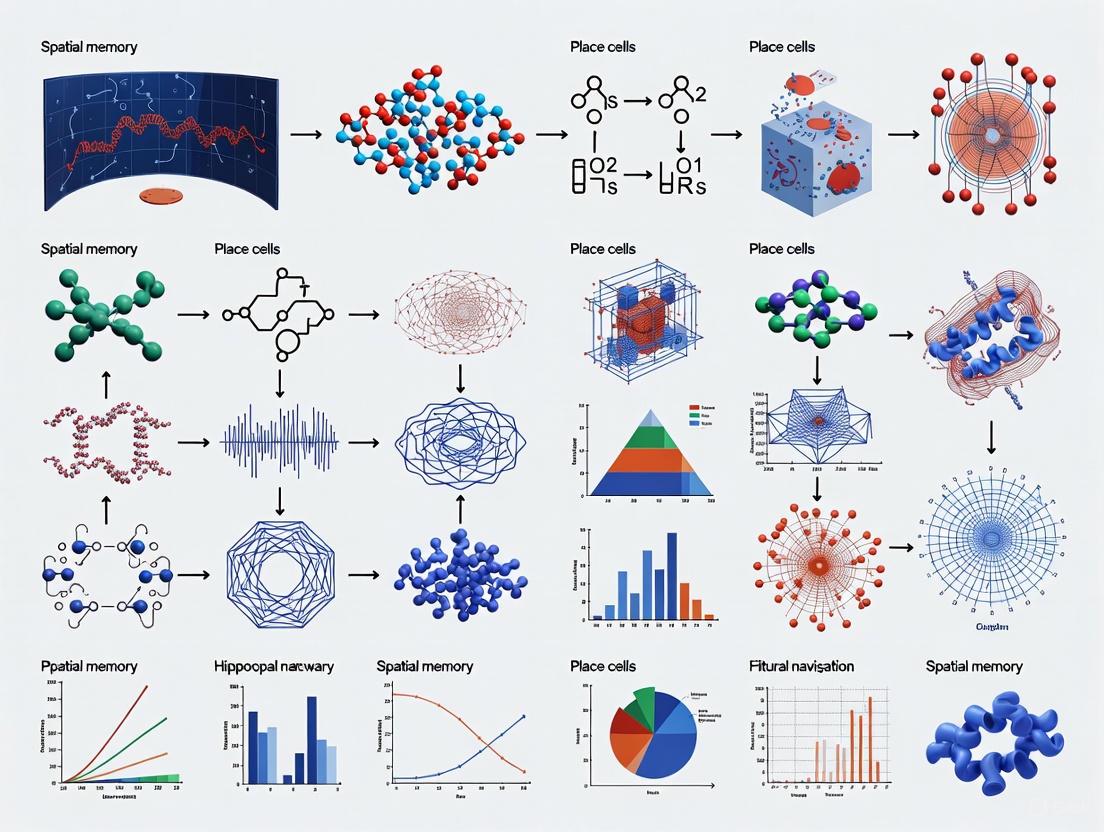

Diagram 1: Neural Pathways of Visuospatial Processing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methodologies

| Tool/Category | Specific Example | Research Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological Assessment Battery | MMSE, MoCA, MCCB | Clinical screening for visuospatial deficits | MMSE: intersecting pentagons (3/30 points); MoCA: cube drawing (3/30 points) |

| Advanced Neuroimaging | 7 Tesla fMRI with connective field modeling | Mapping visual-somatosensory topographic alignment | HCP protocols; dual-source connective field modeling of V1/S1 |

| Virtual Reality Platforms | Custom VR-SCT systems | Spatial navigation training in controlled environments | 24-session protocols; immersive environments with performance tracking |

| Computational Modeling | Somatotopic mapping algorithms | Projecting topography from source to target regions | Spatial patterns estimation from BOLD time-courses |

| Behavioral Assessment | Wayfinding and route learning tasks | Evaluating allocentric vs egocentric navigation | Real-world or virtual environment navigation with performance metrics |

Implications for Virtual Reality Research in Hippocampal Function

The integration of virtual reality methodologies into hippocampal research represents a paradigm shift in cognitive neuroscience. VR-based spatial cognitive training demonstrates significant potential for enhancing hippocampal function in impaired populations, with documented improvements in both spatial cognition and episodic memory [4]. The discovery of vicarious body maps that bridge vision and touch provides a neuroanatomical foundation for understanding how immersive virtual environments can stimulate hippocampal engagement [2].

Current research limitations center on the two-dimensional nature of traditional assessments, which lack translation processes from 2D visual information into true 3D spatial cognition [1]. Virtual reality solutions effectively address this constraint by creating ecologically valid environments that engage authentic spatial navigation circuits. Future research directions should focus on standardizing VR assessment protocols, establishing population norms for virtual navigation performance, and developing targeted interventions for specific hippocampal subfield vulnerabilities in neurodegenerative disease progression.

The alignment between visual field locations and somatotopic body maps reveals a cross-modal interface ideally situated to translate raw sensory impressions into abstract formats supporting action, social cognition, and semantic processing [2]. This mechanistic understanding provides a robust framework for developing increasingly sophisticated virtual reality interventions targeting hippocampal-dependent spatial functions in both research and clinical applications.

Spatial navigation is a fundamental cognitive process that relies on distinct neural reference frames. Egocentric navigation involves understanding space relative to one's own body (e.g., "the object is to my left"), while allocentric navigation uses world-centered coordinates independent of one's position (e.g., "the object is between the building and the tree") [5]. This technical guide examines the dissociable neural architectures, experimental methodologies, and functional implications of these spatial coding strategies, with particular relevance to virtual reality (VR) research on hippocampal function. Understanding these distinct systems is crucial for developing targeted interventions for neurological conditions and optimizing spatial memory research paradigms.

Neural Architectures and Mechanisms

Core Neural Substrates

The two navigation systems rely on partially distinct but interconnected neural networks:

Allocentric Network: Centered on the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe, this system incorporates the parahippocampal cortex, retrosplenial cortex (RSC), precuneus, and caudal intraparietal lobule (cIPL) [6] [5]. The parieto-medial temporal pathway transforms sensory information into stable, world-referenced cognitive maps [6].

Egocentric Network: Primarily involves the dorsomedial striatum (DMS), particularly the posterior division, along with the premotor cortex (PMC), frontal eye fields (FEF), and supramarginal gyrus [6] [5]. This system engages the parieto-premotor pathway for body-centered spatial computations [6].

Table 1: Neural Correlates of Spatial Navigation Strategies

| Brain Region | Egocentric Function | Allocentric Function | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Minimal involvement | Cognitive mapping, place memory | [5] [7] |

| Parahippocampal Cortex | Limited role | Egocentric bearing encoding, spatial reference | [7] |

| Dorsomedial Striatum (DMS) | Body-centered navigation, response learning | Spatial forms of navigation | [5] |

| Posterior Parietal Cortex | Multisensory body-centered integration | Spatial relationship among objects | [6] |

| Frontal Eye Fields (FEF) | Action template formation, eye movements | Attention modulation | [6] |

| Retrosplenial Cortex (RSC) | Egocentric-allocentric translation | Spatial context, heading direction | [6] |

White Matter Connectivity

Structural connectivity differences further dissociate these systems through distinct white matter pathways:

Allocentric Pathways: Depend on the posterior corona radiata (PCR) and superior corona radiata (SCR), which influence connectivity between fronto-parietal attention networks and temporal regions [6]. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) connects parietal with temporal regions critical for landmark processing [6].

Egocentric Pathways: Primarily rely on the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), which strengthens functional connectivity between posterior parietal and lateral prefrontal regions [6]. The SLF's integrity correlates with neural activity in egocentric tasks [6].

Advanced age disrupts these connections differently, with allocentric networks showing greater vulnerability to white matter degeneration in the PCR and SCR, while egocentric networks are more affected by SLF alterations [6].

Cellular-Level Representations

Single-neuron recordings in humans reveal specialized cell types for each reference frame:

Egocentric Bearing Cells (EBCs): Located abundantly in the parahippocampal cortex, these neurons encode self-centered bearings and distances toward reference points, forming vectorial representations of egocentric space [7]. EBCs show activity increases during both spatial navigation and episodic memory recall [7].

Allocentric Spatial Cells: Include place cells (hippocampus), grid cells (entorhinal cortex), and head-direction cells that collectively create world-referenced cognitive maps independent of the viewer's perspective [7].

Figure 1: Neural Pathways for Spatial Navigation. The egocentric (red) and allocentric (green) systems rely on distinct brain regions interconnected by specialized white matter tracts, with integration zones facilitating reference frame transformations.

Experimental Paradigms and Methodologies

Behavioral Tasks for Dissociating Navigation Strategies

Cross-Maze Task (Rodents)

The cross-maze paradigm effectively dissociates navigation strategies through specialized training protocols [5]:

Allocentric Training: Mice learn to find a reward at a constant position relative to extramaze cues, regardless of starting position. This requires constructing a cognitive map of the environment [5].

Egocentric Training: Mice learn to make a specific body turn (e.g., always turn left) to find the reward, independent of their absolute spatial position [5].

The critical test involves introducing a novel starting position. Allocentric-trained animals must flexibly apply their cognitive map, while egocentric-trained animals continue using the same turning response [5]. This paradigm revealed that successful allocentric navigation from novel routes activates CA1, posterior dorsomedial striatum, nucleus accumbens core, and infralimbic cortex, whereas egocentric navigation shows no significant activation in these structures [5].

Cue-to-Target Task (Humans)

Using fMRI and DTI, this paradigm examines neural activity during spatial attention tasks [6]:

Participants engage in a visual task where cues indicate whether to process target location relative to themselves (egocentric) or relative to other objects (allocentric). The task reveals that allocentric processing activates temporal-parietal pathways, while egocentric processing engages frontal-parietal networks connected via the SLF [6].

Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Approaches

Virtual environments offer controlled paradigms for studying human spatial navigation, though important considerations exist:

Stationary VR Limitations: Desktop-based virtual environments lack physical motion and idiothetic cues, potentially disrupting natural neural representations of space [8]. Rodent studies show disrupted place coding in VR environments [8].

Augmented Reality Advantages: AR paradigms combining virtual objects with real-world movement yield significantly better spatial memory performance compared to stationary VR [8]. Participants report AR tasks as easier, more immersive, and more enjoyable [8].

Neuroimaging Compatibility: VR is valuable for hippocampal function research, with studies demonstrating that VR-based spatial cognitive training improves Block Design test performance and enhances recall in older adults with mild cognitive impairment [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Behavioral and Neural Findings from Key Studies

| Study Reference | Subject Population | Task Type | Key Performance Metric | Neural Correlation/Activation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMC8831882 [6] | Older (n=24) & Younger (n=27) adults | Cue-to-target fMRI/DTI | Reaction times | Allocentric: PCR/SCR integrity; Egocentric: SLF integrity |

| S41598-020-68025-y [5] | CD1 mice | Cross-maze | Correct choices: ~90% after training | Novel allocentric route: CA1, pDMS, NacC, IL activation |

| S1041610224033933 [4] | Older adults with MCI (n=56) | VR spatial training | WAIS-BDT: p<.001, η²=.667 | Hippocampal function improvement |

| PMC12247154 [8] | Healthy adults & epilepsy patients | AR vs VR treasure hunt | Memory accuracy significantly better in walking condition | Theta oscillation increase during movement |

The Impact of Aging and Cognitive Decline

Aging differentially affects egocentric and allocentric navigation systems:

White Matter Degeneration: Age-related decline in white matter integrity disproportionately affects allocentric networks. The posterior and superior corona radiata show significant age-related differences that impact temporal lobe connectivity crucial for allocentric processing [6].

Strategic Preferences: Older adults exhibit a preference for egocentric strategies, potentially due to reduced functional connectivity between prefrontal and parietal regions supporting allocentric processing [6]. This preference may reflect compensatory mechanisms or structural decline.

Cognitive Impairment Interventions: VR-based spatial cognitive training shows promise for mild cognitive impairment, significantly improving spatial cognition and episodic memory—functions critically dependent on hippocampal integrity [4].

Technical Implementation and Research Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Research Tool | Application/Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) | Quantifies white matter integrity of pathways like SLF, PCR, SCR | Fractional anisotropy (FA) values correlate with reaction times on visuospatial tasks [6] |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Maps task-dependent neural activation during navigation paradigms | Reveals fronto-parietal attention network engagement during spatial tasks [6] |

| Zif268 Immunohistochemistry | Visualizes neural activation patterns in rodent models via immediate early gene expression | Allows high-resolution mapping across multiple brain regions in intact animals [5] |

| Virtual Reality Environments | Provides controlled spatial navigation paradigms with precise tracking | Stationary VR may disrupt natural spatial coding; AR with movement is preferred [8] |

| Single-Neuron Recording | Identifies specialized cell types (EBCs) in humans during navigation | Requires rare patients with implanted recording devices; provides unparalleled cellular resolution [7] |

Methodological Workflow

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Navigation Research. Comprehensive approach combining behavioral paradigms with multiple assessment modalities to elucidate neural mechanisms of spatial navigation.

Egocentric and allocentric navigation represent dissociable cognitive strategies supported by distinct neural architectures. The egocentric system, centered on dorsomedial striatum and fronto-parietal networks connected via the SLF, enables body-referenced navigation. The allocentric system, dependent on hippocampal-temporal networks connected via corona radiata pathways, supports cognitive mapping. These systems respond differently to aging, with allocentric networks showing greater vulnerability to age-related decline. Virtual and augmented reality technologies offer promising avenues for both investigating these navigation systems and developing interventions for cognitive impairment, though methodological considerations regarding physical movement remain crucial for valid spatial memory research.

Spatial navigation is a complex cognitive process rooted in the coordinated activity of specialized neural systems within the hippocampal formation. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms of spatial coding, focusing on the complementary roles of place cells, which generate a cognitive map of the environment, and theta rhythms, which provide a temporal framework for organizing spatial information. The integration of virtual reality (VR) with advanced electrophysiological techniques has been pivotal in elucidating the intracellular dynamics and network mechanisms underlying these processes. Research reveals that place fields are characterized by ramp-like membrane depolarization, modulated theta oscillations, and phase precession, which together support both rate and temporal coding of space [9]. Recent findings further establish that theta oscillations support a multiplexed phase code, with early phases potentially enabling retrospective encoding and late phases facilitating prospective planning [10]. Understanding these neural correlates is critical for developing novel therapeutic interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders characterized by navigation deficits.

The hippocampus functions as a central cognitive mapping system, integrating multimodal sensory inputs to represent an organism's position and orientation within space. Seminal discoveries of place cells—hippocampal pyramidal neurons that fire selectively at specific environmental locations—and the concurrent presence of a dominant theta rhythm (4-12 Hz) in the local field potential (LFP) established the foundational correlates of spatial navigation [11]. Place cells employ a rate code, where firing frequency increases substantially within a cell's "place field," and a temporal code, evidenced by theta phase precession—the progressive shifting of spike times to earlier phases of the theta cycle as an animal traverses the place field [9] [11]. This phase precession creates a compressed temporal representation of the spatial trajectory within a single theta cycle, linking the encoding of past, present, and future locations.

The emergence of virtual reality (VR) technologies has revolutionized this field of research. By enabling precise control of sensory cues and unparalleled stability for intracellular recordings during navigation behaviors, VR paradigms have become an indispensable tool for dissecting the neural mechanisms of spatial coding [9] [12]. These approaches have been successfully deployed in both rodent models and human studies, allowing researchers to bridge levels of analysis from subthreshold membrane potentials to large-scale network interactions [9] [13] [14].

Cellular Signatures of Place Cells

Intracellular recordings from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in mice navigating VR environments have revealed distinct subthreshold dynamics that define the place field. The following table summarizes the key intracellular signatures identified during in-field activity.

Table 1: Intracellular Signatures of Hippocampal Place Cells

| Signature | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric Ramp Depolarization | A slow, ramp-like increase in the baseline membrane potential, often beginning before spike initiation and reaching up to ~10 mV [9]. | Creates a permissive state for firing; may reflect integrated synaptic input driving the rate code [9]. |

| Increased Theta Oscillation Amplitude | The amplitude of intracellular theta-frequency (6-10 Hz) membrane potential oscillations is enhanced within the place field [9]. | Enhances cellular excitability and contributes to the temporal structuring of output spikes. |

| Intracellular Theta Phase Precession | The phase of the intracellular theta oscillation precesses relative to the extracellular LFP theta rhythm as the animal moves through the field [9]. | Directly underlies the temporal code of spike time phase precession, representing distance traveled. |

These intracellular dynamics are not merely correlates but are mechanistic components of place cell activity. The ramp depolarization elevates the average membrane potential, while the amplified theta oscillations provide a rhythmic scaffold that dictates the precise timing of action potentials. Spikes occur preferentially on the ascending phase of these intracellular oscillations, which themselves precess relative to the global LFP theta, thereby generating the phenomenon of spike time phase precession [9].

Theta Rhythms and Phase Precession

Theta oscillations are not a monolithic signal but a complex temporal scaffold that organizes hippocampal computation. The phenomenon of theta phase precession is a quintessential example of this organization.

Characteristics of Phase Precession

As an animal moves through a place field, the timing of a place cell's spikes shifts to progressively earlier phases of the LFP theta cycle [11]. Quantitatively, studies in VR show a phase shift of -72.6 ± 47.7 degrees between the entry and exit of the place field, resulting in a negative correlation between spike phase and animal position (C = -0.17 ± 0.09) [9]. This relationship correlates better with the distance traveled through the field than with time spent, effectively creating a phase code for location [11].

Computational Models of Phase Precession

Several competing models have been proposed to explain the mechanism underlying theta phase precession. The intracellular data obtained from VR experiments has been critical in distinguishing between them.

Table 2: Computational Models of Theta Phase Precession

| Model | Core Mechanism | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Dual Oscillator Model | Interaction between a somatic oscillation at LFP theta frequency and a faster dendritic oscillation that activates in the place field. Spike timing is locked to the peaks of the resulting higher-frequency membrane potential oscillation [11]. | Intracellular data shows a MPO that increases in frequency and amplitude within the place field, with spikes fixed to the MPO peaks [9] [11]. |

| Depolarizing Ramp Model | A somatic theta oscillation is combined with a ramp-like dendritic depolarization. The increasing depolarization causes the somatic potential to cross firing threshold earlier in each successive theta cycle [11]. | The consistent observation of a ramp-like depolarization within the place field [9]. |

| Spreading Activation Model | Firing is driven by a combination of external sensory inputs and internal recurrent connections within a network of place cells with sequential place fields, with transmission delays causing phase shifts [11]. | Supported by extracellular data on network activity patterns. |

The intracellular evidence strongly supports the Dual Oscillator Model as the primary mechanism. The critical finding is that spike timing remains fixed relative to the peaks of the cell's own MPO, while the entire MPO itself precesses relative to the LFP. This indicates that phase precession is driven by an active process within the cell or its local dendrites, not merely by a shifting firing threshold due to a depolarizing ramp [9] [11].

Multiplexed Theta Phase Coding

Recent research employing cue-conflict paradigms in VR demonstrates that theta phase coding is functionally multiplexed. Theta oscillations can simultaneously support different computational functions within a single cycle [12] [10]. The late phases of theta continue to support prospective spatial representation via classic phase precession. Conversely, the early phases of theta are implicated in retrospective representation and the encoding of new associations, particularly when animals must learn new relationships between external landmark (allothetic) cues and self-motion (idiothetic) cues [10]. This multiplexing allows the hippocampus to alternate between different computational states at a sub-second scale.

Gamma Oscillations and Theta Sequence Development

Theta sequences are experience-dependent, compressed representations of behavioral trajectories that unfold within a single theta cycle. Their development is modulated by finer-timescale gamma oscillations (25-100 Hz), which interact with the theta rhythm to organize neuronal firing [15].

Fast and Slow Gamma Rhythms

Two distinct gamma bands play complementary roles:

- Fast Gamma (~65-100 Hz): Associated with input from the medial entorhinal cortex, it is thought to rapidly encode ongoing novel sensory information. A subset of place cells (FG-cells, ~23.2%) are dominantly phase-locked to fast gamma, firing near the peak of the fast gamma cycle [15].

- Slow Gamma (~25-45 Hz): Reflects input from CA3 and is involved in the integration of learned information. Place cell spiking during slow gamma exhibits strong theta phase locking but attenuated theta phase precession [15].

Coordinated Gamma Modulation in Sequence Development

The development of predictive theta sequences relies on the coordinated activity of FG-cells. These cells are crucial for the initial encoding and emergence of the sequence's sweep-ahead structure. As sequences develop, the spikes of FG-cells also exhibit slow gamma phase precession, creating mini-sequences within the theta cycle that enable highly compressed spatial representations [15]. This dynamic suggests a model where fast gamma coordinates a subgroup of cells for rapid sensory encoding, while slow gamma fine-tunes their spike timing for precise information compression, thereby facilitating memory encoding and retrieval.

Experimental Protocols in Virtual Reality

VR systems have enabled unprecedented experimental control and recording stability. The following protocol is representative of the methods used to obtain the intracellular data cited in this guide.

Virtual Reality Behavioral Setup for Rodents

- Apparatus: Head-restrained mouse/rata runs on an air-supported spherical treadmill. A toroidal screen surrounds the animal, providing a wide field of view. Visual scenes are projected via a DLP projector [9].

- Navigation Task: Animals are trained using operant conditioning (e.g., water reward) to run along a virtual linear track (e.g., 180 cm long) with distinct visual cues. Performance is measured by total distance run, running speed, and reward acquisition rate [9].

- Data Acquisition: Movements of the spherical treadmill are tracked with an optical computer mouse, which updates the visual display in closed loop [9].

Electrophysiological Recordings

- Extracellular Recordings: Acute recordings from dorsal hippocampal CA1 using tetrodes or silicon probes to identify place cells and record LFP [9].

- Intracellular Whole-Cell Recordings: A patch electrode with a long taper is mounted on a micromanipulator. The head-fixed preparation provides the mechanical stability required for prolonged (minutes to over 20 minutes) intracellular recording from identified place cells during active VR navigation [9].

Cue Conflict Paradigm

To study multimodal integration, a VR apparatus can be designed to create a conflict between the animal's actual running speed on the treadmill (idiothetic cue) and the speed of visual landmark movement on the screen (allothetic cue). This protocol allows researchers to probe how the hippocampus resolves conflicting spatial information and has revealed the disruption of spike timing at specific theta phases during maximal conflict [12] [10].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Spatial Coding Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Spherical Treadmill with Air Support | Allows head-restrained rodents to run freely in place, providing locomotor feedback for VR navigation while ensuring mechanical stability for recordings [9]. |

| Immersive Toroidal VR Display | Provides a wide, panoramic visual field critical for engaging a rodent's natural navigation systems and presenting controlled visual cues [9]. |

| High-Impedance Patch Clamp Electrodes | Enable stable intracellular whole-cell recordings from identified neurons in awake, behaving animals to measure subthreshold membrane potential dynamics [9]. |

| Tetrode/Silicon Probe Arrays | For high-density extracellular recording of spike activity from populations of neurons and simultaneous LFP acquisition [9] [15]. |

| Cue Conflict VR Software | Custom software (e.g., based on Quake2 engine) to decouple idiothetic and allothetic cues, probing neural mechanisms of multisensory integration [9] [12]. |

| Theta/Gamma Rhythm Analysis Tools | Computational pipelines for detecting oscillations and analyzing phase relationships (e.g., phase precession, phase-locking) between spikes, MPOs, and LFP [11] [15]. |

The neural correlates of spatial coding are multifaceted, spanning from the subthreshold properties of individual place cells to the coordinated rhythms of large-scale networks. The integration of virtual reality with intracellular recording has been a transformative advancement, solidifying the roles of ramp depolarization, amplified intracellular theta, and theta-gamma interactions as core mechanisms. The emerging concept of a multiplexed theta phase code reveals a sophisticated temporal logic where different phases of a single oscillation can support distinct cognitive functions—prospection versus retrospection and encoding. These findings, largely derived from controlled VR environments, provide a fundamental mechanistic framework for understanding how the brain supports navigation and memory. This knowledge not only deepens our basic understanding of hippocampal function but also establishes biomarkers and targets for developing novel therapies for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions.

This whitepaper synthesizes recent breakthroughs in understanding how Virtual Reality (VR) modulates hippocampal rhythms to enhance cognitive function. Groundbreaking research reveals that VR is a powerful non-pharmacological tool capable of boosting theta oscillations by over 50% and inducing a novel eta rhythm, findings with profound implications for therapeutic interventions in memory disorders, drug development, and spatial navigation research. The precise control offered by VR environments over an organism's perceptual experience enables targeted investigation and manipulation of the neural circuits underlying learning and memory, positioning VR as a critical technology for future neuroscience discovery and neurological treatment.

Virtual reality has transcended its origins in entertainment to become a premier tool for cognitive neuroscience, particularly for studying the hippocampal circuits essential for spatial navigation and memory. The hippocampus acts as the brain's GPS, containing neurons that encode location and exhibit a dominant theta rhythm (4-12 Hz), a oscillation critical for neuroplasticity, learning, and memory consolidation [16]. Disruptions in this rhythm are a hallmark of disorders like Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, and schizophrenia.

VR is uniquely powerful for this research because it reacts to a subject's every movement, creating a closed-loop system that dynamically modifies brain activity [16]. Unlike passive stimuli like television, immersive VR environments provide experimenters with precise control over both the external sensory landmarks and the subject's internal perception of its movement, allowing for the isolation and study of specific cognitive processes [12]. This capability frames VR not merely as a simulation technology, but as an interactive neuromodulation platform for probing the cognitive architecture of spatial navigation, which relies on the integrated contributions of hippocampal and striatal systems [17].

Neural Mechanisms: Theta Boosting and Eta Induction

Research from the Mehta Lab at UCLA has demonstrated two profound, unique effects of VR on hippocampal neurophysiology.

Theta Rhythm Enhancement

In rodent models, navigating a VR environment boosted the rhythmicity of theta oscillations by more than 50% compared to non-VR conditions [16]. This level of enhancement is unprecedented; no known pharmacological or other intervention has demonstrated such a robust effect on the theta rhythm. The precise frequency of this rhythm is crucial for brain flexibility and learning ability (neuroplasticity). The finding suggests that VR can be calibrated to "re-tune" this rhythm to its optimal frequency, offering a potential therapeutic target for conditions where it is dysregulated.

Emergence of the Eta Rhythm

Perhaps even more significant was the discovery of a novel brain rhythm, dubbed "eta," which is induced alongside theta in VR [16]. These two rhythms are not merely different in frequency; they are spatially and functionally distinct. Theta oscillations are dominant in the dendrites (the input-receiving tendrils of neurons), while the newly observed eta rhythm is dominant in the neurons' central cell bodies. This suggests that different compartments of the same neuron are processing information differently during the VR experience, a finding that opens new windows into the micro-mechanisms of learning.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of VR on Hippocampal Rhythms Based on Rodent Studies

| Brain Rhythm | Effect of VR | Magnitude of Change | Neuronal Locus | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theta Rhythm | Significant Enhancement | >50% increase in rhythmicity [16] | Dendrites | Associated with neuroplasticity & learning [16] |

| Eta Rhythm | Novel Induction | Newly discovered rhythm [16] | Soma (Cell Body) | New window into learning mechanisms [16] |

| Hippocampal Activity | Focal Suppression | ~60% of hippocampus temporarily shuts down [16] | Neural Network | Potential for treating hyper-excited states (e.g., epilepsy) [16] |

Further underscoring VR's potent effect is the finding that nearly 60% of the hippocampus temporarily shuts down during the VR experience [16]. This focal suppression, something no known drug can achieve, points to VR's potential for managing disorders characterized by neuronal hyper-excitability, such as epilepsy.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and key neural discoveries from the foundational VR experiment on rodent subjects:

Technical Requirements for Effective VR Neuromodulation

Not all VR systems are equal in their capacity to induce these neural effects. Key technical specifications are critical for creating an immersive and effective experimental or therapeutic environment.

- Immersion and Presence: The system must generate a sufficient sense of "presence"—the feeling of actually being within the virtual experience. This is achieved through a combination of technological vividness and interactivity [18].

- Real-Time Response and Low Latency: A foundational requirement is the system's ability to react to every subject movement with imperceptible delay. Any lag can cause dizziness and disorientation, breaking immersion and corrupting neural data [16].

- Stereoscopic Visuals: Widely considered the most important factor for immersion, stereoscopic imagery presented via a head-mounted display (HMD) fully engages the user's field of vision to create a 3D effect [18].

- Precise Motion Tracking: Sensors must accurately track the subject's position and translate it into seamless navigation within the virtual world. This is essential for engaging the brain's spatial navigation systems [18].

- Multisensory Integration: While visual input is primary, the inclusion of controlled auditory, tactile (haptic), and even olfactory cues can significantly enhance the sense of presence and the strength of the neuromodulatory effect [18].

Table 2: Key Components of a Preclinical VR System for Hippocampal Research

| System Component | Function & Importance | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Display (HMD) | Provides stereoscopic 3D visuals; critical for immersion [18] | Custom rodent setup with surrounding screens [16] |

| Motion Tracking System | Treads subject's physical movement; updates virtual world in real-time [16] | Treadmill with precise position sensors [16] |

| Real-Time Rendering Engine | Generates the virtual environment instantly in response to movement [16] | High-performance computer with gaming engine (e.g., Unreal Engine) [19] |

| Neural Data Acquisition | Records brain activity (LFP, spikes) concurrently with behavior [8] | Hippocampal electrodes connected to neural signal processor [8] [16] |

| Reward Delivery System | Motivates task performance and learning [16] | Automated delivery of sugar water for correct navigation [16] |

Experimental Protocols & Spatial Navigation Paradigms

The following detailed methodologies are derived from seminal studies quantifying VR's impact on spatial memory and neural coding.

Protocol: Conflict-Induced Disruption of Phase Coding (Knierim Lab)

This protocol investigates how the brain handles conflicts between internal spatial maps and external sensory cues.

- Objective: To determine how theta phase precession in the hippocampus is affected by a mismatch between an animal's internal representation of its location and external spatial landmarks [12].

- Virtual Environment: A novel VR apparatus where a rat navigates a virtual space. The experimenter can control the rat's perceived movement speed relative to the visual landmarks, creating a conflict with its actual running speed on the treadmill [12].

- Procedure:

- The animal is trained to navigate a simple VR environment for a reward.

- During testing, the experimenters induce a "cue conflict" by decoupling the visual flow from the animal's actual physical locomotion.

- Hippocampal neural firing is recorded throughout, with a focus on the timing of spikes relative to the underlying theta rhythm (phase precession) [12].

- Key Measurements:

- Firing rate and phase precession of hippocampal place cells.

- Local Field Potential (LFP) theta rhythm dynamics.

- Outcome: During periods of maximal conflict, the firing of hippocampal neurons at a specific theta phase was disrupted. This phase is associated with new learning, suggesting the network depresses spiking output during conflict to reduce interference between old and new spatial associations [12].

Protocol: Spatial Memory in Physical vs. Virtual Navigation (AR/VR Comparison)

This human-based protocol directly compares memory performance and neural signals between ambulatory and stationary VR.

- Objective: To quantify how physical movement during encoding and recall affects human spatial memory and neural representations of space, using matched AR and VR tasks [8].

- Environment: A "Treasure Hunt" object-location associative memory task implemented in two matched conditions:

- AR Condition (Ambulatory): Participants physically walk around a real conference room with virtual treasure chests and objects overlaid via an AR headset or tablet.

- VR Condition (Stationary): Participants navigate a graphically identical virtual conference room using a desktop computer, keyboard, and screen while remaining stationary [8].

- Procedure:

- Encoding Phase: Participants navigate to treasure chests, which open to reveal objects whose locations they must remember.

- Distractor Phase: A chasing task prevents memory rehearsal and moves the participant away from the last object.

- Retrieval Phase: Participants are shown each object and must indicate its remembered location.

- Feedback Phase: Participants see their accuracy and receive points [8].

- Key Measurements:

- Spatial memory accuracy (distance error between placed and actual object location).

- Participant-reported ease, immersion, and enjoyment.

- In a case study with a mobile epilepsy patient, hippocampal local field potentials (LFPs) were recorded, with a focus on theta oscillation amplitude [8].

- Outcome: Memory performance was significantly better in the walking (AR) condition. Participants also reported it was easier and more immersive. The neural case study provided evidence for a greater increase in theta amplitude during physical movement [8].

Table 3: Summary of Key Behavioral and Neural Outcomes from Featured Protocols

| Experimental Protocol | Key Behavioral/Cognitive Finding | Key Neural Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cue Conflict (Knierim Lab) | Not directly measured | Disruption of theta phase precession during cue conflict [12] | Demonstrates VR's utility for studying neural mechanisms of memory updating and conflict resolution. |

| AR vs. VR Treasure Hunt | Significantly better spatial memory with physical walking [8] | Increased amplitude of hippocampal theta oscillations during walking [8] | Highlights importance of physical movement for engaging full spatial memory network; critical for experimental design. |

| UCLA Theta/Eta Induction | Successful navigation in VR for reward | >50% boost in theta; induction of novel eta rhythm [16] | Identifies VR's unique potential to enhance and discover fundamental brain rhythms for learning. |

The logical relationship between experimental manipulations and their observed outcomes is synthesized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential hardware, software, and analytical tools required to conduct rigorous research into VR-induced neuroplasticity.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for VR Hippocampal Neuroscience

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Hardware | Provides immersive stereoscopic visuals; blocks out real-world distractions to create controlled sensory environment [18]. |

| High-Density EEG / Electrophysiology Rig | Hardware | Records brain rhythms (theta, eta) and neural spiking activity with high temporal precision during VR navigation [8] [20]. |

| Real-Time Game Engine (e.g., Unreal Engine) | Software | Renders complex, realistic virtual environments that update fluidly in response to subject movement [19]. |

| Precision Treadmill & Motion Tracker | Hardware | Translates physical locomotion into virtual navigation, allowing for control over perceived vs. actual speed [12] [16]. |

| GABA Receptor Targeting Compounds | Chemical Reagent | Used to probe mechanism; GABAergic inhibitory neurons implicated as "conductors" of VR-induced rhythms [16]. |

| Spatial Memory Task Paradigm (e.g., Treasure Hunt) | Behavioral Assay | Standardized behavioral protocol for quantifying object-location associative memory in matched VR/AR conditions [8]. |

The Impact of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease on Spatial Navigation Networks

Spatial navigation is a fundamental cognitive ability essential for daily functioning and independence. This complex process relies on a network of brain regions, including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, which create and maintain cognitive maps of our environment [21]. In aging and neurodegenerative diseases, this network is preferentially vulnerable, leading to some of the earliest and most disabling clinical symptoms. Research into these deficits has been transformed by virtual reality (VR) technologies, which provide unprecedented experimental control while maintaining ecological validity [22]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on how aging and neurodegeneration affect spatial navigation networks, with a specific focus on insights gained through VR-based research paradigms and their implications for early detection and therapeutic development.

Neural Mechanisms of Spatial Navigation Decline

Neurobiological Changes in Healthy Aging

Age-related declines in spatial navigation stem from distinct alterations within the brain's navigation circuitry. Research in animal models reveals that neurons in the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC), particularly grid cells, become less stable and less attuned to environmental context in advanced age [23]. Grid cells create a coordinate system for space, similar to longitude and latitude, and this neural map deteriorates in elderly individuals.

In studies comparing young, middle-aged, and old mice, researchers found that while all age groups could eventually learn simple reward locations, elderly animals showed significant impairment when required to rapidly switch between two similar environments—analogous to remembering where one parked in two different parking lots [23]. The neural activity in aged mice was erratic during this task, reflecting confused spatial representation. Importantly, this decline is not uniform; significant individual variability exists, with some "super-ager" animals maintaining youthful navigation abilities and neural function, suggesting age-related decline may not be inevitable [23].

Human studies corroborate these findings, indicating that older adults often navigate familiar environments effectively but struggle significantly when learning new spaces [23]. This deficit appears more related to strategic preferences than complete loss of capabilities. Contrary to the long-held hypothesis that older adults have impaired allocentric (landmark-based) navigation, recent evidence using more naturalistic VR paradigms indicates that they retain the ability to use landmark-based strategies but exhibit a stronger preference for familiar routes [24]. When provided with rich multimodal cues in immersive environments, these age differences attenuate, suggesting navigation in aging involves strategic adaptation rather than simple deficit [24].

Navigation Deficits in Neurodegenerative Disease

Spatial navigation impairment is a prominent early marker of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related dementias, often manifesting before noticeable memory symptoms [21]. The progression of AD pathology directly disrupts the structural and functional integrity of the navigation network, with early vulnerability in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus [21] [22].

Table 1: Molecular and Genetic Correlates of Navigation Decline

| Factor | Relationship to Navigation | Research Model |

|---|---|---|

| Grid cell instability | Reduced stability of spatial firing patterns in medial entorhinal cortex | Aging mouse model [23] |

| Haplin4 gene expression | Contributes to perineuronal nets surrounding neurons; may stabilize grid cell activity | RNA sequencing in mice [23] |

| Amyloid-β and tau pathology | Early accumulation in medial temporal lobe disrupts navigation network | Human Alzheimer's studies [21] [25] |

| 61-gene signature | Associated with unstable grid cell activity in aging | RNA sequencing of young vs. old mice [23] |

Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) show pronounced deficits in allocentric spatial abilities, which are associated with elevated risk of conversion to Alzheimer's disease [26]. These navigation deficits extend beyond physical wayfinding to include abstract, knowledge-based domains, reflecting a fundamental disruption of cognitive mapping capabilities [21]. Older adults with MCI perform significantly worse on objective navigation tasks compared to community-dwelling peers without cognitive impairment [26].

Table 2: Behavioral Navigation Metrics Across Clinical Populations

| Population | Key Navigation Deficits | Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Older Adults | Impaired novel environment learning; increased reliance on familiar routes | Virtual reality paradigms; real-world navigation [24] |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | Allocentric navigation deficits; object-location memory impairment | SOT; DORA; VR-based spatial memory tasks [26] [22] |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Severe disorientation; impaired path integration; getting lost in familiar environments | Real-world navigation assessment; immersive VR [21] [22] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Visuospatial deficits; impaired executive navigation functions | Computerized cognitive training; VR motor-cognitive dual tasks [25] [27] |

Experimental Approaches and Assessment Paradigms

Virtual Reality Research Methodologies

Virtual reality has revolutionized spatial navigation research by enabling precise experimental control while maintaining ecological validity. Recent systematic reviews identify two primary VR approaches: immersive VR (iVR) using head-mounted displays that fully replace real-world sensory input, and mixed reality (MR) that superimposes computer-generated elements onto the real world [22]. These technologies enable researchers to create standardized, repeatable navigation environments while capturing rich behavioral data.

Studies directly comparing physical and virtual navigation demonstrate the importance of embodiment in spatial memory formation. Participants performing spatial memory tasks showed significantly better performance when physically walking compared to stationary VR, with added benefits of increased immersion and engagement [8]. This has important implications for both research design and therapeutic applications, suggesting that incorporation of physical movement enhances ecological validity.

Table 3: Technical Specifications of Navigation Assessment Platforms

| Platform Type | Key Components | Research Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desktop VR | Standard monitor, keyboard/mouse input | Spatial Orientation Test; Directions and Orienting Assessment | High accessibility; limited sensorimotor integration [8] [26] |

| Immersive VR (iVR) | Head-mounted display, motion tracking | Treasure Hunt task; virtual maze navigation | High ecological validity; potential cybersickness [8] [22] |

| Augmented Reality (AR) | Tablet or smart glasses, real environment | Object-location associative memory tasks | Natural movement with experimental control; technical implementation complexity [8] |

| Mixed Reality (MR) | See-through displays, environmental mapping | Spatial memory assessment with real-world anchoring | Blend of physical and virtual elements; high hardware requirements [22] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Rodent Virtual Reality Navigation Paradigm

The Stanford Medicine research team developed a sophisticated VR protocol to investigate age-related changes in grid cell function [23]:

- Subjects: Mice across three age groups (young: ~3 months; middle-aged: ~13 months; old: ~22 months) corresponding to human 20-, 50-, and 75-90-year-olds

- Apparatus: Stationary spherical treadmill surrounded by screens displaying virtual environments (mouse-sized IMAX theater)

- Procedure: Slightly thirsty mice run virtual tracks seeking hidden water rewards over six days of training

- Task Variants:

- Simple track learning: Single reward location acquisition

- Context switching: Random alternation between two previously learned tracks with different reward locations

- Neural Recording: Simultaneous electrophysiological monitoring of grid cells in medial entorhinal cortex

- Analysis: Grid cell stability, spatial specificity, and context discrimination accuracy

This protocol revealed that while aged mice could eventually learn simple routes, they showed profound impairments when rapid context switching was required, paralleling difficulties older humans experience when navigating similar environments like different parking lots [23].

Human Treasure Hunt Spatial Memory Task

The Treasure Hunt task represents a validated protocol for assessing spatial memory across healthy and clinical populations [8]:

- Environment: Conference room implemented in both augmented reality (AR) and desktop VR versions

- Participants: Healthy adults and epilepsy patients with intracranial recordings

- Task Structure:

- Encoding Phase: Participants navigate to sequentially presented treasure chests at random locations, each revealing a unique object when reached

- Distractor Phase: Animated rabbit appears for participants to chase, preventing rehearsal and displacing from last object location

- Retrieval Phase: Participants recalled and navigated to each object's location when cued with the object's name and image

- Feedback Phase: Correct locations and performance scores displayed

- Experimental Conditions:

- AR condition: Physical walking with tablet-based AR interface

- VR condition: Stationary desktop VR with keyboard control

- Measures: Spatial memory accuracy, navigation efficiency, subjective experience ratings, hippocampal theta oscillations (in patients with neural recordings)

This paradigm demonstrated significantly better spatial memory performance during physical walking compared to stationary VR, highlighting the importance of embodied navigation for optimal spatial memory formation [8].

Visualization of Neural Networks and Experimental Workflows

Spatial Navigation Network and Age-Related Disruption

Experimental Workflow for Navigation Assessment

Research Reagents and Technical Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Platforms for Navigation Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Research Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Young, middle-aged, and old mice (~3, 13, 22 months) | Aging research; correlating neural activity with behavior | Roughly equivalent to human 20-, 50-, and 75-90-year-olds [23] |

| VR Platforms | Head-mounted displays (HMDs); CAVE systems; Desktop VR | Immersive navigation environments with experimental control | Varying levels of immersion; HMDs provide highest ecological validity [22] |

| AR Interfaces | Tablet-based AR; Smart glasses | Real-world navigation with virtual elements | Enables physical movement with experimental control [8] |

| Neural Recording | Electrophysiology; fMRI; EEG; Intracranial recordings | Monitoring grid cells, place cells, theta oscillations | Human intracranial recordings primarily from epilepsy patients [8] |

| Spatial Behavior Tasks | Treasure Hunt; Virtual Mazes; Object-Location Memory | Assessing specific navigation components | Treasure Hunt tests object-location associative memory [8] |

| Genetic Tools | RNA sequencing; Gene expression analysis | Identifying molecular correlates of navigation decline | Identified 61 genes associated with unstable grid cell activity [23] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Future Research

The investigation of spatial navigation networks in aging and neurodegeneration provides critical insights for therapeutic development. VR-based spatial assessments demonstrate higher diagnostic sensitivity for early Alzheimer's pathology compared to traditional cognitive tests, potentially enabling earlier intervention [22]. These technologies also offer promising rehabilitation avenues, with adaptive VR training programs that can be implemented in clinical or home settings to maintain navigation abilities and functional independence [22] [27].

Research reveals that the brain retains considerable plasticity in navigation networks throughout life. Studies demonstrate that targeted training can strengthen connections between hippocampal regions and other brain areas, even if structural volume remains unchanged [28]. This highlights the potential for cognitive training interventions to bolster network resilience against age-related decline.

Future research directions should include longitudinal studies tracking navigation decline alongside biomarker progression, development of standardized VR assessment batteries, and investigation of how genetic factors influence individual vulnerability in navigation networks. Combining immersive technologies with advanced computational approaches like machine learning may further enhance early detection and personalized intervention strategies for age-related cognitive decline [22].

Applied VR Paradigms: From Cognitive Assessment to Targeted Rehabilitation

Traditional spatial memory assessments, including paper-and-pencil tests and laboratory-based paradigms, have long served as the standard for cognitive evaluation. However, these methods often suffer from limited ecological validity, demonstrating a restricted capacity to predict real-world functioning [29]. They are typically administered in quiet, controlled environments that lack the multisensory complexity and cognitive demands inherent in daily navigation, leading to a discordance between assessed performance and actual daily living capabilities [30] [29]. The global rise in age-related neurodegenerative conditions, where spatial memory deficits are a hallmark early feature, underscores the urgent need for more sensitive and functionally relevant assessment tools [22].

Immersive technologies, particularly Virtual Reality (VR) and Mixed Reality (MR), are poised to bridge this gap. By generating controlled, replicable, and highly immersive environments that simulate real-world navigation, VR provides a platform for assessing spatial memory with a degree of ecological validity unattainable by traditional methods [30]. These platforms engage fundamental spatial memory processes, including egocentric and allocentric navigation, which are subserved by a network of brain structures, most notably the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex [30] [31]. This positions VR-based assessment as a powerful tool for probing hippocampal function in both research and clinical diagnostics, offering a more direct window into the neural substrates of spatial navigation and memory [22] [31].

Theoretical Foundations of Spatial Memory

Spatial memory is a multifaceted cognitive function enabling individuals to encode, store, and retrieve information about their environment and spatial relationships [30]. Its assessment through VR is grounded in a clear understanding of its core components and neural architecture.

Core Cognitive Processes

Spatial memory relies on several interdependent processes and strategic reference frames, which VR environments are uniquely suited to dissect [30].

Table 1: Key Processes and Reference Frames in Spatial Memory

| Process/Frame | Description |

|---|---|

| Egocentric Reference Frame | A body-centered spatial encoding strategy that uses sensory and motor information to represent object locations relative to the observer. It is action-oriented and dominant in peripersonal space [30]. |

| Allocentric Reference Frame | An external, world-centered strategy that encodes spatial information based on environmental landmarks and boundaries, independent of the observer's position. It is crucial for long-term spatial memory and map-like mental representations [30]. |

| Route Learning | The ability to encode and recall paths through environments, involving the sequential integration of landmarks, directional cues, and self-motion [30]. |

| Path Integration | An egocentric navigation process that uses self-motion cues (vestibular, proprioceptive) to continuously update one's position relative to a starting point [30]. |

| Object-Location Memory | The capacity to recall the spatial relationships between objects and their reference points, requiring the integration of both egocentric and allocentric information [30]. |

Neural Substrates and Hippocampal Function

The neural circuitry of spatial memory is a distributed but highly specialized network. The hippocampus is a central hub, encoding spatial representations through place cells that fire in specific locations [30] [31]. This is complemented by grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex, which provide a metric for space, and head-direction cells in the thalamus, which function as an internal compass [30].

Critically, the reference frames outlined above have distinct neural correlates. The posterior parietal cortex is primarily involved in egocentric processing, integrating sensory inputs for goal-directed movement. In contrast, the retrosplenial and parahippocampal cortices are key to allocentric processing, encoding stable, viewpoint-independent spatial layouts [30]. Efficient navigation requires the seamless integration and transformation of these egocentric and allocentric frames, a process facilitated by areas like the posterior parietal cortex and the retrosplenial cortex [30]. Recent theoretical developments highlight that the human hippocampus, particularly the CA3 region, functions as an attractor network capable of storing and recalling complex episodic memories, which for primates and humans often revolve around the spatial view of a scene rather than just a single body-centered location [31].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of spatial information processing from perception to memory recall, highlighting the key brain structures involved.

Current VR/MR Tools for Spatial Memory Assessment

A systematic review of recent literature reveals a variety of immersive tools being deployed for spatial memory assessment, particularly in aging and neurodegenerative populations [22]. These tools range from adaptations of classic paradigms to novel, ecologically rich scenarios.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Assessment Paradigms

The following table summarizes the primary VR-based assessment tools, their measured outcomes, and their demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity.

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of Key VR/MR Spatial Memory Assessment Tools

| Assessment Tool / Paradigm | Primary Spatial Process Measured | Key Quantitative Metrics | Diagnostic Sensitivity & Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Morris Water Maze (vMWM) | Allocentric navigation, cognitive mapping | Path length, time to target, dwell time in target quadrant | Effectively discriminates between healthy older adults and patients with MCI, correlating with hippocampal atrophy [30] [22]. |

| VR Supermarket Test | Object-location memory, route learning | Number of errors, time to complete task, sequence accuracy | Shows high ecological validity and is sensitive to the early stages of Alzheimer's disease [30]. |

| VR Route Learning Tasks | Egocentric & allocentric integration, landmark-based navigation | Navigation errors, time taken, landmark recognition accuracy | Demonstrates higher diagnostic sensitivity for detecting MCI than traditional paper-and-pencil tests [22]. |

| Immersive VR-Based Spatial Memory Battery | Path integration, spatial learning | Distance error in path integration, trial-to-trial improvement | Identifies specific impairments in individuals at risk of neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., pre-MCI) [22]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reliability and replicability, standardized protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for two key paradigms.

Virtual Morris Water Maze (vMWM) Protocol

- Objective: To assess allocentric (world-centered) spatial learning and memory by requiring participants to find a hidden platform in a virtual pool using distal cues.

- Environment: A large, circular virtual pool (e.g., 20-meter diameter) surrounded by a curtain containing distinct, distal visual cues (e.g., geometric shapes, landmarks). The platform is hidden just below the surface of the "water".

- Procedure:

- Acquisition Phase: Participants complete a series of trials (e.g., 4 trials per day for 4-5 days). Each trial starts from a different cardinal point (North, South, East, West). They must find the hidden platform using the distal cues. The trial ends when the platform is found or after a time limit (e.g., 60 seconds).

- Probe Trial: After the acquisition phase, the platform is removed. Participants navigate the pool for a set time (e.g., 60 seconds). This trial measures spatial retention and search strategy preference for the former platform location.

- Data Collection & Analysis:

- Primary Metrics: Escape latency (time to find the platform), path length, and swimming speed during acquisition.

- Probe Trial Metrics: Percentage of time spent in the target quadrant where the platform was located, number of platform location crossings, and search path heatmaps.

- Interpretation: Intact spatial learning is shown by decreasing escape latencies across trials. A strong preference for the target quadrant during the probe trial indicates successful retention of the spatial memory.

VR Supermarket Test Protocol

- Objective: To assess object-location memory and executive functions within a high-ecological shopping scenario.

- Environment: A computer-generated or 360° video-based virtual supermarket with multiple aisles and shelves containing various products.

- Procedure:

- Encoding Phase: Participants are given a shopping list (visually and/or auditorily) and are instructed to freely navigate the supermarket to familiarize themselves with the location of each item. A time limit may be imposed.

- Recall Phase: Immediately after encoding, or after a delay, participants are asked to navigate the supermarket again and "collect" the items from the list as quickly and accurately as possible.

- Data Collection & Analysis:

- Primary Metrics: Total number of correct items selected, number of errors (wrong items or locations), total time to complete the task, path efficiency, and sequence accuracy compared to an optimal route.

- Interpretation: Poor performance, characterized by more errors, longer completion times, and inefficient routes, is indicative of spatial memory and executive function deficits, commonly seen in MCI and Alzheimer's disease.

Technical Implementation and Validation

The successful deployment of VR tools hinges on careful consideration of hardware, software, and rigorous validation against established standards.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VR Spatial Memory Assessment

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example Brands/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Provides a fully immersive visual and auditory experience, enabling naturalistic head-tracking and interaction. | Oculus Quest系列, HTC Vive, Valve Index |

| VR Development Engine | Software platform for creating and rendering controlled, interactive 3D virtual environments for experiments. | Unity, Unreal Engine |

| Spatial Tracking System | Precisely tracks a user's physical movements and translates them into the virtual space for navigation metrics. | SteamVR Tracking, Oculus Insight |

| Data Analysis Pipeline | Processes raw behavioral data (e.g., head position, controller input) into quantifiable spatial performance metrics. | Custom Python/R scripts, Unity Analytics |

| Volumetric Segmentation Software | Provides quantitative measurement of hippocampal volume from structural MRI scans for neuro-correlational studies. | FreeSurfer, Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) |

Hardware and Software Considerations

The level of immersion is a critical variable. Non-immersive VR (desktop screens) offers basic control but low presence. Semi-immersive VR (large projections) provides a middle ground. For optimal ecological validity, fully-immersive VR using Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) is recommended, as it fully engages the user's sensorimotor systems [29]. Environment design is another key choice: computer-generated environments offer maximum control and customization, while 360° video-based environments provide high realism at the cost of some interactivity and control [29].

Validation and Correlation with Traditional Measures

A systematic review of 24 studies confirms a notable alignment between VR-based memory assessments and traditional neuropsychological tests, supporting their construct validity [29]. Furthermore, VR tasks often demonstrate associations with executive functions and overall cognitive performance, highlighting their capacity to capture the dynamic interplay of cognitive systems in a functionally relevant context [29]. Crucially, VR assessments have proven effective in differentiating between clinical populations, such as older adults with dementia and cognitively healthy seniors, often with greater sensitivity than traditional tests [22] [29].

A significant technical consideration in correlational studies is the measurement of hippocampal volume. Research shows that different volumetric software applications (e.g., FreeSurfer, SPM, GIF) can produce quantitatively different hippocampal volumes from the same MRI scan, making their interchangeable use problematic [32]. This underscores the necessity of using a single, consistent segmentation method within a study when relating VR behavioral data to neural substrates.

The following diagram summarizes the multi-stage workflow for developing and validating a VR-based spatial memory assessment tool.

Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

Despite their promise, the widespread adoption of VR/MR tools in spatial memory assessment faces several hurdles. A primary challenge is the lack of standardized protocols, leading to heterogeneity in tasks, metrics, and hardware, which complicates cross-study comparisons [30] [22]. Cybersickness remains a significant issue for some users, potentially confounding performance data and limiting participant pools [30] [22]. The substantial cost of high-quality VR/MR systems and the technical expertise required for development and maintenance also present barriers to accessibility [30]. Finally, as noted previously, the integration with neuroimaging biomarkers like hippocampal volumetry is complicated by significant variability across automated segmentation software [32].

Future research directions are poised to overcome these limitations. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning can enable the development of more personalized and adaptive assessments, potentially identifying subtle behavioral markers of early decline [30] [22]. Combining VR tasks with neurophysiological techniques (e.g., EEG, fNIRS) provides a richer, multi-modal understanding of the neural dynamics underlying spatial memory [30]. A critical goal is the creation of standardized, normative databases for VR-based spatial memory metrics across ages and clinical populations. Finally, future work should focus on enhancing accessibility and usability for diverse clinical populations, ensuring these advanced tools can be deployed effectively in routine care and home-based monitoring scenarios [30] [22].

Within the broader thesis on virtual reality for spatial navigation and hippocampal function research, analyzing the differential impacts of virtual reality (VR) immersion levels on cognitive outcomes is paramount. VR environments exist across a spectrum of immersive technologies, primarily categorized as fully immersive VR (typically utilizing head-mounted displays, or HMDs) and partially immersive VR (often screen-based or utilizing motion-capture systems) [33] [34]. These distinct degrees of immersion, defined by the intensity of sensory feedback and user interaction, produce measurably different effects on users' cognitive processes and neurobiological engagement [33]. Fully immersive VR can engage multiple senses, providing a multisensory experience that induces a profound sense of "being there," or presence [33]. Conversely, partially immersive VR experiences are primarily visual and auditory with more limited sensory involvement [33]. This technical analysis examines the domain-specific cognitive outcomes associated with these VR modalities, with particular emphasis on their implications for spatial navigation research and hippocampal function.

Comparative Cognitive Outcomes: A Quantitative Synthesis

The efficacy of VR-based cognitive or physical interventions is significantly modulated by the level of immersion, with distinct profiles emerging for different cognitive domains. The table below synthesizes key findings from recent meta-analyses comparing fully immersive and partially immersive VR interventions, primarily in populations with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia.

Table 1: Domain-Specific Cognitive Outcomes of Fully Immersive vs. Partially Immersive VR Interventions

| Cognitive Domain | Fully Immersive VR Efficacy | Partially Immersive VR Efficacy | Comparative Notes |

|---|---|---|---|