Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) for anxiety disorders, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) for anxiety disorders, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It synthesizes foundational theories and the evidence base for VRET, detailing its application across specific phobias, social anxiety, and PTSD. The review examines methodological protocols, practical implementation challenges, and strategies for optimization. Furthermore, it critically evaluates comparative efficacy data against traditional therapies and active control conditions, addressing the current state of validation and identifying key frontiers for future clinical research and biomedical innovation.

The Science and Evidence Base of VRET: From Theory to Clinical Reality

Application Notes: Theoretical Foundations in VR Exposure Therapy

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) has emerged as an effective treatment for anxiety disorders, with its mechanisms explained by several dominant theoretical frameworks. Emotional Processing Theory (EPT) posits that fear is represented as a cognitive structure in memory, containing information about feared stimuli, fear responses, and their meanings [1] [2]. According to this model, successful exposure therapy requires first activating this fear structure and then introducing corrective information to modify it [3] [2]. Within VRET, this translates to presenting patients with virtual representations of feared situations sufficient to elicit fear activation, followed by prolonged exposure that facilitates within-session and between-session habituation [3] [4].

While EPT has been foundational, contemporary research also recognizes other crucial mechanisms. The Inhibitory Learning Model emphasizes creating new, non-threat associations that compete with existing fear associations, primarily through expectancy violation - when a patient's expected negative outcome does not occur [3] [2]. Self-Efficacy Theory suggests exposure works by strengthening patients' belief in their ability to cope with anxiety-provoking situations [3] [1]. For researchers, understanding this multi-mechanistic framework is essential for optimizing VRET protocols and interpreting experimental outcomes.

The simulated nature of VR presents both opportunities and challenges for these mechanisms. VRET allows for fine-tuned manipulation of exposure scenarios, enabling researchers to systematically control difficulty levels [1]. However, since patients know the virtual environment isn't real, the role of expectancy violation becomes theoretically complex, as some objectively feared outcomes (e.g., actual social rejection) cannot occur in VR [4]. Despite this, VRET demonstrates clinical effectiveness, possibly because patients still experience subjective realism and can violate expectations about their own internal reactions (e.g., "I won't be able to cope") [1].

Key Mechanistic Constructs and Their Operational Definitions

Table 1: Core Mechanisms in Exposure Therapy and Their Measurement Approaches

| Mechanistic Construct | Theoretical Origin | Operational Definition | VRET-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear Activation/Emotional Engagement | Emotional Processing Theory | Elevation of subjective/physiological fear at exposure onset; necessary for memory reconsolidation [2] | VR environments must provide sufficient immersion/presence to activate fear structures [5] |

| Within-Session Extinction (Habituation) | Emotional Processing Theory | Decline of fear response within a single exposure session [2] [4] | Session duration and stimulus intensity can be precisely controlled in VR [6] |

| Between-Session Extinction (Habituation) | Emotional Processing Theory | Decline of peak fear response across multiple exposure sessions [2] | Enables tracking of fear reduction across standardized, replicable VR scenarios [3] |

| Expectancy Violation | Inhibitory Learning Model | Experience of "surprise" when expected threat does not occur during exposure [3] [2] | Limited for outcomes that cannot virtually occur; more relevant for internal/coping expectations [4] |

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Efficacy Theory | Strengthened belief in one's capability to cope with anxiety-provoking situations [3] [1] | VR success experiences build confidence through mastery of progressively challenging scenarios [1] |

Quantitative Evidence Synthesis

Recent meta-analytic evidence supports VRET's efficacy relative to control conditions and traditional in-vivo exposure. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of VRET and In-Vivo Exposure for Anxiety Disorders

| Study Focus | Comparison Groups | Effect Size Estimate | Outcome Measures | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobia & Social Anxiety [7] | VRET vs. IVET | Moderate, comparable effect sizes for both approaches | Reduction in phobia and anxiety symptoms | VRET generates positive outcomes comparable to in-vivo exposure [7] |

| Social Anxiety in Adolescents [3] | VRE vs. IVE vs. WL (Hypothesized) | Large pre-post effects (g=0.99) for CBT-based exposure [3] | SPAI-18, LSAS-avoidance, SPWSS | Both exposure modalities expected to significantly reduce symptoms vs. waitlist [3] |

| Public Speaking Anxiety [3] | Single-session VRET | Large reduction sustained at 1-3 month follow-ups | Public speaking anxiety measures | Brief VR interventions can produce durable effects for specific social fears [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and mechanisms of VR exposure versus in-vivo exposure for socially anxious adolescents.

Population: 120 adolescents (ages 12-16) with subclinical to moderate social anxiety, randomized to VRE, IVE, or waitlist control.

Session Structure (7 sessions):

- Psychoeducation and Fear Hierarchy Development: Identify 10-15 feared social situations; create individualized VR hierarchy.

- Initial Exposure Session: Begin with moderately anxiety-provoking scenarios (e.g., speaking to a small group of virtual avatars).

- Graduated Exposure Sessions: Progressively implement more challenging scenarios based on subjective units of distress (SUDS) ratings.

- Final Mastery Session: Conduct exposure to most challenging scenarios (e.g., presenting to a large, distracted audience).

Mechanism Assessments:

- Fear Activation: Peak SUDS during first 5 minutes of exposure [2]

- Within-Session Habituation: SUDS reduction from peak to end of session [2]

- Between-Session Habituation: Peak SUDS comparison across sessions [2]

- Self-Efficacy: Self-report confidence in handling social situations [3]

- Expectancy Violation: Pre-post exposure ratings of expected vs. actual outcomes [3]

Measures Timeline: Baseline, post-treatment (8 weeks), 3-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up.

Objective: To examine the feasibility and efficacy of telemedicine-based VR exposure for animal phobias.

Population: 30-60 adults with intense fear of dogs, snakes, or spiders, randomized to telemedicine-VR versus standard telemedicine.

VR Platform: Doxy.me VR clinic with animal exposure stimuli (dogs, snakes, spiders) with multiple exemplars and behavior states (idle, calm, active, aggressive) [6].

Exposure Implementation:

- Therapist Control: Therapist selects, rotates, and manipulates animals in VR environment before making visible to client.

- Graduated Exposure: Begin with static images/videos (standard TMH) or idle/calm animals (VR), progressing to active/aggressive states.

- Between-Session Practice: Clients access homework mode for self-guided exposure with full control features.

Outcome Assessment:

- Feasibility Metrics: Enrollment, retention, assessment completion, treatment fidelity.

- Clinical Outcomes: Specific phobia symptoms, anxiety, depression, therapeutic alliance, presence.

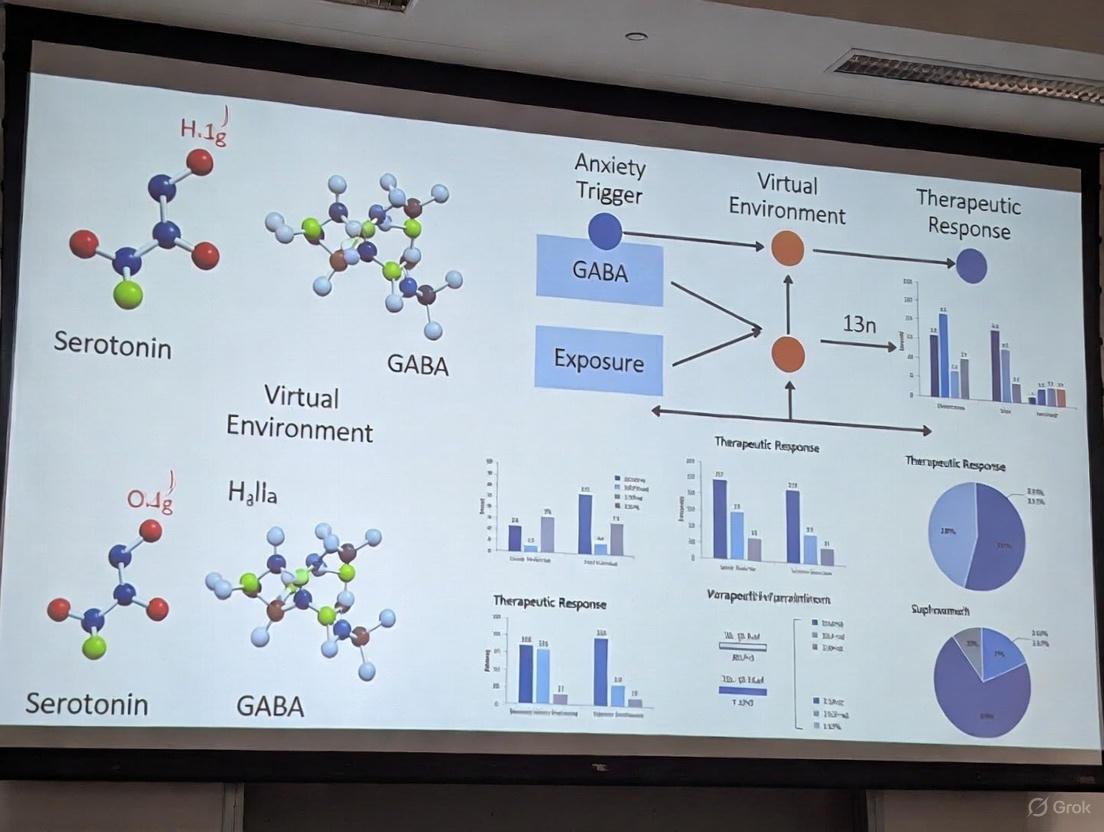

Mechanism Visualization

Theoretical Mechanisms of VR Exposure Therapy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Platforms for VRET Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Provide immersive 360° visual/auditory experience; critical for presence induction [5] | Meta Quest 2 used in telemedicine trials [6]; various commercial HMDs for clinical research |

| Doxy.me VR Platform | Telemedicine VR clinic with controlled exposure stimuli (animals, social situations) [6] | Feasibility RCT for specific phobia; enables therapist-client interaction in VR environment [6] |

| Standardized Anxiety Measures | Quantify treatment outcomes and mechanism engagement | SPAI-18, LSAS-avoidance for social anxiety [3]; SUDS for in-session fear [2] |

| Presence Questionnaires | Assess subjective sense of "being there" in virtual environment | Critical mediator of VRET effectiveness; measures realism and immersion [5] |

| Behavioral Approach Tests | Objective measure of avoidance reduction pre/post treatment | Standardized assessment of functional improvement; can be in-vivo or VR-based |

| Physiological Monitoring | Objective measure of fear activation/habituation | Heart rate variability, skin conductance, cortisol measurement complement self-report |

In the realm of virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) for anxiety disorders, the therapeutic efficacy is fundamentally governed by the ability of the virtual environment to elicit appropriate and controlled fear responses. This is achieved through the core technological principles of immersion, presence, and interactivity [8]. For researchers and clinicians, a precise understanding of these principles is not merely academic; it is essential for designing valid, effective, and reproducible digital therapeutics.

- Immersion is an objective property of the technology, referring to the extent to which a VR system can deliver a vivid, multi-sensory, and contiguous virtual environment while shutting out the physical world [9] [8].

- Presence, also known as "place illusion," is the user's subjective psychological response to the immersive system—the feeling of "being there" in the virtual environment [9] [8].

- Interactivity, or "agency," is the degree to which users can initiate and execute actions within the virtual environment and perceive plausible consequences from those actions [10] [8].

The synergy of these principles is critical in a research context. High immersion supports a strong sense of presence, which in turn is a key factor in motivating user compliance and engagement, leading to higher retention rates in clinical trials [9]. Furthermore, realistic interactivity facilitates the illusion of embodiment—the perception that one has a virtual body—which can heighten emotional intensity and improve treatment outcomes [9]. For VRET, this means that successfully inducing presence is paramount for activating the patient's core fears, thereby creating the conditions necessary for inhibitory learning and fear extinction to occur [3] [11].

Core Principles and Quantitative Definitions

A rigorous, quantitative approach to defining these principles is necessary for standardizing research methodologies and comparing findings across studies. The following table summarizes key metrics and technological factors that operationalize these concepts in experimental settings.

Table 1: Quantitative and Technological Definitions of Immersive VR Principles

| Principle | Definition | Key Technological & Subjective Metrics | Impact in VRET Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | The objective level of sensory fidelity and breadth of information delivered by the VR system [9] [8]. | - Field of View (FoV): >100° diagonal is considered wide [9].- Display Resolution: e.g., 4K (3840x2160) per eye to reduce screen-door effect.- Refresh Rate: ≥90 Hz to minimize latency and cybersickness [10].- Tracking Accuracy: 6 Degrees of Freedom (6DoF) with sub-millimeter precision [12].- Audio: High-fidelity spatial (3D) audio. | Higher immersion correlates with a greater potential for inducing presence, making the exposure scenario more potent and ecologically valid for triggering anxiety [9] [8]. |

| Presence | The subjective feeling of "being there" in the virtual environment [8]. | - Presence Questionnaire (PQ) [8].- Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) Questionnaire [8].- Physiological Measures: Heart rate, skin conductance (Galvanic Skin Response), EEG correlates of arousal [8].- Behavioral Measures: Startle responses, body sway, and other unconscious behaviors [8]. | A strong sense of presence is vital for activating the fear structure in patients with anxiety disorders, enabling corrective learning during exposure sessions [3] [11]. |

| Interactivity | The degree to which users can manipulate the virtual environment and receive feedback [10]. | - Tracking Latency: <20 ms from movement to display update is critical [10].- Haptic Fidelity: Type and bandwidth of haptic feedback (e.g., vibration, force feedback).- Physics Engine Realism: Accuracy of object manipulation and collision detection [10].- Agency Questionnaires: Subjective ratings of control over virtual actions. | Realistic interaction enhances the "plausibility illusion," making the virtual world's reactions to a patient's actions believable. This is key for violating threat expectancies (e.g., "If I speak, everyone will laugh") [10] [8]. |

The relationship between these principles can be visualized as a dependency chain where technological capabilities enable psychological experiences that drive therapeutic outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating VR Principles in Clinical Research

For research on VRET for anxiety disorders, it is essential to have standardized protocols for quantifying and validating the immersive properties of the VR environments used. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments.

Protocol: Quantifying Presence and Immersion in a VRET Public Speaking Scenario

This protocol is designed to assess the efficacy of a VR public speaking environment intended for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) research.

- Objective: To measure the levels of subjective presence and physiological correlates of anxiety elicited by a VR public speaking task.

- Hypothesis: The VR environment will induce a significant sense of presence and a physiologically measurable anxiety response comparable to anticipatory anxiety in a real-world setting.

- Materials:

- VR System: A standalone or PC-powered head-mounted display (HMD) with a minimum refresh rate of 90 Hz and 6DoF tracking.

- Software: A virtual auditorium environment with a dynamic audience capable of neutral, positive, and negative behavioral cues.

- Biosensors: Electrocardiogram (ECG) for heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV), and Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) sensors.

- Psychometric Tools: Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) Presence Questionnaire, and the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS).

- Procedure:

- Baseline (5 mins): Participant sits quietly in a neutral, empty VR environment while baseline HR, HRV, and GSR are recorded.

- VRET Task (10 mins): Participant is immersed in the virtual auditorium and instructed to deliver a 5-minute impromptu speech to a virtual audience. The audience is programmed to display subtle negative cues (e.g., looking at phones, faint heckling) after 2 minutes.

- SUDS ratings are collected at minutes 1, 3, and 5 of the speech.

- Post-Test: Immediately following the task, the participant completes the SUS questionnaire.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate mean SUS score (theoretical range 1-7, with higher scores indicating greater presence).

- Analyze physiological data: Compare mean HR and GSR during the speech task versus baseline using a paired t-test. A significant increase (p < .05) indicates successful fear activation.

Protocol: Evaluating the Impact of Embodiment on Anxiety

This experiment tests the hypothesis that a self-embodied avatar enhances the emotional intensity of a social scenario.

- Objective: To compare anxiety responses and sense of presence between a full avatar embodiment condition and a disembodied (floating camera) condition.

- Materials: As in Protocol 3.1, with the addition of a full-body avatar that is tracked in real-time via the HMD and controllers.

- Procedure:

- Design: A within-subjects, counterbalanced design.

- Condition A (Embodied): Participant sees their virtual body and hands in the auditorium. If they look down, they see a virtual torso and legs; hand movements are mirrored.

- Condition B (Disembodied): Participant is an invisible, floating presence in the room with no virtual body.

- Each condition involves a different but equivalently difficult 3-minute speech task.

- Measures: SUS Questionnaire and SUDS ratings are collected after each condition. Physiological data (GSR) is recorded throughout.

- Data Analysis: Use a repeated-measures ANOVA to compare SUS and peak GSR scores between the two conditions. A significant main effect of condition (favoring the embodied state) would support the role of embodiment in enhancing presence and emotional response [9].

The logical workflow for establishing the validity of a VRET environment, incorporating these protocols, is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Immersive VR

For research teams developing or evaluating VRET interventions, a standardized set of "research reagents"—both hardware and software—is essential for ensuring methodological consistency and reproducibility.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Immersive VR Research

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Research Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Standalone (e.g., Meta Quest 3) or PC-connected (e.g., Varjo XR-4). Must support 6DoF tracking. | The primary delivery device for the virtual environment. Determines key immersion parameters like FoV and resolution. |

| Hardware | Biosensor Array | ECG/GSR kit from vendors like Biopac Systems or Shimmer Sensing. | Provides objective, physiological data for quantifying anxiety and arousal (e.g., HR, HRV, skin conductance) during exposure. |

| Software | Game Engine | Unity (Unity Technologies) or Unreal Engine (Epic Games). | The development platform for creating and controlling custom, clinically validated VR environments and scenarios. |

| Software | Data Logging SDK | Custom SDK or lab streaming layer (LSL). | Enables synchronous recording of in-world events (e.g., audience reaction), user actions, and biosensor data for later analysis. |

| Psychometrics | Presence Questionnaire | Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) or Presence Questionnaire (PQ) [8]. | The gold-standard subjective measure for quantifying the user's feeling of "being there." |

| Psychometrics | Distress & Anxiety Scales | Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) & Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) [3]. | Validated clinical tools for measuring the primary and secondary outcomes of the VRET intervention. |

| Experimental Control | Scripted Scenario Protocol | A predefined sequence of events (e.g., audience behavior changes) with precise timings. | Ensures standardization and reproducibility of the exposure experience across all participants in a trial. |

The deliberate application of the technological principles of immersion, presence, and interactivity forms the foundation of scientifically rigorous VRET research. By systematically quantifying these elements through standardized protocols and employing a consistent toolkit of research reagents, scientists can develop digital exposures that are not only technologically sophisticated but also therapeutically potent. This methodological precision is crucial for advancing our understanding of anxiety disorders and for developing validated, effective, and replicable VR-based treatments that can stand alongside traditional therapeutic modalities. The future of clinical VR research lies in the continued refinement of these principles to create even more personalized and effective evidence-based interventions.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) has emerged as a transformative modality within the treatment landscape for anxiety disorders. By combining the established principles of exposure therapy with immersive technology, VRET creates controlled, safe, and customizable environments for patients to confront their fears. The evidence base supporting its efficacy has expanded rapidly, necessitating comprehensive and regular synthesis. This application note examines the current meta-analytic landscape, detailing the robust evidence for VRET's effectiveness, comparing it to traditional therapeutic modalities, and providing structured protocols for its implementation in clinical research settings. Recent high-quality meta-analyses consistently demonstrate that VRET produces significant reductions in anxiety symptoms, with effect sizes that are comparable to, and in some cases superior to, traditional in-vivo exposure therapy [13] [14] [7]. This document serves as a reference for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand the state of the science and the methodological standards for future investigatio

Quantitative Synthesis of the Evidence Base

The efficacy of VRET is supported by a growing number of high-quality meta-analyses. The table below consolidates key quantitative findings from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, providing a clear comparison of effect sizes across different anxiety disorders and control conditions.

Table 1: Summary of Recent Meta-Analytic Findings on VRET for Anxiety Disorders

| Meta-Analysis (Year) | Disorder Focus | Number of Studies (Participants) | Comparison Condition | Effect Size (Hedges' g or SMD) | Key Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tan et al. (2025) [13] | Social Anxiety Disorder | 17 RCTs | Waitlist comparator | Significant reduction in anxiety (Post & Follow-up) | VRET has greater efficacy than waitlist. |

| Tan et al. (2025) [13] | Social Anxiety Disorder | 17 RCTs | Other Interventions (e.g., CBT) | Similar effect (Post & Follow-up) | VRET demonstrates similar effect to other interventions. |

| Frontiers in Psychiatry (2025) [14] | Various Anxiety Disorders | 33 RCTs (3,182 participants) | Conventional Interventions | SMD = -0.95, 95% CI (-1.22, -0.69), p < 0.00001 | VR therapy significantly improved anxiety symptoms and level. |

| ScienceDirect Meta-Analysis (2025) [7] | Social Anxiety & Specific Phobia | RCTs with VRET & IVET arms | In-vivo Exposure (IVET) | Moderate effect sizes for both | VRET and IVET are equally effective. |

The data reveals a consistent pattern: VRET is statistically and clinically superior to waitlist or placebo controls and is non-inferior to traditional evidence-based treatments like in-vivo exposure and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) [13] [7]. The large, statistically significant effect size (SMD = -0.95) reported by Zeng et al. (2025) underscores the powerful effect VRET has on alleviating anxiety symptoms across a spectrum of disorders [14]. Furthermore, the combination of VRET with CBT appears to be particularly effective for symptomatic social anxiety [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for VRET Implementation

To ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility in clinical trials, the following standardized protocol outlines the core components of a VRET intervention for anxiety disorders, synthesized from multiple recent studies.

Table 2: Key Components of a Standardized VRET Intervention Protocol

| Protocol Phase | Key Activities | Duration/Frequency | Tools & Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Assessment & Preparation | Comprehensive biopsychosocial intake; diagnosis confirmation; psychoeducation on disorder and VRET rationale; informed consent; establishment of therapeutic alliance. | 2-3 sessions | Clinical interviews (e.g., ADIS-5); self-report questionnaires (e.g., LSAS, SPIN, BAI); SUDS scale explanation. |

| 2. Hierarchy Development & Customization | Collaborative creation of a fear hierarchy; selection/customization of VR scenarios to match patient-specific triggers and goals. | 1 session | Fear Hierarchy Worksheet; VR software platform with customizable environment library (e.g., audience size, scene complexity). |

| 3. Graded Exposure Sessions | Gradual, systematic exposure to fear-eliciting virtual scenarios; repetition until anxiety decreases (habituation); collaborative progression through hierarchy. | 8-12 sessions, 30-60 mins each | VR Headset (e.g., Meta Quest, HTC Vive); tailored VR environments; therapist control interface for real-time adjustments; continuous SUDS monitoring. |

| 4. Post-Session Processing & Homework | Review of exposure experience; cognitive restructuring; discussion of corrective learning; assignment of in-vivo or imaginal exposure practice. | End of each session & between sessions | Homework worksheets; behavioral experiment plans. |

| 5. Follow-up Assessment | Re-administration of baseline measures to evaluate symptom reduction and treatment gains maintenance. | Post-treatment, 3-month, 6-month | Same as baseline (e.g., LSAS, SPIN); behavioral assessment tests. |

Protocol Modifications for Specific Populations

For Adolescents: The VIRTUS trial protocol highlights adaptations for adolescent populations, including a shorter intervention (seven sessions), the use of more gamified and engaging VR content to enhance motivation, and a focus on developmental-stage-appropriate fears like speaking in class or meeting new people [3].

For Self-Guided Interventions: Emerging protocols for fully self-guided VRET, such as the 14-day smartphone-based intervention for university students, involve locked daily progression, automated reminders, and culturally tailored scenarios (e.g., classroom presentations) to ensure adherence and effectiveness without therapist guidance [15].

Signaling Pathways and Theoretical Mechanisms

The efficacy of VRET is underpinned by several well-established psychological theories of fear extinction and learning. The following diagram illustrates the primary theoretical pathways through which VRET is hypothesized to exert its therapeutic effects.

The primary mechanisms identified in contemporary research are:

- Emotional Processing Theory: VRET works by activating the fear structure in memory and promoting within- and between-session habituation, leading to a reduction in the fear response over time [3] [16].

- Inhibitory Learning Theory: This dominant model posits that VRET creates new, non-threatening memories that compete with the original fear memory. The key mechanism is expectancy violation—when the patient's feared outcome (e.g., being humiliated during a speech) does not occur, new, inhibitory learning takes place [3] [11].

- Self-Efficacy Theory: Successfully navigating challenging virtual scenarios enhances the patient's belief in their ability to cope, thereby increasing self-efficacy and reducing anxiety and avoidance behaviors [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing a rigorous VRET research program requires specific technological and assessment tools. The following table details the key components of a research-grade VRET setup.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for VRET Trials

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware | VR Headset | Standalone (e.g., Meta Quest 3) or PC-tethered (e.g., HTC Vive) | Creates immersive 3D environment for stimulus delivery. |

| Hardware | Therapist Control Interface | Tablet or laptop with dedicated software | Allows real-time control and customization of VR scenarios during sessions. |

| Hardware (Optional) | Biofeedback Devices | Heart rate monitor, galvanic skin response sensor | Provides objective, physiological data on anxiety activation and habituation. |

| Software | VRET Platform | Platforms like PsyTechVR with a library of evidence-based environments | Delivers standardized, customizable anxiety-provoking scenarios (e.g., crowds, heights). |

| Software | Assessment & Data Management System | Integrated database for patient progress tracking | Ensures fidelity to protocol and facilitates data collection for outcomes. |

| Psychometrics | Primary Outcome Measures | Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) | Quantifies change in disorder-specific symptom severity. |

| Psychometrics | Process Measures | Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) | Tracks momentary anxiety fluctuations during exposure sessions. |

Recent advancements have validated more accessible hardware, including smartphone-based VR headsets, which maintain efficacy while dramatically improving scalability and reducing costs, as demonstrated in studies with college students [15]. Furthermore, the integration of biofeedback devices is an emerging trend, allowing researchers to collect rich, multimodal data (subjective, behavioral, and physiological) on treatment processes and outcomes [17].

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of anxiety disorders, leveraging immersive technology to create controlled, replicable therapeutic environments. Within the broader thesis of optimizing VRET for anxiety disorders, understanding its disorder-specific efficacy is crucial for clinical application and future research. The evidence base, while robust for certain conditions, reveals a nuanced landscape of effectiveness across the diagnostic spectrum. This variability stems from fundamental differences in the neurobiological underpinnings of anxiety disorders, which can be categorized into fear-dominant (e.g., specific phobia, agoraphobia), mixed (e.g., panic disorder, social anxiety disorder), and anxiety-dominant (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) conditions [18]. The following application notes and protocols detail the empirical evidence and methodological frameworks for applying VRET across these disorders, providing a resource for researchers and clinical trial designers.

Efficacy Data and Comparative Outcomes

Quantitative data from meta-analyses and controlled trials provide a clear, disorder-specific breakdown of VRET's performance against both passive and active control conditions.

Table 1: VRET Efficacy Across Anxiety Disorders (vs. Waitlist/Placebo)

| Condition | Number of RCTs Included | Total N | Effect Size (Hedges' g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobias | 12 | 431 | 0.95* | [19] |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 7 | 236 | 0.97* | [19] |

| Panic Disorder | 2 | 65 | 1.03* | [19] |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | 6 | 175 | 0.57* | [19] |

Note: All effect sizes are statistically significant (p < .05) and reflect outcomes at post-treatment. Hedges' g is a measure of effect size where 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 medium, and 0.8 large.

Table 2: VRET Efficacy Compared to Active Treatments (In Vivo Exposure)

| Condition | Number of RCTs Included | Total N | Effect Size (Hedges' g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobias | 5 | 206 | -0.08 | [19] |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 6 | 245 | 0.06 | [19] |

| PTSD | 6 | 239 | 0.02 | [19] |

Note: Effect sizes near zero indicate no significant difference between VRET and the active comparator, establishing non-inferiority.

The data in Table 1 demonstrates that VRET has a large and significant effect in reducing symptoms compared to waitlist or placebo conditions across all listed anxiety disorders [19]. Table 2 confirms that for specific phobias, social anxiety disorder (SAD), and PTSD, VRET is statistically as effective as traditional in vivo exposure therapy, the established gold-standard treatment [19]. This non-inferiority is a cornerstone for the adoption of VRET, particularly for situations where in vivo exposure is impractical, difficult to control, or too costly.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

This protocol is adapted from clinical trials investigating pure VRET without concurrent cognitive interventions [20].

- Objective: To reduce fear of negative evaluation and avoidance of social situations.

- Duration: Typically 8-12 weekly sessions, each lasting 60 minutes.

- Core Components:

- Psychoeducation and Rationale: Provide patients with the Inhibitory Learning Model, explaining that the goal is to violate their expectancies about social catastrophes and learn new, non-threatening associations with social triggers [20].

- Hierarchy Development: Collaboratively create a list of feared social situations, ranked by subjective units of distress (SUDs). Example hierarchy:

- Low anxiety: Making eye contact with a stranger avatar.

- Medium anxiety: Asking a virtual shop clerk for help.

- High anxiety: Giving a presentation to a virtual audience.

- Very high anxiety: Being interviewed for a job by a panel of avatars.

- Virtual Exposure Sessions:

- The therapist uses a VR system capable of rendering various social environments (e.g., a café, a conference room, a busy street) and populating them with avatars.

- The therapist controls variables in real-time from a separate console, including the number and gender of avatars, their gestures (e.g., nodding, looking bored), and the style/topic of dialogue [20].

- Exposure begins with lower-ranked items and progresses gradually. Each session continues until the patient's anxiety shows a significant decrease within the session (habituation) and, more importantly, until the patient's specific catastrophic expectation (e.g., "If I pause during my speech, everyone will laugh") is violated.

- Homework Assignments: Patients are encouraged to practice the skills and confront similar social situations in real life between VRET sessions to promote generalization of learning.

Protocol for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

This protocol synthesizes elements from proven trauma-focused therapies like Prolonged Exposure.

- Objective: To reduce re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms by processing traumatic memories.

- Duration: 10-16 weekly sessions of 90 minutes.

- Core Components:

- Assessment and Trauma Interview: Identify the index trauma and specific sensory triggers (sights, sounds, smells).

- VR Environment Selection/Creation: Customize a virtual environment to closely match the patient's traumatic event (e.g., a virtual Iraq/Afghanistan landscape for combat veterans, a virtual city street for assault survivors) [21].

- Gradual Imaginal and VR Exposure:

- Patients first engage in imaginal exposure, recounting the trauma memory in the safe therapeutic context.

- This is supplemented with VR exposure, where the patient is immersed in the trauma-relevant environment. The therapist gradually introduces trauma-related stimuli (e.g., helicopter sounds, distant shouts, dimmed lighting to simulate night) based on the patient's hierarchy.

- The therapist's role is to guide the narrative and ensure the patient emotionally engages with the memory and the virtual environment without resorting to avoidance strategies [21].

- Processing and Reclaiming Safety: After each exposure, the therapist helps the patient process the experience, focusing on the discrepancy between the memory of the trauma (danger) and the current reality of being safe in the therapist's office.

Theoretical Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The efficacy of VRET is best understood through contemporary psychological models and the neurobiology of fear and anxiety. The following diagram illustrates the core therapeutic workflow and the underlying neural mechanisms it targets.

Diagram 1: VRET Therapeutic Workflow and Neurobiological Basis

This workflow is supported by distinct neurobiological pathways. Fear-dominant disorders (specific phobia, agoraphobia) primarily involve the amygdala-centered fear network [18]. VRET facilitates extinction learning by violating threat expectancies, leading to the formation of new safety memories mediated by the prefrontal cortex inhibiting amygdala activity. For anxiety-dominant disorders like GAD, which involves chronic worry regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the role of exposure is less defined, explaining the emerging but less robust evidence base [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing VRET trials, the following tools and measures are essential.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for VRET Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in Research | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stand-Alone VR Headset | Provides immersive stimulus delivery. Enables controlled, repeatable exposures. | Oculus Quest series (Meta). Modern stand-alone units eliminate the need for a tethered computer, enhancing clinical flexibility [19]. |

| Clinical VR Software Platforms | Provides the therapeutic environments and stimuli specific to different disorders. | Customizable platforms for PTSD (e.g., combat zones), SAD (e.g., virtual audience, job interview), and specific phobias (e.g., heights, flying) [20] [22]. |

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) | Primary outcome measure for SAD trials. Assesses fear and avoidance across social situations. | A gold-standard, clinician-administered scale [23]. |

| Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) | Self-report outcome measure for SAD. Captures fear of negative evaluation, physical symptoms, and fear of uncertainty [23]. | Useful for screening and tracking symptoms. |

| PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) | Standardized self-report measure for assessing PTSD symptom severity. | Critical for establishing baseline and post-treatment efficacy in PTSD trials [21]. |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) | Clinician-rated scale to measure overall anxiety severity. | Used in trials for GAD and other anxiety disorders to assess general anxiety symptoms [24]. |

| Therapist Control Console | Software interface allowing the therapist to control stimuli in the VR environment in real-time. | Essential for tailoring exposure intensity by adjusting variables like avatar behavior, sound effects, and environmental conditions during a session [20]. |

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of anxiety disorders, offering distinct advantages over traditional therapeutic methods. By leveraging immersive technology, VRET enables clinicians to deliver controlled, safe, and accessible exposure therapy that would be impractical or impossible to implement in real-world settings. This application note details the mechanisms, protocols, and empirical support for VRET, providing researchers and clinical professionals with comprehensive frameworks for implementation and study. Evidence from recent randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses confirms that VRET produces outcomes comparable to in-vivo exposure while overcoming critical limitations of traditional approaches through precise stimulus control, enhanced safety parameters, and reduced treatment barriers.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) has emerged as an innovative evidence-based intervention that effectively addresses core limitations of traditional exposure therapy for anxiety disorders. By creating immersive, computer-generated environments, VRET enables precise control over therapeutic stimuli while maintaining a physically safe and psychologically contained setting. The technological foundation of VRET allows for the systematic presentation of fear-eliciting stimuli that can be meticulously calibrated to match individual patient needs and tolerance levels [25]. This controlled approach facilitates the extinction learning process central to exposure therapy while minimizing the risks of premature termination, uncontrolled real-world exposure, and the practical limitations of accessing specific fear contexts.

The efficacy of VRET stems from its ability to create a powerful sense of presence—the subjective experience of "being there" in the virtual environment—while maintaining the clinical safety of the therapist's office. Neurophysiological and behavioral research indicates that individuals respond to virtual environments with anxiety reactions and coping responses similar to those evoked by real-world situations, enabling effective emotional processing and fear extinction [26]. This combination of psychological engagement within a physically safe context represents a fundamental advancement over traditional exposure methods, particularly for trauma-related disorders and specific phobias where real-world exposure may be dangerous, impractical, or ethically complicated.

Comparative Efficacy Data

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy of VRET Across Anxiety Disorders

| Disorder | Comparison Condition | Key Efficacy Metrics | Effect Size/Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobias | In-vivo Exposure | Symptom reduction post-treatment | Comparable effectiveness, high satisfaction rates | [27] |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | Non-VR Treatments | Reduction in anxiety symptoms | Comparable efficacy | [27] |

| PTSD | Traditional Treatments | Symptom reduction | 66%-90% success rates | [28] |

| Public Speaking Anxiety | Waitlist/Control | Reduction in state anxiety | Significant improvement after single session | [29] |

| Performance Anxiety | Yoga Interventions | STAI-Y1/Y2 reduction | Rapid symptom reduction | [30] |

Table 2: Advantages of VRET Versus Traditional Exposure Therapy

| Parameter | Traditional Exposure Therapy | Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Control | Limited, environment-dependent | Precise, gradable, repeatable | Enhanced treatment fidelity |

| Safety Profile | Variable, potential real risk | High, physical safety assured | Reduced liability, ethical advantage |

| Accessibility | Geographic, temporal constraints | Flexible, potential for remote delivery | Increased treatment access |

| Standardization | Challenging across patients | Highly standardized | Improved research validity |

| Dropout Rates | Higher due to discomfort | Lower, enhanced engagement | Improved treatment completion |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Variable, often high | Increasingly affordable | Improved resource allocation |

Core Mechanisms of Action

The Controlled Exposure Paradigm

The fundamental advantage of VRET lies in its capacity for precise stimulus control within an immersive environment. Unlike traditional exposure therapy, which often relies on imagination or difficult-to-manage real-world scenarios, VRET enables clinicians to systematically manipulate multiple sensory dimensions of the exposure experience. This includes visual complexity, auditory stimuli, and even tactile elements through haptic feedback devices [26]. The therapeutic environment can be repeatedly presented with exact consistency, paused for cognitive restructuring, or immediately adjusted in response to patient distress—capabilities largely absent from traditional exposure methods.

This controlled exposure paradigm operates through several distinct mechanisms:

- Stimulus Fidelity: Modern VR systems create highly realistic environments that successfully trigger authentic fear responses while maintaining the patient's awareness of being in a safe therapeutic setting [25].

- Hierarchical Precision: Therapists can construct exposure hierarchies with fine-grained progression steps, systematically increasing stimulus intensity according to individual tolerance levels [28].

- Multi-sensory Engagement: By engaging visual, auditory, and sometimes tactile modalities, VRET facilitates more robust emotional processing than imaginal exposure alone [25].

Safety and Containment Framework

The safety advantages of VRET extend beyond physical protection to include psychological containment mechanisms that facilitate emotional processing. Patients can confront traumatic memories or phobic stimuli with the conscious awareness that the environment is computer-generated and can be terminated immediately if necessary. This safety framework enhances patient willingness to engage with challenging material and reduces treatment refusal and dropout rates [28]. For patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this contained environment enables gradual processing of traumatic memories without the overwhelming intensity that can occur with traditional imaginal exposure.

Diagram 1: VRET Therapeutic Protocol Workflow - This diagram illustrates the controlled, iterative process of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy, highlighting the continuous monitoring and adjustment capabilities.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol for Public Speaking Anxiety

Background: Public speaking anxiety represents a prevalent form of social anxiety that responds robustly to VRET interventions. The following protocol adapts methodology from a multisite experimental study investigating positive affect moderators in VRET for public speaking anxiety [29].

Equipment and Software:

- Fully immersive VR headset with minimum 90Hz refresh rate

- Public speaking virtual environment (auditorium, conference room, or classroom)

- Biofeedback monitoring capability (heart rate, galvanic skin response)

- Standardized assessment tools (STAI-S, self-reported valence scales)

Procedure:

- Pre-assessment: Administer trait positive affect measures, optimism scales, hopefulness inventories, and self-efficacy questionnaires at baseline.

- Psychoeducation: Explain the rationale for exposure therapy, the concept of inhibitory learning, and the VRET process.

- Affect Induction: Implement positive affect induction procedures before exposure sessions when investigating emotional moderators.

- Exposure Sessions:

- Begin with a virtual audience of 5-10 neutral avatars

- Gradually increase audience size and reactivity based on patient distress metrics

- Incorporate performance elements (prepared speech, impromptu speaking)

- Utilize heart rate biofeedback to guide exposure intensity

- Within-session Processing: Conduct cognitive restructuring during session breaks based on performance feedback.

- Post-session Assessment: Measure public speaking anxiety, social phobia symptoms, and self-reported emotional valence.

- Generalization Planning: Develop real-world exposure homework assignments based on VRET progress.

Session Parameters: Single-session protocols typically run 60-90 minutes, while multi-session interventions may involve 3-8 sessions spaced weekly [29].

Protocol for PTSD and Trauma-Related Disorders

Background: VRET enables controlled engagement with trauma memories in cases where in-vivo exposure is impractical or unsafe. This protocol is particularly relevant for combat-related PTSD, accident trauma, and assault survivors.

Equipment and Software:

- High-fidelity VR system with wide field of view

- Trauma-relevant virtual environments (customizable settings)

- Olfactory and tactile feedback components (when available)

- Physiological monitoring integrated with VR software

Procedure:

- Trauma Assessment: Detailed functional analysis of trauma triggers, avoidance patterns, and symptom profile.

- Safe Space Development: Create a personalized virtual "safe space" for patient use during distress management.

- Gradual Exposure Hierarchy:

- Develop multi-sensory hierarchy from least to most triggering elements

- Begin with neutral environmental elements without trauma cues

- Gradually introduce trauma-relevant stimuli across sensory modalities

- Trauma Narrative Integration:

- Combine imaginal reliving with virtual environment exposure

- Incorporate olfactory cues (smoke, gasoline) when relevant to trauma memory

- Use tactile feedback to simulate environment-specific sensations

- Emotional Processing:

- Encourage emotional engagement while practicing coping strategies

- Alternate between trauma focus and present-centered awareness

- Utilize physiological data to guide exposure intensity

- Consolidation Sessions: Schedule periodic booster sessions to maintain treatment gains and address new triggers.

Safety Considerations: Establish clear emotional distress protocols, including immediate exit strategies from the virtual environment and enhanced grounding techniques for dissociation management [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for VRET Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | HTC Vive Pro, Oculus Rift S, Varjo VR-3 | Delivery of immersive environments | Selection depends on visual fidelity requirements, tracking precision, and refresh rate needs |

| Biofeedback Integration | BioPac MP160, Empatica E4, HeartMath Inner Balance | Psychophysiological monitoring | Enables real-time adaptation of virtual environments based on physiological arousal |

| Virtual Environment Software | Bravemind, Psious, Limbix, Oxford VR | Pre-built therapeutic environments | Platform selection determined by target population and customization requirements |

| Assessment Batteries | STAI, CAPS-5, SUDS, PANAS | Standardized outcome measurement | Critical for establishing treatment efficacy and comparing across studies |

| Data Analytics Platforms | Unity Analytics, Custom MATLAB Scripts | Usage pattern analysis and efficacy tracking | Enables examination of dose-response relationships and mechanism of action |

| Stimulus Presentation Tools | WorldViz Vizard, Unity 3D, Unreal Engine | Custom environment development | Required for creating disorder-specific scenarios not available commercially |

Technological Implementation and Workflow

Diagram 2: VRET System Integration and Data Flow - This diagram illustrates the technological ecosystem of VRET, highlighting the integration of patient monitoring, real-time data analysis, and therapeutic intervention.

The technological implementation of VRET requires seamless integration of hardware, software, and therapeutic protocols to achieve the documented advantages over traditional methods. Current systems leverage fully immersive VR technology with integrated biofeedback capabilities that enable real-time adaptation of therapeutic content based on psychophysiological metrics [31]. This closed-loop system represents a significant advancement beyond static exposure protocols, allowing for precision mental healthcare tailored to individual response patterns.

The workflow incorporates continuous data collection throughout the therapeutic process, including:

- Behavioral Metrics: Movement patterns, avoidance behaviors, and interaction data within the virtual environment

- Physiological Measures: Heart rate, heart rate variability, galvanic skin response, and respiratory rate

- Subjective Reports: Periodic subjective units of distress (SUDS) ratings and cognitive appraisal assessments

- Performance Data: Task completion metrics, response times, and engagement levels

This multi-dimensional data ecosystem enables researchers to examine mechanisms of change and treatment responders, ultimately refining VRET protocols for enhanced efficacy [25].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The rapidly evolving landscape of VRET presents numerous research opportunities and clinical innovations. Emerging areas include:

- AI-Enhanced Personalization: Integration of machine learning algorithms to dynamically adjust virtual environments based on real-time patient response patterns [25]

- Remote Treatment Delivery: Development of secure, home-based VRET protocols to increase accessibility while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [31]

- Biomarker Integration: Investigation of neurophysiological and psychophysiological biomarkers to predict treatment response and optimize protocol selection [29]

- Multi-sensory Enhancement: Incorporation of olfactory, vestibular, and haptic feedback to increase ecological validity and treatment generalization [26]

- Preventive Applications: Exploration of VRET as a preventive intervention for at-risk populations before anxiety disorders become fully manifest

The projected growth of the virtual reality therapy market from $1.8 billion in 2023 to approximately $13.9 billion by 2032 reflects both commercial interest and expanding clinical validation [31]. This investment trajectory underscores the importance of continued rigorous research to establish optimal implementation protocols, identify mechanisms of change, and ensure equitable access to these innovative therapeutic tools.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy represents a significant advancement in the treatment of anxiety disorders, offering demonstrable advantages over traditional methods through enhanced control, safety, and accessibility. The protocols and application notes detailed herein provide researchers and clinicians with evidence-based frameworks for implementation and further investigation. As the technology continues to evolve and research expands, VRET holds promise for transforming mental healthcare delivery through personalized, precisely controlled therapeutic experiences that effectively target the core mechanisms maintaining anxiety disorders while overcoming traditional treatment barriers.

Implementing VRET in Clinical and Research Settings: Protocols, Personalization, and Workflow

Application Notes: Core Principles and Rationale

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) is an evidence-based treatment that integrates virtual reality technology within a cognitive-behavioral framework to treat anxiety disorders. Its efficacy is rooted in emotional processing theory, which posits that successful treatment requires the activation and subsequent modification of pathological fear structures in memory [16]. VRET facilitates this by providing controlled, immersive environments where patients can confront feared stimuli without real-world danger, enabling corrective learning and a reduction in avoidance behaviors [16] [3].

A significant advantage of VRET is its capacity to overcome practical and logistical barriers associated with traditional in vivo exposure. It allows for the precise control of sensory stimulation, the creation of otherwise impractical or costly scenarios (e.g., a cross-country flight or a specific traumatic context), and ensures patient confidentiality during sessions [16]. Furthermore, VRET may be more acceptable to patients than traditional exposure, as indicated by lower refusal rates for VR (3%) compared to in vivo exposure (27%) in one study of specific phobias [16]. For clinicians, modern wireless VR systems with controller-free hand tracking have been shown to improve attitudes toward VRET after direct experience, highlighting the importance of usability and immersion for clinical adoption [32].

Standardized VRET Protocol for Anxiety Disorders

The following protocol outlines a standardized course of treatment, adaptable for various anxiety disorders, from specific phobias to social anxiety disorder.

Phase I: Initial Psychoeducation and Treatment Rationale (Sessions 1-2)

Objective: To establish therapeutic rapport, provide a comprehensive understanding of the anxiety disorder, and introduce the rationale for VRET.

Methods:

- Assessment: Conduct a detailed clinical interview and use standardized measures (e.g., Acrophobia Questionnaire [AQ], Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale [LSAS], Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7]) to establish a baseline and identify specific fear structures [33] [3].

- Psychoeducation: Educate the patient on the nature of their anxiety disorder using the cognitive-behavioral model. Explain the roles of avoidance, anticipatory anxiety, and the fear maintenance cycle.

- VRET Rationale: Explain the principles of exposure therapy and how VR creates a safe, controlled environment for confronting fears. Emphasize that the virtual environment is designed to feel realistic and elicit anxiety to provide opportunities for new learning. Normalize the experience of discomfort as a sign that the treatment is activating the fear network [16] [32].

- Introduction to Technology: Familiarize the patient with the VR hardware (head-mounted display, controllers, or hand-tracking). Allow them to explore a neutral virtual environment to reduce tech-related anxiety and address any concerns about simulator sickness [34] [32].

Phase II: Collaborative Hierarchy Development (Session 2)

Objective: To create a personalized and graded exposure hierarchy.

Methods:

- Stimulus Identification: Collaboratively with the patient, identify all stimuli, situations, and contextual factors related to their fear. For a fear of heights, this might include looking out a second-story window, standing on a ladder, or walking over a glass floor on a skyscraper [16] [32].

- SUDs Rating: Have the patient rate each identified situation on a Subjective Units of Distress (SUDs) scale from 0 (no anxiety) to 100 (maximum anxiety) [32].

- Hierarchy Construction: Order the situations from least (e.g., SUDs 20-30) to most anxiety-provoking (e.g., SUDs 90-100). This creates a roadmap for treatment, ensuring early success and promoting self-efficacy.

Table 1: Sample Exposure Hierarchy for Acrophobia

| Hierarchy Step | Virtual Scenario Description | Target SUDs (0-100) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Standing on a solid, wide platform, 2 meters high, with high railings. | 20-30 |

| 2 | Looking down from a 5-meter high interior balcony. | 40-50 |

| 3 | Walking across a narrow wooden plank, 5 meters high. | 50-60 |

| 4 | Riding a glass elevator up the outside of a tall building. | 60-70 |

| 5 | Standing on a transparent glass floor, 50 meters high. | 70-80 |

| 6 | Performing a task (e.g., retrieving an object) on a high, exposed platform with wind effects. | 80-90 |

| 7 | Being rescued from a gondola on a broken ski-lift over a cliff. | 90-100 |

Phase III: Graded Virtual Reality Exposure (Sessions 3-12+)

Objective: To systematically expose the patient to feared stimuli in virtual reality, progressing through the hierarchy to achieve habituation and inhibitory learning.

Methods:

- Session Structure: Each session begins with a brief check-in and setting an agenda. The majority of the session (approximately 30-45 minutes) is dedicated to VR exposure.

- Exposure Conduct: The patient enters the VR scenario corresponding to their current position on the hierarchy. The therapist's role is to guide, encourage, and ensure the patient remains in the situation until their anxiety begins to decrease.

- Within- and Between-Session Progress: A step is considered mastered when the patient's SUDs rating decreases significantly (e.g., by 50% or more) during a single exposure (within-session habituation) and when they report lower initial SUDs upon re-encountering the same scenario in a subsequent session (between-session habituation). Progression to the next hierarchy step is collaborative [16].

- Individualization: The therapist should use clinical judgment to tailor the exposure. This may include repeating scenes, adjusting virtual parameters (e.g., adding turbulence to a virtual flight), or focusing on specific stimuli based on the patient's fear structure [16].

- Processing: After each exposure, briefly process the experience. Discuss what the patient learned, whether their feared outcomes occurred, and how they coped, reinforcing the violation of negative expectancies [3].

Mechanisms of Change and Neural Correlates

Therapeutic change in VRET is driven by mechanisms such as expectancy violation (experiencing that a feared outcome does not occur), habituation (reduction in fear response over time), and enhanced self-efficacy (increased confidence in one's ability to cope) [3]. Neuroimaging studies provide preliminary evidence of the neural underpinnings of these changes. A 2025 fMRI study on acrophobia found that VRET led to decreased activity in the default mode network (e.g., precuneus, middle temporal gyrus) and the primary visual cortex (calcarine), regions associated with self-referential thinking and visual processing of threat. This suggests VRET may work by modulating the brain networks responsible for processing fear and contextualizing threatening stimuli [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for VRET Research

| Item | Function in Research | Exemplars / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platform | Provides the immersive sensory experience. Key features include display resolution, field of view, tracking capabilities, and comfort. | Modern, commercially available standalone headsets (e.g., Meta Quest系列) are recommended for their wireless freedom, controller-free hand tracking, and high resolution, which enhance immersion and reduce simulator sickness [32]. |

| Disorder-Specific VR Software | Contains the virtual environments and scenarios designed to elicit specific fears. | Commercially available or custom-built applications for disorders like acrophobia (e.g., scenarios involving cliffs, bridges), social anxiety (e.g., virtual auditorium for public speaking), and PTSD [16] [32] [3]. |

| Clinical Assessment Batteries | Quantifies symptom severity, treatment efficacy, and mechanism of change. | Primary: Disorder-specific measures (e.g., Acrophobia Questionnaire [AQ], Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale [LSAS]). Secondary: General anxiety (GAD-7), behavioral avoidance tests (BAT), and subjective units of distress (SUDs) [33] [3]. |

| Psychophysiological Recording Equipment | Provides objective, non-verbal indices of arousal and fear activation during exposure. | Equipment to measure heart rate variability (HRV), galvanic skin response (GSR), and electroencephalography (EEG) can be synchronized with VR events to capture real-time physiological responses [16]. |

| Data Integration & Analysis Software | Manages and analyzes multi-modal data (subjective, behavioral, physiological). | Platforms like VRNetzer, which allow for interactive data visualization, or statistical software (R, Python) for analyzing clinical and experimental data [35]. |

Experimental Workflow for a VRET Session

The following diagram illustrates the standardized, iterative workflow for conducting a single VRET exposure session, from preparation to progression planning.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of anxiety disorders, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to enable precise alignment with individual fear structures. Fear structures—comprising stimulus representations, response representations, and meaning-based interpretations—form the core pathological framework of anxiety disorders [3]. The plasticity of virtual environments offers unprecedented opportunities to deconstruct and target these elements with customized therapeutic experiences. This protocol details the methodology for individualizing VR exposure by identifying key fear components and engineering virtual scenarios that directly match these individualized profiles.

Research demonstrates that individualized VRET produces outcomes comparable to traditional in-vivo exposure while overcoming significant accessibility barriers [7] [36]. For anxiety disorders, including social anxiety disorder (SAD) and specific phobias, effective treatment requires activating the specific fear network while providing opportunities for corrective learning through expectancy violation and inhibitory learning [3]. The controlled nature of virtual environments enables therapists to systematically manipulate scenario parameters to achieve this precise activation while maintaining patient safety and therapeutic alliance.

Theoretical Foundations

Fear Structure Model in Anxiety Disorders

The efficacy of exposure therapy hinges on directly accessing and modifying pathological fear structures. According to emotional processing theory, these structures contain information about feared stimuli, fear responses, and their associated meanings [3]. In social anxiety, for instance, core fears often revolve around rejection, appearing foolish, or being the center of attention [3]. These fears manifest in avoidance behaviors that prevent disconfirmatory experiences. Virtual environments can be engineered to contain elements that specifically trigger an individual's unique fear structure while ensuring the presence of sufficient safety cues to encourage engagement.

Mechanisms of Change in Virtual Reality Exposure

VRET facilitates fear reduction through multiple established mechanisms:

- Expectancy violation: Creating mismatches between predicted and actual outcomes

- Within- and between-session habituation: Reduction of fear response through repeated exposure

- Self-efficacy enhancement: Building confidence through successful virtual experiences [3]

The inhibitory learning model posits that successful exposure creates new, non-threat associations that compete with existing fear associations [3]. VR environments optimally support this process by allowing precise control over exposure parameters to maximize expectancy violation while managing anxiety levels. For adolescents with social anxiety, the game-like features of VR may increase treatment adherence and motivation compared to traditional exposure [3].

Assessment and Fear Structure Mapping

Comprehensive assessment forms the foundation for individualizing virtual environments. The following multi-method approach ensures precise mapping of individual fear structures:

Clinical Interview and Standardized Measures

Table 1: Core Assessment Domains and Instruments

| Assessment Domain | Specific Instruments | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Symptom Severity | SPAI-18, LSAS-avoidance [3] | Quantifies avoidance and anxiety intensity |

| Core Fear Identification | Fear Hierarchy Questionnaire, Clinical Interview [3] | Identifies specific feared outcomes and triggers |

| Functional Impairment | SPWSS, Psychosocial Functioning scales [3] | Assesses impact on daily life domains |

| Cognitive Mechanisms | Expectancy of Threat Scale [3] | Measures probability and cost estimates of feared outcomes |

Behavioral Avoidance Assessment

Virtual behavioral approach tests (V-BAT) provide objective measures of avoidance patterns. During V-BAT, patients navigate virtual environments while researchers record:

- Approach distance to feared stimuli

- Physiological correlates (heart rate, skin conductance)

- Self-reported distress levels at each proximity

- Avoidance behaviors and safety signals utilized

This data directly informs the initial exposure gradient and identifies specific environmental elements that trigger maximal fear activation.

Individual Difference Moderators

Assessment should identify potential moderators of VRET response, including:

- Clinical variables: Comorbidity, pre-intervention severity [3]

- Personality traits: Behavioral inhibition/activation, openness to experience [3]

- VR-related factors: Technological affinity, presence susceptibility [3]

- Demographic factors: Age, gender, prior treatment history

Virtual Environment Tailoring Protocols

Parameter Customization Framework

Virtual environments can be systematically tailored across multiple dimensions to match individual fear structures:

Table 2: Virtual Environment Customization Parameters

| Parameter Domain | Customization Options | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Social Environment | Audience size, composition, responsiveness [3] | Social anxiety hierarchy implementation |

| Performance Context | Formality, evaluation criteria, consequence significance [3] | Public speaking anxiety individualization |

| Sensory Elements | Visual fidelity, auditory stimuli, haptic feedback [17] | Gradual intensity modulation |

| Interactive Capacity | Agent responsiveness, user control level, consequence realism [11] | Self-efficacy enhancement through mastery experiences |

| Temporal Factors | Exposure duration, scenario progression pace [36] | Within- and between-session habituation planning |

Stimulus Calibration Protocol

The following workflow details the procedure for calibrating virtual stimuli to individual fear structures:

Social Anxiety Individualization Protocol

For social anxiety disorder, environment tailoring follows this specific pathway:

Implementation guidelines for social anxiety VRET:

- Performance anxiety: Begin with small, non-reactive virtual audiences and gradually increase audience size and responsiveness based on patient tolerance [3]

- Interaction anxiety: Program virtual humans with varying levels of social demand, starting with scripted interactions and progressing to more dynamic conversations

- Observation anxiety: Create environments where the patient is the focus of attention without performance demands

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VRET Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware | Meta Quest 2/3, HTC Vive, Valve Index [17] [6] | Balanced mobility and graphical capability for clinical research |

| Therapeutic Software | Doxy.me VR, PsyTechVR [17] [6] | Pre-programmed, evidence-based virtual environments with customization capacity |

| Physiological Monitoring | Heart rate sensors, GSR devices, respiration monitors [17] | Objective fear activation measurement during exposure |

| Assessment Platforms | REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [6] | Automated collection of self-report and clinical outcome data |

| Presence Measures | Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ), Slater-Usoh-Steed Questionnaire | Quantification of immersion and reality perception in virtual environments |

Technical specifications for optimal VRET research implementation:

- Computer systems: Minimum NVIDIA RTX 3060 graphics, Intel i5/Ryzen 5 processor, 16GB RAM [17]

- Tracking systems: Six degrees of freedom (6DoF) controllers with inside-out tracking

- Sensory add-ons: Stereo headphones, optional haptic feedback devices [17]

- Therapist interface: Dedicated control dashboard for real-time parameter adjustment [17]

Experimental Protocol for VRET Efficacy Trials

Study Design and Participant Recruitment

This protocol outlines a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing individualized VRET to standard in-vivo exposure:

Participant selection:

- Target sample: 120 participants (ages 12-16 for adolescent focus; 18+ for adult studies) with subclinical to moderate social anxiety or specific phobia [3]

- Diagnostic criteria: DSM-5/ICD-10 criteria confirmed via structured clinical interview

- Exclusion criteria: Comorbid psychotic disorders, active substance dependence, seizure disorders, visual impairments uncorrectable in VR

Randomization procedure:

- 1:1 allocation to VRET or in-vivo exposure using computer-generated randomization sequences

- Stratification by anxiety severity, phobia subtype, and prior treatment history

Intervention Protocol

Both active conditions receive a seven-session exposure-based intervention with the following structure:

Table 4: Session-by-Session VRET Protocol

| Session | Primary Focus | VR Customization Elements | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Psychoeducation & fear hierarchy building | Environment familiarization without exposure elements | 45-60 minutes |

| 3-5 | Graduated exposure | Systematic parameter adjustment based on fear activation | 45-60 minutes |

| 6 | Consolidation & cognitive restructuring | Maximum fear trigger exposure with cognitive challenges | 45-60 minutes |

| 7 | Relapse prevention & generalization | Novel scenario application of learned skills | 45-60 minutes |

For specific phobias, evidence supports efficacy with single, extended sessions (45-180 minutes), while social anxiety and agoraphobia typically require 8-12 sessions [36].

Individualization Procedures

The experimental protocol incorporates these key individualization steps:

- Pre-treatment assessment analysis to identify individual fear structure components

- Baseline VR environment calibration using test exposures with physiological monitoring

- Session-by-session parameter adjustment based on within- and between-session habituation patterns

- Dynamic difficulty adjustment during sessions based on real-time distress metrics

Outcome Measures and Data Collection

Primary and secondary outcomes assessed at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-/6-month follow-ups:

Primary outcomes:

- Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI-18)

- Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale - avoidance subscale (LSAS-avoidance) [3]

Secondary outcomes:

- Social Phobia Weekly Summary Scale (SPWSS)

- General well-being indicators (resilience, depression, psychosocial functioning) [3]

Process measures:

- Expectancy violation scales

- Self-efficacy ratings

- Working alliance inventories

- Presence and immersion questionnaires

Data Analysis Plan

Statistical approaches for evaluating individualized VRET efficacy:

Primary efficacy analysis:

- Linear mixed models (LMM) to examine condition × time interactions on primary outcomes

- Intent-to-treat analysis with multiple imputation for missing data

Mechanism analysis:

- Parallel process latent growth curve modeling to test mediators (expectancy violation, self-efficacy)

- Moderation analysis to identify patient characteristics predicting optimal VRET response

Individualized effects analysis:

- Person-centered approaches (e.g., latent class growth analysis) to identify differential response trajectories

- Dose-response relationships between customization precision and outcomes

Sample size justification: 120 participants provide 80% power to detect medium effects (f = 0.25) in 3 × 4 mixed ANOVA with alpha = 0.05.

Ethical and Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of individualized VRET requires attention to:

- Therapeutic alliance: Maintain strong rapport despite technology mediation through pre-exposure preparation and post-exposure processing [11]

- Safety protocols: Monitor cybersickness symptoms and provide abort scenarios for overwhelming anxiety

- Equipment sterilization: Implement hygienic protocols for shared head-mounted displays

- Technical competence: Ensure research staff proficiency in both clinical procedures and VR operation

- Data security: Protect patient data in compliance with HIPAA and other relevant regulations [6]

This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for individualizing virtual environments in exposure therapy research. By systematically tailoring VR scenarios to match individual fear structures, researchers can maximize the efficacy and precision of VRET for anxiety disorders. The detailed methodologies, assessment approaches, and customization parameters outlined here enable rigorous investigation of how personalized virtual reality interventions can optimize therapeutic outcomes across different anxiety presentations.

Future research directions should include examining the additive benefits of physiological monitoring to guide real-time personalization, developing algorithms for automated environment adjustment, and investigating how individual difference factors moderate response to specific VR environment parameters.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of anxiety disorders, leveraging immersive technology to create controlled, safe, and customizable therapeutic environments. Framed within a broader thesis on VRET for anxiety disorders, this document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three core clinical indications: specific phobias, social anxiety disorder (SAD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The efficacy of VRET is grounded in its capacity to facilitate inhibitory learning and emotional processing by systematically exposing patients to fear-eliciting stimuli without the real-world risks, thereby promoting corrective experiences and fear extinction [22] [11]. The following sections synthesize current evidence, quantify treatment effects, and delineate step-by-step protocols for researchers and clinical scientists.

The quantitative efficacy of VRET across anxiety disorders is established by multiple meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The data below summarize key outcome measures for the disorders of interest.

Table 1: Meta-Analysis Findings for VRET Efficacy

| Disorder Category | Number of Studies & Participants | Pooled Effect Size (SMD/Hedges' g) | Comparison Condition | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders (Broad) | 33 studies (n=3,182) | SMD = -0.95 [95% CI: -1.22, -0.69] | Conventional Interventions (CBT, TAU) | [37] |