Virtual Reality in Behavioral Neuroscience: Advancing Research, Therapy, and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative integration of Virtual Reality (VR) in behavioral neuroscience, addressing a core audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Virtual Reality in Behavioral Neuroscience: Advancing Research, Therapy, and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of Virtual Reality (VR) in behavioral neuroscience, addressing a core audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles establishing VR as a tool for studying neuroplasticity and context-dependent behaviors. The scope extends to methodological innovations across human and preclinical research, including novel protocols for psychosis, ADHD, and motor rehabilitation. The review critically examines troubleshooting for technical and ethical challenges in implementation and provides a comparative analysis of VR's efficacy against conventional therapies. Finally, it validates VR's role through empirical evidence and discusses its emerging function in accelerating therapeutic discovery via platforms like eBrain for in silico drug testing.

The Neuroscience of Presence: How VR Creates Controlled, Ecologically Valid Environments for Research

Leveraging Immersion and Presence to Elicit Naturalistic Brain and Behavioral Responses

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in behavioral neuroscience, creating a critical middle ground between rigorous experimental control and essential ecological validity [1]. Unlike traditional laboratory paradigms that often rely on repetitive, passive sensory stimulation, VR establishes a closed-loop system where a participant's actions directly shape their sensory experience [1]. This interaction fosters immersion, an objective property of the technology, and presence, the subjective psychological sense of "being there" in the virtual environment [2]. The core premise of this application note is that by strategically designing VR to maximize presence, researchers can elicit more naturalistic brain and behavioral responses, thereby enhancing the translational value of preclinical and clinical research, including drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Factors

The efficacy of VR in eliciting naturalistic responses hinges on the relationship between immersion and presence. Immersion is determined by the technology's ability to provide rich, multisensory stimuli and seamless interactivity, while presence is the user's psychological response to that immersion [2]. Key factors influencing this relationship include:

- Vibrancy and Fidelity: The breadth (number of senses engaged) and depth (quality and realism) of sensory information. Higher fidelity, which includes detailed 3D objects and realistic object behavior, strengthens the immersive illusion [2].

- Interactivity and User Control: The system's responsiveness (speed), the range of possible interactions (range), and the naturalness of the mapping between user actions and environmental changes (e.g., head tracking) are crucial for a sense of agency and presence [2].

- Embodied Simulation: Neuroscience suggests that VR is effective because it shares the brain's fundamental mechanism for regulating the body in the world: embodied simulation. VR maintains a model of the body and space, predicting the sensory consequences of movement, much like the brain does, allowing for targeted alteration of bodily experience and cognitive change [3].

Quantitative Data on Presence and Cybersickness

The following tables summarize empirical data on how different VR environmental factors influence key user experiences, including presence and cybersickness, which are critical for designing valid experiments.

Table 1: Impact of Static vs. Dynamic VR Environments on User Experience (n=30) [4]

| Metric | Static Environment | Dynamic Environment | Significance & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Level | No significant change from baseline (p=0.464) | Significant decrease (p=0.002) | Dynamic environments can induce relaxation. |

| Experienced Relaxation | No significant change (p=0.455) | Significant increase (p<0.001) | Aligns with stress reduction findings. |

| Cybersickness Symptoms | Minor disturbances only | Progressive, significant increase | Dynamic stimuli increase sensory conflict and cognitive load. |

Table 2: WCAG Color Contrast Ratios for Accessible Visual Design [5] [6]

| Element Type | Minimum Ratio (AA Rating) | Enhanced Ratio (AAA Rating) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Body Text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 |

| Large-Scale Text (≥18pt or 14pt bold) | 3:1 | 4.5:1 |

| UI Components & Graphics (icons, graphs) | 3:1 | Not defined |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comparing Spatial Presence and Emotional Response in Static vs. Dynamic Environments

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating how different VR environments influence spatial presence and emotional states [4].

1. Objective: To assess and compare the sense of spatial presence, emotional response, and cybersickness symptoms induced by static and dynamic virtual reality environments.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- VR Headset: Oculus Meta Quest 2 or equivalent, capable of displaying 360° content.

- Software: A platform for displaying 360° videos (e.g., YouTube VR).

- Content: Two 20-minute videos: (A) a static environment (e.g., a tranquil beach panorama); (B) a dynamic environment (e.g., a roller coaster ride).

- Questionnaires:

- Spatial Presence Experience Scale (SPES): To quantify the feeling of presence.

- I-PANAS-SF (International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule): To evaluate emotional states.

- Virtual Reality Sickness Questionnaire (VRSQ): To measure cybersickness symptoms.

- Swivel Chair: To allow participants to rotate and explore the 360° environment freely.

3. Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit healthy adult participants. Obtain informed consent. Record baseline physiological or self-reported measures of stress and relaxation.

- Baseline Assessment: Administer the I-PANAS-SF and VRSQ to establish pre-exposure states.

- VR Exposure:

- Participants experience both the static and dynamic environments in a counterbalanced order to control for sequence effects.

- Each session lasts 20 minutes, with a minimum 20-minute break between sessions to dissipate any potential cybersickness.

- Participants are instructed to sit on the swivel chair and explore the environment naturally.

- Post-Exposure Assessment: Immediately after each VR session, re-administer the SPES, I-PANAS-SF, and VRSQ.

- Data Analysis:

- Use paired t-tests or non-parametric equivalents to compare pre- and post-exposure scores for each environment.

- Compare SPES and VRSQ scores between the static and dynamic conditions using ANOVA or similar statistical models.

Protocol 2: Assessing Memory Confusion Between Virtual and Real Worlds

This protocol is based on a study demonstrating that VR experiences can blur the line with reality, affecting memory and behavior [7].

1. Objective: To determine the extent to which elements and events from a virtual environment are later confused with or transferred to reality.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- VR System: A headset and software capable of creating a highly interactive virtual room.

- Virtual Content: A detailed virtual model of a physical room, including a virtual experimenter avatar and objects like a chair and a tablet.

- Real-World Room: A physical room that corresponds to the virtual model.

3. Procedure:

- Day 1 - VR Session:

- Participants enter the VR environment and interact with a virtual experimenter.

- The avatar instructs participants to sit on a virtual chair. The presence or absence of a corresponding real chair is noted.

- The avatar places a virtual tablet into a virtual drawer. Participants observe this action.

- Day 7 - Real-World Follow-up:

- Participants are brought into the corresponding real-world room.

- Researchers observe if participants spontaneously attempt to sit where the virtual chair was or check for the real chair's presence.

- Participants are asked to find a tablet. Researchers record if they look in the drawer where the virtual tablet was placed.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of participants who (a) sat without checking for the real chair, and (b) used the VR memory to locate the tablet in the real world.

- Use Bayesian analysis to provide robust evidence for the effect size of the confusion.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

VR Immersion-Presence Pathway

Experimental Workflow for VR Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Immersive VR Neuroscience Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) e.g., Meta Quest 2 [4] | Provides the visual and auditory immersive experience. Must have high resolution, refresh rate, and precise head-tracking to maximize immersion and minimize latency-induced cybersickness. |

| VR-Compatible Swivel Chair | Allows participants to physically rotate and explore 360° environments, enhancing realism and spatial presence compared to a fixed seat [4]. |

| Spatial Presence Experience Scale (SPES) | A validated self-report questionnaire to quantitatively measure the subjective feeling of "being there" in the virtual environment, a key dependent variable [4]. |

| Virtual Reality Sickness Questionnaire (VRSQ) | A critical tool for monitoring adverse effects like nausea and dizziness, which can confound behavioral and neural data and act as a covariate in analysis [4]. |

| Biometric Acquisition System (EEG, fNIRS, GSR) | Enables the collection of objective physiological and neural correlates of presence, emotional arousal, and cognitive load, complementing self-report data [1]. |

| Color Contrast Analyzer (e.g., WebAIM's) | Ensures that any text or graphical elements in the VR environment meet WCAG guidelines, guaranteeing legibility for all participants and avoiding confounding based on visual ability [5] [6]. |

| Dynamic vs. Static VR Content | Dynamic content (e.g., roller coasters) is potent for inducing strong emotional and physiological responses, while static content (e.g., beaches) is useful for control conditions or relaxation studies [4]. |

VR as a Tool for Precise Manipulation of Environmental Context and Sensory Stimuli

Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in behavioral neuroscience, enabling researchers to exert unprecedented control over environmental context and sensory stimuli. By generating immersive, computer-generated environments, VR bridges the critical gap between highly controlled laboratory settings and the ecological validity of real-world experiences [8]. This capability allows for the precise presentation and systematic manipulation of complex, dynamic stimuli within realistic contexts, facilitating the rigorous investigation of brain-behavior relationships. The technology is particularly potent for studying processes like spatial navigation, learning, and emotional responses, as it can evoke neural and behavioral responses that parallel those observed in the real world [9] [10]. The following sections provide detailed application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging VR in neuroscience research and drug development.

Quantitative Data on VR Efficacy and Manipulation

Data from recent studies demonstrates the quantitative impact of VR manipulations on behavioral and physiological outcomes. The table below summarizes key findings from research on sensory manipulation and attentional modulation.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of VR Environmental Manipulations on Behavioral and Physiological Outcomes

| Study Focus | Experimental Manipulation | Key Behavioral/Psychophysiological Findings | Implications for Neuroscience Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Perception in Chronic Low Back Pain [11] | Visual-proprioceptive feedback manipulated during lumbar extension:- E- (Understated): VR showed 10% less movement.- E+ (Overstated): VR showed 10% more movement. | - E- condition increased pain-free Range of Motion (ROM) by 20% vs. control (p=0.002) and by 22% vs. E+ (p<0.001).- Patients with higher kinesiophobia and disability showed greater improvement in E-. | VR can directly modulate sensorimotor processing and pain thresholds, useful for testing analgesics and neuropsychiatric drugs. |

| Sustained Attention with Visual Distractors [12] | Performance on a virtual classroom task compared under conditions with and without visual distractors. | - Distractors significantly increased commission errors, omission errors, and multipress responses.- P300 latency significantly prolonged at CPz, Pz, and Oz electrodes.- Sample and fuzzy entropy increased in frontal, central, and parietal regions. | Provides a validated paradigm and EEG biomarkers for probing attention and cognitive control, relevant for ADHD and schizophrenia research. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful VR experimentation requires a suite of hardware and software "reagents." The following table details the core components of a VR research system.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VR Neuroscience

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Common Models | Critical Function in VR Research |

|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | HTC Vive Pro, Oculus Rift S [11] [13] | Provides the immersive visual experience; key variations include display resolution, field of view, and tracking capabilities. |

| Tracking System | Base stations (e.g., HTC Lighthouse), integrated inside-out tracking [13] | Precisely monitors the user's head and limb position in 3D space, enabling naturalistic movement and interaction. |

| Physiological Data Acquisition | EEG systems, Electrocardiogram (ECG), Electrodermal Activity (EDA) sensors [12] [14] | Provides objective, continuous physiological measures of cognitive load, arousal, and emotional state (e.g., P300, heart rate variability). |

| VR Development Platform | Unity, Unreal Engine [8] | Software environment used to design, build, and program the virtual environments and experimental logic. |

| Interaction Controllers | HTC Vive controllers, Oculus Touch [13] | Allows users to interact with and manipulate virtual objects, enriching the sense of presence and enabling complex behavioral tasks. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: VR with Neurofeedback for Auditory Verbal Hallucinations

This protocol, adapted from a current clinical trial, outlines a method for studying and treating symptoms of psychosis [9].

- Objective: To investigate the feasibility and initial efficacy of a hybrid treatment (Hybrid) integrating VR, neurofeedback, and cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp) for modulating auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs).

- Materials:

- VR System: A head-mounted display capable of rendering immersive environments.

- Neurofeedback System: Electroencephalography (EEG) system for real-time measurement of high-β band power.

- Software: Custom VR software that includes an exposure hierarchy and a visual interface for neurofeedback (e.g., a bar graph representing β-power).

- Procedure:

- Participant Screening: Recruit participants with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and experiencing AVHs. Obtain informed consent.

- Baseline Assessment: Conduct clinical interviews and baseline symptom ratings (e.g., using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale).

- VR Environment Creation (Symptom Capture): Collaboratively design a personalized VR environment with the participant that incorporates triggers for their AVHs (e.g., a busy street, a specific room).

- Exposure and Neurofeedback Sessions:

- Participants receive 12 weekly, face-to-face sessions.

- In each session, the participant is immersed in the personalized VR environment, which is calibrated to a specific level on a pre-defined exposure hierarchy.

- Concurrently, EEG is recorded. Participants are instructed to use mental strategies to downregulate the high-β power activity associated with their symptoms, guided by the real-time visual neurofeedback display.

- The clinician provides CBTp throughout the session to support cognitive restructuring and coping strategy development.

- Progression: As participants achieve mastery at one level of the exposure hierarchy (e.g., successful self-regulation of neural target), they progress to a more challenging level in subsequent sessions.

- Post-Intervention Assessment: Repeat clinical ratings and user experience surveys (assessing acceptability, helpfulness, engagement, and safety on a 5-point Likert scale) at the end of the 12 sessions.

- Analysis:

- Primary Outcomes: Feasibility and acceptability, defined by consent rates, session completion rates, and user experience ratings (a pre-set threshold for success is >70% of participants rating 3 or above on the 5-point scale).

- Secondary Outcomes: Change in clinical symptom scores, ability to self-regulate the target EEG band, and progression through the VR exposure hierarchy.

Protocol 2: Manipulating Visual-Proprioceptive Feedback to Modulate Pain

This protocol details a method for investigating the influence of top-down visual processes on pain perception, a key area for analgesic drug development [11].

- Objective: To determine whether manipulating visual-proprioceptive feedback in VR can alter the threshold of movement-evoked pain in individuals with chronic low back pain (LBP).

- Materials:

- VR System: HTC Vive Pro headset with trackers placed on the participant's waist and feet.

- Motion Capture: Electro-goniometer to measure the precise lumbar range of motion (ROM).

- Software: A custom VR application (e.g., a virtual gymnasium) where an avatar's movement and a visual bar's height are linked to the participant's lumbar extension.

- Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit adults with non-specific chronic LBP. Exclude those with specific spinal pathologies.

- Baseline Questionnaires: Administer scales for pain intensity (NRS), kinesiophobia, disability, and catastrophising.

- Calibration: Calibrate the VR system so the participant's actual lumbar extension is accurately mirrored by their avatar and the virtual bar.

- Experimental Task:

- Participants perform lumbar spine extension until the onset of pain under three conditions in a randomized order:

- Control (E): Lumbar extension without VR.

- Understated Feedback (E-): VR visual feedback is manipulated to show 10% less movement than the actual ROM (GainExt = 0.9).

- Overstated Feedback (E+): VR visual feedback is manipulated to show 10% more movement than the actual ROM (GainExt = 1.1).

- For each condition, the task is repeated 3 times, and the pain-onset ROM is recorded by the electro-goniometer.

- Participants perform lumbar spine extension until the onset of pain under three conditions in a randomized order:

- Data Collection: Record the ROM at pain onset for each repetition in each condition.

- Analysis:

- Use Friedman tests to assess within-group differences in ROM across the three conditions (E, E-, E+).

- Conduct post-hoc analyses to compare specific conditions.

- Use regression analyses to determine if baseline levels of kinesiophobia, disability, or catastrophising moderate the effect of the visual manipulation.

Best Practices and Methodological Framework

The integration of VR into rigorous neuroscience and drug development requires adherence to a structured methodological framework. The VR Clinical Outcomes Research Experts (VR-CORE) committee has proposed a phased model to guide this process [15]:

- VR1 Studies (Content Development): This initial phase focuses on treatment development using human-centered design principles. It involves:

- Inspiration through Empathizing: Conducting observations and interviews with patient and provider end-users to understand their needs, struggles, and expectations.

- Ideation through Team Collaboration: Sharing insights within a multidisciplinary team to generate ideas through storyboarding and mind mapping.

- VR2 Studies (Early Testing): These trials assess feasibility, acceptability, tolerability, and initial clinical efficacy. They are typically smaller in scale and may use open-label designs.

- VR3 Studies (Efficacy Trials): These are randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) that compare the VR intervention against an appropriate control condition to evaluate its efficacy on clinically important outcomes.

When combining VR with other physiological measures like EEG, several technical considerations are paramount [12] [8]. The VR system and the physiological recording system must be synchronized to ensure data can be accurately aligned. Furthermore, developers must account for potential electromagnetic interference between the VR hardware and sensitive bio-sensors, which may require specialized shielding or filtering during data processing.

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful tool in behavioral neuroscience for inducing functional neuroplasticity within sensory-motor pathways. This application note synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that VR-based interventions promote cortical reorganization through mechanisms including multisensory integration, error-based learning, and dopaminergic reward pathways. We provide standardized protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers investigating VR-induced neuroplasticity, with particular relevance for developing novel therapeutic interventions in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Quantitative data from recent studies confirm that VR training significantly modulates brain activity patterns, enhances synaptic plasticity markers, and improves functional outcomes across patient populations.

Virtual reality (VR) technology has transitioned from a speculative tool to a validated platform for investigating and inducing neuroplasticity in behavioral neuroscience research. Neuroplasticity—the brain's remarkable capacity to reorganize its structure, function, and connections in response to experience—represents a fundamental mechanism through which VR interventions produce therapeutic effects [16]. The integration of VR in neuroscience facilitates exploration of complex neural processes in controlled, immersive environments that simulate real-world scenarios while allowing precise manipulation of sensory inputs and measurement of corresponding neurological responses [16].

VR environments create a dynamic interface between sensory inputs, motor responses, and cognitive engagements, triggering a cascade of neuroplastic changes that alter synaptic connections, neural circuitry, and functional brain networks [16]. These mechanisms are particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking non-pharmacological adjuvants or evaluating neuroplasticity-enhancing compounds. The translational potential of VR-induced neuroplasticity spans multiple neurological conditions including stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and neuropsychiatric disorders where synaptic reorganization is compromised [16] [17].

Theoretical Framework: Mechanisms of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

Neurobiological Foundations

VR-induced neuroplasticity operates through several interconnected mechanisms that promote structural and functional reorganization of neural circuits:

Multisensory Integration: VR concurrently engages visual, auditory, and proprioceptive systems, creating rich sensory experiences that encourage synaptic reorganization through cross-modal plasticity [17]. This multi-sensory stimulation is particularly effective for facilitating cortical remapping in damaged neural pathways.

Error-Based Learning with Real-Time Feedback: Advanced VR platforms capture real-time kinematic data, enabling immediate feedback and task adjustment that reinforces correct movements while discouraging maladaptive patterns [17]. This closed-loop system mirrors principles of motor learning by strengthening residual pathways through error correction mechanisms.

Reward Mechanisms and Cognitive Engagement: Gamification and immersive scenarios inherent to VR environments stimulate dopaminergic pathways in the ventral striatum, which are crucial for motivation, learning consolidation, and long-term potentiation [17]. The interactive, goal-oriented nature of VR enhances cognitive functions including attention, memory, and executive control while promoting adherence to therapeutic protocols.

Molecular Correlates of VR-Induced Plasticity

At the molecular level, VR experiences trigger cascades that promote synaptic strengthening and neural reorganization:

Neurotrophic Factor Modulation: VR stimulation increases expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports neuronal survival, dendrite arborization, and spine formation [16]. Enhanced BDNF signaling facilitates long-term potentiation (LTP), the primary cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory.

Synaptic Protein Synthesis: VR environments activate mTORC1 signaling pathways, leading to increased synthesis of synaptic proteins such as GluR1, PSD95, and synapsin 1, thereby enhancing synaptic density and function in cortical regions [16] [18].

Glutamatergic System Engagement: Through NMDA receptor activation, VR experiences promote calcium influx that triggers intracellular signaling cascades essential for synaptic modification, mirroring mechanisms targeted by rapid-acting antidepressant compounds [18].

Quantitative Evidence: Electrophysiological and Behavioral Outcomes

EEG Measures of Cortical Reorganization

Recent studies utilizing electroencephalography (EEG) have provided quantitative evidence of VR-induced neuroplasticity at the network level:

Table 1: EEG Spectral Power Changes Following VR Intervention in Chronic Stroke Patients [19]

| EEG Band | Brain Region | Change Post-VR | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theta | Diffuse | No significant change | N/A |

| Alpha | Occipital areas | Significant increase | Visual processing enhancement |

| Beta | Frontal areas | Significant increase | Sensorimotor integration, cognitive control |

| Alpha/Beta Ratio | Primary motor circuit | Significant decrease | Enhanced motor readiness |

This study demonstrated that VR-based cognitive training resulted in significant EEG-related neural improvements in the primary motor circuit, with specific changes in power spectral density and time-frequency domains observed in patients with moderate-to-severe ischemic stroke in the chronic phase (at least 6 months post-event) [19]. The findings suggest that VR interventions can modulate neural oscillations even during late-stage recovery when conventional rehabilitation approaches show limited efficacy.

Clinical and Functional Outcomes

VR interventions produce measurable improvements in functional outcomes across neurological conditions:

Table 2: Functional Outcome Measures Following VR Interventions Across Patient Populations

| Condition | Intervention Type | Outcome Measures | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sclerosis | VR vs. Sensory-Motor training | T25FW, TUG, MSQOL-54 | Significant improvements in both groups (T25FW: P=0.002 SN; P=0.001 VR) | [20] |

| Chronic Stroke | VR-based cognitive training | EEG band power, clinical scales | Significant increase in alpha and beta power; functional improvement | [19] |

| Amblyopia | Dichoptic VR training | Visual acuity, contrast sensitivity | 1-4 lines visual acuity improvement | [21] |

The comparative study in MS patients revealed that both VR and sensory-motor interventions significantly improved Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW) and Timed Up and Go (TUG) performance, with the VR group showing particularly strong improvements in quality of life measures [20]. These functional gains correlate with the neuroplastic changes observed in electrophysiological studies, providing a comprehensive picture of VR-induced recovery mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: VR Cognitive Training for Stroke Rehabilitation

Objective: To evaluate VR-induced neuroplasticity in chronic stroke patients using EEG measures and functional outcomes.

Population: Adults with moderate-to-severe ischemic stroke in chronic phase (>6 months post-stroke); experimental group (n=15, mean age=58.13±8.33) and control group (n=15, mean age=57.33±11.06) [19].

VR System: VRRS Evo-4 machine with customizable cognitive exercises targeting attention, memory, executive functions, and visuo-spatial processing [19].

Intervention Parameters:

- Session Duration: 45-60 minutes

- Frequency: 3 sessions/week

- Total Program: 8 weeks (24 sessions)

- Progression: Gradual increase in task difficulty based on performance

Control Condition: Conventional neurorehabilitation matched for duration and frequency but without VR components.

Outcome Measures:

- Primary Electrophysiological: Resting-state EEG with power spectral analysis of theta, alpha, and beta rhythms

- Secondary Clinical: Oxford Cognitive Screen, Barthel Index, Modified Rankin Scale [19]

Data Analysis:

- Pre-process EEG signals using standardized filters (0.5-45 Hz bandpass, notch filter at 50/60 Hz)

- Compute power spectral density via Fast Fourier Transform

- Compare pre-post changes in absolute and relative band power

- Statistical analysis using repeated measures ANOVA with group (VR vs control) as between-subject factor

Protocol 2: Sensory-Motor Integration Training for Multiple Sclerosis

Objective: To compare effects of VR versus sensory-motor training on gait, balance, and quality of life in MS patients.

Population: MS patients with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores of 2-6 receiving Rituximab therapy; sample size of 30 participants randomized to VR (n=10), sensory-motor (n=10), or control (n=10) groups [20].

VR System: Commercially available VR system with balance and gait activities requiring weight shifting, obstacle avoidance, and dual-task performance.

Intervention Parameters:

- Session Duration: 45 minutes

- Frequency: 3 sessions/week

- Total Program: 8 weeks (24 sessions)

- Intensity: Progressive increase based on participant performance

Control Condition: Routine care without structured balance training.

Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW), Timed Up and Go (TUG)

- Secondary: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life 54 Instrument (MSQOL-54), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [20]

Assessment Timeline: Baseline and post-intervention (8 weeks)

Data Analysis:

- Within-group changes: Paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests

- Between-group differences: ANCOVA adjusting for baseline scores

- Effect sizes calculation using Cohen's d

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Molecular Pathways of VR-Induced Neuroplasticity

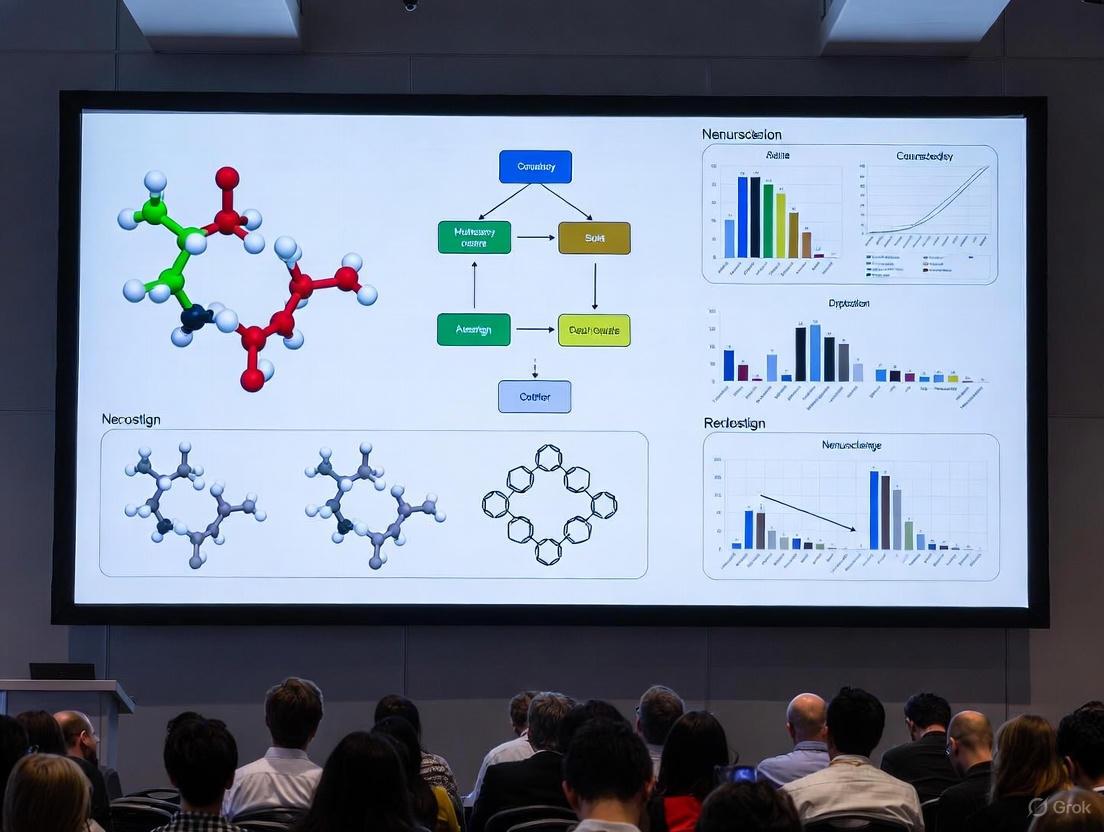

Diagram 1: Molecular pathways of VR-induced neuroplasticity. This pathway illustrates the sequence from multisensory VR stimulation through molecular cascades to functional improvements, highlighting key targets for therapeutic intervention.

Experimental Workflow for VR Neuroplasticity Research

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for VR neuroplasticity research. This workflow outlines a standardized approach for investigating VR-induced neuroplasticity, from participant recruitment through data analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for VR Neuroplasticity Investigations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Platforms | VRRS Evo-4, HMDs (Oculus Rift, HTC Vive), Jintronix | Create controlled, immersive environments for sensory-motor and cognitive training | Level of immersion, tracking precision, feedback capabilities [19] [17] |

| Neuroimaging Systems | EEG systems, fNIRS, fMRI-compatible VR | Quantify neurophysiological changes, functional connectivity, and cortical reorganization | Temporal resolution, spatial resolution, compatibility with movement [19] |

| Behavioral Assessment | Oxford Cognitive Screen, Barthel Index, TUG, T25FW | Evaluate functional outcomes correlated with neuroplastic changes | Sensitivity to change, reliability, validity for population [19] [20] |

| Molecular Assays | BDNF ELISA, synaptic protein Western blots, mTOR pathway markers | Validate molecular mechanisms of VR-induced plasticity in animal models | Specificity, sensitivity, throughput capacity [16] [18] |

| Data Analytics | EEG spectral analysis, kinematic tracking software, statistical packages | Process multimodal data streams and identify significant patterns | Algorithm accuracy, processing speed, visualization capabilities [19] |

VR technology represents a powerful, non-invasive approach to inducing targeted neuroplasticity across sensory-motor pathways and cognitive networks. The protocols and frameworks provided herein offer standardized methodologies for researchers investigating VR-driven neuroplastic changes, with particular utility for preclinical studies of neuroplasticity-enhancing compounds and mechanisms. Future research directions should focus on optimizing VR parameters for specific neural circuits, identifying biomarkers predictive of response, and developing closed-loop systems that adapt in real-time to neural activity for precision neurorehabilitation.

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in behavioral neuroscience, enabling researchers to study context-dependent learning and memory with unprecedented experimental control. Context-dependent memory is defined as the phenomenon where memory recall is stronger when the retrieval environment matches the original environment in which the memory was formed [22]. This encompasses not only external environmental cues but also internal states and temporal elements bound to the learning process.

The theoretical foundation for this work rests on the encoding specificity principle, which states that successful remembering depends on the overlap between encoding and retrieval situations [22]. VR technology allows investigators to create highly distinctive, controlled learning contexts that can be systematically manipulated to examine how contextual cues become bound to memories and facilitate or impair their subsequent recall.

This technological approach has gained significant traction, with bibliometric analyses revealing exponential growth in VR and mental health publications since 2020, featuring robust international collaboration networks and diverse research clusters spanning virtual reality, exposure therapy, mild cognitive impairment, and serious games [23]. The integration of VR into neuroscience research represents a paradigm shift from traditional maze-based assays to automated, precisely controlled systems that offer enhanced compatibility with large-scale neural recording techniques [24].

Comparative VR Platforms in Animal and Human Research

Rodent VR Platforms for Context-Dependent Research

Recent advances in rodent VR systems have addressed previous limitations in flexibility and performance. The platform developed by Xu Chun's Lab exemplifies this progress, featuring a high-performance system assembled from modular hardware and custom-written software with upgradability [25] [26]. This system includes six curved LCD screens covering a 270° view angle, a styrofoam cylinder for locomotion, a motion detector, and integrated neural recording capabilities [26].

The key advantage of this approach is the maximized experimental control it provides over contextual elements while maintaining compatibility with head-fixed neural recordings. Using this platform, researchers have successfully trained mice to perform context-dependent cognitive tasks with rules ranging from discrimination to delayed-sample-to-match while recording from thousands of hippocampal place cells [25]. Through precise manipulations of context elements, investigators discovered that context recognition remained intact with partial context elements but was impaired by exchanges of context elements between different environments [25].

Human VR Platforms for Contextual Memory Research

Human VR research utilizes both fully immersive head-mounted displays and desktop-based systems, with the latter offering better compatibility with neuroimaging techniques [27]. These platforms create controlled virtual environments that serve as contextual backgrounds for learning episodes. In a notable study on foreign vocabulary learning, participants navigated through distinctive desktop VR contexts while learning words from two phonetically similar languages [28].

A critical factor in human VR research is the concept of "presence" – the user's subjective experience of the VR environment as a place they have actually inhabited rather than merely watching passively [28]. This sense of presence appears to modulate the strength of context-dependent memory effects, with those experiencing higher levels of presence showing stronger contextual facilitation of memory.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of VR Platforms in Rodent and Human Research

| Feature | Rodent VR Platform | Human VR Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Display System | Six curved LCD screens (270° view) [25] | Head-mounted displays or desktop systems [27] |

| Locomotion Interface | Styrofoam cylinder [25] | Hand controllers, keyboard, or physical walking [27] |

| Performance | High frame rate; real-time processing [25] | Varies by system; desktop-based common for neuroimaging [27] |

| Neural Recording Compatibility | Large-scale hippocampal recording [25] | EEG, fMRI, MEG compatibility [28] |

| Key Advantage | Precise control of contextual elements [25] | Balance between control and ecological validity [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Rodent Context Discrimination Task

Objective: To investigate how mice recognize and respond to distinct virtual contexts, and how manipulation of contextual elements affects behavior and neural representations.

Animals: Adult C57BL/6J mice (>8 weeks old) are housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum until water restriction begins for behavioral training [25].

Surgical Procedures:

- Implant a custom-made head plate fixed to the skull with dental acrylic for head-fixation during VR training [25].

- For calcium imaging, inject AAV2/9-CaMKII-GCaMP6f vector into hippocampal CA1 using stereotactic coordinates (AP: -1.82 mm, ML: -1.5 mm, DV: -1.5 mm relative to bregma) [25].

- Two weeks post-injection, implant a GRIN lens above the injection site during a second surgery [25].

Behavioral Training:

- Pre-training: After 1-2 days of water restriction, habituate mice to running on a rotating Styrofoam cylinder. Gradually introduce black-and-white gratings on a VR linear track, starting with a 25-cm track and progressively extending to 100 cm as the mouse achieves >70 trials per session [25].

- Context Discrimination Training: Train mice in a linear track (100 cm) consisting of an 80-cm context and a 20-cm corridor. The context is composed of four visual elements: left/right walls, top floor (ceiling), and front door, with distinct versions for different contexts [25].

- Reward Paradigm: Associate water reward with specific context areas. Mice receive reward (1.5-2.0 μL per drop) for licking in the correct context according to the task rules [25].

Data Collection:

- Monitor licking behavior as an indicator of context recognition.

- Record neural activity using calcium imaging during VR navigation.

- Analyze place cell responses to different contextual elements [25].

Human Context-Dependent Memory Protocol

Objective: To examine how distinctive VR learning contexts affect the acquisition, interference, and retention of similar materials, and the role of mental context reinstatement in recall.

Participants: Native English speakers without prior knowledge of Swahili or Chinyanja, typically aged 18-35 years.

VR Environment Setup:

- Create two highly distinctive desktop VR environments using 3D modeling software.

- Ensure environments are visually distinct but equally complex to avoid confounds [28].

Experimental Procedure:

- Group Assignment: Randomly assign participants to single-context (learn both languages in one VR environment) or dual-context (learn each language in its unique VR environment) groups [28].

- Learning Phase: Across two consecutive days, participants encode 80 foreign vocabulary items from two phonetically similar Bantu languages (Swahili and Chinyanja).

- Testing Phase:

- Conduct initial tests within the learning context(s) as participants navigate along a predetermined path.

- Administer transfer test outside of the learning context (without VR) to assess generalization.

- Implement controlled mental reinstatement protocol before each recall trial in transfer test [28].

- fMRI Component (for neural reinstatement analysis):

- Scan dual-context participants during recall using fMRI.

- Measure reinstatement of brain activity patterns associated with original encoding contexts [28].

Data Collection:

- Record recall accuracy for vocabulary items.

- Measure intrusion errors (producing translation from wrong language).

- Administer presence questionnaire to assess subjective experience of VR environments [28].

- Collect fMRI data during retrieval attempts.

Key Findings and Data Analysis

Quantitative Outcomes Across Species

Research using VR platforms has yielded robust quantitative data on context-dependent memory processes in both rodent and human models.

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Context-Dependent Memory Tasks

| Measure | Rodent Studies | Human Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Performance | Successful learning of context-dependent rules (discrimination to delayed-sample-to-match) [25] | 42% (±17%) recall of foreign words after two exposures [28] |

| Context Manipulation Effects | Context recognition intact with partial elements; impaired by exchanges of elements [25] | 92% retention in dual-context vs 76% in single-context after one week [28] |

| Transfer Performance | N/A | 48% (±18%) recall during non-VR transfer test [28] |

| Physical Movement Benefit | N/A | Significantly better spatial memory in walking vs stationary conditions [27] |

Neural Mechanisms of Context-Dependent Memory

The hippocampus plays a central role in context-dependent memory across species, coding for and detecting novel contexts [22]. In rodents, researchers have recorded from thousands of hippocampal place cells during VR navigation, revealing how these cells represent different contextual elements [25]. The interaction of multiple brain regions including the perirhinal cortex, lateral entorhinal cortex, medial entorhinal cortex, postrhinal cortex, and the hippocampus processes different types of contextual information [22].

Human neuroimaging studies using fMRI have confirmed that reinstatement of brain activity patterns associated with the original encoding context during word retrieval is associated with improved recall performance [28]. This neural reinstatement appears to be a key mechanism supporting context-dependent memory.

Research comparing physical versus virtual navigation has demonstrated that stationary VR paradigms may disrupt typical neural representations of space. Studies utilizing augmented reality (AR) to enable physical movement during spatial memory tasks have found evidence for increased amplitude of theta oscillations during walking compared to stationary conditions, suggesting enhanced engagement of hippocampal networks during ambulatory navigation [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Technologies

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Modular VR Platform | Provides customizable virtual environments with controlled contextual elements | Rodent context discrimination tasks [25] |

| Desktop VR System | Presents immersive environments compatible with neuroimaging | Human vocabulary learning studies [28] |

| Calcium Imaging | Records neural activity from large populations of cells | Monitoring hippocampal place cells in rodents [25] |

| fMRI | Measures brain-wide activity patterns during cognitive tasks | Assessing neural reinstatement in humans [28] |

| AR Spatial Memory Task | Enables study of spatial memory with physical movement | Comparing ambulatory vs. stationary navigation [27] |

| Presence Questionnaire | Quantifies subjective experience of VR environments | Assessing relationship between presence and memory [28] |

Methodological Considerations and Technical Implementation

Implementation Workflow

Successful implementation of VR platforms for context-dependent memory research requires careful attention to technical details and methodological considerations.

Comparative Platform Specifications

The technical specifications of VR platforms significantly influence their applicability for different research questions. Rodent systems prioritize compatibility with neural recording techniques, with custom-built platforms offering high frame rates and real-time processing capabilities that support precise experimental control during large-scale neural recordings [25]. These systems typically employ multiple curved LCD screens covering up to 270° to create immersive environments, with locomotion captured through motion detection of a styrofoam cylinder [26].

Human research platforms balance immersion with practical constraints, utilizing either head-mounted displays for full immersion or desktop systems for better neuroimaging compatibility [27]. A critical consideration in human research is the measurement of "presence" - the subjective experience of the virtual environment as real - which appears to modulate context-dependent memory effects [28].

Emerging evidence suggests that physical movement during encoding and retrieval enhances spatial memory performance compared to stationary VR paradigms [27]. This has important implications for platform selection, with augmented reality (AR) approaches offering a promising middle ground by allowing physical navigation while maintaining experimental control through virtual object overlay in real environments.

VR platforms have revolutionized the study of context-dependent learning and memory across species, enabling unprecedented experimental control while maintaining ecological validity. The complementary approaches of rodent and human research have yielded insights into the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying context-dependent memory, highlighting the central role of the hippocampus and related medial temporal lobe structures.

Future directions include further integration of VR with advanced neural recording techniques, development of more sophisticated contextual manipulation paradigms, and translation of basic research findings into clinical applications for conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, PTSD, and other disorders characterized by context-dependent memory impairments [22]. The continued refinement of VR platforms promises to further enhance our understanding of how environmental contexts shape learning and memory across species.

From Lab to Clinic: Methodological Advances and Therapeutic Applications in Neuropsychiatry and Rehabilitation

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a transformative tool in behavioral neuroscience and mental health research, offering unprecedented capabilities for both symptom assessment and therapeutic intervention. By creating immersive, computer-generated environments, VR enables researchers and clinicians to study and treat psychiatric conditions with a level of ecological validity and experimental control previously unattainable in traditional laboratory or clinical settings [29]. The fundamental strength of VR lies in its ability to transport individuals into simulated worlds that feel authentic while allowing precise manipulation of environmental variables and real-time capture of behavioral, physiological, and cognitive data [29] [30]. This capability is particularly valuable for disorders such as psychosis, ADHD, and anxiety disorders, where symptoms are often context-dependent and difficult to reliably elicit in standard assessment environments.

The theoretical underpinnings of VR therapy draw from multiple psychological frameworks, with cognitive-behavioral principles forming a central foundation. For anxiety disorders, VR facilitates graded exposure therapy by presenting fear-eliciting stimuli in a controlled, safe environment, enabling inhibitory learning and extinction [30]. In psychosis research, VR allows experimental manipulation of social environments to study paranoid ideation and social cognitive processes [29]. For ADHD, VR-based interventions leverage principles of neuroplasticity and reinforcement learning to target deficits in attentional control, cognitive flexibility, and self-regulation [31]. The technology also aligns with the cognitive-energetic model of ADHD, which addresses deficits in motivational regulation that can be targeted through adaptive, immersive tasks [31].

A significant advancement in the field has been the development of standardized frameworks for VR clinical trials. The Virtual Reality Clinical Outcomes Research Experts (VR-CORE) committee has established a phased model mirroring pharmaceutical development pipelines [15]. This framework includes VR1 studies focusing on content development through human-centered design, VR2 studies assessing feasibility and initial efficacy, and VR3 studies comprising rigorous randomized controlled trials [15]. This systematic approach ensures methodological rigor in developing and validating VR interventions across mental health conditions.

Clinical Applications and Empirical Evidence

VR for Anxiety Disorders

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) represents the most established application of VR in mental health treatment. VRET operates on the same principles as traditional exposure therapy but delivers controlled exposures through immersive simulation rather than imagination or in vivo confrontation [30]. This approach offers distinct advantages, particularly for situations where real-world exposure is impractical, costly, or dangerous (e.g., fear of flying, combat-related PTSD) [30]. Meta-analyses comparing VRET to both control conditions and traditional evidence-based treatments for anxiety disorders consistently demonstrate medium-to-large effect sizes [8].

The efficacy of VRET stems from its ability to create a strong sense of presence while maintaining clinician control over the exposure parameters. Patients understand the virtual environment is artificial, yet their psychological and physiological responses mirror those experienced in real-life situations [30]. This phenomenon enables effective fear activation and subsequent extinction learning while providing patients with a greater sense of control, as they can terminate the experience at any moment [30]. Research indicates that this controllability enhances self-efficacy and may improve treatment adherence compared to traditional methods.

Table 1: Empirical Support for VRET in Anxiety Disorders

| Disorder | Research Findings | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Phobias | Significant reduction in fear and avoidance behaviors; equivalent effects to in vivo exposure for acrophobia, aviophobia, spider phobia [30]. | Strong: Multiple RCTs and meta-analyses |

| Social Anxiety | Customized social scenarios effectively trigger anxiety; enables practice of social skills; reduces symptom severity [30]. | Moderate: Growing evidence base |

| PTSD | Enables controlled re-experiencing of traumatic memories; effective alternative for treatment-resistant cases [30]. | Moderate: Supported by RCTs |

| Panic Disorder | Safe exposure to interoceptive and situational triggers in controlled environment; reduces panic frequency and severity [8]. | Moderate: Evidence from clinical trials |

VR for Psychosis

VR applications for psychosis represent a innovative approach to studying and treating symptoms that are difficult to assess through traditional methods. Researchers have developed virtual environments specifically designed to elicit and measure paranoid ideation, social avoidance, and interpretive biases in controlled settings [29]. For example, participants can be immersed in a virtual subway train or elevator populated by neutral avatars, allowing researchers to objectively quantify paranoid responses to ambiguous social stimuli [29].

These paradigms enable precise experimental manipulations that illuminate underlying mechanisms. One seminal study placed participants in two conditions: one where they were taller than other virtual characters and another where they were shorter [29]. Results demonstrated that in the shorter condition, participants reported more negative social comparison and greater paranoia, with social comparison fully mediating the relationship between height manipulation and paranoid feelings [29]. This suggests that negative perceptions of self relative to others may drive paranoid ideation.

VR also shows promise for intervention in psychosis. Beyond assessment, virtual environments can be used for social skills training, allowing individuals to practice social interactions in a safe, graded manner. Cognitive remediation approaches using VR can target specific cognitive deficits associated with psychosis, such as executive functioning and social cognition [30]. The ability to customize difficulty levels and provide immediate feedback makes VR particularly suitable for these therapeutic applications.

VR for ADHD

VR-based interventions for ADHD represent a paradigm shift from conventional approaches, addressing core neurocognitive deficits through immersive, adaptive training environments. Unlike traditional cognitive training, VR can create ecologically valid scenarios that mimic real-world challenges with attentional control, impulse regulation, and task persistence [31]. These simulations can be systematically graded in difficulty and tailored to individual symptom profiles, providing optimal challenges that promote neuroadaptive plasticity [31].

Theoretical models informing VR interventions for ADHD include Barkley's executive dysfunction model and the dual-pathway model, which emphasize deficits in inhibitory control, sustained attention, and motivational regulation [31]. VR environments can target these domains through carefully designed tasks that require continuous performance, response inhibition, and cognitive flexibility within distracting contexts. The reinforcing properties of immersive gaming elements can enhance engagement and adherence, particularly important for pediatric populations [31].

Preliminary research indicates promising applications across the lifespan. For children with ADHD, VR classrooms can assess and train sustained attention despite typical classroom distractions [31]. For adults, VR can simulate workplace environments to practice organizational skills and time management. However, the evidence base remains emergent, with researchers calling for more rigorous randomized controlled trials comparing VR interventions to established treatments [31].

Table 2: VR Applications Across Psychiatric Disorders

| Disorder | Assessment Applications | Therapeutic Applications | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders | Behavioral avoidance; physiological reactivity; subjective distress [29] | Graded exposure; extinction learning; self-efficacy enhancement [30] | Controlled exposure; emotional processing; inhibitory learning |

| Psychosis | Paranoid ideation; social distance; interpretation biases [29] | Social skills training; reality testing; cognitive remediation [30] | Normalization of experiences; social cognitive training; behavioral experiment |

| ADHD | Sustained attention; impulse control; cognitive flexibility [31] | Cognitive training; behavioral inhibition; self-regulation [31] | Neuroplasticity; reinforcement learning; attentional control |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Framework

VR Clinical Trial Phases (VR-CORE Model)

The VR-CORE framework provides a structured methodology for developing and testing VR interventions, ensuring scientific rigor comparable to pharmaceutical trials [15]. The model comprises three distinct phases:

VR1 Studies: Content Development VR1 studies focus on intervention development using human-centered design principles. This phase emphasizes deep engagement with patient and provider stakeholders to ensure relevance, usability, and therapeutic alignment [15]. Key activities include:

- Recruitment of diverse patient populations representing varying ages, comorbidities, and technological comfort levels

- Observation of patients in clinically relevant contexts to understand behavioral patterns and environmental influences

- Individual interviews and focus groups to identify needs, struggles, expectations, and treatment preferences

- Expert interviews with clinicians to integrate therapeutic expertise and clinical practicality

- Journey mapping to define the sequence of events patients will experience within the VR intervention [15]

This participatory design process helps avoid technological solutions that fail to address genuine clinical needs or align with therapeutic mechanisms.

VR2 Studies: Feasibility and Initial Efficacy VR2 trials conduct early-stage testing to establish feasibility, acceptability, tolerability, and preliminary clinical effects [15]. These studies typically employ smaller sample sizes and focus on:

- Acceptability metrics: Patient satisfaction, perceived usefulness, and willingness to continue treatment

- Feasibility indicators: Recruitment rates, completion rates, protocol adherence, and implementation barriers

- Tolerability assessment: Incidence of cybersickness, emotional distress, or other adverse effects

- Clinical outcomes: Preliminary evidence of symptom reduction using validated measures

- Dose-response relationships: Optimal session duration, frequency, and total treatment length [15]

VR2 studies provide essential data for refining interventions and informing power calculations for subsequent randomized trials.

VR3 Studies: Randomized Controlled Trials VR3 trials constitute full-scale randomized controlled studies comparing the VR intervention to appropriate control conditions [15]. Methodological considerations include:

- Control group selection: Active controls (standard care, alternative treatments) or attention-placebo controls

- Blinding procedures: While participants cannot be blinded to VR exposure, outcome assessors and statisticians should remain blinded

- Primary outcomes: Clinically meaningful endpoints validated for the target population

- Sample size justification: Adequate power based on VR2 effect size estimates

- Generalizability: Inclusion criteria reflecting real-world patient diversity [15]

These trials provide the definitive evidence base for clinical efficacy and guide implementation decisions.

Protocol for VR Exposure Therapy in Anxiety Disorders

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for implementing VRET for anxiety disorders, adaptable to specific phobias, social anxiety, and PTSD:

Session 1: Psychoeducation and Treatment Rationale

- Establish therapeutic alliance and explain VR technology

- Present treatment rationale based on exposure principles

- Develop individualized fear hierarchy with patient input

- Introduce coping strategies (e.g., diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive restructuring)

- Conduct brief VR orientation with neutral environment

Sessions 2-8: Graduated Exposure

- Begin with least feared scenario from hierarchy

- Use subjective units of distress (SUDS) ratings every 2-3 minutes

- Continue exposure until SUDS decreases by 50% within session

- Progress to next hierarchy item when SUDS stabilizes at low level

- Vary exposure parameters to enhance generalization (e.g., different virtual contexts, stimulus intensities)

Session 9: Relapse Prevention

- Review progress and skills acquired

- Develop maintenance plan for continued practice

- Address anticipatory anxieties about real-world application

- Schedule booster sessions if indicated [30] [8]

Throughout treatment, clinicians should monitor for cybersickness and adjust protocols accordingly. Between-session practice, either in vivo or with take-home VR systems, enhances generalization of treatment gains.

VR Exposure Therapy Clinical Protocol

Protocol for VR Social Stress Paradigm in Psychosis Research

This protocol details the implementation of a VR social stress test for assessing paranoid ideation, adaptable for both research and clinical assessment purposes:

Environment Setup

- Create a socially challenging virtual environment (e.g., subway car, elevator, cafe)

- Populate with neutral avatars with pre-programmed behaviors

- Standardize avatar appearance, number, and proximity to participant

- Implement eye-tracking and movement tracking capabilities

Experimental Conditions

- Neutral condition: Avatars display neutral expressions and behaviors

- Stress condition: Manipulate social stressors (e.g., avatar height differences, direct gaze, crowded spaces)

- Control condition: Minimal social stimuli for baseline comparison

Assessment Measures

- Primary outcome: Paranoia scale scores post-exposure

- Behavioral measures: Interpersonal distance, eye contact avoidance, escape behaviors

- Physiological measures: Heart rate variability, galvanic skin response synchronized with VR events

- Cognitive measures: Interpretation biases, social threat appraisal [29]

Procedure

- Baseline assessment (pre-VR symptoms, physiological measures)

- VR orientation (neutral environment)

- Randomized exposure to experimental conditions (counterbalanced)

- Continuous symptom ratings during exposure

- Post-exposure debriefing and assessment

This protocol enables precise quantification of paranoid responses to social stimuli while controlling for environmental variables that confound real-world assessment.

Implementation Framework and Technical Considerations

Successful implementation of VR in clinical research and practice requires attention to technical specifications, ethical considerations, and practical barriers. The following framework addresses key implementation components:

Equipment Selection and Technical Specifications

Choosing appropriate VR hardware represents a critical first step in developing VR research or clinical programs. Key considerations include:

Head-Mounted Display (HMD) Selection

- Display resolution: Higher resolution reduces screen-door effect and enhances presence

- Refresh rate: ≥90Hz minimizes latency and reduces cybersickness risk

- Tracking capabilities: Inside-out vs. external sensor tracking based on mobility needs

- Comfort and adjustability: Particularly important for extended sessions

- Integrated sensors: Eye-tracking, facial expression analysis enhance research utility

Software and Development Platforms

- Game engines: Unity or Unreal Engine for custom environment development

- Content availability: Pre-built environments for common phobias and scenarios

- Customization capacity: Ability to modify environments for individual needs

- Data export functionality: Compatibility with statistical analysis packages

Accessory Equipment

- Physiological monitoring: Heart rate, GSR, EEG synchronization capabilities

- Input devices: Hand controllers, data gloves for interaction tracking

- Safety equipment: Boundary systems for room-scale VR [8]

Table 3: Technical Specifications for Research-Grade VR Systems

| Component | Minimum Specification | Optimal Specification | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMD Resolution | 1280×1440 per eye | 1920×2160 per eye | All applications; critical for presence |

| Refresh Rate | 90Hz | 120Hz | Reduces cybersickness; enhances realism |

| Field of View | 100° | 110°-130° | Peripheral relevance for anxiety contexts |

| Tracking | Rotational + positional | Room-scale with sub-millimeter precision | Social interaction studies; movement analysis |

| Eye Tracking | Not required | 60-120Hz sampling rate | Attention research; social gaze monitoring |

| Audio | Integrated headphones | Spatial 3D audio | Environmental immersion; auditory processing |

Ethical Considerations and Risk Management

VR implementation raises unique ethical considerations that require proactive management:

Privacy and Data Security

- VR systems capture extensive behavioral and physiological data requiring protection

- Implement encryption for data storage and transmission

- Develop clear data retention and disposal policies

- Obtain informed consent specifically addressing biometric data collection [31]

Psychological Risk Mitigation

- VR exposure may temporarily increase anxiety or trigger emotional reactions

- Establish protocols for session termination and distress management

- Screen for contraindications (e.g., seizure disorders, severe dissociation)

- Provide adequate debriefing following emotionally challenging exposures [30]

Equity and Access

- High equipment costs may limit accessibility in resource-constrained settings

- Consider mobile-based VR alternatives to enhance dissemination

- Address technological literacy barriers through simplified interfaces

- Develop culturally adapted content for diverse populations [31]

Clinical Governance

- Establish competency standards for VR-assisted therapy

- Develop supervision protocols for novice clinicians

- Create maintenance procedures for equipment sanitation and functionality [8]

Implementing VR research requires both technical equipment and methodological resources. The following toolkit outlines essential components for establishing a VR research program:

Table 4: Essential VR Research Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Hardware Platforms | HTC VIVE Pro Eye, Oculus Rift S, Varjo VR-3 | Display immersive environments; track user movement/behavior | Resolution, refresh rate, FOV, integrated sensors, comfort |

| VR Development Software | Unity 3D, Unreal Engine, VRTK | Create custom virtual environments; program interactive elements | Learning curve, asset availability, compatibility with analysis tools |

| Behavioral Data Capture | Eye-tracking modules, motion capture, controller input | Quantify attention, movement, interaction patterns | Sampling rate, data synchronization, export formats |

| Physiological Monitoring | BioPac Systems, Empatica E4, Shimmer GSR+ | Objective arousal measures (HRV, EDA, EMG) | Wireless operation, synchronization with VR events, data quality |

| Quantitative Analysis Tools | R, Python, Displayr, SPSS | Statistical analysis of behavioral, subjective, physiological data | Handling multimodal data streams, visualization capabilities |

| Experimental Design Frameworks | VR-CORE guidelines [15] | Phase-appropriate study design (VR1, VR2, VR3) | Regulatory compliance, methodological rigor, stakeholder engagement |

VR Research Program Core Components

Successful VR research programs integrate multiple technical systems within a rigorous methodological framework. The hardware platform forms the foundation for delivering immersive experiences, while development software enables environment customization. Behavioral and physiological capture systems provide objective outcome measures, with analysis tools facilitating data interpretation. Throughout this process, established design frameworks like the VR-CORE model ensure scientific rigor and clinical relevance [15]. This integrated approach enables researchers to leverage VR's unique capabilities while maintaining methodological standards required for advancing evidence-based mental health interventions.

Integrating VR with Neurofeedback and EEG for Real-Time Neural Self-Regulation

The integration of virtual reality (VR), electroencephalography (EEG), and neurofeedback (NFB) represents a transformative frontier in behavioral neuroscience research. This synergy creates closed-loop systems capable of monitoring and modulating brain function within controlled, yet ecologically valid, immersive environments [32] [33]. Such neuroadaptive technology enables real-time neural self-regulation, where a user's brain signals directly influence elements of a virtual world, facilitating operant learning of brain activity patterns [34] [35]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this paradigm offers a powerful tool for investigating neural correlates of behavior and testing the efficacy of neurotherapeutic interventions with a level of precision and engagement previously unattainable [34] [36]. The field is rapidly advancing due to hardware miniaturization, the development of dry electrodes, and the commercial availability of high-quality head-mounted displays (HMDs), making sophisticated VR-EEG setups more accessible and practical for research and clinical applications [33].

Application Notes: Efficacy and Mechanisms

The combined application of VR and EEG-NFB is being explored across a wide spectrum of health conditions and cognitive domains. Understanding its evidenced efficacy and underlying mechanisms is crucial for designing robust experiments.

Documented Efficacy Across Domains

A recent systematic review assessed the efficacy of VR-based EEG-NFB for relieving health-related symptoms, classifying it according to established guidelines for psychophysiological interventions. The findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Efficacy of VR-Based EEG Neurofeedback for Health-Related Symptom Relief

| Domain | Efficacy Classification | Key Findings and Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Probably Efficacious | Shows promise for conditions like ADHD, potentially offering a more engaging alternative to traditional cognitive training [34]. |

| Emotions & Mood | Possibly Efficacious | Applied for anxiety disorders and depression; VR allows for graded exposure and emotional regulation in personalized scenarios [34] [3]. |

| Anxiety Disorders | Supported by Meta-Reviews | VR exposure therapy favorably compares to existing treatments for anxiety, phobias, and PTSD, with long-term effects generalizing to the real world [3]. |

| Pain Management | Possibly Efficacious | VR's immersive nature is a proven distractor from acute pain; NFB may enhance this by teaching self-regulation of neural circuits involved in pain perception [34] [3]. |

| Relaxation | Possibly Efficacious | Used for stress reduction; immersive natural environments paired with NFB on rhythms like SMR can enhance physical relaxation and mental alertness [34] [35]. |

| Other Domains (Impulsiveness, Memory, etc.) | Possibly Efficacious | Preliminary evidence supports investigation into impulsiveness (e.g., in ADHD), memory (post-stroke rehabilitation), and self-esteem [34]. |

Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Action

The potency of integrated VR-NFB stems from its engagement of key neurocognitive processes:

Embodied Simulation and Presence: Neuroscience suggests the brain uses embodied simulations to regulate the body and predict actions, concepts, and emotions [3]. VR operates on a similar principle, providing a sensory simulation that predicts the user's movements, thereby inducing a strong sense of presence—the subjective feeling of "being there" in the virtual environment [3] [37]. This presence is crucial for eliciting genuine cognitive and emotional responses, making therapy and assessment more ecologically valid [38]. Research indicates that a decreased power in the parietal alpha rhythm is a neurophysiological correlate of an increased sense of presence, suggesting a direct link between specific brain activity and the subjective VR experience [37].

Enhanced Motivation and Engagement: Traditional NFB tasks can be repetitive and demotivating [34]. Integrating NFB into an immersive, game-like VR environment significantly increases user motivation, interest, and adherence to training protocols [34] [35]. For instance, stroke patients undergoing VR-NFB rehabilitation reported high enjoyability and a desire to continue training beyond the required period [35].

Targeting "Hot Cognitions": Traditional cognitive therapies often rely on "cold cognitions"—abstract self-reflection detached from emotional arousal. VR-NFB allows for a "symptom capture" approach, where therapy is applied while the symptom is actively being elicited in a controlled virtual space [36]. This allows individuals to practice regulation strategies against "hot" (emotionally charged) cognitions, which may lead to more robust and generalizable learning [36].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing VR-EEG-NFB experiments, from basic research to clinical application.

Protocol 1: Basic SMR Up-Regulation with 3D vs. 2D Feedback

This protocol is adapted from a sham-controlled study investigating the effect of feedback modality on NFB performance [35].

Aim: To compare the efficacy of a 3D VR-based feedback paradigm against a conventional 2D bar feedback paradigm for up-regulating the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR, 12-15 Hz) in a single training session.

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Materials for SMR Up-Regulation Protocol

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| EEG Amplifier | g.tec gUSBamp RESEARCH amplifier or equivalent, sampling rate ≥ 256 Hz [35]. |

| EEG Electrodes | 16 active Ag/AgCl electrodes (including F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, Pz, EOG channels); gel-based for optimal signal quality [35]. |

| VR Headset | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) capable of running custom paradigms (e.g., Oculus Rift, HTC Vive) [35]. |

| Software | Real-time signal processing software (e.g., BCILab, OpenVIBE) and a 3D game engine (Unity, Unreal Engine) for creating feedback environments [33]. |

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Apply EEG electrodes according to the 10-20 system. The primary feedback electrode is Cz. Impedances for scalp electrodes should be kept below 5 kΩ [35].

- Baseline Recording (3 minutes): Participants watch the feedback paradigm move autonomously while relaxing. The individual mean and standard deviation of SMR (12-15 Hz) power from this run are calculated to set the initial threshold for NFB. Thresholds for Theta (4-7 Hz) and Beta (16-30 Hz) are also set for artifact control [35].

- Group Randomization: Randomly assign participants to one of four groups: 2D Real Feedback, 2D Sham Feedback, 3D Real Feedback, or 3D Sham Feedback [35].

- Feedback Training (6 runs of 3 minutes each):

- 2D Group: Participants see a simple bar on the VR headset. They are instructed to increase the bar's height by generating the correct mental state [35].

- 3D Group: Participants are immersed in a virtual forest environment. They control a ball rolling along a path; successful SMR up-regulation moves the ball forward [35].

- Real Feedback: The visual feedback is directly controlled by the participant's live SMR power.

- Sham Feedback: The visual feedback is pre-recorded or yoked to another participant's performance, unbeknownst to the participant [35].

- Instructions: Instruct participants to be physically relaxed, minimize blinking, and find a mental strategy to increase SMR power.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the average SMR power for each feedback run. Perform a repeated-measures ANOVA with factors Group (2D vs. 3D) and Feedback Type (Real vs. Sham) on the SMR power across runs.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Targeted Intervention for Auditory Verbal Hallucinations (AVH)

This protocol outlines a pilot study for a novel hybrid therapy ("Hybrid") for psychosis, integrating VR, NFB, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [36].

Aim: To investigate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a hybrid VR-NFB-CBT intervention for reducing distress from auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) in individuals with psychosis.

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Materials for AVH Intervention Protocol

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| EEG System | Portable EEG system with capability for real-time beta power analysis. |

| VR Headset & Software | HMD with software to create and customize virtual environments that simulate a patient's specific AVH triggers [36]. |

| Clinical Assessment Tools | Standardized scales for AVH severity (e.g., Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales, PSYRATS) and general psychopathology (e.g., PANSS). |

Procedure:

- Screening & Personalization: Recruit participants with persistent AVHs. Conduct in-depth interviews to identify idiosyncratic triggers (e.g., specific social situations, environments) and characteristics of the voices. Use this information to personalize the VR environments [36].