Virtual Reality in Rodent Navigation Research: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions for Neuroscience and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Virtual Reality (VR) methodologies for studying rodent navigation behavior, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Virtual Reality in Rodent Navigation Research: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions for Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Virtual Reality (VR) methodologies for studying rodent navigation behavior, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles establishing VR as a controlled and ethical tool for behavioral neuroscience. The review details cutting-edge hardware and software systems, from miniature headsets to projection domes, and their application in studying spatial memory, decision-making, and disease models. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for system design and data collection. Finally, the article presents rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with physical mazes, synthesizing key takeaways and outlining future directions for integrating VR into biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

The New Frontier: How VR is Revolutionizing Fundamental Rodent Behavior Research

Virtual Reality (VR) systems for rodent navigation behavior research represent a powerful tool for investigating the neural mechanisms of spatial cognition. A critical distinction in these systems is whether they operate in an open-loop or closed-loop manner. In an open-loop system, the virtual environment (VE) updates according to a pre-programmed script, independent of the animal's behavior. In a closed-loop system, the VE updates in real-time based on sensory feedback of the animal's voluntary movements. This closed-loop design is fundamental for creating a sense of immersion, as it preserves the contingent relationship between an animal's actions and the sensory feedback it receives, more closely mimicking natural navigation [1].

This integration is crucial for studying authentic spatial navigation. In intact rodents, self-motion generates a variety of non-visual cues relevant to path integration, a key navigation mechanism [2]. Closed-loop VR systems aim to provide visual cues that can substitute for these missing physical self-motion cues, allowing researchers to isolate and study the contributions of specific sensory modalities to spatial learning and memory [2] [1]. These systems are therefore indispensable within a broader thesis on VR methods, as they enable unprecedented experimental control while maintaining the behavioral relevance necessary for translational research in neuroscience and drug development.

Core Principles and Quantitative Data

The Principle of Closed-Loop Sensory Stimulation

Closed-loop sensory stimulation creates an immersive experience by forming a real-time feedback cycle. The rodent's locomotion on a spherical treadmill or similar device is tracked. This movement data is instantly fed into a rendering engine, which updates the visual scenery. The updated visual flow (optic flow) is then presented back to the animal, creating a perception of moving through a coherent space [2] [1]. This principle ensures that the rodent's brain receives synchronized visual and self-motion signals, which is a prerequisite for the formation of stable spatial representations.

Efficacy of Visual Landmarks in Spatial Learning

Research has quantitatively demonstrated that vivid visual landmarks within a closed-loop VR system are sufficient for rodents to learn spatial navigation tasks. The tables below summarize key behavioral findings from probe trials that tested spatial learning.

Table 1: Performance Improvement in Probe Trials with Vivid vs. Bland Visual Cues

| Experimental Group | Change in Midzone Crossing Frequency | Change in Virtual Reward Frequency | Increase in Dwell Time at Reward Zones |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vivid Landmarks | Significant increase (P < 0.001) [2] |

Significant increase (P < 0.01) [2] |

Significant increase (P < 0.02) [2] |

| Bland Landmarks | No significant change (P > 0.05) [2] |

No significant change (P > 0.05) [2] |

No significant change (P > 0.05) [2] |

Table 2: Behavioral Metrics During VR Training Sessions Over 3 Days

| Performance Metric | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Distance Between Rewards | 100% (Baseline) | 69.8% ± 5.7% | 70.8% ± 5.0% | P < 0.01 on Day 3 [2] |

| Reward Interval Coefficient of Variation | 0.97 ± 0.09 | Not Reported | 0.80 ± 0.06 | P < 0.05 (Day 1 vs. Day 3) [2] |

| Midzone Crossing Frequency | Baseline | Significant Increase | Significant Increase | P < 0.01 on Day 2, P < 0.02 on Day 3 [2] |

These data show that mice can learn to navigate to specific locations using only visual cues, but only when those cues are vivid and distinctive. Mice operating in bland environments or without visual feedback failed to show similar performance improvements [2].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing two primary rodent VR paradigms: the head-fixed linear track and the freely moving spherical treadmill (Servoball).

Protocol 1: Head-Fixed Spatial Navigation on a Linear Virtual Track

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating hippocampus-dependent goal localization in head-fixed mice [2] [3].

Application: Ideal for studies requiring precise control of the animal's head position for techniques such as in vivo electrophysiology, two-photon calcium imaging, or optogenetic manipulation during spatial behavior.

Materials: See Section 5.1 for details on required reagents and solutions.

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Water-restrict mice according to institutional animal care protocols. Habituate mice to head-fixation on the spherical treadmill over several short sessions.

- System Setup: Configure a torque-neutral, air-levitated spherical treadmill. Position a computer monitor in front of the mouse to display the virtual environment. Calibrate the treadmill's motion sensors to accurately translate the ball's rotation into forward/backward movement in the linear track VE.

- Pre-training (Habituation): Allow the mouse to explore a simple virtual linear track. Automatically deliver a small water reward at both ends of the track to associate the goal zones with reward.

- Bidirectional Training: Train the mouse to run back and forth on the track to collect rewards from both goal zones alternately. Conduct daily training sessions (e.g., 15-30 minutes) for 3-7 days.

- Probe Trials: To test spatial learning independent of reward consumption, periodically conduct probe trials (e.g., 2-5 minutes) where the water reward solenoid is temporarily disabled. Measure the time the mouse's avatar spends in the previous reward zones.

- Data Analysis: Quantify learning using the metrics in Table 1 and Table 2, including the distance traveled between rewards, reward frequency, and dwell time in target zones during probe trials.

Protocol 2: Freely Moving Navigation with the Servoball System

This protocol outlines the use of the Servoball, a VR treadmill for freely moving rodents, integrated with a home-cage for high-throughput, operator-independent testing [1].

Application: Suitable for complex cognitive tasks requiring unrestricted movement, studying natural foraging behavior, and long-term automated behavioral phenotyping.

Materials: See Section 5.2 for details on required reagents and solutions.

Procedure:

- System Integration: Connect the Servoball arena to the animals' group home cage via an RFID-controlled tunnel access system. House rats in social groups.

- Animal Tagging: Implant all rats with unique RFID chips.

- Voluntary Access Training: Rats voluntarily leave the home cage and enter the Servoball arena through the RFID-controlled gate. This process is fully automated, allowing animals to self-schedule up to 10 training sessions per 24-hour period.

- Arena Operation: In the arena, a camera tracks the rat's position and movement on a large sphere. A closed-loop feedback control system uses this data to counter-rotate the sphere, keeping the rat near the apex. The VE is displayed on a 360° panorama of monitors.

- Task Training (Beacon/Landmark): Train rats to use visual or acoustic cues to locate a goal.

- Beacon Task: Place a distinct visual cue directly over the reward location.

- Landmark Task: Place visual cues around the arena that define the angular position of a hidden goal.

- Reward is delivered via retractable liquid reward devices at the arena periphery.

- Data Collection: The system automatically records trajectory data, choice accuracy, latency to goal, and movement kinematics. For neurophysiological experiments, combine with extracellular single-unit recordings from regions like the entorhinal cortex.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

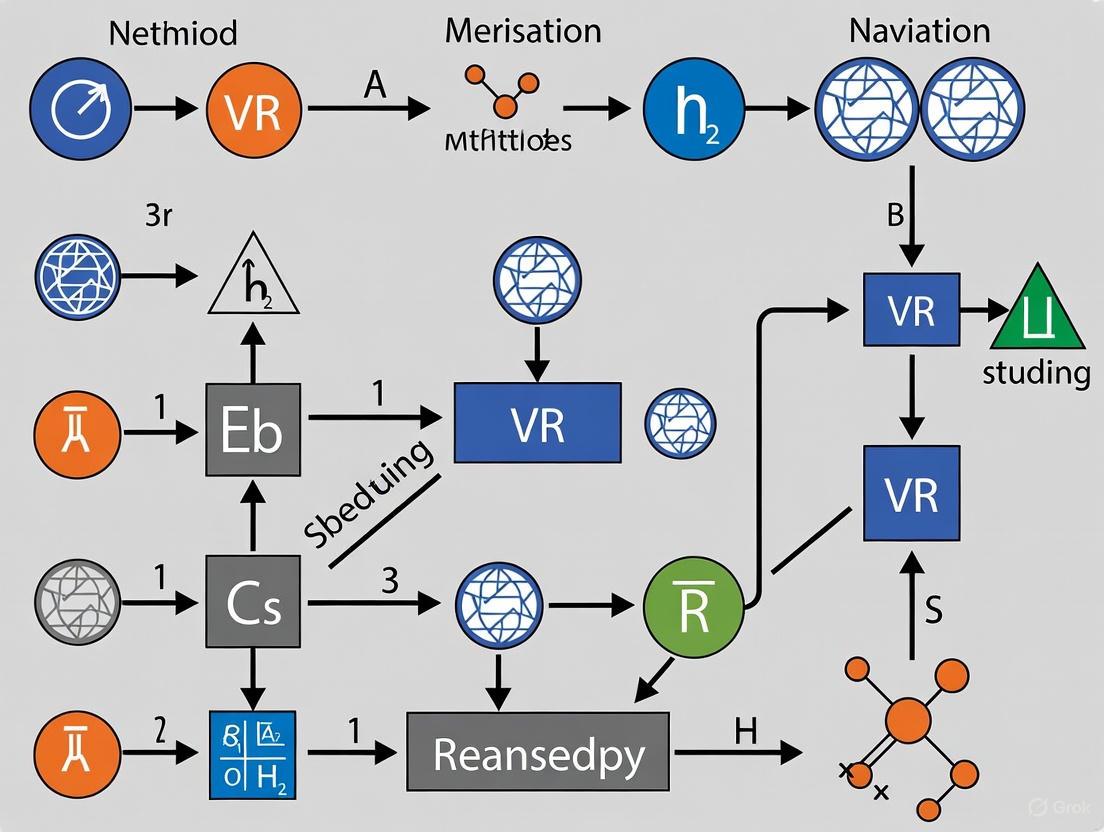

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical and operational workflows of closed-loop VR systems.

Diagram 1: Closed-Loop Feedback Logic in Rodent VR

Diagram 2: Servoball System Integration with Home Cage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Head-Fixed VR Systems

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Head-Fixed VR Protocols

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spherical Treadmill | Interface for rodent locomotion. | Air-levitated, low-friction sphere (e.g., 8-10 inch polystyrene ball) to ensure torque-neutral movement [2]. |

| Head-Fixation Apparatus | Secures animal's head for stable neural recording or imaging. | Custom-made or commercial stereotaxic frame compatible with the treadmill setup [2] [3]. |

| High-Speed Motion Sensor | Tracks ball rotation. | Optical or laser sensors that precisely measure X and Y rotation for closed-loop feedback [2]. |

| Visual Display | Presents the virtual environment. | Single or multiple LCD/LED monitors positioned to cover the rodent's field of view [2]. |

| Water Reward Solenoid | Delivers positive reinforcement. | Precision solenoid valve for controlled, micro-liter volume water delivery at goal locations [2] [3]. |

| VR Software Platform | Renders the environment and manages closed-loop logic. | Custom software (e.g., in Python, MATLAB) or game engine (e.g., Unity, Unreal) for real-time 3D rendering [2]. |

Essential Materials for Freely Moving Servoball Systems

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Freely Moving VR Protocols

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Servoball Treadmill | Spherical treadmill for free movement. | Large sphere (e.g., 600mm) on motorized rollers for active counter-rotation [1]. |

| RFID Tagging System | Automated animal identification and access control. | RFID chips implanted subcutaneously and readers at the home-cage access tunnel [1]. |

| High-Speed Camera | Tracks animal position on the ball. | 100 Hz camera for real-time tracking of body center and heading direction [1]. |

| Multi-Monitor Display | Creates an immersive 360° visual panorama. | Octagon of eight TFT monitors surrounding the arena to display the VR scene [1]. |

| Retractable Reward Devices | Delivers liquid or food reward. | Multiple devices placed at the arena periphery, activated when the animal reaches a virtual goal [1]. |

| Acoustic Stimulation System | Provides auditory spatial cues. | Multiple loudspeakers for presenting pure tones or other auditory gradients [1]. |

Virtual reality (VR) systems for rodents have emerged as a powerful experimental paradigm, particularly for the study of navigation behavior and its underlying neural mechanisms. By head-fixing a mouse or rat on a treadmill while it navigates a simulated environment, researchers gain unparalleled precision and control over sensory inputs and experimental variables [4]. This approach aligns closely with the 3Rs principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal research by enabling complex cognitive studies with reduced animal distress and improved experimental efficiency. This Application Note details the key advantages of VR systems, provides quantitative performance data, and outlines detailed protocols for implementing VR-based navigation studies, framing them within the context of a broader thesis on modern rodent research methodologies.

Key Advantages: Precision, Control, and Ethical Alignment

The adoption of VR in rodent neuroscience offers distinct advantages over traditional methods like physical mazes or freely moving paradigms.

Unmatched Experimental Control and Precision

- Stimulus Control: VR allows for exact manipulation of the visual environment, enabling the presentation of specific, repeatable, and complex sensory cues. Researchers can programmatically control every aspect of the visual scene, from the placement of landmarks to the statistics of evidence pulses in decision-making tasks [5].

- Head-Fixation Compatibility: Head-fixation is a cornerstone of modern systems neuroscience. It enables the use of high-precision neural recording techniques, such as two-photon calcium imaging and whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, which are challenging to perform in freely moving animals [4]. This allows for the direct observation of neural activity during complex behaviors.

Adherence to the 3Rs Ethical Framework

- Refinement: VR minimizes stressors associated with traditional methods. Experiments can be conducted in a controlled, stable environment, reducing animal anxiety. Notably, modern systems like "MouseGoggles" have been shown to elicit more naturalistic and innate behaviors, such as startle responses to looming stimuli, indicating a more positive welfare state compared to less immersive setups [6] [7].

- Reduction: The high data quality and experimental control afforded by VR can lead to a reduction in the number of animals required to achieve statistical power. The ability to collect vast datasets from a single animal over many trials increases the robustness of findings.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics in Rodent VR Systems

| System / Paradigm | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| MouseGoggles Duo [6] | Field of View (FOV) | ~140° vertical, 230° horizontal | Covers a large fraction of the mouse's natural visual field, enhancing immersion. |

| iMRSIV Goggles [8] | Field of View (FOV) | ~180° per eye | Provides near-total visual immersion, excluding external lab cues. |

| Evidence Accumulation Task [5] | Behavioral Performance | Mice sensitive to side differences of a single visual pulse | Demonstrates high perceptual acuity and cognitive capability in VR. |

| Treasure Hunt Task (AR vs. VR) [9] | Spatial Memory Accuracy | Significantly better in physical walking vs. stationary VR | Highlights a key limitation of stationary VR but also validates VR as a tool for studying core memory processes. |

| MouseGoggles & Place Cells [6] | Place Cell Recruitment | 19% of recorded CA1 cells | Similar to proportions found in real-world navigation, validating VR for spatial coding studies. |

Logistical and Technical Superiority

- Logistical Efficiency: VR paradigms eliminate the need for physical maze construction, storage, and cleaning between trials. Environments can be switched instantly, facilitating experimental designs with multiple contexts or rapid task prototyping [10] [11].

- Precise Behavioral Readouts: Systems can integrate detailed monitoring, such as pupillometry and eye tracking [6] or lick detection [10], providing rich, multimodal datasets that correlate neural activity with precise behavioral states.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Below are generalized protocols for setting up and conducting a VR-based navigation experiment, synthesizing common elements from the literature.

Protocol 1: Assembly of a Rodent VR System

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a basic VR rig for head-fixed navigation.

- Objective: To build a VR system capable of presenting immersive visual environments to a head-fixed rodent navigating a spherical treadmill.

- Materials:

- Spherical treadmill (e.g., Styrofoam ball)

- Air supply system to float the ball

- Optical sensors (e.g., optical mouse sensors) to track ball rotation

- Visual display system (see options below)

- Head-fixing apparatus

- Reward delivery system (e.g., lick port with solenoid valve)

- Control computer with software (e.g., Unity, Unreal Engine, or custom solutions like behaviorMate [11])

- Procedure:

- Set up the Treadmill: Position the spherical treadmill within a stable frame. Connect the air supply to create a consistent air cushion that allows the ball to rotate with minimal friction.

- Install Motion Tracking: Mount optical sensors around the treadmill to capture the X and Y rotation of the ball. Calibrate the sensor output to translate ball movement into virtual displacement.

- Configure the Display: Choose and position the visual display.

- Integrate Reward System: Place a reward delivery port (e.g., for water) within easy reach of the animal's mouth. Connect it to a solenoid valve controlled by the software.

- Software Integration: Implement closed-loop control in the experiment software. The software must:

- Continuously read data from the motion sensors.

- Update the virtual environment's viewpoint in real-time based on the animal's movement.

- Control task logic (e.g., cue presentation, reward delivery upon reaching a goal).

Diagram 1: VR System Closed-Loop Workflow. This diagram illustrates the real-time data flow that creates a closed-loop interaction between the rodent's behavior and the virtual environment.

Protocol 2: Virtual T-Maze Evidence Accumulation Task

This protocol adapts the task described in [5] for studying perceptual decision-making.

- Objective: To train a mouse to navigate a virtual T-maze and choose an arm based on accumulated visual evidence.

- Materials:

- Functional VR system (as in Protocol 1).

- Custom software script for a T-maze environment with pulsing visual cues (e.g., towers).

- Pre-Training:

- Habituation: Acclimate the mouse to head-fixation and running on the treadmill. Allow it to freely explore a simple virtual corridor.

- Shape Task Understanding: Initially, place a single, persistent visual cue at the correct choice arm. Reward the mouse for entering that arm.

- Introduce Evidence Pulses: Gradually transition to the full task: as the mouse runs down the stem of the T-maze, present brief, flashing visual cues (pulses) on the left and right sides. The side with the greater number of pulses indicates the rewarded arm.

- Task Execution:

- Trial Start: The mouse is virtually placed at the start of the T-maze stem.

- Cue Period: As it runs, it receives

Npulses of evidence on one side andMpulses on the other, generated randomly per trial (e.g., via Poisson statistics). - Choice Point: The mouse reaches the T-junction and must turn left or right.

- Outcome:

- Correct Choice: A reward is delivered (e.g., a drop of water).

- Incorrect Choice: A time-out period occurs, often accompanied by a negative cue like a white noise sound.

- Inter-Trial Interval: A short pause before the next trial begins.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Hardware for VR Navigation Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| VR Display Systems | MouseGoggles [6], iMRSIV Goggles [8], Panoramic Monitors [4], DomeVR [12] | Presents the controlled visual environment to the subject. Goggles offer higher immersion and are compatible with overhead microscopy. |

| Motion Tracking | Optical mouse sensors, Rotary encoders [11], Ball tracking cameras | Precisely measures the animal's locomotion on the treadmill to update the virtual world in closed-loop. |

| Behavioral Control Software | behaviorMate [11], DomeVR (Unreal Engine) [12], Godot Engine [6] | Orchestrates the experiment: controls stimuli, records behavior, triggers rewards, and synchronizes with neural data acquisition. |

| Modular Maze Hardware | Adapt-A-Maze (AAM) track pieces and reward wells [10] | Provides physical, automated components for non-VR or augmented reality (AR) setups, enabling flexible behavioral paradigms. |

| Neural Recording Compatibility | Two-photon microscopes, Electrophysiology rigs, Implanted electrodes [9] [6] | Allows for simultaneous measurement of neural activity (e.g., from hippocampus or visual cortex) during VR behavior. |

Diagram 2: T-Maze Evidence Accumulation Logic. The workflow for a single trial in a decision-making task, where mice integrate multiple visual cues to make a choice [5].

Virtual reality systems represent a significant advancement in the toolkit for studying rodent navigation behavior. They provide a unique combination of unprecedented experimental control, compatibility with cutting-edge neural recording techniques, and a strong ethical alignment with the 3Rs principle. The quantitative data and detailed protocols provided herein serve as a foundation for researchers in neuroscience and drug development to adopt and leverage these powerful methods. As VR technology continues to evolve—with trends pointing towards even greater immersion, miniaturization, and multi-sensory integration—its value in unraveling the complexities of the brain and behavior will only increase.

The study of rodent navigation behavior has been revolutionized by the continuous evolution of experimental tools. The journey from early treadmill systems, which constrained movement to study basic locomotion and fatigue, to modern immersive virtual reality (VR) environments represents a significant paradigm shift in neuroscience and behavioral research. This progression has been driven by the need for greater experimental control, higher throughput, and more naturalistic settings that allow for the investigation of complex cognitive processes like spatial navigation and memory. The integration of advanced computer vision, machine learning, and high-performance graphics has enabled the development of systems that adapt to the animal's behavior in real-time, providing a powerful framework for studying the neurophysiology underlying behavior. This article traces this technological evolution, detailing the key innovations and providing practical experimental protocols for contemporary systems.

From Simple Locomotion to Controlled Fatigue Assays

Early treadmill systems were fundamental tools for investigating basic locomotor behavior and physiological capacity in rodents. These systems primarily consisted of a moving belt that forced the animal to walk or run, often with aversive stimuli like mild electric shock grids or air puffs to motivate movement.

The Treadmill Fatigue Test was developed as a simple, high-throughput assay to measure fatigue-like behavior, distinct from tests of maximal endurance [13]. In this protocol, fatigue is operationalized as a decreased motivation to avoid a mild aversive stimulus, rather than physiological exhaustion. The key quantitative data from such assays is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for the Treadmill Fatigue Test [13]

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Description and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Treadmill Inclination | 10° | Consistent angle for training and testing; increases workload. |

| Electric Shock | 2 Hz, 1.22 mA | Pulsatile (200 msec) motivator; should produce only a mild tingling sensation. |

| Fatigue Zone | ~1 body length at rear | The criterion for test completion is 5 continuous seconds in this zone. |

| Training Speeds | 8 m/min to 12 m/min | Speed is gradually increased over 2 days of training. |

| Test Duration | Up to 15 minutes | Standardized duration for assessing fatigue-like behavior. |

The experimental workflow for this foundational protocol is outlined below.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for the classic Treadmill Fatigue Test, highlighting the multi-day training and standardized testing endpoint [13].

While these traditional treadmills provided valuable data, their limitations were clear: they enforced preset speeds and directions, severely restricting the investigation of natural, volitional movement and navigation.

The Advent of Adaptive and Omnidirectional Systems

A significant leap forward came with the development of treadmills that could adapt to the animal's behavior. The Spherical Treadmill replaced the linear belt with an air-supported foam ball, allowing a head-fixed mouse to run freely in any direction while enabling precise real-time data capture [14]. This system was a cornerstone for integrating virtual reality, as its real-time X and Y speed outputs (0-5V analog signals) could be used to control a virtual environment [14].

Concurrently, real-time vision-based adaptive treadmills emerged, using computer vision to solve the limitation of preset speeds. These systems track the animal's position using either marker-based (colored blocks, AprilTags) or marker-free methods (a pre-trained FOMO MobileNetV2 network) and dynamically adjust the belt speed and direction via a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control algorithm to keep the animal centered [15]. The control principle is defined by the equation:

uadjust(t) = Kp · Δx + Ki · ∫Δx dt + Kd · d(Δx)/dt [15]

Where the adjustment amount u_adjust is a function of the positional error (Δx) and its integral and derivative, multiplied by their respective gains.

For larger animals and human research, Omnidirectional Treadmills (ODTs) like the Infinadeck were developed. These platforms, often using a belt-in-belt design, allow users to walk in any direction, thus solving the "VR locomotion problem"—the sensory mismatch from navigating a large virtual space within a confined physical one [16]. Kinematic studies show that while ODT walking resembles natural gait, it is characterized by slower speeds and shorter step lengths, likely due to the novelty of the environment and user caution [16].

The Shift to Immersive Virtual Reality Environments

The integration of VR with adaptive treadmills marked the beginning of a new era, creating controlled yet naturalistic settings for studying navigation. Early systems coupled self-paced treadmills with virtual environments projected onto large screens, where the scene progression and platform motion were synchronized with the subject's walking speed [17].

The drive for greater immersion has led to two dominant modern approaches: headset-based and projection-based VR.

Headset-Based Immersion: MouseGoggles

The MouseGoggles system represents a miniaturization breakthrough. Inspired by human VR, it is a head-mounted display for mice that uses micro-displays and Fresnel lenses to provide a wide field of view (up to 230° horizontal) with independent, binocular visual stimulation [6]. Its key advantage is blocking out conflicting real-world stimuli, thereby enhancing immersion. This is validated by the elicitation of innate startle responses to looming stimuli in naive mice—a behavior not observed in traditional projector-based systems [6]. Advanced versions like MouseGoggles EyeTrack have embedded infrared cameras for simultaneous eye tracking and pupillometry during VR navigation [6].

Projection-Based Immersion: DomeVR

As an alternative, DomeVR provides immersion via a projection dome. Built using the Unreal Engine 4 (UE4) game engine, it leverages photo-realistic graphics and a user-friendly visual scripting language to create complex, naturalistic environments for various species, including rodents and primates [12]. The system includes crucial features for neuroscience, such as timing synchronization for neural data alignment and an experimenter GUI for adjusting task parameters in real-time [12].

The logical relationship between user input, the VR system, and the resulting scientific output is illustrated below.

Figure 2: Signaling and data flow in a modern rodent VR navigation paradigm. Locomotion is used to navigate VR environments, generating rich, multimodal data for analysis [14] [6] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Modern immersive VR research relies on a suite of specialized hardware and software components. The following table details essential "research reagents" for setting up a state-of-the-art rodent VR navigation laboratory.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Rodent VR Navigation

| Item Name | Type | Key Function & Features | Representative Example / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical Treadmill | Core Locomotion Interface | Air-supported ball; allows free 2D movement; provides X/Y analog speed data for VR control. | Labeotech Spherical Treadmill [14] |

| Head-Mounted VR Display | Visual Stimulation | Miniature display for immersive, binocular stimulation; blocks external light. | MouseGoggles [6] |

| Game Engine | Software Environment | Creates and renders complex, realistic 3D environments; enables visual scripting. | Unreal Engine 4 (DomeVR) [12] |

| Machine Vision System | Tracking & Control | Enables marker-free animal tracking for adaptive treadmill control via deep learning. | OpenMV with FOMO MobileNetV2 [15] |

| Integrated Eye Tracker | Physiological Monitoring | Tracks pupil diameter and gaze position within the VR headset during behavior. | MouseGoggles EyeTrack [6] |

| Modular Behavioral Maze | Complementary Tool | Open-source, automated maze system for flexible behavioral testing outside VR. | Adapt-A-Maze (AAM) [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Spatial Learning in a VR Linear Track

The following protocol describes a standard procedure for training head-fixed mice on a spatial learning task using an immersive VR system, integrating elements from the reviewed technologies.

Application Note: This protocol is designed to study hippocampal-dependent spatial memory and place cell activity in head-fixed mice. It is ideally suited for experiments combining behavior with electrophysiology or optical imaging.

Materials and Equipment:

- VR System: A headset-based (e.g., MouseGoggles Duo) or projection-based VR setup.

- Locomotion Interface: A spherical treadmill or a low-profile linear treadmill.

- Data Acquisition System: Hardware/software for recording neural data (e.g., extracellular amplifiers, two-photon microscopes).

- Reward Delivery System: A solenoid-controlled liquid delivery system linked to a lick port.

Procedure:

System Setup and Calibration:

- Virtual Environment: Build a linear track environment (e.g., ~1.5-2 meters in virtual length) with distinct visual cues along the walls in your game engine (e.g., Unreal Engine, Godot). Define a "reward zone" (e.g., 20 cm long) at a fixed location on the track.

- Synchronization: Ensure the VR system sends a TTL pulse at the start of each trial and records a continuous timestamped log of the animal's virtual position, lick events, and reward deliveries.

- Treadmill Calibration: Calibrate the treadmill's motion sensors so that the animal's locomotion accurately controls its movement through the virtual linear track.

Animal Habituation (Days 1-2):

- Head-fix the mouse on the treadmill and allow it to habituate to the setup for 20-30 minutes per day.

- Initially, let the mouse explore the virtual track without any task requirements. Deliver occasional free rewards at the reward zone to associate the location with a positive outcome.

Behavioral Training (Days 3-7):

- Initiate the learning paradigm. A trial consists of the mouse running from the start of the track to the end.

- Reward Contingency: Deliver a small liquid reward (e.g., ~5-10 µL) only when the mouse licks the reward port within the designated reward zone.

- Probe Trials: On days 4-5, intersperse standard trials with unrewarded "probe" trials to assess the mouse's anticipatory licking behavior at the reward zone without the confound of reward consumption.

- Conduct 1-2 training sessions per day, each consisting of 20-40 trials or lasting until the mouse achieves a set number of rewards (e.g., 50-100).

Data Analysis:

- Behavioral Analysis: Calculate the lick preference ratio (licks in reward zone / total licks) during probe trials. Successful learning is indicated by a significant increase in anticipatory licking in the reward zone over training days [6].

- Neural Analysis: For neural recordings, sort spikes and correlate firing with the animal's virtual position. Place cells will exhibit increased firing rates in specific locations ("place fields") along the virtual track [6].

The historical progression from simple treadmills to modern immersive VR environments illustrates a relentless pursuit of more refined tools for deconstructing the complexities of brain and behavior. This evolution has transformed our experimental capabilities, moving from observing forced locomotion to studying volitional navigation in precisely controlled, yet richly naturalistic, worlds. Current state-of-the-art systems combine adaptive treadmills, immersive visual stimulation via headsets or domes, and integrated physiological monitoring, providing neuroscientists with an unprecedented toolkit. These technologies continue to bridge the critical gap between highly controlled laboratory settings and the naturalistic behaviors they aim to model, powerfully enabling new discoveries in spatial navigation, memory, and decision-making.

Virtual reality (VR) systems have become an indispensable tool in behavioral and systems neuroscience, particularly for studying the neural mechanisms underlying rodent spatial navigation [4]. These systems create simulated environments that allow experimenters to maintain precise control over sensory inputs while enabling complex, naturalistic behaviors. Crucially, VR facilitates stable neural recording via techniques such as electrophysiology and two-photon calcium imaging in head-fixed animals, permitting investigation of neural circuits during defined navigational tasks [6] [4]. The core components of any rodent VR setup—tracking systems, visual displays, and computational architecture—work in concert to close the loop between an animal's self-motion and its sensory experience, creating a compellingly immersive environment for studying behavior and brain function.

Core Component 1: Animal Movement Tracking

The accurate, real-time measurement of an animal's movement is the foundational input for any closed-loop VR system. This tracking data is used to update the virtual environment in real time, maintaining the correspondence between action and perception essential for naturalistic behavior.

Primary Tracking Modalities

| Tracking Modality | Description | Key Components | Typical Data Output | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical Treadmill [4] | A low-friction spherical ball floating on an air cushion. The animal's locomotion rotates the ball. | Styrofoam/polystyrene ball, air compressor/supply, motion sensors (e.g., optical encoders). | Angular velocity (pitch, yaw), linear displacement (calculated). | High-quality air supply needed for low friction; ball mass must suit animal size. |

| Optical Encoders [4] | Sensors that measure the rotation of the spherical treadmill. | Rotary encoders, microcontroller. | X, Y rotation values (or equivalent voltage signals). | Provides high-temporal-resolution data on ball rotation. |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Sensors placed on the animal's head or body to measure acceleration and orientation. | Accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer. | Acceleration, angular velocity, head orientation. | Can be used in freely moving setups; provides complementary head-movement data. |

Integrated Tracking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard data flow for tracking animal movement in a spherical treadmill-based VR system.

Core Component 2: Visual Display Systems

The visual display is the primary output channel for presenting the virtual world to the rodent. Recent advances have moved beyond traditional projector-based panoramic screens to miniaturized, head-mounted displays, offering greater immersion and integration with other hardware.

Quantitative Comparison of Display Technologies

| Display Technology | Field of View (FOV) | Angular Resolution | Spatial Acuity | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) [6] | 230° horizontal, 140° vertical per eye | ~1.57 pixels/degree | Nyquist freq.: ~0.78 c.p.d. | MouseGoggles |

| Panoramic Projector/Screen [4] | Up to 360° (varies) | Varies with projector/screen distance | Limited by screen resolution & distance | Traditional Dome/Spherical Screen |

| Head-Mounted Display (HMD) with Eye Tracking [6] | 230° horizontal, 140° vertical per eye | ~1.57 pixels/degree | Nyquist freq.: ~0.78 c.p.d. | MouseGoggles EyeTrack |

Visual Stimulus Generation and Rendering Workflow

Creating and displaying a virtual environment involves a structured pipeline from scene creation to final image presentation on the rodent's display.

Core Component 3: Computational Architecture

The computational backbone of a VR system integrates tracking input and visual output, manages experimental logic, and ensures precise timing for synchronizing behavior with neural data.

System Specifications and Performance Metrics

| Computational Element | Hardware/Software Examples | Key Function | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Processing Unit [6] [12] | Raspberry Pi 4, Desktop PC | Runs game engine, executes task logic, renders graphics. | Rendering: 80 fps; Input-to-display latency: <130 ms [6]. |

| Game Engine & Framework [6] [12] | Godot Engine, Unreal Engine (UE4) | Creates 3D environments, implements experimental paradigms. | Frame-by-frame synchronization, visual scripting for task flow. |

| Synchronization & Logging [12] | Custom UE4 plugins (DomeVR), SpikeGadgets ECU | Records behavioral data, generates event markers for neural data alignment. | Resolves timing uncertainties, enables offline analysis. |

| Input/Output (I/O) Control [10] [12] | Arduino, SpikeGadgets ECU, Pyboard | Interfaces with reward delivery, lick detectors, barriers; receives eye-tracking data. | TTL pulse control for automation; precise reward delivery. |

Integrated System Data Flow and Control

The following diagram illustrates how the three core components interact within a complete, closed-loop rodent VR system.

Experimental Protocol: Spatial Navigation Learning in Linear Track VR

This protocol details a standard procedure for training rodents on a spatial navigation task in a virtual linear track, adapted from methodologies used with systems like MouseGoggles and DomeVR [6] [12].

Materials and Setup

- VR System: Configured with a linear track virtual environment. The track should have distinct visual cues along its length and a defined reward zone.

- Reward System: Liquid reward (e.g., sweetened water or milk) delivered via a solenoid valve connected to a lick port. The port should have an integrated infrared beam break for lick detection [10].

- Spherical Treadmill: Properly calibrated and floating on a stable air stream.

- Data Acquisition System: To record behavioral data (position, licks, rewards) and synchronize with neural data if applicable.

Procedure

- Habituation (Day 1): Place the head-fixed mouse on the treadmill in the VR setup. Allow it to freely explore the linear track for 20-30 minutes without any reward contingencies to acclimate to the environment.

- Initial Training (Days 2-3): Begin the standard reward protocol. Deliver a small liquid reward (e.g., ~5 µL) automatically when the mouse enters the designated reward zone. This teaches the animal to associate the virtual location with reward.

- Lick-Contingent Reward (Days 3-5): Introduce a behavioral requirement. The reward is only delivered if the mouse licks the reward port upon entering and remaining within the reward zone. This encourages anticipatory licking as a behavioral readout of spatial learning [10].

- Probe Trials (Day 4-5): Intersperse unrewarded trials to assess learning. An increase in anticipatory licking specifically in the reward zone, compared to a control zone, indicates successful spatial learning [6].

Data Analysis

- Performance Metrics: Calculate the lick preference index for the reward zone versus a control zone during probe trials.

- Spatial Tuning: If neural data is collected, analyze the formation and stability of place cells (hippocampal neurons that fire at specific locations) across sessions [6].

- Behavioral Scoring: Use tools like DeepLabCut and Keypoint-MoSeq for detailed, unsupervised analysis of full-body behavioral motifs (syllables) triggered by navigation or stimuli [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table catalogs the key hardware and software solutions used in modern rodent VR setups for navigation research.

| Item Name | Type | Function in VR Research |

|---|---|---|

| MouseGoggles [6] | Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Miniature VR headset for mice providing wide-field, binocular visual stimulation and enabling integrated eye tracking. |

| Adapt-A-Maze (AAM) [10] | Modular Hardware | Open-source, automated maze system using modular track pieces to create flexible physical environments for behavioral tasks. |

| Spherical Treadmill [4] | Tracking Apparatus | A low-friction floating ball that transduces the animal's locomotion into movement signals for the VR system. |

| Godot Engine [6] | Software | Video game engine used to design 3D virtual environments, program experimental paradigms, and handle low-latency I/O communication. |

| Unreal Engine (UE4) with DomeVR [12] | Software Framework | A high-fidelity game engine with a custom toolbox (DomeVR) for creating immersive, timing-precise behavioral tasks for multiple species. |

| DeepLabCut [18] | Analysis Software | Open-source tool for markerless pose estimation of animals, enabling detailed analysis of body language and behavior during VR tasks. |

| Keypoint-MoSeq [18] | Analysis Software | Computational tool that uses pose estimation data to identify recurring, sub-second behavioral motifs ("syllables") in an unsupervised manner. |

A Practical Guide to Modern VR Systems and Their Research Applications

Virtual reality (VR) has become an indispensable tool in neuroscience for studying the neural mechanisms of rodent navigation and spatial memory. By offering precise control over the sensory environment, VR enables researchers to perform neurophysiological recordings that would be challenging in real-world settings. The two predominant hardware paradigms for delivering VR to head-fixed rodents are head-mounted displays (HMDs), exemplified by the MouseGoggles system, and projection arenas, such as the DomeVR environment.

This application note provides a detailed technical comparison of these approaches, including structured quantitative data, standardized experimental protocols, and essential reagent solutions, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate technology for rodent navigation studies.

Technology Comparison: Specifications and Performance

The choice between HMDs and projection arenas involves significant trade-offs in immersion, field of view, integration with recording equipment, and implementation complexity. The table below summarizes the key technical specifications and performance characteristics of the two systems.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of HMD and Projection Arena Systems

| Feature | Head-Mounted Display (MouseGoggles) | Projection Arena (DomeVR) |

|---|---|---|

| System Type | Miniature headset with displays and lenses [6] | Dome or panoramic projection screen [12] |

| Visual Field Coverage | ~230° horizontal, ~140° vertical per eye [6] | Typically full 360° panoramic [12] |

| Binocular Capability | Yes, independent control per eye [6] | Yes (dependent on projection setup) |

| Native Angular Resolution | ~1.57 pixels/degree [6] | Varies with projector resolution and dome size |

| Typical Display Latency | <130 ms [6] | Dependent on game engine and projector; requires synchronization solutions [12] |

| Typical Frame Rate | 80 fps [6] | Dependent on game engine and graphics complexity [12] |

| Integrated Eye Tracking | Yes (Infrared cameras in eyepieces) [6] | Possible, but typically an external add-on [12] |

| Inherent Immersion Level | High (blocks external lab cues) [6] [19] | Moderate (lab environment may be partially visible) |

| Overhead Stimulation | Excellent (headset pitch can be adjusted) [6] | Difficult (hardware often obstructs the top) [19] |

| Key Hardware Components | Smartwatch displays, Fresnel lenses, Raspberry Pi, 3D-printed parts [6] [20] | Digital projector, spherical dome, gaming computer, mirror[s [12]] |

| Relative Cost | Low (~$200 for parts) [21] | High (commercial projectors and custom domes) |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate (requires assembly and optical alignment) [22] | High (requires geometric calibration of projection) [12] |

| Mobility for Subject | Designed for head-fixed subjects; mobile versions in development [20] | Primarily for head-fixed subjects [12] |

| Best Suited For | Experiments requiring high immersion, overhead threats, eye tracking, or a compact footprint [6] [19] | Large-field panoramic stimulation, multi-species applications, and highly complex 3D environments [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Rodent Navigation

Protocol 1: Virtual Linear Track Place Learning

This protocol is used to study spatial memory and learning by training mice to associate a specific virtual location with a reward [6].

Application: Assessing hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory formation. Primary Systems: MouseGoggles Duo [6] or DomeVR [12].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Head-fix the mouse on a spherical or linear treadmill positioned in front of the VR system.

- Habituation: Allow the mouse to explore a simple virtual linear track for 1-2 sessions without rewards to acclimate to the VR environment and treadmill operation.

- Training (Days 1-3): Display the virtual linear track. When the mouse navigates the avatar to a pre-defined reward zone, automatically deliver a small liquid reward (e.g., ~5 µL sucrose water). Each training session typically lasts 20-60 minutes [6].

- Probe Trial (Days 4-5): Conduct an unrewarded session with the reward system disabled. Measure the animal's anticipatory licking behavior as a proxy for spatial expectation.

- Data Acquisition:

- Behavioral Data: Log the avatar's position, velocity, and timing of all licks.

- Neural Data (Optional): Simultaneously perform calcium imaging (e.g., of hippocampal CA1 neurons) or electrophysiology.

- Analysis: Calculate a lick probability map by binning the track and dividing the number of licks in each bin by the time spent in that bin. Compare the lick probability in the reward zone versus a control zone. Statistically significant increase in reward-zone licking indicates successful spatial learning [6].

Protocol 2: Innate Looming Response Test

This protocol leverages the mouse's innate defensive behavior to an overhead threat to quantify the immersiveness of the VR system [6] [19].

Application: Validating the ecological validity and immersiveness of a VR setup; studying innate fear circuits. Primary System: MouseGoggles (due to superior overhead stimulation capability) [6] [19].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Use a naive mouse with no prior VR experience. Head-fix it on a treadmill.

- Baseline Recording: Allow the mouse to freely explore a neutral virtual environment (e.g., a gray arena) for 60 seconds to establish a behavioral and pupillometry baseline.

- Stimulus Presentation: Suddenly present a looming stimulus. This is typically a dark, expanding disk that reaches its maximum size (e.g., covering 30-50° of the visual field) within 0.5-1 second, simulating a diving predator. The stimulus should be presented in the upper visual field [19].

- Post-Stimulus Recording: Continue recording for at least 60 seconds after the stimulus vanishes to observe the recovery of behavior and pupil size.

- Data Acquisition:

- Behavioral Scoring: Manually or automatically score the presence of a "startle response" (a rapid jump, kick, or freezing) upon the first presentation [6].

- Locomotion: Track the mouse's running velocity. A sharp slowdown or reversal is a common defensive behavior [6].

- Pupillometry: Record pupil diameter using integrated eye-tracking cameras (e.g., MouseGoggles EyeTrack) as a metric of arousal [6].

- Analysis:

- Quantify the percentage of mice that exhibit a startle response on the first trial.

- Plot the average running velocity and pupil diameter aligned to the loom onset. Compare these metrics to the baseline period using statistical tests (e.g., t-test).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of rodent VR experiments requires both hardware and software components. The following table details the key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Rodent VR

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spherical Treadmill | Allows head-fixed animal to navigate the virtual environment through locomotion [6] [2]. | Often a lightweight Styrofoam or acrylic ball, levitated by air [2]. |

| Optical Sensors | Tracks the rotation of the spherical treadmill to update the virtual world [22]. | Typically USB optical mouse sensors. |

| Microcontroller | Acquires data from sensors and communicates movement to the rendering computer [22]. | Arduino or Teensy, often emulating a computer mouse for universal compatibility [22]. |

| Rendering Computer | Generates the virtual environment in real-time. | HMD: Raspberry Pi 4 [6] [22]. Projection: Gaming PC [12]. |

| Game Engine Software | Platform for designing 3D environments and programming experimental logic. | HMD: Godot Engine [6] [22]. Projection: Unreal Engine 4 (UE4) [12] [23]. |

| Circular Micro-Displays | Visual output for the head-mounted display. | ~1.1-inch circular LCDs, repurposed from smartwatches [6] [20]. |

| Fresnel Lenses | Positioned in front of displays to provide a wide field of view and set the focal distance to near-infinity for the mouse [6]. | Custom short-focal length lenses. |

| Infrared (IR) Cameras | Integrated into the HMD for eye and pupil tracking (pupillometry) [6]. | Miniature board cameras with IR filters. |

| Hot Mirror | Used in HMD with eye tracking to reflect IR light from the eye to the camera while allowing visible light from the display to pass through [6]. | |

| Two-Photon Microscope | For functional imaging of neural activity (e.g., using GCaMP) during VR behavior [6]. | The HMD's compact size reduces stray light contamination during imaging [6]. |

| Electrophysiology System | For recording single-unit or local field potential activity from deep brain structures like the hippocampus during navigation [6]. | e.g., silicon probes or tetrodes. |

System Architecture and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core components and data flow in a typical integrated rodent VR setup for neuroscience research.

System Architecture Diagram:

The study of rodent navigation behavior is a cornerstone of behavioral neuroscience, providing critical insights into spatial learning, memory, and cognitive processes. Traditional physical mazes have inherent limitations in flexibility, experimental control, and logistical requirements. Virtual Reality (VR) methods, powered by advanced game engines like Unreal Engine, present a transformative alternative. These technologies enable the creation of highly controlled, complex, and adaptable virtual environments for rigorous behavioral research. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for leveraging Unreal Engine to develop realistic virtual environments for rodent navigation studies, framed within a comprehensive research thesis.

The Rationale for Game Engines in Behavioral Neuroscience

Modern game engines are uniquely suited to overcome the challenges of physical experimental paradigms. Unreal Engine is specifically engineered for demanding applications, featuring a highly optimized graphics pipeline that delivers photorealistic visuals at the high frame rates required for believable VR experiences [24]. Its robust Extended Reality (XR) framework, with support for the open OpenXR standard, ensures compatibility with a wide ecosystem of VR hardware [24].

Crucially, the validity of VR-generated data is supported by empirical evidence. A 2024 quantitative comparison of virtual and physical experiments in human studies concluded that VR "can produce similarly valid data as physical experiments when investigating human behaviour," with participants reporting almost identical psychological responses [25]. This foundational validation provides confidence for its application in preclinical behavioral research, enabling the investigation of complex scenarios in a safe, fully controlled, and repeatable environment [25].

Unreal Engine Workflow: From Concept to Virtual Maze

Creating a virtual environment for research is a structured process that moves from a clear objective to a polished, effective experimental tool. The workflow can be broken down into four key phases.

Core Development Workflow

The table below outlines the high-level stages of the VR content creation process for a research environment.

Table 1: Core Stages of the VR Content Creation Workflow for Research

| Stage | Key Activities | Research Output |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-production | Define hypotheses; Storyboard rodent tasks; Select VR hardware (standalone vs. PC-tethered). | Experimental design document; Approved animal use protocol. |

| Asset Generation | Create 3D models of maze elements (walls, rewards, cues) using AI-assisted tools or traditional modeling. | A library of optimized, reusable 3D assets for behavioral experiments. |

| Engine Integration | Assemble the scene in Unreal Engine; program interactivity and trial logic using Blueprint visual scripting or C++; integrate with data acquisition systems. | A functional virtual environment ready for validation testing. |

| Testing & Optimization | Conduct pilot trials; Ensure stable frame rates; Validate behavioral measures against positive and negative controls. | A validated and reliable virtual maze protocol for data collection. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the core development workflow for creating a virtual experimental environment.

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Navigation Studies

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing a virtual rodent navigation task, inspired by next-generation physical systems like the Adapt-A-Maze (AAM) [10].

Protocol: Automated Spatial Navigation Task in a Modular Virtual Maze

1. Objective: To assess spatial learning and memory in rodents by requiring them to navigate a customizable virtual maze to locate a fluid reward.

2. Pre-experimental Setup:

- Hardware: Prepare a VR setup with a head-mounted display (HMD) suitable for rodents, a spherical treadmill for locomotion, and a reward delivery system.

- Software: Assemble the virtual maze in Unreal Engine using modular track pieces (straight, T-junction, 90-degree turn). Program the environment to respond to the rodent's locomotion on the treadmill.

- Habituation: Acclimate the rodent to the experimenter, head-restraint (if used), and the VR environment over 3-5 sessions.

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Trial Initiation: The rodent is placed on the treadmill, initiating the VR experience. The virtual maze is rendered in the HMD.

- Navigation: The rodent navigates the maze by moving on the treadmill. Its virtual path is tracked in the Unreal Engine environment.

- Reward Delivery: Upon reaching the designated virtual reward well (a specific location in the maze), a lick is detected at a physical reward spout, triggering the delivery of a liquid reward [10].

- Inter-trial Interval: A period of 10-20 seconds is enforced between trials.

- Session Structure: Conduct one session per day, consisting of 20 trials, for 10-15 consecutive days.

4. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Primary Metrics: Escape latency (time to reward), total path length, and number of errors (wrong turns) are recorded automatically by the Unreal Engine application.

- Advanced Analysis: Adapt the Green Learning (GL) framework for behavioral classification. Segment the trajectory into sub-paths and use Discriminant Feature Test (DFT) and Subspace Learning Machines (SLM) to classify navigation strategies (e.g., direct path, thigmotaxis, scanning) [26].

Quantitative Comparison of Experimental Paradigms

The choice between physical and virtual paradigms involves several considerations. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison based on available data.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Physical and Virtual Reality Experimental Paradigms

| Parameter | Physical Reality (PR) | Virtual Reality (VR) with Unreal Engine | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Control | Limited; subject to audio, light, and odor fluctuations. | Complete and precise control over all sensory cues. | Enhanced experimental rigor and reduced confounding variables [25]. |

| Scenario Repeatability | Low; difficult to replicate exact conditions for all subjects. | Perfectly repeatable environment for every subject and trial. | Improved reliability and replicability of findings [25]. |

| Ethical Viability | Lower for high-risk scenarios (e.g., predator threats). | High; enables study of high-risk contexts safely. | Expands the scope of ethically permissible research questions [25]. |

| Logistical & Financial Cost | High for complex, custom mazes; storage is an issue [10]. | High initial development cost; lower long-term cost for adaptation and scaling. | Modular virtual mazes offer superior long-term flexibility and cost-efficiency [10]. |

| Data Validity | The traditional benchmark. | Shows "almost identical psychological responses" and "minimal differences in movement" in human studies, supporting its validity [25]. | VR is a valid data-generating paradigm for behavioral research [25]. |

System Architecture and Data Flow

A virtual navigation experiment requires the integration of multiple hardware and software components. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of information and control within the system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of a VR-based rodent navigation lab requires both hardware and software "reagents." The following table details key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for VR Rodent Navigation

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Unreal Engine | The core game engine software used to create, render, and manage the interactive virtual environment. | Free for use; source code access; supports Blueprint visual scripting and C++ [24]. |

| Modular Maze Assets | Reusable 3D models that form the building blocks of the virtual environment. | Inspired by the Adapt-A-Maze system: straight tracks, T-junctions, reward wells [10]. |

| VR Head-Mounted Display (HMD) | Displays the virtual environment to the rodent. | Custom-built for rodent models, providing wide-field visual stimulation. |

| Spherical Treadmill | Translates the rodent's natural locomotion into movement through the virtual environment. | A lightweight, low-friction air-supported ball. |

| Automated Reward System | Precisely delivers liquid reward upon successful task completion. | Incorporates a lick detection circuit (e.g., infrared beam break) and a solenoid valve for reward delivery [10]. |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Records behavioral data and synchronizes it with neural data. | Systems from SpikeGadgets, Open Ephys, or National Instruments that accept TTL signals [10]. |

| Green Learning (GL) Framework | An interpretable, energy-efficient machine learning framework for classifying rodent navigation strategies from trajectory data. | Comprises Discriminant Feature Test (DFT) and Subspace Learning Machines (SLM) [26]. |

The study of spatial navigation and memory represents a cornerstone of behavioral neuroscience, providing critical insights into fundamental cognitive processes and their underlying neural mechanisms. Virtual reality (VR) technology has emerged as a transformative tool in this domain, enabling researchers to create precisely controlled, immersive environments for studying rodent navigation behavior [27]. VR systems offer unique advantages for spatial navigation research by allowing exquisite control over sensory cues, precise monitoring of behavioral outputs, and the ability to create experimental paradigms that would be difficult or impossible to implement in physical environments [2]. The integration of VR with advanced neural recording techniques has further accelerated our understanding of the neurobiological basis of navigation, particularly through the study of place cells, grid cells, and head-direction cells [28].

This article presents a comprehensive overview of core behavioral paradigms adapted for VR-based rodent research, with a specific focus on spatial navigation mazes, fear conditioning tasks, and sensory integration approaches. These paradigms have been extensively validated in both real-world and virtual settings and continue to provide powerful frameworks for investigating the neural circuits underlying spatial cognition, learning, and memory [10]. The protocols and application notes detailed herein are designed specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to advance our understanding of navigation behavior and its disruption in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Core Spatial Navigation Maze Paradigms

Spatial navigation mazes constitute fundamental tools for assessing cognitive processes in rodent models. These paradigms have been successfully adapted for VR environments while maintaining their core analytical power and ecological validity.

Virtual Morris Water Maze

The Morris Water Maze (MWM), traditionally conducted in a pool of opaque water, has been translated into virtual environments for both rodents and humans [28]. In this paradigm, animals must learn to locate a hidden escape platform using distal spatial cues.

Table 1: Virtual Morris Water Maze Parameters and Measurements

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Description | Typical Values | Cognitive Process Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task Parameters | Arena shape | Geometry of virtual environment | Circular, rectangular, square [28] | Environmental representation |

| Platform size | Target area for escape | 15% of arena size [28] | Spatial precision | |

| Cue types | Visual landmarks for navigation | Geometric shapes, lights [28] | Cue utilization | |

| Performance Metrics | Escape latency | Time to find platform | Decreases with training [28] | Spatial learning |

| Path length | Distance traveled to platform | Shorter paths indicate learning [28] | Navigation efficiency | |

| Time in target quadrant | Preference for platform area | Increases with learning [28] | Spatial memory | |

| Heading error | Angular deviation from optimal path | Lower values indicate better precision [28] | Navigational accuracy |

The Virtual Water Maze task depends on an intact hippocampus and is therefore a sensitive behavioral measure for pharmacological and genetic models of diseases that impact this structure, such as Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia [28]. The NavWell platform provides a freely available, standardized implementation of this paradigm for rodent research, offering both research and educational versions with pre-designed environments and protocols [28].

Radial Arm Maze in Virtual Reality

The Radial Arm Maze (RAM), developed by Olton and Samuelson, has been adapted for virtual environments to study spatial working and reference memory [29]. This paradigm typically consists of a central arena with multiple radiating arms, some of which contain rewards.

Table 2: Radial Arm Maze Configurations and Performance Metrics

| Maze Characteristic | Options/Variables | Measurement Type | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Number of arms | Structural parameter | 4, 8, or 12 arms [29] |

| Arm length | Structural parameter | Variable based on experimental needs | |

| Paradigm type | Experimental design | Free-choice or forced-choice [29] | |

| Performance Metrics | Working memory errors | Quantitative performance | Revisiting already-entered arms [29] |

| Reference memory errors | Quantitative performance | Entering never-baited arms [29] | |

| Time to complete trial | Temporal performance | Efficiency of spatial strategy | |

| Chunking strategies | Behavioral pattern | Sequential vs. spatial arm entries |

The RAM offers significant advantages for spatial memory research, including the ability to distinguish between different memory systems (working vs. reference memory) and the constrained choice structure that facilitates analysis of navigational strategies [29]. Compared to the MWM, the RAM provides more structured trial parameters and clearer distinction between memory types.

Linear Track and Adaptable Maze Systems

Linear track paradigms provide simplified environments for studying basic navigation and spatial sequencing behavior. Recent technological advances have led to the development of more flexible maze systems such as the Adapt-A-Maze, which uses modular components to create customizable environments [10].

The Adapt-A-Maze system employs standardized anodized aluminum track pieces (3" wide with 7/8" walls) that can be configured into various shapes and layouts [10]. This system includes integrated reward wells with lick detection and automated movable barriers, allowing for complex behavioral paradigms and high-throughput testing. The modular nature of such systems enables researchers to rapidly switch between different maze configurations while maintaining consistent spatial relationships and reward contingencies [10].

Fear Conditioning Paradigms in Virtual Reality

Pavlovian fear conditioning represents another cornerstone of behavioral neuroscience, providing insights into emotional learning and memory processes. Virtual reality adaptations of fear conditioning paradigms offer enhanced control over contextual variables and more ethologically relevant fear stimuli.

Virtual Fear Conditioning Protocol

The PanicRoom paradigm exemplifies a VR-based fear conditioning approach that uses immersive virtual environments to study acquisition and extinction of fear responses [30] [31]. This protocol employs a virtual monster screaming at 100 dB as an unconditioned stimulus, paired with specific contextual cues.

Figure 1: Virtual Fear Conditioning Workflow. This diagram illustrates the three-phase structure of a typical VR fear conditioning paradigm, showing the relationship between conditioned stimuli and measured outcomes.

The fear conditioning protocol typically includes three distinct phases administered in sequence. During habituation, subjects are exposed to the virtual environment and stimuli without any aversive reinforcement. The acquisition phase follows, where specific conditioned stimuli become paired with the aversive unconditioned stimulus. Finally, the extinction phase involves presentation of the conditioned stimuli without the unconditioned stimulus to measure reduction of fear responses [30].

Fear Conditioning Measurements and Analysis

Virtual fear conditioning paradigms employ multiple measurement modalities to quantify fear learning and expression, including both physiological and behavioral indicators.

Table 3: Fear Conditioning Parameters and Outcome Measures

| Parameter Type | Specific Element | Description | Typical Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Parameters | Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | Aversive stimulus | Virtual monster, 100 dB scream [30] |

| Conditioned Stimulus (CS+) | Threat-paired cue | Blue door [30] | |

| Control Stimulus (CS-) | Safety cue | Red door [30] | |

| Inter-trial interval | Time between stimuli | 3 seconds [30] | |

| Measurement Type | Physiological measure | Skin conductance response (SCR) | Electrodermal activity [30] |

| Behavioral measure | Fear stimulus rating (FSR) | 10-point Likert scale [30] | |

| Performance metric | Discrimination learning | CS+ vs CS- response difference |

Research using the PanicRoom paradigm has demonstrated significantly higher skin conductance responses and fear ratings for the CS+ compared to CS- during the acquisition phase, confirming successful fear learning [30]. These responses diminish during extinction training, providing a measure of fear inhibition learning. The robust discrimination between threat and safety signals makes this paradigm particularly valuable for studying anxiety disorders and their treatment [30].

Sensory Integration in Navigation Tasks

Spatial navigation inherently requires integration of multiple sensory modalities, including visual, vestibular, and self-motion cues. Virtual reality enables precise manipulation of these sensory inputs to study their relative contributions to navigation.

Visual Cue Integration in Rodent Navigation

Visual landmarks play a critical role in spatial navigation, providing allocentric references for orientation and goal localization. Virtual environments allow researchers to systematically control the availability and salience of visual cues to determine their necessity and sufficiency for spatial learning.

Figure 2: Sensory Integration in Spatial Navigation. This diagram illustrates how multiple sensory streams converge to form spatial representations that guide navigation behavior.

Studies using VR environments with controlled visual cues have demonstrated that mice can learn to navigate to specific locations using only visual landmark information [2]. In these experiments, mice exposed to VR environments with vivid visual cues showed significant improvements in navigation performance over training sessions, while mice in bland environments or without visual feedback failed to show similar improvements [2]. These findings indicate that visual cues alone can be sufficient to guide spatial learning in virtual environments, even in the absence of concordant vestibular and self-motion cues.

Contrast Features in Rodent Visual Processing

Rodent visual processing relies heavily on contrast features rather than fine-grained shape details, reflecting their relatively low visual acuity compared to primates [32]. This has important implications for designing effective visual cues in VR navigation tasks.

Research on face categorization in rats has demonstrated that contrast features significantly influence visual discrimination performance [32]. In these studies, rats' generalization performance across different stimulus conditions was modulated by the presence and strength of specific contrast features, with accuracy patterns following predictions based on contrast feature models [32]. These findings suggest that effective visual cues for rodent navigation tasks should incorporate high-contrast elements with distinct luminance relationships rather than relying on fine details or complex shapes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of VR-based navigation research requires specific materials and technical solutions. The following table summarizes essential components for establishing these behavioral paradigms.

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Technical Solutions

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Platforms | NavWell | Virtual water maze testing | Free downloadable software for spatial navigation experiments [28] |

| Adapt-A-Maze | Modular physical maze system | Open-source, automated maze with configurable layouts [10] | |

| PanicRoom | Fear conditioning paradigm | VR-based Pavlovian fear conditioning [30] | |

| Hardware Components | Spherical treadmill | Head-fixed navigation | Allows locomotion while maintaining head position [2] |

| Reward wells with lick detection | Automated reward delivery | Liquid reward delivery with response detection [10] | |

| Oculus Rift | VR display | Head-mounted display with 90Hz refresh rate [30] | |

| Measurement Tools | Skin conductance response | Physiological fear measure | Electrodermal activity monitoring [30] |

| Fear stimulus ratings | Subjective fear measure | 10-point Likert scale [30] | |

| Infrared beam break | Lick detection | Precise measurement of reward well visits [10] |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing core behavioral paradigms in rodent navigation research, with specific guidance on experimental design, data collection, and analysis.

Virtual Morris Water Maze Protocol

The following protocol outlines standardized procedures for conducting Virtual Morris Water Maze experiments with rodents:

Apparatus Setup: Configure virtual environment using software such as NavWell, selecting appropriate arena size (small, medium, large) and shape (circular recommended for standard MWM). Place hidden platform in predetermined location, covering approximately 15% of total arena area [28].

Visual Cue Arrangement: Position distinct visual cues around the perimeter of the virtual environment. These may include geometric shapes, lights, or other high-contrast visual elements that can serve as distal landmarks [28] [32].

Habituation Training: Allow animals to explore the virtual environment without the platform present for 5-10 minutes to reduce neophobia and familiarize them with the navigation interface.

Acquisition Training: Conduct multiple training trials per day (typically 4-8) across consecutive days. Each trial begins with the animal placed at a randomized start location facing the perimeter. The trial continues until the animal locates the platform or until a maximum time limit (typically 60-120 seconds) elapses. After finding the platform, allow the animal to remain on it for 15-30 seconds to reinforce the spatial association.

Probe Testing: After acquisition training, conduct probe trials with the platform removed to assess spatial memory. Measure time spent in the target quadrant, number of platform location crossings, and search strategy.

Data Collection: Record escape latency, path length, swimming speed, time in target quadrant, and heading error. Analyze learning curves across training sessions and compare performance between experimental groups.

This protocol allows assessment of spatial learning and memory, with impaired performance indicating potential hippocampal dysfunction or cognitive deficits [28].

Virtual Fear Conditioning Protocol

The following protocol details implementation of VR-based fear conditioning using the PanicRoom paradigm:

Apparatus Setup: Configure virtual environment with two distinct doors (CS+ and CS-) using contrasting colors (e.g., blue and red). Program the unconditioned stimulus to appear when the CS+ door opens [30].

Habituation Phase: Expose subjects to the virtual environment with both CS+ and CS- doors presented multiple times (typically 8 trials total) without any aversive stimulus. Each door presentation should last approximately 12 seconds with 3-second intervals between trials [30].

Acquisition Phase: Present CS+ and CS- doors in random order. When the CS+ door opens, present the unconditioned stimulus immediately. The US should consist of a threatening stimulus such as a virtual monster accompanied by a 100 dB scream. The CS- door should never be paired with the aversive stimulus.

Extinction Phase: Present both CS+ and CS- doors without the unconditioned stimulus to measure reduction of conditioned fear responses.

Data Collection: Throughout all phases, record skin conductance response and subjective fear ratings. Calculate discrimination scores between responses to CS+ and CS- to quantify fear learning.

This protocol typically reveals significantly higher SCR and FSR to CS+ compared to CS- during acquisition, with these differences diminishing during extinction [30]. This paradigm provides a powerful tool for studying fear learning and its neural mechanisms.